|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER XIV

CCC Days

Edward G. Miller was Supervisor of the Coconino National Forest in 1933 when the telegram arrived at his Flagstaff office advising him that some 500 to 600 CCC enrollees would be assigned to the Flagstaff area. Miller was advised to be prepared to take care of them.

Similar telegrams were being received by other Supervisors as the Federal government's emergency program to combat the Depression got underway. With about one-fourth of the population of the United States between 15 and 24 unemployed, and as many employed only part-time, the government was taking dramatic action to cope with the problem.

Chief of the Forest Service Robert Y. Stuart had estimated that 25,000 men would be put to work in the National Forests. Within a month he had been asked to increase the number to 250,000 as plans went ahead to enroll young men in the Civilian Conservation Corps. At its peak the number of camps increased to 1,500 and an enrollment of half a million.

In the Regional Office in Albuquerque, Hugh Calkins was Chief of the Operations Division and Stanley Wilson was assistant.

"I was rather amazed at how wonderfully Hugh Calkins found camp sites and places and work for all of the camps," Wilson recalled. "My own part of it was handling personnel."

The establishment of the CCC camps put a great drain on available supervisory forest personnel and new technical foresters had to be obtained and obtained quickly. Prior to that time when technical foresters were needed, it was customary to send word to the forestry schools for the names of people and resumes of their qualifications.

"We'd peruse the lists and look wise and pick the people we wanted," Wilson recounted. "Of course it didn't do us any real good."

Because he was not happy with the system, Wilson—shortly before the start of the CCC program made arrangements with 10 forestry schools for selection of candidates for employment.

"I don't want your histories of these men," Wilson told them. "They mean nothing to me. What I want to do is to be able to call upon you for so many men to be either camp superintendents or camp foremen—and here are the qualifications. I don't want their qualifications, because I want you to be willing to stand behind them.

"So when the CCC program broke, I sent for 80 men from the 10 forestry schools. Then there was a delay in the program, and for a day or two we didn't know whether we were going ahead or not. I was afraid to take the men, yet on the other hand if I cancelled the order for them I would be out of luck. So we sat tight, and fortunately the order came to go ahead. We got 80 men, and the heads of the forest schools did such a good job that actually we had no lemons in those 80 men. I think we had unquestionably the best group of technical foresters any Region got."

The various Forests were setting up camps to handle the influx of enrollees.

Edward Miller reported from Flagstaff that with Major P. L. Thomas from the regular Army, his lieutenant and a sergeant, "we looked over several possible camp sites and agreed to put one camp north of the city reservoir, out from Flagstaff where water could be obtained from the city power plant; one camp at Double Springs on the west side of Mormon Lake; one camp at Woods Springs on the Munds Park District."

"By the time the enrollees showed up," Miller said, "our boys had installed water mains, storage tanks, had made some clearings and were ready for the CCC camps to be established.

"We had some of the technical foremen, forestry graduates, start on timber-stand improvement work as soon as possible. We started some fencing work, some erosion control, like building little check-dams in some of the arroyos. Looking back, it seems to me that those spring developments were mighty important from the viewpoint of forest grazing permittees.

"We also started in on some recreation improvements. Recreation was just coming into its own on the Coconino. Oak Creek was a favorite spot, also Mormon Lake, and Lake Mary."

The level of Lake Mary was low in 1933, and a lot of water was being lost from holes and fractures along an old fault line in the limestone bottom of the lake. It was decided to try to plug the holes. The State Game Department provided truck loads of cans to save the fish before the repair program got under way. CCC boys seined for days getting out bass, crappie, and ring perch, which were then transported to other waters. Then crews of CCC boys with trucks and other equipment began the task of repairing the leaks in the lake bottom.

"I remember one crack that must have been 300 feet long and several feet wide." Miller said. "One of the big holes that had been filled with brush and clay in 1905 and '06 had opened up. We decided we would put in layers of limestone rock, carefully laid, then layers of clay. We found a sizeable clay bank, from which dump trucks were loaded by hand. Weeks were spent on this work. The clay was compacted as it was put in.

"By the time the camp was to move to winter quarters, the boys had filled all holes and all cracks that were visible in Lake Mary. That was one job where the CCC boys really accomplished something that meant a lot to a lot of people. Lake Mary is a favorite camp ground, a favorite fishing lake for a lot of people from Phoenix and other points in the desert as well as local people.

"Other recreation work included fireplaces, tables, water lines. One water line in Oak Creek was extended from the Upper Spring in Oak Creek Canyon down to Pine Flats campground. Other springs farther down were also developed.

"Incidentally, it is interesting to think back and realize the change in thinking. The most desirable places, like Pine Flats and Oak Creek Canyon, were laid out by Aldo Leopold and his helpers as summer home sites back in 1917, '18, or thereabouts. Fortunately, most of those summer home sites were never rented. But now I understand that people come from California, and other distant States, for a few days' camping in that beautiful canyon.

"Sedona was winter quarters for one CCC camp; another was placed on the upper part of the Beaver Creek Ranger Station site, and another on the upper end of the Clear Creek Ranger Station site. Those camps were located so that considerable recreation and range improvement work could be accomplished. Thousands of little check-dams were put in, camp sets were constructed up in Navajo Creek Canyon, stream bottoms were fenced, checkdams put in.

"Unfortunately, we had no guides for them and the engineer who gave advice had to go by rule of thumb. I just do not know how many of those checkdams were destined to last until the present time. We fenced some of the stream bottoms as we figured that by reseeding those stream bottoms and keeping cattle out, Old Mother Nature would revegetate and that possibly more permanent good would result than would be accomplished there by the construction of checkdams.

"A person would have to admit that a lot of those kids that came out as CCC workers were pretty poor help for a few months. Very few of them knew how to use tools. We didn't get too much use of them in firefighting. Even though the actual work accomplished amounted in real permanent values to only about a dollar and a half a day, those boys certainly received permanent benefits from their experiences at the CCC Camps. The foremen reported that they developed some fine Caterpillar tractor drivers, some good road-grader operators. Unfortunately, too much of the first equipment that was available was of poor quality; some of it was almost useless. But it served the purpose in a training program. I have no doubt that a lot of the CCC boys who learned to operate equipment filled important places overseas in the Second World War.

|

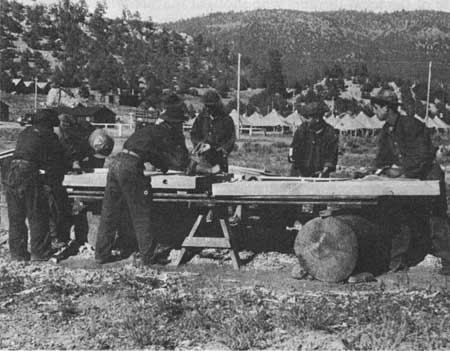

| The Civilian Conservation Corps, organized during the "Depression" days of the 1930's, accomplished many worthwhile projects on the Southwestern National Forests. |

"I can say that CCC camps alone did not and cannot meet the needs of some Forest-dependent communities. The local boys in communities like Camp Verde, Winslow, and Flagstaff, Northern New Mexico, need the work on roads, trails, firefighting. It seems to me that our local people cooled off a little after the CCC boys came in, because they felt that they and their boys would not be used on the various jobs that required temporary labor during the summer months. However, I think that the provision that allowed Forest officers to enroll some local enrollees, who were qualified to guide the boys from the big cities, had a tendency to cool off some of the local farmers who thought that we were doing them an injustice by bringing in outside boys to do the work that they had participated in over the years. Actually, when we found that so many CCC boys were afraid to use tools, we used local men when it was possible to get them."

With the availability of CCC boys to do the work, recreation sites got increased attention.

"We began to develop recreation areas all over the Region," Zane Smith, a Ranger on the Prescott and Cibola Forests during the late 30's and early 40's said. "There were over 400 recreation sites developed in about a ten or eleven year period. Some of those were quite small admittedly, just a toilet and maybe a dug garbage pit with a cover over it, one table and a fireplace. They went all the way from that sort of a set-up to a 50-or-60-family unit, comprised of table, fireplace, and essential facilities.

"Recreation use began to pick up along through the '30's, with the various alphabetical programs that were helping the country get its feet back on the ground and pull out of the depression. There was a five-and-a-half-day week, there were roads being built making it a little bit easier for people to get around and into the forests. Recreation began to command quite a spot of importance in Forest Service work."

One of the interesting little projects accomplished by the CCC was the construction of the Catwalk bridge in Whitewater Canyon near Glenwood. They made use of hangers and material that had held up a pipeline through the canyon during the early mining days.

Sam Servis was a Ranger in the Magdalena District during the later 1930's, and he recalled an old report in Socorro, written in longhand regarding the mining operation in Whitewater Canyon.

"They piped water some three miles down Whitewater Canyon to the Competence Mill site," Servis said. "To pipe this water, they laid an 18-inch pipeline. To maintain it, the miners got to walking the pipeline. They are the ones who called it the catwalk because of walking the pipeline. It was just suspended there in the canyon. They climbed up it and walked on up it.

"The water was piped down, generated electricity and ran the machinery at the mill. At one time they had so many people around there, they called it the town of Graham. The town flourished and they shipped out many thousands of dollars worth of ore. The first office of the old Gila River Forest Reserve was located there before it was moved to Silver City."

The mine and water line had ceased operation in 1914, but the stream was popular with hikers and fishermen and the bridge built by the CCC as a successor to the pipeline was also called the Catwalk, as it is today.

The CCC bridge rotted out in recent years and was replaced by a steel bridge, which had been moved from the Sitgreaves Forest.

Servis recalled that the Regions engineers who had first started out to design a new bridge for the meandering catwalk location finally gave up in disgust and despair "and threw all their papers and pencils out the window and told Bob Leonard (improvement foreman on the Gila) to go get his torch and a couple of helpers and put the bridge in. It was a good winter job and so old Bob and his helpers went up and put that bridge in—with just a torch and his own ability to make it fit. It was an extremely fine job. For a good many years that steel bridge will be there and handle lots and lots of people."

Walter Graves, who became Regional Chief of Operations in 1961, was one of the 1933 forestry graduates who had come to New Mexico for work in the CCC program.

"As a matter of fact," Graves said, "I was only one of two in my graduating class that were still at Iowa State for graduation to receive our diplomas. The rest of the class had already gone to CCC camps all over the country.

"I arrived in Santa Fe about the middle of June 1933, and at the same time a forester from Oregon arrived to be in the same camp. The Supervisor, Frank Andrews, was so busy getting CCC camps established that he was not available for the first two weeks that we were in Sante Fe. Each morning we would go to the office and receive word that the Supervisor was still out, and that we would not be assigned to a camp until he returned. So for two weeks this other man and I spent our days reporting to the office and finding out that the Supervisor would not be back, and then just waiting until such time as he did show up. After two weeks, Mr. Andrews finally came back into town and called the two of us in and told us that we would each be assigned to different camps. He assigned each of us to a camp by flipping a coin. The camp I was assigned to was the one at Hyde Park, about 10 or 15 miles out of Santa Fe. This was a tent camp and was composed mostly of boys from Southern Texas. We spent all that summer at the Hyde Park camp doing mostly erosion control work in the Hyde Park area, with a small side camp in Santa Fe Canyon doing some erosion control work there, as well as timber-stand improvement work."

In the fall a permanent camp with wooden barracks and all necessary facilities was built at the edge of Santa Fe. (During World War II this became a Japanese Detention Camp and later the site was sold and became the Casa Solano subdivision.)

Graves had assignments other than CCC camps for several years then in March '39 became a full-fledged District Ranger with headquarters in Coyote on the Carson National Forest.

"While at Coyote, we had a CCC camp just below the Ranger Station that was there until World War II was declared.

"The Ranger's house at Coyote was rather primitive. When we moved there, there was no electricity. We used gasoline lanterns and later Aladdin's lamps for light, and a kerosene operated refrigerator for refrigeration. There was no plaster on the interior walls of the house, just mud, but the year after arrival I was able to get the CCC crews to replaster the house.

"One of our major problems at Coyote was the distance we had to travel to do our shopping. There was one small store in Coyote. The selection was quite limited and about all we could get were canned goods and a few staples. We made a trip every two weeks to Santa Fe for all of our supplies. During the summer, of course, with fire season, I was not able to go with my wife when she went on her two-weeks shopping tour, so she had to go by herself. It was quite a sight to see her come home to the Ranger Station with two youngsters in the car, two weeks supply of groceries, 200 pounds of chicken feed, 10 gallons of kerosene for the refrigerator, and five or ten gallons of white gas for the lanterns. The car was so loaded it would hardly clear the wheels."

Commenting on the CCC operations, Graves said that "the Army had the responsibility of organizing the camp and handling all of the logistics, and the complete operation of the camp itself. The involved agencies, land management agencies, were assigned the boys in the morning, took them out on the job and were responsible for them until they returned to camp in the evening, at which time the Army took them over and of course was responsible for them until the following morning. The regular Army was the nucleus of the camp operations, with a number of reserve officers assigned, particularly in the later stages of the program. At the time the program was dropped, it was operated almost entirely by Reserve officers. Of course the program was stopped when World War II started. Had it not been for that, we undoubtedly would still have a CCC program, would have had it all through these years.

"We built many miles or roads, lots of range fences, range improvements of all kinds, erosion control, and while this Region did not concentrate on the construction of administrative improvements such as Ranger stations, a number of Regions did, and of course these buildings are still in use today.

"We had men in our camps out of Santa Fe who had doctors' degrees, and a number of men who were high school and college graduates. But they were not able to find work at all, and this program was aimed at providing work for those people who just could not get a job. Some of them came hungry—very hungry—men who had been out of work, with families to support, been out of work for months and months."

Norman Johnson, of Flagstaff, was a construction foreman on the Coronado Forest, and one of his CCC assignments was to build a combination guard and fire cabin at Cima Park.

"It was a complete installation, telephone lines, water system, a large cabin. In the building specifications, it called for two fireplaces to be built back to back. Every fireplace I had had anything to do with in those days either smoked or provided inadequate heat. You'd have to stand up to the fire, and if you were facing it, you're warm on that side and you're cold on the opposite side. I had no idea how to build a fireplace back to back and the plans didn't detail it enough to know. So I wrote the Government Printing Office and sure enough, they sent me the details that I needed to get the job done and it worked very satisfactorily—a double fireplace with one chimney.

"Another thing about the building—we had to cut the logs, skid them with a mule. As a matter of fact we had to pack everything in from Rustler Park, at the end of the road, to Cima Park. So everything had to come in by pack animals.

"The plans called for windows lying horizontally, like log cabins were in those days. Now, I'm rather a tall person, and the windows were either too low when I was standing up to see through or too high to see through if I was sitting down. I came up with the idea I wanted a window I could see out of. I took it upon myself to stand the windows up and down so I could see out.

"Fred Winn, (Supervisor of the Coronado and by then an old timer) came up on an inspection trip, accompanied by Mrs. Winn.

"I doubt very much whether Mr. Winn noticed this change. But certainly Mrs. Winn did—and I really heard about it! It was a log cabin that wasn't a log cabin."

Johnson stayed with the CCC program through the rest of its existence until it folded in 1942, working mainly with campground construction. Several summers were spent operating what might be termed side camps, which were camps away from the mother camp.

"I recall that it was rather an imposing task to be camp commander, educational advisor, the 'doctor,' the project superintendent, all in the camp, plus running the crew during the day," Johnson said.

"I can remember having side camps on top of the Huachuca Mountains and we would be there for weeks on end, because a person would have to walk off the top of the mountain and it wasn't worth walking off the mountain to go to the main camp. We furnished our own recreation in the form of hikes, horseshoe games. There wasn't any place level enough for a baseball diamond, but we'd have an area where we could play catch, so we were rather a complete camp."

As the CCC program was getting started, Ranger Zane Smith, who had just been transferred to Alamogordo, drove up to Albuquerque on a personal business matter one week-end, and visited Landis Arnold, who had just been put in charge of recreational programs for the Southwestern Region.

"Pink, who had shown a great deal of personal interest in this sort of thing, had scrounged around and managed to build a few old tables out of scrap lumber, and give some attention to the recent recreationists from Albuquerque, out in the Sandias. This caused him to be selected to head up this work. He was a real good administrator, but surveying and mapping was something beyond him; he was never able to grasp it. About the time I came to Albuquerque on this little private business trip, Pink was looking for somebody who could fit into his organization and head up the mapping side of it. I just happened to come into view and he knew me, knew that I could do that sort of work, so I was immediately tapped for that. I remember we had moved into an apartment in Alamogordo that was a second choice. We were told if we would occupy this temporarily, one of the better apartments would be available soon and we could have it. Well, the weekend that I came to Albuquerque my wife got the new apartment and moved into it. When things firmed up on my move to Albuquerque I had to move her out of it. We did a lot of moving in a short space of time.

"That was quite a move, to be attached to the Regional Office, for a youngster getting started. My working area suddenly became all of the National Forests in the States of New Mexico and Arizona. I was probably feeling pretty cocky over what I considered to be my good fortune. I took off with a lot of confidence and no knowledge of recreation development, but I was still under Pink Arnold's guidance, making plans for picnic and campground developments throughout the Region. With the rapid increase in the CCC program and the number of camps, which I believe got to number up around 40 during the 30's, we were pretty busy making plans and developing camp and picnic grounds for all the National Forests. In fact, some of the improvements are quite serviceable."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap14.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008