|

The National Forests of the Northern Region Living Legacy— |

|

Chapter 5

Wildlife and Fish

After the creation of the national forests of the Northern Region, foresters confronted many preexisting conditions that would affect management practices for much of the region's history. Indiscriminate timber harvest for railroads, mines, smelters, and lumber mills often inhibited natural reseeding and contributed to serious erosion. Smelter emissions and mining left many scars on the land. Overgrazing despoiled once-rich forage covers. Uncontrolled wildfire was an ancient and persistent nemesis of the Northern Region. Sporadic disease and insect infestations required constant vigilance, research, and countermeasures. Significantly, too, the diversity and number of wildlife in the region had been seriously depleted during the 100 years since Lewis and Clark explored the area.

The following historical survey of the wildlife and fish of the Northern Region indicates the dimensions of its wildlife management problem. The discussion on contemporary wildlife management approaches is intended to provide a better understanding of the natural history of the region through a before-and-after perspective.

Thousands of years before the Europeans arrived, aboriginal hunters roamed the northern territories. Their harvest had little effect on the supply or diversity of species. The hunts were seasonal, and game were insulated from attack by the cold and deep snow. Hunters, on foot, used spears or bows and arrows in the pursuit of game. The human population was sparse, and people entered many of the mountainous areas only during the warmer months. The introduction of the horse during the 18th century gave the Native Americans much greater mobility, but this affected their hunting strategy only on the plains, not in the mountains. Even then, their depletion of the buffalo was minimal.

The Lewis and Clark expedition into the northern territories first exposed animal life to the more deadly weapons that could kill at great distances and to the markets of America and Europe. The journals of Lewis and Clark vividly report the great variety of game that, in most cases, they easily shot. [1] The number and variety of animals killed by the expedition, often in excess of what they could possibly use, were indications of things to come. Americans at that time believed that the land and game were inexhaustible; they gave little thought to preservation or conservation.

The journal of Lewis records the plethora of animals everywhere in the area that is now western North Dakota and eastern Montana. He described the "immense herds of Buffaloe [sic], deer, Elk, and Antelopes which we saw in every direction feeding on the hills and plains." There also were two kinds of bears, bighorn sheep, felines, and wolves. In the high country, Lewis said, "game is very abundant; we can scarcely cast our eyes in any direction without perceiving deer, Elk, Buffaloe [sic], or Antelopes." [2] They carefully followed President Thomas Jefferson's instructions to describe and record all wildlife and return with as many specimens as possible.

Wildlife in the area that became Region 1 of the Forest Service remained abundant throughout most of the 19th century. Mountaineers and Native American trappers did deplete the fur bearers such as beaver, fox, marten, otter, and mink in some areas, but they harvested few of the larger game animals. The discovery of gold led thousands of new miners and settlers into the area, and they began to consume large quantities of game "especially elk, bear, buffalo, and deer" for food and for sport. At the same time, the mines began consuming timber for charcoal and for smelters, thus depleting the natural habitat of the wildlife. The railroads brought more people into the area and carried lumber, ore, and minerals out. Hunters began to harvest large amounts of game to feed the miners, railroad gangs, lumberjacks, and the growing populations. Even the Native Americans, now confined to their reservations, began to intensify their harvest of wildlife. Thus, by the end of the 19th century, the pressures on wild animal populations had become critical.

Big-game animals were becoming scarce, and some had been driven completely from their traditional ranges. The depletion of their habitat and hunting pressures drove the survivors into the more remote and inaccessible corners of the area. This retreat, contemporary wildlife biologists note, indicates the adaptability of most wildlife species.

When the first forest reserves were established in the region, little thought was given to wildlife because watershed protection and timber production were major concerns. Most Americans—and foresters—believed that the wildlife would take care of itself as it always had. After Idaho and Montana became States, their authorities made little effort to conserve and protect wildlife. They did establish State game and fish departments, but the primary purpose of such departments (as it is in most States) was to facilitate the harvest of fish and game by the residents. Moreover, the agencies tended to be understaffed, with the agents untrained. The public they served had little or no interest in protecting or preserving wild game; in fact, the public gave wholehearted approval to the destruction of such predators as the bear, mountain lion, and wolf. These species and the populations of elk, deer, bighorn sheep, and mountain goats declined to alarmingly low numbers by the turn of the 20th century. [3]

Few national forests in other Forest Service regions inherited the rich diversity of wildlife and fish as did those in the Northern Region. Thus, it is essential to identify and understand the wildlife and fish resources in the region when the Forest Service assumed responsibility for its natural resources so as to comprehend the management tasks and accomplishments of the agency. Contemporary wildlife and fish management practices are the product of eight decades of research, experimentation, and experience.

|

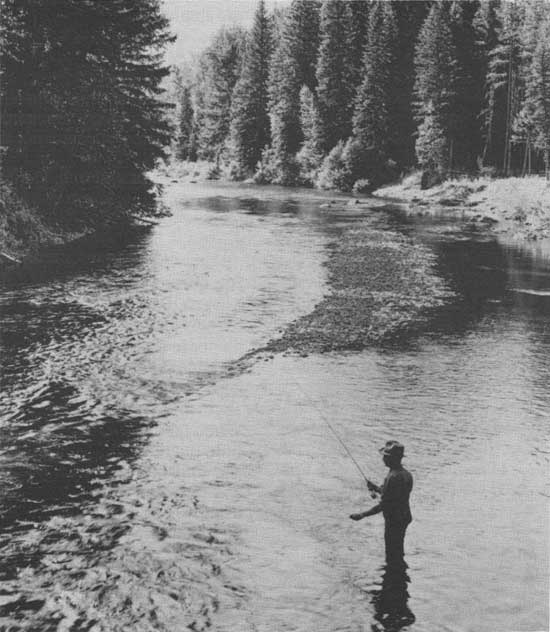

| Fishing in Swan River near Salmon Prairie, 1938. |

Mammals

Grizzly Bears

The grizzly bear is the largest and most dangerous carnivore in North America, and the last major concentration of this species is in the Northern Region. Meriwether Lewis reported the expedition's first encounter with this great bear on April 29, 1805:

[W]e fell in with two brown or yellow bear; both of which we wounded; one of them made his escape, the other after my firing on him pursued me seventy or eighty yards, but fortunately had been so badly wounded that he was unable to pursue me so closely as to prevent my charging my gun; We again repeated our fire and killed him. [4]

A few days later, William Clark wrote, "we saw a Brown or Grisley beare [sic] on a sand beach... which was verry [sic] large and a turrible [sic] looking animal...we Shot ten Balls into him before we killed him" [5]

The grizzly bear was then common across the Northern Region, even at lower elevations, and especially eastward onto the Great Plains. Modern researchers agree that the grizzly was more common at lower elevations in times past. Some even feel that it was more of a plains than mountain animal and that the brownish yellow color is an indication of adaptation to the plains environment.

Lewis observed that before the horse, the Native American on foot with a bow and arrow would find the grizzly a formidable quarry indeed, but the animal was no match for "firearms of a reliable sort." [6] Once firearms became common in the area, especially with the entry of large numbers of whites after 1860, the grizzly was driven from the more accessible lands because of the relentless pressure from hunters, trappers, farmers, and ranchers. There can be little doubt that the 600 or so grizzly bears that now occupy some of the most rugged terrain in the United States do not do so by choice; they are a remnant of vast numbers driven into isolated areas for survival. [7]

One can never know precisely how abundant the grizzly was, but if Lewis and Clark are to be believed and the accounts of "old timers" in the region are accurate, they certainly must have numbered in the tens of thousands. Firearms and trappers took their toll on the grizzly. Grizzly bear coats and rugs found a ready market; trappers could make $100 for a top-quality grizzly pelt. Moreover, grizzly bears are basically fearless, and trappers found them easier to trap than their smaller cousin, the black bear. Forest Service wildlife biologists now believe that there must have been more than 100,000 grizzly in the 19th century. This is in marked contrast to the modern perception of the grizzly as an irascible and solitary creature, ranging over vast tracts of wilderness. [8]

Yet no other animal in the United States excites the imagination as the grizzly bear does, and even its scientific name, Ursus horribilis, conjures up a sense of fear. People view the great carnivorous bear with curiosity, fear, excitement, and a touch of romanticism. By the early 1960's, the grizzly was nearing extinction, and the question was raised whether the grizzly could or even should survive within the continental United States. Charlie Shaw, one of the early foresters of the Northern Region, stated in 1967: "It is reasonable to predict that sometime in the future they will disappear as completely as have the saber-toothed tiger and other animals of the past." Shaw said that he will miss them, but that perhaps they have outlived their time. [9]

Grizzly-human conflicts increased in the late 1960's and 1970's in the Glacier and Yellowstone areas, and some began to call for the total eradication of the bear. A public scare resulted from articles describing the ferocious nature of the animal, and a television movie titled "Grizzly" depicted a giant bear coming out of the mountains to kill and devour people. Finally, in 1974, Congress placed the grizzly bear on the endangered species list, but protection has been difficult. [10]

|

| Grizzly bear. See Judson Moore, Forest Service (R1-PAO). |

Region 1 spearheaded a drive for a cooperative effort to protect and study the bear in its natural habitat. In 1983, Craig Rupp, then Regional Forester of the Rocky Mountain Region, suggested the formation of the Inter-Agency Grizzly Bear Committee. Surveys ascertained total numbers, mortality rate, breeding, diet, and prime habitat, and a program educated the general public about the grizzly. State-of-the-art research tools, such as stun guns, radio collars, aerial observation, and satellite data, were incorporated into the research effort. Potential bear-human conflicts were reduced by capturing troublesome animals, examining and gathering as much data as possible while the bears were comatose from drugs, collaring them if possible, and then transporting them into a more remote area. [11]

From the beginning, it was apparent that a substantial number of grizzlies were full- or part-time residents in the Northern Region. Most of the last remaining suitable grizzly habitat is on the national forest lands of the region. Questions that need to be solved relate to what constitutes the bear's diet during the year, what is required for a good habitat, and how to quiet people's fears. Prime grizzly habitat now includes more than 3.5 million acres, but the bears require even more territory. Public opposition has made it difficult to transplant surplus bear populations into such areas as the Cabinet Wilderness and the Flathead and Kootenai National Forests. [12]

The best estimates are that there are now probably fewer than 700 grizzly bears in the continental United States, a decrease from estimates of years past. Some Forest Service wildlife biologists, however, believe there has actually been an increase in the number because past estimates were inflated. Grizzly recovery is made more difficult by the 2- to 3-year gap between the birth of cubs, which have a very poor survival rate.

In 1988, the largest grizzly concentrations were on the Flathead (165), Lewis and Clark (85), Gallatin (42), and Kootenai (30) National Forests, with a dozen or so located on the Beaverhead, Helena, Idaho Panhandle, and Lolo National Forests. The greatest problem facing the Inter-Agency Grizzly Bear Committee is how to increase the bear population and yet reduce bear-human encounters. Unfortunately, the two largest concentrations of grizzly bears are in and around Glacier and Yellowstone National Parks, which dramatically increases the possibility of bear-human clashes. The bears do not help the situation when they leave the high country and enter the valleys, as they have been doing in eastern Montana in recent years. The long-range goal of transplanting bears to more remote areas, such as the Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem, Bitterroot Ecosystem, and Selkirk Mountains is still under consideration. [13]

Public attitudes about the grizzly rise and fall in direct proportion to the number of bear attacks. Ranchers and farmers still take a dim view of stocking the grizzly in any part of the national forests of Region 1. In a spring of 1988 television documentary on CBS, local farmers and ranchers made it quite clear that they viewed the grizzly as a menace to their operations; they would not hesitate to protect their livestock from the bear. Thus, the grizzly continues to be an endangered species. The Forest Service, however, is providing every assistance to ensure its survival.

Black Bears

Numerous in the past and still so today, the black bear was hunted by Native Americans, early settlers, and contemporary big-game hunters. Smaller and less aggressive than the grizzly, they were relatively easier game, even for the bow and arrow. More gregarious and less selective in their habitat requirements, they are easier to manage and have increased in numbers in response to management and hunting restrictions. The public regards the black bear as a sort of "teddy bear" or "Smokey Bear," and farmers and ranchers do not feel as threatened by them as they do by the grizzly.

Black bears have remained stable in population in Region 1, at an estimated 21,128. Of these, the largest number reside on the Idaho Panhandle (4,275), Flathead (3,340), Kootenai (approximately 3,200), and Lolo (2,540) National Forests. The Idaho and Montana Departments of Fish and Wildlife together allow up to 2,500 animals to be harvested by hunters. [14]

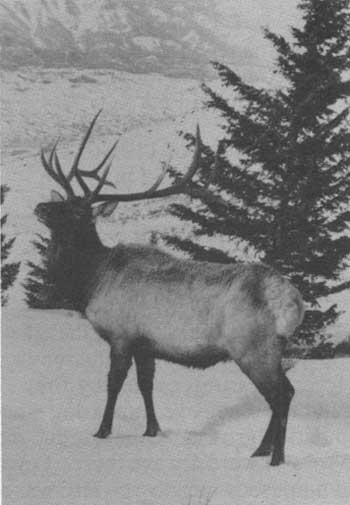

Elk

The Northern Region takes great pride in the restoration of the elk to its former abundance. The Forest Service was a major participant in that successful program. Everyone views the elk as the primary big-game animal in the region, and with good reason. Not only is the elk a noble-looking animal, but it is very large and a difficult quarry. Lewis and Clark reported elk; they were constantly shooting them for meat from the time they left the big bend of the Missouri and crossed the plains of eastern Montana into the mountains. Elk were plentiful at lower elevations, but once in the high country, they were noticeably scarce. [15]

Within the century, the demand for sport and for meat to feed miners, railroad crews, lumber workers, and growing populations eradicated the animal from the more accessible areas at lower elevations. Farmers and ranchers shot the animals in their normal wintering grounds in the lower elevations for meat and because they competed with domestic livestock for forage. The remaining smaller herds were driven into the high country.

|

| Bull elk on Gallatin National Forest Photo by C.R. Joy, March 1962. |

These small fugitive herds tended to concentrate around ancient salt licks and open areas in the high valleys. Unlike the woodland caribou, the elk cannot forage in deep snow and consequently are forced to move down the sides of the mountains, perhaps competing with domestic livestock. As they migrate between their summer and winter ranges, the elk are vulnerable to hunters' guns. State game laws in the past tended to be very permissive, allowing the harvest of game anywhere during the prescribed hunting season. During their migration in the late 19th century, elk herds had to literally run a gauntlet of hunters, a veritable "slaughter alley." Often, the hunting season was too long and during the time when the herd's general health was poor. [16]

The lowest point for the elk herds in the Northern Region seems to have occurred between 1890 and 1910. Population counts had clearly dwindled, and the Forest Service, on whose lands 80 percent of the elk lived, and local sportsmen became concerned. In 1912, in cooperation with the sportsmen, the Forest Service transplanted a small number of elk to the Cabinet Mountains, to help nature rebuild. The first reliable elk census was taken in 1920; 10,700 animals were recorded. By 1930, population counts reached 20,500.

Serious interest and efforts to study the diet, reproduction, diseases, and habitat requirements of the elk began among foresters in the 1920's. In 1923, the Flathead National Forest began a detailed study of wintering elk populations on the forest. Crews were sent in and spent up to 6 months in the backcountry, observing and gathering data. Harvest figures from the forest also revealed a slow but steady increase in the elk herd, from 140 in 1925 to 257 in 1935 to about 920 in 1953. Other studies conducted in the 1930's answered many of the basic questions about the elk's life cycle. Extensive trapping operations were carried out, and the animals were examined and marked before release. As one retired ranger said, "I trapped many an elk, and released him with his neck collar flapping as he ran." [17]

Public education and cooperation with State authorities eventually resulted in the establishment of restricted hunting seasons and harvest permits. There was no profit in protecting and nurturing herds on national forest lands if they were going to be indiscriminately shot on private or State lands. Today, State and Federal agencies and private organizations, such as the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, help ensure that there will be elk for today's hunter and to inspire the wonder of future generations. Stronger enforcement and other controls have been placed on hunting.

Summer and winter ranges are better managed and protected. Sanctuary zones have been established between hunting areas and such protected areas as Yellowstone National Park.

In 1984, the Northern Region reported a herd of 119,863 elk, second only to the size of the herd in Region 2. In that year, 18,955 elk were taken by hunters. The herds have remained reasonably stable over the past several years, and it is estimated that the herd has now attained its maximum population for the size and condition of the habitat. [18]

Explanations for the substantial increases in the size of the elk herds since 1910 are varied. The most common explanation is that the increase of forage and forest clearings caused by fire—and especially the 1910 fires—and the extensive lumbering since World War II have enabled population growth. Others argue that vast open grasslands within the forests were always there. Lewis and Clark, for example, crossed numerous meadows. Fire was a constant at any time. Thus, the 20th century fires are not the explanation. [19]

Modern wildlife management practices certainly have been a positive factor. One view, which does not deny the importance of open country for elk forage, stresses the removal of the predators that preyed on the elk, including grizzly bears, mountain lions, and wolves. Foresters and wildlife specialists are quick to point out that modern game management practices do work. The conservation of the elk enables the public, as a forester stated in the 1930's, to enjoy "considerable food in the form of meat, and its inspirational value [which] ranks highest." [20]

Woodland Caribou

Perhaps the most exotic large animal in the northern forests is the woodland caribou, an American-style reindeer found in the remote Selkirk Mountains of the Kaniksu National Forest (a unit of the Idaho Panhandle National Forests). So little was known about these shy animals, nicknamed "Big-Foot," that they long remained a mystery to the Idaho Department of Fish and Wildlife, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Forest Service in Region 1. Attempts to count the animals invariably ended in controversy, but all agreed that the caribou lived in small herds of only a dozen or so and had never been as numerous as elk or deer. Recent cooperative efforts between the State of Idaho and the Forest Service have resulted in the first reliable data on the animal in its natural habitat. The animals are shy, slow to reproduce, subject to many diseases and parasites, and vulnerable to predators. [21]

Until recently, their isolated ranges provided a degree of protection. Improved roadways constructed since World War II, however, have brought poachers into the protected ranges. Canada's completed Highway 3, which runs across prime caribou habitat just north of the American border, has cost the lives of many animals that have been lured onto the highway by the salt used to clear the ice, only to be struck by passing automobiles. In 1984, only 17 caribou were counted on the Kaniksu. Region 1 subsequently entered into a cooperative agreement, through the auspices of the Chief Forester, providing for the implanting of new caribou herds from Canadian or Alaskan stock. In 1987, a herd of a dozen woodland caribou from Canada were successfully implanted on the Kaniksu, and plans began to be developed for other movements. [22]

Wildlife biologists have discovered that many caribou characteristics are opposite to the elk. Instead of open grass prairies, the caribou requires a heavy growth of climax conifers to winter well. As the snow deepens during the winter, the caribou's splayed feet allow it to walk on the snow and eat the lichens on the trees higher and higher as the winter snow progresses. Forest Service botanists estimate that it takes 50 years for a tree to mature and rise above the snow line and another 50 years for a tree to support quality lichens.

Public awareness will play a major role in halting poaching, deliberate or accidental, and more careful driving in the forests will reduce losses from that source. Region 1 and the Forest Service have committed considerable time and resources to preserve the woodland caribou for future generations to enjoy. [23]

Deer

The plight of the mule deer and its much smaller cousin the white tail, was much like that of the elk; there was little effort to protect and regulate hunting until the situation became critical. Lewis and Clark reported deer on a daily basis and shot them for meat. The much larger mule deer tended to occupy higher elevations, while the whitetail seemed to prefer lower country, especially open valleys. Studies of the deer populations by the foresters revealed much information about the life cycles and problems faced by the deer. [24]

Early reports conducted by rangers who spent many months in the field and in isolated winter cabins stressed two cardinal points. First, some sort of orderly management of the deer and regulation of the hunter were needed. Second, predator control would be most helpful. One report, for example, with accompanying photographs, estimated that one particular mountain lion that had been killed had been averaging three deer kills each week during the winter. [25]

After World War II, the adoption of State hunting regulations and predator control began to provide deer protection, and populations began to increase markedly. The Forest Service, often in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Idaho and Montana Departments of Fish and Wildlife, has produced numerous studies on deer management. The implementation of policies resulting from these studies seems to have produced significant results. Both the mule and whitetail deer are increasing faster than any other species of wildlife in the region; they have become a common sight. Only a few years ago, they did not exist. During the 1960's and 1970's, offroad vehicles became common, and some hunters used them to literally drive the deer. Road closures and new restrictions on such vehicles have helped solve most of those problems.

The latest deer census in 1984 listed 151,267 mule deer, placing the Northern Region in a tie for fifth among the national forests for mule deer population. The largest mule deer herd is on the Lewis and Clark National Forest (38,000), followed by the Gallatin (25,050), the Custer (17,505), and the Beaverhead and Lolo (14,000 each). However, there were only 77,024 whitetails counted. Whitetail deer are probably the most adaptable of all the larger game animals, and their continued increase in the region is expected. [26]

|

| Bighorn sheep. Credit: Danny On, Forest Service. |

Bighorn Sheep

The first complete description of the Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep appears in the journals of Lewis and Clark. The bighorn was fairly common in the early 1800's, even in flat country. Clark reported that their meat was considered a delicacy, and they were frequently shot in preference to other animals. [27]

The public image of the bighorn today is that it is a denizen of lofty, craggy mountainsides where only they and mountain goats can survive. In reality, the bighorn prefers fairly rough lower mountainsides and protected valleys. For example, the open rolling wheat country of northern Idaho, between the Clearwater and Nez Perce National Forests, was at one time prime bighorn sheep habitat. Accessibility to such land by early settlers had entirely removed the sheep from the area by the late 19th century.

Through cooperative efforts between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and State agencies, the bighorn has been successfully reintroduced into large areas of their former habitat. Once virtually gone from the Northern Region, they are now proliferating to the extent that they are a nuisance on some highways, and controlled hunting is allowed. [28]

The implantation of new herds has been a delicate process. In one case at Kemiah on the Clearwater National Forest, the death of one large buck brought the implantation experiment to an end. [29]

A major problem that has not been wholly resolved is that State and Federal game regulations do not apply to Native American Reservations. Most tribal organizations cooperate closely with the States and with the Forest Service in game management programs and hunting regulations, but one lone hunter can do irreparable damage to the best of management plans. Today, there are somewhat less than 5,000 bighorn sheep in the Northern Region, and almost 400 are harvested each year under the permit system. Bighorn are found in 10 of the 13 national forests of the region, with the largest concentrations occurring on the Lolo and the Lewis and Clark National Forests. [30]

The Mountain Goat

Lewis and Clark encountered the mountain goat only through secondhand information. The Shoshonis showed skins of the goat to the party, and Lewis and Clark commented on the beauty and softness of the hides and duly reported their existence.

The goat apparently had never been as numerous as the bighorn sheep, had always been shy, and had preferred the higher, more rugged elevations. As had the bighorn, the mountain goat dwindled to critically small numbers, but they also have been repopulated. They are still found only in the most isolated parts of the forests, but they do exist on each of the national forests of the Northern Region. They are less tolerant of civilization than the sheep. In 1984, there were 4,327 mountain goats, and 192 were harvested under controlled hunting programs. [31]

|

| Mountain goat. |

Moose

The moose is the largest mammal on the national forests of Region 1, excluding the relatively small number of buffalo (bison) located on the grasslands. At one time, the moose's survival was more threatened than that of the other large animals because of its unique and restrictive habitat requirements. Moose prefer the marshy borderlands of lakes and streams, where they browse on aquatic vegetation. Because of their huge size, they need such large areas for sustenance, and those habitats are relatively scarce. Known for their irritable nature and dangerous behavior, moose are usually left alone by all. Even though they are not known for their beauty or noble look, they awe those who happen to see one.

Moose have responded well to modern game management and are now stable in numbers. Census counts for 1984 place the moose population at 9,959, with 489 harvested under the permit system. Moose flourish in all of the northern forests, with the greatest concentration on the Kootenai (1,500) and the Gallatin (1,225) National Forests. [32]

|

| Buck Antelope on Gallatin National Forest Photo by L.J. Prater, 1947. |

Pronghorn Antelope

The pronghorn antelope was once much more numerous across the eastern portion of what is now the Northern Region. Lewis and Clark noted many sightings of pronghorn until reaching high country. Antelope are natural residents of flat, open country, where they rely on their keen eyesight and speed for survival. This habitat preference brought them into conflict with the farmers and ranchers who also preferred such terrain for their livestock operations. This competition for the range has driven the pronghorn into more isolated and protected grassy meadows within the national forests. [33] There are approximately 4,500 antelope in the region, and a harvest limit is placed at about 450. The great majority of the pronghorn range on the Custer National Forest meadows and grasslands, with scattering groups on the Beaverhead, Lewis and Clark, Helena, Deerlodge, and Gallatin National Forests. [33]

There are approximately 4,500 antelope in the region, and a harvest limit is placed at about 450. The great majority of the pronghorn range on the Custer National Forest meadows and grasslands, with scattering groups on the Beaverhead, Lewis and Clark, Helena, Deerlodge, and Gallatin National Forests. [34]

American Buffalo

The American Buffalo, or technically the bison, is a minor inhabitant of the Northern Region. Only about two dozen roam the national forest lands. Buffalo were once common across most of the plains in the region and survived into the early 1880's, when the final great herds were slaughtered for their hides.

Increasing the number of buffalo on the national forests would not be a problem because this animal responds quite well to the management policies used in raising cattle. They are very hardy animals. As one of the early settlers in the area commented, "A buffalo is hard to freeze or starve to death." Most of the buffalo on forest lands are drifters from Yellowstone National Park or from other herds. At present, there are no plans to increase the small herd that ranges on the Gallatin National Forest. [35]

Mountain Lions

The mountain lion, or cougar, was and still is the chief predator that confronts most of the game animals in the Northern Region. Once much more abundant than it is today, the lion was trapped and hunted for many years without any restrictions. Farmers and ranchers fought the lion at home and in the State legislatures because they threatened the safety of their livestock. Wildlife biologists for a time also believed that the mountain lion should be strictly controlled because it threatened the survival of large game herds. Rangers frequently reported hunters killing as many as a dozen cougars and several dozen coyotes in the 1920's and 1930's as the "fight" against predators continued. This view began to change in the 1930's. Wildlife biologists and others working with the herds of deer and elk in the region began to believe that predators were necessary in good game management because they "kill off the weak, crippled and diseased animals first, thereby keeping healthy, strong breeding stock in the deer herd." Despite the attacks by humans and the lack of positive "reinforcement" programs, the mountain lion has survived quite well and seems to have maintained a reasonably stable population of approximately 1,700 in the region. Mountain lions are present in all the forests in varying numbers; they range over extremely large territories. [36]

Wolves

Americans probably have a preoccupation with the wolf as much as they do with any other single large animal. All early travelers and settlers in the Northern area talked about the great packs of wolves—in most instances, the Rocky Mountain gray wolf—ranging from the plains into the mountains. Lewis and Clark wrote about how unafraid the wolves were, almost appearing as tame as domestic dogs. Nearly all accounts from early settlers report how numerous wolves were and that they were a danger to livestock. No other animal in the United Sates has been so cursed and hounded to near oblivion as has the wolf. Moreover, wolf pelts brought good prices in the late 19th century. The territorial legislature facilitated the extermination of wolves by placing a bounty of $1 to $2 a head in the 1880's. The bounty was raised to $3 in 1895 and $15 in 1911—a very attractive figure and well in excess of average daily wages for the time. [37]

Clearly, the rapid decline of the wolf population derived from the combined efforts of the Government, hunters, farmers, and ranchers—all of whom regarded the wolf as a potential killer of livestock. Also contributing to that decline was the destruction of the wolves' food supplies, prominently the large-game animals such as the elk and deer. Many also believe that the introduction of the deadly poison strychnine about 100 years ago caused its rapid decimation even in relatively remote areas. [38]

Contemporary management decisions to reintroduce the wolf have raised controversies, much like those surrounding the protection of the grizzly. Conservationists would prefer to implant animals in suitable habitat on Federal lands, but local people are afraid that their domestic livestock will once again become the target of roaming bands of wolves.

The best estimates are that there may now be a dozen wolves on or near national forest lands. Foresters believe that the wolf is now naturally recolonizing in northwest Montana and should be allowed to continue to do so under protected conditions of the Threatened and Endangered Species Act. A wolf den, the first reported in more than 50 years, has been identified, and the Nez Perce National Forest reported a pack of six wolves in 1987. A radio-collared female wolf was detected on the Kootenai. Whether she was alone or had traveling companions is unknown. Regional Forester John W. Mumma indicated that while the Forest Service is taking no direct action in implantation or reintroduction, "its primary role...in wolf conservation is to provide suitable habitat." [39] After that, it is up to the wolf.

Coyotes

No discussion of animal life in America would be complete without mention of that wily hunter-singer-scavenger, the coyote. No other creature that has been so systematically slated for destruction has so successfully survived and thrived. There are several reasons for the coyote's successful adaptation to the modern era. First, as the larger and more powerful carnivores have been removed, the coyote has moved into the vacant niche.

Second, an intelligent, tough, and adaptable animal, the coyote seems to enjoy adversity and can live within or outside of civilization.

More than likely, there are more coyotes in Region 1 today than there were in the best times of the 19th century, but population figures are simply unknown. Coyotes are regarded as "varmints" and can be hunted and trapped all year long. How much damage they do to domestic livestock and game animals is debatable, but they tend to prey on the weak and old. [40]

Lesser Mammals

A large variety of smaller animals have played an important role in the history and economy of the region, and they continue to be important today. The first penetration of the region of a lasting nature came from the mountaineers and trappers in pursuit of the beaver and other fur-bearing animals, such as the fox, otter, marten, fisher, mink, and other members of the weasel family. The unrestricted hunting and trapping of fur bearers continued well into the 20th century, resulting in some parts of the country becoming denuded of fur bearers, and they remain so today.

The beaver has made a significant comeback; it is now a common sight along streams and ponds. Fishery biologists are more appreciative of how a beaver dam can improve fish habitat, and they are now using them as accomplices by stocking the beaver in remote areas to halt sediment buildup and provide new spawning beds. [41]

Many of the more important fur bearers were probably never abundant, and by the time the era of fur trapping ended, these animals existed only in isolated and secluded pockets and remain there today. Programs to establish new populations of marten and otter have been reasonably successful, and more are anticipated in the future. One animal on the threatened and endangered species list is the black-footed ferret. [42]

Northern woods folklore has depicted the porcupine as the friend of the person lost and starving in the wilderness because it was so easy to capture and kill. This imagery led to early protection being extended under State law. As the number of predators in the region declined, the porcupine flourished, with little to fear except the automobile. During the 1920's, regional silviculturists developed an extensive program to reforest conifers. Much to their dismay, they discovered that the harmless porcupine loved to dine on the tender terminal buds of the young trees. After considerable debate, which continues today, a program of porcupine control was instituted; it resulted in a substantial reduction of the porcupine population. [43]

Several kinds of squirrels, rabbits, and hares afford hunters sport and meat. Rodents such as the chipmunk, ground squirrel, and marmot give vacationing Americans many hours of amusement and provide essential food in the food chains of wildlife. While the wolverine, badger, bobcat, northern lynx, and polecat barely survive, the raccoon and skunk seem to flourish within the confines of civilization.

Fish and Fisheries

The fisheries of Region 1 have been important since aboriginal times. Fish were often a mainstay in the diet of some tribes. Lewis and Clark caught fresh trout and salmon and dried trout for future use. The people of the Northern Region take great pride in the quality of fishing and in the "blue ribbon" streams, such as the Clearwater, Gallatin, Madison, and Jefferson.

Although much of the region's fishing is not actually conducted on national forest lands, almost all the streams originate on national forest watersheds; thus the quality and flow of water depends on Forest Service watershed management. The acts establishing the first forest reserves stressed water conservation. Today, the region can boast of 22,500 miles of streams, including 2,600 miles of "nationally recognized blue ribbon waters" and 1,650 lakes containing 170,000 acres, with many alpine lakes nestled in the high country. [44]

A conservative estimate of the fish produced annually from regional waters is 9 million. The headwaters of the Columbia River Basin in Idaho provide 1,700 miles of habitat for anadromous chinook and steelhead (migratory fish), producing 1.3 million smolt yearly and 462,000 pounds of fish—with production increasing annually. The national forests of Montana do not have the anadromous fish found in Idaho (except for the Kokanee salmon, which is a form of anadromous fish). However, Montana does have outstanding fishing provided by westslope cutthroat, rainbow, bull (landlocked Dolly Varden), mountain whitefish, and arctic grayling, all native, as well as the introduced brook and brown trouts, to mention the more important species. [45]

Although consideration has long been given to water quality control, mining, lumbering, grazing, and road building have not been conducive to maintaining good water quality and favorable watersheds. In years past, many streams within the region were destroyed as fish habitat. Some streams were dredged for gold, and the resulting removal of sand and gravel, and the dump deposits along the banks, either silted the streams or stripped and increased the gradient. [46]

Lumbering activities often broke stream banks down by denuding them or causing erosion, which contributed to silting and greater water velocity. Livestock ate the riparian zone along the shore, broke down the banks, and in general caused a muddying of the stream. Fires could do the same kind of damage by burning away the cover along the banks, thus contributing to erosion and silting. [47]

Conservationists have strongly criticized road and dam construction within the region as endangering the fisheries. Studies of the Hungry Horse Dam on the Flathead River system, conducted by the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks and financed by the Bonneville Power Administration, while placing no blame, do note that a major problem above the dam is the streams' sedimentation. [48]

Public concern and more technically accurate procedures for gathering information have resulted in more careful monitoring of the impact of projects within the forests on water quality. Mining operations are more carefully controlled. Timber harvests are more closely monitored, and clearcutting is limited to only 40-acre tracts. Grazing lands are checked for signs of overgrazing. If road construction destroyed water quality in the past, the results were accidental rather than deliberate.

Current, more sophisticated engineering and ecological impact studies have enhanced construction techniques. Early ranger handbooks specifically required that roads be on grade and that consideration be given proper drainage, especially at stream crossings. "Old hands" quickly admit that mistakes were made. For example, although placing culverts in a fast-moving stream was recognized both as bad engineering and bad watershed management, culverts were (and are) used at times when no other alternative existed. [49]

Modern forest plans require that roads or other structures be built only on the basis of clearly defined objectives. Before a road can be built, there must be communication among road engineers, water quality engineers, archaeologists, landscape architects, and wildlife and fisheries biologists. Such consultation aims to perform a job with the least impact on the total environment. An environmental impact statement is required, and public comment is formally invited.

Inasmuch as the harvest of fish is regulated by a State, as is the harvest of animals, fisheries specialists in the region face the same confusing array of often-conflicting authorities and interests as does the wildlife specialist. Much of the key habitat is under the authority of the Forest Service, but the product of that habitat is under the authority of the State and strongly influenced by the private sector. A fishing stream, for example, may traverse State-owned, private, corporate, national park, Native American, and Bureau of Land Management lands. Fisheries plans, programs, and policies must incorporate the collective interests of all parties. [50]

At one time, the western slope of the Continental Divide in Idaho was the spawning ground for a tremendous chinook salmon and steelhead trout fishery. These anadromous fish spent their first year in the cold mountain streams before traveling downstream to the Pacific Ocean, where they matured into adults, only to return to their birthplace to spawn and die. Over the years, dams were constructed downstream, which not only made it difficult, but often prevented the fish from completing their journey. A deterioration of water quality and growing fishing pressure contributed to a decline in the annual migration. [51] Programs, in cooperation with various agencies and authorities, were initiated in the 1950's to mitigate some of these problems. Fish ladders have been constructed around some of the dams to allow the fish to continue upstream, and smolts are captured above the dams and transported downstream to prevent their destruction in the turbines. [52]

The case of the Kokanee salmon has been similar to that of the steelhead trout. Flathead Lake, which is not on national forest land but is fed by streams originating from those forests, supports the Kokanee salmon. The Kokanee salmon was introduced into the lake in 1916 and at once made it home. The lake replaces the ocean in the fish's life cycle, and spawning takes place in those streams emptying into the lake. For many years, the Kokanee furnished anglers with spectacular fishing, but the catch has begun to decline since the 1970's. [53]

The introduction of the Mysid shrimp into Flathead Lake in 1980, ostensibly as a new food source for the Kokanee, is believed by some to have actually contributed to the decline of the Kokanee. The shrimp proved to be competitors with, rather than food for, the fish. Another major change in the lake environment occurred with the construction of Hungry Horse Dam in 1953, which blocked the ascent of some streams. Moreover, the uneven release of water from the dam results in sharp fluctuations of water levels in the streams and lake so as to adversely affect the spawning beds. Fish redds along the edge of Flathead Lake and in the streams emptying into it below Hungry Horse Dam often suffer low-water periods, exposing eggs to desiccation or freezing. Although at this time no Kokanee spawn on any streams of the national forests, some fisheries biologists believe that with proper preparation, some of the streams on national forest lands could be developed into spawning areas for the Kokanee. [54]

The Northern Region is one of the most active regions in fish habitat improvement for both resident and anadromous fish. It has been a leader in researching and implementing habitat improvement techniques. Extensive research into sediment effect on the salmon in Idaho can apply to other fish species. The importance of beaver dams and ponds for fish production resulted in successful transplantings into parts of the Lolo and Beaverhead National Forests since 1983, and immediate improvement has been achieved. Experimentation with log and boulder weirs and the placement of tree snags and wire enclosed structures have produced good results on the Clearwater and Nez Perce Rivers. Cooperative studies, such as that conducted jointly in 1958 by the Forest Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks on the effect of pesticides on trout streams, have produced measurable improvement in water quality and fisheries management practices. [55]

Adequate funding has been one of those inevitable constraints on fishery improvement programs. Recent congressional legislation, however, has helped alleviate some of those problems. In 1976, Congress passed the National Forest Management Act, which allowed the national forests to use funds derived from timber sales (under the 1930 Knutson-Vandenberg Act) to improve habitat within the boundaries of the sale. Many forest supervisors found it convenient to use these funds for fisheries improvement because streams in the cutover areas often suffered damage. In 1983, special funds from the Bonneville Power Administration also became available, and major beneficiaries have been the Clearwater and Nez Perce National Forests. The Nez Perce has been awarded more than $1.2 million over a 10-year period to improve chinook salmon and steelhead trout fisheries on the South Fork of the Clearwater. The Clearwater received (in 1988) more than $250,000 for similar improvements on tributaries of the Clearwater River, such as the Lochsa River and Lolo Creek. [56]

These supplemental funds have "allowed placement of 338 in stream structures to enhance cover, spawning, and rearing habitat; [and] provided 25 acres of barrier removal and spawning bed improvement." The use of snag trees, sediment removal, riparian zone improvements, and especially log and boulder weirs have reduced water velocity and created feeding, hiding, and resting sites for fish in many streams. [57]

Thomas J. Kovalicky, Supervisor of the Nez Perce National Forest, has been a leader in recent efforts by the region to improve fishing and fishery habitat. Since he became supervisor, forest budgets for fisheries projects rose from $22,600 in 1982 to $515,000 in 1988. "Kovalicky," the Lewiston, Idaho, Morning Tribute stated, "has carved himself out a niche among conservationists as a U.S. Forest Service line officer who champions anadromous fish, salmon and steelhead, as vigorously as the trees in the national forests." [58]

Birds

The forests of Region 1 support a variety of birds, including songbirds, birds of prey, waterfowl, shorebirds, and ground dwellers. The bald eagle, which is listed on the threatened and endangered list, nests in several forests. Conservation methods implemented over the past several years have resulted in stabilizing the eagle population, which now seems to be growing. The peregrine falcon, however, is faring less well. Its piercing cry was once heard over much of the region, but toxic material released into the environment, loss of habitat, and illegal killing and capture have reduced the bird to minimal populations all across the United States. Several years of surveying potential habitat and nesting sites for the peregrine falcon within the region's forests resulted in a successful hack (release) of peregrine on the Gallatin National Forest in 1984. This proved so successful that five additional hacks were conducted on the Nez Perce in 1987. [59]

Waterfowl are a major resource of the region. They nest where the habitat is suitable, and some stop to rest on their long flight south on the Central flyway and to a lesser extent on the Mississippi and Pacific flyways. Some waterfowl spend all year in areas of the region where enough open water remains through the winter. The most notable waterfowl in the region is the trumpeter swan, which is a resident. Although the Red Rock Preserve, its primary home, is not on national forest lands, the preserve is surrounded by forests used by the birds. Trumpeters declined to marginal numbers after World War II, but they have now rebounded to much larger populations. [60]

The giant Canada goose (Branta canadensis maxima) once thought to be extinct, has been found nesting on the national grasslands of Custer National Park. During the last few decades, they have multiplied and divided into a number of new colonies. Geese and ducks find nesting throughout the national forests—particularly on the Custer National Forest, which contains thousands of prairie "potholes," both natural and human made. These potholes produce thousands of nesting sites when there has been adequate rainfall. The Forest Service cooperates with State agencies and such organizations as Ducks Unlimited to create and improve these nesting and rearing ponds. [61]

The Custer National Forest is unique for its variety of birds. At one time, the prairies and plains of the United States abounded in quail and partridge-type birds, as well as a number of different doves or pigeons. As the prairie sod was broken and plowed under for crops or overgrazed by livestock and as birds were hunted throughout the year, some species came close to extinction. When the Forest Service assumed administrative responsibility from the Soil Conservation Service for the national grasslands, it continued those policies already operating to stop erosion and to allow the land to revert to its natural state. Grazing is permitted in some areas and is used as a tool to improve the habitat, just as buffalo and other animals did before the Europeans arrived. Extensive oil and gas exploration and production have developed in parts of the national grasslands, but Forest Service biologists do not feel that this has an adverse effect on wildlife when conducted under proper controls. [62]

The thick grass cover that has developed encourages the ground-dwelling birds, and some have made dramatic recoveries. The greater prairie chicken is on the protected list, and its population fluctuates so much from year to year that biologists are concerned for its survival. On the other hand, the sharptailed grouse responds well to management; it has become so well established that there is now an open hunting season. Similarly, the introduced ring-necked pheasant and gray or Hungarian partridge have adapted well to the grasslands environment and provide excellent hunting. [63]

Birds that thrive (or survive) in the region range from the bald eagle to lesser raptors, such as the "sensitive-listed" smaller prairie falcon and merlin. There also are several kinds of owls and smaller birds, ranging from tiny hummingbirds, such as the black-chinned and broad-tailed, to the beautiful western bluebird, the noisy gray and Steller's jays, and many varieties of sparrows, wrens, warblers, orioles, and tangers. [64]

Although the Forest Service is keenly aware that publicity on wildlife tends to center on those species that catch the public's attention, such as the grizzly bear and the bald eagle, many creatures depend on sound management of the national forests. They are not forgotten by the agency.

Wildlife Programs and Legislation

In 1899, Congress enacted legislation that recognized the recreational value of Federal lands and the integral role of wildlife. Shortly thereafter, when Theodore Roosevelt became President, a genuine concern for the protection of wildlife developed, but a system for extending that protection did not exist.

When the forest reserves were transferred to the newly created Forest Service in 1905, national forest lands had become a refuge for much of the big game in Region 1. Thus by default rather than by design, the Forest Service found itself responsible for the habitat of much of the wildlife of the region, but without control over the laws and practices affecting the harvest of the game and fish, which was the prerogative of the States. Initially, State agencies and the public harvest of game conflicted with the Forest Service's interest in conserving wildlife numbers. As the State agencies became more professional and the Forest Service became more oriented toward game management, cooperation in game management and protection began to develop. One of the first indicators was the deputizing of forest rangers as game wardens by the States to control poaching.

...a genuine concern for the protection of wildlife developed, but a system for extending that protection did not exist. |

Although the rangers tended to vigorously enforce State game laws, the public was not always appreciative, and State-Federal conflicts erupted. Hunting clubs, outfitters, guides, and local residents tended to prefer free and unrestrained access to the wildlife. Even those who were not hunters tended to regard wildlife, and especially predators, as competitive creatures who should be destroyed, or at best ignored. The farming and ranching electorate of Montana, Idaho, and the Dakotas were keenly aware that large herds of deer and elk competed with sheep and cattle for grazing and that wolves and mountain lions destroyed lambs and calves. Thus, the realization that wildlife is a public asset to be protected has come slowly.

A milestone in the development of cooperation for game management and protection occurred with the creation of a Division of Wildlife Management within the Forest Service. Effective December 1, 1936, the Chief Forester's directive advised:

In recognition of the growing importance of the preservation and management of the wildlife resources for the National Forests of the United States, and the increased public interest in these resources, the Secretary of Agriculture has created in the Forest Service a Division of Wildlife Management. [65]

At the time, Regional Forester Evan W. Kelley remarked that "Creating the Division of Wildlife Management is of great importance to Region One. Wildlife," he said, "is a crop of the national forests in the same sense as trees and grass are products of the land." [66]

The new focus on wildlife management required public education as well as scientific habitat and wildlife management programs. More study and research would be required in an area that had largely, as had wildlife, been "taken for granted." The Regional Office explained to the public, "Sound wildlife management demands scientific research and study involving little known biological factors, land economic influences, and relationship to other land issues." It had become clear "that pioneer conditions of wildlife cannot be restored." [67] Yet in several contexts, the Forest Service has attempted to do just that—to restore conditions to their primitive or "original" condition as nearly as possible. The designated wilderness areas of the national forests within the region, as well as the national grass lands, seek to duplicate as nearly as possible those conditions that existed before the entry of humankind.

Not until 1960 did Congress spell out the importance of wildlife by declaring in the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act that the national forests are to be administered for "outdoor recreation, range, timber, watershed, and wildlife and fish purposes." This act gave official sanction to practices long in use within the Forest Service and especially in Region 1. [68] Subsequently, the National Environmental Policy Act (1969) required alternative solutions to problems of a harmful nature to any aspect of the environment, and in 1973, the Endangered Species Act required the protection and conservation of "threatened and endangered fish, wildlife and plant species." All Federal agencies were directed to cooperate to further the purposes of the act. [69] The National Forest Management Act (1976) and the Pacific Northwest Power Planning Act provided a financial footing for wildlife protection in Region 1.

Speaking of the national forests in general, past conservation leader (and former Forest Service employee) Aldo Leopold's explanation of the work of national forest managers has special meaning to those who administer, labor, and live in the Northern Region:

The administration of the National Forests of America has for its real purposes the perpetuation of life, human, plant, and animal life. Of first importance is human life, and so closely related is this to tree and plant life, so vital are the influences of the forest, that their problems have been fashioned into major problems of forest management and administration.

Of next importance and ever increasing is the problem of animal and bird life. Driven from their once great range by civilization the wildlife that was at one time America's most picturesque heritage has found refuge in the National Forests. [70]

During the 20th century, forest and wildlife managers and the American public have a better understanding of the sometimes delicate associations among forest habitats, wildlife, and human use of the renewable and nonrenewable resources of the lands.

Reference Notes

1. Bernard DeVoto, ed., The Journals of Lewis and Clark (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1953).

3. Ibid., p. 103; Montana Almanac, 1959-60 (Missoula, MT: Montana State University, 1958), PP. 42-60; W.M. Rush, "Elk Management Plans, Part I," USDA Forest Service, Region 1, 1933, pp. 1-152, see pp. 12-13.

4. Journals of Lewis and Clark, p. 102.

7. USDA Forest Service, A Last Stand for Grizzly Bears: The Role of the Forest Service (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1984); Interview with Nathan Snyder, August 20, 1988, in Intaglio Papers, University of Montana Archives, Missoula, MT.

8. Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, Grizzly Tracks (Ogden, Utah: 1986), pp. 1-2; Victor H. Treat, interviews with Ralph Space, August 13, 1988, and Dan Davis, August 16, 1988, Orofino, ID.

9. Charlie Shaw, The Flathead Story (Kalispell, MT: USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, Flathead National Forest, 1967), p. 114.

10. Kootenai National Forest Plan: Final Environmental Impact Statement (Libby, MT: Kootenai National Forest, 1984), Appendix D—Grizzly Bear Management, pp. 5-8; USDI, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Grizzly Bear Augmentation Tests (Missoula, MT: 1987), pp. 4-8; "A Last Stand for Grizzly Bears" (brochure); Treat interview with Snyder.

11. Grizzly Tracks; Treat interview with Davis.

12. "Group Growls about Grizzly Plan" and "Betrayed on Bear Issue," in Missoula, MT, Missoulian (July 15, 1988); Charting the Course (Missoula, MT: Forest Service Grizzly Bear Conservation Program, Interagency Report, 1986), pp. 3-9.

13. Victor H. Treat, interview with Bill Ruediger, Missoula, MT, August 11, 1988; Treat interview with Davis; Grizzly Tracks, pp. 5-6; USDA Forest Service, Region 1, Annual Wildlife and Fisheries Report, 1984 (Missoula, MT: 1984), pp. 4-5; Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management in the Forest Service (Washington, D.C.: USDA Forest Service, 1984), pp. 52-54, 87-88, 115.

14. Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, pp. 52-54, 87.

15. Journals of Lewis and Clark. pp. 28, 96, 150, 405-409; Rush, "Elk Management Plans," p. 2.

16. Rush, "Elk Management Plans," pp. 5-8, 22, 136.

17. Ibid., p. 2: Montana Cooperative Elk-Logging Study (Missoula, MT: USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, 1980), pp. 30-75, 82; Ralph Space, The Clearwater Story: A History of the Clearwater National Forest (Missoula, MT: USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, 1964), pp. 1-52.

18. Rush. "Elk Management Plans," p. 137; Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, p. 41.

19. Treat interviews with Space and Davis.

20. Rush, "Elk Management Plans," p. 140; Treat interview with Space.

21. USDA Forest Service, Cooperative Agreement with British Columbia, State of Idaho, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Selkirk Mountain Caribou Management Plan/Recovery Plan (Portland, OR: 1985), p. 115; P. Flinn, Caribou of Idaho (Boise, ID: Idaho Department of Fish and Game, 1954), pp. 15-31.

22. Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, p. 88; Wildlife and Fisheries Program Report (Missoula, MT: USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, 1987).

23. USDA Forest Service and other agencies, "The Woodland Caribou: Bigfoot of the Selkirks" (brochure); Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984; Wildlife and Fisheries Program Report, 1987.

24. Letter from Bitterroot Forest Supervisor John W. Lowell to Idaho Deputy Game Warden, C.K. Hjort, May 18, 1925, Bitterroot historical files, P-2; Shaw, The Flathead Story, p. 7; Rush, "Elk Management Plans," pp. 2-13.

25. USDA Forest Service, Region 1, "Fish and Game" Bitterroot Winter Game Studies, 1936," typed report, Idaho portion, 1938.

26. Kenneth Hunter, "Some Predictions About the Effects of Season Manipulation on Mule Deer," Dillon, MT. Tribune-Examiner (March 30, 1977); Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, "Forest Road Closures," Helena, MT: Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, n.p.; Amos E. Enos, ed., Audubon Wildlife Report (New York: The National Audubon Society, 1986), pp. 128-129.

27. Journals of Lewis and Clark, pp. 115-117.

28. Victor H. Treat, interview with Tom Holland, Dillon, MT, August 17, 1988.

29. Treat interview with Davis.

30. Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, pp. 52, 54, 87.

31. Ibid., pp. 53, 55, 89; Journals of Lewis and Clark, pp. 162, 227.

32. Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, pp. 53, 55, 88; Fred Morrell, "Big Game on the National Forests of Montana," USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, 1924, pp. 1-5.

33. Journals of Lewis and Clark, p. 163.

34. Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, pp. 52, 87.

35. Victor H. Treat, telephone interview with Dr. Wilbur Clark. Helena, MT. September 27, 1988.

36. Script for radio broadcast from Billings, MT. March 4, 1930. Material provided to the Regional Office by the Rod and Gun Club of Billings, MT. One sentence said, "predators must be exterminated." In historical files, Region 1; Region 1, Press releases #701, March 26, 1936, and #696, March 16, 1936; Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, pp. 53, 59.

37. Journals of Lewis and Clark, pp. 103, 121; Joseph K. Heward, Montana, High, Wide and Handsome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1943), p. 123.

38. Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Status and Coordination Meeting (Whitefish, MT: USDA Forest Service, Region 1, 1988), p. 8. The wolf had become virtually extinct in the Northern Region.

39. Ibid., pp. 2-3; Nez Perce National Forest Annual Report (Grangeville, ID: USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, Nez Perce National Forest, 1987), n.p.

40. Annual Wildlife and Fisheries Report, 1984, pp. 6, 9; USDA Forest Service, Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management in the Forest Service, Fiscal Year 1983 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1983), pp. 16-34; Dave Filius, Interview with Sula Rancher John McClintic, 1977, pp. 15-16, in Bitterroot historical files, A 1680; Management Prescription for the Badlands Planning Unit, Final Environmental Statement (Billings, MT: USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, Custer National Forest, 1974), p. 23.

41, Annual Wildlife and Fisheries Report, 1984, p. 6.

42. Ibid.; Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, Fiscal Year 1983, pp. 16-34.

43. Press release, Region 1, #673, January 7, 1936.

44. Journals of Lewis and Clark, pp. 142, 393.

45. Wildlife and Fisheries Program, 1987," USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, Missoula, MT. 1987 (brochure); George D. Holton, "Identification of Montana's Most Common Game and Sport Fishes," Montana Outdoors (May/June 1981); USDA Forest Service, Northern Region and Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, "A Fishing Guide to the Gallatin National Forest," n.d., n.p.

46. "Value Analysis of Crooked River Habitat Improvement Project," Nez Perce National Forest, Grangeville, ID, 1984, pp. 2-4.

47. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Enhancing a Great Resource "Anadromous Fish Habitat" (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1984), pp. 10-11; Rick Stolwell, Project Leader, "Red River Fish Habitat Improvement," Clearwater National Forest, 1984, n.p.

48. See Robert G. Ketchum and Carey D. Ketchum, The Tongass: Alaska's Vanishing Rain Forest (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1987). Many articles have appeared in periodicals such as Life, Readers Digest, Progressive, and Sports Illustrated. And see Bonneville Power Administration, Division of Fish and Wildlife and Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, Effect of the Operation of Kerr and Hungry Horse Dams on the Reproductive Success of Kokanee in the Flathead System (Kalispell, MT: 1988), pp. xi, 10-11.

49. Victor H. Treat, interview with Carl Wetterstrom, Missoula, MT, August 12, 1988.

50. Forest maps often appear like a checkerboard, with sections of land of different colors signifying type of ownership. Victor H. Treat, Interviews with L.H. Dawson, Kalispell, MT, August 9, 1988, and Al Espinosa, Orofino, ID, August 15, 1988.

51. Richard P. Kramer, "Evaluation of Physical and Biological Changes Resulting From Habitat Enhancement Structures in the Upper Lochsa River Tributaries," Clearwater National Forest and, Bonneville Power Administration, 1987, pp. 2-4.

52. USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, Nez Perce Forest Report, "Roads and Fish Conflict and Solution," Grangeville, ID, 1986, typed report, Tom Kovalicky, "Wildlife and Fish Leadership in Multiresource Forest Land Management," Paper presented to SAF Convention, Fort Collins, CO. 1985.

53. Effect of the Operation of Kerr and Hungry Horse Dams, pp. xi, 10-11.

54. Treat interview with Dawson; Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, "Kokanee Salmon in the Flathead System," Helena, MT, n.d., n.p.

55. USDA Forest Service, Northern Region, "A Guide for Predicting Salmonid Response to Sediment Yields in the Idaho Batholith," Missoula, MT, 1984, n.p.; Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, p. 32; USDA Forest Service, Cooperative Agreement with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, "Effects of Forest Insect Spraying on Trout and Aquatic Insects in Some Montana Streams," 1988, n.p.

56. USDA Forest Service, Region 1, "Value Analysis of Crooked River Fish Habitat Improvement Project," Nez Perce National Forest, 1984, n.p.; Kramer, "Evaluation of Physical and Biological Change."

57. South Fork of Clearwater: A New Beginning, pp. 5-7; Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, p. 18.

58. Lewiston, ID, Sunday Tribune (March 6, 1988), pp. 1, 8.

59. Wildlife and Fish Habitat Management, 1984, p. v; Nez Perce National Forest Annual Report.

60. Audubon Wildlife Report, p. 1026; Annual Wildlife and Fisheries Report, 1984, p. 6; Visitor Information (Dillon, MT: Beaverhead National Forest, 1987), p. 7.

61. Victor H. Treat, interview with Wilson Clark. Missoula, MT. August 9, 1988; Management Prescription for the Badlands Planning Unit, p. 23.

62. Victor H. Treat, interview with Joe Salinas, Missoula, MT, August 11, 1988; USDA Forest Service, Region 1, "Custer National Forest," Billings, MT, n.d., n.p. (folded brochure).

63. "Custer National Forest" (brochure); Management Plan: Rolling Prairie Planning Unit, Little Missouri National Grasslands, Final Environmental Statement (Billings, MT: Custer National Forest, 1975), pp. 10-27.

64. Sioux Planning Unit, Environmental Statement (Billings, MT: Custer National Forest, 1976), pp. 14-15; Sheyenne National Grasslands Management Plan (Dickson, ND: Custer National Forest, 1979), pp. 117-119; Martin D. Arvey, A Checklist of the Birds of Idaho (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1947); Roger Tory Peterson, A Field Guide to Western Birds (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1961); USDI, Waterfowl Tomorrow (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1964).

65. Michael Frome, Whose Woods These Are: The Story of the National Forests (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1962), p. 181; Press release, Region 1, #675, January 11, 1936.

67. Ibid.; Press release, Region 1, #767, November ll, 1936.

69. Audubon Wildlife Report, 1986, p. 105; USDA Forest Service, What the Forest Service Does (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1979), p. 28.

70. Frome, Whose Woods These Are, p. 181.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

history/chap5.htm Last Updated: 10-Sep-2008 |