|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER X

Reconnaissance

Raymond E. Marsh, a Yale Forest School senior, was completing his field work in Louisiana in the spring of 1910 when he decided to take the Civil Service examination for Forest Assistant in the Forest Service.

Notice of appointment came through in June after, as he put it, he had fled to Illinois "to escape the enervating heat of Louisiana."

"As a northern boy, I had not become inured to it, nor to the rampant ticks, chiggers, and water moccasins, to which one living in camp and working in the woods was especially exposed," Marsh wrote in some memoirs* recently.

*For the Oral History Office of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, California. At the time he prepared these notes he was living in retirement in Washington, D. C.

His appointment as Forest Assistant, effective July 1, 1910, instructed him to report to the Headquarters of Region 3 at Albuquerque. He had been attracted to Montana and asked to be assigned there, but the assignment was to the Southwest. Although he had not been pleased with the location of the assignment, he accepted and "became very fond of the Southwest." He did not leave until 1926, and then "with some regret."

When Marsh arrived at the Albuquerque office of the Region 3, he met a group of men who were destined to become important figures in the U. S. Forest Service. A. C. Ringland, the Regional Forester, went on to a distinguished career in Washington. So, too, did Associate Regional Forester Earle H. Clapp who became Acting Chief Forester (1939-1943). T. S. Woolsey, Jr.,** scion of a noted Yale family and himself a Yale Forest School graduate, was Assistant Regional Forester for Forest Management, and his assistant was A. B. Recknagel.

**Woolsey left the Forest Service a few years later and had a tragic death, as a suicide, according to Marsh.

"Recknagel informed me that I was to join the timber reconnaissance parties already at work on the Apache National Forest," Marsh*** recounted.

***Marsh, too, had a distinguished career, going up through the ranks to the position of Assistant Chief Forester.

After a journey by train to Holbrook, then a two-day trip by stage and transfer to a light spring rig, Marsh reached Springerville, only to transfer again to a freighter wagon headed for the camp of the reconnaissance party more than 40 miles farther south in the Black River watershed.

Aldo Leopold was chief of the reconnaissance party, succeeding J. Howard Allison (now Professor Emeritus, University of Minnesota.) A year or two previously, a systematic program of taking inventory of timber resources had been started on the National Forests. Called timber reconnaissance, the purpose was to obtain information for timber management and sale policies. The first party in Region 3 began work on the Coconino, the most important timber sale Forest, in April 1908. Allison was the only technical forester on this reconnaissance, and served under Frank Vogel, "a well-known, tough, able woodsman, who had gained an enviable reputation as a timber cruiser," according to Marsh. When Vogel was transferred to Colorado, Allison took over and soon was made technically responsible for the work in the Region.

Marsh described a typical field party as including the party chief, usually a graduate forester, Forest Assistants, forest school students, an occasional lumberman or Forest Ranger, a cook, and a horse wrangler—10 or 12 men in all. Later some parties also included a draftsman to make preliminary maps and sketches.

Members of the party enjoyed the luxury of sleeping on army cots, for the parties were moved by wagon every few days, and double and single tents and a large cook-eating tent were set up.

The work of the cruisers included estimating the volume of timber and describing its character on each 40-acre block, with sketches to show natural feature, culture, forest type boundaries, and topography. Elevations were obtained with an aneroid barometer.

"Each cruiser worked alone," Marsh related. "He carried a Jacob's staff, the staff compass on his belt, an aneroid barometer, and a hand counter for counting paces. He carried a light lunch in a large handkerchief fastened to his belt, and in dry localities a canteen with drinking water slung over his shoulder."

In making his reconnaissance, the cruiser started from a known section corner, and getting his direction from the compass and the distances by pacing, "he walked through the three-mile row of outer forty acre areas, tying in at each mile with a section corner." He then turned around and came back through the center of the adjacent row of 40-acre blocks. This was equivalent to six miles of cruising line, or one and one-half sections for the day.

|

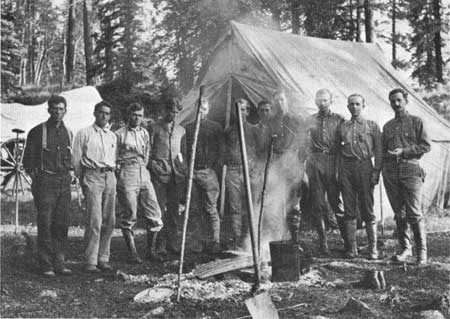

| Timber reconnaissance party in camp, Apache National Forest, July 26, 1910. Left to right: Lonnie Prammel, R. E. Marsh, H. H. Greenamayer, J. H. Allison, C. W. McKibbin, G. H. Collingwood, R. E. Hopson, H. B. Wales, J. W. Hough, Aldo Leopold, and John D. Guthrie. |

"The cruiser estimated the volume of sawtimber on a 40 by the (Frank) Vogel method," Marsh said. "This was to calculate the volume on one or more sample acres or fractions, expanding this to a full acre, and in turn to the 40."

Marsh reports that there was little opportunity for recreation, though some camps were near a trout stream, and game was plentiful.

"We tried to inject a bit of humor by pretending to bury the cook, whose biscuits we thought were too heavy," Marsh related. "This was done with much ceremony—the grave marked with stones and many flowers, and the mourners lined up beside it, registering internal discomfort."

|

| The timber reconnaissance party figuratively buried the cook, whose biscuits were heavy, with flowers and exaggerated humor. Left to right: Aldo Leopold, Harris Collingwood, Hopson, McKibbon, O. F. Bishop, J. W. Hough, Basil Wales, J. H. Allison. |

Another interesting highlight was an overnight visit from Deputy Supervisor Fred Winn and his new bride "a concert or opera singer of high repute in Paris," Marsh said. "They were a gifted and entertaining couple. For years afterward, Mrs. Winn sang on many important occasions in the Southwest. Fred pretended not to like being called Mr. Ada Pierce Winn."

After a couple months of reconnaissance, Aldo Leopold took the technical members of his party to the Apache Rangers Meeting at Springerville, September 8-14, 1910.

During one of the sessions, Leopold made a talk on reconnaissance, describing in detail how his party operated.

"The area covered last year was 65,000 acres," Leopold reported. "The area covered to date is 170,000 acres. Two hundred thousand acres remain uncovered. Cost of the work last year was four cents per acre—this year one and two-thirds cents, and at the rate we are going, by the time the work is finished, the cost of the work may be reduced to one and one-half cents."

Leopold also told the Rangers of "the fine crew of men" working for him during the summer—Yale and Michigan men, some graduates.

"By the reconnaissance system, a green man can do surprisingly accurate cruising," he said, and went on to explain the method of training the men to do accurate pacing in measuring distance.

Leopold's party continued the reconnaissance on the Apache National Forest until driven out by snow in November. After an assignment on the Lincoln National Forest (then called the Alamo), Marsh was assigned to another reconnaissance party on the Carson National Forest for the summers of 1911 and 1912. The reconnaissance party and operations were typical of the Apache cruisers. One of the cruisers on the Carson was Harvey Fergusson, who in later years became a famous southwestern novelist. He was then a student at the University of New Mexico, working at a summer job between semesters.

Marsh related that later on when he was Forest Assistant on the Carson, Earl Loveridge was assigned to do a one-man timber reconnaissance of two months duration of the distant Jicarilla Division.

"He was his own cook and camp mover," Marsh recounted. "His camp was broken into, robbed and food stolen, and he worked under much difficulty. He went without mail for five weeks. This assignment would not be considered reasonable under the criteria of later years. As Forest Supervisor, I, no doubt, shared with the Regional Office responsibility for it. Loveridge did the job. He displayed boundless energy and devotion to duty that characterized his Forest Service career, the last twenty years of which he was Assistant Chief for Administration."*

*When Loveridge died, he was cremated and his ashes were scattered over the Pecos Wilderness—"the wild and beautiful land he loved."

Reconnaissance was difficult and often disagreeable work, as were other phases of forest activities in the early years.

Ray Kallus likes to tell this story about Ralph Hussey and Landis (Pink) Arnold:

They were making a land classification on the Santa Fe National Forest in the early days. They ate their meals at the Harvey House, and had some kind of a shack that they rented in town and were sleeping there. They spent their time, of course, in the field. One morning Huss got up and put on his clothes and shook Arnold, but didn't say anything, just made him think it was time to get up. As he walked to the door, Pink wasn't ready yet, hadn't got his clothes on, and Huss said, 'Well, Pink, you're just too slow, I can't wait for you.' So he went on out the door and in a few minutes, Pink came out. Huss went on around the house, came on back in and went to bed. Pink went on down to the Harvey House ready for breakfast. He ate breakfast, drank a cup of coffee, and was wondering where the heck Huss had gone to. He ordered another cup of coffee and, finally, with his third cup of coffee he looked up at the clock and saw the time—2:30 a.m. That Hussey was always pulling stunts like that."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008