|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER XIII

From Horses to Horseless Carriages

In the early days of the Forest Service horses were the only means of transportation in the Forest and each Ranger usually owned two or three horses. Even though he received only $75 or $90 a month, the Ranger was expected to buy and maintain his own horses and equipment. In fact, the first Use Book in 1906 noted that "Each Supervisor (and Ranger) is required to keep at his own expense, one or more horses, to be used under saddle or to vehicle, for his transportation in the Reserve."

The Datil National Forest also owned a team of horses which were stabled at Magdalena. Blueberry, a large roan, was an excellent saddle horse. Strawberry, also a roan, was a powerful bucker when the mood was on him. When the two horses were first acquired by the Datil office they were so wild it took three or four men to hitch them up to the light buggy inside the stable before the doors were opened. When the doors were opened, the horses made a wild dash for the open air, with the light buggy sailing over the ground. The team developed a bad habit of balking in the morning when they were supposed to be ready for a trip, which resulted in rather low mileage for the day.

Typical mileages for horseback or buggy trips were, from Magdalena: to Rosedale, 35 miles, eight hours; to Durfee Wells, 21 miles, five hours; to Tularosa Ranger Station, 85 miles, 2-1/2 days; to Hood Ranger Station, 115 miles, 3-1/2 days.

|

| Forest Service truck stuck in mire along Grand Canyon trail, Kaibab National Forest, 1920. |

When Morton M. Cheney, as a tenderfoot young lawyer out of the East, joined the Forest Service in 1913, one of his earliest assignments was to attend the 1913 fall meeting of Rangers at Willow Creek in the Datil Forest. One of his most graphic memories of that Ranger meeting was the arrival of the Rangers from the Apache National Forest.

"One of the prettiest things I ever saw was when we were already in camp," Cheney said. "The Apache Rangers came in, the entire Apache Forest, including the cook. They made the two-day ride from Springerville to Willow Creek. As you drop into Willow Creek, you drop off the first ridge and the switch-back down into the flat—and that group of Forest Officers, in uniform, with John D. Guthrie on a big black switchbacking down into camp, it was a beautiful sight."

Fred Miller used to enjoy talking about riding horseback to Los Pinos to go fishing. "I had one interesting experience there," he related. "I was there by myself and there was a little one-room overnight cabin. The front door step was about that high, and the back of the cabin was right up into the slope of the hill. I had a great big horse. He weighed about 1200 pounds, a big stout animal. I went down to get some water from the spring, and when I got back, here was my horse inside the cabin! I couldn't get him out because the door wasn't high enough—only about five feet high, and when the horse stood up, his head was higher than the door. I just couldn't get him out, and I didn't know what the devil to do. Then I remembered he was an oat hound, so I put some oats in a box, and when he put his head down to eat, I finally got him out. But it took me half an hour to get that horse out of there."

Edward Ancona, another tenderfoot forester out of the east in 1913, was assigned to the Coconino. "I remember getting on a horse that first day in Flagstaff," Ancona recalled. "I had rented a horse, and the Ranger had his horse, of course, and he said, 'We're going out to a point east of here—we have some sheep to look over.' I came out of the livery stable, and I didn't know how to steer the darned beast. So I sat on top with a pair of reins and used two of them. Well, he didn't know where he wanted to go, and neither was I quite sure where I wanted to go. We ended up crossing the street. The horse went up on the sidewalk and mounted part-way up the stairs of the Opera House before I got him turned around and back into the street. In the meantime, the Ranger had jogged off down the street in a typical jog-trot. I think he was pretty disgusted. I trailed him all the way out, some 12 or 14 miles, and 12 or 14 miles back, and I was 'skunned' from here to there! That was my first horseback ride. I learned though after that, because all of my work was on horses. You just had to adapt yourself to it, or you were sunk."

Later on (in 1916) Ancona was assigned to Taos. There he said, "we had to have driving teams, a team of horses that could both ride, pack and drive. I had two teams toward the end of the job because we went enormous distances there. We'd drive clear from Taos out to Dulce and the Jicarilla country. We'd drive to Tres Piedras and all that country, clear over to Canjilon. That was big country and the roads were very primitive, lot of them in deep sand. So you had to have horses that could drive, pack or ride, because we'd go as far as we could driving, then we'd leave this mountain wagon and put on our saddle and pack outfit and go on."

Roads in the Forests of the Southwest were almost non-existent in pre-World War I days. Outside the Forests they were nothing to brag about. New Mexico was building state roads with convict labor in those days, and in 1917 boasted that the Camino Real "is an improved road from end to end"—Santa Fe to El Paso—and that a 5-year plan was being developed for an elaborate system of state highways, aggregating 3,540 miles.

Arizona had the advantage of a number of military roads that crossed the state, but mostly the roads were "natural roads" that could be traveled only in dry weather. In the northern part of Arizona this offered some hazards.

Early in the century, the Bureau of Reclamation had undertaken construction of Roosevelt Dam. To make transportation of materials to the damsite possible, the government constructed 60 miles of road from Mesa to Roosevelt.

Describing a trip he made to the dam while it was under construction in June, 1908, A. O. Waha called the road "certainly the best in the Southwest at that time."

"Many freighters with their 8 to 16 horse or mule teams were on the road," Waha related in reminiscences some years ago. "My trip was made in a Concord stage (leather springs) which was drawn by four horses. Horses were changed four times during the trip so twenty horses were required for the trip which was made in a day. For the first 18 miles the road traversed the level desert country where the giant cacti grow; then through foothills country for about 30 miles and then into the mountain country. The road has splendid grades and a good surface. Fish Creek hill was the real scenic spot along the road. Here the road was made by blasting some solid rock walls. Approaching the highest turn on this hill, the stage driver hit up his horses taking it on a high gallop. While there were passengers inside of the stage, I sat on the high seat alongside the driver. It was surely a real thrill when we were rounding this high point on the curve and I could look down over the sheer cliff which was about 500 feet high."

In May, 1909, a few months after John D. Guthrie had been appointed Supervisor of the Apache National Forest, he was directed to locate a feasible route for a road over the Blue Range and White Mountains of eastern Arizona. At Clifton, Guthrie was joined by District Engineer Jones of the Regional Office in Albuquerque, and by David Rudd, an Apache Forest Ranger.

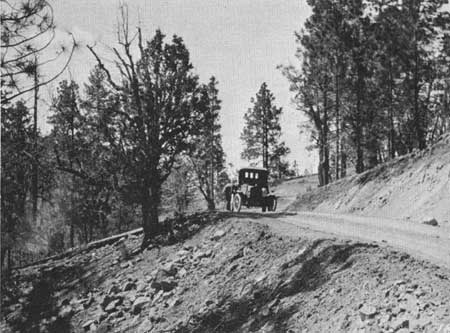

|

| Customary locomotion up Luna Hill, Alpine (Ariz.) Reserve (N.M.) road, June 1920. |

Seventeen years later, Guthrie told the story of that trip in a paper presented at the dedication of the Coronado Trail Road. Here is an excerpt from that unusual story:

Jones knew nothing of the country, having come into Clifton by train; my knowledge was limited to what I had been able to see from the bottom of the Canyon of the Blue, which wasn't much to worry about. Only David Rudd was familiar with the region through which we were to go. He had accidentally shot himself through the side about a year previously and not having recovered, it was decided not to take a pack outfit on this trip, but to stop at what ranches or cow camps there might be encountered; we encountered none!

From all possible sources of information about the country and from what maps were then available (and these were few and poor), the most likely route seemed to be to follow the old Mitchell Road out of Metcalf and then keep on the divide between Blue River and Eagle Creek, to the top of the Blue Range, to go around the head of Black River and the Campbell Blue, and on into Springerville. How to get to the top of the Blue Range, that was to be a problem.

That became the route later, but when we started we didn't know just where we'd land, nor where we'd stop for the nights. David could not tell for he did not know whether we'd go up Eagle Creek, up the Blue, or up the divide.

Anyway, we started out, three men, three horses, three saddles, and one canteen and three small lunches. The first night out from Metcalf I well recall. It was somewhere on the southside of Grey's Peak. There was a spring with watercress in it; there were pine trees and pine needles, and only Arizona's blue sky overhead for a cover.

No bedding, no chuck, except the dried remains of a lunch we had had put up at Metcalf. We sure slept out. Somehow we put in the night. I wonder if the new road goes by that spot?* The Spanish captains of Coronado's caravan may have camped in that spot on their way from Mexico to Zuni in May 1540. Who knows?

*It does.

The captains may have known as little about the country as we did, but they did have 600 pack animals and provisions. Our caravan of 1909, 369 years later, certainly was traveling lighter. Their record speaks of big pines, watercress and fish in the streams, and wild game. That first camp of ours was Spartan in its simplicity. We just stopped, threw off our saddles, hobbled the horses, built a fire (merely for social purposes), and somehow the night wore way.

The next morning Dave Rudd did something I never saw done before. He had an old-style army canteen, the kind with the laced canvas cover. Dave had some ground coffee along, but there was no pot, no cups, no cooking outfit. There wasn't even an old tin can left by some former camper.

Coronado must have left a clean camp and a dead fire. May all his followers over this trail do likewise. Dave's Ranger ingenuity came to the front. He ripped off the cover of the canteen, filled it with water, set it upright between two rocks, and built a small fire around it. When boiling well, he lifted it from the fire, poured in a lot of coffee—and, after steeping and cooling, we took turns at the breakfast coffee urn. The coffee was strong—muy fuerte, as the local saying is, but it was our life-saver. That was our breakfast and coffee never tasted more wonderful. Perhaps Coronado's men quenched their thirst in a heavy Spanish wine, but it could not have tasted better than our canteen coffee that May morning in 1909.

I don't think the engineer cared for the camp nor the coffee particularly, especially since he was wearing on this trip a stiff white collar.

We were simply looking over the country to see if a road were feasible, on not too heavy a grade, and at not too prohibitive a cost, from the copper towns of the south to the cool, green forests to the north with the fish, water cress, pine trees, and wildlife of Coronado's day.

We followed as best we could the divide between the Blue and Eagle drainages, through Pine Flat, circling Grey's Peak and Rose Peak, and struck the rim of the Blue Range, climbing it over a trail that went nowhere but up.

That was the third day out from Clifton. Dave supplied the knowledge of the country that could not be seen; the engineer (in a collar now not quite so white) took many "sights" with his level and made many notes, and we climbed to Hannagan Meadow and rested there the third night. The snowdrifts were plentiful and deep.

The engineer still wore his stiff collar, now past all semblance of its former self. There was neither fence nor cabin at Hannagan Meadow. Two deer came out in the Meadow early next morning to feed. A grouse whirred away from the spruce tree under which we slept. There was white frost on the aspen poles around the spring when I went down for a drink. Across our trail down to Black River that morning stalked a flock of wild turkey.

That day we rode into Springerville from Hannagan Meadow, a right nice little ride, via the Slaughter Ranch, Big Lake, Pat Knoll, and Water Canyon, with big appetites and tired horses, and one dark-brown, still a collar, on the neck of the engineer.

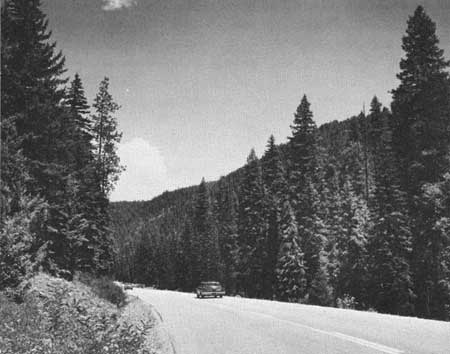

|

| Road between Alpine, Arizona, and Luna, New Mexico, May 1924. |

The conclusion at that time—and that was in 1909—was that such a road could be built, with a fairly good grade, but that it would be expensive. Somewhere in the Government files are Engineer Jones's report and maps covering that reconnaissance for a road from Clifton in Greenlee County to Springerville in Apache County. The next year (1910), another government engineer (Howard B. Waha) made another reconnaissance, but his route ran up Eagle Creek, through the Indian Reservation, and around the west end of the Blue Range.

This is now 1926. It has taken 17 years to build that road. Governments move slowly and cautiously. That looking over the country for a road in May, 1909, was the very beginning of the Clifton-Springerville Road. Coronado went over it, but he was looking for gold and treasure, not roads.

His historian, Castenada, did set down what are destined to become treasures of the region, perhaps as valuable as the mythical gold Coronado sought—the tall pines, the fish, the watercress, the wild flowers, and the wild game.

Now people will again come up over this route from the south, as Coronado and his captains came, seeking something. I wonder if the Spaniard put out his campfires, if he left camps clean. With 600 pack animals and 1,000 men he must have had many camp fires gleaming in the pines along the route from the "Red House" to Zuni. Being a soldier, I suspect he had order in his camps; I suspect he left his campfires safe; he must have left some fish, some game, some watercress, and the oak, pine and spruce trees, for they are still to be found along his old trail.

By 1917, the Forest Service was ready to start the actual survey of the Clifton-Springerville road, and Fred H. Miller was assigned to the task. World War I interrupted, and Miller along with many other Rangers and Forest officers, enlisted.

From its earliest years, the Forest Service had made allotments for roads and trails, but for the most part these were small ($42,000 for New Mexico in 1916)—and as with the Coronado Trail, accomplishments in road building were slow in realization.

After the war, the Forest Service again resumed plans for road building or truck trails as they were called. Ed Miller (not to be confused with Fred Miller) recalled that he arrived in Flagstaff from assignment in Prescott in 1919—"at about the beginning of the rainy season."

"Ray Marsh was Forest Supervisor," Miller said. "He had succeeded John D. Guthrie. He wanted to show me a part of the south end of the Forest, but was afraid we couldn't make it by car and he didn't have time to start out with a pack outfit, so we hired a man who was running a country taxi business there at Flagstaff. We started for Winslow and bogged down on the way, got there after dark. There were no built roads. The only graded road on the Coconino at that time was a strip that Howard Waha had built between Flagstaff and Williams. It was, as I recall, about 14 feet wide; part of it was made of cinders. There was another little strip of road from Long Valley east across Blue Ridge. It has been constructed but not surfaced.

"Anyhow, when you started out on a trip in a rainy season you never knew how many miles you would make. Ray and the driver and I stayed all night in Winslow and started for the Bly Ranger Station, southwest of Winslow about 20 miles. We bogged down at about the half-way point, worked three or four hours in getting out of the mud. We cut greasewood and branches from junipers and found a few stray rocks. We got to the Bly Ranger Station and Fred Croxen, who was there at the time, said it was impossible to get on toward Long Valley so Ray Marsh called up Bill Brown and had him come over on horseback and we chatted there for an hour or two. Made it back into Winslow that night, and made it back to Flagstaff without bogging any more.

"Jim Mullen was out in 1923, made a roads inspection trip. The clouds looked like a heavy rain was coming on so we left the Long Valley Ranger Station somewhere around 3 o'clock that afternoon. We bogged down—had on chains of course—bogged down about the east end of Blue Ridge. One chain was broken almost beyond repair. We got down pretty close to the east boundary of the Forest. We had figured on going on into Winslow, even though darkness came on and our lights shorted. It was pouring down rain. Jim and I pulled out at the side of the road, built a fire, cooked our supper, bedded down in the old Dodge truck. We were thankful that we had a truckbed long enough to accommodate our beds. Along in the middle of the night we heard a big car pass us, slopping through the mud. We got up in the morning and the rain had stopped. We cooked our breakfast and leisurely packed up and headed for Winslow. In a big flat pretty close to where Ray Marsh and the taxi driver and I had bogged down in 1919, we found a big Cadillac with Boyce Thompson and his driver in a rented car bogged down hopelessly. Thompson was the man who established the Boyce Thompson Arboretum at Superior, Arizona. He said, 'Have you boys any spare gas?' We said, 'Yes,' and he said, 'Thank God for the Forest Rangers!' We put a 5-gallon can of gas in the old Cad, but there wasn't enough manpower available to move it an inch. Mr. Thompson asked us if we would have the owner of the White Garage in Winslow send a car out with plenty of planks and plenty of gas. They told us in Winslow that they would go right out, which they did. Jim and I found that we couldn't make the road north of the Santa Fe Railroad back to Flagstaff without danger of bogging, so we took a route south of the tracks, in places as much as three or four miles south. We came to the first big arroyo west of Winslow, probably four or five miles out, and it was in flood stage. It was still raining—rather raining again. We watched a lot of those people try to go across. Several of them bogged down. Jim and I finally decided instead of hitting the water hard, we would creep through, which we did, with the old Dodge. It was impossible to do anything for the people who were bogged down. It was a case of more help than we could give so we made it back into Flagstaff that night."

|

| Coronado Trail, Apache National Forest, is one of the most scenic in Arizona. |

Discussing the building of the truck trails on the Coconino, Miller said that one of the all-time foremen was John McMinnimum. His wife was cook. "We wanted to build a fire trail across East Clear Creek Canyon," Miller related. "We worked Mac down there two winters with a bunch of burros and five or six men. They camped down on the water most of the time at Clear Creek. Mac was one foreman in a thousand. He had learned blacksmithing when he was a boy. He had an eye like an eagle. You could rough out a line with an Abney level, and he'd do the rest. I don't suppose any foreman ever built more road in two winters than Old Mac did, with less supervision, because he didn't need it. The Ranger would go down occasionally to see what supplies were needed. But Old Mac would work all winter, maybe lay off one or two days. He built trails, truck trails and fences for us until the CCC boys came along. Then he went on as road foreman for the CCC. We always figured that people like the McMinnimums made America. There were many fine people in the rural areas in those days—in the Zuni mountains, on the Datil, on the Prescott, and the Coconino."

Ask any Ranger about problems of the early twenties, and the reply will be transportation. When he went to the Sitgreaves Forest in July, 1922, Paul Roberts found that there were no good roads, away from the main roads, on the Forest.

"The program of truck trails was starting," Roberts said. "We cleaned out the old Rim Road, the Apache-Camp Verde military road along the Rim, as far as the Coconino Forest. The Coconino cleared it out from there on. Of course, all the canyons headed up close to the Rim, so the road headed the canyons. Once we got that cleared out we built truck trails. There wasn't much building. We cut truck trails and cleaned them out down between the canyons so we could get in to fires with men and equipment a good deal faster than we could in the old days with pack horses.

"One of our early experiments—somebody got the idea that we might put a truck equipped with tools, fire-fighting equipment, between Wildcat Canyon and Chevelon Canyon. So we rented a truck took it up around the Rim and down between the canyons, and placed it where we could get to it as quick as we could get over there on saddle horses.

"The first fire we had was a lightning strike, and it was right near the truck. It burned the whole outfit up before we could try out how effective our experiment was. It took us about a year to get approval to pay the fellow for the truck.

"Then the next flurry—we decided to build a road, a crossing on Wildcat Canyon. Aldo Leopold was Chief of Operation, and I was just a young Supervisor and inexperienced. Leonard Lessel (Assistant Supervisor) had more experience than I had, so I took him into the conference. When we asked for an allotment to build a road across Wildcat, Aldo was so dumfounded he said, 'Well, that is a crazy idea.' Since I was a young Supervisor and inexperienced, I wouldn't be reprimanded for such an idea, but it was totally impossible.

"But the next year, Evan Kelly, who was an engineer and a road builder, came along on an inspection, and he said, 'Paul, why don't you build a road across Wildcat Canyon—and across Chevelon, too, so you can get across there?' We built the road across Wildcat Canyon while I was there, and soon after I left they built a crossing on Chevelon Canyon.

"I remember particularly about a road up to the lookout on Lake Mountain. I checked up with Lessel and he said we had plenty of money to finish that road. So I went ahead and built the road, and when I got through I found out that I was $800 short. So I wrote in—Jim Mullin was handling allotments then—so I wrote in to Jim and I said, 'We're $800 short; we need to increase our allotment.' And Jim wrote back a little note and said, 'You can overdraw on the checkbook, but you can't overdraw at the bank.'

"I had a well-experienced clerk there and he said, 'The Government always pays its bills; let's just wait and see what they do.' So we never wrote in to the Regional Office about that any more. We just sat there, and in about a couple of months, along came an increase of allotment in the amount of $800.

"There were no paved roads in Arizona, except a few miles out of Phoenix at that time. As I remember, along in '30 or '31 they built a mile of experimental oiled road between Holbrook and Gallup. That was the first oiled road that we had. Of course, as I have said, transportation was slow. Right after the War, while I was still in Albuquerque, the office asked me to take a Ford sedan, which was a transfer from the War Department, out to the Tusayan from Albuquerque. Tusayan was having some fire difficulties and they wanted to speed up their transportation.

"I thought that would be a good trip for my wife to go along, so we left Albuquerque that morning about 10 o'clock and got to Thoreau that night, late that night. But before we got into Thoreau, we'd gone through an arroyo and twisted the hose connection off the radiator and had to walk in about a mile. They were having an oil boom at Thoreau at that time and the oil men were having a poker game in the hotel and one of them said as soon as he'd lost his stack he'd go out and pull me in. He won a little money before he lost it, but he finally lost what he had, and we went out to get the car and bring it in. We made the necessary repairs that night and started out at sun-up the next morning and by driving real fast and hard we got into Holbrook that night about 9 o'clock. We left there early the next morning and got into Williams after dark that night. That was three days from Albuquerque in a Model T Ford. After that we took a vacation and went up to Grand Canyon. That gives you some idea of the speed of transportation in those times.

"Then, in the fall of 1929, or '30, the first emergency money that we got was still in the Hoover administration. They asked us how soon we could start crews to work if we had the money. I told them we could start the next morning. I believe we got an allotment of about $3,000. Right at that time, or about that time, we had started the road crossing, at what we called the Mormon Crossing, on the Chevelon District, down near the old Marquette Ranger Station. All the drilling for use of powder was done by hand. Well, we got a jackhammer. It was the first one on the Forest. Bill Baldwin had laid out the road so we'd have the easiest going with the ordinary methods of construction, and I'd approved the location. About two or three weeks later I went back out there to see how they were getting along. In the meantime, Bill had gotten the jackhammer and he'd completely changed the location of the road. He was going around a rock ledge which really was a better location. They were really usin' that jack hammer to blow out that road and get around there. They thought that was really something. Those tractors and that jack hammer were the first pieces of real equipment that went out on the Sitgreaves."

Today there are Wildernesses and Primitive Areas in the Forests where vehicles are prohibited, but otherwise Rangers can cover their patrols with pick-ups and 4-wheel drive vehicles. But the old-time Ranger still loves his horse as the way to get around the country. As Ranger Henry Woodrow of the McKenna Park District once said, "I expect to keep riding them as long as I am able to—up until I am a hundred years old anyway."

Stanley Wilson, a technically trained forester, graduate of the Yale Forestry School, spent his entire career in Ranger and Supervisor positions, and he summed up the feelings of a lot of old time Rangers about working their Districts on horseback:

"As a retiree who knows nothing about the facts, I just want to make an observation or two. In my day, of course, we rode horseback. We were encouraged to make trips where we had nothing in particular to do except to see the country. I never made a trip of that sort but what I came up with something I ought to know. I remember the trip I made on the Catalinas. I just went into an area to see the country. I found goats in trespass. I didn't know there were any goats in the Catalinas. I found a fence that had been built. Basically we were doing this to get acquainted with our District. We did know the nooks and corners, but as I say, we almost always found some good reason for being in that place that we couldn't think of. Now, of course, there are roads everywhere. We have roads to our lookout; we have roads everywhere . . . but I can't help thinking that men don't know their Districts as well, traveling in a car."

Wilson said that when he moved to Phoenix as a retiree, he ran into Hugh Cassidy at Springerville.

"Stan," Cassidy said, "when you move out here and get settled, come on up and take a week's trip with me."

"Well," Wilson said, "I'd love to, Hugh. I haven't forked a horse in 15 years."

"Who said anything about a horse?" Hugh asked. "We're going in a car."

"Go to the devil," Wilson said. "I don't want to ride with you."

And he added, he never went.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap13.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008