|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER XI

Timbe-r-r-r!

Quincy Randles, armed with a master's degree in forestry from the University of Michigan, walked into the Flagstaff office of Willard M. Drake, Supervisor of the Coconino National Forest, one morning in July, 1911, to report for assignment.

Drake was rather short shrift. He dismissed the new forester quickly. "You're going out to the A. L. & T," he said, and went back to his paper work.

Randles turned and walked out into the street. "I didn't know where the A. L. & T. was—or what it was," he recalled. "I ran into some lumberjacks that I knew from up in Michigan. They told me what the A. L. & T. was. (Arizona Lumber and Timber Co.) They told me where to catch the log run, and I went out to the camp. The man that was there when I got there left in about a day and turned it over to me. That was all the instruction I had as to what it was all about. I talked to the foreman and the lumberjacks and a few others and got the lay of the land."

Randles was doing the marking of timber to be cut and such scaling (estimating the amount of lumber in logs or standing timber) as he had time to do.

"We didn't have any scaling manual in those days and no recognized marking rules for ponderosa pine," he said. "You just had to figure out how you thought it ought to be. Of course, I knew something about scaling and that sort of thing. Anyhow, we went on that way. I rotated from camp to camp, doing the marking."

Such was Quincy Randles' introduction to a Forest Service career and long years as Assistant Regional Forester in charge of the Division of Timber Management.

After a short stint in Arkansas, Randles was assigned back to New Mexico in 1913 and while en route visited Juarez, Mexico, just when Pancho Villa captured the town. "We went to the races and had seats about 15 feet from Villa and his staff," Randles said. "Villa was dressed in cowboy hat, no coat and an army khaki shirt. The staff was all dressed up in gold braid. The soldiers, many of them, were barefooted—but all of them were equipped with extra good guns, and a couple of straps of ammunition. Some of them had straw hats, some didn't have hats. They quartered their horses, the cavalry horses, in the stands over there where they used to collect customs, and when they peeled the saddles off of them, the hide slipped with it. There were dead horses all over town. . . .

"I was supposed to stop at Silver City on my way back to Albuquerque and check on a sawmill up on the Black Range. I met Case, the Forest Assistant at Silver City, and we got a car and went to the mouth of East Canyon, and the car broke down. Case and I walked, and got up to Tom O'Brien's sawmill at midnight. We had a piano box to sleep in, back in the backyard. Got up the next morning at daylight and started up to see this sawmill. As I went out the kitchen door, I felt something go 'whoof' in my ear—and I made a valiant leap. It was Tom's pet bear, but I didn't know he was a pet—and the noise didn't sound like a pet!"

After his inspection, Randles went back to Albuquerque to work in the office.

Timber business had picked up immensely, Randles said. "We hadn't any volume tables," he explained, "so I was detailed to measure a bunch of yellow pines and blackjacks and try to get the material for a volume table, which I did. They probably have a better one now, but that was in use when I retired. In the meantime, the appraisal work in the Region was kind of touch-and-go, and they put me on that along with other stuff. There again we had to more or less feel our way because there wasn't any Appraisal Manual at the start.

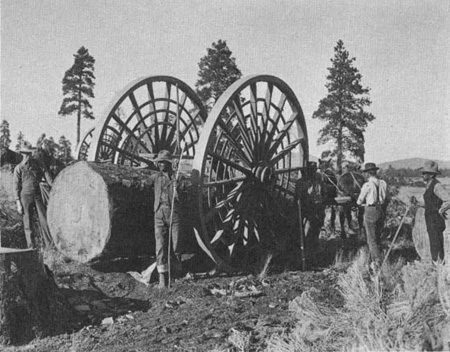

"In those days, the companies weren't very anxious to turn loose any figures at all, but we finally come out with some stuff. It's rather interesting, in those days the average mill-run selling price of ponderosa pine, which included all grades, No. 3, common, and better, the selling price at the big mills was about $13.50, $14.50 a thousand. I haven't seen a figure showing what it is lately, but it must be $70 or $80. Lumberjacks' wages in those days; the best men got $3 a day; the worst of them got a little less than that. But they were good men. All the logging was horse logging, big wheels, and skidding teamsters to bunch logs for the wheels. The logs were taken into the landing and laid out in wonderful shape for scaling. They were picked up with a steam loader, and outside of that, it was just about the same as today."

Discussing the marking of timber to be cut, Randles said the absence of sound marking rules made it rather difficult to get uniform results.

"And we had one other additional problem," he went on. "The railroads were depended upon for transportation from the woods to the mill, and railroads cost considerable money. So the contracts in those days were based on two-thirds cut. Sometimes in the marking we would leave a little more than that, which brought on a considerable squawk from the company, which was logical.

"It was only later that we were required to check certain sections to see whether or not we were holding up our end of the contract by leaving only one-third. The same with the scaling. As I say, we had no scaling manual, and everybody had more or less his own system. But through rather frequent check-scaling we came out with a pretty close result. The logs were laid out on the landing and they were clean on the ends . . . you could see what was going on and our scaling was, I think, as sound as was possible to get it. The company was running scalers all the time to check on the output of saw crews, and they didn't hesitate to check us once in a while. Then this office did some checking.

"Of course, with the collection of the volume of table material we finally got a volume table, which permitted us to do a little better job on cruising of cutover stands than we were able to do before. I'll admit that it always cramped your style a little bit when the published manuals came out, if they varied from what you'd been doing. The result of course was good because it was possible to put on some untrained men, and not rely on somebody who had been trained some place else. In the early days, practically all of our timber sale force were former lumberjacks, and until about 1911 there were no technical men in the woods on sale work. And after 1911 we began to get a few. None of them were very anxious to go into the sales business because it was pretty rough and rugged stuff in those days.

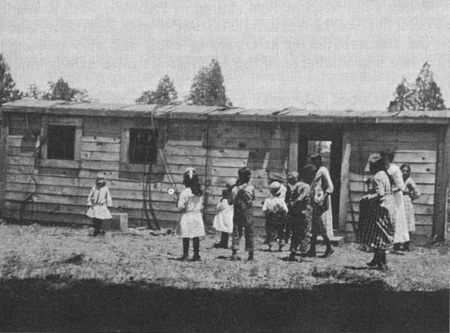

"We had to board at the camps, which was a lucky thing because they had good eats. Sometimes we had to put up tents in the camps because we had no cabins of our own. Finally we got cabins, and the company of course when they moved camp would pick ours up along with the rest. About the only equipment in those cabins, even when we had them, was a little old tin stove, and a water bucket which, of course, we had to furnish, and a washpan and our own beds. Everybody carried his own bed; he didn't take any chances with anything else."

|

| Pemberton's Tie Camp, Pecos River Forest Reserve, 1900. |

Randles related the details of log drives—or rather tie drives—in dry New Mexico, when ties were floated down the Rio Pueblo and Rio Grande:

"The Forest Service entered into a cooperative arrangement to exchange timber lands for timber," he said. "The lands and timber were in the Zuni Mountains and the timber to pay for that land was on what is now the Carson National Forest. Cutting the timber was the Santa Barbara Tie and Pole Company, which cut ties and banked them on the Rio Pueblo and drove them down the Embudo and rafted them at the mouth of the Embudo until the flash floods came, on the Rio Grande. Then they were driven down to the Santo Domingo boom where they were taken out and loaded on a spur, then taken to the Albuquerque Tie Fitting plant.

"In 1912 I was sent to the cutting. In those days we had to go by narrow gauge railroad to Embudo, where I was met by a log wagon at 6 o'clock in the evening. The Company took me over Penasco Hill up to the Santa Barbara Tie & Pole Company headquarters, which was east of Penasco several miles. We got in around midnight. The next morning we got horses and rode over to the top of U.S. Hill, where the company was cutting ties. The Ranger in charge of the sale was Wayne Russell. He had to handle some hundred men cutting ties and, to say the, least, he had more than his hands full. As soon as I got back, I recommended that we send a couple of men up, at least one, to help out. George Kimball was unlucky enough to get elected to the job, and had to work on that sale during the summer. One other recommendation I made, was that the contract with the Santa Barbara Tie & Pole Company was not being fulfilled, in that they were limiting their cuts to ties, whereas the contract called for the removal of sawlogs. As a result of that recommendation, I was persona non grata to the then Supervisor."

|

| Before the day of the bulldozer, logs were skidded by horses. |

Randles noted that logging today is entirely different, with tractor logging and trucking, and conditions for the scaler are much different than in former years.

Probably one of the earliest large offerings of timber for sale in this region was that for 90 million feet of ponderosa pine on the San Francisco Mountain Reserve, now the Coconino National Forest, in 1907.

The file of records on the sale revealed the many problems that confronted personnel in connection with initiating such a large sale without the benefit of previous knowledge of how such stands of ponderosa pine should be cut.

The policy which was to be followed was written by Gifford Pinchot while he was Chief Forester, and was outlined in a letter to T. S. Woolsey, Supervisor, in November, 1906. The letter noted that the aim of marking is to leave enough trees standing to fully seed the ground after logging. Mature timber was to be removed unless needed for seed, and young, fast-growing trees reserved for more profitable later cut.

When Edward G. Miller was Supervisor of the Coconino National Forest the office ran an appraisal of lumber prices around 1920.

"As I recall, the average mill-run selling price was $23 and some cents," Miller said. "The average stumpage price on the Coconino was around $2.00 to $2.50 per thousand board feet. The highest price that any timber brought under bid on the Coconino was on a State sale covering Section 6, south of Flagstaff, 20 north, 6 west—that timber brought $4.00 a thousand. I imagine the boys today would wonder what was wrong, but you could build a very good house back in those days for $2,000. The average wage for lumberjacks in the Zuni Mountains and at the mills on the Coconino was about $4.00 a day and board."

The logging operations in those days were mostly by railroad, and Miller recalled that the bigger operations "like American Lumber Co. in the Zunis, the Greenlaw, Flagstaff Lumber Co. and the Arizona Lumber and Timber Co. at Flagstaff and Saginaw at Williams were all railroad operations." "They used big wheels most of the time in summer," Miller said, "in winter, on snow, they used what they called drays, which were big sleds. Instead of calling them sleds, a lot of the lumberjacks called them drays. Some of the Mormons brought in wagons. The first I saw were, I believe, in 1912 or '13, in the Zunis. Those were contract loggers. The contract loggers and the Flagstaff Company began to use 4-wheel trucks, but those first 8-wheelers seemed to be able to operate on wet ground where some of the 4-wheelers would bog down. Later, outfits like the Arizona Lumber and Timber Company, and the Saginaw, operated their own switch crews, but some outlying tracts they would let to these little contractors. Some people we knew made a living for years by contract logging. Along in the late twenties, about 1927, the successors to the Flagstaff Lumber Company brought in some tractors. The Katy Lumber Company from the South had moved in and taken over the operation. That was the first tractor operation we ever saw. They weren't as successful in the wintertime as the old horses and drays."

|

| Four-wheel and eight-wheel wagons were used in hauling logs, 1924. |

"Those early-day operations had some fine teamsters," Miller related. "Most of 'em had handlers, and gradually some of them worked in to be sawyers. They'd fell trees and buck 'em up. Some of them got to be pretty good men and could take contracts for cutting timber. They got about a dollar a thousand. Some of them, a crew of Spanish-Americans could probably average about $10 a day; they'd cut about 10,000 board-feet. Those northern teamsters were proud of those big teams; they babied 'em, curried them twice a day, and made sure they had water morning, noon, and evening. And in the wintertime when it was cold, they had nice warm barns.

"Incidentally, in those days the farmers in the Zuni Mountains and at Flagstaff depended very largely on the logging companies. I can remember when we first moved to Flagstaff in 1919, those spud-raisers were prosperous. The men who raised oat hay did fairly well. The same applied in the Zuni Mountains. But after the coming of the cat, and the cats made good, the little farmer who depended upon the sale of hay was just about finished. Then came the long shutdowns, due to panics, and even The Arizona Lumber and Timber had to close for a time there at Flagstaff. There just wasn't any sale for lumber. In the good days, in the days when much of the lumber from the Flagstaff-Williams area went into Chicago and that part of the country, it was nothing to see 10 or 15 cars loaded out of one of those towns in a day. Fifteen to twenty thousand board-feet on a car, sometimes heavier timbers would go on flatcars."

|

| "Big Wheels" ready to haul a 16-foot log scaling 1590 board feet to the railroad. |

|

| Unloading "big wheels" at a railroad landing. |

When Fred Merkle, now retired in Phoenix, went to work for the Forest Service, he was assigned to work with Ed Miller, who was then the District Ranger at Guam in 1913, and also assisted Bob Moke who was in charge of the McGaffey timber sale in the Zuni Mountains.

"It developed into quite a sale," Merkle remembers. "They were cutting 25,000 or 30,000 feet of lumber a day."

In 1916, Merkle was put in charge of the sale and moved to the McGaffey mill. "I stayed there at McGaffey until 1918, when I was transferred up to the Santa Fe Forest, to work on the New Mexico Lumber Company timber sale," Merkle said. "That was out on the Coyote District of the Santa Fe Forest. I think that was the year the war was in progress. I was up there alone on that sale—well, I had a scaler. He was a French-Canadian, an old lumberjack—Charles Laller. Of course I had all the marking to do, marking all the timber. They were cutting about 100,000 feet a day. It was at El Vado, out from Durango, Colorado. The company was located in Denver—the New Mexico Lumber Company.

"It was on that narrow-gauge D & RG. It was pretty rough going and it was snowed in part of the winter and they couldn't keep the track open. It connected at Antonito and ran up to Alamosa, Colorado, where it connected with the wide-gauge tracks on into Denver. That year I lived in scaler shacks, they called them. They moved them along the railroad tracks, you know; just picked up the whole rig, family, furniture and all, loaded onto a railroad car. Our living quarters were built for easy transportation—had big old log skids under them.

"That was strictly a horse-logging operation up there. It was different from McGaffey. McGaffey had been using sleds. They used high wheels in the summertime. But the snow was so bad it was difficult in winter, and they used a sledding operation, the front runners of a bobsled. They loaded the front end of the logs on the sled runners and the rear of the logs would drag. On a regular bobsled operation, they would have four runners on the sled—load them up by crosshaul in the woods and drag them in. Now this operation at El Vado was a sleigh operation. They had 120 horses in the barn up there.

"In the spring of 1920, I was moved down to the Pecos, still on the Sante Fe. I had charge of the timber sales there. Had some prop sales for local mining, and two pretty good-sized sawmills up there. H. K. Leonard outfit was up in the mountains cutting up there. I lived at Pecos. I had some mules up on the mountain, across the mountains from Las Vegas—government mules. It was 15 miles from my station to that sawmill, and I'd ride a mule over, get started about 6 o'clock in the morning and cross the Pecos River, ride over the mountains, scale logs, and get back that night. No place to stay there, just an old logging outfit. That's a pretty good day's work. I remember one day I scaled up 350 logs that day. Went over there in the morning and got back rather late that night, around 10 o'clock.

When Edward Ancona was on the Supervisor's staff at Taos before World War I, he used to help out on the big Hallack and Howard Lumber Co. operation in the Carson Forest.

"We had a big railroad operation, something you don't see much of any more," Ancona said. "La Madera had a big mill over there. I guess it was big. It looked big to me in those days. It was a sizeable mill."

Hallack and Howard logged over a hundred thousand acres over a period of eight or 10 years, with limitations on cut and under Forest Service supervision.

Ancona put his finger on the merit of the Forest Service regulations regarding logging when he said that today you can hardly find where they cut:

"I've been there only once since then, three or four years ago, and I went to places where I thought, 'Well, this is where we had a big logging camp.' There was no trace of it, and the timber has grown up and it's hard to see where that big operation was carried on—which I think is a good sample of what you can consider conservative forestry, or farm forestry, in which you expect another crop."

Paul Roberts recalls that the first trucking of lumber out of the Sitgreaves Forest was done by John Zahala from the Standard mill.

"He had two Coleman trucks," Roberts said. "These trucks had hard tires. John started hauling lumber with trucks, and he went to Winslow with it—went down through Holbrook to Winslow. The Goodyear Tire Co. talked John into equipping the trucks with pneumatic tires. Under the deal, they were supposed to keep him furnished with pneumatic tires if John would use them on his trucks. I had a letter from John when I was digging up some information a few years ago. He said he didn't know who got tired first, he or the Goodyear Company, but they had so many blowouts that finally they quit the pneumatic tires and went back to hard tires.

"Jimmy Douglas, the late Jimmy Douglas, who was father of Douglas the ambassador to the Court of St. James in the Roosevelt administration, and one of the promoters of the mines at Jerome, had quite a few interests in the country . . . some, I believe, in lumbering. He was out to see John one time and saw John hauling lumber with trucks, and he said it was the craziest idea he had ever heard of, hauling lumber out with trucks."

Arthur J. "Crawford" Riggs, of Santa Fe, was working on the Sitgreaves in 1928, helping to scale logs and marking timber for the McNary mill logging operation, and he recalls that even with three men working they had a difficult time keeping ahead of the loggers.

"I'll never forget what Jim Monighan told us, that if we scaled as many as 300 logs a day, we could consider that a real day's work," Riggs said. "After the company moved on the Forest and really began to cut timber, if we scaled less than 500 logs a day we thought we were falling down on the job. We had to do it, we had to—to keep up.

"There are some things about that old timber sale that I'll never forget. We used to have to ride—in wintertime we weren't able to use a car to get out to the sale—so we'd ride this train. Of course the Forest Service had no other way at that time for us to get out on the job except by pickup. So we'd ride the train. Many times we left McNary at 6 o'clock in the morning, when it was real dark and 15 to 20° below zero, and try to find a warm place on that train to ride, especially a safe place. You'd ride on one of the cars and you'd freeze to death, even though you might feel a little safer. If the train jumped the track you might be able to jump, but you finally gave that up and thought, 'Well, I'll just take my chances up in the cab with the engineer, I won't freeze to death at least.'

"It was quite an experience. We had lots of snow, seemed like, during the two winters I was there. The second winter I was promoted, I guess, to check-scaler, and did mostly check-scaling and cruising, and some survey work. Bill Beveridge and I stayed out in a camp, oh, about 20 or 25 miles north of McNary. We got snowed in during the winter and couldn't get out for about two months. We couldn't move our cars from this ranch house where we were staying. The railroad track was about a mile from the ranch house, so we were stuck. If we wanted to go to town, we'd have to catch the train. But we had a lot of fun and we cruised a lot of timber, all on snowshoes."

|

| In the early days, railroads played an important part in the harvesting of timber from the Southwestern National Forests. |

The railroad logging operations continued through the winter. The logging company skidded their logs onto landings along the spur railroad track that connected with the main line to McNary.

"They did their skidding with these old cats—the Caterpillar 90, I believe they called it," Riggs explained. "They were real good machines for that time. What would irritate the scalers considerably was that you'd get on a spur where they skidded in a lot of logs, and scale those all up and figure, 'Well, I've got it made now. I won't have to worry about getting behind on logs.' Then here would come a woods foreman and say, 'How about comin' over on this other spur and scalin' some logs? We've got a whole trainload of cars over there we'd like for you to scale.' Well, we did that for quite a while. We humored them and we'd get over there and work ourselves to death to keep ahead of the loader, loading out these cars.

"Then, finally we got wise to ourselves and we told them they'd load where we had the logs scaled, instead of having us chase all over the woods.

"I remember one incident. I had scaled a landing of logs one afternoon before going in for the night. Six or eight hundred logs were along this landing, a good trainload of logs anyway. Next morning I stopped at a place along the main line where they had skidded in a lot of logs and started scaling there. In about 30 minutes, here comes the woods foreman riding the log train. He ran over and said, 'I want you to come over to this other landing and scale some logs.' I said, 'You have a landing of logs back on this other spur.'

"He said, 'Well, I want to clear out this one over here.' I said, 'Well, you'll just have to wait until I get these scaled, and then I'll go scale those.'

"He made some remark about seeing my boss and reporting me to the Forest Supervisor. My marking hatchet was sticking in a log pretty close by, and I nonchalantly walked over and jerked this axe out of the log and stepped toward him. I had no intention of using it. So he spoke up—he got a little bit excited—'Now, wait a minute . . . wait a minute, Mr. Riggs. We can take care of that all right. Don't worry about it. We'll get along all right.'

"So I wasn't bothered then after that, about scaling any logs. And he didn't report me to the Supervisor. But, that's the way it went."

Jim Monighan spent several months in McNary in the winter and spring of 1927-28, and he discussed experiences similar to Riggs' concerning the railroad logging operation.

"The logging at McNary on the old KD Lumber Co. sale was strictly a skidding proposition when they first came on the Forest," he said. "They used chokers around the logs, skidding them directly into the landing where they were unhooked. The loader lifted them and put them on the cars, and they were taken into McNary every night. This type of logging in the early days, before we made many plans, really chewed up a lot of the soil, and made deep gouges from the logs being towed directly on the ground. In a good many places, it did make a good seedbed and in many areas where we had done this kind of logging, we got excellent reproduction in good years when we had good seed crops.

"One interesting thing about this old sale was the marking along the county road that went from McNary to Vernon. When we first started marking timber around Lake Mountain and along this road, we left a strip—I believe it was 200 feet wide on either side of the road—where there was no marking whatsoever. We left it in its natural state. Shortly afterwards, maybe within a year or so, the policy was that you could take out decadent trees and lightning-struck trees and trees that you really thought were going to die within a short period. Then after that you could mark about 30%. The policy changed again and you could mark 50%, and shortly afterwards, the policy changed again and you couldn't mark anything. As I remember, when the sale closed out, or just before it closed out, you could do the same type of marking along the highway, on this county road, as you did on other areas surrounding it.

"After the winter, spring, and summer at Los Burros we were finally moved into cabins that the Forest had built on Indian Service land in McNary, or just outside the town limits. We moved into the cabins there. Marge and I had two cabins that were about 8, 10 feet apart. We had a bedroom in one, and a kitchen, office and everything else in the other. The john was an outside john. Water was piped in from the town of McNary and we did not have flush toilets.

"We spent the winter of '27 and the spring of '28 in McNary, at which time, in the spring of '28, I was offered the timber sale job on the Grand Canyon unit, which is now the Tusayan Division of the Kaibab, as timber sale man. We reported in the spring of '28 to Williams. We lived in Williams for several months while George Kimball, Arthur Gibson, John Schroeder, and a few more of the boys on the Tusayan that could drive a nail, built us a house. As I recall, it was 20 by 20, and divided into four rooms which were about 10 feet square, which didn't give us too much space. The headquarters logging camp for the Saginaw was on the Santa Fe Railroad, halfway between Oneida and Grand Canyon. Our water was hauled into the camp in big tank cars from Williams and put on a siding. We had two 8- or 10-gallon galvanized buckets and we had to walk 400 yards or so, and turn the water on in the tank and get a few buckets of water. It took a long time to get down there with a few buckets of water to fill the tub that we put on the old wood stove to heat water, so you could have your Saturday night bath.

"During the early days of the Grand Canyon sale, we were not furnished with a car by the Forest Service, nor did we have a speeder to run on the Saginaw Railroad tracks. The logging train would leave the headquarters camp with the empty cars between 4:30 and 5:00 o'clock. We had to get on a car and go up to the logging camp and then walk out to where we were marking trees or supervising the brush, or skinning the logs, or doing the other jobs that were necessary around a big logging operation. Then we came back in with the loaded cars at night. We'd get home anywhere from 6 to 8:30, if the cars stayed on the track. And if they didn't, it might be midnight, or the next morning, before we got home. We did this for months. I recall that there were a couple of the assistant scalers' wives came up to our house one day and just chewed into Marge and gave her the devil for me taking their husbands away from them for so long every day in the week and not getting them home 'til way after dark, and taking them to work before the sun ever thought of coming up. Marge listened to it as long as they wanted to expound, and finally she says, 'Well, doesn't Jim go with them? He's not at home, so he goes with them too.'

"A short time after this incident we did get an old Model T roadster that had belonged to the Supervisor's Office in Williams. When they got a new sedan, or a new pickup, I believe it was, we got the old Model T roadster. We didn't have to leave home until about 6:30 or 7 to get up into the woods in the Model T. But on the days when it was muddy or snowy, you'd still have to ride the train. A little later, we got a motor scooter to run on the railroad track to take us back and forth to the woods. These scooters were very, very treacherous. The railroad tracks had these high joints. They're not smooth. The curves aren't good. If you're not careful, if you got up too much speed, the scooter would be just as apt to leave the track and throw you off and skin you up. Several times, in riding the scooter, we'd be thrown off and get skinned up, but then get right back on again because that's the only way you had to get around.

"The logging operation there was two-fold. First, they skidded entirely with horses and high wheels. This went on for a year and a half, then they went to skidding on the ground with cats, and after a while they went to arches, steel arches with a track on either side, instead of wheels. They'd lift up the front end of the logs about 6 feet off the ground and take 'em into the landing where they were dropped and loaded onto the cars and taken to the Santa Fe Railroad and then into Williams. On their outlying areas that they considered too scattered to log, they had a contract they gave to an old fellow by the name of Pat McCoy and his brothers, Jesse and Zinny. They were quite an outfit. They were hard workers. They used 8-wheeled wagons pulled by horses. They'd just skid them up into a wagonload in the woods and they'd cross haul; load by crosshauls, and then take them to the landing. They were paid so much a thousand. They did all the work on these outlying areas, the cutting and the swamping and the brush disposal work, and getting the logs to the landing. The McCoys were good contractors and they knew their business, and they knew what the Forest Service regulations were. Though there were times when we might have a few arguments with Pat, why, they were just honest arguments, things that he believed in."

|

| Saginaw and Manistee Lumber Company's sawmill at Williams, Arizona, had a capacity of 200,000 board feet per day. Photo taken in August 1919. |

Monighan remained on the Grand Canyon unit until the latter part of 1933 when he was assigned to the Williams office. In early 1934 he was promoted to Assistant Supervisor, then later served as Supervisor on the Sitgreaves and Cibola National Forests prior to retirement in 1963.

Norman Johnson, of Flagstaff, spent 27 years on the Coconino National Forest in timber work and likes to recall that it was often said that "the Coconino trains most of the timber-sale boys in the Region." While not true nowadays, for awhile it was just about the situation.

"We got two to four new men just about every season," Johnson explained. "Sure there were exceptions during the War years, but there were a lot of boys comin' through the timber camps on this Forest. Of course there have been a lot of others who've had a hand in the training of these men."

Johnson said that he had a few failures, but wouldn't call them failures. "I would say this," he went on, "they just didn't fit. This brings to mind something that will let you know that your bosses sometimes realize more than you think they do about what's goin' on. If you get four new men a year, you'll get one out of the four who's above average, two average, and one below average. So, naturally with myself as the trainer of these men, when they ask for my recommendation when it was time for them to move on, naturally, I'm gonna recommend the man who has made life easier for me, who is generally the better man of the group. So he goes first, and then the average fellow, and that leaves the lower-than-average. When this happens for a few years, what do you wind up with? It actually happened that way here on the Forest. The Supervisor came out and talked to me and said, 'I realize what's happening, but don't know what to do about it.' There was a build-up of a force of men that were below average. They were all good fellows, nice to have here in camp. Their greatest failings were that they couldn't do things with their hands. I think of one who was raised on the streets of New York. He couldn't even open a gate. What help was he to me? Oh well, he could do the leg work—if I told him which tree to mark, why, he'd go ahead and mark it. He did save me some leg work, but he just didn't fit. So I'd say we didn't have failures; we just had fellows that didn't fit."

Gordon Bade, of Williams, who retired from the Forest Service in 1958 to become a practicing consultant in forestry, believes that a better job of technical forestry was accomplished on project sales in past years than today.

"We had a trained timber crew that did nothing but handle timber," Bade explained. "They got a better job done, and I think more efficiently than today when it's under the District Rangers who seldom see the sale. The job of forestry is assigned to temporary, green people, untrained people."

Bade went on to say that project sales were handled by "practical foresters like myself, Lafe Kartchmer, Carl Johnson, Homer German, John Churches, Paul McCormack, and of course, Norman Johnson."

Bade speaks as a timber man and in presenting his ideas on timber management thinks "we should encourage more technical foresters to follow the timber management profession."

"Of course," he said, "in this Region, it's all range. I've had young fellows working, junior foresters, who said, 'Well hell, we want to get into range management so we can get somewhere.' That's wrong in my opinion. Our major resource is timber. As a matter of fact, special use fees are about to catch up or pass grazing fees. Put it on an economic basis."

Like Monighan, Gordon Bade had problems with transportation in the woods. "There was the time when Ed Groesbeck and I were scaling right-of-way logs on the Sitgreaves out of McNary," Bade recalled. "We had a little railroad speeder. The railroad tracks they built in those days weren't fit to walk on, let alone run a locomotive over, or a speeder. We would scale a bunch, then start the speeder up and go up for the next batch. We were going up this steep grade and we didn't make it. The speeder just didn't have enough power to do it. So we rolled back down and I says to Ed, "Shall I cock her back?" He said, "Yeah, cock her back; give her hell." So I cocked her back, and going up this big hill, up this steep grade, we came to a cut and the expansion had pushed the rails down. The steel crew had done what you never should do, they had joints opposite instead of staggered, and it just made an angle bend in the track. I saw it, and I said, 'Hold it, Ed, we're going to jump the track!' I knew we couldn't get around that sharp turn and, sure enough, we left it. I turned a somersault over the top of the thing and I come up, kind of stunned, and when I came to, there was Ed in agony. He had broken his leg.

"I had a job getting the speeder back on the track, and Ed back on the speeder, and tying his leg up with my belt, my shoe strings, and lunch box strap and getting him on the running board of the speeder and taking him down the country. Then we had the problem of running into a log train, moving empties out backwards. Kind of scary. We got down to the foot of the hill and we found a sedan there that I knew was with the survey crew—a company crew running out railroad spurs. We located them and they took Ed to the hospital by car. He was laid up quite a while with that.

"We had quite some experiences on those railroad speeders. Got some scarred heads to show for it. Once we pitched Bob Salton off head over heels. The gauge would vary so that the wheels would drop in—so would the locomotives. I've seen five locomotives on the ground at one time. That was no way to log.

"Another time we had a locomotive off. We were plowing snow. We had a home-made snow plow. Speed was the criteria, you know—you had to get up speed to push the snow. I felt the ground kind of rough under me, and I looked at the engineer and said, 'What happened?' He said, 'We're off.'

"We had run out into the woods about 50 yards. The ground was so hard that the drivers didn't sink. We just jacked the damned thing up, built a track under it, and ran it back on again. That took a couple of days."

|

| Portable schoolhouse at the Greenlaw Company's logging camp, Coconino National Forest, July 7, 1920. |

Edward Groesbeck, of Albuquerque, was assigned to timber sales on the Coconino Forest in 1937. His experiences were typical of timber staff men.

"We were cutting quite a bit of timber when I went there," Groesbeck said. "The A.L. & T. was cutting. The old Southwest had the Rock Top and the Sawmill Springs units under contract, but they closed down at the first of the Depression. In 1927, I believe was about the last time they cut there and they were closed down for about 10 years. They didn't open again until about 1937. They opened up and started cutting again out there at Sawmill Springs. The old Flimflam Railroad was still in place there and they worked out a joint agreement with the A.L. & T. to where they used one railroad instead of maintaining two railroads running parallel right down through the same darned country. The old Flimflam track they pulled that out and junked it while I was there, and actually it was the old Southwest Railroad that they operated. Then they extended the railroad from there on up into the Rock Top unit and down as far as Allen Lake, and that's where this thing still is."

In November and December of that year, Groesbeck recalled that he marked out two million feet of timber in the Big Springs District out of Williams.

"I was running back and forth to Williams trying to keep track of that stuff," Groesbeck said. "There was no place to live. The old Jacobs Lake Ranger Station was there, but there was no water. The well had caved in, gone dry or something. The only place to stay was Jacobs Lake Lodge. They closed down the first of November, but they had old Devereau Bowman up there, kind of watching things. I'd stay there with old Devereau. The darned guy didn't like to get up in the morning until about noon, and then he didn't like to have supper 'til about 10 o'clock at night. I'd get a big hunk of bread, and in the morning that was all I had for breakfast. No coffee or nothing. I'd go out and mark timber 'til noon and then come in and get my breakfast and dinner combined with old Devereau. Then I'd come in at night and the darned guy—come supper time he liked a drink of wine. We'd have to drink about four bottles of wine, and by that time it'd be 10 o'clock, and we'd have a good supper. He'd really cook up a good supper. But breakfast was a bad deal; I didn't get any breakfast at all. By gosh, you know, when you're wading that darn snow out there all morning a fellow needs a little food to keep soul and body from getting too far apart. They were sure long mornings, I tell you.

"Along early in the year sometime the Whitings had that sale and they decided to put a mill up there. When I went there the timber was going down to Glenn Johnson's mill there at Kanab. They built that mill there at Orderville.

"Then we made another sale to the south that we called the East Fork unit, and then we worked out a cruise on the old Fracas unit in Fracas Canyon, in that area, and also the Big Saddle. We made a sale over on the Little Mountain. That was sold and they started in cutting pretty earnest, and they finally built the mill down there at Fredonia and got pretty well set. The big sale unit was just ready to go about the time I left the Kaibab.

"I left there and went to the Apache. But I had the cruise made and got the sale ready to go. They finally put it up the next year. That's the one they had all the fancy bidding on. Sold at $44.10 a thousand, which was one devil of a price. When you stop to think that the whole Kaibab timber had been offered for sale somewhere around 1910 or '12 for a dollar a thousand, and then in that short time—that sale was made at $44.10 a thousand. Nobody had ever paid a price like that for timber in Region 3. You know, they thought that was kind of a screwy thing, but you know that E. I. Whiting was a pretty sharp fellow. His contract covered an estimated 168 million feet, as I remember it, of which 15 million feet had to be cut at the bid price, and with reappraisals at 3-year intervals. Well, I think the timber was advertised at around $7 a thousand, or something like that. That old boy was pretty sharp, you know, he was bidding for position and he wanted that sale. It required that he build a mill down there at Fredonia, and cut 20 million feet of timber per year. Anybody looking at that 15 million feet at $44.10 a thousand, why, it was quite a jag of money, all right. But the old boy was smart enough to know that when time for reappraisal came along, why, the price wasn't gonna be that. It'd be back down. He was actually thinking, I'm sure, 'We're willing to buy timber at the price of the Forest Service appraisal plus so much a thousand over the total amount.' He was paying a premium on that 15 million. Now you take that money and distribute it over the whole 168 million, you know it'd only made $2 or $3 or so above the Forest Service appraised value. But of course he had to have a few bucks salted down to pay that first jibe. They had it, but you know, that was a pretty stiff poker game those rascals were playing when they went in on that stuff.

"The Whitings and Southwestern got to battling, you know, when Buck Elmore was vice-president in charge of operations there at McNary. He was kind of a rough-shod old boy. They got to squabbling with the Whitings over there on the Apache on some of those sales. A sale would come up for the Whitings, why, old Buck would get over there and he'd run 'em up. He'd run 'em up to about $35 a thousand on one of those units.

"Another sale on the Sitgreaves, down around Pinedale, he jumped in an' run 'em up there pretty high. At Cox Canyon unit, on the Gila, he ran that up to $16 a thousand. Mr. Whiting was getting kind of irritable about it. Bucky failed to remember, by gosh, that they were gonna have units of their own coming up some day. One of these units did come up on the Sitgreaves, I guess it was on the Heber District. Bucky woke up with a heck of a start one day and remembered that he had a unit coming up, and he thought he'd better go over and patch fences with Mr. Whiting or he's really gonna make 'em pay for this timber. So he called up Art Whiting, E. I.'s brother, and told him he realized they'd put over some pretty sharp deals but he'd kind of like to bury the hatchet.

"Well, sir, you know, it was a funny thing. Whitings had had a deal with the Southwest that they would cut a couple of million feet off of the old P83 Forks unit, a deal that was made years and years ago. Bucky Elmore was about to cancel that deal out and kick them off of there. They needed the timber themselves, and they were about to terminate that thing. But someway or other, along about that time they had a change of heart, and Whitings kind of increased their cut there. They got four million feet a year instead of two off of that Rock Top unit. They run that Alpine mill and part of the Eager mill for quite a long time off of that extra timber they got from the Rock Top unit, off of the Southwest lumber mill sale. When the Southwest sale came up apparently the Whitings didn't bid on it at all. But it was kind of interesting that they happened to get all this extra timber off of the P83 Forks unit just about that time."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap11.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008