|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

SETTLEMENT AND AGRICULTURE

Introduction

Since the flow of miners through the area in the 1860s, the location and growth of communities in northwestern Montana have depended on the location of the railroad and other transportation routes, the topography, the development of markets, and government land policies. The most significant influence on the settlement of the Flathead Valley was the coming of the Great Northern Railway to the valley in 1891. The Forest Homestead Act of 1906 encouraged settlement of agricultural land within national forests. These "forest homesteads" are discussed in a separate chapter.

Settlement Up to 1871

The original inhabitants of northwestern Montana were, of course, Native Americans. One of the centers of Kootenai activity was the Tobacco Plains along the Kootenai River. Prior to 1850 the Kootenai hunted seasonally at Flathead Lake, competing with the Pend d'Oreilles, but after that time they lived there permanently, replacing or intermixing with the original population (Malouf 1952:2). The fur trade brought to the Native Americans of northwestern Montana an influx of trade goods along with the replacement of the aboriginal economy with new materials, the hunting and trapping of game for material gain over long-term subsistence, and disease, oppressive government policies, and restrictions of their movements.

The only way to earn a living in the early 1850s was by hunting, trapping, or trading, or by working for someone else who hunted, trapped, or traded. In those years many people of French-Canadian, Scottish, and Iroquois heritage lived in western Montana, a legacy from the fur trade (Weisel 1955:xxiv, 48).

The Hellgate Treaty of 1855 established the Flathead Indian Reservation in the lower Flathead Valley for the Flathead (or Salish), Pend d'Oreille (or Kalispel), and Kootenai tribes. Most of the bands of these tribes slowly moved onto the Reservation. The creation of the Reservation opened the door to permanent non-Native American settlement of the valleys of western Montana. In 1887 the Dawes Act divided the rich bottomlands of the Reservation into individual allotments, and the land considered surplus was given to Euroamerican settlers (Historical Research Associates 1977:6-7).

John Owen established Fort Owen in the Bitterroot in 1850, and for a few years he traded with Native Americans, people of mixed descent, and the few Euroamericans in the area, all of whom paid mostly in livestock, furs, or labor. According to Owen's ledger and other sources, in 1851 the only Euroamericans in western Montana were a few Jesuits, HBC men, and about 15 others, including two mountain men. In 1860 Owen faced his first trading competition, when Frank Worden and Christopher Higgins built a trading post at Hellgate on the Mullan Road. From then on, Fort Owen was no longer the center of trade in the area (Weisel 1955:xxiii, xxx).

In 1858, the resident non-Native American population of Missoula County (all of northwestern Montana at that time) was approximately 200 people. Because the Oregon trail lay 200 miles south of western Montana, most emigrants never saw the region. The early settlement of western Montana was overshadowed by placer gold mining beginning in the early 1860s. The Mullan Road, built from 1859-62 between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, enabled the mining development of western Montana. During the 1860s, western Montana was not self-sufficient. Local flour and lumber and some agricultural products were available in the Missoula area, but all manufactured items had to be brought in. In 1870 the population of Missoula County was just over 2,500, but by 1880 it had hardly changed (these figures do not include the gold miners passing through the area) (Coon 1926:49-50, 53, 56-57, 68, 71).

The W. W. DeLacy map published in 1870 showed a "half-breed" settlement located north of Flathead Lake, where a Native American trail crossed Ashley Creek. The small settlement had been established several decades earlier. In 1845 two French Canadians joined the Kootenai living at the north end of the lake and built a cabin on Ashley Creek, spending most of a year there. Two years later, four more French Canadians arrived, including Louis Brun, a Quebequois, and his Kalispel wife Emily. When gold was discovered in California, they and other families, including a man named Benetsee Finley, left for the gold fields. Most of them returned to the Ashley Creek area in 1850, but the Bruns moved to the Jocko area and then Frenchtown. Men who came and returned to the Flathead in 1850 may have included Joe Ashley and Francois Grevelle, both of whom are mentioned often in histories of the early settlement of the Flathead Valley. When Lt. John Mullan passed through the upper Flathead Valley in 1854, he reported that "Our camping ground — was represented — by the Indians as a great resort of their tribe and the half-breeds of the country some years ago" (Holterman 1985:25; Shea 1977:37-38, 41; T. White 1964:27).

Joe Ashley, for whom Ashley Creek is named, had come to the Flathead in the mid-1840s. He and Angus McDonald (an HBC trader), Peter Irvine (a Shetlander), Francois Finley, and Laughlin McLaurin and several others farmed in a small way at the head of the lake. McLaurin (also spelled McLaughlin, McLaren, or McGauvin) was among the first traders at a post near the head of Flathead Lake. Ashley succeeded McLaughlin as trader, under the supervision of Angus McDonald of Fort Connah. In the late 1860s several of the families living at Ashley Creek left the area because of Blackfeet raiding, some only temporarily. Ashley stayed on, later moving to the foot of Flathead Lake and then selling out in the 1880s and leaving the area (Shea 1977:39-40; McCurdy 1976:71-72; Johns 1943 1:35).

There are reports of a few Euroamericans coming through the Flathead Valley in the 1860s besides those who settled at the head of the lake and those heading to the mines in southeastern British Columbia. Some traveled into Montana from the north. Carpenter Esna D. Dashiell arrived at Flathead Lake in August of 1864. Frank Normandie came to Montana from the Fraser River in Canada and continued on to the Deer Lodge Valley via Flathead Lake in 1862 (Johns 1943 IX: 149).

1871-1891

Until the Great Northern Railway entered the Flathead Valley in 1891, development of the area was slow and uncertain. Supplies came to the Flathead by pack train from Walla Walla, The Dalles, or the Missoula area. The first post office was established at Scribner (or Flat Head Lake), near Flathead Lake, in 1872, but it was only open until 1875 (Robbin 1985:15, 65).

In the 1870s several Euroamericans visited the upper Flathead Valley, some remaining a considerable time. In the winter of 1871-72 a number of men from the Missoula area, including Harry Burney, A. B. Hammond, and others wintered on the meadow subsequently filed on by Burney. Although most of them left the following spring, Burney stayed and raised cattle and horses. He was the only Euroamerican man living on the east side of the Flathead River until 1883, when several families located on that side. Burney was originally from Ireland and had participated in gold rushes in California and then in British Columbia. He recalled that a number of Flathead settlers left in the late 1870s when it was reported that Sioux leader Sitting Bull was returning from Canada via the Flathead (Lang 1923:1-3; Isch 1950:19; Johns 1943:III, 35; Ingalls ca. 1945:1).

In the late 1870s a few men entered the upper Flathead in order to push the cattle range north of the reservation. These included former placer miners Nick Moon and Thomas Lynch. Moon later became the first in the valley to raise vegetables and to use irrigation for farming (see Figure 10). The lack of transportation continued to be a problem, however, and according to the 1880 population census there were only 27 Euroamericans living at the head of Flathead Lake. All were livestock men except for one woman, two girls, and a blacksmith (Isch 1950: 19; O'Neil 1990:12; Ingalls ca. 1945:1-2; Biggar 1950:86-87; Johns 1943:VI, 66).

|

| Figure 10. Nick Moon, ca. 1895 (Great Northern Railway Country 1895). |

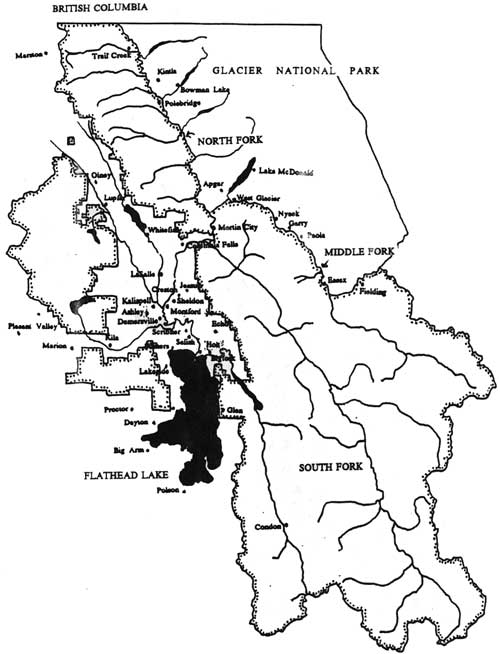

The next limited wave of settlement began in 1880, when John Dooley came to the Flathead. In 1881 he opened a small trading post called Selish on the Flathead River. For a number of years the Selish post office served people from Marias Pass on the east to the Idaho boundary on the west and the Canadian line on the north. In 1884 the post office at Ashley was established (the town of Ashley was later absorbed by the newer town of Kalispell). Mail was carried on horseback from the south along the west side of Flathead Lake. Daily mail for the upper Flathead was not established until steamboating on Flathead Lake became regular (see Figures 11 and 12) (Isch 1950:20; Johns 1943:IX, 14-15; Elwood 1980:7).

| Town | Dates of Post Office | First Postmaster | Comments |

| Apgar | 1913-30, 1942-44 | Jessie Apgar | |

| Ashley | 1884-91 | Andrew Swaney | |

| Big Arm | 1911- | Marion F. Lamb | |

| Bigfork | 1901- | Everit Sliter | |

| Blodgett | 1903-04 | Daniel Whitaker | |

| Bowman Lake | 1924-26 | Fred Gignilliat | associated with Skyland Boys Camp |

| Cabinet | 1901-05 | Angus Hutton | |

| Columbia Falls | 1891- | James Kennedy | formerly known as Monaco |

| Condon | 1952- | Russell Conkling | |

| Creston | 1894-1956 | Charles Buck | |

| Dayton | 1893- | Clarence Proctor | |

| Demersville | 1889-1892, 1893-1898 | John Clifford | formerly Clifford |

| Echo | 1901-05 | William Kelsey | |

| Essex | 1898- | William Glazier | railroad station named Walton |

| Fielding | 1909-14, 1915-19 | Joseph Cremans | |

| Flat Head Lake | 1872-1875 | valentine Coombes | originally Scribner |

| Garry | 1923 | James Beardsley | |

| Glen | 1890-1903, 1910-14 | William Bohannon | |

| Harrisburg | 1903-05 | Claude Bradley | replaced by Fortine post office |

| Holt | 1890-1908, 1912-15 | Euegene Soars | |

| Jessup | 1909-18 | Herbert Jessup | |

| Kalispell | 1891- | Charles Harrigan | |

| Kila | 1901- | Harry Neffner | |

| Kintla | 1916-25 | Mary Schoenberger | |

| Lake McDonald | 1905-55, 1946-66 | George Snyder | head of Lake McDonald |

| Lakeside | 1948- | John Stover | formerly Chautauqua |

| LaSalle | 1900-05 | Walter Jellison | |

| Leona | 1896-1899 | Frank Strycker | |

| Lupfer | 1917, 1924-25, 1930-34 | Hubert Herman | |

| Marion | 1892-1894, 1904-06, 1930-34 | Charles Mitchell | also called Swan |

| Marston | 1895-1907 | Cyrus Marston | |

| Martin City | 1947- | Clara Frederick | |

| Mock | 1921-39 | Peter B. Wiggen | |

| Montford | 1900-10 | Arthur Lindsey | |

| Murray | 1900 | Isaac Murray | |

| Nyack | 1912-42 | George Robertson | railroad station called Red Eagle |

| Olney | 1907-08, 1914-17, 1918- | Elizabeth Dickerhoof | |

| Paola | 1914-19, 1920-28 | Marie Cameron | |

| Pleasant Valley | 1892-1895, 1901-05 | George Allen | formerly Richland and Meadow |

| Polebridge | 1920- | Benjamin Hansen | |

| Polson | 1898- | Henry Therriault | |

| Proctor | 1910- | Clarence Proctor | |

| Rollins | 1904- | Rehenault Rollins | |

| Selish | 1881-1891 | John Dooley | |

| Sheldon | 1887-1903 | Sarah Sheldon | |

| Somers | 1901- | John Sawyer | |

| Trail Creek | 1921-54 | Benjamin Price | |

| Trego | 1911-19 | Charles Miller | |

| West Glacier | 1900- | Edward Dow | formerly Belton |

| Whitefish | 1903- | John Skyles |

| Figure 11. Post offices in the Flathead Valley area. Towns in bold type still have post offices; the rest do not (Cheney 1983: passim). |

|

| Figure 12. Locations of most of the towns that have had post offices in the Flathead Valley area. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Although some settlers were moving in, the relatively few residents of the Flathead in the early 1880s were mostly quartz miners from Butte and other areas, a few trappers, some buffalo hunters, and a number of French Canadians. According to Frank Linderman, "Without the least knowlege of farming these men, many of them confirmed bachelors, took up claims and became farmers as though they had reached the realization of a lifelong dream." Many family men found it necessary to leave their wives and children behind in the Flathead to prove up on their 160-acre homestead claims while the men worked in the mines in Butte, lumber mills, and so on. Others would live on their claims for the shortest time required and then make cash entry proof and return to their jobs (Linderman 1968:45; Mauritson 1954; Duncan ca. 1923:5).

The early stockmen tried to discourage farming in the upper Flathead, telling newcomers tales of early frosts, low rainfall, and vicious mosquitos. Until the late 1880s, in fact, very few agricultural products were raised in the area; most were brought in from Missoula. Since the early market for produce was local only, many farmers also spent much of their time logging (Mauritson 1954; Elwood 1980:6).

In the 1880s the Flathead Valley was largely wooded. Scattered through the dense forest were natural prairies, occasional groves of ponderosa pine, and small lakes. The first area settled was the high ground to the north and northwest of Kalispell because it was dry and not heavily timbered; some of the areas that are now good farmland, such as the Creston area, were too wet and swampy to till in the early years (Murphy 1983:142).

After the Northern Pacific Railroad reached Missoula in 1883, more and more people began coming to the upper Flathead Valley, some of them railroad construction workers looking for a place to settle. By 1890 the upper Flathead Valley reportedly had 3,000 occupants. Walkup and Swaney established a trading post on Ashley Creek along the Fort Steele-Kalispell Trail in 1883. At that time, the round trip from the post to Missoula took about three weeks. In the early years of settlement of the Flathead Valley, various bands of Native Americans camped in the valley tanning hides and selling moccasins and other products to settlers. According to a woman who lived in the Flathead in 1883, "except for the nomadic Indians, life for the most part, centered around the trading posts, a few ranches, and an occasional trapper's cabin" (Isch 1950:20-21; Patterson n.d.: Ch. 15, p. 2; Beck 1981).

Relations between the Native Americans and the incoming settlers were generally peaceful in the Flathead Valley. Two Kootenai were lynched in Demersville in 1887, however, and three prospectors were killed on Wolf Creek by Native Americans that same year. African-American soldiers from Fort Missoula were sent to the Flathead in 1890 as peacekeepers for several months, but they were not really needed and spent most of their time clearing trails and roads (Isch 1948:72; Elwood 1980:10-11).

In 1885, when the first school census was taken in the area, only 95 children lived west of the Flathead River, north of the Flathead Indian Reservation, and south of the Canadian boundary. Three years later, according to Flathead Valley old-timer George Stannard, there were about 100 families living on valley ranches (Johns 1943:III, 115; Vaught Papers 1/IJ).

T. J. Demers founded the town of Demersville in 1887, located at the head of navigation on the Flathead River. For a few years, until the rise of Kalispell in the early 1890s, Demersville was the largest town in the upper Flathead. The first newspaper in northwestern Montana, the Inter Lake, began publishing there in 1889. Settlers flowed in and out of Demersville, most of them trying to reap profits from the Flathead's abundant resources or from each other (McKay 1993).

Montana Territory, established in 1864, became a state in 1889, primarily because of concern over the lack of local political control. By this time, settlement of the upper Flathead had begun in earnest. A few early settlers of the upper Flathead Valley even decided that settlement was getting "too thick." For example, George Hall, a prospector, hunter and trapper, left the Flathead in 1889 to move to Alaska (Vaught Papers 1/K).

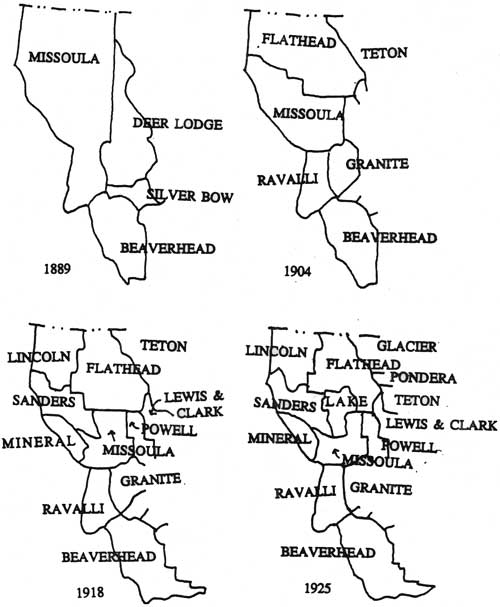

Flathead County was created out of Missoula County in 1893 because of the long distance to Missoula. The county originally had about 8,500 square miles, but subsequent additions and losses (due to the formation of other counties) reduced its size substantially (see Figure 13). Kalispell became the county seat in 1894.

|

| Figure 13. Counties in western Montana: 1889, 1904, 1918, 1925 (from Cheney 1983). (click on image for a PDF version) |

1891 to World War II

When the Great Northern Railway was deciding where to lay its route through the valley, Demersville boasted of its navigable waters, Ashley that it was at the valley's natural outlet to the west, and Columbia Falls that it was where the tracks had to emerge from Bad Rock Canyon (Elwood 1980:30). But the GNRR chose none of these existing towns as its headquarters; instead, the new town of Kalispell became the division point.

When the railroad was known to be coming through the Flathead, old prospectors and ranchers came in to homestead the land. They were speculators on a small scale; they obtained title until other settlers came to purchase their land. Soon after the railroad arrived, experienced farmers followed ("Kalispell and the Famous Flathead" 1894:6). For several decades the GNRR operated an extensive advertising campaign to attract settlement to towns along its railroad line, including towns and agricultural areas in western Montana.

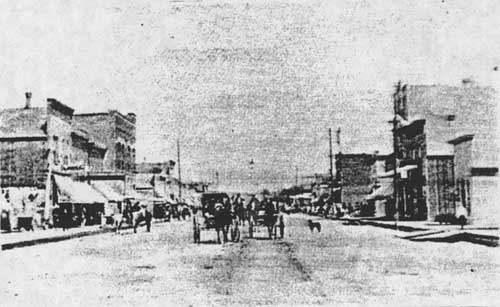

Several existing towns in the Flathead were founded directly because of the railroad coming through the valley. One of these was Columbia Falls, which was platted by a group of Butte business men as a speculative venture. Kalispell was established in 1891, soon replacing Demersville four miles to the southeast, to serve as the division point for the railroad (see Figure 14). In 1904 the main line of the Great Northern was moved to the north end of the valley, and the town of Whitefish was platted and carved out of the woods to serve as the new division point (the previous settlement in the area had been located at the foot of Whitefish Lake). Whitefish grew rapidly, and by spring of 1905 it boasted 950 residents, many of them railroad workers (Macomber 1976:3; Schafer 1973:2, 6, 27). The town of Essex (formerly called Walton) was established as a railroad town, and it too housed many railroad workers (the helper engines that bring trains over Marias Pass have always been based out of Essex).

|

| Figure 14. Street scene in Kalispell, ca. 1895 (Great Northern Railway Country 1895). |

The Japanese who worked for the railroad were hired and cared for by an employment agency called the Oriental Trading Company, which opened a Kalispell branch in 1899. Two years later the company had about 750 men working on the Kalispell division (McKay 1993:18).

The NPRR hired 15,000 Chinese to help construct its line through Washington, Idaho, and Montana in the early 1880s, but very few if any Chinese appear to have worked on the GNRR. Instead, Chinese in the Flathead Valley provided a variety of goods and services, owning or working in laundries, restaurants, and stores and working as servants, cooks, and gardeners. In the mid-1880s an anti-Chinese movement throughout the West caused many to flee to urban centers. The first Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882, prohibiting Chinese labor immigration. A 1902 act banned all Chinese from entering the United States for temporary settlement purposes. In 1895 Kalispell labor organizations launched a boycott against businesses employing or buying from Chinese. Both Chinese men and opium (after it became illegal) were smuggled across the border from Canada at Gateway and along the North Fork of the Flathead in the 1890s and following years. The Chinese community in Kalispell, as elsewhere, eventually disappeared because of laws prohibiting immigration and because the group was overwhelmingly male (McKay 1993:20-21; Elwood 1980:61).

Between 1910 and 1934 more than 61,000 acres of the Flathead Indian Reservation passed out of Native American ownership. Some Euroamericans bought summer home sites on Flathead Lake, but more commonly they registered for land in 1909 and selected homesteads when the Reservation was opened for settlement (Bergman 1962:85-89; Biggar 1950:131, 134, 137-138).

The first cash crops grown in the upper Flathead were oats (largely for home feed), wheat, and potatoes. The financial panic of 1893 led to very low agricultural prices for a time, but soon prices and demand rose. There was such a demand for labor that a delegate was sent East to induce laborers to come to the Flathead, and reportedly several thousand did come to the Flathead to live and work. In 1897 a number left for the Klondike gold rush, but that same gold rush created a demand for food and other products that aided the Flathead. Similarly, the Spanish-American War of 1898 slowed the general economy some, but the war demand for horses and supplies helped the local economy (Mauritson 1954).

In the early 1900s in the Flathead, farmers were raising spring and winter wheat, oats, rye, timothy hay, clovers, vegetables, dairy cattle, and various fruits. The population of the Flathead boomed in the 1910s because of high agricultural prices and high yields. The agricultural drought started in the spring of 1917, and 1918 was "unrelievedly grim" in Montana. The Flathead was not seriously affected by the drought until 1919, however (Read 1904:49-50; Toole 1972:71-72).

Apple orchards and other fruits were being raised along Flathead Lake by the 1890s. The first commercial cherry orchard on the east shore of Flathead Lake was planted in 1930, and a cherry growers' cooperative was organized in 1935 (the year of a freeze that killed many trees) (Robbin 1985:, 73-74, 77).

In the 1930s farm families from drought-stricken eastern Montana moved to the Flathead, but many of these settled on unsuitable land. By the spring of 1939 there were 1,150 farm families in Flathead County who were classified as migratory or stranded, living on submarginal or cut over lands and unable to earn a living. Flathead County had far more destitute farmers at that time than any other county in Montana. After peaking in 1938, the county's population declined in the early 1940s. Flathead County furnished more men per capita to the armed services in World War II than any other county in the United States (Sundborg 1945:11).

Tractors were first used in the Flathead in 1905, but they were not widely employed until World War I and later. The mechanization of logging in the 1930s led to the end of the market for horses and horse feed. Extension work started in the county in 1914, and the Northwestern Montana Branch Experiment station was established in Creston in 1946 (Mauritson 1954).

In 1940, less than 3% of the agricultural land in the county was irrigated. In 1945, the principal crops of Flathead County farms were field crops, livestock, and dairy products (Sundborg 1945:39, 48). Peppermint oil, now an important Flathead agricultural crop, had not yet been tried in the Flathead Valley.

The more inaccessible valleys of the Flathead were not settled as early as the main valley. The Middle Fork, for example, had only a few squatters in 1899, but in 1923 a school was built in Nyack to accommodate settlers' children. Essex had a number of residents early on because of the railroad work there, but the other railroad stations were section houses only. Coram (also known as Citadel) was not founded until 1905, when it was established as a logging town. By the late 1890s there were a few prospectors' cabins in the South Fork (one, belonging to "Batti," was probably that of Baptiste Joyal) (Sztaray 1994:14; Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:55, 68; newspaper article in FNF CR).

Bigfork was platted in the early 1900s by Everit Sliter, who had a large orchard there. The hydroelectric plant in Bigfork was built in 1901 to serve the valley. In the early 1900s there was great excitement about a pulp mill that was believed to be coming to Bigfork but never materialized. Near Bigfork was a ferry on the Flathead River, Holt Ferry, that was not replaced by a bridge until 1942 (Robbin 1985:59; Elwood 1980:198; Flint 1957:7).

Kila was originally a station stop on the Great Northern known as Sedan. The town was platted in 1914 and was named for William Kiley, a partner in the Enterprise Lumber Company mill located there (Elwood 1980:209).

The upper Swan Lake area was first settled in the early 1890s by people living around Goat and Lion Creeks. In 1899 there were only about 10 houses (all unoccupied) between the head of Swan Lake and Holland ranch at the mouth of Holland Creek. Ben Holland sold his ranch to the Gordons in 1905 (he had earlier named Gordon Pass for his friend Dr. Gordon). There was also a trapper's cabin at the foot of Elbow (Lindbergh) Lake at that time (Flint 1957:30; Ayres 1900 "Lewis & Clarke":55; Wolff 1980:53).

One of the most colorful, if short-lived, towns in the area was McCarthysville, located on a tract of level ground between Summit (Marias Pass) and Essex (see Figure 15). The town was founded by a timber cruiser, Eugene McCarthy, while he was inventorying the timber resources along the proposed railroad right-of-way through the area in 1890. The town was located on one side of Bear Creek and the railroad construction camp on the other side (the latter housed up to 4,000 workers). The resident population of McCarthysville peaked at about 1,000 people, and during this period one passer-through labeled it a "seething Sodom of Wickedness." The construction camp was moved when the railroad reached the Flathead Valley in 1891, and the headquarters was relocated to Kalispell, Most of McCarthysville was destroyed by fire in 1921 (Murphy 1993; Hidy 1988:81; Atkinson 1985:16).

|

| Figure 15. The town of McCarthysville, located along the Great Northern Railway line near Bear Creek, ca. 1918 (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

World War II to Present

The establishment of new communities in the Flathead Valley after World War II was directly linked to the building of the Hungry Horse Dam, completed in 1953. The towns of Martin City and Hungry Horse were created because of the dam project, and all the settlements in and near the Canyon grew (and declined) accordingly. Columbia Falls' population continued to grow in the 1950s due to the construction and opening of the Anaconda Aluminum Company plant.

Populations of Selected Towns, 1940-1960

| 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | |

| Coram | 200 | 500 | 300 |

| Martin City | 0 | 1,000 | 300 |

| Hungry Horse | 0 | 1,335 | 300 |

| Columbia Falls | 637 | 1,232 | 2,500 |

| Kalispell | 8,245 | 9,737 | 10,151 |

(FNF "Timber Management, Coram" 1961:42)

The construction of the Hungry Horse Dam between 1948 and 1952 gave work to as many as 2,550 men. Legislation offering industries located within 15 miles of the dam a lower electricity rate was a key factor in the ACM decision to build the aluminum plant in Columbia Falls. The first production of aluminum at the plant was in 1955, when it employed over 600 men. Following a period of unusually high economic activity in the valley because of Hungry Horse Dam, the construction and operation of the aluminum plant maintained or increased the activity in the valley (M. C. Johnson 1960:2-3; Ruder 1967:2).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap4.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |