|

The Early Days: A Sourcebook of Southwestern Region History — Book 1 |

|

THE WAHA MEMORANDUM

In response to a request from Mr. Gifford Pinchot, Mr A. O. Waha, who had a long and productive career in the Forest Service, recorded his memories of the early days. That portion of his manuscript dealing with his experiences in District 3 follows.

|

Gila Forest Reserve

In due course of time, notice was received from Washington that I had passed the examination and my appointment as a Forest Assistant at a salary of $1000.00 per year, effective July 1, 1905, followed. I reported for duty along with many of my associates who had also received appointments, and after a day or so I learned that I was to be assigned to the Gila Forest Reserve in southwestern New Mexico. My traveling companion was Arthur C. Ringland who was assigned to the Lincoln Forest Reserve in New Mexico.

Silver City, a mining and cattle town, was the headquarters of the Gila, R. C. McClure, Forest Supervisor, was a pompous, pot-bellied gentleman from Kentucky who affected the dress of a Kentucky colonel by wearing a black broad-brimmed felt hat, a flowing end black bow tie, a black Prince Albert coat (in those days we called them for some unknown reason "go to hell" coats), and gray checked trousers. His characteristic pose was to hold his cigar in his mouth at an angle of about 45 degrees and keep his thumbs in the armholes of his vest. His office was in a small brick house that previously had been a residence.

The transfer of the Reserves from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture had been made effective February 1, 1905. McClure was without Civil Service standing, having only a political appointment. While he was quite cordial in meeting me, I could not help but feel that he was not wholly pleased with my assignment, probably thinking that "this young squirt of a technical forester was sent here to get my job." The only work he had in his office for me at the time was in reviewing files and in making copies of his letters on an old copy press. That system was abandoned in a year or so, I believe, but strange as it may seem. the Land Office is still using it. (Robert Ripley may find this out in time.)

A little incident to show that McClure's heart was in the right place, but which made him appear both ludicrous and ridiculous, occurred previous to my assignment. I doubt if he ever lived it down — it was one of those things that people simply do not forget. It seems that McClure was riding horseback, and was carrying an umbrella — horsemen in those days carried a quirt and a slicker tied to the cantle of their saddle. Whether or not he actually opened up the umbrella while riding in the rain I do not know. At any rate it was bad enough simply to be packing an umbrella while on horseback. But when he came to a pasture and saw a calf that had been born only a few hours previously and shivering in the cold rain and meanwhile bawling plaintively, McClure dismounted, wriggled through the barbed wire fence and on reaching the calf stood alongside with his umbrella held over it for protection against the elements. Evidently, so the story has it, this was too much for the mother cow grazing a few yards away. She became infuriated and with head down chased McClure back over the fence and the haste in which he was forced to take the fence made somewhat of a mess of his pants. Thereafter McClure was a wiser man. but the natives could never be convinced of this.

The day after my arrival on July 18, 1905, I was told by McClure that I was to take charge of all timber sale work. The Gila Reserve at that time comprised about 3 million acres and included what is now called the Datil Forest. It was a territory about 150 miles long and 75 miles wide. There were five forest rangers.

The situation on the Reserve was somewhat "hot" because of recent additions of territory where mining companies and local settlers had been getting their mining timbers, lumber and cordwood simply as a matter of course. Much timber that had been cut in trespass was there to be measured and later settled for by the trespassers. After buying a horse, I started out on July 22 with Rangers Geo. Whidden and Jack Case, two hardboiled, hard riding rangers who were much older than I and who had been around considerably. Whidden had been in the Army previously and had been in skirmishes with Indians, having been stationed at Fort Custer, while Case had been an itinerant cowpuncher. I shall always have a sneaking suspicion that McClure had either told them to kill me off or that they themselves had planned to do so. The first day we rode 38 miles over the burning plains country. I was quite inexperienced in riding and as a result. I was so done up after this long ride I could scarcely crawl out of the saddle and on reaching the ground, it was extremely difficult to move, my muscles being so sore. I doubt if there was a spot on me that didn't ache.

It was not until early in August that we returned to Silver City, but only for the purpose of stocking up with supplies, for our pack trip was to be resumed immediately. After the first week in the saddle, I had become hardened to riding and felt quite at ease in handling my horse.

* * * * * * * * * *

The following is my diary for August 2, 1905

At Doyles' ranch, arose about 5 a.m. and after a good chicken breakfast we packed up and got started about 8 a.m. The first mishap was a runaway. "Phoenix" Case's pack horse was trotting along when his pack slipped. This made him excited and he started down the road at top speed. The pack soon fell off, scattering cooking utensils, corn, etc., along the road.

Had a 40-mile ride into Silver City and it was exceedingly hot. Stopped about an hour at the stage station, unpacked and fed the horses. Had a chat on current topics with the stage keeper.

Arrived in Silver City about 9:30 p.m. It was very dark and we had quite a time getting across the deep arroya to the corral. Stopped to see McClure on way. Fed and stabled the horses, which took some time as there were seven horses in our outfit. After this task was finished we went to the Chinaman's chow house and got a good feed, the first bite we had had since 6 a.m. McClure came down and talked with us, telling us his troubles since the addition to the Forest Reserve by President's Proclamation of July 21, 1905. Returned to the corral about 12:30 a.m. and spread our blankets on the floor of the stable - was very tired and could have slept any old place. Disturbed several times during night by the crowing of several ambitious roosters who were perched on bales of alfalfa just above our heads."

* * * * * * * * * *

In addition to writing a diary of this kind we had to submit a monthly report of daily service like the attached sample [Unfortunately, the referenced sample was not available when the author compiled this study]. It was facetiously called the "bed sheet" report.

Regardless of winter snows, timber sale work continued. The following diary for several days in February 1906 covers an experience which I have often recalled.

* * * * * * * * * *

Saturday - February 10. Rain and snow; very disagreeable weather. As we (Ranger Bert Goddard who later became Supervisor of the Datil and Tonto Forests) had made up our minds to start for Kingston today, rain or shine, we saddled up about 11 o'clock and started in the rain. Stopped at Fort Bayard and lunched with Peck (Allen S. Peck and Wilbur R. Mattoon were then stationed here managing a forest tree nursery. At this time I was making my headquarters in Pinos Altos, "Tall Pines", which had once been a flourishing mining camp) after which we rode to Santa Rita. Decided to stay there overnight for it was already late and we were soaking wet. Watched the masked ball in the evening. Time 8 hours. Distance 18 miles.

Sunday - February 11. Still snowing and very wet and sloppy. Were in saddles at 7 a.m., rode to Teel's place on Mimbres river just above San Lorenzo, had dinner and fed horses. Left Teel's at 12 o'clock, starting for Kingston. All went well until we struck the higher altitudes and encountered a regular blizzard. Trail very dim and snow became deeper and deeper. In Iron Creek it was nearly three feet deep and we had a struggle to get through. Reached Wright's old deserted cabin near head of Iron Creek at 5 o'clock: we were wet to the skin and awfully cold, while our horses were just about all in. After much consultation and arguing we decided to stay at the cabin overnight. Spent an awful night since we had no chuck and no bedding. Brought horses into cabin with us. They had to share some of their corn with us. Place was infested with trade rats. While I was dozing during the night, Goddard shot one that was on a beam directly over me, and it fell on me causing a rude awakening. For warmth we burned scraps of wood including shingles that we could rip off. Took turns in keeping fire going; slept about 3 hours. It had snowed from time to time during night. We were not at all sure that we could make it out; visions of eating horseflesh and other things entered our minds.

Monday - February 12. Awfully glad to see daylight and we were ready to start at 7:30 a.m. The weather was clear and cold, but we soon found there were other things to occupy our minds. The snow was very deep, practically 3 feet on the level on the west side of the range, and to make traveling still worse, the trees and bushes were covered with about a foot of snow which one could not escape. We soon became soaking wet and then when we reached the divide we found the snow so deep our horses could not get through, so we led them, breaking trail through thick oak brush. This leading and breaking trail was done for at least two miles or until we reached the canyon in which Kingston is located. Took the idle people of Kingston by surprise; they could scarcely believe that we had come over the Black Range. Met Mr. Skitt at Mrs. Prevost's store, and he took us to his house and saved our lives by giving us something to eat. I was wet to the skin and spent considerable time around the stove. Found that we could room and board at Mr. Prey's house and there we found everything to the good; meals great and a bully bed.

Tuesday - February 13. Rode to Hager's sawmill in Southwest Gulch; scaled some timber and marked trees in Case No. 80, snow being knee deep or more. Met Hager and Phelps, found out what they wanted and informed them of the raise in price of sawtimber. Had dinner at sawmill shack. Distance 10 miles - Time 9 hours.

Wednesday - February 14. Inspected land applied for by Peter March for agricultural purpose and made report on it in evening. Issued several free use permits also.

Thursday - February 15. Again rode to Hager's sawmill, blocked out sale for Phelps, lessee of Hager's mill, and Goddard marked timber for cutting while I rode to South Percha to fix up Dawson. The latter accompanied me and upon arriving at the area, he concluded that the canyon was too rough to warrant his spending a large amount of money on a road and only get out 100,000 linear feet of mining poles. So we came back to Southwest Gulch and blocked out an area at the head of the canyon for 5,000 feet. Tried to mark trees but owing to depth of snow, it was possible to mark only a few. Returned to Kingston in time for supper.

Friday-February 16. Goddard rode to Southwest Gulch to finish marking trees while I spent the day in the house writing up timber sale papers. Played hearts in evening with Col. Harris (the youngest old man I ever saw) and Tom Robinson (the groceryman teller of bear stories and experiences in driving a bunch of burros to St. Louis and thence east). Had oyster stew made by Colonel Harris about 11 p.m., after which we played whist until 12 o'clock. Expect to leave in morning for headquarters.

Saturday - February 17. Bid our friends goodbye and left Kingston at 8:45 a.m., riding back over the same trail. The snow had melted considerably and we had no difficulties in getting through. Upon reaching Iron Creek we put our horses right through and we surprised ourselves by reaching the ranger's cabin in Bear Canyon at 5 o'clock. Distance 50 miles. It was bully to get down into the Mimbres Valley and see man ploughing in their fields. Stopped at Mimbres mill and asked for Potter (had expected to go out to Crittenden's sale and mark timber) but not finding him, we left work and proceeded to Bear Canyon. All done up. but after a good supper of boiled beef, felt better so played a couple of games of "sluff."

Life on the Gila was never dull and when I was transferred to Albuquerque as an inspector in June 1907, but not before I had had a detail in the Washington Office, it seemed like giving up home ties. Not only was it hard to leave my friends. but also my horses. I had become so greatly attached to my horses that it seemed wicked to sell them and not know how they would be treated.

All of my work on the Gila was not confined to timber sales. In fact I was assigned from time to time to grazing activities, mining claims examinations, boundary surveys, special use cases and other miscellaneous work. I learned the language of the stockmen and miners. At times, McClure would place me in charge of the office during his absences. On one of those occasions, I took the bull by the horns and wrote a letter to the Washington Office strongly recommending increased salaries for rangers who were then receiving but $75 per month and had to furnish their own horse feed. McClure, of course, had recognized that we could not expect to retain good rangers at such a meager wage, but had not submitted any recommendation for increased salaries. In my work, I was naturally closer to the men and knew their problems. There was Ranger Goddard, for example, with a wife and five children to house, clothe and feed, (we had no ranger stations then suitable for use by a family — they were only rough cabins) and also two and three horses to maintain. Their living conditions were far from representing the abundant life.

|

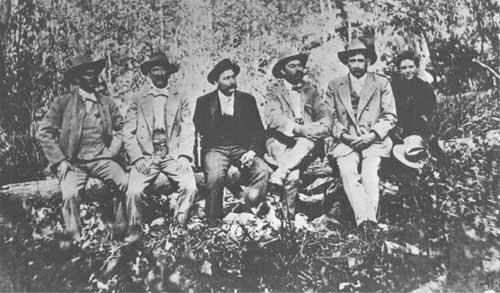

| Figure 3. Gila Supervisor R. C. McClure (center) and Forest Officers on the Reserve in 1903. |

Whether or not my letter brought immediate results, I do not recall; but I have in mind that it was not long before the entrance salary for rangers was raised to $1,000 per year.

Ranger Jack Case, who was somewhat of a wag, had written the following poetry which is quite self-explanatory:

The Ranger's Lament of the Gila Forest Reserve.

The sad October days have come,

And This is a sad, sad day,

For 'twill soon be cold and I do not know

What I've done with my summer's pay.The leaves have turned brown, and come drifting down,

And we now have frost at night,

I must rustle around and get some clothes,

For these khakis are mighty light.My toes stick out on the cold, cold ground,

And it's rather hard on my feet,

But we can't buy clothes with the pay we get,

It's all we can do to eat.

Timber Sale Slash Disposal.

Instructions from the Forester were specific in regard to the disposal of slash resulting from the cutting of timber. Branches and tops were to be lopped and piled compactly in moderate size piles that could later be burned without destroying reproduction or timber. The reason, of course, was to reduce the fire hazard. The rangers and I were able to secure pretty good compliance from our purchasers, but I recall one who thought I was unnecessarily strict and during one of my inspections he suggested that if his brush piles were not wholly satisfactory, about the only thing left for him to do would be to build a little shingle house over each pile.

After several months of experience in the supervision of timber sales in various localities, I decided that there were situations where it would doubtless prove more beneficial to simply lop the branches and scatter them rather than pile them. I felt that such a change should be made in timber occurring on thin scab rock soils, where humus was needed to build it up. The proposal for a change in instructions along these lines was duly presented to the Forester who approved, thus giving discretionary powers to the men in charge of sales.

The Miller Family.

While working on one of our larger timber sales on March 7, 1906, in scaling and marking timber, I found that the whole "damn" Miller family, as they were called, was engaged as help; the mother, daughter and son were felling trees and bucking them into logs, while the "old man" was the bull whacker. All of the members of the family either smoked or chewed tobacco, and I was told that their tobacco bill ran even with their flour bill. They had come out from Indiana in a Studebaker wagon and scarcely knew what it was like to live in a house. They never used a tent, but instead stretched a wagon sheet over some logs or boards. I was told that while the Miller family was over on the "Blue" (Blue River in western Arizona) the Miller family was camped on one side of the stream while another wagon outfit was camped on the other side. Mrs. Miller yelled over and asked how the kids were, and upon being told they were not so well, she asked. "What kind of a wagon do you use?" The other said they used a "Bain." "Well," said Mrs. Miller, "we have found that our kids were always more healthy in a Studebaker."

In the interests of truth in advertising, this yarn was not submitted to the Studebaker Corporation.

Grazing Fees.

When on January 1, 1906, charges for the grazing of livestock on the Forest Reserves were initiated, we realized that our troubles would be increased considerably. To save the stockmen on the north end of the Forest from making a long trip to the Supervisor's headquarters, the Supervisor and I traveled to Alma where we set up a little office in the back end of the store where we met with the cattlemen, many of whom were drunk. McClure did the talking while I was busy writing out the various forms. While we had to take considerable razzing, the affair went off better than we had anticipated. In some cases it was quite difficult to convince the applicants that they were not telling the truth about the number of cattle owned by them. Some who wanted to build up their herd would deliberately claim ownership of more cattle than they actually owned, simply from the standpoint of having more range assigned to them, while the larger owners claimed less cattle than we know they actually owned. Under the circumstances, we did the best we could and I don't think the Government interests suffered.

I had often read stories of the wild west in which cowpunchers would ride their horses into saloons and stores, but here in Alma I actually saw it done. One young puncher who was quite drunk, rode right up to our table in the back of the store, where we passed the time of day and he then turned his horse and rode out. It all added a bit of color to a setting that already was plenty colorful. The saloon remained open all night and there was a hot time in little old Alma.

|

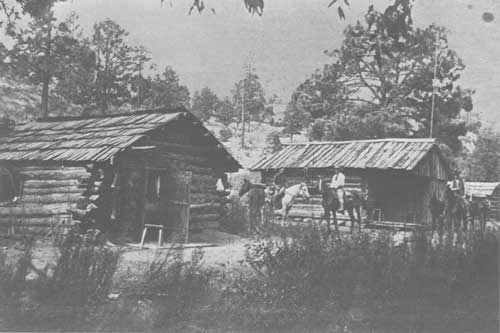

| Figure 4. Old Bear Canyon Ranger Station, Gila National Forest, in 1907. This was not a Forest Service constructed layout but one which in the run of places in those days was found and occupied by Forest officers in lieu of anything else. A Geological Survey crew was camped at the station and the two horses at left belong to that outfit. A Geological Survey man is on the white horse, Ranger Andrews is on the horse at right; the man on the black horse is Douglas Rodman, at that time Forest Supervisor. |

The N Ranch.

I always enjoyed stopping over with Ab Alexander and Shack Simmons at the N Bar ranch. Ab owned cattle and Shack worked for him. They were bachelors and lived very simply. Their log cabin was very comfortable; the meals usually comprising yearling beef cooked in a dutch oven in deep fat, sourdough biscuits, potatoes and thick canned-milk gravy and coffee were just what an outdoor man required and liked, and there was always plenty of horse feed, so I never passed up an opportunity of stopping with them. Besides, they were good company. Ab was quiet and reserved while Shack was inclined to be quite outspoken. His language was most picturesque.

A forest guard had stayed with them at the ranch for a while whom Shack did not like. It seemed that he bragged too much about being a 32nd degree Mason and in other respects showed that he was not the kind of man to be admired by a man of Shack's temperament. So when Shack was later telling me about this guard, whose name has long since been forgotten, he said. "Hell, he hadn't enough brains to grease a gimlet. You can knock the pith out of a horse hair and put his brains in and they would rattle like a peanut in a boxcar."

Forest Service in 1905.

In Secretary James Wilson's report (Report #81) of the work of this department, six pages were devoted to the Forest Service. What a very long way, indeed, we have come since those days. For example, the report pointed out that at the opening of the fiscal year 1905, the employees of the Forest Service numbered 821, of whom 153 were professionally trained foresters, which represented great strides since the establishment of the Division of Forestry on July 1, 1898, when only 11 persons were employed, of whom six filled clerical or other subordinate positions and five belonged to the scientific staff. Of the latter, two were professional foresters.

In these days of controversy as to whether the Forest Service should be transferred to the Department of Interior, it is of particular interest to note what Secretary Wilson wrote in his 1905 report:

Reserve Administration by the Forest Service

The Forest Service has become fully qualified by its past work, for the responsibility laid upon it by the transfer of the reserves to its administrative charge. The administrative effect of the change was the opening of the reserves to much wider use than ever before. This is the natural consequence of entrusting the care of these great forests to the only branch of the Government which has the necessary technical knowledge. The inevitable consequence of a lack of such knowledge must be the restriction of right use or the practical certainty of misuse. Only under expert control can any property yield its best return to the owner, who in this case is the people of the United States.

San Francisco Earthquake.

On the 18th of April 1906, the day this catastrophe occurred. I was on a horseback trip through the back country of the Gila en route to Mogollon, a gold mining camp where there was always considerable timber sale business. Ranches were few and far between in this wilderness country, but by proper planning, one could make a ranch each night. The Reserve had no telephone lines; there was scarcely any money allotted for improvement work in those days but we managed to get along in one way or another. On the 17th I had ridden from Vic Culbertson's GOS ranch on the Sapello to John Converse's XSX ranch on the East Fork of the Gila. Culbertson was our largest cattle permittee and owned about 3,000 cattle. His ranch still stands out in my mind as the most beautiful layout I have ever seen. John Converse, a Princeton man, was the son of the President of the Baldwin Locomotive Company of Philadelphia, and he was enjoying ranch life tremendously. It was always a nice change to stay with him overnight. He also was one of our cattle permittees, so we had business with him from time to time. I recall that he made the first application for a drift fence to be constructed on one side of his allotted range.

It was not until Saturday night, April 21, that I arrived in Mogollon and going immediately to the saloon where one could usually find anybody one was looking for. I heard talk of the earthquake. When I asked. "What earthquake?" I was looked at in amazement and asked where I had been? Mogollon was 90 miles from the railroad at Silver City, and without telephone communications, but there was daily mail service by relayed stages.

Good Advice.

Forest Supervisor McClure may have had his faults like the rest of us, but he also had his good points. One time when all kinds of work was piling up on me and just before starting out on a trip. he gave me this good advice which I have always remembered and also have tried to apply, "Let your head save your heels." To be sure, work plans as we now know them were unthought of in those days. but we did our planning, but not to the extent of spending so much time on it as to interfere with accomplishments, which can sometimes happen under present-day conditions.

Advice of a different character was written in a letter by former Forest Supervisor C. M. Shinn of the Sierra Forest Reserve, California, to Ranger Bert Goddard upon the eve of the latter's promotion to the position of Deputy Forest Supervisor of the Gila Reserve. Coert DuBois had made a thorough inspection of the Gila in the spring of 1907, and had been so impressed with Goddard's qualifications and ability that he had recommended his promotion. This is the part of Mr. Shinn's letter that we considered particularly fine: "The first and last philosophy of life is this, find out once for all that you are neither interesting nor important, but that other people are both; then wear your own self as easily and comfortable as an old shoe, i.e., never think about it; think of the other fellow; think of the Service."

What a world this would be if everybody could live up to this philosophy; Supervisor Shinn was a wonderful man.

Boundary Examinations.

1907 was the year of feverish activity in establishing additional National Forests while President Theodore Roosevelt was still in office and all that was required was a Presidential proclamation. Fast work was required. Boundary examiners assigned to the southwest, W. M. B. Kent (Whiskey Highball, as we called him) and Stanton G. Smith, got in their "good licks" and it has always been amazing to me how well the boundaries were fixed in view of the extensive character of their examinations. To be sure, adjustments were later made in boundaries after the creation of the Forests when it was evident that lands unsuited for National Forest purposes had been included, or on the other hand, lands of value for forest purposes had not been included.

Ranger Examinations.

The first examinations for the position of Forest Ranger under the new regime, were held at various points throughout the West on May 10 and 11, 1906. Supervisor McClure conducted the examination in Silver City, while I was designated as the examiner for Magdalena, at the extreme northeast corner of the Reserve. Only two applicants appeared, one of whom was Frederic Winn, who now holds the position of Supervisor of the Coronado National Forest, Arizona. In those days he was known as the "cowboy artist" around Magdalena. He was a Rutgers College man who had drifted to Texas and New Mexico after graduation for the life of a cowboy.

The first day of the examination comprised a written test. There was one sheet of questions covering practical matters in connection with the work of a ranger, and a second sheet of questions on the "Use Book". (Instructions for forest officers.)

On the second day field tests were held, comprising riding, packing a horse, compass reading, map making, timber cruising and preparation of a statement describing the timber on the area cruised.

Service Orders.

Service Order No. 125 of February 16, 1907 was most important in making the first step toward decentralization. As a result of this new set up, I was assigned to District 3 with headquarters in Albuquerque in June 1907.

Previous to this assignment I had had about a six-weeks' detail in the Washington Office after leaving the Gila Reserve. D. D. Bronson was Chief Inspector while T. S. Woolsey, Jr., and I were his assistants. After several months, W. S. (Bill) Barnes was also assigned to our head-quarters as an inspector. I happened to be "Acting" at the time he breezed in and he introduced himself, saying, "My name's Barnes, what's yours?" He was a great guy!

Then on March 11, 1907, Service Order #126 was issued and how glad we all were to have "National Forest" substituted for "Forest Reserve." It was good psychology to drop "Reserve", which could only mean what we did not want it to mean.

I do not recall when Service Order No. 12 was issued, but it probably caused more discussion among field men than other more important orders. It concerned itself about drinking on the part of forest officers and as I remember contained an admonition or two. All of which was quite right, but the unusual wording used in the order brought on the laugh and comments. We had never seen the word "competent" used as it had been used in a sentence of the Order: "It is not competent for a forest officer, . . .". However, the order was understood and pretty generally followed.

|

Inspection Days.

From June 1907 to December 1908, our life was most hectic. In making inspections of Forests in those days, we followed a very detailed inspections of Forests in those days, we followed a very detailed inspection outline that had been prepared in the Washington Office, which was most inclusive. It was contemplated that every timber sale, grazing allotment, special use permit, claim etc., should be inspected, together with a review of diaries to determine if time was being spent advantageously, and also a check of office procedures, files, etc. Some of our reports were indeed voluminous — 200 to 300 pages. Certain it is, however, when we completed an inspection, we surely had firsthand knowledge of conditions and personnel. I well recall my first real inspection trip, made of the Jemez, Pecos and Taos Forests, which are now known as the Santa Fe and Carson, and comprise all of the mountain country on both sides of the Rio Grande from below Santa Fe to the Colorado line. This inspection required 30 days in the field and about a week in the office going through the files in securing data in preparation for my trip. I covered an estimated 800 miles on horseback, or an average of about 27 miles per day. To go to all of the places necessary and check on the work being done or contemplated required long hours, and it was often necessary to ride well into the night, and also to get on my way very early in the mornings. I practically killed two horses on this trip: the first one was too old and after a couple of weeks I traded him for a 4-year-old mare. When I returned the mare to the owner of the old horse, he was very much pleased about the trade I had made regardless of the fact that the mare was about worn out and "poor as a snake."

After having been accustomed to riding my own horses, it was tough to have to depend on rented horses: the more I saw of rented horses, the more I appreciated and loved the horses I had owned previously.

My longest ride in any one day on this trip covered 60 miles; it was much too far to go in a day, but in the absence of a suitable place to stop over for the night, there seemed to be nothing else to do. High wind and rain storms slowed us up and made riding disagreeable, while swarms of flying ants made life miserable while they lasted. I soon learned that I had made a mistake in waving my hat to keep them away from my face: they got into my hair and it was difficult to extricate them. Fortunately when the rain came, the ants left.

To reach Antonito, Colorado, which was my destination, the road traversed a low country that had been pretty well flooded by the heavy rains during the day. I struck this boggy section of the road after dark when my horse was so tired he could scarcely make headway on firm ground. After much floundering about, we managed to get through and at about 10 o'clock, I reached Antonito and most anxious to get some nourishment, since I had had only one sandwich since breakfast which I had eaten about 5 a.m. But much to my dismay, the stores and restaurants were closed, and the small hotel had no dining service. So there was nothing to do but go to bed hungry but I was too dog tired and sleepy to let this bother me unduly.

Ross McMillan was Forest Supervisor at this time, having succeeded Leon F. Kneipp, who had been transferred to the Division of Grazing in the Washington Office.

Several days before the close of my inspection trip, I reached the Dye timber sale and there met Supervisor McMillan and his party, which comprised Mrs. McMillan, Inspector Tom Sherrard, who was then in charge of timber sales in the Washington Office, his cousin Margaret Lewis, from New Haven, and her friend Miss Drew Bennett, of Phoenix, Arizona, to whom Sherrard was then engaged, and two rangers who acted as guides and packers. The party had covered portions of the territory traversed by me, and had ridden about 400 miles. I remember that Tom and I spent a day on inspection of the Dye sale and had a friendly argument about proper methods of marking timber for cutting. After all of these years, such arguments continue.

|

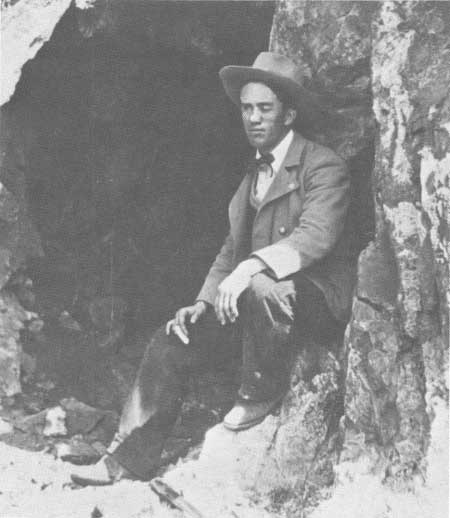

| Figure 5. Supervisor McGlone, Chiricahua N.F., at the entrance to a forest cave, 1904. Photo by L. A. Barrett. |

Moldy Bread and Moldy Ham

I believe it was in November 1907 when the headquarters of the Chiricahua Forest was transferred from Paradise, a small mining camp in the mountains, to Douglas, Arizona, a copper smelting town on the Arizona-Mexico border. A left-over from the Interior Department by the name of McGlone was the Forest Supervisor. He was a misfit and an inspection made by me proved conclusively that he was almost a total loss in the position he held.

I happened along later in the same month and with McGlone, we took the mail stage from Douglas to Paradise. When we approached the post office and general merchandise store, on the porch of which there were a number of loiterers, we were greeted with a yell that went like this. "Moldy bread and moldy hams — to hell with the Forest Service," followed by the typical cowpuncher yell. This was a bit disconcerting to say the least, and after we had reached the place where we were to stay overnight, I learned upon inquiry from McGlone the significance of this most unusual greeting.

It seems that after he had moved his office to Douglas he had been interviewed by a newspaper reporter who had been interested in learning the reasons for transferring the headquarters. After stating the principal reasons, he went on with disparaging remarks about living conditions in Paradise, particularly the poor food that one had to put up with and made reference to moldy bread and moldy ham. Being quite naive and not having had experience with reporters, he did not realize that his remarks might appear in bold type in the newspaper. So naturally when the residents of Paradise read the paper and saw what McGlone had said (unfortunately the article gave the impression that the compelling reasons for the transfer were due to the poor food he was able to get in Paradise mentioning specifically the moldy bread and ham), they were incensed to a fighting degree.

McGlone never lived down this indiscretion. and it was not very long before he was shelved. While his lack of tack as shown in this incident was a contributing factor in his removal, inspection had shown conclusively that he was not qualified for the position of Forest Supervisor and that his services were far from efficient.

Special Inspections.

Besides making very intensive inspections of all activities of a Forest, we were often called on to go out as "trouble shooters." The Forest Service had employed an engineer to make an accurate survey of the boundaries of one of the old Spanish land grants within the Jemez National Forest. As I recall the case now, the engineer, whose name was Bassett, was drinking to excess and something was rotten in the financial management of the camp. At any rate I was assigned to make the necessary investigation. The trip that I had to make on horseback after leaving Espanola, the railroad point, is herewith quoted from my diary:

January 2, 1908. At Espanola; arose at 6:30 a.m., by 7:10 I was in the saddle, and it was awfully cold. My pony which I had procured from Ranger Lease was all bowed up, but I held his head up and kept him from "piling" me. About 3 miles from town up the Rio Grande valley, I met Ramon Salazar, a butcher, and another Mexican. who were going to Canones, which I was told was close to Coyote, my destination. We didn't go by the regular road up the Chains River by way of Abiquiu but took a more direct route by road and trail across the mountains. I later regretted not taking the regular road, for we got into snow and had to follow icy and rocky trails for miles. I became awfully sore since the saddle did not fit me. (It was not long after this trip that I decided to use a McClellan saddle instead of depending on any kind of a saddle I was able to rent. Having always used a large stock saddle. as did everybody else, I had to take some "razzing" when I changed to a McClellan. One can, of course, get saddle sore from riding a McClellan, but not nearly so sore as riding a misfit stock saddle. I still stick to the McClellan for the relatively limited riding I now do.)

Rode like the devil when we came to fairly level stretches. Stopped at Juan Lopez's goat ranch on the Lobato Grant for dinner and also fed our horses. For our dinner we had boiled potatoes with meat, tortillas, and coffee. Since the only dishes that were set before us consisted of a cup, saucer and spoon, I ate the potatoes with a spoon and picked the meat off the bones with my fingers. We paid $.50 for the meal.

The Mexicans I was riding with talked their lingo all day long and only occasionally spoke to me in English. After going down a steep-sided rocky canyon for about 3 miles, where the trail was fierce, we struck Canones, a small plaza, about 3:45 p.m. My compadres left me at about 4 o'clock at a ranch where they were going to buy cattle to drive back to Espanola, and I started for Coyote, 12 miles further west. It was quite gloomy at 4 o'clock because of the black snow clouds. My poor little pony was about all in, but when a Mexican caught up with me about dark my pony took a last brace and stayed up. An incident of the last stretch was when I saw a coyote about 50 yards off the road which stared at me and refused to move notwithstanding my shouts and gestures.

Reached Coyote about 6:15 after having crossed the icy Rio Puerco numerous times. It was plumb dark. I went to the pool room and found a boy who took me to Garcias' where I found a pretty squalid outfit. Only the son could speak English; he had been attending the Phoenix Indian School for three years. Had a supper of eggs, steak and coffee, all the while the whole family standing about and talking about me. I later learned I was the only white man (American) in town. After supper I went to my room where a blazing fire in the three-cornered fireplace was burning chee fully. Talked with Garcias' English-speaking son until bedtime. Feeling better but ached all over. My horse had been well taken care of. I slept quite well.

Sunday. January 3, 1908. Arose at 7:45 a.m. Had a greasy breakfast of fried potatoes, frijoles, an egg and coffee. Many Mexicans in town; church bells ringing all the time. Can scarcely walk owing to swelling of my legs from riding. Dread getting in saddle again. It is snowing, but not enough to bother. Being only white man in this placita, I feel as if I were in a foreign country. Everybody stares at me. Got my horse from the corral at 11:30, paid bills and started up the canyon for Ranger Blake's headquarters.

Stopped at the second adobe house where I had been told Blake made his headquarters. On knocking, door was opened by a six-year-old boy and looking in the room, I saw an old decrepit man (Max) sitting on the floor alongside of the fireplace. I asked him in Spanish if Blake lived here and he yelled out something which I did not sabe. Then he got up and I saw he was terribly deformed and also blind. He staggered to me and I allowed him to shake hands with me, but when he commenced rubbing his hands on my arm and I got a good look at his face which was most hideous. I concluded to "hit the adobe" for I had a hunch he might be a leper or had some equally terrible disease. I then rode to the next house which proved to be where Blake was living and his Mexican friends informed me that he was about 6 miles up the canyon working on a cabin.

I rode up over the slippery, hilly road, met Blake and after getting warm at a camp fire, returned with Blake to his house. It snowed all afternoon. Assistant Ranger Crumb came in the evening and I was glad to see him for it saved me a considerable ride. Had a bum supper cooked by Mexican woman. Blake turned in about 7:30 p.m. Crumb and I discussed the Bassett affair and I had him write a statement regarding it. We tuned in about 11 o'clock. At 1 a.m. Blake got up and rummaged about the room, rustling papers, going through trunks and boxes. At 4 o'clock he called Crumb and me to get up for breakfast. At 5 o'clock Blake was in the saddle, while I waited for daylight before starting out. (Blake must have had a bad conscience. He was a hard looking individual and certainly no credit to the Forest Service. I had learned before meeting him that he had been involved in cattle rustling several years before; he looked mean enough for playing that kind of a role. He was respected or, probably it would be more correct to say, feared, by the Mexican population of his district. As I remember, Blake's period of employment was rather short. Men of his type may have served a purpose for a while, but they were totally unfitted for continued employment.)

January 4. Rode from Blake's headquarters on Coyote Creek to Abiquiu. About 3 miles from Coyote I got on wrong road which took me too far to the northwest, so I cut across a big open country to strike the right road. The coyotes were numerous and barked at me. My pony wanted to take me back to Coyote and it was necessary to fight him to keep him headed the way I wanted to go. It was long wearisome ride down the Chains to Abiquiu. My legs ached so badly I could not stand riding out of a walk. Crossed river to Abiquiu intending to stay at Tomas Gonzales' but he was not home, so I crossed back and after much inquiry, found a stopping place at Jesus Martinez's adobe 3 miles below Abiquiu. Never saw so many nasty Mexican dogs as there in and near Abiquiu. They came at us in bunches, snarling and biting at my horse's heels. At Martinez's the daughter who had attended a Presbyterian mission school could speak English fairly well.

A trip to Showlow.

In March 1908, which is always a blustery month in the Southwest. I had to go to Springerville, Arizona, the headquarters of the Black Mesa (now Apache Forest) for the purpose of assisting Supervisor Martin in a reorganization of his office, or to get order out of chaos. Martin had been a fairly good ranger but as a Supervisor, left much to be desired. He was conscientious and tried hard, but he simply lacked the educational background for a supervisorship. I had made a trip to Springerville in October 1907 so I knew what to expect.

One got off the Santa Fe train at Holbrook about 4:30 in the morning and then waited for the mail stage, a buckboard driven by two horses. The first day one traveled 35 miles to Hunt, which comprised but one house and there one stayed with a Mormon family. The next morning, at 5:30 another stage outfit with a hairy old Mormon as driver, took you 25 miles to St. Johns, a sure enough Mormon settlement with lombardy poplar trees growing along the irrigation ditches. Here you were transferred to a homemade two-wheel cart drawn by a mule, and rode 35 miles over the rocky, hilly roads cramped up in a manner that was not conducive to a pleasant disposition. On my first trip I asked the Mexican driver of the two-wheel cart if the hotel in Springerville was run by Mormons to which he replied, "No, Americans run it."

After about a week's work with Supervisor Martin, I started out early one morning for Showlow, the headquarters of the Sitgreaves Forest. While the distance was 50 miles, I was able to rent a fine "up and coming" horse, so thought I should have no difficulty in reaching Showlow by dark. But the day turned out to be pretty bad, high winds and snow storms, and muddy roads. I was in the saddle 13-1/2 hours; no, it was probably 12 hours, for I had to walk and lead my horse as he had gone lame in one foot and was about to give out.

At 10 p.m. I decided it was impracticable to attempt going further, so I made camp on a gently rolling ridge on which there was a scattering of pine trees. First, I gathered needles and twigs and built a small fire and then rustled around in the darkness for some good size chunks for making a big fire, since the night was cold and windy. All I could find was a rather large log and not having an axe, I had to exert all of the strength still left in me to drag it in.

After unsaddling and feeding my horse — luckily I had brought a feed of oats on my saddle — I tied him up and then started out afoot to reconnoiter. I felt quite positive that I was on the right trail and also that I must have covered about 50 miles and should therefore be somewhere in the vicinity of Showlow. However, after scouting about for an hour or so, I returned to my camp, hobbled my horse, laid my saddle blanket on some pine needles which I had scraped together to soften the malapais rocks a bit, sat down before the fire to think it over. It was surely a lonesome night and while I managed to doze a little, I couldn't sleep. A bunch of coyotes prowling about would howl heathenishly and make one feel a bit shivery. I had a sandwich in my saddle bags which I had saved out from my lunch but refrained from eating, believing that I would be more hungry in the morning. And besides, if my horse got away from me during the night, I figured it wouldn't be so good to be afoot and perhaps lost and with no food whatever.

Along about 2:30 a.m. I was dreamily thinking of the good bed I was missing and many other things when I realized that I could not hear my horse. Immediately I aroused myself and started out to find him, and much to my surprise, for I had thought he was about worn out, I found him about 3/4 of a mile from camp and making hurried tracks to Springerville. I brought him back to camp, tied him up and let him feed on "post" hay for the remainder of the night. He was really good company for me and I was amused in watching him for he seemed to have me sized up for somewhat of an idiot and by his looks, I imagined he was rather sneering at me. I couldn't blame him a bit.

Although there were no people living between Springerville and Showlow, there was an old deserted house situated about half way where I could have camped, but at that time I had an idea that I could make it easily into Showlow by at least 8 o'clock.

Daylight came none too soon to suit me. I prepared a hurried breakfast, which consisted of a toasted tongue sandwich, then I saddled up and started. After riding two miles, I found myself in Showlow. I had been on the hill above Showlow when I was out reconnoitering and could have seen the town if there had been any lights in any of the houses. The Mormons had the habit of going to bed early. I had arrived at Supervisor Mackay's headquarters just in time for breakfast, immediately after which I went to bed and slept until 3 o'clock.

I stayed in Showlow two days and then hit the trail back to Springerville, but this time I made a two-days' trip of it, because a ranger with a pack outfit came half way with me and we camped in comfort.

To the Roosevelt Dam.

My first trip to this dam was during the period of its construction in June 1908. The Government had built a fine road, certainly the best road in the Southwest at that time, from Mesa (near Phoenix) to Roosevelt, a distance of 60 miles. The road was required for the transportation of construction materials for the dam. Many freighters with their 8 to 16 horse or mule teams were on the road. My trip was made in a Concord stage (leather springs) which was drawn by four horses. Horses were changed four times during the trip so twenty horses were required for the trip which was made in a day. For the first 18 miles the road traversed the level desert country where the giant cacti grow; then through foothills country for about 30 miles and then into the mountain country. The road has splendid grades and a good surface. Fish Creek hill was the real scenic spot along the road. Here the road was made by blasting down solid rock walls. Approaching the highest turn on this hill, the stage driver hit up his horses taking it on a high gallop. While there were passengers inside of the stage, I sat on the high seat alongside the driver. It was surely a real thrill when we were rounding this high point on the curve and I could look down over the sheer cliff which was about 500 feet.

The dam itself was a most impressive sight in those days. The extreme heat at the dam was most enervating. Even in the Supervisor's office — Roosevelt was the headquarters of the Tonto Forest and the office was in one of the Reclamation Service buildings — during the week I stayed there the temperature reached 105 degrees every afternoon except two when it registered 113 degrees.

Supervisor W. H. Reed was the sickest man I had ever seen working. He was suffering intensely from an acute form of asthma. Every night he had spells during which he coughed terribly. There was a peculiar rattle in his throat while he was left gasping for breath. He was unable to lie in bed so sat up nights in a chair in reclining position. How he accomplished his work and so much of it under these adverse conditions was amazing. His wife who had an appointment as clerk in his office was a wonderful help. It was necessary for him to give up his position a year or so later; he and his wife moved to sea level in California where his condition became somewhat improved, but it was not long before he passed away. He was a wonderful man and gave the Forest Service everything he had, under conditions which scarcely could have been more trying.

|

| Figure 6. Tonto Supervisor's Cottage at Roosevelt, Gila County, Arizona, May 27, 1913. |

Ranger Training School.

The first real school for the training of forest rangers was held in a camp at Fort Valley in the Coconino Forest in September and October 1909. Previously training of a kind was given in ranger meetings held on the various forests that were attended by chiefs of the various divisions and sometimes by men from the Washington Office. I recall the first series of such meetings held in the early spring of 1908 before the creation of the Districts as administrative units. In addition to the local forest forces, the inspection office personnel comprising D. D. Bronson, T. S. Woolsey, Jr., and myself; Geo. H. Cecil then assigned to Operation in Washington and Arthur Ringland who was also then assigned to the Washington Office, attended

Such meetings were necessarily confined to a discussion of existing problems and procedures. They served a valuable purpose. At the Fort Valley ranger school, however, the idea was to teach techniques by actual doing. For the first month I was the director and camp manager. I still have occasion to often think about this camp of long ago, for when I left the boys presented me with a fine large Navajo blanket and an Apache Indian basket both of which have been in continuous use ever since.

For the second month Allen S. Peck (now Regional Forester at Denver) was the director.

* * * * * * * * * *

From the Use Book of 1906, page 151, "In order to give the rangers the benefit of each other's experience, to keep them in touch with the entire work of the Reserve, and to promote esprit de Corps in the Service, a general meeting of the entire force on each Reserve should be held annually."

* * * * * * * * * *

Bernhard Rechnagel (Cornell Forest School) and J. H. Allison (University of Minnesota Forest School) were resident instructors, while other instructors came from Albuquerque from time to time to give their courses.

Mr. Pinchot had taken a great interest in this school and had sent out a trophy to be given to the ranger who in competition proved to be the best rifle shot! Certainly, we all appreciated this splendid gesture.

Civil Service Commissioner McIlhenny, who was a close friend of President Roosevelt, visited the training camp for the purpose of securing first-hand information about the work of forest rangers, and to see the type of men we were getting for that position. He had been in command of one of Teddy's Rough Rider regiments. A couple of years previously, President Roosevelt was his guest in Louisiana when he (Roosevelt) was on a bear hunt, and President Taft expected to end up his western trip there. I was told by McIlhenny that he raised the only perique [a particularly rich tobacco] that was grown in the U. S. on his estate in Louisiana.

We had fully intended to conduct the school each year, but our plans were upset upon receiving a legal opinion to the effect that the Forest Service appropriations could not be used legally for such purposes. So that was that, and ranger meetings became popular again.

|

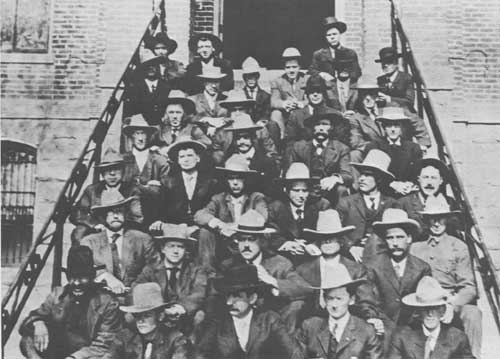

| Figure 7. The combined Gila (S), Gila (N), and Datil Ranger Meeting at Silver City, NM; May 1908. |

Uniforms.

The subject of uniforms for forest officers has always been a live one in the Service. Whenever one wished to get a real argument going at a ranger meeting, all that was necessary was to start talking about uniforms. The usual field clothing of rangers during the 1905 - 06 period comprised a pair of blue overalls ("Levi Strausses", as they were called), a work shirt of any kind, and a short blue denim jumper, topped off with a wide-brimmed sombrero (Stetson). In addition to this outfit, the rangers in the Southwest packed six-shooters, and wore "chaps", especially in brushy country or when the weather was bad.

While still at New Haven, I had made a very attractive riding suit of brown flecked corduroy. I realized immediately after noting the characteristic dress of the he-men of the Southwest, that my riding clothes were quite out of keeping and would make me entirely too conspicuous. While I didn't go so far as to adopt the Levi Strausses, I did use khaki trousers for about the first season, and subsequently khaki riding breeches, and while I found the latter much more comfortable for riding and just as comfortable as trousers for walking provided they were not too tight in the knees, I must admit that considerable intestinal fortitude was required to wear them. However, I had a little support due to the fact that we had some ranchers from the east who on occasions wore riding breeches and then there were several English "remittance" men who sometimes wore "choke bores" as they were called by the rangers and cowhands, but for the most part they were so anxious to "do as the Romans do" that they wore the most disreputable looking clothes they could find and largely forgot about their "bawths." It was always a matter of wonderment to me how these supposed wellbred Englishmen could go from one extreme to another in so short a time. I recall one Englishman by the name of Montague Stevens, a very well educated man, although somewhat eccentric, who allowed his standard of living to drop so low that he did not object to the chickens coming in the house and when at table, one had to shoo the cats from his plate if one expected to eat anything.

Many were the arguments I had with the rangers regarding the superiority of riding breeches, but I knew they would not be convinced unless they actually gave them a trial. After Ranger Bert Goddard, who had been a top cowhand, bought a pair and liked them, others followed suit. But as long as I was assigned to the Gila, choke bores were anathema to the resident stockmen and cowpunchers.

I believe it was early in 1908 that the first Forest Service uniform was adopted. I've quite forgotten who was mostly responsible for its design, but at any rate, the German foresters uniform was aped in certain particulars, especially the high, tight-fitting collar. It was not long before it was called the "German Crown Prince" uniform, but by reason of the poor fittings we were able to get by mail order purchases, some of the men wearing them looked more like pictures of German soldier prisoners during the World War.

At some hotels the bellboys were wearing uniforms of about the same design and color. Arthur Ringland, who was short of stature and rather boyish looking, was made painfully aware of this when we were staying at the Gadsden Hotel in Douglas, Arizona, at the time we were having a ranger meeting there in 1908. Ringland had his uniform on and was walking bareheaded across the lobby when a guest approached him with a letter, saying, "Boy, mail this letter." Ringland, who was always a strong advocate of uniform clothing for forest officers, did not allow his enthusiasm to be dampened by this incident, but for a time his face was red and of course the story went the rounds.

The purchase and wearing of the uniform was not compulsory, so there never was anything uniform about the dress of forest officers, except possibly at ranger meetings when at least those who had bought uniforms would wear them. They figured if they did not wear them on such occasions, they would never have the opportunity of wearing them at all. So the discussions and arguments about uniforms continued year after year, but not until recent years was a regulation promulgated for the compulsory wearing of standard field clothing. For many it was a sad day when they have to give up the wearing of their Stetson sombrero. Having had my fling with this type of hat for years, I personally had no objection to the changed type which is really a more comfortable hat for general wear. In the horseback days, however, I am thankful that sombreros were recognized as the hat the well dressed forest officer should wear. As a memento of those days, I still have the Mexican hand-carved leather hat band which I used to make my hat, shall I say, somewhat distinctive?

The World War had its influence on the design of the Forest Service uniform. I had been assigned as inspector in the Division of Operation in the Washington Office during the War in 1918, and was designated by Mr. Graves as a committee of one to design a new uniform. From the English army officer's uniform the open collar and large bellows pockets furnished ideas. The arrangement of pockets, however, was changed and a sewed on belt added. This style was effective until about 1934 when a Service-wide committee designed the present day uniform, which retains the best features of the one I had designed and unfortunately some that are no longer considered so good.

The subject of uniform field clothing for forest officers will always afford much discussion, but certainly far less than in the early days.

|

| Figure 8. Heinie Marker: timber beast about 1924, dressed in his "choke bores," at Deer Springs Lookout tower. From the Paul Roberts photo album. |

Act of June 11, 1906.

This Act providing for the homesteading of National Forest lands which had been classified as chiefly valuable for agriculture, was doubtless a necessary evil. It resulted in no end of work and grief and in later years, it seemed quite ironical for the Government to buy back lands which had been patented under this Act.

During the inspection district days, 1907 and 1908, the inspection offices were the clearing houses for this work and all reports from examiners on applications for lands were reviewed here before being submitted to the Washington Office. Shortly after we got into this work it was found that there was considerable lag on some of the Forests largely because qualified personnel was not available. I remember that I spent considerable time on several Forests in Arizona in the examination of applications on the ground. To speed up the work I had Ranger Powers of the Coconino to assist me; he had been trained as a surveyor and was a good draftsman. Every night after a full day's work we would work up our notes; Powers would make the map while I would prepare the report.

Practically all of the lands applied for were narrow benches along creeks, "shoestring" ranches, as we called them. It was very seldom that we were able to recommend as much land as had been applied for. These small farms were suitable for stockmen's headquarters, but for straight farming without stock, they would not provide a living. In this present age, such lands are classed as submarginal.

In the Arkansas Forests, real estate men created a boom and had a regular racket in getting people to make applications for homesteads. The Service had to make more concessions in Arkansas than was necessary in either New Mexico or Arizona. It was considered that if this were not done, there was grave danger of political pressure to abolish the Forest. I later learned that similar pressure was exerted for allowing claims within the Siuslaw National Forest in Oregon, comprising lands that were clearly more valuable for growing timber. The following letter is fairly typical of complaints received from prospective settlers in Arkansas:

|

On the Forests where examinations were made by me, I made it a point to recommend the withdrawal from entry of suitable lands for administrative sites — ranger stations. To be sure, no one could foresee how many of these sites would actually be needed in the years to come but we considered it much better business to recommend for withdrawal just as many sites as we could reasonably defend.

One now hears and reads much about the evils of soil erosion. I had seen so much serious erosion in the Gila Country due to cloudbursts and overgrazing that I had somewhat of a background for recommending disapproval of many applications covering lands which it was believed would wash away if cultivated.

The "Act of June 11" period in this Service was a most interesting phase, regardless of the fact that the Act was ill conceived. The Government is still paying the penalty for the errors made by reason of this legislation. Unfortunately, support for the National Forest enterprise was far from general during the first decade of Forest Service administration.

|

[The following pages contain the complete text of "Instructions to Inspectors," the detailed instructions for implementation of Service Order No. 125. In the original document, Section X was omitted: the next letter, dated September 27, 1907, corrects that error.]

Duties

It is the duty of Inspectors:

1. To assist, advise, and encourage forest officers in their work.

2. To examine conditions on the ground, and report what they find.

3. To recommend changes for the better.

Before an inspection is made, the Chief Inspector should carefully instruct the Inspector who is to do the work. He may be instructed to cover all the business of a National Forest, both administrative and technical, or only one or several parts of the business. Work upon the ground should be exceedingly thorough, and should in every case made it possible to present to the Forester:

1. A definite statement of the actual conditions found.

2. Definite recommendations for action.

The Inspector should be absolutely sure of all facts reported. If he reports a thing to be so, the Forester assumes that it is so, unless new and conclusive evidence to the contrary is introduced.

The Inspector's recommendations should be specific and clearcut. A statement of facts which calls for action should never be followed by indecisive recommendations, nor should the Inspector, having stated the facts, leave the Forester to draw his own conclusions. Inference, opinions, and hearsay should be given as such; definite statements must be susceptible of proof; serious charges should be supported by affidavits when necessary.

Inspectors should never forget that a most important part of their duty is to assist and encourage forest officers in every possible way. They should not inform a forest officer that his work is unsatisfactory in any respect without advising him how to improve it. They should use every opportunity to imbue forest officers with a spirit of pride in their duties, and in their contact with the public they should endeavor to increase understanding of the work and aims of the Service.

All Inspectors should keep a careful diary of their movements and work. They should also examine, sign, and report upon the diaries of all forest officers whose work they inspect.

Reports

1. Reports should be direct, concise, and dignified. The conditions found should be first described; if they are bad it should be plainly stated why they are bad, and definite recommendations made how to set them right. When a point is once under discussion, it should be carried through to an end and then dropped.

2. All inspection reports should be addressed to the Forester and submitted through the Chief Inspector, by whom they will be approved, commented upon if necessary, and forwarded to Washington. All other communications to the Forester, whether relating to inspection or routine matters (including accounts and supplies), should also be submitted through the Chief Inspector; except that, in cases of emergency, Inspectors may communicate direct with the Forester, notifying the Chief Inspector of their action.

3. All reports and correspondence from District Inspectors addressed to Washington should be forwarded in envelopes marked "Inspection."

4. All inspection reports and letters relating to inspection should be submitted to Washington in duplicate (original and one carbon). Inspectors should prepare their reports in triplicate, so that the Chief Inspector may retain one copy for the files of his office.

5. All reports should be submitted in sections, as indicated below, and each section should begin a new page. For convenience in filing, the discussion of each case (including trespasses) in Timber Sales, Grazing, Claims, and Uses, should also begin a new page. The pages of each section of the original copy should be temporarily clipped together, not permanently fastened, nor should the original copy be permanently fastened together as a whole. All the pages of the duplicate copy should be permanently fastened as a whole. The first page of each section should be headed with the name of the National Forest, the name of the writer, and the date of the report.

6. Separate and definite recommendations covering each subject discussed (if action is called for) should be made at the end of each section, and should be numbered. When a subject is discussed by cases, the recommendations should come at the end of each case. In the case of both good and bad work found, the names of the forest officers responsible for it should be stated.

7. The Inspector making the report should sign each section of the original, and each section should be signed by the Chief Inspector, if he approves it. In case of disagreement. a memorandum should be attached, in accordance with Service Order No. 125.

8. The Forester will decide whether all, a part, or none of the report should be submitted to the Supervisor, and the Inspector should express his views upon this point in his letter of transmittal.

If there is nothing to report under any of the following sections, it should be so stated, under the appropriate heading.

Legal matters should be dealt with in the section treating of the business concerning which the legal question arose.

SECTION I -- TIMBER SALES

Sales

Begin the discussion of each sale on a new sheet.

1. A discussion of each sale made or continued since the last inspection, covering the following points, with recommendations for action needed:

(a) Advisability of the sale silviculturally.

(b) Policy of making the sale, in view of present and future demand for timber.

(c) Arrangement of the sale; location of cutting area, mapping and estimating, stumpage price, and other conditions of the contract.

(d) Conduct of the sale; marking, utilization, damage to young growth, prospect of reproduction, scaling, disposal of brush.

2. Future timber sale work. Tracts which should be examined. Policy to be followed in arranging sales in different districts.

3. General recommendations for future sales, referring when possible to sales previously discussed for illustrations of methods to be followed or discouraged; prices, and methods of cutting.

4. Recommendations for granting or refusing authority to make Class A timber sales to each forest officer under the Supervisor.

5. Recommendations for increasing or decreasing the amount of timber which the Supervisor is authorized to sell in Class B sales.

Trespass

Begin the discussion of each case on a new sheet.

1. A discussion of each case handled since the last inspection, including:

(a) Policy of considering the cutting a trespass.

(b) Treatment of case by the forest officers; seizure, scaling, efforts to secure settlement.

(c) Condition of cut-over area; whether sales should be made to put the area in proper shape, or applications be refused to give the forest a chance to recover.

(d) Recommendations for action in the case.

2. General discussion, referring to cases discussed for illustrations, when possible. Efficiency of methods in preventing further trespass. Local feeling resulting from cases taken up. Recommendations for preventing trespass in the future.

Timber Settlement

Begin the discussion of each case on a new sheet.

1. A discussion of each case handled or continued since the last inspection, including:

(a) Arrangement of the case; mapping and estimating, stumpage, and forest officer's recommendations for payments on basis of estimate or after scaling.

(b) Conduct of case; supervision of cutting, scaling, and brush disposal.

2. Policy to be followed in future timber settlements, with illustrations from previous cases, when possible.

Free Use

Begin the discussion of each case on a new sheet.

1. A discussion of each free use case of sufficient importance to warrant it, covering the same points as in sales.

2. Free use policy for the Forest. Location of free use tracts. Practicability of scaling or measuring free use material. Granting of green and dead timber for various uses. Classes of persons entitled to free use.

Reconnaissance

1. When obtained incidentally, a rough estimate of the stand of green and dead timber on the Forest or on any division, by species, when possible.

SECTION II — SILVICS

Begin each description on a new sheet.

1. A discussion of the condition of each cut-over area visited to be identified by the timber sale, trespass, or free use case under which the cutting was done. Special trips to secure this information should not be made.

2. Recommendations for special study of silvical problems.

SECTION III — EXTENSION

Nursery Work

Ranger's Nurseries

Inspection reports should cover the following points for each Ranger's nursery:

1. What is the location ad size?

2. Are the seedbeds arranged to the best advantage?

3. Have the beds been shaded properly?

4. Is there a full stand of seedlings? If not, why?

5. Have the plants received proper irrigation and cultivation? Are wrong methods in use?

6. Has there been loss of seedlings from diseases?

7. At what age is the stock transplanted, and are thrifty trees being developed?

8. What improvements do you suggest? Should the nursery be continued in its present size, enlarged, or abandoned?

Planting Stations

The following points should be covered in inspection reports on planting stations:

1. Water Systems. — Is the water system adequate, or should it be improved?

2. Shade frames. — Is the system of shading adequate and satisfactory? If not, what changes are recommended?

3, Seedbeds. — Are the seedbeds well prepared, cultivated, and irrigated?

4. Seedlings end transplants. — Is the nursery producing its maximum quantity of plants? If not, state the cause of failure, which may be due to:

(a) Waste of space through improper arrangement of seedbeds, seed drills, or transplant rows.

(b) Inferior seed.

(c) Insufficient amount of seed sown.

(d) Loss by fungus diseases or destruction by birds and rodents.

(e) Insufficient or excessive irrigation. Is the seedbed in right proportion to the transplant area?

5. Do you recommend extending or limiting the present size of the nursery?

6. Do you consider that sufficient experiments are being carried on to determine the best methods of nursery practice and field planting? If not, what additional experiments should be planned?

Field Planting

It is especially desirable that field planting be inspected both during the progress of the work and later to determine its results. The following phases of the work should be considered:

Handling Plant Material

At the nursery. — Is the plant material properly and economically removed from the nursery?

Is it properly packed for transfer to the permanent planting site?

Is any provision made for storing plant material to retard growth if weather conditions are unfavorable at the beginning of the planting season?

In the field. — What protection are the trees given after being taken to the planting site and before they are set out?

Are changes in methods advisable?

Methods of Planting

What methods are in use? Are these adequate to insure success and carry out the work as economically as conditions warrant? What changes do you recommend?

Are the plating crews organized to the best advantage?

Results of Planting

What percentage of trees per acre have survived under different methods used and at different seasons?

By observation of the results, do you recommend the use of younger trees or older trees, the use of seedlings or transplants, of the species now in use?

What other species would you recommend for trial?

Experimental Planting

Plant material is distributed to Supervisors of National Forests where planting stations have not been established, so as to test species under new conditions and to determine the possibilities of forest planting. Inspectors should report the results of such experimental planting under the heads given under "Field Planting."

As a basis for reconnaissance and experimental planting it is very desirable that Inspectors report whenever it is possible concerning land requiring forest planting within National Forests, covering the following heads:

1. Approximate area and condition of cover on watersheds directly controlling streams from which adjacent towns and cities obtain their water supply, and those which are the source of streams of value for irrigation purposes, or both.

2. Approximate area and condition of cover on denuded land not of immediate importance for the control of stream flow, but which should be planted with forest trees for the production of commercial timber to meet future local needs.

SECTION IV — GRAZING

1. Condition of range; quality of forage.

2. Gazing districts; division of range between cattle and sheep.

3. Grazing periods and fees.

4. Methods of handling stock; salting. etc.

5. Range improvements; fences, corrals, reservoirs, etc.

6. Allotment of grazing privileges: complaints.

7. Grazing trespass. Begin each case on a new sheet.

8. Other matters connected with the livestock business.

SECTION V — CLAIMS

Begin each case on a new page.

1. A discussion of each case reported upon by the Supervisor. Mention should be made of the cooperation between Land Office officials and forest officers.

2. A general discussion of the approximate number, location, and character of claims not as yet reported by the Supervisor, with special reference to their validity and their effect upon the management of the Forest. Recommendations should be given for any necessary examinations and reports, with a view to action.

SECTION VI — USES

Begin each case on a new page.

1. A discussion of each case of occupancy, except sawmills or right of way, granted by the State, by the Department of the Interior, or by the Forest Service. This includes permits for pastures and wild hay.

2. A discussion of each privilege trespass case.

3. A discussion of the general working of the privilege business, as above defined. The utilization of all resources of the National Forests other than timber and forage; the promptness with which applications are handled; the extent to which unnecessary burdens, formalities, or delays are imposed upon applicants, with definite recommendations for betterment of prevailing condition.

SECTION VII -- PRODUCTS

1. Purposes for which the leading timbers are used, and local prices of forest products.

2. Location of treating plants and other establishments of importance.

3. Recommended tests to determine strength, or method of preservative treatment.

SECTION VIII — BOUNDARIES

1. Additions and eliminations.

Definite recommendations should be made for action or examination. If action is recommended, type and title maps should be submitted showing the proposed boundary, with a full description of the country and a discussion of conditions, in accordance with the instructions to Forest Boundary men, a copy of which is attached.

2. Agricultural land.

If examination and reports are made on lands applied for listing under the Act of June 11, 1906, they should be submitted in accordance with instructions to Forest Boundary men on his subject.

If agricultural land is discovered which is not applied for, recommendations for action should be submitted, accompanied by type maps; or a recommendation may be made to the effect that the land should be examined by Forest Boundary men, or the local force.

Discuss in detail the manner in which examinations have been conducted. the general outcome of the work, and the effect it has had on local public sentiment.

3. Ranger stations.