|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER IV

New Rangers

After the Bureau of Forestry was transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture in 1905 and renamed the Forest Service, applicants for Ranger jobs (who had to be between 21 and 40 years of age) were required to take an examination. The first examinations under the new regime were held on May 10 and 11, 1906, throughout the West.

One of those pioneer Rangers, Henry L. Benham, who started work in 1907, was interviewed at his home in Williams, Arizona, and was asked about those early examinations.

"Well," he said, "we had a little written test to find out what we knew about surveying, if anything, and mining. It wasn't too big a test. What they wanted to know mostly was whether a man was able to ride the range and see that the cowmen and the sheep-men stayed on their own allotments.

"I had been riding for Will C. Barnes until he sold out and moved away from New Mexico. Mr. Barnes went into the Forest Service and he wrote me and asked me why I didn't apply for a job. . . .

"They gave you a paper about the duties of a Forest Ranger, and it was a pretty good description. You had to ride and be able to take care of yourself in the open in all kinds of weather. After they gave me the written test I had to saddle a horse and ride out a certain distance in a walk, then trot over to another station, then lope back to the starting point. After punching cows for six years, I didn't have any trouble qualifying.

"Then they tested to see what you knew about handling a gun, so you didn't go out and shoot somebody with it the first day. And you had to put a pack on a horse, a bunch of cooking utensils, bedding, bedrolls, and a tarp to cover it with—and a rope to tie it on with.

"I'd learned all that before I went into the Forest Service. I didn't have much trouble. Some of the boys had an awful time, winding their ropes under the horse and around his belly.

"I took the examination in Denver, and in this class they were mostly right out of college. I remember one boy didn't get through the written examination before he walked out. In the olden days they wanted cowpunchers or men who were used to being out-of-doors and knew they could get along in the open."

|

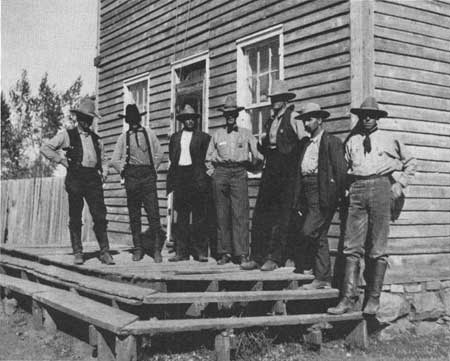

| Four Forest Rangers and three Ranger candidates on the porch of the Supervisor's Office, Apache National Forest, 1908. |

C. V. Shearer, of Las Vegas, New Mexico, another pioneer in the Forest Service, recalled the examination he took in 1911.

"It was a two-day affair," he said, "that is, there was a written examination and there was a field day. The written examination was not a multiple choice. You had to write things out—various questions. There were some about sawmills: how many men does it take to run a 10,000 foot mill? What are the positions of these men? What do they do? What kind of timber grows where? And, one question was, 'How would you fight a ground fire?' 'How would you fight a surface fire?' And 'How would you fight a top fire?'

"I remember one fellow taking the examination; he was just eating tobacco by the plug. He had a big spitoon by him. And he was busy writing and spitting and writing and spitting. Everything was quiet in there, not a word said. When he comes to this one about fighting forest fires, well he couldn't hold it any longer. He broke out, "How'd you fight a top fire? There's only one way; I'd run like hell and pray for rain!'"

Shearer's introduction to his new job as a Forest Ranger would have been enough to turn a young man to soda jerking or clerking or some other less-demanding job. But Shearer remained with the Forest Service for several years, then took a position as farm manager of the Los Alamos School for Boys. He later joined the Soil Conservation Service and remained with that agency until his retirement.

His appointment as an Assistant Forest Ranger on the San Antonio District of the Carson National Forest came through in November, 1911. Shearer started from his home in Las Vegas with a team and a buggy, accompanied by his mother and sister, food, bedding, two hound dogs, a cat, and a bowl of goldfish. The entourage got beyond Mora the first night, then to Black Lake the next. Between Black Lake and Taos they had to traverse a snow-covered road that was straight down the steep side of a mountain. Snow had been scooped out "higher than our heads" and it was extremely icy.

"Those two horses had to hold back," Shearer remembered. "The brakes I had on my buggy wouldn't hold anything. The wheels would just slide on the ice. We had come to this place so suddenly I wasn't able to stop and let my folks out. These horses set back in the breeching, and that buggy going down the hill—the old buggy tongue was turning into a bow. I sure thought it was going to break. If it had, why we'd have run into the horses and been scattered all over the bare slope of that mountain. But those horses set back and slid along, holding all they could until we got to the bottom. What an experience."

Shearer and company got through Taos and on to Tres Piedras without more problems until they reached a point near the settlement of No Agua.

There, the temporary guard was to have met Shearer and guided him to the station. When no guide arrived, Shearer decided to try to find the station himself. After several false starts, when it was getting late in the day, he bedded down his mother and sister under some sagebrush beside a snowbank and set out to find the station by following a telephone line.

"I left the dogs with mother and sister, to sleep with them on the bed and keep them warm, and hoped the cat and the goldfish would live through the night. I spent the night following the telephone line, and Lord, we got into snowbanks. I finally came onto the road that I knew would take me to the San Antone. So I headed back to the camp along about daylight. The folks had spent the night in fair comfort and were all right. They got up to get something to eat, then I had to look for my horses. They had disappeared. It took me till noon to find my team. We started up to the station and finally got there before dark, about sundown.

"The snow was knee-deep and the guard wasn't around. The door was open so I walked in. Finally rustled up some wood, got a fire going in the little old stove in the far end of the kitchen. We were about out of food, a few pieces of bacon, a few pieces of bread, and I think some prunes. Maybe a can of beans and a can of sardines. Mother started seeing what she could make out of the provisions we had, and it was enough for supper. But it was a bleak night, I promise you that. I looked out the window, and here comes a fellow with a pack horse. I was getting ready to go out and hail him when he turned in. He happened to be the fellow that took the Ranger examination same time I did. He was Ranger on the District south, and he was out looking for horses. Anyhow, he unloaded his pack. He had lots of grub and set us up to a fine supper. Next day he took me around to the sawmill and to Ortiz, where we could get some groceries. You know, I never was so glad to see a human being in my life as I was to see him ride up that night, because we were in desperate circumstance.

"We had been there a few days when the telephone line went down, and winter really set in. Snow drifted up over one side of the station. When I went down to the barn to feed my horses, I had to walk the fence and beat the trail on snow three and four feet deep. "I had skis there, and I improvised a little sled. About once or twice a week I'd go to the sawmill—about five miles—on these skis. I'd throw some grub on this little sled, snowshoes would have been better, but I made out. We lived out the winter that way until it began to open up, and I could get on a horse. We didn't see a soul again that winter 'til along toward spring.

"Along toward spring I was transferred to the Las Vegas District, and they sent a man—Roland Lynch—to take my place. I worked with him about six weeks to break him in before I left.

"There were about 86,000 head of sheep permitted on the District. They had been used to running 'em free and open. They didn't like the Forest Service. It was new and they fought it every way possible. When I was trying to divide up the lambing grounds and apportion out the ranges, they told me to go to hell right along.

"There was a big politico up there—a fellow named Antonio. He went down to see our Supervisor, C. C. Hall. He went in and told Hall, 'We're tired of the Forest Service and the way the Forest Service is doing. We're tired of having your man up there telling us what to do. We want you to move him out of there. If you don't move him out, he's going out in a box.'

"Hall told him that if anything happened 'to our man up there, you fellows are not going to be able to escape the law.'

"'The law? We're not afraid of the law,' Antonio told him. 'We'll take care of that. Just remember this, if you keep your man up there, we're gonna have trouble. It's not gonna be easy. Plenty of witnesses. Suppose your man would be able to kill a few of us, we'd have enough witnesses to hang him.'

"Hall got up from his chair and faced Antonio. 'Antonio,' he said, 'I guess we've talked it out. There's just one more thing to say: If I or any of my men ever get into trouble with you or any of your men, when we get through with you there won't be a damn witness left.'

"Well, that was the tempo of the times and the spirit of breaking in the new man.

"Another time we had a meeting in Ortiz. We were discussing grazing permits and were taking applications, when a big fight came on. Finally, a group of 'em got up and began to call us sons of bitches and all that. We just got up and left the meeting immediately.

"But I went to the village and wrote up applications, and I made a point to do it in Antonio's store. I'd stand at the counter and write 'em up. Antonio would call me names and tell me what the Government was doing to them, and I didn't know whether I was going to have a fight on my hands or not. Somehow or other things passed off without a showdown.

"There was a later showdown there in the store one time. He made some remark, called me a name I didn't like, so I went up to him and told him to apologize and say it was a slip of the tongue. He said he wouldn't. So I just reached over the counter and grabbed him by the collar and pulled him back across the counter. I had one of these old carrying cases they used to have, canvas bags in the old days. Mine was loaded with books. I got him across the counter and I come down with that and I give him a rap on the butt with that thing as hard as I could. I turned him loose, and I said, 'Now, be more careful of your language after this,' and I walked out. I saw him after that but it was never mentioned. Never another showdown. Just an incident that passed by. But that was the way we had to get along in those days."

|

| Forest Ranger's Meeting, Douglas, Arizona, 1908. 1. D. D. Bronson, 2. R. E. Benedict, 3. Arthur Ringland, 4. Walter Edwards, 5. Robert J. Selkirk, 6. H. D. Burrall, 7. George Cecil, 8. Jim Westfall, 9. R. A. Rodgers, 10. Henry De Laney, 11. Stewart, 12. E. H. Clapp, 13. This number not on picture, 14. Roscoe S. Willson, 15. L. F. Kneipp, 16. A. H. Zachau, 17. W. R. Mattoon, 18. Jones, 19. Bill Earle, 20. Neil Erickson, 21. T. S. Woosley, 22. Murray Averett, 23-24. Don S. Sullivan, 25. M. W. Hockaday, 26. Frank A. Krupp, 27. R. S. Kellogg, 28. Birtsall W. Jones, 29. Birdno 30. Arthur Noon, 31. Moody. |

Although Elliott Barker also served as Ranger on the Carson, he did not encounter too many problems in carrying out his assignments, and he recalls that because he could speak Spanish it contributed greatly to whatever success he enjoyed on the Carson. About four-fifths of the people he dealt with were Spanish-speaking.

"I was a Ranger at Servietta that first winter (1912), a little place 12 miles south of Tres Piedras on the D. & R. G. Railroad," he said. "We had no water there except what the railroad company hauled down in water cars. They had a tank car and we had to water horses from that. In the spring of 1913, I was moved to the Cow Creek Ranger Station, eight miles west of Tres Piedras. There we were very happy. Our oldest son was a year old. We had a three-room cabin that was quite comfortable in the summertime, but the chinking wasn't very good and the floor consisted of just 12-inch board with cracks about a quarter of an inch wide.

"We got an old carpet to put down on the floor so we could put Roy down and let him crawl around a little bit but when the wind would blow it would hump up like he had an elephant under him. But at any rate we got along. There was no inside plumbing at all. When I had to be gone for several days, as I frequently did on my Ranger District work, my wife had to draw water from the well and carry it to the house. She had to feed the horses, the extra horses, and she had to milk the cow and take care of everything around. Sometimes that country gets really cold, down to around 20 or 30 degrees below zero in the wintertime, but we got along fine and had no trouble at all. We were very happy there.

"Our big job at that time, in addition to handling two or three timber sales that we had going on, and the usual routine from free use permits and all that sort of thing, was managing the grazing. There was a lot of stock on the Carson Forest at that time. Far more than there should have been. As a matter of fact, during 1913-14, three-tenths of one percent of all the sheep in the United States summered on the Carson Forest for a period of three to four months.

"Naturally we were having to initiate programs to put into effect programs of reduction of stock to the carrying capacity of the range. That wasn't easy to do. It caused a lot of resentment from the permittees. While we were there, conditions were not what we could call really rugged or rough, as they had been at Cuba; still there was a pretty salty element to contend with.

"Not only that, but politicians were always on your neck whenever you tried to do anything about it. I think they are to some extent the same today toward the Forest Service when needed reductions are insisted upon. We had the political pressure on us all the way. At any rate, that was the program that Leopold had started. Supervisor Raymond E. Marsh succeeded him in, I think it was the latter part of 1913. Leopold had become ill and took a couple of years' leave. We were trying our very best to get the stock reduced down to a lower number and we were making a little headway."

Barker became Supervisor after Raymond Marsh was transferred to the Coconino in July, 1917, and remembers that World War I "disrupted a great many plans and programs, took lots of men from the Forest Service.

"I lost several Rangers," Barker said, "and the worst thing that happened to us was that we got orders from Washington to take care of just as many additional livestock as was applied for to aid the war effort—to produce meat, to produce more meat. Well, it was a short-sighted policy because it didn't actually aid the war effort. By the time they got around to producing more meat the war was over. Human nature being what it is, people wanted to take advantage of getting their stock on the Forest and keeping it there. So, at the end of the war we had more stock on than we had back when Leopold tried to start to reduce it—and that was a very bad situation. Some of our areas had become badly overgrazed. Then the stock market bottom dropped out and there was no market where people could sell their sheep or their cattle.

"You told them they had to get off the Forest, and they said, where the heck would they put them, where could they go? Many of them went broke. One of the biggest sheep permittees I had—I think he had 23,000 head on the Carson—went around back of his newly-built garage and blew his brains out. . . . There were many others who went broke, and we caught the blame for a lot of it by having to reduce the number on the Forest.

"It went that way through the war period. We had to do double duty and it was pretty tough going. The toughest situation that we had came in the fall of 1918 when that terrible epidemic of influenza hit the country. Taos, it was said at that time, was the hardest hit of any community in the United States. I was chairman of the Red Cross for Taos County and therefore shouldered a great deal of work in connection with the influenza epidemic. We turned the church and the schools into hospitals. We got six doctors and nine nurses from St. Louis to help us out, but they were virtually helpless as to what they could do for the people.

"I closed the Forest Office for something over 30 days. We didn't even open the door, didn't answer any mail, didn't get our mail. I lost my chief clerk and janitress; others were very ill with the flu. I got by until November 9. Nearly everyone else either had it and had died or was getting well and over it. I came home one night at midnight from one of the outlying communities we were trying to help out. About 2 o'clock I woke up as sick as I ever was in my life. I was unconscious for nine days. I didn't know for two weeks afterwards that the Armistice had been signed.

"I was supposed to die, but I didn't. They pulled me through somehow."

Barker recalls that the illness left him depressed and discontented, and in the spring of 1919—against the advice of Regional Forester Paul Redington, he resigned to go back into ranching and eventually into the State Department of Game and Fish where he achieved a national reputation for his work as State Game Warden.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008