|

Jemez Mountains Railroads, Santa Fe National Forest, New Mexico

|

|

SANTA FE NORTHWESTERN RAILWAY

The Cañon de San Diego Land Grant

The great Jemez caldera is the immense crater of an ancient volcano. Its once towering sides have slumped and eroded through the ages into a terrain of rounded mountains and high mesas, slashed by deep canyons in the volcanic tuff. Heavy pine and fir timber crowns the heights and slopes of this sun washed land, tapering off into pinon and sagebrush at the lower elevations. Off to the west are the Sierra Nacimientos, the rugged range of mountains lying between the valleys of the Jemez River and the Rio Puerco. And still further west is the desert territory of the Navajo, which extends far into Arizona.

This land has been the home of many peoples. The Anasazi lived there in prehistoric times, and more recently the high country has been the home of the Jemez Indians who ranged far and wide to visit their sacred ceremonial sites (Sando 1982).

The coming of the Europeans brought change to the remote mountains. The Spanish were the first to explore the country extensively; and they recorded its resources of grassy valleys, hot springs reeking of sulphur, immeasurable forests of prime timber, and occasional outcroppings of minerals. The land came to be viewed as valuable and, in time, large tracts were granted by the crown to groups and individuals.

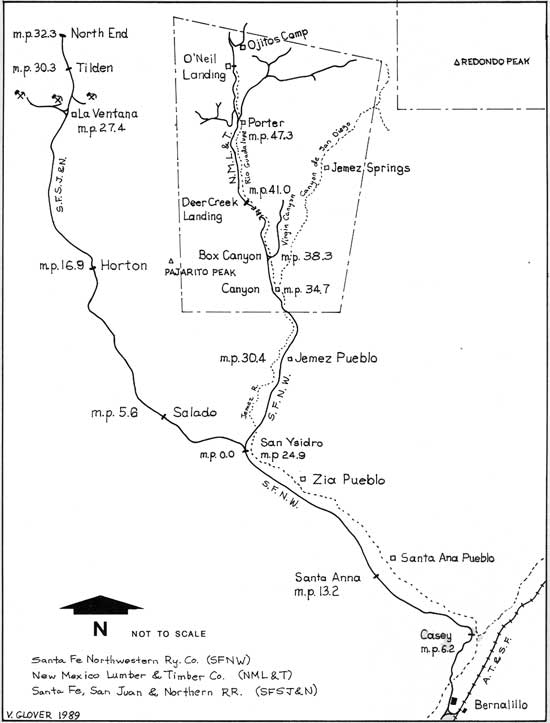

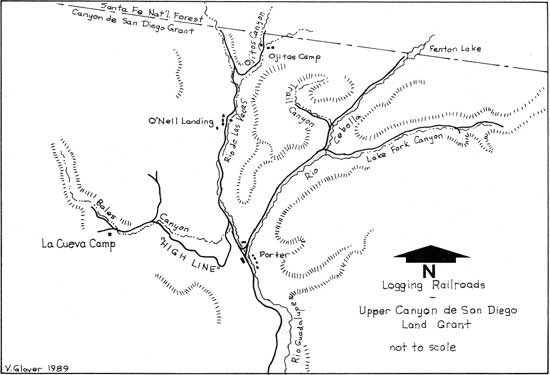

One such tract, the Cañon,de San Diego Land Grant (Figure 2), an area which ultimately measured 116,289.89 acres, was granted on March 6, 1798, to Francisco and Antonio Garcia de Noriega and eighteen others. It was made by Don Antonio de Armenta. Chief Justice of the Pueblo of Jemez, on the authority of Don Fernando Chacon, Governor of the Province of New Mexico (Broudy 1983).

|

| Figure 2. General location map of the Cañon de San Diego Land Grant in northern New Mexico. |

The grant extended about 16 miles from north to south and 12 miles from east to west at its widest point. It was then, as now, characterized by high ponderosa pine-covered hills cut by several very deep canyons which had been formed by the major rivers flowing through the volcanic rock. The canyons generally run from north to south. Through the eastern canyon flows the Rio Jemez, and the Rio Guadalupe runs down the western canyon to join the Rio Jemez near the southern boundary of the grant. Cutting through high hills and mesas, these interconnecting canyons still provide the only practical access routes to much of the grant by either road or trail (USGS Quadrangle Maps: Jemez and Jemez Springs).

The holders of the grant, heirs of the original grantees, were confirmed in their ownership by the United States Congress on June 21, 1861. Shortly afterward the grant directors made allotments of the best arable land to various families among the heirs, amounting to about 6,000 acres. The remainder of the grant was retained as common property (Broudy 1983; Calkins 1937).

One of the main lines of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) system was projected to run up the Jemez River valley on its way west from the Rio Grande valley toward California. The early surveys routed to proposed Atlantic & Pacific (A&P) track northwest from Bernalillo up the Jemez River, then west around the north side of the San Mateo mountains. When the AT&SF attempted to purchase the necessary acreage in Bernalillo for yards and facilities, they met with staunch opposition from Don Jose Leandro Perea. Even after a visit by Lewis Kingman and A. A. Robinson of the AT&SF during February, 1878, the old gentleman placed such a high price on his lands that the railroad moved its planned terminal to Albuquerque (Fierman 1961).

A few years later the AT&SF brought further recognition to the Cañon de San Diego Land Grant when the New Mexican Railroad, a subsidiary of the AT&SF, defined its Route Number 16 as follows in 1882:

Beginning at the best point on the constructed line of the New Mexico & Southern Pacific Railroad [the construction subsidiary of the AT&SF] in the vicinity of Bernalillo, thence in a westerly direction along the valley of the Rio Jemez and the slopes and tributaries thereof to the vicinity of the Jemez hot springs; and a distance of Forty (40) miles in Bernalillo County...." (n, d., AT&SF RR. Engr. Dept. Letter Book).

The New Mexican Railway never built its projected line but interest in the grant continued. During the next few years the area around Jemez Springs became known as something of a health and summer resort.

Mariano Otero had been grazing sheep on the Grant since about 1870. From time to time he purchased tracts of the privately-owned land within the grant, always specifying that with the purchase he also obtained the seller's share in the common lands of the grant. Upon Otero's death in 1904 his heirs claimed ownership of the entire grant. Naturally, the other owners of the grant took exception to these claims, and took the matter to court. Unable to pay their attorney, A. B. McMillan, these land owners offered him half of their interest in the grant. Within a short time, the court ruled in favor of McMillan's clients, recognizing their ownership as well as Otero's. To equitably divide the grant among the many claimants, the court on July 22, 1904, ordered the grant sold (Broudy 1983; Calkins 1937).

On August 22, 1904, the Cañon de San Diego Land Grant was sold by court order to Joshua S. Reynolds, who immediately turned over the title to the Jemez Land Company. The officials of the latter company were Alonzo B. McMillen and Herbert F. Reynolds. Thirteen years later, on October 29, 1917, the Jemez Land Company sold rights to mine the sulphur deposits on the grant to John J. De Praslin who announced plans to build a railroad northwest from Bernalillo into the grant area. Within a few years De Praslin became deeply involved with the coal mines at Hagan, over to the east beyond the Rio Grande; and his sulphur mining venture withered on the vine. Several more years were to pass before another railroad into the Jemez Mountains was announced (Broudy 1983; Calkins 1937).

Building the Santa Fe Northwestern Railway

The next railroad project into the Cañon de San Diego Grant was announced during the summer of 1920. This venture was to be called the Santa Fe Northwestern Railway (SFNW); and it was incorporated in New Mexico on August 20, 1920. Its stated purpose was the development of the coal, copper, timber and sulphur resources of the Jemez Mountains. The proposed route, however, skirted the west side of the mountains instead of heading up the canyons into the center of the grant (Price, Waterhouse & Company 1926).

As initially envisioned the line was to have been a 55 mile long standard gauge railroad extending from Bernalillo, New Mexico, to the tiny village of La Ventana in northern Sandoval County. The route would have taken it through the pueblos of Santa Ana and Zia, past the village of San Ysidro, and across a long stretch of arid land suitable only for grazing. Its projected terminal at La Ventana was close to some promising but undeveloped coal deposits. A few miles to the north lay the copper mines at Senorita, while the timbered Nacimiento Mountains lay to the east. Undeveloped gypsum deposits were known to exist near San Ysidro as well (Albuquerque Morning Journal, August 12, 1920; New Mexico Railroader, May 1961).

The promoter of the SFNW was Sidney Weil, an Albuquerque promoter who was also interested in many other development schemes at the time. Weil was one of the directors of the new railroad company, and the others were also Albuquerque businessmen: Ivan Grunsfield, J. E. Cox, and Lloyd Sturges. The authorized capitalization of the SFNW was listed at $1,000,000, a sum well beyond the resources of the incorporators.

Weil was an energetic character, seemingly involved in almost everything going on in Albuquerque at the time. His record confirms that he was a visionary and a grand persuader, although he was constantly in financial difficulty. At one time or another, he was concerned with raising money to build the Franciscan Hotel, promoting the Miss Albuquerque Pageant, and developing the early beginnings near the town of the Army Air Corps base, which was later to become Kirtland Air Force Base. But many of his other interests were of such a sleazy nature that they must charitably be called promotions or scams.

"Sidney Weil was a little guy, about yay high." said his barber, Steve Gonzales. "He was a good promoter, but he was always owing people money. He was a good ducker. When he'd see somebody he owed coming down the street, he'd duck into a bar or store and buy himself a little something. He always came into the shop for a shave five minutes before closing." (Albuquerque Tribune 1985 [September 14]; 1985 [November 25]).

Weil was not promoting his railroad without a good understanding of its potential. At the time SFNW was incorporated, it was estimated that there were 425 million board feet of ponderosa pine timber standing on the grant with an additional 2 billion board feet available in the adjacent Santa Fe National Forest. A little further away was the Baca Location or Valle Grande on which stood an estimated 500 million board feet of timber. About this time, Weil evidently obtained some sort of option on the Cañon de San Diego Grant timber.

Weil was acquainted with Paul Reddington, who held a high position with the Forest Service in Washington, D. C., at the time, so he was able to request a timber cruise or survey of the government lands near the grant. The cruise was made, and the report came back concluding that the logging in the Santa Fe National Forest was not a promising commercial venture. The reason given was that the cost of building a railroad into the timber area would be prohibitive

Weil's response to the negative report was to challenge some of the current government practices regarding timber. First, he asked Reddington to allocate all of the Santa Fe National Forest timber to a single mill, something that had not been done prior to that time. Next, he requested that they reduce the minimum charge for timber from $3.50 to $2.50 per thousand board feet. These conditions would make it much more feasible to project and finance a railroad into the mountainous timber district. Reddington and the Forest Service evidently agreed to these proposals, although it was to be nearly a decade before such a timber sale actually occurred.

The AT&SF also came under Weil's persuasive powers. He visited Edward R. Chambers, Vice President, Traffic, who sent John R. Hayden out with Weil to look over the La Ventana coal deposits. Hayden was an industrial and traffic development specialist with considerable experience. "Your coal is good, but develop the lumber," was Hayden's advice. With the results of the timber cruise in hand, Weil talked Chambers into setting a special freight rate which provided for a reduction of $5.00 per thousand board feet in the freight rate for all lumber shipped east of Belen, New Mexico. There was also a discussion of the possible development of the silica and gypsum deposits in the vicinity of San Ysidro, but these were discouraged by a letter from Hayden requesting that this not be done. He acted in the interests of the infant silica and gypsum industries in Kansas which were financially backed by the AT&SF (Weil interview).

Little immediate progress was made toward actually building the SFNW, but a search was carried out for investors who could finance one of the industries which the line was intended to serve. Within a year's time, events transpired which led directly to the construction of the railroad. On May 19, 1921, the Jemez Land Company sold the timber on the Cañon de San Diego Grant to Guy A. Porter and his wife, Mary C. Porter, of Charleston, West Virginia, for $1.00 per thousand board feet. The sum of $50,000 was paid by the Porters at the time of the sale. It was announced at the same time that the Porter Lumber Company intended to build a lumber mill at either San Ysidro or Bernalillo. which was to be supplied with logs by a 22 mile railroad running up into the grant. It began to appear as if the SFNW would have at least one shipper in the lumber business (Broudy 1983: Albuquerque Morning Journal 1921 [July 30]).

The relationship between the SFNW and the Porter interests was better defined on September 21, 1921, when the Jemez Land Company assigned the railroad a right-of-way through the land grant. The intention of the SFNW to build the Porter logging branch was confirmed shortly thereafter when civil engineer J. F. Stewart of the AT&SF was loaned to the SFNW for the job of locating the railroad right-of-way from Bernalillo up the Jemez River into the Cañon de San Diego Grant (Broudy 1983; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1921 [December 8]).

A hint of the problems yet to be faced by the SFNW appeared as engineer Stewart returned to the line in December 1921 to survey alternative routes through two places. He relocated the right-of-way through the Jemez Pueblo lands so as not to interfere with the agricultural acreage. The Jemez Indians depended then, as they do now, on farming a narrow strip of irrigated land in their isolated valley. In addition, an alternate route crossing the Rio Grande near the town of Bernalillo was laid out in case there were problems with the alignment of the original route (Sando 1982; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1921 [December 8]).

Planning the new railroad and sawmill occupied the Porter family throughout 1921 and well into 1922. Although Sidney Weil continued to promote the railroad to La Ventana, the lumbermen pushed the construction of a logging line up the Jemez River. As the months passed, it became increasingly apparent that this would be the first route of the SFNW to be constructed. Keeping steadfastly to his La Ventana promotion, Weil during this time obtained from Guy Porter a "perpetual" trackage right over the Porter railroad between San Ysidro and Bernalillo (Weil 1960).

Guy A. Porter was assisted in his New Mexico work by a number of lumbermen from Charleston, West Virginia. During 1922 his two sons, Frank and Lyman, came out to supervise various parts of the work. Lyman Porter headed west to the Zuni Mountains to supervise the cutting of railroad ties and bridge timbers for the SFNW. Later he returned to the Jemez Mountains to work on railroad construction, and to supervise the logging operations. Frank handled the office work at Bernalillo (Curnutte 1987; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1922 [July 2]).

Rails and fastenings (spikes, rail joints, and bolts) were leased from the AT&SF for an indefinite term, the price being set at six percent per year on an asset value set at $35.00 per ton. As will be seen, the role of the AT&SF was to be a significant one in the building and operation of the SFNW. This was to be expected, for the SFNW was a potentially large source of profitable traffic for the AT&SF; and this, indeed, proved to be the case as the lumber business developed (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1922 [October 16]; ICC 43 Val. Rep. 729).

The AT&SF provided a number of services to the SFNW, mostly of a kind in which the technical skill with which they were performed was important: surveying, bridge design and construction, locomotive maintenance and rebuilding work, and the like. In addition to supplying the rail, the AT&SF provided a number of cars and locomotives to the SFNW over the years. And the provision of this hardware, especially the rail and fastenings, gave backing to the lumbermen. To the SFNW it gave a significant subsidy by reducing the amount of capital needed to get the railroad running. In later years, a number of Santa Fe employees found jobs on the SFNW after they had been laid off or dismissed by the bigger road for serious infractions of the rules. Occasionally the AT&SF would re-hire them after a few months, usually as the result of influence of the railroad brotherhoods and their grievance procedures.

It was during 1922 that the name of lumberman George E. Breece appeared in connection with the Cañon de San Diego Grant. With a financial interest in the Porter Lumber Company, as well as interests in the Zuni Mountains of New Mexico, Breece played an important early role in managing and organizing the project. By June, 1922, the town of Bernalillo had purchased 100 acres of land and had presented it to the lumber company for use as a mill site (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1922 [July 2]; Davis 1945:470; Glover 1986).

In the meantime, the lumbering business had been formally organized. The White Pine Lumber Company (WPL) was incorporated in New Mexico on June 26, 1922, with Guy A. Porter as president and George E. Breece as a director. Three men from Charleston, West Virginia, were also directors: Isaac Lowenstein, M. M. Williamson, and Angus McDonald, Frank N. Porter, by then located in Albuquerque, was treasurer and general manager. The $6,000,000 of authorized capital was rather large, and it may be best viewed as a measure of the incorporators' dreams and certainly not as a representation of the funds actually raised at the time (Price, Waterhouse & Company 1926; NMSCC Annual Report 1923; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1922 [July 2 and November 23]).

During the year, WPL began to purchase heavy equipment for logging. One of the first pieces obtained was an American Standard Model No. 1 log loader, built by the American Hoist and Derrick Company. The loader, purchased during July 1922, was equipped with 7 inch by 8 inch cylinders, two hoisting drums, and an eight-wheel extension truck. The latter permitted the loader to run on rails on the log car decks (Figure 3) and to cross the gaps between the cars (WPL Chattel Mortage, 1922).

|

| Figure 3. American Hoist & Derrick Company log loader lifting logs onto railroad cars, circa 1932. The sets of rails on which the loader moved itself from car to car are seen on the left. Following each move the loader picked up the set of rails it had just vacated and swung it into place ahead. (Photo from T. P. Gallagher. Jr., collection) |

By a contract dated September 26, 1922, WPL purchased the timber on the Cañon de San Diego Grant by assuming the debt of Guy A. Porter to the Jemez Land Company. The purchase price was set at $2.00 per thousand board feet, the amount to be determined by a later timber cruise. Later the parties agreed to conclude the transaction on the estimated basis of 400 million board feet (Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1926).

In the early autumn of 1922, bids for the construction of the SFNW were solicited. The bids were scheduled to be opened on October 13, 1922, a date which indicates the time by which sufficient funds were available to start the building of the railroad and sawmill. As the big day approached, the AT&SF installed a siding and connecting switch for the SFNW at the south end of Bernalillo. A storage yard was set up nearby for the rail and supplies leased from the AT&SF and for the new cross ties arriving from the Zuni Mountains (Albuquerque Morning Journal, October 16, 1922).

Bids for the construction of the SFNW were actually opened on October 16, 1922. The contract was quickly awarded to Sharp and Fellows Contracting Company. Work began shortly thereafter on Wednesday, November 8, 1922, when huge plows were used to break ground for the roadbed in Bernalillo. At least one major subcontract was let for the SFNW work, for Ralph Eggleston and John D. Matthews, both of Albuquerque, were deeply involved with many portions of the railroad construction (ICC 43 Val. Rep. 729; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1924 [September 1]).

As the grading of the roadbed progressed north and west from the Bernalillo mill site, the route of the SFNW became clear. The main line ran north from the mill to the Rio Grande bridge. The river was not controlled by northern dams in those days, and high water was common. Nevertheless, an ordinary pile trestle with its multitude of pile bents was built (Figure 4). This decision resulted in troubles in later years. The low SFNW bridge tended to catch a lot of debris in the periods of high water, and it was frequently in danger of being washed out. During these times, a locomotive and work crew had to be dispatched to clear the trestle of debris and trash (Pratt 1960).

|

| Figure 4. Rio Grande trestle soon after its construction in early 1923. Of standard AT&SF design, this structure was built of piles driven into the bed of the river. The embankment on the far side of the river shows the grade as the track begins its climb into the hills on the west side of the Rio Grande behind the camera. (Photo By M. E. Hanna. Albuquerque Public Library collection) |

The AT&SF used its own construction crews and a pile driver to build the first three bridges on the SFNW. The first was only a short span over a ditch, and the second was a trestle over the conservancy district irrigation channel. The third bridge was over the Rio Grande. This was a standard pile trestle with 56 bents set 14 feet apart. The pile driver and its crew worked all winter on the Rio Grande trestle, it being a time of low water and sunny if chilly weather. Work was delayed for nearly two weeks at one point when the hammer and leads of the pile driver broke loose and fell into the river. All of the trestles built by the SFNW thereafter were erected with a ground crane, a stationary boom which lifted each bent into place as it was assembled (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1923 [February 6]; 1924 [September 1]).

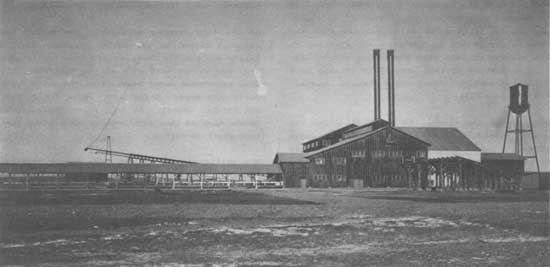

The new sawmill (Figure 5) was to be a large one with the capacity to cut 120,000 board feet of lumber per day using a double band saw. The mill complex was powered by a steam plant with four boilers and two dynamos. A tall water tank of 110,000 gallons capacity towered over the mill and the 12 acre log pond. It soon became the most prominent landmark in Bernalillo, signifying a new industrial prosperity in the old town. Many of the men in town found regular work in the mill, or el molino as it was called. The regular pay was very welcome in the otherwise poor farming community (The Timberman 1924 [April]; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1924 [September 1]).

|

| Figure 5. The sawmill at Bernalillo soon after its completion in 1924. Milling had not started as evidenced by the absence of smoke from the boilers and the lack of activity in the scene. (Photo by M. E. Hanna. Albuquerque Public Library collection) |

Sidney Weil, the early promoter of the SFNW became less and less involved with the railroad as the lumber interests directed its construction up the Rio Jemez and into the Cañon de San Diego Grant, instead of to La Ventana as Weil had envisioned. In order to pursue his own developments at La Ventana, Weil incorporated the Cuba Extension Railway Company on August 11, 1923, with the same Albuquerque men as backers who had earlier incorporated the SFNW. The Cuba Extension, with authorized capital of $650,000, planned to build a 44 mile railroad from San Ysidro through the La Ventana coal district to the village of Cuba near the copper mines. The further history of this company is related in a following section (Albuquerque Morning Journal, 1923 [August 12]).

Once across the river, the track traversed the rugged slopes of the valley of the Rio Jemez through a long series of cuts and fills in rocky ground. Beyond the cliffs the line dropped down a bit and followed the Rio Jemez to the northwest. The roadbed was simply a mound of loose sandy soil with an occasional short trestle or box culvert. The railroad crossed the Santa Ana Pueblo and Zia Pueblo lands, having obtained right-of-way easements in return for employing Indians from the pueblos to work on the grading and fencing of the line (Weil 1960).

Crossing the lands of three Indian pueblos along the railroad route presented a peculiar problem to the SFNW. A pueblo was not simply a remote village in the emptiness of New Mexico. The pueblos of Santa Ana, Zia, and Jemez were independent, sovereign states created by treaty and the law of the United States with considerable powers of self regulation. It was no small thing to obtain a right-of-way easement across lands that had been occupied and used for centuries, but that was exactly what Weil did. As will be seen in the case of the Jemez Pueblo easement, many difficulties were encountered.

At the tiny farming village of San Ysidro the railroad turned to the north, crossing the Rio Salado and the Rio Jemez on low trestles (Figure 6). Now on the east side of the Rio Jemez, the line approached Jemez Pueblo from the south (USGS Quadrangle Maps: Bernalillo, Santa Ana Pueblo, San Ysidro, Jemez). At this point the railroad became engaged in a right-of-way controversy that took years to settle.

|

| Figure 6. Typical low pile trestle crossing an arroyo circa 1923. (Photo by M. E. Hanna. Albuquerque Public Library collection) |

The initial survey of the SFNW simply followed the east side of the Rio Jemez with no concern for the desires of the Jemez people or for their need to use the land for farming. As a result of protests by the Jemez Council, several alternative routes were surveyed during late 1921. During 1922 the right-of-way acquisition process moved through its normal steps, beginning with an appraisal of the property and then, as was hoped, proceeding on to the transfer of title and final payment for the land. Throughout the proceedings, however, the Jemez officials refused to consent to any of the proposed or surveyed rights-of-way, or to accept any payments. Weil's original promise to give a share of the work to the Jemez people was no longer enough to obtain the right-of-way.

Weil resorted to his powers of persuasion and traveled to Washington. D. C., with two representatives of the Pueblo. They reached an agreement to give the railroad a right-of-way easement, subject to the approval of the Department of the Interior. As far as the SFNW was concerned, the matter ended on March 8, 1923, when the Indian Commissioner in Washington granted the railroad permission to proceed with construction across Jemez Pueblo lands. His authority was an Act of Congress dated March 2, 1899, which was presumed to grant authority for such rights-of-way (Weil 1960; Sando 1982).

The building of the railroad across the Jemez Pueblo land was only the beginning of a long series of legal controversies. Railroad construction proceeded during 1923 with only minor problems, while questions about the legality of the right-of-way became a separate issue which did not directly affect the operations of the SFNW. It was not until March, 1924, that the various Jemez landowners accepted their payments for damages caused by the granting of the right-of-way.

A serious question arose later when, on March 1, 1926, the Pueblo Lands Board wrote the Secretary of the Interior stating that the board had found that title to the right-of-way had not been legally granted. Suit was filed in District Court to resolve the matter, and numerous questions were raised during the process concerning the applicability of various laws and statutes (Sando 1982).

During this period, the SFNW began to have difficulty selling their $1.25 million bond issue because of uncertainty over the right-of-way. In response to local pressures, the Attorney General of New Mexico drafted and sent to a United States Senator from New Mexico a bill providing for the condemnation of pueblo lands. The Pueblo Land Condemnation Act, as it became known, was quickly introduced, passed by both houses of Congress, and signed by President Coolidge on May 10, 1926. Significant flaws were soon discovered in this hastily prepared legislation, and another bill was drafted. The revised legislation was signed into law on April 21, 1928. Then the SFNW reapplied to the Department of the Interior, and its right-of-way was reapproved on July 10, 1928. The Pueblo Land Condemnation Act itself caused numerous problems with the pueblos, and it was ultimately repealed on September 17, 1976 (Sando 1982).

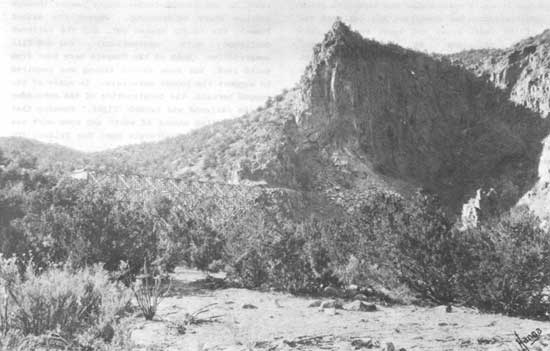

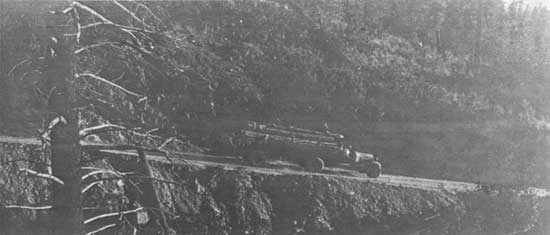

The railroad grade as built followed the east bank of the Jemez River through the pueblo, avoiding the hills and arroyos on the east. Beyond Jemez, the SFNW crossed the Rio Jemez once more at Canyon and proceeded up the west side of the narrowing valley. A few miles further on, the line entered the canyon of the Rio Guadalupe. This point became known as Canyon Landing. The railroad continued up the canyon to the Guadalupe Box or Box Canyon. At this point the open canyon closed in, leaving the railroad facing an abrupt stone cliff. The only opening was a narrow crevasse through which the river flowed in a rushing torrent over rocks and falls (Figure 7). The easy, loose ground construction of the roadbed came to an end, and the much more expensive hard rock work began (USGS Quadrangle Maps: San Ysidro, Jemez).

|

| Figure 7. Guadalupe Box during the railroad era clearly showing the narrow hard-rock canyon. The railroad line can be seen on the left. (Photo made by J. D. Jones on September 3, 1930. USDA Forest Service photo 249032. Copied from the collection of Joseph P. Hereford. Jr.) |

The grading crews reached the Box during October, 1923, and they stopped working until a pathway through the cliffs could be found. Meanwhile the track gangs continued to work. Only twelve miles of track had been laid out of Bernalillo since February, but the pace was increased to 4,000 feet per day in the autumn months. A second steel gang started work at Mile 32 above Jemez Pueblo. With the two gangs working, rail was laid up to the Box by the end of January, 1924 (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1923 [October 11 and December 9]; and 1924 [January 6]).

The track crews used a small locomotive called "the Dooley." It was said to have been a 2-4-2T Baldwin weighing about twelve tons, and its name may have originated with J. R. Dooley, one of the contractors on the railroad work. The locomotive was in actuality owned by George E. Breece, and it had come with him from West Virginia about 1919. For a time it worked in the Zuni Mountains on the logging railroad between Thoreau and Sawyer. Then, about 1923, it was shipped over to Bernalillo to help build the SFNW. The little engine remained for some time on the SFNW and it was used as a switcher at the Bernalillo mill. It was not long, however, until the small size of the locomotive rendered it more useful as a source of steam than as a locomotive. Its boiler ended its days as a stationary steam supply for the machine shop at Porter (Bruce Crow 1960; Curnutte 1987; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1924 [January 6]).

The SFNW track was standard gauge, laid on untreated pine crossties with old 56 and 66 pound-per-yard rail leased from the AT&SF. Much of the rail was of the 56 pound-per-yard weight rolled in 1894, and it had seen heavy use on the main line. Earth was used for ballasting and surfacing the track, especially below the Box (ICC 43 Val. Rep. 729; 249 ICC 342).

The terms of the lease of rail by the AT&SF to the SFNW provided some insights into one of the ways the main line carrier aided the feeder and industrial railroads. The initial lease of December 1922 covered some 16 track miles of light 56 and 66 pound-per-yard rail and fastenings for which the AT&SF no longer had any use. This contract was revised during 1923 to include an additional 45 track miles of similar rail needed to complete the SFNW into the mountains. The new contract, for a term of five years, was approved by the AT&SF during December 1923.

Far too light for even yard or branch line service, the rail was made available to the SFNW for the rental equivalent of six percent interest on a value of $35 per ton. Essentially, this provided rail, joint bars and bolts to the SFNW for a nominal fee of about $14,000 per year, thus relieving the WPL of a capital expenditure of from $150,000 to $200,000 at the open market rates for rail and fastenings. The lease required WPL to furnish a surety bond covering the value of the materials. It also provided that, upon termination, the material be returned to the AT&SF at Bernalillo or purchased from them at the then prevailing market price (W. B. Storey, AT&SF 1927 [September 22]).

Late in 1927 the lease contract was modified to reduce the valuation of the track materials to $30 per ton retroactive to January 1, 1926. It also provided for an additional five track miles which were to be leased to WPL as of March 1, 1927. An additional five track miles of 61 pound-per-yard rail with fastenings was supplied in January 1929. With the added track materials, the SFNW was operating over a total of 71 track miles of leased AT&SF rail, which amounted to approximately 6,753 tons of rail and 488 tons of fastenings (W. B. Storey, AT&SF. September 22, 1927; December 28 and December 29. 1932).

Guadalupe Box

Pushing the railroad through the Guadalupe Box was a job requiring more engineering skill than surveying the entire route from Bernalillo to the Box. Some time earlier, Sidney Weil had hiked into the Box with Robert J. Schmalhousen, the former construction superintendent of the Elephant Butte Dam. Schmalhousen sketched out a route for the SFNW which bypassed the Box on the west by using a series of trestles and tunnels to maintain a steep, but even, gradient. Work on the railroad around the Box apparently began late in 1923, and it took several months to complete (Weil interview; Wickens interview; Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1926).

Although it was a spectacular and expensive piece of construction, the Guadalupe Box railroad was one of the least known and least remarked upon mountain railroads in the southwest. Three-eighths of a mile in length, this segment of the SFNW cost about $500,000 to build, more than half the cost of the entire railroad (Wickens 1960; ICC 43 Val. Rep. 729).

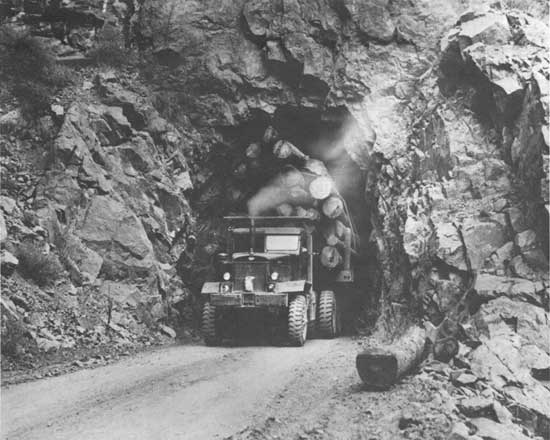

The railroad began its ascent nearly two miles below the Box, climbing steadily higher on the west side of the canyon. Nearing the cliffs, it jumped toward the rocks on a tall timber trestle (Figures 8 & 9) and immediately entered the first tunnel through a spur of rock. A series of fills and trestles clinging to a cliff brought the track to the second tunnel which passed through another rocky outcropping. Beyond the second tunnel, the canyon opened out, and the railroad continued with conventional cut-and-fill construction. Both of the tunnels were hewn from solid rock, but some timber lining was required to support the looser materials. In spite of the rugged terrain, the construction of the remainder of the railroad was termed "light," meaning that only a limited amount of earth and rock work was necessary (USGS Quadrangle Map: San Ysidro; ICC 43 Val. Rep. 729).

|

| Figure 8. The large trestle leading to the Guadalupe Box tunnels during construction, circa 1924. Many features of trestle construction are shown in this view. Note the six piles in each bent, and the numerous horizontal and diagonal braces. The heavy stringers or longitudinal members to support the crossties were being installed at this time. (Photo by M. E. Hanna. Albuquerque Public Library collection) |

|

| Figure 9. The southern approach to the Guadalupe Box, showing the fills and the high trestle required to reach the tunnels. The roadbed was climbing steadily throughout this section. (Photo by M. E. Hanna. Albuquerque Public Library collection) |

An interesting episode occurred in March, 1924, when the Porters announced that an excursion train would be run from Albuquerque up to the Box on March 9th. Special coaches were to be added to AT&SF train number 10 for the journey from Albuquerque to Bernalillo. From that point, a SFNW locomotive would take the cars up to Mile 37, a mile or so below the Box. [See Figure 10 for mileposts and general map of the line.] On March 6 it was suddenly announced that the excursion had been cancelled on the advice of the SFNW attorneys, because, so it was stated, such a train might be construed as an official opening under the rules of the Interstate Commerce Commission. These rules required that regular service be offered to the public thereafter, something the SFNW was not prepared to do. This argument, plausible at the time, takes on the flavor of an excuse for other problems since the SFNW did not even apply for public carrier status until August 12, 1925. This was about a year after it began to operate as a private logging railroad (99 ICC 597; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1924 [March 6]; Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1926).

It was not until August 12, 1924, that the tracks were laid through the tunnels to Mile 42.2, a point just above Deer Creek. The opening of the line to log trains had been routinely predicted in the Albuquerque newspapers throughout 1924, and the sawmill had been finished since January or February of that year. Completion of the railroad was delayed by washouts resulting from cloudbursts during the first week in July; the construction camp at Canyon was heavily damaged by floods which washed out several lengths of roadbed (ICC 43 Val. Rep. 729; The Timberman 1924 [January and April]; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1923 [December 9]; and 1924 [March 4 and July 6]).

Logging operations commenced during 1924. Some logging took place below the Guadalupe Box, but most of the trees were cut along Deer Creek beyond the tunnels (Gallagher 1988: Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1926).

Operating a Lumber Industry

It was not until September 2, 1924, that the White Pine Lumber Company sawmill began cutting.

At this time the two companies employed 200 men in the woods and 100 men at the mill, the SFNW owned about 50 miles of track, 42.2 miles of which were the main line; the railroad cost $971,336.08 to build and equip (99 ICC 597; Albuquerque Morning Journal 1924 [September 1]).

All the required machinery had not been installed as yet in the sawmill, and it was producing only at 52 percent of its rated capacity of 120,000 board feet per day. The planing mill was in operation by March 1925, but the second band saw and other machinery was not installed in the sawmill until September 1925 (Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1926).

At this time, the officers of the two companies were listed as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Officers of Companies Connected With the Timber Operation

| Officer | Title | Origin |

| White Pine Lumber Company | ||

|---|---|---|

| Guy Porter | President | Charleston, West Virginia |

| Isaac Lowenstein | Vice-President | Charleston, West Virginia |

| H. M. Williamson | Treasurer | Charleston, West Virginia |

| Frank N. Porter | Treasurer/General Manager | Charleston, West Virginia |

| Angus McDonald | Director | Charleston, West Virginia |

| George E. Breece | Director | Albuquerque, New Mexico |

| Santa Fe Northwestern Railway | ||

| Guy Porter | President | Charleston, West Virginia |

| George E. Breece | Vice-President | Albuquerque, New Mexico |

| H. M. Williamson | Secretary | Charleston, West Virginia |

| Frank N. Porter | Treasurer | Albuquerque, New Mexico |

| Lyman Porter | Director | Albuquerque, New Mexico |

At this point it is appropriate to say a few words about George E. Breece. He was to play a continuing role in WPL and its successor, the New Mexico Lumber & Timber Company. George Elmer Breece was born in Roundhead, Hardin County, Ohio, in December 1864. Working in the lumber industry all his life, he became a successful lumberman in his own right in the area of Charleston, West Virginia. Beginning about 1907, his interest in New Mexico pine lumber grew until he was in control of the McKinley Land & Lumber Company (later the George E. Breece Lumber Company) in the Zuni Mountains of New Mexico (Glover 1986).

The advent of World War I interrupted Breece's activities in New Mexico. Breece himself was called upon by the U. S. Army Signal Corps to aid in the spruce logging effort in the Northwest. High quality spruce timber from the western slopes of the Coast Range was the primary structural material in aircraft, then urgently needed in Europe. Breece rose to the rank of Colonel before returning to New Mexico. At the time of his earliest involvement with WPL, he was also operating a large logging operation in the Zuni Mountains and a big sawmill in Albuquerque (Glover 1986).

The WPL began logging around Box Canyon and along Deer Creek and its tributaries in the southwest portion of the Cañon de San Diego Grant. The elevation of the timber country ranged from 6,375 feet at the railroad to over 8,000 feet on the slopes of Pajarito Peak. Logs were skidded by horses down to Deer Creek Landing at Mile 41.0 on the SFNW. The new WPL American log loader loaded logs on the four-bunk skeleton frame log cars (Figure 11), twenty of which had been built by Pacific Car & Foundry during 1924. These cars were little more than a heavy center-sill topped with four crossways bunks to hold the logs.

|

| Figure 11. A steel log car of the SFNW in the summer of 1939 at O'Neil Landing. The structure of the car and the design of the log bunks and folding stakes are clearly shown. (Photo by Yale Weinstein) |

Chains and folding stakes secured the load during shipment (Weinstein interview; Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1926; White Pine Lumber Co. 1924).

Logging techniques were typical of the period, cutting and skidding being done with a minimum of machinery and only animal power being used for skidding (Figure 12). There are few signs that wheeled devices, such as bummers or big wheels, were used in the Jemez; but their use was common elsewhere in New Mexico. The new American log loader hoisted one log at a time onto the waiting cars.

|

| Figure 12. Although their use was declining, teams of horses were still used to skid logs in the woods in 1932. (Photo from the collection of T. P. Gallagher. Jr.) |

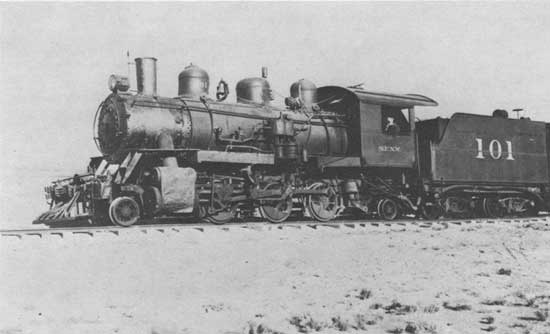

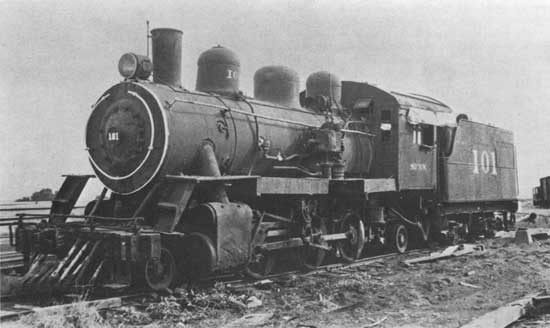

The railroad acquired two locomotives in addition to "the Dooley." Number 101 (Figure 13) was a new low-drivered 2-6-2T rod lokey from the H. K. Porter Company, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This locomotive carried its fuel and water in tanks on the engine frame, and it was a powerful, compact hauler. About 1930 it was converted to a tender type locomotive (Figure 14) and the side tanks were removed. A similar locomotive purchased the year before had been very successful out on the Breece Lumber Company railroad in the Zuni Mountains. The other locomotive, Number 102, was a 72-ton Climax patented gear drive locomotive, said to have been brought from one of the Porter properties in the east (Glover 1967).

|

| Figure 13. M. K. Porter locomotive Number 101 approaching the scene of the derailment of Number 103, circa 1927. (Photo by A. L. "Red" Gleason; from the Gene Harty family collection) |

|

| Figure 14. Santa Fe Northwestern locomotive Number 101 at Bernalillo, New Mexico on July 31, 1939. This view shows the conversion from tank type to tender type. (Photo by Robert M. Hanft) |

The early operating practice was apparently to run trains of empty log cars up from Bernalillo to Deer Creek Landing, stopping at Box Canyon siding to cut off about half the cars before climbing the steep grade ahead. It was at this point that the grade increased to a long steep climb with a ruling grade of four percent in many places.

A second trip was made from Deer Creek Landing down to Box Canyon to pick up the remainder of the train. In railroaders' jargon this was called "doubling the hill", a phrase which simply meant taking a train up a steep portion of the line in two separate sections. The first section was left in a siding at the summit of the grade, while the locomotive returned for the second section of the train. Doubling eliminated the need for a more powerful locomotive or for a second locomotive on the run. Of course, it was a very time-consuming operation, but time meant little on a logging railroad.

North of Jemez Pueblo there was also a "pretty good little hill." in the words of one of the enginemen. It, too, sometimes required trains to double the grade for a short distance.

The powerful locomotives could easily handle full trains of loaded cars all the way to the mill, which was mostly downgrade in favor of the loads except for a short stretch at the mouth of the Jemez River. This was called the "river hill," and trains could generally make a run at it and pull the train up the short grade.

During the early years, any of the SFNW locomotives were used both on the main line and in the woods. Although the Climax would normally be considered a bit slow for the long haul down the Rio Jemez, it was used regularly on the run between Bernalillo and Deer Creek (Bruce Crow 1961).

During the first two years of SFNW operation, a good many changes took place. The railroad was extended much farther into the timber, additional locomotives and cars were purchased, and a new headquarters logging camp was set up.

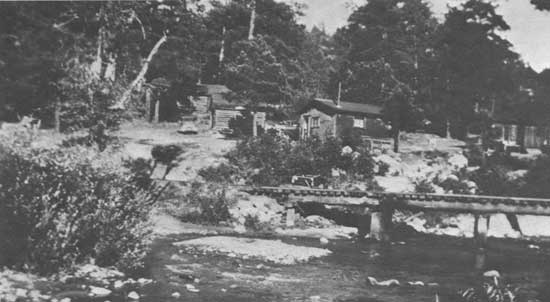

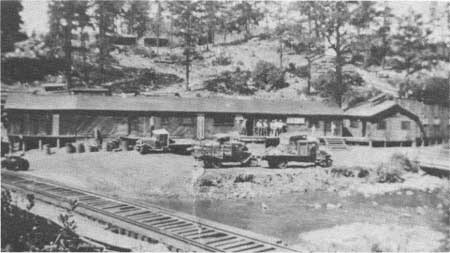

During the warmer months of 1925, after winter had left the high country, the railroad was pushed northward from Deer Creek. This time, however, the builder was the White Pine Lumber Company, not the SFNW. At Mile 47.3 a wider part of the canyon was reached where the Rio Cebolla joined the Rio de las Vacas and became the Rio Guadalupe. There was room here to build the logging camp and the railroad facilities (Figure 15) that were needed for a large logging operation.

|

| Figure 15. Railroad and shop facilities of the White Pine Lumber Company at Porter, New Mexico, during the height of logging activity, September 3, 1930. Box car number 701, a gondola (probably full of coal) and a log loader wait on sidings for the next job. (USDA Forest Service photo number 249031, by J. D. Jones) |

The new camp was called, not surprisingly, Porter; and it became the center of logging activity. It was not long before two or three hundred people lived there, most of them in tiny log cabins scattered through the woods (Figure 16 and 17). There was a rambling company warehouse which included a store (Figure 18) operated by the Porter Mercantile Company. This was a typical "company store" offering the loggers credit and dealing in company tokens as well as in cash. There were no railroad facilities at Porter beyond a wye and several sidings. The legs of the wye crossed the Rio de las Vacas on low timber trestles (Figure 19) (Hammond 1974; Gallagher 1988).

|

| Figure 16. A railroad trestle and dwellings scattered through the woods at Porter, New Mexico, circa 1932. (Photo by Don R. Hammond) |

|

| Figure 17. Don Hammond and his wife lived in this tiny cabin at Porter, New Mexico, circa 1932. It was located just above the company store which he ran. Photo by Don R. Hammond) |

|

| Figure 18. New Mexico Lumber & Timber Company store and warehouse at Porter, New Mexico, circa 1932. Don Hammond was the storekeeper. Motor trucks had become an essential part of the logging activity even this far into the woods. (Photo by Don R. Hammond) |

|

| Figure 19. Railroad trestle and buildings at Porter, New Mexico, circa 1932. (Photo by Don R. Hammond) |

The show place of Porter, however, was the residence of the logging superintendent. Called The Lodge, it was an elaborate seven or eight room house boasting a large stone fireplace and chimney. Years later, the fireplace remained on the hillside as the only tangible sign that Porter ever existed. The ravages of weather, scrap dealers, and road builders had combined to remove or obliterate practically all remains of the once busy camp. Even the railroad bed is now difficult to trace (Hammond 1974; 105 ICC 717; Northnagle 1967).

Although most of its traffic was logs for the WPL mill, the SFNW took it upon itself to apply for common carrier status during 1925. One reason was to encourage traffic along the line, especially coal that might be shipped out by the Cuba Extension Railway connection at San Ysidro. Another reason was to protect its hard won right-of-way across the Jemez Pueblo lands. The first application. approved by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) on August 25, 1925, resulted in public carrier status being granted for the line owned by the SFNW extending from Bernalillo to Deer Creek. A second application covering the line leased by the SFNW from WPL between Deer Creek and Porter was approved by the ICC on March 22, 1926. And, in the same action, WPL was granted trackage rights over the SFNW track from Deer Creek south to Box Canyon siding. These actions allowed the operation of SFNW trains all the way up to Porter, and they also permitted the running of WPL log trains anywhere between Box Canyon and Porter (99 ICC 597; 105 ICC 717; ICC 43 Val. Rep. 729).

In spite of the formalities of trackage rights, train operations seemed to ignore the distinctions between the SFNW and WPL. The original two locomotives were used whenever and wherever they were needed on the logging spurs as well as the main line. The next locomotive acquired by the SFNW was Number 103 (Figures 20 and 21), a sturdy 2-8-0 road engine purchased in July, 1926. It had been built in 1911 for the Marion & Rye Valley, a Virginia road. It was quickly followed in early 1927 by Number 104 (Glover 1967).

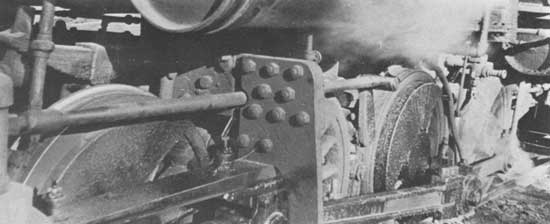

|

| Figure 20. Santa Fe Northwestern Railway locomotive Number 103 is on a log train at O'Neil Landing, circa 1937-1941. This sturdy locomotive served the line throughout its existence. The headlight, pilot, and tender seen in this view are AT&SF standard designs. It is an indication that they had been replaced while the locomotive was on the SFNW. (Photo by Yale Weinstein) |

|

| Figure 21. Details of SPNW locomotive No. 103, circa 1937-1941. Below the cylindrical air brake reservoir can be seen the drive wheels and main rod which actually drove the locomotive. The long rod on the left is the valve actuating rod, controlling steam admission to the cylinders. (Photo by Yale Weinstein) |

During 1926 the 104 had been ordered from the Heisler Locomotive Works in Erie, Pennsylvania. Delivered in January 1927, it was a Heisler gear-drive type of modern design and weighing 70 tons. The Heislers were popular at the time with loggers all over the west, and they were powerful and efficient locomotives (Glover 1967).

The first logging spur built by WPL was the Bales Canyon "high line" (Figure 22) which ran generally westward from Porter. It started up the Rio de las Vacas. A little over a half mile north of Porter, it switched back to the west with big looping curves to gain elevation. A woods camp called La Cueva was reached in about three and a half miles, and short spurs ran up canyons to the north and northwest. The Bales Canyon line was built during 1926 and was used until 1928. After that year it was little used, although the tracks remained in place until about 1933 (Hammond 1974; Curnutte 1987).

The expanded railroad required more rolling stock as well as the additional locomotives. Ten more log cars were purchased to supplement the initial 20. At least some of these cars appear to have been steel cars from the Sierra Madre Land & Lumber Company located in old Mexico. A collection of ordinary freight cars was acquired to carry supplies for the loggers and for use in the maintenance of the railroad. There was a single water tank car, five flat cars, two gondolas, one box car, and two dump cars. Two cabooses provided shelter for the train crews and passengers on the long journey to Bernalillo. Although the railroad's cars were nominally available for use by the public, there is only scant evidence that a very few ever took advantage of those cars. Most of the SFNW cars were used for company business, such as bringing supplies up to Porter and for maintenance work along the line. The upkeep of the roadbed, for example, required the constant renewal of embankments and ballast, as well as the ditching out of cuts and side hills (Official Railway Equipment Register [January] 1926; July 1930).

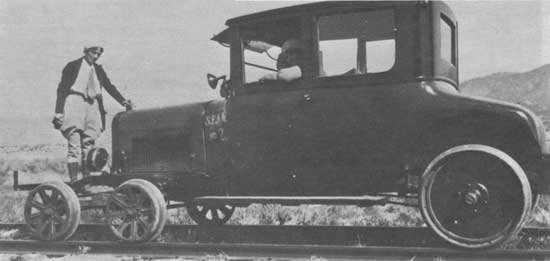

The SFNW built and used what it called rail-autos (Figures 23 and 24). There were a number of these vehicles in use on the tracks throughout the railroad's lifetime. The earliest versions were Ford Model T conversions. The front wheels and axles were replaced with a light four-wheel truck on a pivot, and the rear wheels were simply replaced with flanged wheels gauged for the railroad. With a top speed of about 20 miles per hour and no steering mechanism, the autos tended to last a long time (Gallagher 1988).

|

| Figure 23. Santa Fe Northwestern Railway Number, a simple rail-auto conversion of a Buick coupe. Note the light sheet steel fabrication of the rear wheels. This particular vehicle was called the "Doctor's coupe, for its primary function was to provide transportation to the logging camps for the company doctor. The rail-auto is seen here during October, 1930, on its way to La Ventana over the Santa Fe, San Juan & Northern Railroad. (T. P. Gallagher. Jr, collection) |

|

| Figure 24. One of the more elaborate rail-autos, probably at Porter circa 1932. This four-door sedan was modified with a light four-wheel truck in place of the front wheels and steering gear, and stamped-steel railroad wheels on the rear axle. The ride was hard, but the convenience of such a vehicle was a necessity during the winter months when snow and mud blocked what few roads there were. (T. P. Gallagher, Jr., collection) |

In order to solidify its financing, WPL hired Thomas and Meservey of Portland, Oregon, to make a timber cruise or survey of the timber on the grant. The cruise recorded 527,830,000 board feet of merchantable timber, practically all "California white pine" as Ponderosa pine was termed in those days. The timber was valued on the company's books at $1,847,405.00, which reflected a valuation of $3.50 per thousand board feet (Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1926).

The WPL was able to sell its bonds during the first half of 1926, by which time the company had established its markets and had accumulated some profits. The bonds were 6.5 percent first mortgage gold bonds with a face value of $l,250,000. The underwriter was the Detroit Trust Company, which immediately obtained a mortgage on the entire property (American Lumberman 1926 [June 12]).

By the time of the bond sale, the sawmill at Bernalillo had been expanded into a two-band and resaw mill with additional processing facilities in the form of a lath mill, planning mill, and box factory. An interesting feature of the plant was its contract to sell mill refuse -- sawdust, chips, and slabs -- to the Albuquerque Gas & Electric Company for use as fuel in their power plant. Reported at the time as a "unique situation," the arrangement relieved WPL from bearing the expense of operating a waste burner while at the same time providing a significant source of revenue. Prominent features of the plant included a 12-acre mill pond (Figure 25) and a tall spindly water tank which towered over the plant. It is still an outstanding landmark of Bernalillo (American Lumberman 1926 [June 12]).

|

| Figure 25. The log pond and a string of log cars waiting to be unloaded at the Bernalillo sawmill, circa 1927. (Photo by A. L. "Red" Gleason. Gene Harty family collection) |

Employing hundreds of workers in the woods and in the mill, WPL and its railroad had become an integral part of the community. The SFNW became known locally as el Chileline, a title no doubt borrowed from the familiar narrow gauge line of the Denver & Rio Grande Western running north from Santa Fe (Viva al Pasado 1976).

It appears that WPL established its markets primarily in the east -- principally in Kansas and Missouri -- because the mill at Bernalillo was conveniently located on the main line of the AT&SF; and because Sidney Weil had earlier negotiated a $5.00 per thousand board feet reduction in the freight rates over that line for lumber shipped east of Belen, New Mexico. This put WPL into a competitive position relative to lumber from east Texas (Weil 1960; American Lumberman 1926 [June 12]).

It was in July, 1926, that George E. Breece sold his interest in WPL to Guy Porter. Breece was building a new logging railroad in the Zuni Mountains at that time, and he may have needed the money to complete that expansion (Glover 1986; Albuquerque Journal-Evening Edition 1926 [July 9]).

Traffic volume was slow to build up on the SFNW. In 1926, the first year for which information is available, originating traffic amounted to only 46,218 tons. In terms of carloads of thirty tons, this was equal to 1,541 cars or roughly thirty cars per week. That was the equivalent of two log trains a week throughout the year. Traffic originated during 1927 more than tripled, reaching to 143,540 tons or the equivalent of five or six trainloads per week. Certainly, the additional locomotives purchases during 1926 helped to handle the increase (ICC Statistics 1926, 1927).

Hard Times

The busy times of 1927 were soon destined to end. On December 31, 1927, the Climax locomotive Number 102 blew up on the High Line not far above Porter. Engineer Lewis Crow received a broken leg, broken arm, several broken ribs and other injuries. Lorenzo Deering, the fireman, was scalded severely enough to require hospitalization.

A few days later Lyman Porter and Red Gleason, the Master Mechanic of the SFNW, escorted an insurance inspector to the site of the explosion to determine the cause. The party rode the rails on a Fairmont motor car driven by young Boyd Curnutte. Curnutte (Figure 26) was told to stand away from the wrecked locomotive so he wouldn't hear anything of the discussion concerning the explosion.

|

| Figure 26. Boyd Curnutte, mechanic (left) and Don Curnutte, logging superintendent at the truck repair shop. They were photographed at O'Neil Landing, circa 1939. The Curnuttes worked many different jobs in the woods. Occasionally, when a train crew was not available. Don would go down to Porter, fire up the locomotive, and bring the log train up to O'Neil Landing. (Photo by Yale Weinstein) |

The Climax locomotive had come from West Virginia and was said to be in poor repair when it arrived. The crew of Number 102 had generally taken water from line-side streams, which had been muddy during the previous month. During the Christmas shutdown, the boiler had been drained but not washed out, leaving any mud and sludge in it. When the engine was fired up again after Christmas, the boiler was filled once more with muddy water, and the engine went back to work. The cause of the explosion was said to have been a hot spot on a firebox wall caused by the sludge (Lewis Crow 1960; Curnutte 1987; Albuquerque Journal 1928 [January 2]).

The loss of the locomotive was to be of less importance than might have been expected. By September 1928 the lumber market had deteriorated to the point where logging and milling operations were shut down completely. For a variety of reasons -- declining revenues, lack of operating capital, and a physical plant deteriorating from lack of upkeep -- the company remained shut down until new financing could be found. (Albuquerque Journal 1928 [January 2]; Albuquerque Tribune 1930 [February 11]).

Reorganization

It was not until 1930, following fifteen months of idleness, that the logging operation was revived. In the meantime, the SFNW reported little or no originated tonnage, although several hundred cars of coal originating at La Ventana were handled from San Ysidro to Bernalillo (193 ICC 545).

The WPL was in serious financial trouble by this time, having little revenue out of which to pay the interest due on the first mortgage bonds issued back in 1926, as well as a serious shortage of operating capital to see it through periods of little income. Salvation arrived in the form of a new investor who was willing to pay the interest and assume other accumulated debts in return for a substantial interest in the company.

The new investor was Abram Isaac Kaplan, a successful New York businessman who had been involved in hotels, real estate, fleets of ocean-going tankers, and molasses importation and distribution. Sidney Weil had earlier persuaded Kaplan to provide some of the money needed to complete the Cuba Extension Railway (by then called the Santa Fe Northern). Kaplan had come into contact with the WPL owners during earlier negotiations over a trackage right contract. Subsequently, Kaplan invested a large amount in the WPL company (Gallagher interview).

By an agreement, dated September 11, 1929, Kaplan and his associates acquired a controlling interest in the company. Altogether their investment, which was represented by various forms of notes and securities, amounted to $1,173,025.00. Of this sum, $180,521.30 was used to refurbish the SFNW (Gallagher interview; Linder, Burk and Stephenson 1932 [March 19]).

One of Kaplan's associates was Thomas Patrick Gallagher who moved from New York to New Mexico in 1929. He had worked with Kaplan, and held stock in most of his enterprises. Gallagher quickly assumed a prominent role in the day to day operations of the lumber company. It was soon apparent that between them Kaplan and Gallagher had effectively bought out the Porter and McCorkle interests in the WPL. The stock market crash in October 1929 wiped out the eastern holdings of Kaplan and Gallagher, leaving them with the New Mexico properties as their principal remaining asset (Gallagher interview: 193 ICC 545).

A number of steamship captains and engineers from the Kaplan and Gallagher shipping lines followed them to New Mexico. Jesse F. Bird was a ship's captain who invested some money in the WPL company. In 1929 he became woods superintendent for WPL, but he returned to ships and the sea in 1932. William H. Gilman was another steamship employee who traveled west; he became Vice President (Operations) of the SFNW before his death in 1931. Box Canyon station was renamed Gilman at that time. The railroad operating point at the summit of the "river hill" near the Rio Grande was named Casey for Captain Vincent Casey who stayed a few years in New Mexico and then returned to the sea.

In all, five captains or engineers from the shipping lines followed Kaplan to the New Mexico mountains. Most returned to the sea after a time. Authur J. Sine, on the other hand, was invited into the company because of his extensive sales experience (Gallagher interview).

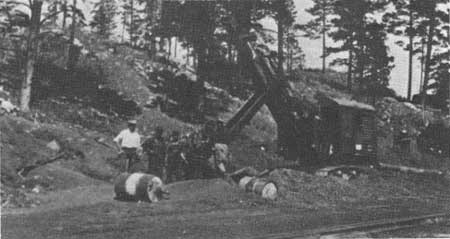

The revitalized WPL started off with considerable vigor. Some 150 men were put to work in the woods cutting timber (Figure 27), while a force of 50 overhauled the sawmill and railroad equipment. New sawmill machinery was installed, and in the woods six Model 60 Caterpillar tractors (Figure 28) replaced many of the horses used to skid logs. A track-mounted steam shovel (Figure 29) was purchased to prepare roadbeds for rail spurs and "Cat" haulage roads (Linder, Burk and Stephenson 1932 [March 19]; Albuquerque Journal 1930 [January 18. January 27 and February 12]).

|

| Figure 27. Bucking a felled tree into logs twenty-feet long for skidding, circa 1932. The chain saw had yet to make its appearance. (From the collection of T. P. Gallagher. Jr.) |

|

| Figure 28. Two caterpillar tractors skidding a log across soft ground circa 1932. The railroad landing can be seen at the edge of the valley in the left background. (From the collection of T. P. Gallagher. Jr.) |

|

| Figure 29. This power shovel on a tracked chassis was used for road building circa 1932. The use of power machinery greatly speeded the work of transporting logs from the woods. (From the collection of T. P. Gallagher, Jr.) |

Lack of repairs during the shutdown had resulted in considerable deterioration of the SFNW track, roadbed and rolling stock. The railroad had to be repaired and its equipment refurbished before log shipments to the mill could be resumed. The roadbed had been damaged by washouts (Figure 30), requiring the reconstruction of 14 bridges along the line. About 110,000 cross ties were replaced to renew the track. Three locomotives were purchased, and the freight car fleet was refurbished and expanded (Linder, Burk and Stephenson 1932).

|

| Figure 30. A large washout of a timber trestle circa 1932. Nearly the entire structure has disappeared, leaving the track swinging across the gully. (From the collection of T. P. Gallagher.) |

During this same period of renewed activity, WPL was the successful bidder on an immense tract of timber offered by the Forest Service for sale north of the Cañon de San Diego Grant. The sale in the Rio de las Vacas watershed involved an estimated 207,900,000 board feet of timber, covering about 40,000 acres of land or more than 60 square miles of forested country. The lumber company's bid was $2.00 per thousand board feet, which was the minimum offer permissible. This figure was well below the $3.50 per thousand board feet to which Sidney Weil had objected years before, and it appears to have been in line with his ideas on the subject. In other words, the Forest Service had followed Weil's desires on a contract negotiated over a decade after he had first expressed them (New Mexican 1930 [September 6]; Albuquerque Journal-Evening Edition 1931 [July 27]; Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1931).

To the lumber company's dismay, the sale was opposed in the press at Santa Fe, the state capital. The "New Mexican" embarked on an extended editorial campaign against the sale, contending in several articles and editorials that long term logging operations would damage the scenic beauty of the mountains and destroy the hunting, fishing, and tourist trade of the district. The Forest Service itself came to the rescue, when Forest Supervisor Frank Andrews noted that the timber sale was being made pursuant to the old agreements upon which the construction of the sawmill and railroad had been originally based. The Forest Service went ahead with the sale, which was completed on September 3, 1930. It was, however, to be some time before logging began in the area (Alamogordo News 1930 [September 11]; New Mexican 1930 [July 22, September 6, and September 11]; Price, Waterhouse & Co. 1931 [April 2]).

In the meantime, the first log train came down from the mountains on January 12, 1930; it was only the first of many needed to fill the mill pond before sawing could begin once more. When the mill opened on February 12, 1930, over three million board feet of timber were floating on the pond. Five hundred men were employed by WPL at that time, half in the woods and half at the mill. The mill began sawing at the rate of 175,000 board feet per ten hour shift (Albuquerque Journal 1930 [January 18]).

The SFNW was hard pressed to keep up with the demand for timber. More rolling stock was ordered, and it arrived as the demand for timber increased. Late in 1929 orders were placed for thirty additional log cars and a second new Heisler locomotive. In addition, the railroad's old freight cars were rebuilt, and additional cars purchased.

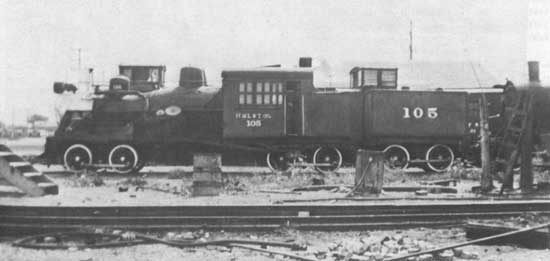

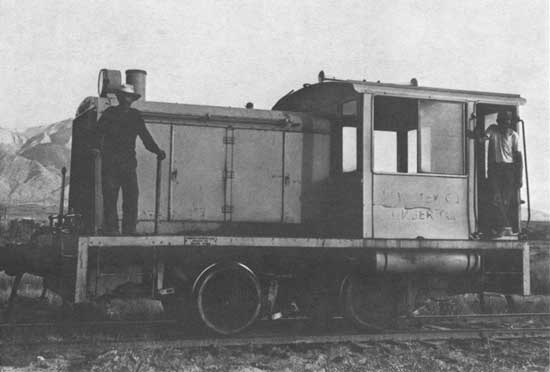

The Heisler, Number 105 (Figure 31), was an 80-ton version of Number 104 with many modern details, such as pressure oil lubrication to all the drive gears. Number 105 arrived during February, 1930, and went right to work. About the same time, the SFNW bought two ancient Pittsburgh ten-wheelers (4-6-0 type) from the AT&SF. Numbered 106 and 107 (Figures 32 and 33), the two old-timers were mostly used for switching at the mill and for handling coal and stock trains between San Ysidro and Bernalillo (Pratt 1960; New Mexico Railroader 1960 [October]).

|

| Figure 31. Santa Fe Northwestern locomotive Number 105 in the sawmill yards at Bernalillo, New Mexico circa 1933. This was the second Heisler geared locomotive on the railroad. It weighed about 60 tons, and all twelve wheels were driven by a line shaft centered under the locomotive. (Photo by Charlie Pratt) |

|

| Figure 32. Locomotive Number 106 of the Santa Fe Northwestern Railway behind the engine house at Bernalillo, New Mexico on May 25, 1933. (Photo by Gerald M. Best) |

|

| Figure 33. Number 107 of the Santa Fe Northwestern Railway at Bernalillo, New Mexico. By this time, the locomotive had been converted to oil fuel and an oil tank was installed in the former coal space of its tender. (Photo by Robert M. Hanft made July 31, 1939) |

As if the three additional locomotives were not enough, the SFNW rebuilt the Porter 2-6-2T Number 101 from a woods engine to a road engine capable of making the run from Bernalillo to Porter. The changes, superintended by Master Mechanic Charles Pratt, involved removing the side water tanks, the cab, and the rear fuel tank. In their places went a "new" steel cab obtained from the AT&SF and the tender from Number 103. This tender was built up to increase both its fuel and water capacity. In turn, Number 103 was converted to oil fuel and received a tender bought from the AT&SF.

Once returned to service, Number 101 proved to be a slippery runner because weight on the drive wheels was sacrificed when the side tanks were removed. The problem was partly solved by the addition of some ballast weight (Figure 34) in the form of old rails and concrete along the running boards (Pratt 1960; New Mexico Railroader 1960 [October]).

|

| Figure 34. Locomotive Number 101 of the Santa Fe Northwestern Railway at Bernalillo, New Mexico, circa 1946 - 1950. Clearly seen are the weights added along the running boards to improve traction and the heavily rebuilt tender with its added water capacity. Photo by Bert H. Ward) |

The old railroad shops had been poorly equipped with machine tools to perform the necessary routine work on the locomotives. Additional equipment and machinery was installed at Bernalillo, and a new locomotive repair shop was built at Porter. There had previously been no railroad facilities whatsoever at Porter. The shop consisted of a cavernous locomotive shed and a number of machine tools. The boiler from the old Dooley locomotive provided power for the machines (Linder, Burke and Stephenson 1932 [March 19]; Curnutte 1987).

During this period, the road locomotives were Number 101 and Number 103. With their larger tenders, these two locomotives could make the round trip from Bernalillo to Porter and back with a minimum number of stops for fuel and water. Each could pull about 30 empty log cars (Figure 35) from Bernalillo to the Box Canyon siding, where about half the train would be left on the siding. For the remainder of the run up to Porter, Number 101 could handle 15 or 16 cars, and Number 103 could pull 12 to 14 cars. Heisler Number 105 could take 22 cars up the line if they were warm from running; otherwise, 18 empties were all it could pull (Pratt 1960).

|

| Figure 35. Train of empty log cars climbing up the grade near Canyon, New Mexico, about 1927. (Photo by A. L. "Red" Gleason; Gene Harty family collection) |

The two Heisler locomotives were the woods lokeys and were normally stationed at Porter. They worked the logging spurs and made trips down the main line to pick up empties at Box Canyon. In addition, they made regular trips down to Bernalillo for maintenance and for the mandatory Interstate Commerce Commission inspections.

All of the SFNW locomotives, even those used almost exclusively in the woods, such as Heisler Number 104, were inspected and certified under the ICC regulations. This permitted them to operate on the upper portions of the SFNW in the vicinity of the tunnels (Pratt 1960).

The SFNW freight car fleet was rebuilt and greatly expanded during the general rehabilitation of the railroad. The company now owned 65 log cars, most of them of steel construction. The other types of cars were rebuilt and renumbered. The freight car roster numbered 86 cars when all the changes were complete (see Table 2).

Table 2. Santa Fe Northwestern Railway Rolling Stock, June 1931

| Car Type | Car Numbers | Quantity |

| Water | 100 | 1 |

| Log, wood frame | 200 - 219 | 20 |

| Log, steel | 220 - 239 | 20 |

| Log, steel | 240 - 265 | 25 |

| Flat | 500 - 506 | 6 |

| Gondola | 600 - 604 | 5 |

| Box | 700 - 704 | 5 |

| Dump | 800 | 1 |

| Caboose | 50, 51, 52 | 3 |

| Total | 86 |

In addition to its own log cars, the SFNW made increasing use of log cars leased from the AF&SF. These were from the group of Class Ft-G steel flat cars built during 1905. The cars were sturdy 40-foot long cars of 40 tons capacity. Many had been equipped from the start with log bunks, and were used initially in log hauling service between Thoreau, New Mexico, and Albuquerque. Over the years these cars found their way into logging service out of Williams, Arizona, and on the SFNW (Pratt 1960; Official Railway Equipment Register 1931 [June]).

Shortly after the mill reopened, an extension to the WPL logging railroad was begun. The track was pushed northeast up the valley of the Rio Cebolla about 7.5 miles to a point beyond Fenton Lake. And, in quick succession, a short spur was laid 7,000 feet up Trail Canyon; and a longer branch was built up the Lake Fork canyon. The Lake Fork branch ended about two miles south of State Highway 126. These lines were very lightly built and ran generally on the floors of open valleys. They served truck and Cat logging in most of the northern half of the Grant (Bruce Crow 1960; Hammond 1974).

On October 12, 1930, the SFNW issued a curious, and, so far as can be determined, unique document in the form of "Employees' Timetable Number 1." It regulated the joint operations of the SFNW and the Santa Fe, San Juan & Northern Railroad, the latter being the Cuba Extension Railway as reorganized and refinanced by Kaplan. The document provided a number of insights into the operations of the SFNW.

Among many other things, this timetable defined normal running times for trains. The running time for the 38.3 miles from Bernalillo to Box Canyon was 3 hours and 16 minutes northbound, and 3 hours and 29 minutes southbound. For the steep nine miles from Box Canyon to Porter, running times were 1 hour and 10 minutes northward, and 1 hour and 29 minutes southward. Locomotive fuel was available at Bernalillo and Porter, while water could be taken on at Bernalillo, San Ysidro, Box Canyon, and Porter. Wye tracks for turning locomotives were located only at Bernalillo, Box Canyon, and Porter. The time table (Table 3) also gave the bell codes for the company telephone system connecting the sawmill offices with San Ysidro and Porter (SFNW/SFSJ&N 1930).

Table 3. Telephone Rings for New Mexico Timber Company

| "OFFICE CALLS" | ||

| Bernalillo | Supt. Office | Three Long Rings |

| Bernalillo | Gate Man | Two Long Rings |

| Bernalillo | Main Office | One Long Ring |

| Bernalillo | Doctor and Time Keeper | Three Short Rings |

| San Ysidro | One Short, One Long, and One Short | |

| Porter | One Short, One Long | |

| Dr. Robert F. Hogsett | Three Short. Co. Phone | |

| Dr. Robert F. Hogsett | 1328-R Albuquerque | |

| W. H. Gilman | 37 Bernalillo | |

| W. E. Rose | 1926-W Albuquerque | |

The SFNW worked harder than ever during 1930. A total of 158,632 tons of freight were originated, almost all of them in the form of saw logs for the mill. This total indicates that the 30 car log trains were run three or four days of the week. This pace held up until the mill was shut down without notice on March 15, 1931, reportedly because of low lumber prices (ICC Statistics 1930, 1931; Albuquerque Journal-Evening Edition 1931 [April 22]).

New Mexico Lumber and Timber Company

It was not long after the mill shut down until the company's largest investor, Abram I. Kaplan, became concerned for the safety of his investment. As a result, he petitioned the District Court to appoint a receiver to oversee the company's operations and finances. His request was quickly granted on April 21, 1931.

The Court's decision to appoint Jethro S. Vaught and E. J. Cox as receivers of WPL also opened the company's debt structure to public view (Albuquerque Journal-Evening Edition 1931 [April 22]; Linder, Burke and Stephenson 1932 [March 19]). The debts included the following:

(1) Kaplan represented to the court that that he was an unsecured creditor for $955,000, of which $755,000 was covered by notes or debentures of the company, and $200,000 was covered by a demand note on WPL. Unpaid interest in the amount of $56,986 was due on the debentures, and $18,500 on the demand note.

(2) The fixed assets of the SFNW, owned by WPL, were under mortgage to secure a bond issue in the face value of $1,200,000, of which $930,000 was outstanding with an $80,000 payment of interest and principal due before June 1, 1931.

(3) Other debts of WPL included unpaid taxes in the amount of $27,599, and accounts payable of $138,819.

Events moved rapidly during 1931. There were apparently a number of lumbermen, including George E. Breece, ready and willing to help pay its accumulated debts in return for an interest in the company. The District Court ordered that WPL be sold at auction on July 27, 1931; and the sale proceeded as scheduled. Only one bid was received in the amount of $1,200,000. This sum was acceptable to the Court; and on August 20, 1931, the assets and obligations of WPL were duly transferred to a new corporation, the New Mexico Lumber and Timber Company (NML&T). The directors of the new company included George E. Breece, T. P. Gallagher. A. J. Sine, and Jesse F. Bird (Albuquerque Journal - Evening Edition 1931 [July 27]; Albuquerque Journal 1931 [September 10]).

Breece and Gallagher were by far the largest investors, and they occupied the chief executive positions. At this point, Kaplan became the silent partner, backing Gallagher. During the next few years, the officers and officials of the company were as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Officers of the New Mexico Lumber and Timber Company

| Officer | Title | Residence |

| George E. Breece | Chairman of the Board | Albuquerque |

| T. P. Gallagher | President | Bernalillo |

| J. F. Bird | Vice-President | Bernalillo |

| A. J. Sine | Secretary and Treasurer | Bernalillo |

| J. S. Hinton | Auditor | Bernalillo |

| W. A. Keleher | General Counsel | Albuquerque |

| A. Larsson | Freight Traffic Manager | San Francisco, Calif. |

| W. E. Rose | Superintendent | Albuquerque |

Breece's involvement was significant because of his expertise in marketing lumber as well as in managing a big logging operation. A. J. Sine was a Chicago lumber wholesaler who invested in the New Mexico company to assure his supply of lumber. By the same token, his investment also assured NML&T of a customer in the mid-West. It was a good deal all around (Gallagher interview).