|

Zuni Mountain Railroads Cibola National Forest, New Mexico

|

|

HISTORIC OVERVIEW

Introduction

The time of the steam logging railroad in the Zuni Mountains of western New Mexico was very brief, not much over thirty years. The logging railroads represented a series of attempts to develop a capital-intensive, organized lumber industry in the area. The railroads in the woods carried logs to sawmills, which in turn shipped lumber and wood products to markets as distant as California, Colorado and Missouri. For a variety of reasons, the industry did not develop into a permanent one. Once all the trees were gone, the lumbermen closed their mills, pulled up their railroad tracks, and moved elsewhere.

Among the reasons for the rapid demise of industrialized lumbering were the complexities of land and timber ownership, the excessive distances logs were hauled from the woods to the sawmill, and a lack of well-identified stable markets. During their short life, however, the logging railroads made their mark on the woods in the form of clear-cut areas, remains of roadbeds and bridges, and the sites of several towns.

The purpose of this study, which was requested by the Southwestern Region of the USDA - Forest Service, is to provide a history and description of the logging railroads that ran in the Zuni Mountains. In addition, descriptions of typical artifacts and engineering features of the logging railroads are included where appropriate to aid those responsible for subsequent studies and surveys of the cultural resources in the Cibola National Forest.

|

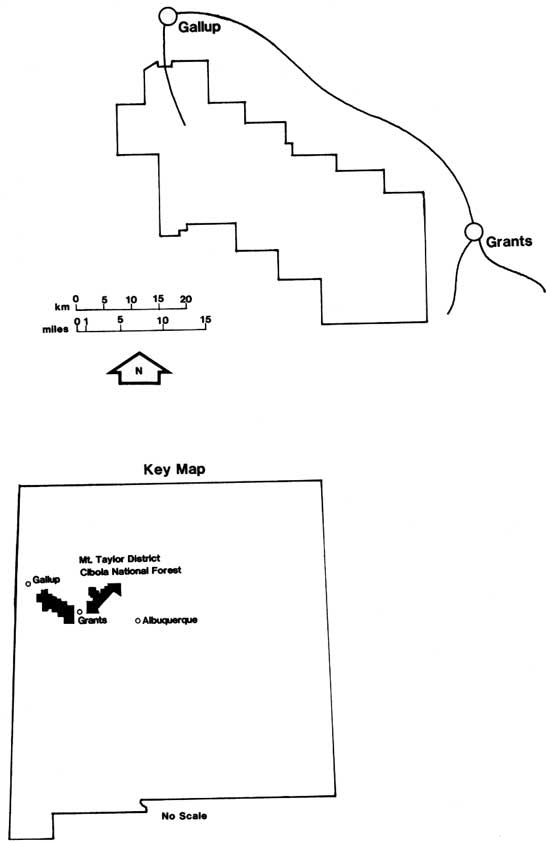

| Locational maps showing the Grants - Gallup vicinity and some units of the Cibola National Forest. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The numerous railroad lines built in the mountains have left behind many signs of their existence. In the dry climate of the high country, significant mileages of roadbed have survived well enough to be readily followed on the ground or detected on aerial photographs. In many places, culverts, small bridges and earth fills remain nearly intact. And, in a number of locations, major structures—rock cuts, large fills, and cribbed log trestles—remain much as they were when last used. All around these vestiges of the railroad era may be found random artifacts ranging from common track spikes to a car body part or two left following on accident.

Three examples of railroad construction, recently examined by one co-author in company with Forest Service archeologist David Gillio, vividly demonstrate the nature of logging railroad remains to be found in the Zuni Mountains. The Pine Canyon railroad exemplifies upland construction with a minimal roadbed connecting substantial cribbed log bridges or fills across shallow watercourses. The Valle Largo railroad is of heavy construction with rock cuts and earth fills of substantial dimensions. The third line, the McGaffey Company main line in Six Mile Canyon, represents a carefully engineered line laid out by the engineering staff of a main line railroad to the peculiar requirements of the logging industry. Each line is discussed fully in the appropriate section of the report.

Part of the activity of logging railroads in the Zuni Mountains predates the formation of the National Forest. Fortunately, some key business and engineering records have survived, which form the basis for this history. Beyond that, the information has been gathered by several people over a period of years as an effort of historical interest rather than a formal history. Nevertheless, material presented here is believed to be a reasonably comprehensive picture of the business and technical history of the logging railroads.

The history of the lumbering industry in the Zuni Mountains is closely related to that of the main line railroad that runs north of the mountains, originally built as the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (A&P) and now known as the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF). The relationship had several facets. Initially, the A&P was the source of the land on which the pine timber grew. The land was part of a Federal land grant earned when the A&P was initially built. Next, the main line was one of the larger customers for lumber and timber, especially in the form of crossties and bridge timbers. And last, the main line was an integral part of the transportation system which carried the logs from woods to mill, and the finished products from mill to distant markets.

Atlantic & Pacific Railroad

The possibility of a railroad north of the Zuni Mountains was first explored in 1851-1853, when Lt. A.W. Whipple ran a survey from Ft. Smith, Arkansas, west to Tehachapi Pass in California. Called the Thirty Fifth Parallel route, the line crossed the Rio Grande in the vicinity of Isleta Pueblo, and followed the Rio San Jose past Laguna and north of Acoma. Crossing the lava beds in the vicinity of Fort Wingate, the line swung northward to avoid the heavily timbered Zuni Mountains, and then continued westward into Arizona (Greever 1954:2,3).

The importance of the Thirty Fifth Parallel route was confirmed when, in 1866, Congress approved an Act chartering the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. The Act authorized construction of a railroad from Springfield, Missouri, through Albuquerque, and along the Thirty Fifth Parallel to the Colorado River and on to the Pacific by the most practicable route (Greever 1954:20).

Congress encouraged the company with aid in the form of land. The provisions under which this aid was to be granted were complex:

To aid construction the United States gave the railroad a right of way one hundred feet wide, with additional space where stations or shops proved necessary, all exempt from taxation in the territories. More important, it authorized the company to earn a land grant, justified as necessary to encourage a route for the mail and the military, of the alternate, odd-numbered sections for twenty miles on either side of the line in the states and forty miles in the territories. Since it had previously disposed of some acreage in these so-called place limits to homesteaders and others, as replacement for acreage so lost it established on additional strip ten miles on either side of the place limits in which the railroad could pick so-called indemnity land from the odd-numbered sections. It would not allow the company to select any mineral property, with the customary exception of coal or iron. It stipulated that the railroad must earn the land by actually building its line, with the right received from three inspecting federal commissioners to additional property with each twenty-five miles of road accepted as finished (Greever 1954:20,21).

Although the provisions of the land grant itself remained in force, the affairs of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad through the 1870s were very unsettled. By April 1880, when the AT&SF reached Albuquerque, the A&P had been reorganized as the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway (SLSF) or "Frisco" as it was commonly called. The SLSF at this time extended only from St. Louis to Vinita, Indian Territory, a distance of 361 miles. And this effort had earned the railroad 510,497.86 acres of land (Greever 1954:22-28).

In order to build a railroad from Albuquerque to California, the AT&SF and SLSF joined forces in 1880. The A&P was revived under joint ownership, and began to build a railroad west from a junction with the AT&SF at Isleta, New Mexico, during the summer of 1880 (Greever 1954:29). As construction was pushed across New Mexico and on into Arizona during 1880 and 1881, the timber resources of the Zuni Mountains became very important. No other timber was available near the route of the railroad in New Mexico, and it became the source of crossties for the A&P in that area. J.M. Latta had the contract to provide ties for the A&P. Latta subcontracted on order for a half-million ties, enough for 200 miles of single track, to John W. Young in late 1880 with delivery required by September 1881. Young established a tie-cutting camp at Bacon Springs near the continental divide (Peterson 1973:131). Bacon Springs was close to the Site along the track called Cranes's Station until March 1882, when it was renamed Coolidge, after T. Jefferson Coolidge. a director of the company. The railroad station name was changed to Dewey in 1898 and then to Guam in 1900 (Figure 1) (Telling 1954 :214-218).

| (omitted from the online edition) |

| Figure 1. The Santa Fe Railway station at Guam, New Mexico. Originally called Crane's Station, the site was named Coolidge in 1882, Dewey in 1898, and finally Guam in 1900. The station was the shipping point for railroad timber during the construction period of the 1880s. (Orsen Frederick Lewis. Keith Clawson collection) |

During the 1880s, three additional lumbering enterprises operated in the mountains south of Coolidge. The first was owned by James and Gregory Page, who set up a sawmill and lumber yard at Coolidge. Later, in 1889, Henry Hart and W.S. Bliss operated mills south of Coolidge. And soon afterward, Bliss joined forces with J.M. Dennis in another lumbering operation nearby (Telling 1954:214-215).

By this time, the A&P had extended its service into California, and had helped open up a very active lumber industry around Flagstaff, Arizona, as well (Bryant 1974:93-94). The stage was set for the expansion of lumbering in the Zuni Mountains.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

cibola/cultres6/sec1.htm Last Updated: 02-Sep-2008 |

Electronic edition courtesy of the Forest History Society. |