|

Jemez Mountains Railroads, Santa Fe National Forest, New Mexico

|

|

CUBA EXTENSION RAILWAY

Today La Ventana is little more than a rest stop on New Mexico Highway 44 between San Ysidro and Cuba. Ventana is Spanish for window; and just to the east of the highway are high red rock cliffs, one of which contained the window that gave the area its name. Further east are the timbered Sierra Nacimientos which form the horizon, while to the west is a country of open mesas and broad, deeply eroded valleys. Just off the highway is a cluster of low stone buildings, only one or two of them still habitable. They were once the center of the lively coal camp of La Ventana, a would-be village with a remarkably short life as an industrial center.

Careful observers of La Ventana will see many signs of its earlier life: veins of coal in the nearby sandstone cliffs, lengths of cinder-strewn railroad beds, and some weed-grown dumps of slack coal (Figure 52). Hidden from the view of travelers on the paved highway lie several coal mines. These are marked by the remains of mine tram cars, tumble-down shanties, and one or two sturdy timber mine tipples. La Ventana was once a place of activity and promise: now only a few can remember its very existence.

|

| Figure 52. Roadbed of Santa Fe, San Juan & Northern Railroad at Mile Post 28.5, near La Ventana, New Mexico, circa 1959. [The SFSJ&N was the Cuba Extension Railway as reorganized by Kaplan.] (Photo by Vernon J. Glover) |

The coal at La Ventana had been used to fire the boilers and the smelting furnaces of the copper mines located a few miles to the northeast in the foothills of the Sierra Nacimiento. Records indicate that most of the copper production there occurred between 1880 and 1900, though there was a brief revival in 1919 and 1920. The chief producing copper mines in the district were the San Miguel, the Copper Glance, and the Eureka. For a time in the 1880s, a small smelter of 25 tons-per-day capacity operated at the village of Copper City near Senorita. It appears that in addition to the copper, the ores also contained a substantial amount of silver as well. Unfortunately, the broken and scattered nature of the deposits, as well as the absence of rail transportation, seems to have halted any extensive development of the district (Elston 1967).

Cuba Extension Railway

The coal and copper deposits along the west side of the Sierra Nacimientos were among the destinations listed by Sidney Weil in his prospectus for the Santa Fe Northwestern Railway when he incorporated it in August 1920. As previously recounted, the SFNW never reached the La Ventana district because it became the railroad arm of the White Pine Lumber Company and ran instead into the heart of the mountains. By 1923 Weil was completely out of the affairs of the SFNW; and he then returned to promoting a rail line to La Ventana and beyond to Cuba, an established agricultural village about 12 miles north of La Ventana (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1920 [August 12]).

During July, 1923, Weil announced the incorporation of the Cuba Extension Railway Company, along with his plans to begin construction during the next month. The line was to be 44 miles in length, and its cost was expected to exceed $700,000. The actual incorporation of the Cuba Extension took place on August 11, 1923. The authorized capital stock of the company was $650,000, of which only $4,400 had been paid in. The incorporators were the same Albuquerque businessmen who had incorporated the original SFNW; Sidney Weil, Ivan Grunsfeld, Guy L. Rogers. J. E. Cox, and Lloyd Sturges.

Later announcements concerning the Cuba Extension made frequent references to continuing the railroad beyond La Ventana and Cuba to the town of Farmington. The developing oil and gas fields there would provide very large revenues to any railroad extending into that area (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1923 [July 22 and August 12]).

Several months passed before the Cuba Extension was heard from again. In the meantime. Weil had evidently made a deal with Matthews and Eggleston, the contractors then doing much of the grading work on the SFNW. They put a crew to work on the Cuba Extension in early 1924, and by March 6th had completed 20 miles of light grade north from San Ysidro and 5 miles south from La Ventana. In later years it was learned that Matthews & Eggleston had expended $75,443.89 in doing this work. It was also learned that they had not been paid (Albuquerque Morning Journal, 1924 [March 1 and March 6]; Albuquerque Journal - Evening Edition 1931 [May 26]).

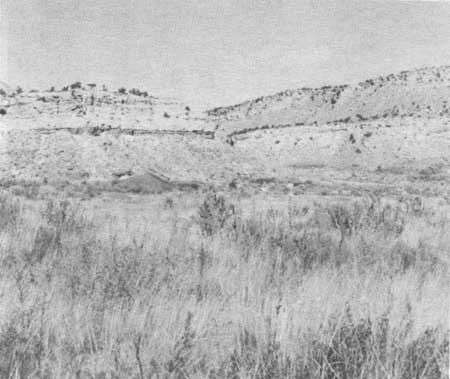

The route followed the Rio Salado for a few miles west and north from San Ysidro, then crossed a low divide into the valley of the Rio Puerco. The railroad grade ran along the east side of the valley, crossing innumerable dry washes which ran with torrents of flood water whenever the snow melted or rain fell in the mountains. The country along the railroad was arid and sandy with a thin growth of grass and mesquite. The ground was easily graded, but it was just as easily washed out after a mountain storm (Figure 53).

|

| Figure 53. Inspecting a washout along the Santa Fe, San Juan & Northern Railroad line to La Ventana in October, 1930. The track has been supported by a cribbing of crossties where the trestle bents have been washed away. (Photo from the collection of T. P. Gallagher. Jr.) |

There was little in the way of settlement or agriculture along the route except near San Ysidro and Cuba. A few cattle grazed on the sparse grass, and that was all. The population along the entire length of the railroad, a distance of over 40 miles. was estimated at 1,970 people. The railroad as surveyed was not a difficult one, involving maximum grades of only 1.50 percent northbound and 1.25 percent southbound. But without the concurrent development of new industries, such as mining or lumbering, there would be practically nothing for the new railroad to carry (154 ICC 473).

At the same time as the railroad was being graded, some efforts were being made to develop the coal deposits near La Ventana. J. P. Hoye of Trinidad. Colorado, began work on several prospects, forming the Sandoval Coal Company to operate them. One of the more promising deposits, located in Section 19 of Township 19 N., Range 1 W., became known as the Hoye Mine. A two-compartment shaft was sunk to a depth of 75 feet. No production was recorded, however, because of the very poor quality of the coal found (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1924 [March 1]; USGS Bulletin 860-C).

Very little more was heard of the Cuba Extension Railway during the next two years. No track was laid, and no coal was shipped out of La Ventana. Exploration work continued on the coal outcroppings, however; and during 1925, the San Juan Coal & Coke Company developed the Cleary Mine (Figure 54) in Section 31, Township 19 N., Range 1 W. The main entry was through an inclined tunnel which followed the six-foot-thick vein of coal. A boiler, a hoist house, and a tipple were built on the surface. Rope haulage was used to pull the loaded coal cars up the incline. Only a few hundred tons of coal were removed during the mine development, and no commercial coal production was recorded during 1925 and 1926. But the San Juan Coal & Coke Company was to play an important role in the future of the railroad (Dane 1936).

|

| Figure 54. Foundations of the tipple at the opening of Cleary Mine at La Ventana, New Mexico; October 27, 1973. (Photo by Vernon J. Glover) |

Sidney Weil and his Albuquerque allies had few resources with which to build the Cuba Extension. In the AT&SF, however, they had an important ally, one easily capable of aiding, or even building, the projected railroad. Weil must have exercised all of his powers of persuasion to draw the AT&SF management into his plans. And he was very successful. During January 1926, locating engineer D. M. Bunker, on leave from the AT&SF, began the final survey of the Cuba Extension Railway from La Ventana to a point near Farmington. This survey work continued for several months using a 14 man crew to run lines and calculate cross sections of the final location of the railroad (New Mexico State Tribune 1926 [January 28]; Albuquerque Herald 1926 [February 15]).

Of greater immediate significance was the aid given to the construction of the Cuba Extension. On March 10, 1926, the AT&SF contracted to provide the Cuba Extension Railway with all the track and bridge materials needed for the entire railroad. The material was to be leased at the going rate until it could be purchased. The transaction was to be completed on or before March 1, 1928 (AT&SF Ry 1926 Contract).

The materials contract prepared by the AT&SF was very detailed; and it provided a thorough description of the railroad as it was planned, and, to all indications, as it was actually built. The AT&SF agreed to deliver to Bernalillo, New Mexico, the following track and bridge materials:

- 4,714 tons of second hand 75-pound per yard rail at $30.40 per ton valuation

- 14,080 second hand Weber rail joints at $30.90 per ton valuation

- 35,000 tie plates

- 14,080 new fillers

- 1,335 kegs of spikes

- 500 kegs of track bolts

- 3,314 bridge ties

- 21 track turnouts

In addition, the AT&SF was to provide local pine ties and bridge timbers purchased from an individual along the line, who was to make delivery directly to the Cuba Extension:

- 34,256 linear feet of trestle piling

- 237,498 board feet of native pine bridge timber

- 81,610 board feet of native pine box culvert timber

- 60,000 each native pine track ties

(AT&SF Ry Contract 1926).

Track laying apparently began late in March 1926. after the rails and other materials started to arrive at Bernalillo, Building even a light-duty railroad such as the Cuba Extension was no small task. Some 146 carloads of material were delivered to the line at San Ysidro during the spring and summer of 1926. In addition, the ties and timbers were sawed locally. To produce them a small sawmill was set up by Lew Caldwell in lower San Juan Canyon of the Nacimientos to cut the special timbers and ties.

The laying of the track proceeded slowly. By June 11, 1926, only two miles of main tracks (as well as the sidings for material storage) had been laid. Nevertheless, Weil announced that seven crews were hard at work on the line. Work under way included finishing of rock cuts between Mile 10 and Mile 17, and completion of the "small amount of earthworks remaining." Bridging materials were on hand, and the first bridge at Mile 7 was being made ready for the track layers. Weil stated that the trains would be running by September.

Reports later in the year indicated that the track reached a point three miles south of La Ventana by September, 1926, but that an additional three miles of grading was needed to complete the railroad (Albuquerque Journal 1926 [April 6]; Albuquerque Herald 1926 [June 11]; Albuquerque Journal Evening Edition 1926 [September 20]; Albuquerque Tribune 1973 [February 24]).

Even with the aid of the AT&SF, completion of the Cuba Extension was not a sure thing. Not withstanding the missing three miles of roadbed, Weil was still able to scrape up some cash. This he used to complete the roadbed and lay the missing three miles of track. But it took several months to do so. On January 31, 1927, it was announced that the First Savings Bank & Trust Company had opened a line of credit for Weil, secured by a first mortgage on the Cuba Extension Railroad. Very little of this was immediately available in cash, for the entire railroad at that point represented at most an expenditure of about $335,000. And almost all of that was still owed to grading contractors and to the AT&SF for the ties, rail and bridge timbers. Some small amount of cash, however, may have been advanced to Weil for use in completing the railroad (154 ICC 741; Cuba Extension Ry. 1927).

San Juan Basin Railroad

As the Cuba Extension Railway tracks neared La Ventana, Weil made another of his surprise moves. Although he had long been stating that the financing of the Cuba Extension had been arranged. Weil found it necessary in mid-August to incorporate the San Juan Basin Railroad. Capitalized at $4 million, the new line planned to build its railroad from Hahn, a point just north of Albuquerque, to Farmington. The projected 166 mile route passed through San Ysidro and planned to utilized the Cuba Extension tracks. The incorporators of the San Juan Basin Railroad included Ernest R. Hunter. Matt Simon, and Sidney N. Weil. Hunter was a New York investor who was also involved with the Cuba Extension. Following a flurry of initial announcements, little more was heard of the San Juan Basin Railroad (Albuquerque Journal 1926 (August 14]; New Mexico State Tribune 1927 [August 30]).

Santa Fe Northern Railroad

Despite his efforts, months passed before Weil was able to push his track all the way to La Ventana. During the spring and early summer of 1927, however, some progress became apparent. Construction was resumed on the frustrating three-mile gap in the grade below La Ventana; and, finally, the track was completed into La Ventana. as preparations began for a grand railway celebration.

In the meantime, something had happened to the railroad's name. With no particular public notice, the Cuba Extension Railway was transformed into the Santa Fe Northern Railroad through the simple expedient of changing the corporate name. For that matter, no specific reason for the name change became evident. One newspaper account, obviously worded by Weil himself, makes an attempt to associate the Santa Fe Northern with the Santa Fe Northwestern, by referring to the SFN as the "second division" of the other railroad (193 ICC 545; Albuquerque Journal 1927 [June 22. July 8 and November 2]).

During May and early June 1927 a number of special events took place that foreshadowed the completion of the rail line to La Ventana. On May 18 Governor R. C. Dillon and Corporation Commissioner Hugh Williams were treated to a ride on the pilot of a SFNW locomotive over the new railroad. Characterized as an official inspection, the trip reportedly ended three miles south of La Ventana. Grading work was still going on between that point and la Ventana itself (Albuquerque Journal-Evening Edition 1927 [May 19]).

A few weeks later, on June 9, the completion of the track to La Ventana was celebrated when the train pulled into town carrying the "first passenger coach ever operated into the frontier of northern New Mexico." The stage was set for the official celebration a few weeks later (New Mexico State Tribune 1927 [June 10]).

The promised grand celebration of the completion of the track to La Ventana took place on Thursday, July 7, 1927. Governor R. C. Dillon and a handful of state officials came down by auto from Santa Fe to Bernalillo for the occasion. An eight car special train, it was reported, took them on the SFNW to San Ysidro, and then over the new track of the Santa Fe Northern to La Ventana. The celebration took place at the end of track. As the small crowd looked on, Governor Dillon drove a gold spike to mark the completion of the track. Dillon and Weil posed for an official photo by photographer L. A. Graham. Also on the scene was one of the eastern investors in the road, Ernest R. Hunter. And, then the occasion was capped with a grand barbecue, enjoyed by everyone after their long journey. Newspaper accounts of the event referred to the ceremony as marking the completion of "the second division of the Santa Fe Northern." which would be interpreted as another attempt by Weil to associate his road with the SFNW (Albuquerque Journal 1927 (July 6 and July 8]).

It must have been about this time that Weil, with a little money in his pocket, built an elaborate "hotel" at remote Marion Butte several miles north of the end of track. The elegant hotel building was used for entertaining guests and potential investors in the railroad and mining enterprises. The remote location of the ranch, however, has resulted in it becoming one of the greater mysteries of the Santa Fe Northern project. Marion may have been the projected division point on the railroad, located about halfway between Bernalillo and Farmington. Or it may have simply been another town site promotion (Gallagher 1988).

In spite of good intentions, laying track and driving a "golden spike" were not enough to create a railroad. In fact, there was little more to the Santa Fe Northern than the track itself and a construction shanty or two. Notwithstanding its new name and Weil's persuasive powers, the Santa Fe Northern failed to begin operations. Once the special train had left the Santa Fe Northern's track at San Ysidro, nothing more happened. Months passed, and the railroad lay idle. No trains ran, and no coal was shipped from the mines.

The next chapter in the tale of the Santa Fe Northern began in early October, 1927, when Ernest R. Hunter, one of the eastern stockholders in the line, brought an action in the Federal Court in Santa Fe requesting the appointment of a receiver to manage the affairs of the railroad.

On October 10, 1927, W. A. Keleher, a prominent Albuquerque attorney, was appointed as receiver of the Santa Fe Northern. Weil stated in the press that the action was a friendly one and that it would not affect his plans for building the railroad (Weil 1960; Albuquerque Journal-Evening Edition 1927 [October 10]).

Keleher quickly worked to preserve the property and rights of the railroad and its investors. In one action he received the permission of Federal Judge Colin Neblett to issue $21,000 worth of receiver's certificates to pay current expenses of the line. In another move, Keleher brought suit in the name of the Santa Fe Northern against the SFNW to test the alleged trackage rights over the SFNW granted back in June 1922. It was claimed that Guy Porter, who had died in Chicago a year earlier, had agreed to give trackage rights between San Ysidro and Bernalillo to the Santa Fe Northern over the SFNW. The trackage right provision was said to be part of the contract of June 22, 1922, by which Weil turned over his rights to the Santa Fe Northwestern Railway to the White Pine Lumber Company. As it turned out, this issue was overtaken by events later in the year, and was never decided in court (New Mexico State Tribune 1927 [November 3]; Albuquerque Journal-Evening Edition 1928 [January 18]); Albuquerque Journal 1927 ]November 2]).

As the circumstances of the receivership became better known, another story began to unfold. It appears that Weil, back during 1926, had obtained the money needed to build the railroad from Abram I. Kaplan, the same New York businessman who would bail out the SFNW in the years to come. It seems that Weil had been introduced to Kaplan during one of his trips to Washington or New York. From that time on, Kaplan appears to have been a willing investor in Weil's projects and related businesses. It was later revealed that Kaplan had loaned $206,000 to the Santa Fe Northern for construction purposes and that he received, as security, bonds of the company with the par value of $146,500 as well as stock having a par value of $1,250,000 (154 ICC 742; Weil 1960).

As the receivership progressed, it was learned that construction costs of the railroad had been advanced by numerous individuals and companies, and that there were several potentially conflicting claims against the property of the railroad. One anecdote tells of Sidney Weil obtaining staple foods for his construction crews on credit at a different Albuquerque grocery store each week. While these claims were being sorted out in court, another of the involved parties began to act.

The San Juan Coal & Coke Company (SJC&C) was ready to ship coal, and they took steps to run the railroad themselves. They had spent more than $50,000 developing their mine and were anxious to begin shipping coal. The coal operators filed a protest with the New Mexico Corporation Commission seeking to compel the Santa Fe Northern to issue rates on coal shipped from La Ventana to points beyond Bernalillo, the terminus of the SFNW. The initial response of the SFN was that the trackage right issue had to be resolved first. Ultimately, the railroad and the SJC&C company began to work together (New Mexico State Tribune 1927 [November 3]).

The first step was to work out an agreement with receiver Keleher, whereby the SJC&C would operate their own trains between La Ventana and San Ysidro. As the Santa Fe Northern had no locomotives or coal cars, this meant that the coal mining firm would have to purchase or lease suitable rolling stock. The AT&SF could be expected to provide suitable coal cars, as it did for all the mines in the area; but SJC&C would have to find its own locomotive.

Next, the SJC&C petitioned the New Mexico State Corporation Commission to determine and publish freight rates for coal shipped from San Ysidro to Bernalillo over the SFNW and to points beyond. A hearing was held, and the Corporation Commission responded on February 9, 1928, with an order providing that existing coal freight rates, which applied equally from Waldo, Hagan, Madrid, or Cerrillos, would also apply from San Ysidro for coal shipped over the SFNW and AT&SF. The order, in effect as of March 9, 1928, placed the La Ventana coal on the same basis, in terms of transportation costs, as other coal mined in that part of central New Mexico (Albuquerque Journal - Evening Edition 1928 [January 28 and February 9]; New Mexico State Tribune 1928 [January 28]).

There was still some work to be done on the railroad before the SJC&C could begin to haul out its coal. A spur to the mine had to be built, crossing the Rio Puerco on a timber trestle. This spur ultimately extended about a mile to the west, reaching the Luciani mine (Figure 55) as well as the Cleary mine.

|

| Figure 55. Site of Luciani Mine near La Ventana, New Mexico, on October 27, 1973. (Photo by Vernon J. Glover) |

The first SJC&C locomotive was one leased and later purchased from the always helpful AT&SF. It was Number 377, a small outdated ten-wheeler (4-6-0 type) built in 1887 by the Pittsburgh Locomotive Works for the Atlantic & Pacific. Like others of its class, it was working out its final years on branch lines and odd jobs around New Mexico for the AT&SF. Weighing less than 60 tons, the locomotive was powerful enough to move a few coal cars on the SFN.

The second SJC&C locomotive was a newer and heavier ten-wheeler purchased from the New Mexico Midland Railway, a moribund coal hauler in Socorro County, New Mexico. This 75 ton locomotive had been built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1901 for the El Paso & Northeastern. Its ownership passed to the El Paso & Southwestern in 1905, and it became New Mexico Midland Number 2 in 1920. Neither of the two SJC&C locomotives was repainted (Figures 56 and 57), and both carried their previous owners names and numbers until they were junked (Glover 1967).

|

| Figure 56. Locomotive Number 377 of the San Juan Coal & Coke Company at La Ventana in the late 1930s. The rails were removed from under the locomotive, and numerous parts had been salvaged. |

|

| Figure 57. Locomotive Number 2 of the San Juan Coal & Coke Company at La Ventana, New Mexico, in the late 1930s. The locomotive stood where it was abandoned for several years until it was cut up for steel scrap during World War II. The locomotive still carried the lettering of its previous owner, the New Mexico Midland. |

The SJC&C began shipping coal to market on March 15, 1928. The locomotive would make two or three trips a week taking between five and ten loaded coal cars to San Ysidro and bringing a string of empties back. Records indicate that the Cleary mine produced 10,500 tons of coal during 1928. Allowing for mine and railroad consumption, this indicates that over 300 carloads were carried over the Santa Fe Northern. And shipments continued on into 1929 at an even greater rate (Hammond 1974: Dane 1936; Albuquerque Journal 1928 [March 16]).

J. G. Cleary, who ran SJC&C, depended on the SFNW for almost everything connected with his railroad in the way of supplies and maintenance. At one point he got into trouble with the ICC by running a locomotive down to Bernalillo for some work. An ICC locomotive inspector caught the locomotive off of its own line and red-tagged it for numerous discrepancies. This meant that the locomotive could not be operated until the defects had been repaired and the repairs were approved by the inspector.

An interesting contemporary document reveals something about the SJC&C operation. The railroad's only source of water was the SFNW water tank at San Ysidro, which drew water from the Jemez River. After the SJC&C had been running trains for some time, the State Engineer's office required that the railroad apply for water rights, which it did. Their application for the use of 0.25 acre feet was duly approved on November 20, 1928. The application incidentally revealed that Sidney Weil was still a director of the Santa Fe Northern and that V. A. Coffey was Chief Engineer (Santa Fe Northern Railroad 1928 [November 20]).

By this time the settlement of La Ventana had grown into an active little town. Max Baca ran a store, which also housed the post office. The El Nido Hotel, a restaurant, a dance hall, and a pool hall catered to the needs of miners, travelers, and railroaders alike. The stores operated by Fred Maboub and Joe Marchetti completed the commercial section of town. It was said that La Ventana was a "wide open" place, featuring all the usual vices. This could well have been true, for it was a long way from there to the Sheriff's office in Bernalillo (Hammond 1974).

In the meantime, the Santa Fe Northern track had been extended a few miles to the north, reaching Mile 30.3 at a spot called Tilden. Here the track stopped at the site of a construction camp made up of hastily framed buildings. There was just an office, a cook shack, and a bunk house. There were no sidings or other railroad facilities. At La Ventana, however, some construction of spurs serving various coal mines (Figure 58) continued; and the railroad had an office there to accommodate Don Hammond, the timekeeper and station agent (Hammond 1974).

|

| Figure 58. Cleary Mine of the San Juan Coal & Coke Company, circa 1930 - 1932. This mine was the largest producer in the district. (Photo by W. G. Pierce; U. S. Department of the Interior, Geological Survey photo) |

In terms of physical plant, the Santa Fe Northern was about as simple as a railroad could be. Mostly, it consisted of 30.3 miles of main track with sidings at Salado, Horton, and La Ventana. There were several mine spurs at La Ventana, and there was a single interchange track at San Ysidro. The only water supply available was, as previously noted, the SFNW water tank at San Ysidro. The railroad owned no locomotives, but it did eventually acquire four gondolas and four flat cars. Other property included two motor track maintenance cars, two section houses, two bunk houses, and three frame dwellings. There was, however, no telegraph or telephone line; and railroad business was evidently conducted over the commercial telephone at the SJC&C office (SFNW/SFSJ&N 1930 [October 12]; Santa Fe Northern RR 1928 [October 11]).

It appears that SJC&C continued to haul its own coal for some time, certainly through October, 1929. The Santa Fe Northern remained in receivership while the court made several attempts to sell the property to satisfy its debts. The first sale took place on June 14, 1928: the only bid received was in the amount of $21,000 from the First Mortgage Company in Albuquerque. This was far too little for the value of the property, and the Federal Court rejected the offer. The court, however, did approve the sale of the ranch house and land at Marion Butte to O. N. Marron of Albuquerque for $250 (Albuquerque Journal 1928 [June 14]).

The next sale of the Santa Fe Northern involved a very complex series of actions, and during this period the railroad acquired yet another name.

Santa Fe, San Juan & Northern Railroad

The final sale of the Santa Fe Northern Railroad occurred on September 5, 1928. The only bidder this time was Sidney Weil, acting not for himself, but as agent for Abram Kaplan. He bid $45,000 for the railroad, a sum which proved to be acceptable to the court. The sale was approved on September 26th. Transfer of the property from receiver Keleher to Weil took place on October 11th; and the final transfer from Weil to Kaplan occurred on November 24, 1928. The deeds carefully included the provision that they were subject to the rights of the AT&SF under the contract of March 10, 1926, with the Cuba Extension Railway. This was the contract by which the AT&SF had provided track and bridge materials to build the railroad (154 ICC 473; Santa Fe, San Juan & Northern RR. 1928 [October 11 and November 24]).

Now Kaplan took charge of the railroad; and he initiated the steps necessary to consolidate its operations with those of the SFNW, of which he was also working to gain control. His first move was to obtain trackage rights for the Santa Fe Northern over the SFNW between San Ysidro and Bernalillo, This was accomplished through a contract dated November 28, 1928 between Kaplan and Frank H. Porter, president of the SFNW. Kaplan agreed to pay the SFNW $200,000 for the rights; ten dollars immediately and the remainder on the basis of tonnage actually transported over the SFNW. This contract made Weil's earlier claim of "perpetual" trackage rights between San Ysidro and Bernalillo a moot point (154 ICC 742; SFSJ&N 1928 [Nov. 28]).

The next steps toward reorganizing the railroad took several months to complete; in the meantime. SJC&C continued to run coal trains on its own over the Santa Fe Northern. Kaplan's next action was to incorporate his newly acquired railroad in New Mexico. This was accomplished on December 9, 1928; and the railroad was thereafter known as the Santa Fe, San Juan & Northern Railroad (SFSJ&N). The authorized capital stock was a nominal $50,000. The incorporators were listed as Abram I. Kaplan. Morris Astor, and H. F. Mela, all of New York; and Sidney M. Weil and Guy Rogers of Albuquerque. Kaplan was recognized as the majority stockholder (Albuquerque Journal 1928 [December 20]).

The application to the ICC to operate the line as a common carrier was approved on July 8, 1929. In its approval, the ICC authorized the SFSJ&N to

(1) operate its own line of railroad.

(2) construct an 11 mile extension from Tilden to the village of Cuba, and

(3) operate under trackage rights over the SFNW between San Ysidro and Bernalillo.

Next, the SFSJ&N was granted authority by the ICC to issue its common stock, which was to be delivered to Abram I. Kaplan in payment for the railroad property, the trackage rights, and the cash advanced for construction. Therefore, it was not until November 1, 1929, that the SFSJ&N actually began operation as a common carrier, ready to serve the general public (154 ICC 473; 154 ICC 741).

In the meantime, Kaplan had also acquired a controlling interest in the Santa Fe Northwestern Railway, the connecting link between the SFSJ&N and its customers. This eased the way by allowing the SFSJ&N to open for business using many of the resources of the SFNW (193 ICC 545).

During the first ten months of 1929, while SJC&C was running its own trains, about 400 carloads of coal were shipped out of La Ventana. The Cleary mine of SJC&C continued to be, by far, the largest producer. As the year progressed, small shipments were made by two additional mines: the Nance mine of the White Ash Coal Company and the Anderson mine (Figures 59 and 60) owned by the Carbon Coal Company (Dane 1936).

|

| Figure 59. Loading chute at Anderson Mine, west of La Ventana; October 27, 1973. (Photo by Vernon J. Glover) |

|

| Figure 60. Site of Anderson Mine, west of La Ventana; October 27, 1973. (Photo by Vernon J. Glover) |

In the meantime, the New Mexico State Corporation Commission (NMSCC) had been watching the SFSJ&N situation closely. As the railroad made its preparations to commence public operation, the NMSCC published new rates for hauling coal within New Mexico. The rates for carrying coal from the Waldo, Raton, Dawson, and Gallup districts were reduced, while the La Ventana rates were increased. The rates for moving coal from La Ventana to Albuquerque, Las Vegas, and Belen were set the same as those for coal shipped from Gallup to the same points. Thus, coal from Waldo was cheaper to move from the mines to Albuquerque. Both Weil and SJC&C complained formally to the commission, and on November 6, 1929, the NMSCC set the La Ventana rates at 20 cents a ton above the Waldo district rates. This reduced some of the competitive advantage of the La Ventana coal (New Mexican 1929 (October 17]).

The railroad to La Ventana was changed very little when the SFSJ&N began its operations. About the only visible change was the use of SFNW locomotives to handle the trains of coal cars. The coal business held up well with 220 cars going out during the last two months of 1929. During 1930 a total of 853 carloads were moved from La Ventana, and 353 carloads were shipped during the first four months of 1931 (Wickens 1960; 193 ICC 545).

Maintenance of the SFSJ&N track and bridges was also taken over by the SFNW. Charlie Pratt, then the Master Mechanic of the SFNW, remembers that it was his regular duty during the summer thunderstorm season to telephone La Ventana every Monday to determine how many bridge timbers and ties had to be cut to repair the latest washouts. Usually, repairs to the soft roadbed could be accomplished before the next coal train ran (Pratt 1960)

Sometimes the washouts caught one of the infrequent trains and dumped a car or two into the sandy streambed. At one time, the railroad had two cars (a box car and a tank car) buried in sand washed downstream from the mountains. For a time, a shoo-fly track and temporary wooden trestle bypassed the wrecked cars (Gallagher 1988).

The joint SFNW/SFSJ&N employees' timetable issued on October 12, 1930, provided further details of SFSJ&N operations. Trains were scheduled to run only on Wednesday, compared to daily except Sunday, on the SFNW. Running times averaged about 15 miles per hour, which was almost too fast for the heavy coal cars on the soft roadbed. The only source of boiler water for the locomotives remained the SFNW tank at San Ysidro, but coal fuel was available at La Ventana (SFNW/SFSJ&N 1930 (October 12]).

During 1929 and 1930, the general economy had been slowing; and the market for coal decreased. Evidently, the money to repair the regular washouts of the SFSJ&N came to an end in 1931. When two trestles were washed out during April of that year, the anticipated repairs were not made and the railroad ceased running. Once more SJC&C had to resort to the courts in order to keep up its coal shipments. This time J. G. Cleary of SJC&C filed a complaint in the District Court, Second Judicial District of New Mexico, requesting the appointment of a receiver to manage the SFSJ&N. The coal company was itself in receivership, with little hope of financial recovery unless coal shipments could be resumed. Months passed; but on October 14, 1931, the court ordered the SFSJ&N into a limited receivership, appointing George C. Taylor as receiver (193 ICC 547; Albuquerque Journal 1931 [October 14]).

Taylor took his appointment seriously, and he went right to work repairing his railroad. By November 12, 1931, service had been restored and the coal trains ran down the line once more. The repairs had been made quickly and cheaply, simply by laying the track on the ground across the shallow watercourses and bypassing the damaged trestles. The catch, of course, was that these usually dry gullies would run with water again after the snow melted in the mountains. This simple approach worked fine through the winter, and a few more carloads of coal managed to get to customers. But the running water washed out the railroad once more on April 15, 1932, just about a year after the earlier washouts (193 ICC 547).

In the meantime, another legal side show opened to affect the railroad. During May, 1931, Abram Kaplan was sued by Matthews and Eggleston, the contractors who had graded the line, alleging nonpayment of $15,000 cash in consideration under their agreement not to bid on the Santa Fe Northern Railroad when it was sold at auction on September 5, 1928. Another interesting fact came to light as the suit was argued. Eggleston and Matthews still held a lien on the railroad in the amount of $75,443.89, that being the value of the grading work performed by them back in 1924. Evidently, Weil had talked them into contributing their labor, but had never gotten around to paying them (Albuquerque Journal - Evening Edition 1931 [May 26]).

George C. Taylor was appointed general receiver of the company on April 2, 1932, just before the line was washed out for the season. He waited until autumn to rebuild the washed out track, thus avoiding the expense of continual repairs during the summer thunderstorm period. Service resumed once more on November 5th. Only a few cars of coal were shipped out, however, before the railroad was shut down due to a lack of coal customers. The last train ran on December 5, 1932. This was, as it happened, the last revenue train ever to run on the SFSJ&N (193 ICC 547).

The SFSJ&N remained idle, but Taylor made one more attempt to breathe life into the moribund property. On April 4, 1933, he applied to the ICC for their approval of a proposed loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation in the amount of $50,000. In his application, Taylor described the condition of the railroad in some detail. There were the two washed out trestles as well as many other washouts repaired with loose dirt and rock. The railroad had no suitable rolling stock, and it had no means of communicating between operating points.

Taylor proposed to spend $10,000 to replace the two trestles and provide flood protection; $12,500 for tie renewal; $5,000 for other bridge repairs; $13,000 for locomotives and a telephone line; and $4,500 for a water supply and other facilities. Unfortunately, the ICC concluded that the prospective earning power of the SFSJ&N did not offer reasonable assurance that the loan would be repaid, and approval was denied (193 ICC 547).

The general decline in the coal market, coupled with the impossibility of train service, appears to have been fatal to the La Ventana coal mines. No further production of coal from the district was recorded following the 1932 washouts (Dane 1936).

It took a long time to bury the SFSJ&N. Nothing happened for years, and the railroad lay idle in the high desert (figure 61). The two SJC&C locomotives remained at La Ventana, slowly deteriorating. Occasionally Charlie Pratt, still Master Mechanic of the SFNW, would journey up to La Ventana to salvage a useful part from one of the locomotives. Once he removed a set of pilot truck wheels from Number 377 for use on one of the SFNW locomotives of the same class (Pratt 1960).

|

| Figure 61. Abandoned hulk of San Juan Coal & Coke Company locomotive Number 2, circa 1938, near La Ventana. |

It was not until 1939, when various creditors made some claims against the company that further attention was given to the SFSJ&N, J. G. Cleary and A. R. Yarborough brought suit in district court for various causes, mostly for payment for services and for reimbursement of expenses incurred during the receivership. The AT&SF intervened in court to enforce their claim of ownership of the rails and fastenings based on the old contract with the Cuba Extension. On April 5, 1939, the court affirmed the ownership of the rail by the AT&SF and approved the other claims against the SFSJ&N (Albuquerque Journal 1939 [April 6 and December 13])

George C. Taylor, who had remained the receiver of the SFSJ&N throughout the years, commented on the troubles of the railroad. He noted that it was subject to washouts when there was a heavy dew, and for that reason his efforts to operate the line with a leased locomotive were failures. He added that creditors of the line had gotten hold of some of its earning, leaving him with no cash to operate the road.

Shortly thereafter the remaining property of the railroad (the right-of-way and the few pieces of useless rolling stock) was sold for $1,000 to J. G. Cleary. And on May 19, 1939, in a final move, the court dissolved the SFSJ&N (Albuquerque Journal 1939 [March 4, April 6, May 20, December 13]).

At some later date, probably about 1941, the AT&SF got around to reclaiming its property along the SFSJ&N line. The rails were lifted and trucked out following a minor skirmish in court with a prospective shipper of cement from the vicinity of La Ventana. There were also several AT&SF coal cars remaining on the line, which had to be trucked out to Bernalillo (Pratt 1960; Albuquerque Journal 1939 [December 13]).

Even after the railroad had all but disappeared, one last bit of bureaucratic tidying up remained to finish the story of the SFSJ&N. During the SFNW abandonment proceeding in 1941, someone remembered that the agreement covering trackage rights between San Ysidro and Bernalillo was still in effect. The abandonment of these trackage rights was approved by the ICC at the same time as the abandonment of the SFNW, October 28, 1941 (249 ICC 342).

The two SJC&C locomotives left at La Ventana remained there for several more years. Various parts had been removed from time to time, and one even lay on its side in the soft ground where the rails had been removed. Finally, during the scrap drives of World War II, the locomotives were cut up where they lay, and the pieces were hauled down to Albuquerque (Pratt 1960).

It had taken the SFSJ&N a long time to disappear, far longer than the period it had actually operated. From the vantage point of time, and in consideration of the dismal production figures recorded for the mines at La Ventana, it is doubtful if any of the investors or builders of the railroad ever received even a token return on their investments.

|

| Figure 62. Looking south from the Anderson Mine near La Ventana. The abandoned road bed of a railroad spur curves from right to left in this October 27, 1973 photo by Vernon J. Glover. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

santa_fe/cultres9/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 02-Sep-2008