|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

MINING

Introduction

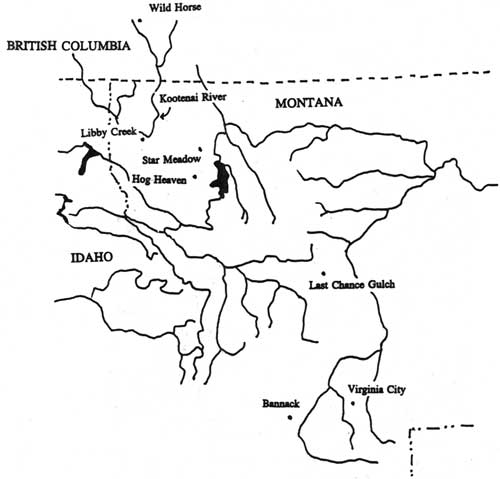

The Flathead Valley has never experienced a major mining boom. In the early years, the area was most closely connected to the rush to the diggings at Wild Horse Creek in British Columbia in 1864 (see Figure 7). The development of mining districts in the Flathead was hampered by transportation and marketing challenges. The only mining district to ship significant quantities of ore was Hog Heaven, which operated in the late 1920s through 1946.

|

| Figure 7. Historic mining districts in northwestern Montana and vicinity. |

During the 1930s there was a resurgence of interest in mining among unemployed people looking for ways to supplement their incomes. Local men and women prospected in the mountains of the Flathead National Forest, but as in earlier decades they generally had little success. Only one mining claim on the Flathead National Forest has been patented (the Baptiste claim with copper values near Baptiste Mountain). Other claims have been staked, but the land is still within the national forest system.

Evidence of mining activity on the Forest is not as rich as it is in other parts of Montana, generally because the Flathead did not experience an extensive mining boom. Prospectors' pits and cabins can still be found, however, and remains of mine development in the Hog Heaven and Star Meadow mining districts exist today. Most of the evidence of the coal mining in the North Fork is now gone.

Oil Fields

The founding of Columbia Falls in 1891 and the arrival of the Great Northern Railway in the Flathead Valley that same year led to increased interest in the natural resources, particularly mineral, up the North Fork of the Flathead. In 1892 prospectors filed the first oil claims in Montana, which were located in the Kintla Lake area of the North Fork within what is now Glacier National Park. Although Native Americans and fur trappers had reportedly known of oil seeps in the area for some time, these prospectors were alerted by bear hides sold at Tobacco Plains that smelled of kerosene. In 1892 a local newspaper reported that the North Fork valley had been taken up by settlers hoping to find oil beneath their homesteads and waiting to hear of a railroad coming up the valley. Neither happened. A shortage of capital combined with the financial panic of 1893 and the subsequent depression led to the temporary abandonment of the oil district in the 1890s ("Flathead Coal" 1892:1; DeSanto 1985:26-28; Willis 1901:782; Bick 1986:5).

In 1900 interest in the Kintla oil fields revived. A group of Butte businessmen organized the Butte Oil Company and the next year filed a claim on land near Kintla Lake. This area was practically inaccessible at the time; it was reached from Tobacco Plains via a trail over the Whitefish Divide, along the "coal trail" on the west side of the North Fork, or along the "Canadian trail" on the east side of the river from Belton (now West Glacier). The Butte Oil Company therefore hired men to build a road north from Belton to the Kintla area. Workers completed a rough 8'-wide wagon road in 1901, and drilling machinery from Pennsylvania was hauled up to Kintla Lake along the road. Drilling began in 1901, other oil companies formed, and the Kintla oil boom was on (see Figure 8) (DeSanto 1985:28, 30, 31; J. B. Collins to John O. Bender, 10 August 1901, entry 13, box 5, RG 95, NA). Out-of-state boomers and oil promoters were putting "their ears to the ground listening for the sloshing of oil," and speculators (including local people) filed oil claims in the area (Kalispell Bee, 2 July 1901). In 1901 a magazine writer summed up the excitement over the Kintla oil fields as follows:

perhaps there is no more beautiful region in the whole northwest than this virgin wilderness, which the enterprise of man will soon convert into a populous and busy territory with all of the industries of a great oil field in full blast (quoted in Bick 1986:10).

|

| Figure 8. Kintla oil well, located near mouth of Kintla Creek, 1904 (in today's Glacier National Park) (courtesy of the Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula). |

The first oil well on the shore of Kintla Lake reached a final depth of 1400', but in the winter of 1902-03 almost the whole plant burned. The wells never reached a profitable pocket of oil. In 1912 all claims of the Butte Oil Company were declared void. Another company built a derrick near the North Fork River several miles below Kintla Creek, but it stopped drilling in 1903 due to a lack of capital (DeSanto 1985, 34-36).

Canadians also got involved in oil exploration and drilling in the area. In late 1901 a Canadian company began drilling a few miles from the townsite of Waterton. In 1913 there was another boom of coal and oil exploration in the area as more geological surveys were conducted. A wagon road was built from Corbin over Flathead Pass south to the boundary, and a survey for a railroad line paralleled the road. By 1930 three oil and gas companies were once again active on the Canadian side of the North Fork, and at least three oil derricks were built. Exploration was spasmodic and was abandoned in the late 1930s, however, because the drilling did not define sizeable pockets of oil (Ringstad 1976:5).

Oil was discovered in the Swiftcurrent area on the east side of the Rockies in 1903, and a short-lived boom occurred there. After a few years production declined, however, as the wells were lost to penetrating water. As of 1911, there were over 200 mining claims in newly created Glacier National Park. Most of the valid claims were in the Kintla Lake area on the west side and the Swiftcurrent and Lake Sherburne areas on the east side (Douma 1953:20-21; Buchholtz 1969: 13).

One Flathead Valley resident did do well on oil claims, but the claims were not in the Flathead. Charlie Emmons homesteaded in the Truman Creek area and later worked as a forest ranger for the Blackfeet National Forest. Emmons was a self-made practical geologist. With several other Kalispell residents he raised the money to bring experts from California to examine the Kevin-Sunburst oil and gas field, and then he gathered leases in the area. His company ended up realizing great profits (Kalispell Times, 4 December 1941).

In the late 1940s and early 1950s oil and gas companies pressured the Forest Service for leases in the Bob Marshall Wilderness. No leases were granted because they were seen as incompatible with wilderness preservation. Exploratory oil and gas work has been done on other drainages and on private land in various Flathead drainages (Shaw 1967:74, 121).

Coal Deposits

Another early boom in the North Fork of the Flathead revolved around the coal fields located near Coal Creek. Raphael Pumpelly on his 1883 trip through the northern Rockies identified the coal beds on west side of the North Fork, and local prospectors promoted and developed the beds. The Great Northern Railway (GNRR) needed coal for fuel but found the lignite coal in the North Fork unfit for railroad use. The Anaconda Copper Mining Company (ACM) also investigated, hoping the coal could be converted to coke and used in its smelting operations, but found the coal too low-grade for such use (Sheire 1970:195).

In 1887 seven men located coal claims on the Coal Banks at the urging of Marcus Daly of the ACM. They sold their holdings three years later to James Talbott and others of Columbia Falls' Northern Improvement Company for $50,000. Talbott had a steamboat built to bring out the coal via the North Fork of the Flathead. In early 1892 the Oakes set out on its maiden (and only) voyage; it wrecked in rapids near the mouth of Canyon Creek, short of its destination. The next year Talbott brought out some coal on a raft, but after the second raft also wrecked he gave up on this method (Inter Lake, 5 December 1890; Johns 1943 III:38; Rognlien ca. 1940:1-7).

By 1892 the 102' Emerson tunnel had been drive into the bank, exposing about 30' of coal, and by 1906 several 20-50' tunnels had penetrated a number of outcrops. Eventually the First National Bank of Butte purchased the coal mine. After the county built the road to Coal Creek in the 1910s, Claude Elder leased the holdings. He operated the coal mine until 1942, selling coal as a heating fuel to hotels, hospitals, individuals, and so on in the Flathead Valley. At the start of World War II, when the demand for low-grade coal decreased, war-time labor shortages interfered with production, and the mine was shut down (Rowe 1906:49; "Flathead Coal" 1892:1; Glacier View Ranger District 1981:2, 5; Sundborg 1945:9).

Coal beds were also located in the South Fork drainage. In the summer of 1891 William Curran camped at the coal fields and used the coal for fire and blacksmithing. He and others also found gold- and silver-bearing quartz in the area. In 1892 Frank Linderman drove a tunnel on his coal claim in the South Fork and reported, "Men are going in, in great numbers, some with and some without provisions." The Flathead National Forest's Coal Banks Ranger Station, 35 miles from Coram near the junction of the Echo Lake and the main South Fork trails, occupied land that had been claimed as coal lands since 1898. Beyond sinking a shaft about 10' in depth and relocating each year, however, no significant development work had been done by 1918. The Forest Service reported that the coal was low-grade lignite, lying in a small strata, and that even if a railroad were built, coal mining there would not be profitable ("New Mining Country" 1891; Johns 1943 VII: 115; Flathead National Forest "General Report" 1918).

Prospectors wandered all over the Flathead country in the 1890s. Coal was found on the first creek above Nyack (then known as Coal Creek), and in approximately 1910 the Ralston brothers attempted to a develop a coal mine on the Middle Fork within the area that is now the Bob Marshall Wilderness (Vaught ca. 1943:281; Merriam 1966:21).

On the Canadian side of the international boundary, in the early 1900s a major outcropping located about 12 miles north of the border in the North Fork was mapped, but there was little development. The town of Fernie was founded in 1889 when a company was formed to mine coal in the area. By 1903 six mines had been developed in the Fernie area, and at least one other was still in operation in 1967 (Ringstad 1976:5; Fernie Historical Association 1967:25, 41).

Placer and Lode Mining

General

For almost a decade after the California gold rush started in 1848, mining was carried on extensively only within that state. In the 1860s, however, the industry expanded eastward into the Rockies. Fort Colvile, for years the chief inland post of the HBC, became the first important center for mining development in the Inland Empire. Walla Walla, another important center, was founded in 1856 (Trimble 1914:7, 10-11, 15, 21).

The first gold in the future state of Montana was discovered in the early 1850s, but no rush of miners came into Montana until the strikes at Bannack City (1862), Alder Gulch (1863), and Last Chance Gulch (1864). From these mining towns prospectors ventured out looking for new lodes. Mining dramatically hastened the pace of development in the region. The large population increases led to increased demands for timber, transportation, and goods and services. Placer gold started the early rushes because it was easily recognizable and it could be extracted without large investments of capital.

The first gold stampede that directly affected the upper Flathead Valley was the rush to the Wild Horse diggings in British Columbia in 1864. The previous year two men had brought gold dust and nuggets found in what became known as Finlay Creek to the trader at Fort Kootenai in Tobacco Plains. Prospectors flooded into the area the next year, and a rich mining town sprang up. Most of the miners came from the United States, coming in from Walla Walla and the Idaho panhandle, but some traveled north through Montana. In 1865 there were over 5,000 miners in the area. This rush had the secondary effect of familiarizing some people with the upper Flathead country, and a number returned to the area to prospect after the profits at Wild Horse declined (Isch 1948:64; Graham 1945:126, 131, 132; Ivorson n.d.:42).

There was also some mining activity to the west of the Flathead Valley during this period. By the fall of 1867 over 500 miners were working on Libby Creek (a second rush in that area began in 1885). A placer mining stampede reportedly occured on Grave Creek on the west side of the Whitefish Divide in the early 1860s. The most productive mine in the Whitefish Divide was Independence, which yielded chalcopyrites of copper (a mineral consisting of copper-iron sulfide, an important ore of copper). Twelve men were working the mine in 1894 and shipping the ore by boat to Jennings (M. J. White 1993a:3; O. Johnson 1950:35-36; Wolle 1963:287). Many of the professional miners left the area in the late 1890s, however, pulled to the far north by the Klondike gold rush.

By 1870 the population of Montana territory was declining and so was its mining output. Fifteen years later, however, all had changed; the mines in the Anaconda-Butte area were so productive they were influencing world prices. Mining in Montana then took on a new form based on industrial centers and company towns (Paul 1963:143, 148).

Prospector's Life

The General Mining Act of 1872 made mineral lands a distinct class of public lands subject to sale under prices and requirements different from other lands. Any citizen finding a valuable mineral deposit on public land was entitled to the mineral without paying the government royalty or rent. He obtained title to the minerals by staking a claim and reporting the location to county officials. He was required to spend at least $100 a year on labor and improvements. Each locator was allowed to claim 20 acres of placer ground. For lode claims, miners could claim 1500' along the vein and up to 300' on either side of the contour of the ledge. Miners and prospectors were granted free-use permits to log timber to develop their claims. Once the property was producing ore for shipment, however, they had to pay for this privilege (Dana 1980:27; Stuart 1913:157-58).

In Montana, the discoverer of a claim was entitled to one claim for discovery and one for preemption (all others were allowed only one claim). The miner had to mark the boundaries and post notices giving information on the claim. If locating a lode claim, the miner also had to sink a discovery shaft at or near the point of discovery going at least 10' vertically and/or horizontally. According to the 1872 law, a miner could obtain a patent for his claim by having it surveyed, completing at least $500 in assessment work, filing appropriate notices, and paying $5 per acre for a lode claim or $2.50 per acre for placer ground.

Prospectors generally traveled in small, organized parties of between 5 and 50 men, and they were often experienced miners from California. The prospected seasonally, because they could not work when the streams froze (Trimble 1914:97, 223-224). Once prospectors located a claim, they generally sold it before development work began, lacking the money needed to develop mines themselves.

The most common source of placer gold found in Montana was the creek placer. In creek placers, the movement of water concentrated the gold on bedrock or in the gravels just above bedrock. A prospector panning for gold checked streambeds all along his route, panned the gravel in streambeds, and pecked at rock outcroppings and examined old streambeds. When he found placer gold (versus "fool's gold," or iron pyrite) he staked a claim and recorded it. Then he might build rockers (long cradles in which the gravel and sand were rocked, the gold sinking to the bottom as water flowed through). Or, he might build sluices, long connected troughs with cleated bottoms that caught the gold particles. A sluice required large amounts of water (and thus ditches) and a crew of several men to operate.

Once the placer gold was exhausted from his claim, the miner would work his way upstream looking for the source of the gold. He would find lodes in the hills and stake off claims to outcrops, then dig prospect holes. He would also construct drifts by digging a tunnel into the bank of a gulch to reach pay gravel. Lode miners used hand drills and jacks to drill into rock. This was followed by blasting, with powder packed into each drill hole. Various technological changes improved the drilling and blasting operations.

Gold from lode mines had to be recovered by grinding or stamping to pulverize the rock. If the ore was refractory (if threads or small particles were imbedded in other rock), the valuable gold or silver had to be released by chemicals or by roasting in a smelter (Wolle 1963:15-16, 18).

The simplest way to crush the ore was by using an arrastra. The arrastra was a shallow circular pit paved with flat stones. A horse pulled a sweep attached to a heavy dragstone across the chunks of ore. When ground to a powder, the ore was mixed with water and mercury for further processing. Another method of crushing the ore was the stamp mill, which pounded the ore with iron-bottomed stamps. Silver combines readily with other minerals in its natural state, so it required a more difficult processing method than gold. After crushing, silver ore was amalgamated or roasted to form chlorides that were treated through pan amalgamation and further refined by smelting. Stamp mills and smelters required ready access to capital; lode mining is much larger in scale and capital requirements than placer mining.

Like trappers' cabins, a miner's cabin was not always very comfortable. As one old-timer put it:

As housekeepers the prospectors varied. On many a claim the cabin was as neat as a wild flower, but on some the mine tunnel was more livable than the cabin - where the dirt floor might be deep in discarded tin cans and clothing, the table never cleaned except to add a new layer of newspaper on top of the old, and the sour-dough jar green with mold (O. Johnson 1950:39).

The miner's life was often quite difficult. For example, a group of prospectors traveled to the North Fork of the Flathead from Missoula in 1867. Their leader, E. K. Jaques, was accidentally shot through both legs by one of his companions. The party camped through the winter while he healed, returning in the spring to the Flathead Valley (Buchholtz 1976a:28).

Placer and Lode Mining in the Flathead

The evidence of late-1800s prospecting and mining in the Flathead is scattered. "Dutch Lui" (also known as Luis Meyers) prospected in the northern Rockies beginning in 1885. In 1889, at the head of Copper (now Valentine) and Quartz creeks, he located a vein carrying gold, silver, copper, and some lead. This started a minor boom as footloose prospectors came in to investigate (Buchholtz 1976a:31; Vaught ca. 1943:256, 366).

Another early trip into the region took place in 1876, when Texan William Veach and four other men headed to the North Fork to prospect. They prospected and trapped in the Logging Lake area, finding a 30-ounce nugget of gold near Quartz Lake and building a cabin there. Veach was the hunter and cook for the group; subsequently he returned to Texas (Veach 1939).

Evidence of very early prospecting was found in the area of Doris Creek off the South Fork, where hunters in 1898 found an old cabin with an adit nearby and piles of quartz studded with wire gold. Early prospectors also set up an arrastra to crush the ore on Fawn and Wounded Buck Creeks (there were probably others) (Green 1972 IV:122, 129, 131).

There has been quite a bit of mining activity northwest and southwest of Kalispell over the years. A sluice box and a diversion dam were installed on Herrig Creek west of Ashley Lake, for example. The Flathead Mine in the Hog Heaven district southwest of Kalispell was discovered in 1913 but remained idle until lessees discovered the main ore body in 1928. The Anaconda Copper Mining Company soon took over the lease and shipped high-grade ore intermittently, with most of the value in silver (they did not ship between 1930 and 1934 because of low silver prices). In the mid-1940s the mine was employing about 75 men. Three or four other mines were operating sporadically at that time, including the Ole Mine, about a mile directly west of the Flathead Mine, which had values in gold, silver, and lead (this was later developed again in the 1960s). The mine that produced more than 90% of the ore in the district, the Flathead Mine, closed in 1946 (Johns 1970:85, 137, 141; Sandvig 1947:35, 38; Sundborg 1945:59-60).

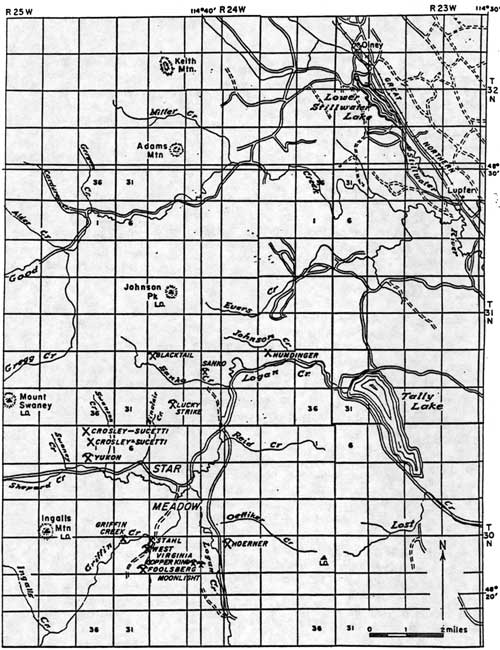

Several productive mines during the historic period were located in the Star Meadow mining district (see Figure 9). The Sullivan mine, which opened in the early 1890s, was located about 10 miles from Tally Lake. The copper ore was packed out by horses, but eventually the promising lead was cut off by a fault. In 1925 Glen Sucetti re-opened this mine and found a new lead of ore, and by 1934 he had constructed some buildings at the site ("Flathead's Mining" 1931:5; "Development" 1934:8).

|

| Figure 9. Star Meadow mining district, showing locations of mines (Johns 1970:132). (click on image for a PDF version) |

Other mines in the Tally Lake area were located in the vicinity of Logan Creek (named for miner and attorney Sidney Logan) and Sanko Creek (named for miner Fred Sanko). The Foolsberg and the West Virginia Mines were located on the ridge between Sullivan and Griffin Creeks. The former was developed in 1920, the latter in the 1890s. The Blacktail prospect was discovered after the 1936 Sanko Creek fire burned the vegetation that had been obscuring the copper-containing vein. A few other claims in the Star Meadow district produced some ore in the 1920s and 1930s. The valuable ore contained copper with some gold and silver. Many other mines were developed but never went into production ("Tally Lake RD List of Names "in TLRD; Johns 1970:131-37).

The South Fork of the Flathead also had numerous mining claims for a time. In 1892 a local newspaper boasted that the South Fork "is now supposed to be one of the richest mineral regions in the State." In 1891 Baptiste Joyal and William Curran toured the South Fork, finding copper, silver, and gold, plus coal beds. By 1898, however, no ore had been shipped from the valley, and a surveyor passing through noted only about six cabins that were occupied seasonally by prospectors doing their assessment work. In 1913 another boom hit the South Fork, this time because of a copper strike about 35 miles south of Coram, with Felix Creek running through the center of the claims (Johns 1943 VII:39; Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:73; "Flathead Copper" 1913:1).

Baptiste Joyal (also known as XJoyal, Zeroyal, Zeroyle) trapped in the South Fork and was one of the first Euroamericans to live in the area. Like other prospectors, Joyal sometimes earned extra cash by working as a guide for miners. He guided two prosperous California miners across the Rockies by going up the South Fork and down the Sun River (Opalka 1983; Shaw 1967:46). Joyal died in the winter of 1909 in his cabin on Hoke Creek.

Another French-Canadian South Fork prospector was Felix Drollette. He worked Felix Basin and was the original prospector in Silver Basin, at the head of Logan Creek. A man named Harris had a cabin at the junction of Felix and Harris Creeks, and he had mine shafts at least 8 miles up the creek. Harris set up a tent camp in the Coram area, built a bunkhouse and a messhall in the area of the mine, and hired men to prospect the Hoke/Baptiste area, but he found only copper stain, no ore (Opalka n.d.; Opalka 1983; Martin 1983; Green 1972 IV: 133).

Farther up the South Fork, Levi Gaustadt filed a barite claim in 1958 on Black Bear Creek. Although the material was assayed as highly productive, the claim was never patented (Shaw 1967:22).

Prospectors spent long weeks searching the drainages of the Middle Fork of the Flathead for valuable minerals with little success. In 1899 there were reportedly several new claim stakes between Bear Creek and Java, and some copper claims were staked in 1898 on Summit Creek not far above Java. Several miners staked claims near Bear Creek on the Middle Fork, including Kalispell attorney Sidney Logan and nearby homesteaders Louise and Philip Giefer. Some mining claims were also located in the Belton and Essex areas (in fact, Almeda Lake may be named for a woman named Almeda who was listed as a mine claimant) (Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:37; Ayres "Flathead" 1900:313; Holterman 1985:19-20, 45).

Two French-Canadians named Pauket prospected in the 1890s all over the Flathead area. They located claims on Deerlick creek near Nyack in the Middle Fork, driving an adit in the face of a cliff. They spent a winter in Butte, as many Flathead miners did, and the next year sold out for $8,000. In 1934 a claim near Garry Lookout above Nyack was worked, causing a minor rush of prospectors to the area, but most abandoned their prospects (Green 1972 IV: 134, 141).

Northeast of Eureka, prospectors staked several copper-silver-lead claims in the 1890s in the Bluebird Basin. During the summer of 1894, 12 men worked on the mine and shipped ore to Great Falls for processing. Profits were low over the years, and development plans were curtailed with the coming of World War I. In 1912 a mining claim was located near Upper Whitefish Lake with men digging a prospect tunnel 155' deep into the mountain. A little earlier, in 1905, the Lupfer Mining Company had claims eight miles northwest of Whitefish, but this company disappeared within a year. Charlie Oettiker, who homesteaded on Oettiker Creek, claimed to have found gold, silver, platinum, and uranium in an outcrop behind his cabin (O. Johnson 1950:37-38; Shea 1977:117; "Prospect Tunnel" 1912; Schafer 1973:67; Boettcher 1974:221). Other miners started excited rumors about finds, but the real money was actually made in real estate.

Very little prospecting or development work was ever done in the Swan Valley. In 1899, H. B. Ayres reported that there was no mining work or prospecting in the Swan. In 1908 Joe Waldbillig filed a mining claim at the mouth of Holland Lake, but he probably never worked it. There are a tunnel and track east of Owl Creek and abandoned mines on the west slopes of the Swan Range farther north, in the Lake Blaine area and on Columbia Mountain. One prospector who spent every summer in the Missions for 30-some years, reported that "all I got is a sore back" (Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:80; Wolff 1980:53; Beck 1981).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap3.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |