|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER IX

Grazing Problems

Ranger Henry Woodrow offered a simple solution for Rangers who had problems with grazing permittees—if they were widows, that is.

"There happened to be a widow on this part of the District (the McKenna Park District of the Gila National Forest) with a grazing permit on the Forest and a ranch near the Gila Ranger Station," Woodrow said. "So I married her. . . . Later I heard of Rangers on other Forests and Districts having quite a bit of trouble with widow permittees.

"I would suggest that the Forest Service put a single man for a Ranger there, and probably he would marry her and stop all the trouble."

Unfortunately for single Rangers elsewhere, many of their problems were with male permittees.

Edward G. Miller had hardly moved into his new position as Supervisor of the Prescott National Forest in April 1917 than he was faced with the problem of handling a "hot potato."

Early one morning a man appeared in the Prescott office, introduced himself and was all smiles for a few minutes. It was not his name, but we'll call him Mr. Perry.

Without any preliminary warning he addressed the new Supervisor, "Young man, you bear a wonderfully fine reputation, but if things don't change you're going to be fired."

Then Mr. Perry went on to spell out the doleful things that had happened to a U. S. judge who had found him guilty of land fraud and sentenced him to Federal prison, and what had happened to one or two others. All had suffered injuries or afflictions of some kind that were imposed by the Almighty due to the fact they had been "unkind and unjust in their dealings" with Mr. Perry.

Then Mr. Perry got down to the business of the day. He had bought around a thousand head of drouth-stricken cattle in southwestern New Mexico and he proposed to graze them on the Walnut Creek District of the Prescott National Forest. He claimed title to forty-acres on which a spring was located and felt that since he owned that water, he should be allowed to bring cattle on the District, even though it was already fully stocked—in fact, parts of the District badly overstocked.

Supervisor Miller, unimpressed by the story of the dire consequences of opposing him, informed Mr. Perry that there was absolutely no chance of his getting a permit to graze a thousand head of stock—or even a fraction of that number—on an already overstocked range.

Mr. Perry then announced that he would "appeal on up the line," and was advised that was quite satisfactory with the Supervisor.

A short time later, Regional Forester Paul Redington, accompanied by the Chief of Grazing and one of the grazing men from the Washington office, arrived by train at Ash Fork and were met by the Supervisor and Ranger Fred Haworth of the Walnut Creek District. They visited the range with Perry, then went to Seligman and sat down and argued the case for a day.

"Of course Mr. Perry did not get his grazing permit," Miller said. "Regional Forester Redington had sized up the situation almost exactly as did the Ranger and Supervisor."

Talking about the history of grazing in the Coconino district where he was Supervisor for sixteen years, Miller said that in the late 1880's and 1890's when Camp Verde was still occupied by the U.S. Cavalry, "too many cattle were brought into the country."

Miller went on, "Jerry Sullivan and George Hance, who were soldiers and later became stockmen, told me that several times the number that the ranges would carry were brought in. No one knew about carrying capacities then. They were brought into that country because of the mild winter climate, and because they figured with the troops there, their cattle would not be molested by the Apache Indians. While the troops were there, Indians with hoes would go out and cut the grass, particularly the fine grasses like Porter's muhlenbergia, locally called Black Grama. The sod was practically killed over a large area. Those Indians would cut the grass, dry it, and sell it for hay to the troops, to the United States Government. The big drouth came on and, according to both Hance and Jerry Sullivan, you could ride anywhere out from Camp Verde, particularly to the east, and be in sight of dead or dying cattle continuously. I thought, after going over that range in 1919, that it would be possible to bring a lot of that country back within 25 years. After spending 16 years on the Coconino, it seemed safe to predict that several decades, maybe a hundred years or longer, will be required to bring the ranges back to the conditions that existed when the white man first came in with his cattle and sheep.

"One of the first moves that I think helped the country east of the Verde River was to divide the cattle ranges into summer and winter allotments. Those winter allotments had the summer growing season with very little stock to eat the grass. We thought that in a short period of four or five years, that we could see considerable improvement."

|

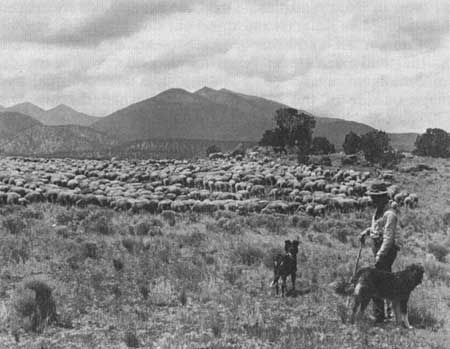

| Closely-herded sheep quickly damaged already marginal range—1914. |

Miller noted that another grazing problem on the Coconino that developed in the 1920's was control of damage by livestock to yellow pine reproduction. Miller said, "There were millions upon millions of little pine seedlings. Research men were keeping a close watch to see what happened, and some of the boys felt that by 1923 excessive damage was being done by sheep to the little trees. One or two of the researchers openly recommended exclusion of sheep from the yellow pine country, at least on the cut-over areas, until the pine seedlings reached a height where sheep damage would be negligible.

"So-called individual sheep allotments had been in existence for a number of years, but unfortunately cattle were not excluded. Actually those allotments were dual-use allotments. We proposed to separate the two industries, cattle and sheep. Col. Greeley, with his chief of Grazing, along with the Regional Forester and our Chief of Grazing, came out and we held meetings at Flagstaff during the early summer of 1925. The sheepmen agreed to have the Forest Service fence National forest boundaries and to help build the interior fences that would divide cattle and sheep."

Miller said that the group argued over sheep reduction and decided that it would be unfair to make heavy reductions overnight. The thing to do, it was argued, was to divide the ranges on an individual basis as far as practicable, then allow each permittee to see what numbers he could graze without serious damage to yellow pine reproduction.

"Local Forest Officers had spent a lot of time following sheep and cattle around," Miller recounted. "They found that under certain conditions in June, particularly where water was scarce, old cows, and some younger animals, did a lot of damage to reproduction. So did deer; so did antelope. Squirrels liked the tender seedling buds; so did mice. Within a few years we found that the sheep ranges were making much more rapid recovery than were the cattle ranges, because the sheep could be controlled more easily. They were constantly under the control of the herder. Some reductions were made in both cattle and sheep numbers, but unfortunately old Mother Nature had a way of stepping in. We had an exceedingly dry year over parts of the Forest in '26, even in some of those plots that were fenced in 1912. Considerable grass sod dried out due to drouth below.

"Cooperrider and other research men found that in several plots that had been under fence for a good many years, death from drouth, mice and other rodents, was almost equal to the damage outside of the plots. Of course when the big drouth of '34 came on, hundreds and hundreds of cattle were shipped out of Flagstaff and other shipping points. A lot of 'em came up from the Tonto. Poor wobbly old cows. Even the stockmen who had claimed that this grass would be all right if it ever rained had to admit that animals had to be moved or they would die just as cattle had died back in the nineties."

Jesse Nelson, who was the first Ranger on the Yellowstone Forest Reserve, later became Inspector of Grazing in the Washington office and served as an Inspector of Grazing in Region 3. With the help of Will C. Barnes and Leon Kneipp, he was instrumental in putting across the grazing regulations with livestock men in the Southwest, according to Paul Roberts.

Roberts attributed some of the grazing problems of the 1920's to the extra burden put on the ranges during World War I and immediately after when the livestock industry hit a depression. Ranges were overstocked and cattlemen could not sell their livestock.

After a reconnaissance on the Sitgreaves National Forest in 1916, Roberts devised a program for a grazing plan for each individual allotment. That system was later adopted.

Discussing the problem of cattle and sheep on the same range, Roberts said it did not cause as much conflict in the Southwest as in the northern areas.

"They had some sheep and cattle war-type incidents," Nelson said, "but they never had the intense sheep and cattle wars in New Mexico and Arizona that they did in Montana and Wyoming and a part of Western Colorado where the sheep moved in. Up there the sheep moved in on an established industry. But down here, sheep were in New Mexico long before cattle."

Another of the men who were influential in establishing the grazing program. was John Kerr, the old-time cowman, who had served as a Ranger, Inspector of Grazing and Chief of the Grazing Division of Region 3. "The stockmen all liked John Kerr," Roberts said. "John was very fair. It was an inter-developmental time, and nobody knew anything about the grazing capacity of the ranges. The first job was to really make some kind of reasonably fair distribution of the range on the Forests between the old prior users, and get them located on allotments. But sheep—sheep went everywhere. They didn't have any allotments. They had to get them tied down some way, and that was the big job for a good many years. As a matter of fact, they didn't establish allotments in a lot of places for several years after the Forests were established. Permits were just issued on a numbers basis. They established the number as best they could by prior use, by what people had run there before. That was pretty feeble in many cases. The numbers we could establish any prior use for were far beyond any reasonable carrying capacity of the range.

"I can remember we were having a big fight over the seedling damage, and it was really tough. We were under a tremendous amount of pressure. H. H. Chapman was taking a year's sabbatical leave from Yale. He was Chief of Silverculture, they called it then, in Albuquerque that year. I remember one afternoon he came in and was talking to John about sheep damage, and of course Chapman was hell-bent on getting rid of all the sheep. Old John would never talk during the day, but along about 4 o'clock, when we quit in those days, John would lean back and he'd philosophize to me. Chapman had been there all afternoon. I was sitting across the desk working, not paying too much attention to what they were saying. But after Chapman left, and 4 o'clock came along John leaned back and said, 'Paul, that man Chapman has got a good education hasn't he?' And I said, 'Yeah, John, I guess he has.' Then he said, 'That's the only thing he's got that I'd want.' He and Chapman didn't get along; they tangled over this grazing business all the time.

"John Kerr was criticized. I think all of those old timers were criticized later on for not doing more to reduce the numbers of stock, but they were handicapped. Nobody had the knowledge of what the capacity was. They actually did a tremendous job of getting any kind of compliance and they made a lot of friends among the stockmen. There was a lot of cooperation in those days. In Arizona, the attitude of the sheepgrowers is mighty good now."

Roberts attributed much of the cooperation between the sheepmen and the Forest Service in Arizona to the influence of Harry Emsbach, the first paid secretary of the Arizona Woolgrowers, who went to work for the organization in 1923.

"He was instrumental in dividing up the range," Roberts said. "He was always cooperative in working with the Forest Service. There isn't any doubt that he had a tremendous influence on the attitude of the Arizona Woolgrowers Association. Of course, in those days we had almost a million sheep. Now we have a hundred thousand or something like that."

|

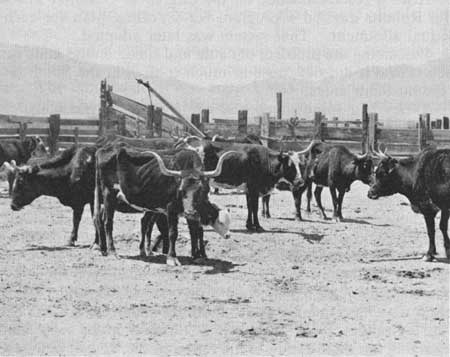

| Longhorn cattle were a familiar sight in the Southwest in the early 1900's. |

Regulation No. 64 in the first Use Book (1906) provided that "persons wishing to drive stock across any part of a Forest Reserve must make application to the Supervisor, either by letter or on regular grazing application form" and must have a permit from the Supervisor before entering the reserve.

Old time cowmen resented or ignored the regulation, and provided problems of trespass for the Rangers. The Gila Monster, the District publication issued from time to time by the people of the Gila National Forest, related this story of a trespass:

". . . An old-time cowman was trailing a bunch of four or five hundred head of cattle through a recently established Forest Reserve. On being asked for his crossing permit, he significantly tapped the six-shooter on his hip and said, 'Here is my crossing permit.'"

The Gila Monster for March, 1920, pointed out that "Twelve or fifteen years ago the members of the Forest Service were facing a united opposition to the entire Forest Service policy. Forest Officers knew at the time that the policy was sound; that they were engaged in a great public service which would benefit not only the present generation but future generations as well. With this knowledge back of them, the incentive to see it through in the face of all opposition and abuse was instilled into every member of the Service. . . .

"The Service policy is a recognized fact and has the support of practically all of the western people. The old-time spirit is still there, but is dormant because of the lack of opposition."

Sheep crossing cattle ranges was always a hot issue. In 1922 it was decided to establish a sheep driveway from the Salt River Valley to the White Mountains in Arizona. The driveway would have to cross cattle range. The cowmen came to the party with guns. The sheepmen did not show up. The driveway was not established.

Henry L. Benham, who started his career on the Black Mesa Forest (later divided among other National Forests) remembers no real range war on his District, but recalled that "sheepmen and cattlemen were pretty mad at each other."

Benham said that sometimes sheep from outside the Forest would be slipped in to get water. "They would slip in to Garland Lake from out north of the Forest, if we weren't watching. Or sheep would come in on another sheep rancher's territory and get water from their stock tanks or water holes.

"Cowman out north—I won't mention any names—I remember he shot and killed a sheepherder. He kept threatening and warning the sheepherder away from the water hole. He went down to the water hole and there was the sheepherder, and the sheepherder took a shot at him. He had his rifle and he fired back and killed the herder."

In contrast to grazing problems with non-cooperative ranchers, Gilbert Sykes, of Tucson, who was a Ranger on the Nogales District from 1952 to 1962, discussed harmonious conditions that existed there.

"That strip from Sasabe to Douglas, right parallel with the border and maybe not going over 30 to 35 miles north, the high rainfall comes in the summer months, just when you need it," Sykes said. "About 60 percent of the rainfall in the summer time in that strip, and about 40 percent in the winter. So we get a big growth during the growing season because of the extra moisture. There is lots of cover except in a few little isolated areas. There is a remarkably small amount of erosion. We have managed to keep the grazing load down to about where it be longs, by and large. While I was down there, and I think the boys that followed me have done the same—I had excellent cooperation from the stockmen. I've had several of the cattlemen time and time again come around and say, 'Hey, you know this season looks kind of tough. I took a hundred off the other day. To heck with it, I'm gonna lighten up.' They'd voluntarily do that. They played ball with us fine. You get that sort of cooperation, you don't have to go after too many range transects or anything else if they are willing to realize their responsibilities and try to stock pretty much accordingly."

Jesse Bushnell, who had been a Ranger at Munds Park and Sedona, was transferred in 1928 to Mesa, about the time the sheep were starting to come down the Heber-Reno Trail for the winter.

Supervisor Theodore Swift assigned Bushnell to "get up there and watch that trail. We had 75 trespasses in there last year, between Long Valley and Sugarloaf."

"I got up there," Bushnell said, "and the first band of sheep to come down was one of Scott's, and I helped. Those sheep had come all the way from Tonto Creek to Sycamore Creek at Round Valley. That was about a 5- or 6-day drive, and no water—no water. The sheep were heavy with lambs and they were almost famished for water. They'd come in there to Sycamore Creek and filled up with water. The trail was laid out so that when they crossed Sycamore they had to climb right up Herder Mountain where they'd been trespassin' the year before. When they'd watered at Sycamore just below Round Valley, they'd cut down to Sugarloaf on the east side of Herder Mountain, and it made the drive a day shorter and they didn't have to climb that high mountain. The trail come down like this, and then climbed the mountain and made this big elbow up there, right up over the mountain. So I told the rest of the sheepmen, 'Don't you pay any attention to the trail in there. Just go on the east side of Herder Mountain. Don't try to climb it after your sheep have been without water for almost a week.'

"So when I went to town I told Supervisor Swift, 'That's a dirty shame to try to force them sheep to climb Herder Mountain after they've been so long without water, and heavy with lamb.' 'Well,' he says, 'You try to get the sheepmen and cattlemen together and get 'em to widen the trail.' So I did. And there was no objection to it at all. By George, they agreed to it, and there they'd been fightin' each other for years, gettin' out there with guns, and everything like that. The cattlemen agreed to have the trail widened out, and they widened it out, and there never was any more trespassing. Now, sheepmen lost 300 sheep from Tonto Creek to Sugarloaf that fall, just died along the trail. We went over the trail and pulled the dead sheep up in a pile and set fire to them and burned 'em up. So next fall Mr. Swift gave me an allotment to build a tank up there at Round Valley, and we built the tank. So that put water in there for the sheep."

When, early in his career as Chief Forester, Gifford Pinchot visited Arizona he was particularly disturbed at the overgrazing of sheep and the damage this did to the Forests. In his book, Breaking New Ground, Pinchot reported that "not only do sheep eat young seedlings, as I proved to my full satisfaction, but their innumerable hoofs also break and trample seedlings into the ground. John Muir called them hoofed locusts, and he was right."

Soon after the Forests were created there was a movement to exclude all sheep. As Ed Miller recalls, "it required several years of hard work by men like Bert Potter and Lee Kneipp from Washington, and a lot of work on the part of the local Forest men to convince the Forester and the Secretary's office that sheep, as well as cattle, could be grazed within the ponderosa pine belt with proper handling."

When Alva A. Simpson was transferred to Region 3 in 1937 he became Chief of Range Management after a short period in Personnel Management. "I think I sensed a change in the attitude of stockmen commencing about 1930, possibly a few years before that, right after World War I," Simpson said in discussing conditions in the 30's. "Here in Region 3, I think there was very little change because the cattle industry in particular was based on yearlong grazing. It was based on numbers, and the use of browse to a great extent rather than grasses. Any interference in the way of regulation was not appreciated by the vast majority of stockmen. It was almost impossible to correct the condition because of the terrain and the type of country in which the cattle were grazing or were using."

Simpson said that as Chief of Range Management he stiffened up on trespass. "I decided that I would do the same down here in Region 3 that I had done in Region 1. If a person trespassed, he had to pay the penalty. And that penalty was going to be a pretty stiff cut on his preference. That commenced to stop the trespass pretty fast. We encouraged roundups, as far as we could finance them, and we commenced picking up this trespass which had been a problem in the Region for thirty or forty years—and gradually we commenced getting control. Now, of course, the big thing that has happened, to my mind, to conservation of the range resources and conservation as a whole, is the changed attitude of the public in looking at conservation as a national necessity, and the changed attitude of the press, of the recreation people and things of that sort."

He said he thinks the new generation, many of whom are graduates of agricultural colleges, "have been exposed to conservation practice and conservation knowledge, and have changed their ideas."

"I think you'll find not only better cattle, but better-conditioned cattle, few losses, and bigger calf crops today than you did 15 or 20 years ago," he said.

Simpson said he believed that there is a change in the attitude of stockmen themselves. "After a long period of time, they have come to the conclusion that there's more money to be made in having a productive range than there ever was in running a bunch of low-bred cattle, in scare-crow condition, just in order to get numbers."

In the 1920's, range surveys were taking on new or added importance as a means of developing long-term range management planning.

W. G. Koogler was for several years chief of party for range reconnaissance and part of the program was training Rangers and staff men.

"This first large scale program of Ranger training was followed by the influx of a steadily increasing number of technically trained men from the colleges," Koogler wrote in a report on range reconnaissance.

"Throughout the 1930s, increasing amounts of money became available to employ technicians for carrying on the CCC program, and this large influx of technicians along with the added force and emphasis given to conservation under the various emergency programs of the Roosevelt administration ushered in the beginning of a new era in range administration. By the start of World War II, most of the range staff jobs and a high percentage of the Region 3 Ranger Districts were manned by technicians. Keeping pace with the changes in personnel was the change-over from horseback to automobile travel."

Roger Morris worked as range examiner in the 1920's and described how the survey operated: "We were doing horseback surveys and we would just travel through the country and make notes on forage conditions, kinds of vegetation, herbage, topography and anything else that would be pertinent. We entered our data on maps. Then in winter we would go into the Regional Office in Albuquerque and work up our data and work up allotment management plans for the Ranger Districts in cooperation with the local men."

Morris remembered that when he was working up carrying capacity figures on a couple of sheep allotments on the Tusayan, the allotments were higher than the stocking that was actually on them at the time—a rather unusual situation. "The fellow in charge . . . his stocking figures were under my capacities," Morris said. "I happened to be up at his headquarters, up toward Grand Canyon, on the flats there, and I saw him one day and he said, 'Hell, the trouble with most of these cowboys around here, they don't know range. They don't know what a range is.'"

C. A. (Heinie) Merker believed the range policies of the Forest Service had improved tremendously.

"There was a time," he said, "when both our policies and our approach to range management were pretty sorry. The big improvement came when the biologists, let me put it that way, took over from the mathematicians. If you recall the old range reconnaissance system, I don't know how the formula went—multiply acreage by density by palatability, divided by forage-acre requirements, whatever the formula was. There was a time when the forestry people took that as Bible, you know. That was it. You stuck to that figure regardless of what the country looked like. Then they began to realize that it was less important to determine what the carrying capacity of the range was than the potential capacity, if it were given reasonable range management. That's when the big improvement started."

Merker cited as an example the area along the road from Grand Canyon to Cameron, along the Rim.

"In the early twenties I went through there," he said, "and the Grand Canyon Cattle Company was running cattle in there, and literally, it looked as if a fire had gone through there—wasn't a blade of grass, wasn't an oak leaf in reach of a cow, not one. It was just as though you had gone through with a blow torch and burned every leaf off of every tree, every oak tree in reach of a cow. Well, it doesn't look that way now. The range mostly is in good shape."

Roger Morris recalls that the first palatability figures that were used "we got more or less out of thin air."

"Those early figures proved to be very high as far as palatability was concerned," he said.

The figures were refined by trial and error, but the weakness was that in most cases stocking was not reduced to the extent the figures said they should be.

Morris said that while he was on the Tusayan National Forest he worked over old range surveys and made new ones and reworked the management plan set up for the Forest.

"We were never able to get the stocking down to the figures it looked like we ought to," Morris said. "It just wasn't administratively feasible at the time. I worked on some of that stuff on the Verde District. Well, when the Supervisor saw my figures for that, he almost turned pale. He was always pretty pale anyway. He said, 'My God, I know we can't. That's what we ought to do if we could do it, but we can't do that. It will be a long while before we ever get down to those figures.'"

When Fred Miller was working on the Carson Forest he walked as much as 50 miles a day when he was making a management plan. His widow, Mrs. Louise Miller, of Taos, recalls that Fred was away from home on one trip for about a month and that for most of the month his diet consisted of canned cherries and crackers. He had found a store that for some reason or other was out of everything but canned cherries and crackers.

"I met him at the Long John Dunne bridge over the Rio Grande," Mrs. Miller said, "and I had prepared fried chicken and all the trimmings. I never in my life saw a man so hungry or wolf so much food as Fred did that day."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap9.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008