|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

FIRE DETECTION, SUPPRESSION, AND PREVENTION

Introduction

By the turn of the century Americans had lived through - and remembered - several wildfire complexes that caused tremendous devastation. For example, the 1871 fires in Wisconsin burned 256,000 acres and killed at least 1,000 people. The 1889 fires in Montana burned an estimated 88,020 acres, but much of the area had not yet been settled and so the effects were not so dramatic (Ensign 1889:82). The 1910 fires, in contrast, swept over approximately 3 million acres in Montana and Idaho, causing great destruction of property and loss of human lives.

Wildfires in the mountains and foothills of the northern Rockies are a regular summer occurrence, and the signs of their passage mark burn areas for many years (see Figure 62). For many Flathead National Forest employees, the work year has always been divided into "fire season" and "the rest of the year." After the 1910 fire season, the Forest Service went on the offensive, setting up fire detection points on high peaks and ridges, aerial patrols, and better transportation and communication systems.

|

| Figure 62. South Fork road near Wounded Buck Creek, 1926, Great Northern Mountain in background (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

Fire detection efforts focussed on ground patrols from the many lookout points established in the area and even from railroad speeders. Fire suppression efforts involved large numbers of men working on the firelines, smokejumpers dropping from planes into remote areas, and a variety of firefighting techniques and tools. The Flathead National Forest cooperated with the state forests, Glacier National Park, lumber companies, and the railroads. An association of private forest landowners, the Northern Montana Forestry Association, also cooperated with the Forest Service and other agencies in detecting and fighting fires in northwestern Montana.

All these efforts at fire control resulted in dramatically reduced acreages burned by wildfire since 1910. This has led to subsequent problems with fuel build-up due to unnatural conditions, and Forest Service fire policy is now shifting away from the earlier "fight all fires at all costs" policy. The vegetation of the Forest has changed greatly due to decades of fire suppression. Above 5,000', the suppression of the frequent lightning-caused fires has changed the age class of the trees over the years. At lower elevations, frequent low-intensity fires that burned the undergrowth but did not kill the larger trees have been replaced by higher-intensity, less frequent fires that often end up replacing a ponderosa pine/western larch forest, say, with even-aged lodgepole pine. According to a Forest Service report, the Flathead National Forest today has "old-growth" conditions on only 2.8% of the Forest land below 5,000' in elevation that is capable of producing old growth. The total old growth for the Forest (including higher elevations) is 17.6% (FNF "Summary" 1992).

The evidence of historic wildfires is everywhere on the Forest, in the form of snags, changed vegetation, fire camp sites, old firelines. Fire detection has changed dramatically over the decades. Today, only a few lookouts on the Forest are regularly manned, and many have been destroyed; all that remains is often the dump, concrete pylons, phone wire, and depressions indicating locations of buildings and structures. Several fire lookouts from the historic period are still in good condition and can evoke the time when lookouts would play music to each other at night over the phone system. One of these is Hornet Lookout in the North Fork, which has been restored and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. This log lookout with a cupola dates from 1923, and it has recently been opened to the public as a part of the cabin rental program. Three structures on Coal Ridge in the North Fork - a cabin, a lookout building on a pole tower, and a platform - are still standing and provide a unique reminder in the area of the variety of lookout structures in use over the years.

Fire Behavior and History

Over the years, the great majority of fires on the Flathead National Forest have been caused by lightning rather than by human activities. In the northern Rockies, about one lightning stroke in 25 has the characteristics needed to start a fire (Pyne 1982:9). Major fires have burned large areas of northwestern Montana. Large fires in 1910, 1919, 1926, 1929, and more recent years have replaced much of the Forest's vegetation (see Figure 63).

| 1885 | Lake Blaine to Doris Mt. (7,000) | |

| 1889 | various locations | |

| 1903 | Crossover Mountain | |

| 1903 | Limestone Cabin area, and Milk, Whitcomb, and Upper Twin Creek | |

| 1903 | Hart Basin | |

| 1910 | Schafer (120,000-150,000) | |

| 1910 | Wounded Buck (2,500) | |

| 1910 | White River (100,000) | |

| 1910 | Crossover Mountain | |

| 1910 | Lost Johnny to Middle Fork | |

| 1919 | Bear Creek south of Java (30,000) | |

| 1919 | Sheep Creek to Long Creek | |

| 1919 | Sullivan Creek (17,000) | |

| 1919 | upper White River | |

| 1919 | Kah Mountain (2,500) | |

| 1919 | west side of Swan River (50,000) | |

| 1926 | Lost Johnny to Middle Fork (2,560) | |

| 1926 | North Fork (23,000) | |

| 1926 | Big Prairie | |

| 1926 | Tally Lake Ranger District | |

| 1926 | Good Creek | |

| 1929 | Half Moon (103,000) | |

| 1929 | Swan Valley | |

| 1929 | Soldier Creek | |

| 1929 | Sullivan (35,000) | |

| 1929 | Trail Creek | |

| 1931 | Lost Creek | |

| 1934 | Swan Valley | |

| 1940 | Sanko Creek | |

| 1946 | Big Lost Creek | |

| 1958 | Coal Creek (2,900) |

| Figure 63. List of some of the major fires in the Flathead National Forest area. Acres burned are given in parentheses when available (FNF "Timber Management, Coram":40; Wolff 1980:54; Graetz 1985:101; Arvidson 1967; Shaw 1967:86-87; GVRD 1981:16; 24FH41, FNF CR). |

In 1899, H. B. Ayres traveled through the Flathead and Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserves reporting on their resources. In his admittedly hasty survey, he estimated that 90% of the Swan/Clearwater Valley had been burned in the past 100 years. The western slope of the Swan Range south of Swan Lake was almost bare at that time. In the Middle Fork, about 50 square miles had been burned severely and repeatedly (Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:78; Ayres "Flathead" 1900:315).

Ayres described the South Fork as having about 310 square miles burned over severely, mostly in 1889. Most fires in the valley, he felt, were set by Native Americans, other hunting parties, or prospectors. About 90% of the new stock was lodgepole pine. He estimated that about 1/3 of the Lewis & Clarke forest reserve had been recently and severely burned, and said there was a little less than 1,000 board feet per acre of merchantable timber on the reserve (Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:15-16, 72).

Several early reports mention Native Americans setting fires, presumably to drive out game or to keep meadows open. One Kalispell resident claimed that he saw Native Americans set 25 fires in the Swan Lake area (W. H. Griffin to Gust Moser, 14 August 1900, entry 44, box 4, RG 95, FRC).

The coming of the railroads to Montana dramatically increased the number of fires all along the railroad lines. According to Ayres, in 1898 the hills along the Middle Fork were almost barren because of fires, most of which were started during the Great Northern Railway construction or from sparks, cinders, or campfires along the line since. Less than 20% of the extensive burns had restocked with any species of trees (Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:67).

Early GLO and Forest Service Fire Policy

In 1901 the Secretary of the Interior issued a statement outlining management practices for forest reserves, mentioning that "the first duty of forest officers is to protect the forest against fires." In that era, however, the only models of efficient wildland fire protection in the United States were the fire warden system in New York and the military patrol system in the national parks. Until the 1910s, fire protection on the national forests was limited by inadequate manpower and relatively poor transportation and communication facilities. The Forest Service had to rely on permittees, settlers, and railroad section gangs for temporary firefighting manpower. The equipment was minimal by today's standards; a typical early fire guard patrolling in Montana carried a canteen, a canvas water bucket, a shovel, and a carrying case with some food (Pyne 1982:231-232, 236).

In a classic example of the Washington Office's misunderstanding of the job facing western forest rangers, the GLO stated in 1902 that supervisors and rangers would be held personally responsible for any fires they allowed to escape on their forest reserves without adequate explanation. In 1907 on the Lewis & Clark National Forest, each forest guard covered about 120,000 acres (Clack 1923a7). The 1902 letter stated:

It is not understood why forest fires should get away from the rangers, or rather why they do not find them and extinguish them more promptly. It seems reasonable that a ranger provided with a saddle horse and constantly on the move, as is his duty, should discover a fire before it gains much headway. This statement is made knowing that some of the rangers' districts are extremely large ("Sixty Years Ago" 1963:533).

In 1908 the Forest Service prepared systematic fire plans, appropriations increased available manpower, and an act allowed for deficit spending to cover the cost of fire emergencies (Pyne 1982:236). These measures were not nearly enough, however, to prepare for the 1910 fire season.

1910 Fires in the Northern Rockies

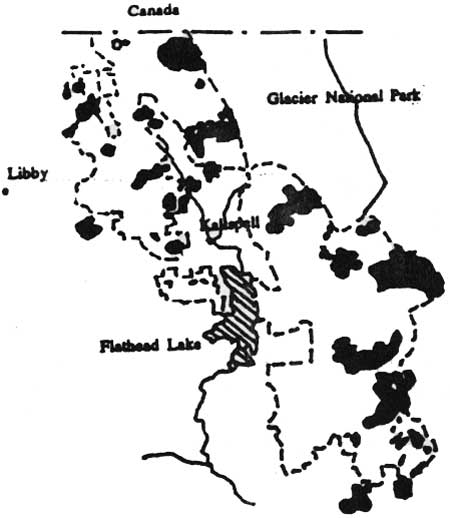

The 1910 fires laid waste to some 3 million acres of land in Idaho and Montana (see Figure 64). The devastation left behind by these fires in northern Idaho and Montana marked a turning point in Forest Service management of the national forests. As fire historian Stephen Pyne put it, "The Northern Rockies fires of 1910 left a burned swath across the memory of a generation of foresters." Fire protection immediately assumed a prominent, overwhelming role within the Forest Service (Pyne 1982:239).

|

| Figure 64. Areas burned on Blackfeet and Flathead National Forests In 1910 fires (from Cohen 1978). |

The 1910 fires, fanned by hurricane-force winds, killed at least 85 people. None of these fatalities was on the Flathead fires, but four firefighters died on the nearby Cabinet National Forest. One 30-man fire crew under the supervision of ranger Peter DeGroot was trapped by flames west of Olney. The fire camp burned, but the men managed to find an escape route by wading through the hot ashes of a burned area (Cohen 1978:v, 76; Kalispell Bee, 23 August 1910).

The first fire of 1910 started on the Blackfeet National Forest on April 29, and by late June fires were burning in all the Forests of Region One (Cohen 1978:11). The 1910 fires took on frightening dimensions on August 20 and 21, when gale winds (the "Big Blowup") created fast-moving crown fires. According to Pyne:

Winds felled trees as if they were blades of grass; darkness covered the land; firewhirls danced across the blackened skies like an aurora borealis from hell; the air was electric with tension, as if the earth itself were ready to explode into flame. And everywhere people heard the roar, like a thousand trains crossing a thousand steel trestles (Pyne 1982:246).

In 1910, 65% of the fires were caused by railroad operations, the rest by slash burning, lightning, campers, prospectors, and perhaps arsonists. Only one lumber company in Flathead County helped fight the fires. Glacier National Park estimated that as many as 75% of the fires in the Park were set by "hoboes and others who want work" (Moon 1991:42, 44; Pyne 1982:243).

The most damage, however, resulted from fires that started in remote locations, ignited by lightning (Pyne 1982:243). This was certainly the case in the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests in 1910. Fires that started in low ground, along railroads and trails, or in inhabited areas were easier to control promptly. Other fires, mostly started by lightning, could not be reached quickly, and when the wind began to blow those fires "swept down in solid fronts miles in extent and destroyed the work of weeks of fighting." One writer described his frustration at fighting the fires in 1910 in the Swan Valley:

A trail must either be cut out to a point near enough to reach the fire from camp or the horses taken slowly and painfully through country covered with tangles of down timber and dense thickets, with the risk that in case the fire got well started there might be some difficulty in getting out again. Meanwhile the fire is gaining headway, and the ranger finds on reaching it that he can make no impression on it and needs 20 to 50 men to control it. He proceeds to the nearest telephone station and the men are sent in from some town, or in rare circumstances they may be recruited from settlers nearby. Their beds, provisions and cooking outfit are packed in 20 to 75 miles on animals hired for the purpose, and after a delay of from 3 to 7 days they reach the fire.

By this time it is so large that they cannot entirely subdue it (Chapman 1910:638).

Fire crews on the national forests were supplemented with men from Missoula, Spokane, and Butte until the supply of floating labor had been exhausted. Kalispell's two militia companies were under the jurisdiction of the state forester. The Forest Service also received help from the regular Army. Three companies were dispatched to the Flathead National Forest, others to the Coeur d'Alene and Lolo National Forests. They worked on fires along the South Fork, the Middle Fork (Stanton Lake area), and in Glacier National Park. They provided medical supplies, surgeons, and pack trains as well as firefighters. The Region had no reserve of fire equipment then, so new equipment was purchased as crews were sent out until the supplies in many stores were exhausted (Kalispell Bee, 16 and 23 August 1910; Pyne 1982:244; Koch ca. 1942:2).

Local settlers did help fight the 1910 fires. In the North Fork, for example, Forest Service ranger Frank Liebig was able to recruit virtually all the settlers to help with a fire in the McGee Meadow area, but even so half a dozen of them lost their homes and possessions to fire. He also received help from the Army and the militia. That particular fire was finally put out by rain (Vaught Papers, 1/L).

Many forest rangers in the Flathead area talked about the shortage of men, horses, and supplies in the 1910 fires. For example, R. L. Woesner was assigned to an area near Stryker and faced continual fires along the railroad tracks. He was sent about 60 men and then a company of soldiers from Fort Harrison, but the crew only had two old government pack horses with sprung knees to move their fire camp, located about five miles from a road (O. Johnson 1950:266).

Glacier National Park was created in 1910 and its new administrators immediately faced the disastrous fire season of that summer. Forest Service rangers continued to work in the Park during that summer. In mid-July firefighters from the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests were sent to help the Park, which had no money appropriated to protect its forests from fires. Nineteen thousand acres burned in the Park that summer (Buchholtz 1976b:26; Cohen 1978:11-12).

Firefighters in the Park faced the same difficulties of transportation, communication, and shortage of supplies as did those in the Forest. In July of 1910, forest ranger Liebig spotted two fires in the new Park. According to his own account, he:

marked the fires down as close as I could and thence went back to the Ranger camp on the head of Lake McDonald [from Lincoln Peak], had just time to send a message with the big boat to Sup. Haines in Kalispell to inform him of the fire in and around Harrison Lake, thence, had a bite to eat, and went to the pasture on Johns' Lake and got two more horses (Liebig 1910:9).

Sometimes there was conflict over jurisdiction, and the interagency spirit of cooperation faded. When a fire in the Essex area was reported to the forest ranger at Essex, he remarked that it was "out of his jurisdiction"; it took several days before any effort was made to put that fire out (Logan 1911).

In August of 1910, Supervisor F. N. Haines of the Blackfeet National Forest was sounding close to despair:

We have made a hard fight, but it looks now like we have lost. There is absolutely no show to even control the fires, and the best we can do is to check them here and there as best we can and wait for rain (Elwood 1980:150).

Rain and cooler temperatures ended the disastrous fire season of 1910. As late as February of 1911 snags were still smoking from the previous season, sticking up through 5' of snow (USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:195).

The 1910 fires destroyed an estimated 7-8 billion feet of marketable timber. Subsequent timber management consisted of fire salvage sales (although much of the burned timber was too remote to log), replanting burned sites, control of insect and disease outbreaks, reducing erosion, and snag felling as a fuel modification measure. Many surveys had to be redone because the witness trees had burned. Subsequent efforts to develop the woods to prevent future similar destruction made the Forest Service, particularly Region One, a national leader in fire protection (Pyne 1982:249-250; Koch ca. 1942:22-23).

A 1910 Forest Service report stated:

It has been accepted generally as true that one of the main reasons for the disastrous forest fires of the past season was that they started in inaccessible places or portions of the forests which were not regularly patrolled. Also, that had the Forest Service been given a sufficient amount of money for the construction of the necessary trails and telephone lines and for a better patrol, many of the fires would not have spread (quoted in Baker et al. 1993:224).

Fear of an imminent timber famine, heightened by the 1910 fires, led the Forest Service to push for more funding and support for its fire control program. The needs of fire detection and suppression (roads, trails, telephones, etc.) were a large factor in settling the remote mountainous areas of the northern Rockies. The winter following the 1910 fires, a fire plan was developed, and it became policy on the Flathead National Forest that all forest guards were to be used primarily on fire protection work in July and August (Clack 1923b).

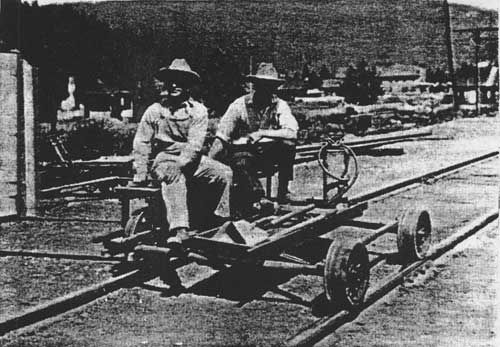

Another result of the 1910 fires were a number of technological innovations, some of which are still in use. The new equipment included the Osborne fire finder, the Pulaski (combination ax and mattock), and a railroad speeder car equipped with a bicycle seat, pedals, and rubber tires (Caywood et al. 1991:28).

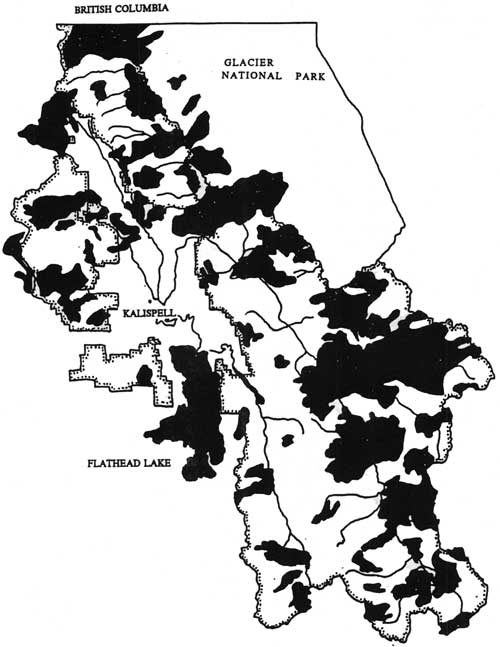

Because of increased efforts at fire detection and suppression, the acreage burned in Montana declined dramatically after 1910. Even so, much of the Flathead National Forest burned between 1889 and 1949 (see Figure 65). In the 1940s, the amount burned was only 3% of that burned in the 1910s, as shown below:

| 1910-1919: | 1,834,000 | acres |

| 1920-1929: | 364,000 | |

| 1930-1939: | 150,000 | |

| 1940-1949: | 53,000 |

(Montana Conservation Council 1954: 10)

|

| Figure 65. Areas burned by major fires on the Flathead National Forest, 1889-1949 (base map 1939, FNF CR). (click on image for a PDF version) |

Fire Detection

In the early years of the forest reserves/national forests, fire patrols were woefully inadequate. For example, forest ranger George Rhodes at Belton wrote to his supervisor in Ovando in 1904:

I will keep a very sharp look for fires I assure you[.] as there is only about 12 miles of my district in which I can use a Saddle Horse at present I have to make the trip on foot from Belton to Nyack[.] there is a Trail along the Rail Road but it has not been open for years and it will require a good lot of work to open it up but it can be done when there is no danger from Fire (Elsethagen, FNF Class).

Every means possible for fire patrol was tried. Even boats on Flathead Lake and Tally Lake (and perhaps others) were used for fire patrol and for smokechasing, but this was a slow method and the fire guard could not go out in lightning storms due to rough water. On the east side of Flathead Lake, the fire guard stationed at Upper Beardance for many years would travel to various observation points in a Model A Ford coupe. Boys even patrolled in buggies; Joe Opalka was hired in 1917 at the age of 15 to patrol the road between Bad Rock Canyon and Coram by horseback or by horse and buggy for $4.00 a day (FNF Lands; Fred Hartson interview, 23 December 1991, TLRD; Robbin 1985:113-114; Opalka reminiscences, FNF CR).

The most effective method of fire patrol along the Middle Fork was the railroad speeder, used by forest rangers and guards in the area for many years. In 1906, Forest Service inspector Elers Koch commented that the speeder was "an unqualified success. One man on a speeder can patrol several times the area that he could on foot or horseback, and can have his tools and camp equipment with him at all times" (see Figure 66) (28 November 1906, "Reports of the Section of Inspection, entry 7, box 4, RG 95, FRC).

|

| Figure 66. Railroad speeder in use by Forest Service workers near Warland, Montana, 1921 (photo by K. D. Swan, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Regional Office, Missoula). |

The established method of fire patrol in the fall of 1907 was to patrol the trails, roads, ridges, and railroad lines and to station men as near as possible to the bases of high peaks so they could climb the mountains each day. Six forest guards worked in the South Fork from Coram to Big Prairie. They patrolled the main South Fork trail looking for fire "and incidentally cutting out fallen timber." In a meeting that fall everyone agreed that this system did not work because guards needed to climb to a high point each day. So, beginning in 1908 men were stationed where they could climb to lookout points, sometimes moving between two different peaks on alternate days (Clack 1923a:7; Clack 1923b).

In 1909 the Lewis & Clark National Forest was divided into eight ranger districts, and each was allotted about three men. Forest officials felt they were getting prepared for any fire situation. But in 1910, with virtually no communication system, this force of men proved to be "totally inadequate." On the Bunker Creek fire in 1910, for example, the ranger augmented his force of three men by riding to Coram for 10 more men, but by the time they got to the fire they needed 100 men (Clack 1923b).

At a supervisors' meeting held in 1910 (before that year's disastrous fire season), the men discussed selecting lookout points and patrol routes and coordinating these between ranger districts and Forests to aid in locating fires. Also discussed were the ideas of building "shot gun" trails of minimal standard, just enough for pack horses to travel, and building temporary phone lines to the lookout points so that patrolmen could get help more easily in case of fire. They also planned to distribute tool caches throughout the forests for fire use and to provide men in remote districts with supplies and food so they did not have to leave the Forest to obtain needed supplies. The main objection to putting men on lookout points in 1910 was "the difficulty of securing a man who would put up with the monotony and isolation incident to such a position." Region One supervisors thought it would be best to alternate the lookout men with those doing ridge and trail patrol work ("Report of Supervisors' Meeting, 3/21-26/1910," 1360 meetings - Historical - Early Supervisor Meetings, RO).

Some early Flathead forest rangers promoted the idea of lookouts and lookout points before their supervisors approved of the idea. According to Joe Eastland, an early forest ranger along the Whitefish Divide, a Sir J. C. Davis came to the national forest from London to collect seeds of ponderosa pine, white pine, and alpine larch. He told Eastland about the fire lookouts in Scotland and England, and Eastland subsequently tried to convince forest officials of the advantages of posting lookouts along the Whitefish Range. Frank Liebig, stationed in the Lake McDonald area beginning in 1902, reported climbing Mount Stanton to look for fires and being kidded by his fellow workers for doing so (O. Johnson 1954:12-14; Vaught Papers 1/L).

In 1912, Montana forest rangers located fires with field glasses, plotted them on a map, and then phoned other guards. By that time the Forest Service also had "watch stations" (or lookout points) from which signals could be made by waving flags, flashing the sun's rays from mirrors, or using gasoline torches. Some were provided with a railed platform, perhaps enclosed. The "forest watchers" were provided with field glasses and a signal mirror (probably a heliograph) and were located so they could be seen from a ranger or guard station, where a ranger was "continually on duty during the day to look for signals." These watch stations reportedly had a range of 25-50 miles (Willey 1912:57).

In the early years, lookout points had no improvements built on them. The lookout man would camp in the nearest sheltered place below the lookout point and would hike up to make his observations. Sometimes the lookout man would travel between two different points to observe more area; he would then be following a patrol route, with special emphasis on high-danger areas such as the railroad right-of-way, camp sites, lightning zones, etc. (USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:1; "Report on Felix Creek Fire, 1914" 1914 Fires Flathead, RO:4).

The difficulty of fire detection and fire control in the early 1910s is exemplified by the efforts to control the Felix Creek fire in 1914 on the Flathead National Forest. In that year, the few fire guards scattered throughout the forest were equipped with a map of the Ranger District, a compass, and a pair of field glasses. No map boards or alidades had yet been set up, and the few lookout points had no improvements. A lookout stationed on Mount Aeneas first reported the Felix Creek fire to the Echo Ranger Station by phone. The ranger then rode 4 miles to the nearest phone to call the Supervisor's Office, which called the ranger at Coram because they could not reach the ranger on the lower South Fork. Coram got the message through to the guard at Riverside at suppertime, and the guard found the ranger at a campsite. At about 8 p.m. the guard at Coal Banks was called and told to go to the fire. The guard could not find the fire, but a trapper reported the location. Sixty hours elapsed between the time the first men were ordered and any actual firefighting began. All food for the fire camps was ordered by phone through the Supervisor's Office (see Figure 67). Cars were rented in Kalispell to rush supplies as close as possible to the fire camp, and local merchants provided supplies based on emergency lists they had been given at the beginning of the fire season ("Report on Felix Creek Fire, 1914" 1914 Fires Flathead, RO:4).

|

100 lbs. flour 5 lbs. baking powder 10 pounds salt 2 5-cent packages yeast 1 lb. soda 10 lbs. cornmeal 20 lbs. rice 80 lbs. ham 20 lbs. bacon 25 lbs. potatoes 10 lbs. onions 20 lbs. beans 10 lbs. coffee 1 lb. tea 48 cans milk 40 lbs. gran. sugar |

10 lbs. brown sugar 5 lbs. dried peaches 5 lbs. dried apples 5 lbs. dried prunes 5 lbs. raisins 12 lbs. canned butter 1 gallon vinegar 12 cakes ivory soap 2 dozen candles 0.5 pint vanilla extract 0.5 pint lemon extract 0.25 lb. pepper 0.25 lb. mustard 15 lbs. lard 10 lbs. oatmeal 5 boxes matches |

| Figure 67. List of emergency rations ordered by the Flathead National Forest during the 1914 fire season. These figures are the supplies ordered for a 10-man crew for 10 days. The total weight was reported to be 575 pounds ("Report on Felix Creek Fire, 1/1411915," 1914 - Fires - Flathead, RO:12). |

Lookouts were located so as to maximize the "seen area" of the forest. In 1929, 15% of the fires on the Flathead National Forest started in unseen areas (35% of the forest was considered unseen at that time) (see Figure 68) (Hornby 1931:5).

|

| Figure 68. "Seen area" photograph taken from Standard Lookout (Glacier View Ranger District). These photographs were taken in the early 1930s from improved and unimproved lookout points. "Seen area" maps were used to determine which combination of points afforded the greatest area of detection coverage. They also helped in determining the need for and height of a lookout tower (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Columbia Falls). |

Crow's nest lookouts were an early, relatively easy-to-build form of lookout. They were built all over the Flathead National Forest, from Yellow Bay Mountain on Flathead Lake to Reid Divide in the Stillwater area. The observatory was a platform accessed by a ladder up a tree. "Lookout trees" were used into the 1930s. On the Tally Lake ranger district, for example, in 1930 they were spaced 1-1/2 miles apart and featured 12" spikes driven into either side to act as a ladder for smokechasers, with climbing branches above. Sometimes three or four trees growing close together would support a platform and map stand, but generally lookout trees were single trees (Robbin 1985:114; Taylor 1981; Taylor 1986).

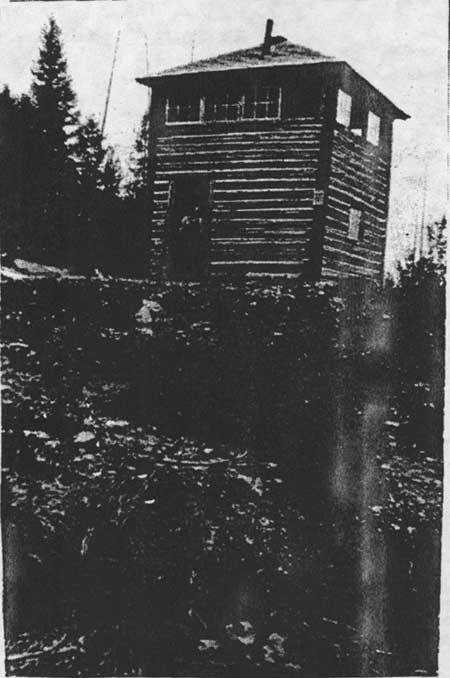

The first Forest Service lookout was built on the Cabinet National Forest. The earliest lookouts were small, crude log cabins used to house the men stationed there. If no suitable trees were available for a crow's nest, the men built a tower out of poles (Caywood et al. 1991:28; USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:2). The 10' x 10' lookout platform on Coal Ridge in the North Fork is one of the few lookout platforms still standing in Region One.

The first permanent lookout building on the Flathead National Forest was built on Spotted Bear Mountain in 1914 (this was replaced in 1933) (see Figure 69). The Forest Service did not have enough funds for more than a few high lookout cabins until the 1920s (trails, roads, and phone lines had a higher priority in the early years). The Forest built more and more lookouts, especially during the 1930s, until in 1939 there were 147 lookouts and towers on the Flathead National Forest (see Figure 70). By 1930, approximately 800 peaks or points were occupied in Region One (Caywood et al. 1991:30, 38; "Transportation - Fire" 1931:13; Shaw 1967:7; FNF "Informational Report" 1939).

|

| Figure 69. Jim Creek lookout, 1923. This lookout was identical in style to the original Spotted Bear lookout, built in 1914 (courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

The construction of permanent buildings on lookout points enabled the Forest Service to attract better men to the job. As Flathead National Forest employee J. G. McDonnell commented, with the new lookouts "A man can observe the area he is responsible for even while preparing his meals, and the necessity of first routing out the ants and rodents, and running out during the process to pile a few more rocks on the tent to keep it from blowing away is done with" (McDonnell 1937:36).

The first standard Forest Service lookout was the D-6 pyramidal-roofed cabin with cupola, developed in 1915 and popular until the mid-1920s. In 1922 the Flathead National Forest developed the D-1 cupola house, designed by Dwight L. Beatty, which was 14' x 14' instead of 12' x 12', built of logs, and had a gabled roof (the lookout building on Hornet Mountain, built in 1923 and still standing, is a good example of this design) (see Figure 71) (Caywood et al. 1991:107; Kresek 1984:11-12).

|

| Figure 71. Hornet Mountain lookout, 1923. The log cabin with the cupola was new and soon replaced the earlier platform and cabin shown in the photo (courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

Clyde Fickes and architects at the Regional office were assigned the job of designing a tower and lookout house combination that would allow a lookout to be at his post 24 hours a day. Plans developed by other Forest Service regions were too expensive for Region One to use. In the spring of 1928 Fickes built a sample 12' x 12' lookout with a cupola on the Lolo National Forest. The materials weighed approximately 6,000 pounds (if fir and pine were used), and it took 25 man-days to build. It was designed to be built by a couple of men who could read instructions and who had a hammer, screwdriver, and level ("New Type Lookout" 1928:14; Fickes 1973:83-84).

Fickes developed standard plans for a lookout building with a gable roof and windows on all sides known as the L-4 (see Figure 72). The popular model offered improved efficiency because the lookout did not have to climb up and down the ladder to the cupola. The earlier versions have gabled roofs, those dating from 1933-53 have hipped roofs. In 1930, the Forest Service invited bids for enough lumber to build 100 L-4 lookout houses, which would be cut and bundled for packing in Spokane and delivered from the Spokane warehouse. The pre-cut cabs generally cost $500 (the towers were built from pole cut on the site). The Superior Building Company of Columbia Falls began providing the Flathead National Forest with pre-cut materials for 14' x 14' L-4 lookouts in 1929. In 1930 three were assembled on the Forest (Bruce Ridge, Desert Mountain, and Ingalls Mountain), and they reportedly could be set up by two men in just three or four days. The company's lookouts were assembled almost entirely without nails, similar to the ready-cut garages and small houses the company provided for the housing market (USDA FS "Early Days" 1976:3; "Lookout Houses" 1930:9; Fickes 1973:84; "New Ready-Cut" 1930:10; "New Ready-Cut" 1929:2).

|

| Figure 72. L-4-style lookout on Flathead National Forest peak (photo by Toussaint Jones, courtesy of Flathead National Forest). |

Between 1934 and 1941 Region One also used a prefabricated 7' square cab with sheet metal walls on steel towers. The lookout did not live in the building; he or she used it for observations only. Other standard plans modified the size and design of the L-4 slightly. Heavy galvanized steel towers were introduced in the 1930s; Aermotor of Chicago, a windmill company, was the main provider. Since 1953 standard Region One lookouts have been built with flat roofs, and road access has allowed many to have concrete or cinder block foundations. Other Forest Service regions and other agencies developed their own designs (Caywood et al. 1991:107; Kresek 1984:11-12).

Some lookouts were built in response to bad fire years, such as the Holland Lookout built after a 1919 fire complex burned approximately 50,000 acres in the Swan Valley. In 1920, however, a Forest Service inspector reported that the fire detection system on the Flathead National Forest was still "casual." Not one smokechaser on the South Fork had a fire pack ready to go, he wrote. Some of the maps at lookouts could not be permanently oriented, men did not know the country or the locations of other lookouts, fire tools were dull, and some "seen areas" had no maps available (Wolff 1980:54; 19 July 1920, Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC).

The Forest Service provided the food for the lookouts, almost all of which had to be nonperishable. A typical supply included: flour, baking powder, salt, sugar, coffee, beans, rice, dried apricots, prunes, raisins, ham, bacon, canned corned beef, dehydrated potatoes, canned corn, tomatoes, milk, and syrup. The later addition of canned fruit and apple butter was considered "high living." Lookouts routinely supplemented their diet with fish and huckleberries, when accessible, and with grouse (USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:2).

Most of the rations at a lookout were packed in small cans. Lookouts considered it amusing to post a fire slogan reading "Stay With It 'Til It's Out" inside the outhouse door. In the early 1930s lookout rations were packed in wooden boxes, each holding about 125 pounds of food, in units for 30, 45, or 60 man days. The packer supplemented these pre-packed rations with potatoes, bacon, eggs, and onions just before leaving for the lookout. Tally Lake lookout Norm Schappacher recalled that in the 1930s "There was this brown bread that came in a can - we'd usually throw it at the bears. But the butter in cans, you could eat almost anything with that butter in it" (Howard 1984; Taylor 1981; "Lightning" 1987).

In the mid-1930s it was realized that all lookouts came out of their towers at about the same time to cook meals, during which time there were practically no observations being made. So, each lookout was then assigned a 15-minute intensive observation period per hour, staggered to keep the area under constant observation. Lookouts had to record lightning strikes day or night, and they were not paid overtime (Taylor 1981).

Lookouts were required to be within hearing distance of the phone during the day. If they needed to haul water, they would do this before 6 a.m. in a 5-gallon water bag with shoulder straps. The only reasons a lookout was allowed to leave his post were a bad toothache or a death in the family. Lookouts received $70 a month in 1930 and were on the point 24 hours a day between June 15 and September 15. They reported to the smokechaser or ranger station three times a day. A packer would bring mail and supplies just once or twice a summer. The days could quickly become routine in a slow fire season. A typical diary entry of a lookout on the Flathead is as follows: "Saw a bear this morning. Washed clothes this afternoon" (Taylor 1986; Taylor 1981; USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:2).

The life of a lookout was lonely at best. With good communication by phone, many dispatchers opened the lines at night so that the lookouts could talk to each other with their phones hung around their necks. On the Big River Ranger District (the Middle Fork), playing checkers over the phone was a favorite evening pastime among lookouts. In the North Fork, men would sing or play music over the open line (harmonicas were popular, even a trumpet); one man was an excellent yodeler. In the Star Meadow area, half a dozen lookouts would have "bull sessions" together over the phone lines in the evenings (Howard 1939:7; Yenne 1983:30; Anne Clark, "It's Lonely at the Top," Daily Inter Lake, n.d., FNF CR; Taylor 1986).

John Frohlicher, who worked as a smokechaser five summers on the Flathead National Forest in the early 1920s, advised his brother Steven, a new lookout on the Spotted Bear Ranger District:

take time to fix a comfortable camp. Bear grass cut and dried makes a fine bed; it won't take much ingenuity to contrive an icebox in your spring hole to keep butter in; and build a good chair. Better build two, so you'll have one to sit in when the ranger comes to see you (Frohlicher 1929:9).

The first firefinder was a compass. The alidade was soon developed, an improvement because it gave a longer sight axis. The alidade would be mounted over a map board, allowing the lookout to give relatively accurate readings of the direction of a fire to the dispatcher. The mapboard and firefinder evolved through the Koch Board and the Bosworth Firefinder to the Osborne Firefinder (see Figure 73). All these firefinders allowed one to determine the direction of a fire, not the distance to the fire or its location. Dispatchers could pin down the location of a fire if several lookouts observed the same smoke; the intersection of the lines from each lookout drawn on a map would mark the location (Taylor 1986).

|

| Figure 73. Assistant supervisor C. J. Hash taking a reading on Salmon lookout, 1926 (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

Lookouts sometimes confused fog, reflections from ponds, etc., with smoke from fires. In 1941, for example, the lookout on Puzzle Mountain thought he saw a fire and traveled 9 miles to the site. Instead, he found a sheepherder's camp with a Kimmel stove, and about 3,000 sheep in the meadow (Kresek 1984:362).

Until about 1930 many lookouts were manned by two men: a lookout who spotted the smoke and a smokechaser who hiked to the fire and put it out. After 1930 on the Flathead National Forest men were generally stationed alone on a lookout. They would report the fire, go to the fire to begin suppression efforts, and return to their station only after help had arrived (Anne Clark, "It's Lonely at the Top," Daily Inter Lake, n.d., FNF CR).

A smokechaser's "rag camp" included a 10' x 12' tent, a Kimmel stove, quilted bedding known as a sougan, and food. They would use a phone to talk with the lookout and would wait for calls reporting fire. Until the early 1930s, lookouts did not have lightning rods. The men were supposed to go out in a tent during a lightning storm so the Forest Service would not be liable for them, while watching for lightning strikes at the same time. These tent camps did not provide much shelter from storms. Nevertheless, those staying in tents had to pay $5 a month for quarters (Magone 1970; Anne Clark, "It's Lonely at the Top," Daily Inter Lake n.d., FNF CR; Howard 1984).

Smokechasers were on call, night or day, ready to leave within five minutes of receiving a report of a fire. The smokechaser was responsible for Class A fires, those under 1/4 acre in size. He was required to stay out three days; if a lookout called back ten minutes later to say it was a false alarm, there was no way to prevent the smokechaser from a three-day search. After 1940 smokechasers were no longer sent out alone to fires because of safety concerns. Sometimes it could be quite difficult to find a fire on the ground. At least one ranger station on the Flathead kept some old-timers around, trappers who "knew the area like a book," to lead young men to a fire. When the smokechaser found the fire, he noted the time, put his fire pack in a safe place, and knocked down the flames with dirt and cut the limbs hanging into the fire area. Eventually, it successful, he would encircle the fire with a fire line. Then he "mopped up," crawling on his hands and knees feeling the ground for hot spots and checking the area for spot fires. When the smokechaser had finished mopping up, according to Pat Taylor, the ground looked like a "cultivated garden." He then made out his report, watched for smokes until 4 p.m. to make sure the fire was out, and then blazed a line to the nearest trail (Taylor 1986; Helseth 1981; Magone 1970).

The smokechaser's 35-pound pack in the 1920s contained a compass, map, pulaski, shovel, file, whetstone, and three days' emergency rations. The rations were packed in cloth bags and typically contained hardtack left over from World War I, a can of bacon, a can of cheese, rice, a can of milk, oatmeal, and coffee. After World War II smokechasers ate Army K rations. There was no bedding because the men were supposed to keep working until the fire was out. Smokechasers cooked their food on their shovel blade. They made a palouser to use for working at night (this was a lard bucket with a candle and a wire handle that cast a light about 8') (Magone 1970; Taylor 1981; Taylor 1986).

Flathead National Forest lookout Steven Frohlicher was the lookout on Bruce Ridge in 1930. Charles Hash, assistant forest supervisor, spent the night in Frohlicher's tent on an inspection trip. The rattling of the canvas fly and the squealing of the ropes in the wind kept Hash awake. In the morning, "He came out of bed swearing, and he could make a mule-skinner turn green with envy: Any God-damned outfit that would ask a man to live and work in places like this! I'm gonna raise Hell until we get some cabins on these peaks!" Soon a ready-cut lookout from Columbia Falls was delivered to the lookout point by mules. This was the first Superior Building Company lookout on the Forest (Frohlicher 1986:78-81).

Many of the lookouts did not have #9 wire phone lines. Instead, outpost wire was strung to them in the spring and picked up in the fall. When Roy Davis arrived at Tuchuck Mountain in 1930, the first season it was used as a lookout, the trail crew had built a phone line to the point but there were no other improvements. Davis built a map and alidade stand, then hooked up the portable telephone. He next cut and hauled up a ridge pole and tent supports. Later that summer pre-cut lumber for a lookout building and blueprints arrived, and two men came up to build it. Davis spent one night in the new lookout building before heading down the mountain at the end of the season (Howard 1984; Davis 1980).

Obtaining water for drinking and washing was always a concern on a lookout, which was usually a fair distance from a water source. Some of the water sources, a spring or an intermittent creek, were a couple of miles down the mountain. Melted snow was often used for wash water to save hauling the water on one's back. At Spotted Bear Lookout, the closest water was at the ranger station several thousand feet below. The lookout would fill a snow tank with snow in the spring and once again before the snow drifts melted. The meltwater was used for washing windows, scrubbing floors, and bathing. The packer brought up drinking water in four 10-gallon cans in the spring and replaced them a couple of times a season (Funk 1981).

Sanitation on a lookout was sometimes not all that could be desired. At Jumbo Lookout in 1956, for example, garbage was dumped over the cliff to the west of the lookout. The Forest Service inspector recommended discontinuing this practice "since some dudes visit the point. Surely we can set a better example than this even though the point is solid rock" (24PW1003, FNF CR).

During World War II the Flathead National Forest, like others around the country, hired women to work on a few lookouts because of the shortage of men during the war. The Flathead had four lookouts occupied by women then: Nine Mile, Mission, Crane Mountain, and Jim Creek. The Forest Service had hired women earlier as lookouts, at least by the 1920s, but there was resistance because much of the heavier work fell on the rangers, such as phone line maintenance, clearing trail, repairing buildings, and fire fighting (Walter Kasberg to Regional Forester, 2 February 1967, 5100 Fire Management - Historical - Women Lookouts, RO; "Last Women" 1926:701-702).

As of the mid-1960s, no one working inside a Flathead National Forest lookout had been injured by lightning, but a phone line worker was struck and killed by lightning in 1937. In 1929, a fire that started just east of Thompson-Seton lookout reportedly burned the lookout building there. The Review Mountain camp, also in the North Fork, burned that same year, and Huckleberry Mountain Lookout in Glacier National Park burned in both 1929 and 1967. In the 1950s, most of the lookouts built in the 1930s (which had been built to last 15 to 20 years) were in need of replacement or repair (Shaw 1967:96; Yenne 1983:30-32; Kresek 1984:357; Ralph Hand, "History of Region 1 Lookout System," 8/23/54, 5100-Lookouts - Historical, RO).

Beginning in 1945 parts of the Flathead, Lolo, Lewis & Clark, and Helena National Forests greatly reduced the number of manned lookouts in favor of regular air patrols. Between 1945 and 1956 the number of lookouts in Region One were reduced from 800 to 200. From 147 lookouts on the Flathead National Forest in 1939, in 1954 the Flathead National Forest only had 40 positions. In 1966, only 21 lookouts were occupied on the Flathead National Forest during the fire season. These were McCaffery, Mission, Cooney, Jim Creek, Elbow, Desert, Baptiste, Firefighter, Spotted Bear, Bungalow, Red Plume, Mud Lake, Jumbo, Kah Mountain, Pioneer, Nine Mile, Cyclone, Thoma, Johnson, Ashley, and Whitefish. By the early 1990s, fewer than 5 lookouts were regularly occupied (3 October 1956, 1380 Reports - Historical - Reports to the Chief, RO; Ralph Hand, "History of Region 1 Lookout System," 8/23/54, 5100-Lookouts - Historical, RO; Walter Kasberg to Regional Forester, 2 February 1967, 5100 Fire Management - Historical - Women Lookouts, RO).

Aerial photography was initiated in Region One in 1925, and it provided the first reliable maps for many areas of the Flathead National Forest, such as the upper South Fork where the cost of mapping by other methods had been prohibitive. Even in the early 1930s, the maps of many areas were inaccurate (trails were shown on maps as much as one mile from their actual locations, for example). Another mapping project that helped with fire control was fuel-type mapping, which began in 1933. These maps helped determine the number of men to send to a fire in a particular area. The Region-wide project statistically analyzed over 12,000 fires in the 1920s and determined the appropriate level of response for each type of fuel in the region (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:25-26; Taylor 1981; "History of the Use of Aircrafts", n.d., FNF CR:3; Taylor 1986; Caywood et al. 1991:57).

The first air patrols in Region One occurred in 1925 out of Spokane. The planes flew when lookout visibility was low and during lightning storms, and they also did scouting flights on large fires. Until 1927 the Forest Service used military planes and pilots, but after that the agency contracted with commercial air services for fire patrols. The Flathead National Forest began marking its lookout points in 1929 so that they could be more readily located and identified from the air (Gray 1982:24-25).

The first use of air patrol on the Flathead National Forest was in 1929 (a message to "save Spotted Bear Ranger Station at any cost" was dropped from the plane to the fire control staff officer below). In 1930, construction began on seven backcountry landing fields in Montana and northern Idaho. The airfield at Big Prairie was one of the two first airstrips, completed by the 1931 fire season. Four airplane landing fields were being maintained in 1941 to administer the Bob Marshall Wilderness in the interest of fire control; they were not open to the public. In 1946 an aerial patrol plane was stationed at Spotted Bear Ranger Station (Baker et al. 1993:74; Shaw 1967: 134; Caywood et al. 1991:39; Gaffney 1941:429).

The Continental Unit, created in 1945, was the first experimental aerial forest fire control area in the world. It was set up on 2 million acres of roadless wilderness, including part of the Flathead National Forest. The network relied on fire detection from airplanes and fire suppression by smokejumpers primarily instead of ground crews. The Continental Unit radio network included Monture Ranger Station, North Fork Cabin, Fall Pint Lookout, Basin Creek Station, Sentinel Lookout, Big Prairie Ranger Station, Kidd Mountain, Salmon Forks, Brushey Park, Bungalow Lookout, Pentagon Cabin, Schafer Ranger Station, Grizzly Park, West Fork Cabin, Gates Park, Pretty Prairie, Prairie Point, Prairie Reef, Benchmark Station, and Lincoln Ranger Station. The network operated for three experimental seasons, and then the responsibility for fire control was returned to each of the Forests. Based on the experiment, several national forests then put in a system of combined air-ground detection and suppression, and other agencies, states, and Canada later modified the system to meet their needs (24FH431, FNF CR; Clepper 1971:183).

By 1951, over 80% of the fires on the national forests were reported within 30 minutes after discovery. The Flathead National Forest had a greater average distance of fires from roads than the average for the Region. Between 1931 and 1945 the average fire on the Flathead was just over 4 miles from a road. Almost 16% of the lightning fires on the Forest were over 8 hours' travel time from a road (Barrows 1951:174, 187, 195-196).

In 1940, one key smokechaser was selected from each of seven Forests in Region One to participate in the Forest Service's experimental smokejumper program (Dick Lynch was the Flathead representative). In 1941 the smokejumpers were based at Nine Mile near Missoula, Big Prairie on the Flathead, and Moose Creek on the Nez Perce. In that year there were three squads totalling 26 men. In 1942 there were four squads, one of which was stationed again at Big Prairie. From 1943 until the end of the war the smokejumper program was kept going by volunteers from the Civilian Public Service program (conscientious objectors), and a crew of these men was stationed at Big Prairie during the war. Johnson Flying Service of Missoula was contracted to fly jumpers in Region One. The company purchased its first Ford Tri-Motor plane in 1935, which by then had become obsolete for commercial use. The last Tri-Motor had been built in 1933, but they were used over 30 years by Johnson and were a familiar sight in the skies over the Flathead National Forest during fire season. The first smokejumpers (13 in number) to jump on a Flathead National Forest fire were dropped into the Dean Creek drainage in 1941 (Cohen 1983:13, 26-27, 30, 38, 42, 64, 68-69; Baker et al. 1993:163; "History of Smokejumping," 1959, FNF CR: 1-8; Shaw 1967:134).

By 1944 smokejumping was standard practice, no longer experimental in Region One. In 1945 there were about 235 smokejumpers in the program, and some national forests had reduced their ground forces to depend more on smokejumpers. The fire season of 1945 demonstrated that smokejumpers combined with air detection could save money ("History of Smokejumping," 1959, FNF CR:9).

Smokejumpers experienced tragedy in fires, as did ground crews. In 1949 the Mann Gulch Fire on the Helena National Forest killed 12 smokejumpers and a district guard. Two of the smokejumpers who died in the fire were from Kalispell; one was the son of long-time Flathead National Forest employee Henry Thol.

Fire Suppression

As discussed above, early efforts at fire control on the forest reserves were severely limited by lack of money, transportation, and communication systems. One of the earliest descriptions of fire suppression on the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve was written by forest supervisor Gust Moser. Moser and about five men built 26 miles of fire line, a tremendous accomplishment. Moser reported, "with the limited force I have had, better results have never been attained in fighting forest fires....Am satisfied that our work has saved enough timber to pay the full expense of running the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve for the next 10 years. We were entirely out of provisions for three days, all we had was bread and venison, I had a lot of provisions 25 miles up the river but did not have a man to spare to send after it" (16 August 1900, entry 44, box 4, RG 95, FRC).

The "genius" of early fire protection lay in the organizational skills of the Forest Service, including the standardizing and coordinating of tools. The Forest Service developed special tools for fire control beginning about 1910. Innovations included the Osborne firefinder (ca. 1910), the brush hook, the smokechaser pack frame or "Clack board" (developed by Jack Clack, who had worked on the Flathead National Forest), the Koch tool (a combination shovel and hoe developed by Elers Koch of the Regional Office in Missoula), the portable water pump, special rakes, and the Pulaski (a combination ax and mattock developed by Ed Pulaski after the 1910 fires) (see Figure 74). The development of a sleeping bag with shoulder straps, filled with kapok fibers, was a significant innovation. The 9-pound bag replaced the 23-pound bag used previously, allowing three pack horses to be eliminated from a pack string moving a 25-man outfit. Bill Nagel, supervisor of the Blackfeet National Forest, owned the first sleeping bag used in the area in the early 1930s. Within a few years "kapoks" were in fire caches and then in general use on the Blackfeet and Flathead National Forests (Pyne 1982:425-526, 429-430, 432; Bradeen 1931:5; Taylor 1981).

|

| Figure 74. Portable water pump in use on Wolf Creek fire, 1924 (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

Pat Taylor described the on-the-ground men working for the Forest Service in the 1930s as dedicated and hard-working. "I saw men work on fires in those times until they would be so exhausted they would just fall over and lay there in the fire trench trying to get their breath...They got 35 cents an hour and their board, if they could find anything to eat around the fire camp" (see Figure 75) (Taylor 1981).

|

| Figure 75. Putting final touches on fire line, Tango Creek fire, 1953 (photo by W. E. Steuerwald, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

Other Forest Service workers had different experiences. As John F. Preston commented after his experience with large fire crews on the Big River (Middle Fork) fires in 1914:

Some cripples are sent who it is perfectly apparent can not be of much service. A one armed man, and an old fellow who was so stiff he could hardly walk, were sent to the Vinegar fire (John F. Preston, Report on Big River Fires, 1914, 1914 Fires Flathead, RO:2/7).

Other supervisors complained that some fire crews felt that if they got a fire under control they would lose their job. Foremen often preferred to hire local men who were personally interested in stopping the fire because it was burning near their own homes or because they had other work to get to (27 September 1919, 5100-Fire Management - 1919 Fire Season - General, RO).

In the 1929 season, approximately 241,000 acres burned (67 of the fires were on the Flathead National Forest, including the Half Moon fire that burned over 100,000 acres). Some of the large fires in 1929 burned in the Java area and on the South Fork near Spotted Bear Ranger Station (Baker et al. 1993:150; Whitefish Independent, 16 August 1929).

The Half Moon fire of 1929 that burned east from Columbia Falls to Lake McDonald tested the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests' ability to fight large, fast-moving fires. The fire burned 103,400 acres (29,400 on Forest Service land) (see Figure 76). Slash, brush, and downed timber from a 1924 windstorm fueled the flames, and the fire destroyed buildings, ranches, privately owned timber, and logs and ties piled in decks. Thirty men at a logging camp north of Columbia Falls were trapped by fire but later rescued. One man escaped death near today's Blankenship Road by lying in an irrigation ditch ("Appraisal" 1930; Whitefish Independent, 23 August 1929).

|

| Figure 76. Half Moon fire burning over Teakettle Mountain near Columbia Falls, 1929 (photo by K. D. Swan, courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

The fire traveled more than 30 miles in runs on two successive days, and it crossed three mountain ranges and the Flathead River. It took about 1,000 men a week plus nearly 100 miles of fire line to bring the fire under control (see Figure 77). A total of 5,208 man days were spent on the fire. Help was provided the two national forests by the Northern Montana Forestry Association, the State Lumber Company, and the J. Neils Lumber Company. Forest officers were flown in from as far away as Arizona and New Mexico to work on the management team (box 16, folder 1, "Number of Men Employed," NMFA Papers, UM; USDA FS "Early Days" 1955:38).

Area burned:

Glacier National Park 50,000 acres Blackfeet National Forest 1,700 Flathead National Forest 27,700 non-federal land 24,000 total 103,400 Suppression costs (estimated):

Glacier National Park $119,162 other agencies 75,000 total cost $194,162

| Figure 77. Half Moon fire of 1929, acres burned and fire suppression costs ("Appraisal" 1930). |

The Half Moon fire was started by sparks from a logging railroad locomotive. In order to sue the lumber company for damages, it was necessary to cruise the burned area. This was done on snowshoes in the spring of 1930. According to one participant, 25 men from Region One were detailed to help with the cruising. He said, "The Park personnel claimed they knew nothing about cruising and as a result they sat around nice warm fires while Forest Service employees tackled the job." In 1932 the government apparently filed a suit against the State Lumber Company for property damage and the cost of suppression, but the result of the case is not known (USDA FS "Early Days" 1976:206; "Half Moon" 1932:12).

The Half Moon Fire burned on J. Neils land north of Columbia Falls. At that time Neils was logging in the Coram area. The company had 345,000 cedar poles at the logging site and no fire insurance. Although the logging camp and a Shay Locomotive burned, the cedar yard was saved. The company then salvaged the valuable burned white pine and spruce. They had two railroad logging camps operating within three weeks, with tractors and about 200 men from Libby, and they shipped up to 40 cars of logs a day. By next spring much of the spruce was not merchantable, but the white pine was good through 1930. The Douglas-fir and western larch were not salvaged because there were not enough tie mills available to harvest the timber both in the Columbia Falls area and along the Flathead River (P. Neils 1971:59-60).

During World War II the Forest Service experienced a drain of experienced personnel to military service and the war industries, and the CCC program ended. Various programs, such as the Forest Fire Fighters Service and the Civilian Air Patrol, helped provide personnel, and a special fund was established to employ and train standby firefighting crews towards the end of the war. Students (16- and 17-year-olds) were recruited for firefighting and to work on slash disposal. Shortly after World War II, Region One, in cooperation with Fire Control, designed and put together the disposable mess gear that was soon generally used and accepted by all western regions and stocked at the Spokane warehouse (W. Robbins 1982:162-163; Baker et al. 1993:160; 3 October 1956, 1380 Reports - Historical - Reports to the Chief, RO).

Airplanes allowed for a variety of new fire-suppression techniques. The first fire camp was dropped in on Bunker Creek in 1939. In 1947 water bombs were dropped on a fire on the Deerlodge, and the use of chemical fire retardants followed in 1958 on the Flathead. Helicopters were first used in the Flathead National Forest in 1957, for fire control and administrative use (Shaw 1967:9, 134).

By 1935 fire control officers in Region One were prepared to implement the new Forest Service "10 a.m. policy," which was to aim to control every fire that was detected by at least 10 a.m. of the following day. This policy standardized firefighting for the first time, and it was not superseded by a wholly new policy until 1978. Continuing alarm over the phenomenon of mass fire encouraged the support of the tough 10 a.m. policy that guided Forest Service suppression tactics. A 1934 fire on the Selway led to a major debate over the virtue of fighting every fire, but the previous policy of suppressing all fires won out. At that time the Forest Service also began allocating presuppression budgets as determined by fire danger (Pyne 1982:176, 282-83, 290; Hardy 1983:22).

As early as the summer of 1910, men in the California lumber industry were arguing the benefits of light burning (prescribed burns to reduce fuel and thus fire hazard), and the Forest Service did study the issue. After the 1910 fires in Montana and Idaho, however, the Forest Service could not even consider the thought of intentionally setting fires. It was not until Lyle Watts, the last of those who had been through the 1910 fires, succeeded Earl Clapp as Chief Forester in 1943 that the Forest Service approved the concept of light burning (Pyne 1982:251; Steen 1976:135-36).

Cooperative Fire Efforts

Fires started along railroad tracks have always been a major concern in the northern Rockies, and various laws have tried to reduce the chance of such fires getting started. An 1881 Montana act required railroads to keep their right-of-ways clear of all combustible material on each side of the track for the whole width of land owned by the railroad up to a distance of 100'. In 1901 the law required plowing a 6' firebreak on both sides of the track, but it did not apply to mountain districts or routes next to cultivated fields. Beginning in 1907, monetary damages could be collected for any actual loss resulting from a railroad fire. The development of a practical centrifugal spark arrester for railroad locomotives in 1930 was an important technological innovation in fire prevention (Kinney 1917:28; Moon 1991:21-22, 96; Headley 1932:184).

Railroad companies often contributed men to fight fires along their lines. For example, on a 1900 fire started by a railroad locomotive, the Great Northern Railway sent 70 men to fight the fire at no charge to the government (July 1904 fire report, entry 44, box 4, RG 95, FRC).

In 1919 the first state slash law was passed requiring all logging debris to be burned within a year to reduce the fire hazard. In that year the state also regulated railroad exhaust systems, skidders, loaders, locomotives, and portable engines for the first time (Moon 1991:62).

In 1887 the Territory of Montana passed a law making the careless or intentional starting of a forest fire punishable by fine or imprisonment. For example, a Belton man was convicted of leaving a brush-burning fire unattended which spread to Flathead National Forest land. He was convicted and fined $100 plus costs. The government also won a suit against the Great Northern Railway in 1917 over fire damage to the Flathead National Forest and Glacier National Park which started on the railroad right-of-way. In 1939 the state legislature required all private owners of land classified as forest land to be assessed for forest fire protection ("Government" 1920:4; Moon 1991:8, 99).

The Montana state board of forestry was established in 1909, and its duties included fire protection on state lands. Federal forest rangers were to serve as state fire wardens on state land. The new state forester began working out cooperative programs with the Forest Service for fire protection. In 1911 the Montana State Forester designated volunteer firewardens for the first time (Moon 1991:44; Little 1968:18-19). The Weeks Law of 1911 greatly helped cooperative fire protection by providing funds for the Forest Service to patrol state land.

In 1908 the first national conference on the conservation of natural resources was held at the White House. One result of the belief in an imminent timber famine was that greater attention was given to fire detection and control, especially by states. Private timber-protection organizations formed first in the northwestern part of the country because of the need to organize men and facilities to act quickly. In most states outside of the northern Rockies, the Forest Service, private landowners, and the states had separate firefighting organizations that normally did not work together. In northern Idaho, protective associations were organized by 1906, and other associations were organized in Montana, Oregon, and Washington (Clepper 1971:29, 45, 48; Winters 1950:33; Baker et al. 1993:301).

One of the positive responses to the 1910 fires was the formation of a cooperative association in Montana to help with fire protection. The Northern Montana Forestry Association (NMFA) was organized in 1911 by a group of forest landowners in order to provide forest fire protection as a group. The main office was located in Kalispell; the chief fire warden for many years was A. E. Boorman. The initial levy was 1/2 cent per acre owned, and the money was used for organizing and equipping fire patrolmen and fire suppression crews. Over the years the organization also began protecting private forest lands from loss by disease and other causes. The organization was very active in the area until approximately 1935. Then its importance declined as firefighting techniques and equipment became more costly, as depression-era timber income dropped, and as the Forest Service got more money and help from the CCC. The NMFA operated until 1969, when the Montana state forestry department took over the fire control duties of the association (Moon 1991:44-45; NMFA Papers, UMA; Baker et al. 1993:303).

By 1920 the NMFA had 910,000 acres under its jurisdiction, and it was the only association of private owners in Montana. At that time, most of the Weeks Law funds were paying for the Forest Service to patrol state land. In 1921 the Blackfoot Forest Protective Association formed. In 1927 a Montana law required every landowner to be responsible for the control of fires burning on his land, so large numbers joined the two associations ("Co-operative Fire Protection in Montana," 3000 State and Private Forestry - General Corr, RO).

By 1929 the NMFA boundaries included approximately 2,250,000 acres of federal, state and private lands, 90% of which were listed with the association. The NMFA also built its own lookouts. For example, they built the original lookout on Haskill Mountain in 1926 and replaced it in the late 1950s, later giving it to the state. The assessment charged landowners at that time was 2 cents per acre. The various national forests reimbursed the NMFA the cost of suppressing fires within Forest boundaries. The Forest Service helped solicit new members to the association, saying that the agency would like to have all standing timber and young growth on land that would not be in demand for agriculture well protected against fire. In some years the Forest Service and the NMFA did not work together because of disagreements over rates per acre (October 1929 letter, box 5, folder 19, NMFA Papers, UM; 30 March 1926, folder 17, box 9, NMFA Papers, UM; "20th Annual Report of the NMFA, 1930," box 35, folder 3, NMFA Papers, UM:4).

According to one Flathead National Forest employee, the NMFA was quite cooperative with the Forest Service, although there was some grumbling that the association did not act efficiently on fires if no merchantable timber was involved. Much Forest Service land was actually given over to them to protect. If a fire was located near a national forest boundary, the Forest Service would send crews in, but if it was inside the NMFA boundaries the Forest Service would report it and the NMFA would send in its own crews (Helseth 1981;7 February 1924, Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC).

The Clarke-McNary Act of 1924 made federal matching funds available to qualified state protection agencies for fire control, reforestation, and other purposes. In 1926 the state of Montana was still paying the Forest Service to protect the Stillwater State Forest from fire. After the Stryker fire and another by Keith Mountain blew up (with state workers claiming that the Forest Service had not fought the fires hard enough), the state decided to get into firefighting itself, and in 1928 the state became solely responsible for fires on its land (Steen 1976:190; Moon 1991:69; Cusick 1986:10).

The state built its first permanent lookout in 1914 on Werner Peak, a log cabin with a glass cupola on top. That year, Montana had 282 fire patrolmen walking and riding the woods, each man covering an average of 63,000 acres. Most of the patrolmen worked for the federal government, but some were employed by the state, the Northern Pacific Railroad, J. Neils Lumber Company, ACM, Bonner's Ferry Lumber Company, and the NMFA (Moon 1991:60-61).

In 1956 the State Board of Forestry approved the formation of the Swan River State Fire Protection District. The state forestry department then began providing fire protection on the state, federal, and private lands within the district, and the buildings at Goat Creek in the Swan Valley were constructed in the next few years (Conrad 1964:32).

Some lumber companies, such as the F. H. Stoltze Land Company and the ACM, cooperated with the Flathead National Forest by donating land for lookout sites. The City of Whitefish also cooperated with the Forest Service by paying the salary of a Forest Service lookout on Whitefish Lookout (FNF Lands; 26 November 1937 memo, Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC).

The Flathead Indian Reservation had no established fire lookouts until 1931, but their forestry officials communicated by phone with six Forest Service lookouts near them. They also provided men to fight fires under cooperative agreements with the Forest Service, the state, and private forestry associations (Historical Research Associates 1977:241-242).

The Forest Service assisted on the 1910 fires in Glacier National Park and on other fires in the Park, including the large 1936 Heavens Peak fire. In 1923 the Park agreed to build a lookout on Elk Mountain that would chiefly be of help to the Flathead National Forest, and in return the Forest agreed to build one on Nyack Mountain to help the Park. In 1923, the Park developed lookouts near Bowman Lake and on Huckleberry Mountain in return for detection from Forest Service lookouts. The Forest Service selected, trained, supervised, and inspected these positions. By 1923 the two agencies had a direct phone line to aid in cooperative fire detection and suppression efforts (Shaw 1967:91; 15 December 1923 and 7 February 1924, 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC; Schene 1990:69-70).

Even in the early (GLO) years, the Forest Service was actively trying to educate the public about preventable fires, if only by posting the national forests with fire warnings and notices to campers. After the 1910 fires, the publicity campaign increased until notices were provided in phone directories, railroad timetables, hotels, and so on (Woolley 1913:763-764).

Smokey Bear was created in 1944 because of concern over the nation's timber supply. The Advertising Council wrote ads and posters to encourage citizens to participate in fire prevention.

The most popular slogan, "Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires," was created in approximately 1947. This and other advertising techniques resulted in a marked decrease in man-caused forest fires (Morrison 1988:3, 7-8, 10).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap9.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |