|

The National Forests of the Northern Region Living Legacy— |

|

Chapter 6

Generation of Change and Progress

The period from 1911 to the beginning of World War II was one of significant changes for the Northern Region. The Forest Service reorganized and consolidated the national forest entities. The lumber industry in the Region experienced a boom period, followed by a collapse during the Great Depression. The introduction of the Civilian Conservation Corps into the forests and grazing lands of the Region brought, for the first time, adequate labor to improve the valuable pine stands, cope with timber diseases, and fight the almost annually recurring forest fires.

Central to the planning and direction of these changes was the leadership contributed by the men who served as regional foresters for Region 1 during these years. They were Ferdinand A. Silcox, Richard H. Rutledge, Fred Morrell, and Evan W. Kelley. Each in turn left his personal stamp on Region 1.

The Silcox Years

Silcox became Regional Forester in 1911 when William Greeley left for the Washington Office. By this date, Silcox (or Gus or Sil as he was usually called by his friends) was already, at age 29, destined for greater honors and larger responsibilities. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, his grandfather had been a Confederate blockade runner during the Civil War. An honor student, he excelled at Charleston College and then at Yale, where he earned a master's degree in forestry in 1905. He attracted the personal attention of both Dean Henry S. Graves and Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot, who found him resourceful, courageous, endowed with both knowledge and common sense, and capable of inspiring confidence among his colleagues—a rare combination. In the summer of his junior year (1904), he cruised timber in the Hatfield-McCoy feud country of West Virginia, where he settled boundary disputes and impressed all sides with his knowledge, fairness, and athletic abilities. [1]

After graduation, the Forest Service sent him west to manage a new timber reserve and settle disputes between cattle and sheep owners over grazing rights. He surprised all parties by settling the controversy in person and on the ground, not back in his office with a map. It took several days, but when he finished, both sides acknowledged that they had gotten a "fair shake."

Colorado at that time was rife with timber frauds by alleged homesteaders, who filed claims and then planned to sell their 160 acres to a larger lumber company without either living on the claim or improving the property. Silcox would place a dated chunk of wood into the stove of the cabin where the homesteader was supposed to spend the winter, and 2 or 3 years later, the claimant's case collapsed when the ranger opened the stove door and pulled out the same chunk of wood. This ingenuity, energy, and enthusiasm for his work, plus his demonstrated grasp of sound forestry principles, earned Silcox seven promotions in less than 3 years. [2]

As assistant forester of the Northern Region under Greeley, Silcox handled the logistics and supply problems arising from the great 1910 fire. He located and hired thousands, brought tons of supplies and equipment, and arranged to get both fighters and materials to the fire front, which enclosed approximately 26 million acres and stretched about 250 miles north and south and 200 miles east and west. He was commended for "most efficient service" and promoted to regional forester to succeed Greeley.

The Silcox team differed only slightly from those who had worked with Greeley. The headquarters group in 1911 included the following:

| District Forester | F.A. Silcox |

| Assistant District Forester (Operations) | John A. Preston |

| Assistant District Forester (Timber Management) | David T. Mason |

| Assistant District Forester (Lands) | Richard H. Rutledge |

| Assistant District Forester (Grazing) (plus clerical and secretarial personnel.) | C.H. Adams |

Elers Koch was Supervisor of the Lolo National Forest and Charles Fisher, followed by W.B. Willey, directed the Clearwater National Forest. On the Custer and Sioux National Forests, a number of men served as supervisors during the decade, with J.C. Witham the first on the consolidated Custer National Forest.

Silcox believed strongly in decentralization and grassroots control. As he wrote, "Fundamentally, the ranger district is the basic unit of our organization." With competent rangers in charge of their districts and in communication with their public, the Supervisors could more effectively define needs and standards of work, carry out inspections, and determine priorities for the monies available. [3]

The checkerboard pattern of public land surveys and sales resulted in difficult-to-manage land blocks that plagued the State of South Dakota (and other Western States), ranchers, timber companies, and the Forest Service. The best solution for all parties in this situation was usually a mutually acceptable land exchange. Between 1910 and 1912, South Dakota and the Forest Service swapped approximately 60,000 acres of land in the Black Hills for a similar acreage in Harding and Custer Counties. South Dakota incorporated the new lands as Custer State Forest, and the additional forest lands became part of the Custer National Forest. [4]

An immediate problem for Silcox was the vast amount of fire damaged pine left by the 1910 fire, most of which, if handled at once, could be salvaged. He energetically made contacts and arranged sales for approximately 100 million board feet of this timber. To speed the reforestation of the area, he established the Savenac tree nursery. While small at first, the nursery grew and developed until it became the largest in the country. Silcox also rushed the inventory of the region's resources, because intelligent planning could not be pursued until the amount, kind, and age of the timber were determined. He insisted that timber cruising be carried on in every ranger district, on a larger scale than had been done previously, until the entire region was mapped.

Silcox also took action against the widespread land frauds in northern Idaho. The pattern was familiar. Alleged homesteads filed claims to quarter-sections of land—too steep, rough, and completely unsuitable for farming, but heavily forested in white pine. These claims, when patented, could be sold to lumber companies for $10,000 to $25,000. The timber would be cut and the cutover lands abandoned. To Silcox, this action clearly defeated the purpose of the homestead laws and supported his contention that these lands should never have been opened for settlement. He collected data, sent out Forest Service personnel to identify specific persons involved, and wrote a report to Washington calling for action to stop these fraudulent patents.

There also were filings under the Forest Homestead Act of 1906; some applicants sought patents on lands that strategically controlled access to a much larger acreage of Federal lands, thus making these lands a private preserve because they were inaccessible to the public. Silcox and later regional foresters and their staffs sought to prevent such patents. In the summer of 1915, Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston went with Silcox into the Idaho woods, and he found that Silcox's report was accurate. On his return to Washington, Houston canceled a large number of pending claims. With the cooperation of Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane, he arranged to have a person from the Forest Service take part in handling all future claims and patents from would-be homesteaders. [5]

The problems of delineation and administration of the Custer National Forest also required Silcox's attention. Unlike most of the national forests in Region 1, the Custer was scattered, sprawling, disjointed, and made up of many segments, which at one time stretched more than 600 miles. Much of the enclosed lands were not forested; they included grasslands and waste lands. Some politicians and ranchers proposed that these lands be removed from the National Forest System and returned to the General Land Office for private entry.

Consequently, Silcox undertook a study and survey of the entire forest. He recommended to the Chief of the Forest Service that the entire Ashland District, southeast of Billings, be transferred from the national forest and opened for entry. When news of this proposed change was made public, a number of the larger ranchers protested vigorously. They recognized that the Forest Service permit system to regulate the grazing allotments had brought much-needed order and reasonable division of the grazing areas. They feared that with no regulation, the range would soon be overgrazed and all ranchers would suffer. As a result, the Ashland District remained part of the Custer National Forest. However, in 1917, the agency (with Silcox's approval) abolished the more eastern Dakota National Forest through a presidential proclamation. [6]

Forest fires and their control continued to occupy much of Silcox's time. Both 1914 and 1917 were bad fire years, but the disaster of 1910 was not repeated because Silcox had established a central warehouse for emergency tools and supplies. The region standardized equipment units and adapted all loads for transportation by packhorse or mule. Silcox cooperated with State officials and leaders of the timber industry, especially the Western Forestry and Conservation Association. Employees of the large lumber companies would normally be enough manpower to fight forest fires, but in 1914, they were not available. In the Northwest from 1913 to 1919, there were violence, strikes, sabotage, and bitter recriminations between workers and management of both the mining and forest-products industries. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) attempted to organize the workers of both industries but were met by solid opposition from the owners. In 1914, unknown persons destroyed the Union Hall in Butte with dynamite, and in 1917, a lynch mob seized and hanged union leader Frank Little. IWW responded with sabotage, strikes, and a "slowdown" at work.

The list of workers' grievances was long and inclusive: poorly planned camps with bad drainage, overcrowded barracks, lice infested bunks, poor food, a 10-hour workday, low wages (about $2.00 per day was standard), and the requirement of a "Rustling Card" for employment. The "Rustling Card" contained a complete record of the individual, past employment history, the reason for leaving the last job, and a statement that the person was not a member of IWW. Mill and mine owners demanded that the Forest Service deal only with them for firefighters and not with the union or its leaders; however, IWW had control of the workers, who ignored any orders from management.

To break the stalemate during the 1917 emergency, Silcox went directly to IWW headquarters and persuaded the workers that it was in their best interest to fight forest fires, especially on national forest land. He explained that the forests were publicly owned; everyone had a stake in them and their well being. As a result, the union pledged its support and provided the needed personnel to fight the fires that summer. A little later, Silcox was similarly successful in Seattle. [7]

Throughout his tenure as Regional Forester, Silcox was concerned about people, especially the people under his direction in the Forest Service. He pushed for more and better "on-the job" training and opened up promotion possibilities to people who had previously been in "blind alley" jobs. Before he left the region, he had set up a promotion policy by which workers could qualify for better jobs simply by improving themselves, regardless of their earlier background.

The outbreak of World War I had a profound effect on all aspects of the Forest Service, the timber industry, and the States of Montana and Idaho. As relatively new members of the Union, with populations that included large numbers of recent immigrants, both States had numerous settlers (for example, Germans, Scandinavians, and Irish) who were reluctant to participate in the war effort. The existence of this "isolationist" bloc later attracted special attention from the internal security authorities in Washington. As early as March 1917 (after the break in diplomatic relations with Germany but before the declaration of war), Chief Henry S. Graves sent letters to all members of the Forest Service pointing out that they had an important public responsibility with regard to guarding public property, aiding critical industries, and protecting the public welfare. He emphasized that the agency was in a position to render other services to the authorities in Washington regarding information on men of military age, meat and grain supplies, availability of minerals and timber, facilities for transport, and, if needed, patrol functions to protect lives and property in each region. In short, Graves felt that most men of military age could serve their country better by continuing their roles in the Forest Service than by volunteering for the Armed Forces. [8]

The United States entered the war on April 6, 1917. Just 2 days later, Silcox wrote a confidential letter to the forest supervisors in the region. Apparently acting on further instructions from Washington, he called on all forest officers to render service as an intelligence information force. They should report anything affecting the welfare of the Nation, including any possible danger from alien sympathizers. They should not overreact to mere rumors, but if a situation became serious, they should get in touch with local law enforcement officers. They should not attempt to make arrests themselves without further instructions. They also should complete and forward to headquarters the inventory of points that might need protection, such as bridges, trestles, tunnels, or other installations. [9]

The situation, however, changed rapidly after Congress passed the Selective Service Act to send approximately 2 million men abroad. The War Department determined that the expeditionary force would need a forestry regiment for service in France. Chief Graves alerted regional headquarters on May 4, 1917, that the Forest Service would raise such a regiment, led by competent foresters and equipped with portable saw mills and other logging machinery. The regiment must provide the Army with needed timber and lumber, while avoiding waste and leaving the forests, which had been under management by French foresters for a century, in good condition for future production. Among the first foresters chosen was former Regional Forester William B. Greeley, who was commissioned a major. Robert Y. Stuart, who had served under Greeley as head of operations, also accepted a commission and went overseas as a major. Graves also took leave from his duties and served on General Pershing's staff, mapping plans for the forest troops. [10]

Silcox distributed a brochure, "The Forestry Regiment, and How to Join It." The regiment was to consist of six companies of 164 men each, with the pay scale of $61.20 per month for overseas service. Silcox urged single men, not designated as part of the permanent skeleton organization, to join up at once. Every effort would be made to recruit a quota of at least 50 men in the service in the 10th Forestry Engineers. By late July, the regiment assembled in Washington, and in early October, it arrived in France. By this time, General Pershing (on the advice of Major Graves) had determined that additional forestry personnel were needed and ordered the recruitment of the 20th Forestry Engineers. This was to be a much larger organization, including 10 battalions of 750 men each, a total of 7,500 men. Region 1 furnished its full quota of men for the regiments. According to forest historian Roger M. Peterson, 256 men from the Northern Region had applied for enlistment by early November. A month later, that figure had grown to 442. Still more enlisted in 1918. [11]

The war emergency soon brought an end to Silcox's time as head of Region 1. He was ordered to Washington, commissioned a captain, and directed to train the 10th Forestry Engineers for overseas duty. He never did go to France. The Secretary of Labor drafted him to be a "troubleshooter" for the U.S. Shipping Board in labor disputes on the west coast. Consequently, instead of embarking for France, he left for Seattle to again mediate among IWW, the Government, and employers over wages, working conditions, and benefits. He was generally successful, thanks to his earlier experiences at Missoula and Coeur d'Alene. He hammered out a general settlement between management and labor, which included Army standards for housing and food in lumber camps, an 8-hour workday, a 75-cents-per-hour wage, and no "Rustling Card." After the war, Silcox left the Forest Service for a decade. He would return as Chief in 1933 and work under President Franklin D. Roosevelt in fashioning the New Deal for the Forest Service and the forest-products industry. [12]

Region 1 During the War Years

With the departure of Ferdinand Silcox, Assistant Forester (Lands) Richard H. Rutledge became acting forester and later Regional Forester, serving in that capacity until 1920. He recruited additional men for the 20th Forestry Engineers and followed up on calls from the Department of Justice regarding stories of enemy alien activity. He urged personnel to turn into regional headquarters any reports of such activity within their forest areas. Such reports should be accompanied by witnesses' statements and not be overly influenced by rumors. As in other States, Montana and Idaho had a number of cases in which German-Americans were browbeaten and sometimes terrorized because of their pacifist views or simply because of their names. The Forest Service personnel exercised some moderating influence on the excessive zeal of self-appointed vigilantes. [13]

The Region 1 "family" remaining home made efforts to aid the war drive. The men of the skeleton force collected funds to purchase an ambulance that would accompany the 10th Forestry Engineers to France. When the initial contributions fell short, the workers agreed to payroll deductions until the goal was reached. By late February 1918, the women of the region had knitted 99 sweaters, 115 pairs of socks, and 31 wristlets, which were forwarded to Washington for the men in service. As in other parts of the United States, families in Region 1 observed meatless, wheatless, and sugarless days for the duration of the war. [14]

Not all of the foresters' time was spent organizing the war effort, fighting forest fires, or apprehending forest thieves. Most of the days and months were routine. Forest Service personnel cruised timber, arranged sales to lumber companies, issued grazing permits, collected fees, and patrolled their assigned areas of the region. There also was time to become acquainted with the local farmers and ranchers, assist in a variety of tasks, and participate in social gatherings. K.D. Swan recalled that he and Ranger Ralph Sheriff hosted a community dance one summer at the ranger station located on a tributary of the Little Missouri River:

Late in the afternoon Sheriff and I hitched up the team and drove to a ranch ten or twelve miles away where we picked up a small organ which was always available for affairs of this nature. Guests from all directions began to arrive at the station about dark. Some were on horseback, some rode in buggies or wagons. It was before the days of baby sitters. All the babies and children came with their parents.

Stout hands moved the stove out into the yard and put the other furnishings on the porch. The organ was moved in and a chair was placed for a fiddler who showed up from somewhere. Children were eventually put to bed on the cots out on the porch or in the wagon boxes. Riding stock was unsaddled and tied about the yard or turned into the corral out by the barn. Teams were unhitched and given hay to munch during the long wait. The moon was nearly full, making it almost as light outside as it was inside the station. The crowded room would not accommodate all the dancers at one time which made for a lot of social activity in the yard where little groups stood around and discussed the coming presidential election, the hay crop, and neighborhood matters in general. Just after midnight, lunch was served by the women. Coffee was made on the stove to which a couple of lengths of stovepipe had been attached. I remember well the picture made by the sparks and billows of black smoke from fat pine surging upward in the moonlight. All in all, it was a night one could not easily forget.

As dawn reddened the east, some of the women got breakfast, frying bacon, eggs and potatoes which, with bread and coffee, would fortify the men and boys who had to return to a day's work in the hayfields. And so they rode away, this group of friendly people, each feeling I am sure, a little happier and thankful for this social contact with good neighbors. [15]

There was often time to hunt, check on game, and explore the rugged mountains and canyons that made up much of Region 1. One of the favorite areas was the Beartooth range on the Custer National Forest, just north of Yellowstone National Park. There, the ranger would find moose, elk, deer, bears, bighorn sheep, mountain lions, wolves, and coyotes. During the summer of 1920, Forest Service personnel joined ranchers on the eastern part of the Custer in a big wolf hunt. The ranchers claimed that wolves had become a serious menace to the livestock industry and aimed to eliminate these predators entirely from this section of the range. Only slowly did Forest Service personnel and ranchers come to understand and accept the inherent interdependence of all life in maintaining an ecological balance. Such a doctrine of a "land ethic" was later articulated and popularized by Aldo Leopold in his writings, but many early foresters contributed to the concept.

Many foresters enjoyed climbing and exploring Grasshopper Glacier. There, millions of locusts had been entombed in the ice at the 11,000-foot elevation. When the glacier receded in the early 20th century, the insects were exposed to the air causing the area to reek on warm days. Just when these insects were frozen is a question for discussion. Some geologists assign a date as recent as the 18th century, but others say it was thousands of years ago. There were other glaciers "Castle Rock, Thunder Mountain, and Windy Gap" that could be climbed, and each demonstrated the progression and recession of the glacier as the weather cycles changed. The accumulated rocks and boulders beyond the current edge of the glacier ice have prompted questions and often humorous retorts from the ranger. The following was typical:

Tourist: Where did all these big rocks come from?

Ranger: The glacier brought them down.

Tourist: Where is the glacier now?

Ranger: Gone back for more rocks. [16]

A more formidable challenge was Granite Peak. This imposing mountain is the highest land mass (12,799 feet) in Region 1.

Rangers and mountaineers had made repeated attempts to scale the peak, but the difficult surrounding country and its sheer sides defeated all efforts until after World War I. Elers Koch, former Supervisor of the Lolo National Forest and in 1923 Assistant Regional Forester (Timber Management), was an avid mountain climber and for years had a special interest in climbing Granite Peak.

During the summer of 1923, he gathered a party of climbers, including Forest Service veterans J.C. Witham and R.T. Ferguson, to make a concentrated assault on the last "virgin peak" in the region. They were joined by another group of climbers, and they made their way together to about the 10,000-foot level. Koch, Witham, and Ferguson chose the eastern ridge and successfully reached the summit on the morning of August 30. The others in the party chose the southwestern face but were forced to turn back a few hundred feet below the summit. It was a triumphant and exhilarating feeling for the three friends as they planted a staff and an American flag on the top of the granite mass. Although the peak has been climbed many times since, it is still regarded as a major challenge to any mountaineer. Koch recalled it as one of his most satisfying achievements. [17]

|

| Granite Peak - highest mass in Region 1 (12,799 feet). |

Rutledge continued to serve as Regional Forester until 1920. A difficult period of readjustment followed the end of the war. Rutledge was an expert on range and grazing and strongly pushed the concept that grazing fees should be increased to a realistic level and grazing use should be limited to preserve the range. He also was a careful administrator and systematic planner, unafraid to support his beliefs in the face of opposition. In 1920, he transferred to the Intermountain Region in Ogden, Utah, where he labored for almost two decades to develop a sound range policy. In 1939, Rutledge moved to the Washington Office of the Department of the Interior, where he became Secretary Harold Ickes' spokesperson on public land use. He engaged in a series of well-publicized confrontations with western congressmen and senators and their rancher friends. He retired from public life in 1944. [18]

Fred Morrell

Fred W. Morrell succeeded Rutledge. Born in Nebraska in 1880, Morrell attended the University of Nebraska and Iowa State College, where he earned a master's degree in forestry in 1906. He joined the Forest Service that year and was sent to Colorado. There, he advanced through the grades and gained experience in a variety of assignments. He moved to Missoula in 1920 as Assistant Forester and advanced to Regional Forester upon Rutledge's departure.

Morrell was a friend of William Greeley and agreed with Greeley that the best course for sound forestry practice and increased production was to encourage Federal-State-private cooperation. He supported the Clarke-McNary Act and sought to extend fire protection over the entire forested areas of Region 1 under its terms. As for Federal regulation of cutting practices on private lands (favored by Pinchot, Graves, and Silcox), Morrell pointed out that the people and hence the legislators had repeatedly voted against it. Therefore, the public did not want Federal control, and the Forest Service should not try to "cram it down their throats." [19]

The Morrell years marked the peak of timber production in Region 1, both on the national forests and on private lands. According to the compilations of Henry Steer, which included all of Idaho and Montana, each year in the 1920's (except for the postwar depression year of 1921), the Northern Region reported an average cut of more than 1.3 billion board feet and on two occasions more than 1.5 billion. This cut was divided among white pine, ponderosa pine, larch, and Douglas-fir, with white pine, mostly from northern Idaho, being the most valuable. [20]

|

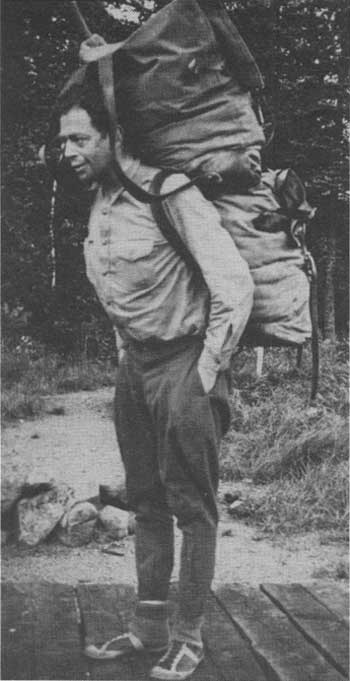

| Bob Marshall on a hike in 1935. |

Bob Marshall

In the summer of 1925, a new character appeared in Missoula, one who was to greatly influence the role of forests in Region 1. At this time, Robert Marshall was only 24 years old, but he was already known as an author, conservationist, avid hiker, armchair socialist, and genial eccentric. Armed with two degrees in forestry, he brought adequate theoretical but little practical knowledge of the work of the professional forester. He was assigned to the Northern Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, and between assignments and on weekends, he explored Montana and northern Idaho, roaming the wild areas that were far from roads or railroads. In the Forest Service family, he became famous for his Sunday 40-mile hikes, which were his normal recreation.

Soon after Marshall's arrival, Regional Forester Morrell assigned him to handle the supply and transportation problems during a major fire on the Kaniksu National Forest. In addition to ensuring that equipment, personnel, and food were dispatched to the camp at the fire front, Marshall regularly walked around the fire line, talked with the firefighters, and recognized them all by name. Many of these men, recruited from the slums and riverfront of Spokane, had surprising backgrounds and soon responded to Marshall's sincere interest. As he said, collectively they were an unsavory bunch, but individually there were a number of superior types. With a keen sense of humor, Marshall also noted the camp food and the time spent by the men in eating their daily meals. On another occasion, he quietly tabulated their camp conversations, which consisted mostly of profanities, sex references, and remarks on bodily functions. Marshall wove these anecdotes together in an article titled "Contributions to the Life History of the Northwestern Lumber jack," which he published in Social Forces in 1929. [21]

Having helped defend the New York State Forest Preserve, Marshall became increasingly interested in preserving wilderness areas that still existed in the West. Taking a cue from Forest Service employee Aldo Leopold, who in 1924 had been instrumental in setting aside the Gila Wilderness in New Mexico, Marshall wrote an article for the Service Bulletin advocating wilderness preservation in the Northern Region and urging that the Forest Service refrain from road building in these primitive areas. He defined a suitable wilderness area as at least 200,000 acres with no permanent inhabitants and no access for mechanical transportation. When another forester, Manly Thompson, attacked the concept of wilderness and dismissed its need because it was used by only a small fraction of the population, Marshall responded, "Wilderness is a minority right!" [22]

Bob Marshall left the Northwest in 1928 to earn a doctorate in plant physiology at Johns Hopkins University. About 7 years later, he, Leopold, and others founded the Wilderness Society. After his death from a heart attack in 1939, the Forest Service designated a large area on the Flathead National Forest as the Bob Marshall Wilderness. It was an area he had repeatedly roamed during his years with the Northern Rocky Mountain Station. [23]

In 1929, Fred Morrell also left the Region to work under his friend Robert Y. Stuart, who had succeeded Bill Greeley in Washington as Chief. Morrell took on the tasks of directing public relations and promoting State and private industry cooperation with the Forest Service. Later, he served as an assistant to the director of the Civilian Conservation Corps, representing the Department of Agriculture in planning corps activities. [24]

|

| Evan W. Kelley Photo by Judson Moore/FS (R1-PAO). |

Evan Kelley

The next Regional Forester was Evan W. Kelley, who came to Region 1 from the Eastern Region and had no previous experience in Montana or Idaho. He served as Regional Forester from 1929 until his retirement in 1944. He made it "his region," and a generation of American foresters identified the Northern Region with "Major" Kelley. Unlike his predecessors, Kelley was not a college man and had no direct connection with Gifford Pinchot and his associates. Yet Kelley became a "forester's forester," popular with most of his associates and well-regarded by officials in Washington.

Kelley was born in 1882 in California and, after a common school education, went to work in the gold mines at the age of 14. Although the pay was good, it was backbreaking work "separating small grains of gold from large masses of earth." In 1904, he became a packer with a chain of 10 mules and a saddle horse, with which he carried supplies for several mines in the central Sierra country of California. He had heard about forest reserves and wrote asking how he could get a job with the Forest Service. While most miners and ranchers thought that the forest reserves would stagnate the economy, Kelley felt otherwise. In 1906, he worked as a forest guard. His initial pay was $60 a month, and he furnished his own saddle horse, pack animals, tools, and food for himself and the animals. He could have earned more at the mines, but he had a "conscious interest in the better treatment of the forests of the country. " [25]

Kelley worked as a guard, assistant ranger, ranger, and acting supervisor before becoming Supervisor of the Eldorado National Forest in California. He transferred to San Francisco in 1914 as a national forest examiner. During World War I, Kelley went overseas as a captain with the 10th Forestry Engineers. Promoted to major, he commanded all saw milling, logging, and road construction operations for several departments in eastern France. His associates described him as athletic, compact, and "ramrod straight," either on foot or horseback. He retained his military rank after the war, always referred to as "Major," which rankled many of his associates who thought the title pretentious. [26]

After the war, Kelley returned to the Forest Service and was stationed in Washington as Inspector of Operations. While there, he compiled the first draft of the "Manual for Forest Development Roads," a new edition of the "Forest Service Trail Manual," a manual on fire control, and also the "Glossary of Fire Control Terms." In 1925, he became Regional Forester of the Eastern Region, which stretched from New England to eastern Texas, but it had little national forest land. [27]

Because of his extensive experience with forest fires, Kelley was sent by Chief Robert Stuart to Missoula to "get a handle" on fire control in the region, at the time recognized as one of the most difficult fire areas in the country. Active, energetic, and personable, Kelley at once worked to "get on top" of the fire problem. He centralized control and supplies and established a remount depot, where a string of pack mules would be ready at a moment's notice. He began to use airplanes to spot fires and air-to-ground radio communication to coordinate work.

In 1931, the disastrous Freeman Lake Fire on the Kaniksu National Forest tested all of the region's innovations and planning. This fire covered approximately 24,000 acres, mostly of valuable white pine. In a few hours, about 1,500 firefighters constructed 75 miles of fire line to try to contain it. Kelley visited the fire line repeatedly, inspected the men's food and camp conditions, and conferred with his foremen. So serious was the fire that even Chief Stuart visited the fire front. [28]

The head of the fireline recalled Stuart's surprise visit:

[O]ne evening on August 5 or 6,...an elderly man dressed in faded bib overalls, a cheap looking straw hat and smoking a corncob pipe arrived in camp. He followed me around, was rather inquisitive as to how things were going; I thought he was a native stump rancher and was rather annoyed....He did not introduce himself, so I inquired if he lived in the area. He said, "No, I'm from Washington, D.C." That didn't ring a bell so I asked more questions and discovered he was Mr. R.Y. Stuart, Chief of the United States Forest Service, Washington, D.C. From then on he received more attention. [29]

One of the young men stationed as a lookout in the fire area was Hume Frayer, at that time a college student who was getting experience through a summer job. Remaining too long at the lookout post with a portable telephone, Frayer found himself cut off by the fire from the trail that was to be his escape route. He started down the hill through the brush, but the fire moved faster, and soon it was a "race against the fire." He plunged down the slope, abandoning the telephone en route and avoiding the tall snags crashing down around him. He finally reached a creek and ran along the other side. At last, he sighted a rancher's house; the rancher was digging a fire trench by his barn. At that time, Frayer fell unconscious on the creek bank, and when he awoke, he was in the back of a truck heading to the ranger station. His clothes were singed, and his shoes were almost burned off. After a short rest and a cup of coffee, Frayer insisted on returning to work and helped build a fireline to protect the ranger station. His narrow escape was a topic of conversation among the firefighters for weeks. [30]

The years 1934 and 1936 were also bad fire years, but the threats were handled more quickly and efficiently because of better coordination and improved equipment. In the summer of 1936, airplanes flew 50,000 miles scouting fires, transporting supplies and men, and taking aerial photographs. Kelley also took legal action against careless campers who left campfires that blazed up later and smokers who caused an estimated 63 fires that summer. In an effort to alert the public to the fire danger, Kelley used placards and slogans and even had movie houses urge hikers and campers to take care in the national forests. [31]

As could be expected, Kelley's work family changed and expanded during his long tenure as Regional Forester. Many men, however, served with him a decade or longer. As of October 1937, the Regional Office staff consisted of the following:

| Regional Forester | Evan W. Kelley |

| Assistant (Operations) | C.C. Strong |

| Assistant (Timber Management) | Elers Koch |

| Assistant (Lands & Public Relations) | M.H. Wolff |

In 1938, Kelley added Perry A. Thompson as Personnel Director. [32]

Within a year after Kelley took charge of the Northern Region, the Great Depression dealt all of the Rocky Mountain States a paralyzing blow. Mills closed, prices fell, and the lines of unemployed men grew ominously longer. In 1932, the wholesale price of lumber, including white pine, had fallen below the cost of production, and many larger mills quit cutting, awaiting an upturn in prices. The total reported cut for the northern Rocky Mountain States was only 359 million board feet, the lowest total since the turn of the century. In 2 years, the number of operating sawmills dropped from 237 to 175.

Timber sales from the national forests also declined. Many large companies found themselves with thousands of cutover acres on which they were paying taxes and receiving no income. Consequently, some owners, including Potlatch, Anaconda, McGoldrick, and the Forest Development Company, donated these lands to the Forest Service—a total of about 500,000 acres added to the adjacent national forests or to primitive areas. This action was in marked contrast to the situation in the Southern States, where the Federal Government negotiated the purchase of cutover lands to form new national forests. [33]

The New Deal

The New Deal recovery program had a major effect on the forests, foresters, and the forest-products industry. As in other parts of the country, the Northern Region subscribed to the Lumber Code of the National Recovery Act, which attempted to revive the industry by reduced production quotas, higher wages, and a shorter work week. Also included in the Lumber Code was the conservation section, known as Article X, which prescribed sustained yield, a comprehensive fire prevention program, protection for young growth, and replanting after logging. Former Region 1 foresters Bill Greeley and David T. Mason, Chief Silcox, and Kelley were skeptical of the ability of the industry to police itself. Ultimately, the article became a model or guide for good forestry practices in the industry, even though the Supreme Court, after several controversial years, invalidated the entire National Industrial Recovery Act. [34]

Of much more lasting importance was the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The CCC, which attempted to bring unemployed young men and neglected land together, was a special project of the president, who had been a strong conservationist all his life. The CCC was a hybrid creature. The Department of Labor identified and enrolled the young men; the Army fed, events housed and clothed them and managed the camps; and the Forest Service (or other Federal agencies such as the National Park Service) directed and supervised the work projects. The first Region 1 camps began operation in the spring of 1933, and by mid-summer, new companies of enrollees were arriving in Missoula every week.

The Army included Region 1 in its Ninth Corps Area, so it managed the camps from its headquarters in San Francisco. Initially, the camps provided tents as shelter, with temporary structures for mess halls and meeting rooms. The camps, thus, were summer camps only and had to be shut down during the severe winter months that characterized the northern region. The Forest Service assigned foresters, usually district rangers or other experienced woodspeople, to supervise the forest projects. Local experienced men were recruited to direct the work and serve as foremen for the several groups; these men were available because most lumber companies had shut down or were operating with reduced forces. During the first year, regular Army officers directed the camps, but by 1934, reserve officers assumed camp S\supervision. [35]

According to local CCC historian Bill Sharp, the first CCC camp were on the Beaverhead National Forest (F—1) and the Clearwater National Forest (F—2). By the end of the summer, 55 camps were scattered among the 17 national forests, plus 2 companies assigned to Glacier National Park and 2 to the State forestry departments. Much of 1933, by necessity, was spent getting organized, laying out projects, and "tooling up."

By 1934, permanent-type camps began to replace the tents. The first permanent camps were Camp Bungalow (F—193) and Camp North Fork (F—23), both on the Clearwater National Forest. Rapidly, permanent structures replaced temporary shelters so CCC companies could live and work through the winter months. Most camps were built for companies of 200, with 4 barracks for 50, a mess hall, a recreation and education building, an office, and a warehouse for supplies and storage. Eventually, these structures became standardized (pre-manufactured) so they could be shipped to the camp site.

A feature of all camps was the voluntary educational program, which enabled youths to complete high school requirements and even take some college-level work. Many Army officers, including General Douglas McArthur, proposed that the corps people be given military training, but this was vetoed by Washington at the top level. The CCC remained a voluntary and civilian enterprise from 1933 to 1942. [36]

The number of camps fluctuated during the life of the CCC. As projects were completed, some camps were closed and the companies moved to new locations. Sometimes camps were moved but kept the same number; other times they received a new number. Often, different companies occupied the same new number. Often, different companies occupied the same camp in different years. There were also "spike" camps, which were detached details working on temporary projects. Most, but not all, camps were under the supervision of the Forest Service. Some were on national parks, State parks, Native American reservations, and private lands. A representative count of CCC activity could be that of June 30, 1935, when Montana listed 32 camps and Idaho 82 (most of these were in northern Idaho). There also were 31 camps in South Dakota and 19 in North Dakota under Region 1 jurisdiction. In comparison, on the same date, California had 155 camps, Wyoming 20, and Washington 69. [37]

Though generally popular, the CCC had numerous problems and attracted some criticism. Some foremen thought that the whole project was a waste of time and money. At least one supervisor felt that all he wanted was for the "foreman to take these boys out in the woods and keep them and yourself out of trouble." Most citizens supported camps of local or regional boys but were critical of camps made up of easterners, especially if they were of recent immigrant stock. Many residents were uncomfortable with or even hostile to the few black companies that were sent to the region.

Elers Koch, an experienced woodsman and conservationist, was skeptical of the CCC program and critical of its performance. He thought the first 6 months of CCC activity were so confused and so lacking in planning that it boded ill if the Army ever had to raise a large force in a hurry. He saw Army officers scurrying around to arrange for buildings but with no knowledge of grades, types of lumber, specifications, or even tools. He also found the food poor. During the first 6 months, there were no expert cooks, there was no training of student cooks, and the enrollees were eating out of World War I mess kits. The Forest Service had to provide tools, cooking ranges, and crockery, some from shutdown logging operations. Koch was particularly critical of the initial practice of sending eastern city boys to the Montana and Idaho camps. He argued that these youngsters had never learned to use forestry tools and had to be taught to perform even the simplest tasks. He also felt that they were largely responsible for the illnesses and injuries reported by the camps. [38]

By 1935, major permanent improvements could be noted in the comfort, food, and work of the CCC camps. The Army had made great strides in making the life of the enrollee more pleasant. Gone were the mattresses of wool sacks stuffed with straw, the double bunks, and the old Army mess kits. Athletic events and social functions were part of the weekly calendar; planned weekend trips were a regular part of the schedule. From a listing of quantities and varieties of food consumed, it was apparent that CCC employees enjoyed a nutritious and abundant diet. The entire organization had stabilized to the point that many supervisors had begun to plan long-term projects and make use of more heavy machinery than had been possible before. [39]

|

| Civilian Conservation Corps Crew digging irrigation ditch for hay lands at Remount Depot, Lolo National Forest, 1934. |

Despite the critics, the CCC youths learned to work and did work. In the white pine area, they fought blister rust, which had threatened to destroy the stands. They built roads and trails, put up signs and markers, and measured distances more accurately. They laid telephone lines and built lookout towers and other structures. They also built badly needed campgrounds, picnic sites, and recreation shelters, especially in the more open terrain east of the Continental Divide. Most of the summer, they fought forest fires. The conditions were right for 1936 to be a bad fire year, but because of the efforts of thousands of young and willing hands, the fires did far less damage than might have been expected.

The CCC reconstructed and enlarged the Savenac Nursery and rebuilt the buildings. On the 17 national forests and on private lands, they planted more than 8 million trees. Among the larger projects, the CCC workers punched through the side of a rocky limestone mountain to build a road to a new camp site. They built a bridge (still in use in 1988) over the West Gallatin River, constructed a pole-and-post treatment plant along Squaw Creek, and even built a new ranger station out of logs.

With any such large body of young men, working in unfamiliar surroundings, there were accidents, some of them fatal. Two World War I veterans drowned while attempting to cross the St. Joe River in December 1933. Lt. Robert Gilmore died from exposure, as did fire guard Harry Halvorsan while on a fire fighting expedition. Three CCC men died while fighting the "Pete King" fire in 1934. One young CCC enrollee slipped and fell into the Clearwater River and drowned in 1936. One young man wandered away from camp and apparently became lost in a snowstorm. When search parties were unable to find his body, even after the spring thaw, the camp commander decided that he was most likely "absent without leave" and dropped his name from the rolls. A year later, blister rust control workers discovered the skeletal remains and clothing. As a result, camp officers reopened the case, held lengthy hearings, and declared the man legally dead. In all, there were about 12 reported fatalities from forest fires, at least 5 drownings, and several other accidental deaths among CCC men working in the Northern Region between 1934 and 1940. [40]

For others, the CCC experience opened the way for a successful career. One such example was Carl W. Wetterstrom. Young, school, and unable to find a job, Wetterstrom joined the CCC in 1933 in northwest Washington, where he worked on a grazing survey. After a year with the corps, he was employed by Region 1. The regional forester assigned him as assistant ranger and later foreman of a CCC camp on the Flathead National Forest. By 1941, he became District Ranger on the Flathead. After a stint with the military forces in the South Pacific, Wetterstrom returned to the Forest Service as District Ranger on the Deerlodge. He eventually rose to become Assistant Forester, Division of Recreation and Lands, in the Regional Office at Missoula. He received a number of citations and awards for his work with water impoundment programs, especially Libby Dam and Dworshak Dam. He retired in 1973. John Breazeale, Tony Jinotti, Blaine Doyle, and W.E. "Curly" Steurwald were among the many other CCC enrollees who later joined the Forest Service and had successful careers in their chosen fields. [41]

During the depression, some were able to bypass the CCC and join the Forest Service directly out of school. One was Lester M. Williamson who, after weeks of waiting, worked as a temporary fire guard in 1935 on the Coeur d'Alene National Forest. He pleased his superiors by his eagerness, and he rose to be Fire Control Officer on the Clearwater National Forest. After a long career, he retired in 1972 with highest praise for his years with the Forest Service. [42]

Kelley summarized the many contributions of the CCC at a press conference in December 1940. Nearly 6.5 million person-days of labor had been expended in the Northern Region since 1933. "Not only have these boys contributed much to the improvement of the national forest," Kelley said, "but the enrollees themselves have received much valuable training. Working with heavy mechanical equipment such as bulldozers, tractors and trucks has equipped these boys with a valuable asset in finding jobs after the loss of their enlistment period." [43]

Evan Kelley had managed Region 1 well during the difficult years of the Great Depression. In 1941, he reported that lumber sales from the national forests had returned to predepression levels and fire losses for the year were among the lowest in history. Less than 1,100 acres had been burned or scorched, thanks largely to the greatly improved efficiency of the CCC crews who had "come a long way" since the early days of 1933. The University of Montana, in recognition of his many achievements and outstanding leadership, awarded Kelley with an honorary master's degree in forest engineering. It was a fitting tribute to an outstanding forester. [44]

There were, during this difficult time in the Nation's history, important accomplishments in forestry in general. Region 1, in particular, helped weather the adversities of war and build a strong base for postwar progress.

Reference Notes

1. E.I. Kotok and R.F. Hammatt, "Ferdinand Augustus Silcox," Public Administration Review II (Summer 1942) 3:240-253.

3. "National Forest Districts, 1911," in Region 1 historical files, Missoula, MT.

4. Ralph R. Widner, ed., Forests and Forestry in the American States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1968), pp. 1-346.

5. Kotok and Hammatt, "Silcox."

6. Wilson F. Clark, "A General History of Custer National Forest," 1982, Custer National Forest historical files, p. 35

7. "Semi-Annual Report, 1917," in Region 1 historical files; Keith Peterson, Company Town: Potlatch, Idaho and the Potlatch Lumber Company (Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1987), pp. 161-163.

8. Michael F. Malone and Richard B. Roeder, Montana: A History of Two Centuries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976), pp. 207-215; Letter, Henry S. Graves to members of the Forest Service, March 19, 1927, in Region 1 historical files; see Roger M. Peterson, "Northern Region Involvement in World War I" (January 1988), Intaglio Collection, University of Montana Archives, Missoula, MT.

11. Silcox to Greeley, July 7, 1917; Greeley to Silcox, July 14, 1917, in Region 1 historical files (memorandums).

12. Journal of Forestry 38 (1940): 4-5; Kotok and Hammatt, "Silcox."

13. Richard H. Rutledge to forest supervisors, September 13, 1917, and September 29, 1917, in Region 1 historical files; Malone and Roeder, Montana, pp. 207-215.

14. Peterson, "Northern Region in World War I."

15. K.D. Swan, "Reminiscences of the Dakota National Forest," in Region 1 historical files.

16. Historical items on D 3 (Sioux District); Beartooth Skyline (Red Lodge, MT: April 1930), in Region 1 historical files.

17. Elers Koch, "Forty Years a Forester," typescript, n.d., pp. 134-143, in Region 1 historical files.

18. Rutledge to Bitterroot forest supervisor, September 18, 1918, in Bitterroot historical files, A—O; Paul J. Culhane, Public Land Politics (Baltimore: Resources for the Future, 1981), pp. 86-87; William D. Rowley, U.S. Forest Service Grazing and Rangelands (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1985), pp. 179-181; William Voigt, Jr., Public Grazing Lands (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1976), pp. 261-73.

19. Journal of Forestry 34 (1936): 130-135, 43 (1945): 851-853, 57 (1959):249.

20. Henry B. Steer, Lumber Production in the United States, 1799-1946 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1948), pp. 13-16, 73.

21. James M. Glover, A Wilderness Original: The Life of Bob Marshall (Seattle: The Mountaineers, 1986), pp. 67-97.

22. Ibid., p. 95; Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1973), pp. 200-208; see Dennis Roth, The Wilderness Movement and the National Forests (College Station, TX: Intaglio Press, 1988).

24. Journal of Forestry 57 (1959):249.

25. Evan W. Kelley to Chief of the Forest Service, January 10, 1944; "Major Kelley Retires after 38 Years," in Region 1 historical files; Journal of Forestry 48 (1950):499-500.

28. Journal of Forestry 48 (1950):499-500. A more pleasurable occasion that Kelley supervised in 1931 was the dedication of an obelisk honoring Theodore Roosevelt, located at Marias Pass on the Continental Divide near the south entrance of Glacier National Park. See Kelley to Horace M. Albright, September 16, 1931, in Region 1 historical files.

29. Henry Peterson, "The Freeman Lake Fire, August 1910," Early Days in the Forest Service (Missoula, MT: Northern Region, USDA Forest Service, 1976), p. 218.

30. Hume Frayer to Mom (his mother), August 11, 1931, in Region 1 historical files.

31. Press releases, Region 1, #737, #744, and #748, July to September, 1936.

32. Ibid., #834 (1936) and #850 (1938).

33. Steer, Lumber Production, p. 16; Press release, Region 1, #698, #794, #801, and #820 (1937).

34. See Thomas R. Cox, Robert S. Maxwell, Phillip Drennon Thomas, and Joseph J. Malone, This Well Wooded Land: Americans and Their Forests from Colonial Times to the Present (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985), pp. 221-222.

36. John A. Salmond, The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1967), pp. 26-45.

37. Ibid., p. 84; Bill Sharp, "The Civilian Conservation Corps and the U.S. Forest Service of Region 1," in Region 1 historical files; Bill Sharp to Henry C. Dethloff, September 18, 1987, with enclosure "The Civilian Conservation Corps in Montana and Under the Fort Missoula CCC District, May, 1933 through July, 1942," Intaglio Collection, University of Montana Archives.

38. Ibid.; Koch, "Forty Years a Forester," pp. 163-170.

39. Bill Sharp, "The CCC and the U.S. Forest Service."

40. Linnea Keating, Brief History of Public Works Programs on the Clearwater National Forest (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1983); Sharp, "The CCC and the U.S Forest Service"; Robert R. Milodragovich to Henry C. Dethloff, July 24, 1989, Intaglio Collection, University of Montana Archives.

41. Carl W. Wetterstrom to Henry C. Dethloff, January 3, 1988, Intaglio Collection, University of Montana Archives; Milodragovich to Dethloff.

42. Lester M. Williamson to Henry C. Dethloff, March 22, 1988, Intaglio Collection, University of Montana Archives.

44. Press releases, Region 1, #901 (1941) and #937 (1944).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

history/chap6.htm Last Updated: 10-Sep-2008 |