|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER V

Fire!

When the Forest Reserves were created, the most responsible work of the early Forest Rangers was undoubtedly fire fighting and fire protection. Before the creation of the Forest Service little organized effort was undertaken to fight fires.

There had been many bad fires in the Southwest that had devastated thousands of acres. On the mountains above Santa Fe a fire had raged for weeks in the 1880's. Nothing was done to fight the fire; it was allowed to burn itself out, destroying tremendous acreage of natural resources. Today the snags of that old fire and burned-over areas may still be seen on the high mountain side.

The principal instruction given to new Rangers was to patrol their District and watch for smokes. The Use Book (the manual of instructions) directed that "Officers of the Forest Service, especially Forest Rangers, have no duty more important than protecting the Reserves from forest fire."

"Generally the best tools for fighting fire are a shovel, mattock and ax," the Use Book pointed out. "The Ranger should always carry at least an ax during all the dangerous season."

The Use Book listed these general principles for fire fighting:

"Protect the valuable timber rather than the brush or waste.

"Never leave a fire, unless driven away, until it is entirely out.

"Young saplings suffer more than old mature timber.

"A surface fire in open woods, though not dangerous to old timber, does great harm by killing seedlings.

"A fire rushes uphill, crosses crest slowly, and is more or less checked in traveling down. Therefore, if possible, use the crest of the ridge and the bottom as lines of attack.

"A good trail, a road, a stream, an open park check the fire. Use them whenever possible.

"Damp or even dry sand or earth thrown on a fire is usually as effective as water and easier to get."

On the day that Tom Stewart started his assignment on the Pecos Reserve in 1903, he rode to the top of the mountains to look at his District. The first thing he saw was smoke from two forest fires.

"I scratched my head and cussed," Stewart said, "and decided to handle them one at a time."

For help on one, in the Sapello District, he rode fast to Rociada. Ranchers there had seen the smoke and were already gathering tools when he arrived, so they hit for the Sapello. The fire was controlled by next morning.

Without any sleep, Stewart then rode to the other fire, about two miles from the village of Agua Negra.

Stewart rode into the placita, sought out the alcalde (justice of the peace) and asked for his help to get men to fight the fire. The alcalde at first was curt and brushed off the request: "I don't give a damn if the whole Forest burns up."

Stewart let loose a stream of fluent Spanish, telling him that the people of the village were users of the Forest, that they would be hurting themselves to let the Forest burn, and that it was their duty to help put out the fire. He finally convinced the alcalde, who then got on his horse and began to round up volunteers. In no time he had collected 15 or 20 men.

"We worked from about 3 p.m. to 3 a.m.," Stewart said, "and we got that fire under control. The alcalde agreed to stay in charge of the men. And you know, after that he was the best cooperator I had in my District, right up to the day of his death."

Roscoe Willson used to enjoy telling about how he had seen Halley's Comet while he was fire fighting.

"We had a big fire up under the Mogollon Rim above Pleasant Valley," Willson recounted. "That was in 1910. I went up there from Roosevelt and got the boys. We got some cowboys too. It was mostly a ground fire. I remember fighting the fire there with the boys. They were keeping it under control, so I took an old quilt and rolled up and laid down. I looked up and could see this Halley's Comet just as plain. It was streaking the whole sky."

Edward G. Miller, who made a life-long career of the Forest Service until his retirement as Chief of the Division of Lands of the Regional Office, reminiscing about his early years in the Service, recalled some incidents of fire fighting.

"When he was Ranger on the Flagstaff District, Ed Oldham had complete fire crews organized from settlers," Miller related. "I can still see George Moore, with a plow in his wagon, driving his team on a long trot toward a forest fire. You didn't have to send for him; he watched for smokes and was on the way as soon as he saw one. The same was true of a lot of those per diem guards, men who were not part of the regular firemen's or lookouts' organizations. They were appointed as supplementary guards to go to fires when they saw one, or when called upon by the Ranger or his assistant. We used some Indians back in those days, but crews hadn't been organized as they are today at the various Indian pueblos, on the Navajo Reservation, and in some of the Spanish settlements. We depended largely upon the work crews at the lumber camps. All the brush crew were trained in fire fighting. Also a lot of the men around the sawmills had fought fires so often and so much, they were first class hands."

|

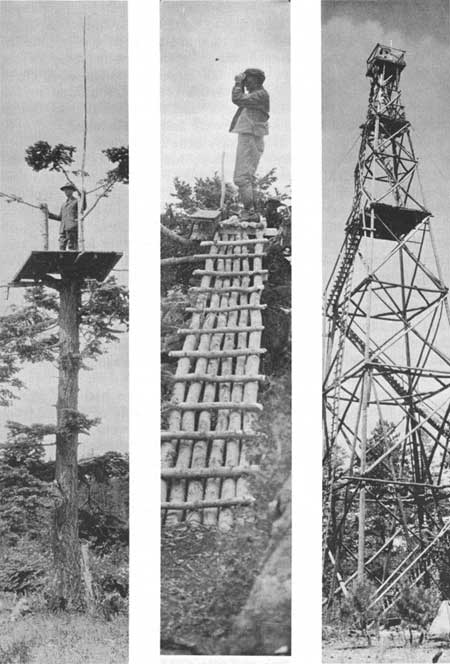

| A monkey would have felt at home on early-day National Forest fire lookout towers. |

The early fire guards had very little equipment to work with in fighting fires. Henry Woodrow, long-time Ranger on the McKenna District of the Gila National Forest, remembered that when he was first assigned as fire guard in 1909 "all the instruction I had was to go up there and look out for fires—and put them out."

"I packed my outfit, which consisted of chuck and bed, on one horse," Woodrow recounted. "No tools were furnished me. I took my axe and a shovel—all the equipment I had with which to fight fires. No tent was furnished. The first fire I had occurred on the West Fork of the Gila above the mouth of Turkey Feather Canyon. I rode to the fire and found an old prospector camped near there by the name of Beauchamp. He was an old timer in the country, and he already had part of a fire line started around the fire, which by this time was burning half way up the side of Turkey Feather Mountain.

"Later in the evening Robert Munro, who had just started work as forest guard, and a Ranger by the name of Shanks from the Datil Forest, arrived. At that time there were no telephone lines in the mountains so we had to rely on a messenger to carry the news and gather up men. Some time during the night Ranger Stockbridge with two firemen from Apache Cabin came to the fire. Next day Forest Ranger Herbert Fay from Mogollon with a bunch of men, Bob Reid from Alma Ranger Station, Fred Smith from Gila Station, Frank Andrews, Deputy Supervisor from Silver City, all were there. By this time the hard wind had carried the fire all over the south side of Turkey Feather Mountain and was finally corraled along the top of the ridge.

"When this fire was under control, another was discovered in McKenna Park which I, with three other Forest Officers, soon got out. Then another was discovered at Pryor and one on Little Creek south of E-E Corral. The one at Pryor was soon put out— about 100 acres. The one at Little Creek burned over about a section. Forest Ranger B. H. Cross, from Pinos Altos Ranger Station, came to this fire with several men and cowboys from the Heart Bar Ranch. Other Forest Officers on this fire were Deputy Supervisor Frank Andrews, Rangers Bob Reid, Robert Munro.

"When this fire was controlled still another fire was discovered on head of Mogollon Creek where the trail now crosses to Sycamore and Big Turkey Creek. We went to this fire, that is, Frank Andrews, Bob Reid, Robert Munro, Fred Smith and I. Later in the evening Rangers Stockbridge and Fay, and two fire guards came and we started work on the fire during the night. Next day several cowboys came in from Cliff but the fire kept traveling southwest at a rapid rate. We kept it from going north across Mogollon Creek. Finally, on July 4 a light rain came and checked the fire. Next day all the men went out except one fireman and me. In a day or two he went out and left me to patrol. I kept patrol around the fire and kept it from breaking out. I kept this up until July 23 when a general rain came and put it all out. This fire burned over approximately five sections."

When the call comes for fire duty, it takes precedence over everything else—even a dish of long-awaited, mouth-watering ice cream.

That was the experience of Edward Ancona, another career man in the Forest Service, now retired. He was telling about the time he was serving as Ranger on the Crown King. It was hot there in the summer time. The only way they had to keep things cold was to hang them down the well. Ice was almost unheard of. But one hot summer, arrangements were made to ship in some ice.

"That was the only time I ever got mad, really sore at my job," Ancona said. "An old fellow had some cows there in the Basin, and he had saved the cream for about a week or two to make ice cream. The shipment of ice arrived, and the ice cream was made, and we were all at this party. We were just about ready to serve the ice cream when a fellow rode up outside and knocked on the door. 'Is the Ranger here?' he called out. I scringed down in my chair, but somebody answered, 'He's over there.' He looked over at me. 'Well, you've got a fire up on the ridge up above here. Lightning just struck a big pine. I can see it from my place.'

"The call of duty was stronger than that of the ice cream. I had to leave—and that's one of the big regrets of my life. I went out and sat by that burning tree all night while my friends were eating up the little ice cream that there was—the only ice cream in Crown King in two years.

"But I put the fire out, by golly. I sat by it until there was nothing left of it."

Over on the Catalina District, Stanley Wilson was building a log fire-lookout on Mt. Bigelow. It was a pretty rugged job, putting up the poles and an eight-foot platform forty feet up. So when Wilson and Frank Howe came in tired on Saturday night, they were saying how glad they were next day was a holiday.

"If there's a fire, I wouldn't go to it," Wilson said.

"Wouldn't you really, Stan?" Howe questioned.

"Of course not. Tomorrow's a holiday."

Then Wilson remembers that when they got to the cabin, word came that there was a fire.

"So, of course, we started off to that fire. It was a little different from what you start with now. We started to the fire, myself and Frank Howe, and a kid named Pick and an old fellow by the name of Henry Hiller.

"We started afoot down the ridge on the back side of Bigelow, which was pretty rough country, carryin' shovels. Pick was a big awkward kid, and every once in a while he'd lose his shovel, and Frank Howe would say, 'Stan, Pick's lost his shovel.' We'd stop and dig up his shovel for him. Well, finally we got to this fire—it was between Edgar and Alder Canyons—on the east side of the Catalinas, and we started at the top of the ridge between 'em. I said, 'Frank, you and Pick take one side and Henry and I will take the other.' Well, actually we were whippin' with pine boughs, not usin' our shovels. The last thing I heard of Frank Howe and Pick, Frank said, 'Stan, Pick's lost his shovel, so how the devil do we fight the fire?' I said, 'Go ahead and fight the fire.' So we fought that thing and we were doin' pretty well 'til about 10 o'clock in the morning when the wind began to whip up. Well, Henry Hiller was quite an old man, and he slipped and slid down the side of the hill. A little tongue of fire got away from him, and that was that. It went then for another week and burned 5,000 acres. There were many, many people on it before it was finally put out. Now that's particularly interesting to me because later on when I was in the Regional Office, we had a quota out here of 7,000 acres for the whole Region—and I had burned most of that quota in one fire in my day!"

Paul Roberts remembers that when he was Supervisor of the Sitgreaves National Forest there were a few incendiary fires on the Lakeside District. Clarence Shumway was the Ranger there.

"Everybody knew him, so I figured that he'd have a hard time detecting the culprit," Roberts said. "I had Bill Freeman, who was a resident of Snowflake, and Bill always liked to work for different Federal agencies, so I had Bill play detective and go up there and see if he could find, or apprehend, the incendiary.

"Bill went up and spent about a week up there, and thought that he had discovered the culprit. He went to McNary where the JP was located then, to make arrangements to bring the fellow into the JP and have a hearing. Well, while Bill was tellin' the JP about the case, the JP became very interested in it and after a while he said to Bill, 'Well, how much shall we fine him?' Bill said, 'We haven't found him guilty yet.' And the JP said, 'Oh, Hell, he's guilty all right. It's just a question of how much we'll fine him.' So Bill took him in the next day, I think and the JP fined him $25 and costs. Well, $25 happened to be all the money the fellow had and of course that didn't leave the JP anything, so he rescinded the $25 and fined the fellow $22.50, plus $2.50 court costs!"

Another problem Roberts recalled was the danger of fire from some of the farmers who would want to smoke out bees in a bee-tree.

"We had one case on the Pinedale District where a fellow smoked out the bees, but he hadn't put his fire out and the fire spread a little bit. Dolph Slosser, who was a pretty good detective, went over and saw horse tracks. Dolph could read horse tracks as well as he could read writing. He started sleuthin' around to find out who'd been up there. He was sittin' on the corral one day talkin' to this fellow. He denied that he had any thing to do with the fire. Dolph looked down at a horse track and recognized it as one of the horses that had been tied up there near the fire. He said, 'Well, Bill, (or whatever this fellow's name was) that horse track is the same track that was up there at that bee tree.' So the fellow admitted. 'Well, that's mine all right.' He hesitated, then he says, 'There ain't no law against lyin' a little to keep out of trouble, is there?'"

When O. Fred Arthur* was Supervisor of the Lincoln National Forest he had an incendiary fire that had tragic consequences.

*O. Fred Arthur started as a Forest guard in 1907 on the Prescott National Forest. He retired in 1947 as Supervisor of the Cibola National Forest.

There had been two incendiary fires on the Lincoln in March, 1927, and on March 15 another was reported in the Capitan area. Ranger Willard Bond left Baca Ranger Station for the fire and took with him A. R. Dean and Lloyd Taylor, Dean's son-in-law and foreman of the Block Cattle Company, whose range extended over the fire area.

Dean offered to drive them in his car, which they loaded with supplies, including also a rifle and six-shooter. In Capitan, they met Ranger Lee Beall from the Mesa District with some firefighters.

The two groups drove up into the mountains, stopping at a closed gate in front of the T. H. Shoemaker house. They left the cars parked near the fence and went on afoot across the hills to the fire. Later in. the day a fire camp was established, and about 2 a.m. Ranger Bond walked back to Ranger Beall's car to move it to the fire camp, about two miles farther east. Then along toward morning Lloyd Taylor, accompanied by a couple firefighters, Charles Pepper and Apoliano Romero, returned to Dean's car to pick up additional supplies that had been loaded in it at Capitan.

Pepper was carrying a lantern, standing at the rear of the car. Taylor was getting some things from the front seat when two shots were fired from the vicinity of the nearby Shoemaker house. Pepper felt a sting in the back of the neck. Later they decided it was a sliver from a piece of rock, struck by one of the bullets. Pepper immediately dashed out the lantern and all three ran for the brush. A bit later, Taylor quietly made his way back to the car to get the equipment, then they returned to the fire and reported the incident.

After daylight, Taylor and Dean returned to the car to move it to the fire camp, and they discovered that the rifle and six-shooter that were in the car had disappeared. They discovered also that the car had two bullet holes. One had entered through a front curtain, passing through the back cushions. The other had hit the running board, damaging wiring directly underneath the car. Both bullets had narrowly missed Taylor, one apparently went a few inches above his body and the other a few inches below as he stooped to get something from the front seat.

Later on in the morning, the Rangers sent word to Supervisor Arthur at Alamogordo that some shots had been fired at the firefighters, supposedly by Shoemaker in front of whose house the cars were parked.

In his report to the Regional Forester later, Arthur wrote that he had been advised that "a little evidence had been collected already identifying Shoemaker with this fire."

"I then called Mr. French, Assistant Solicitor at Albuquerque, and told him in a general way what had happened and requested that he come down and assist in the collection of additional evidence and prosecution of the case in event such action proved warranted."

Arthur decided to go to the fire and left about 1 p.m. in a Forest Service truck and took with him W. C. White, executive assistant, who had previously served as Ranger in that District. That night they met Solicitor French in Capitan, and drove out to the fire area at daybreak to interview the parties concerned with the shooting. Pepper, who had been nicked by the sliver of rock, did not want to press any charges, and evidence regarding the incendiary fire was insufficient for a government case.

"Mr. French and I decided that in the event complaints were made and search warrants issued for the stolen firearms, the matter could be turned over to the local authorities, which would provide sufficient time for the government to go ahead in the collection of evidence," Arthur wrote in his report.

"Ranger Bond said he was anxious to recover his rifle, and stated on his own responsibility he would make a complaint and request a search of Shoemaker's premises.

"We therefore left with him and drove to Carrizozo, reaching there about 6 p.m. and talked the matter over with the justice of the peace and Sheriff Sam Kelsey. A search warrant was issued, which Mr. Kelsey said would be served the following day."

Before they left the office, Arthur got word that Lloyd Taylor, Dean, and Pepper were coming to Carrizozo and to await their arrival. It turned out that Dean was pretty much upset when he returned from the fire to find his car damaged and the guns stolen and talking it over with Taylor and Pepper, they decided on their own initiative to make the necessary complaints. So an additional warrant was issued, charging assault with deadly weapons.

The following morning Sheriff Kelsey and his deputy, Pete Johnson, arrived in Capitan and a strategy meeting was held with the Forest Service officials.

It was decided that the Sheriff and Dean would first go to the Dixon Ranch, because Dixon was supposed to be on friendly terms with Shoemaker and they would try to persuade him to intercede with Shoemaker to give himself up to avoid bloodshed. The deputy sheriff and Forest Rangers and ranchers were deputized and assigned to designated places to determine primarily the whereabouts of Shoemaker so that if Dixon could not get him to surrender, the Sheriff and Dean would make the arrest.

Arthur and Deputy Johnson were assigned to the nearby Koprian Ranch, and at the fire camp they picked up White, Arthur's assistant, and a pickup truck which White drove. White and Deputy Johnson sat in front, both with rifles, and Arthur sat on a spare tire in the back of the truck.

"Reaching the highway about a mile and a half away we turned west toward Encinosa," Arthur said in his report. "As we rode down a hill, at the bottom of which a side road leads down from the Shoemaker Ranch and passing the Hipp Ranch joins the highway, I looked ahead and saw two horses at the mail box, on one of which was a woman. I do not recall seeing anyone else, but the thought occurred to me that possibly the other horse belonged to Shoemaker. Because of their position and, also, because of mine in the rear of the car, we drove past them before I noticed the other party, who proved to be Shoemaker. He was standing alongside his horse, near the butt end of his rifle which was in a scabbard hanging on the left side of the saddle, the butt in a forward position. Going about 100 or 150 feet, the car stopped and Johnson got out and started walking back on my left side; my back being toward the front end of the car. My attention was concentrated on Shoemaker to see that he did not make any movement. I cannot say exactly how far Johnson had gotten when Shoemaker reached for his rifle. Johnson whirled and started back. I then noticed that he carried no firearms. He said, 'Look out, he is going to shoot.' My gun was on the bottom of the car at my side. I grabbed it and jumped out on the right hand side and ran around in front of the car. White remained in the seat. Shoemaker started shooting. I fired also. Johnson grabbed his rifle quickly, took his position on his knee in front and at the left hand side of the car. I recall his saying, 'Throw up your hands, Shoemaker.'

"Johnson was directly in my line of fire at Shoemaker. I could not do much shooting without exposing my entire person, while Johnson remained in a way protected. I did not fire over three shots if that many, Shoemaker was firing rapidly. My time was spent trying to shoot from underneath the car. During this time my attention was distracted from our main purpose twice; once seeing White slip down into the seat, and it occurred to me that he was shot. Immediately afterward I decided that he was slipping down out of the way of the bullets; the other time was when he pitched forward on his face in the rut of the road directly in front of the car. I further noticed during that time that the woman on horseback had pulled out to the north side of the road, sitting on her horse and viewing the entire scene. The firing stopped and I saw Shoemaker laying face downward on the ground. Johnson started toward him, I returned to White. Immediately upon going back I saw Shoemaker crawling for his rifle. Johnson hurried back and asked if I had any shells left in my gun. I replied there was, he said, 'Give it to me,' which I did. He ran back and when about halfway, Shoemaker was within five or six inches of his rifle and reaching for it. Johnson fired a shot which ended Shoemaker's life. The saddle horse had been shot and was staggering around on the north side of the road. Johnson went over and finished him.

"Johnson came back and we gave our attention to White. His face was terribly mutilated, and I saw no hopes for him. Johnson said we would put him in the truck and rush him to Ft. Stanton, 25 miles distant. I replied that there was no use, that the radiator had been shot to pieces and that we could not go over a mile, but for him to remain there and I would rush back to camp and get another car. Before leaving I went over to the woman and asked her to please ride to the Hipp Ranch and tell them to come down. I got out and started running to camp when I met French and Strickland and others who had not left the camp. We got in French's car and went to the shooting and found that Johnson had left with White in the mail car which had passed along directly after I left. Newt Kemp was at the scene. We let out one or two parties and Strickland, Boone, French and I drove on. . . .

"An inquest was held over Shoemaker's body, at which time the woman's testimony was secured. She proved to be the wife of Mr. Guy Hix, a Block cowpuncher. I was not present at this hearing, but my testimony and that of Mr. Johnson was taken that night before the coroner's jury.

"In closing I might add that the guns covered by the search warrant were afterwards found in the Shoemaker house."

White died at 9:30 p.m. on Friday, March 18. Ironically, when he was a Ranger on that District he had been threatened several times by Shoemaker. Whether Shoemaker knew that White was in the cab of the pickup is not known, of course. Shoemaker may have been merely firing blind at the back of the truck. Newspaper reports of that day said five slugs of soft nose bullets had pierced the rear, and it was regarded as a miracle that Arthur and Johnson had escaped.

The Associated Press reported that Shoemaker was alleged to have refused to make payments to the Forest Service on his land, that he generally opposed the Forest Service and had boasted that he set fires in 1925 and 1926 as well as the fire then raging, which required about 75 men to control.

Forest fires have plagued the Forest Service since the inception of the organization—but constant vigilance has resulted in a splendid record of fire protection.

After he became District Forester in 1908, Arthur C. Ringland began to plan a program of increased fire protection for the Southwestern Region.

"The logical way to bring this about," Ringland wrote to his Supervisors in Region 3, "is by a careful study of the conditions on the Forests and the adoption and use of a definite fire plan."

|

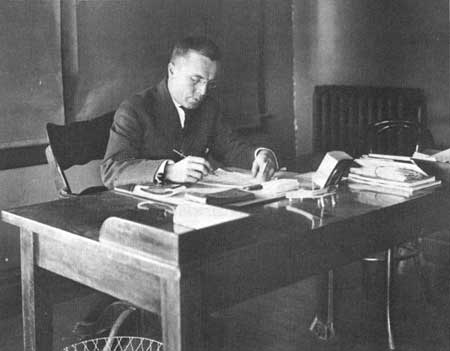

| Arthur C. Ringland, first Southwestern District (Regional) Forester (1908-1916) pioneered fire planning. |

Among the suggestions Ringland made were construction of lookout stations on high peaks, construction of telephone lines from lookout stations to Ranger's or Supervisor's headquarters, construction of trails for fire patrol and roads for rapid transfer of firefighting forces, placing in strategic locations tool boxes and firefighting tools, and provision for volunteer and hired firefighters.

|

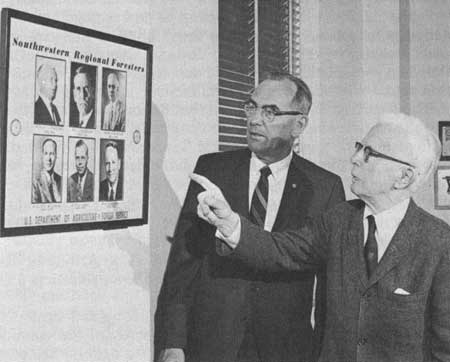

| Ringland and Southwestern Regional Forester Wm. D. Hurst, Regional Office, Albuquerque, New Mexico, May 15, 1972. |

And as a closing note, Ringland wrote that "I feel that it is an important part of good administration to make Rangers, who bear the brunt of the hard work in firefighting, feel an intense interest in the preparation of the plan under which this fighting must be done."

Ringland had been a Ranger,* so he knew the job from the Ranger's viewpoint. The Forest Service's long-standing policy of promotion from within the organization, which resulted in so many early Supervisor appointments from the ranks accounted for the close-knit spirit of teamwork that marked the early years of the Forest Service.

*Ringland was one of the original group of students recruited by Gifford Pinchot at the turn of the century, and in 1905 when he graduated from the Yale School of Forestry, he became a charter member of the Forest Service. He began his career as a Ranger on the Lincoln National Forest and was appointed District Forester, with headquarters in Albuquerque, effective Dec. 1, 1908, serving in that capacity for eight years. He went on to an important career in the Federal government after service in the AEF during World War I, then in charge of mass feeding of children of Czechoslovakia by the American Relief Administration, directed by Herbert Hoover, and the relief and evacuation of White Russian refugees in Constantinople in cooperation with the League of Nations, 1922-23. In succeeding years he held numerous high government appointments in the Department of Agriculture, the World War II Relief Control Board, and the Department of State, retiring from that agency in 1952. At the time of this writing (1972) he was living in Washington, D. C.

Paul Roberts who had worked as a grazing inspector and as Supervisor of the Sitgreaves National Forest in the 1920's, put it this way: "It was a period of tremendous crusading spirit; I don't know whether the Forest Service could ever get that same type of thing going again or not, because a lot of those fellows that had the crusading spirit didn't know anything about forestry. They were ex-cowboys and lumberjacks and all that sort of thing, but they believed in it. Most of 'em went into it because of the spirit of adventure and because it was something worthwhile. It took a hardy breed to do the job and they did it. Whatever their faults and failures, they still did a tremendous job of getting the Forests established and going."

Today the Forest Service has a couple other rugged breeds of fellows working for them and fighting fires. These are the professional smokejumpers and the Indian and Spanish-American villagers who have been organized into professional year around firefighting groups, on call at the sound of the telephone ring any time of day or night.

|

| The organized "Southwestern Firefighters" are famous for "hitting 'em fast and hard" throughout the western states. |

The Forest Service discovered years ago that an organized crew was much more efficient in fighting fire than a pick up crew of volunteers or hired labor. Indians are particularly suited for this work since they are used to rugged country, hard manual labor, and working as a crew. Since others in their pueblos or reservations can take over their labors at home, they can leave at any time. And they may be gone anywhere from a couple days to two months.

Each of the Indian or Spanish-American groups has its own distinctive hardhat decoration and name. The first of these was the Mescalero "Red Hats" organized in 1948. Now there are picturesque designs on hats for groups from the Rio Grande pueblos, from the Arizona pueblos and reservations, and from the Spanish-American villages of northern New Mexico.

The hardhat fighters must be between the ages of 18 and 60 in good physical health, determined by periodic medical examinations.

In 1971 more than 3,000 trained firefighters, organized into 20-man crews, were available to the land managing agencies. Since the first call from outside the Southwestern Region came from California in 1950, these elite troops have battled wildfire throughout the western states.

A couple dozen smokejumpers in the Southwest operate from Silver City, close to the Gila National Forest which has a high incidence of fire over the years. Much of the National Forest and Gila Wilderness can be reached only on foot or horseback, and the use of aerial firefighters makes fire suppression quickly available.

Besides the twin-engined planes which fly the smokejumpers to the fires, aerial tankers are also used to carry multi-ton loads of slurry, a fire-retardant mixture of chemicals and water. Helicopters are used both to carry firefighters and to retrieve them and their equipment.

Gilbert Sykes, of Tucson, a long-time Ranger on three Districts of the Coronado National Forest, believes that one of the first uses of an airplane in connection with a forest fire was in 1921.

"We had a big fire in the Catalinas back in 1921, nearly 10,000 acres," Sykes said. "It came up out of the Canyon del Oro and topped out along the ridge to Summerhaven and right up to the top of Mount Lemmon and out on the San Diego Ridge. The Bureau of Public Roads had just completed a new road up the side of the mountain and we used that. Some of the fire lines stopped going around the mountain north and east, and this road made a pretty good line. Fire spilled over in a few places but the road held it in the real dangerous, deep canyons there on that side.

"Hugh Calkins was then our Forest Supervisor on the Coronado in Tucson. He managed to get an army airplane from Fort Bliss to do some scouting. I think it was one of the first times a plane had been used for aerial work on a fire—at least down in this area. Hugh made several flights over the fire. . . . He said he got a lot of good information from this aerial scouting, but the pilot flew pretty high.

"We started probably one of the first attempts at parachute dropping of supplies. It was about 1936 on the Chiricahuas. I was Ranger at Portal at the time. Charlie Mayes was an old pilot who had flown everything since about 1912. Fred Winn got him to make some tests down at Douglas. He was running a little field in Douglas at that time, out east of town. We made several drops, test drops, and decided we were pretty good. Fred Winn got the bunch up at Rustler Park to try some dropping up in the timber there at the top of the mountain.

"Fred would take a friend of his on 'show-me' trips—oh, about once a month, on the Chiricahuas. That was one of Fred's favorite retreats to get away from it all on weekends. They would stay up at Cima Park, there in the old cabin. They would take 2 or 3 horses up and would spend the weekend, he and Mrs. Winn and Johnny Ball, from Bisbee. Johnny Ball was quite a photographer. Fred wanted this officially recorded, this dropping, so he could show the boys here and there, and maybe back in Albuquerque, how good it was: Charley Mayes came over about the scheduled time and made some nice drops. We had just got some new radios at the time and we dropped one of those to see how it came down.

"It came down in good shape and we dropped a case of eggs and it came down and only a few of them broke. Johnny Ball was busily photographing each drop as it came down. One almost hit him, he was so enthusiastic, it plunked right down beside him. When he got all through Fred came over and said, 'Well, John, did you get some good shots of that?' 'I believe so,' he said, and he started to put his camera away. Then he said, 'Oh, my God, look—I forgot to take the cap off my lens.'

"So all these drops were duds—all these photographs. We didn't try it again that time. The next year we made several drops down around the Santa Rita Range Reserve trying the various size loads. The pilot and some of the boys got together and when he had made about his last drop, all of a sudden a man came out of the plane and he fell and fell and fell and his 'chute didn't open, and he plunked down about two or three hundred yards from the bunch. Everyone started running over there except two or three of us who happened to be in the know. It was a dummy they had thrown out, but it gave them quite a thrill anyway."

Improved efficiency and modern firefighting techniques have steadily diminished losses from fire, even though the number of fires has increased.

Recalling a series of fires, Robert Diggs, of Williams, Arizona, a long-time Forest Service career man, commenting on firefighting, related that "it was in 1956 that we had the Dudley Fire. Then after we got the Dudley Fire controlled—it was about 17,000 acres—we looked across to Mingus Mountain, and there she was blowing up right on Mingus Mountain. They just put the whole shooting match into a DC-3 plane and took them right on into Prescott. They took the same organization right off the Dudley Fire and put them on the Mingus Fire. That was 15,000 acres, and we nailed that one. We got home in time for a Fourth of July rest, then went right back to Safford on the Outlaw Fire.

"It is remarkable the way Forest Service crews can adapt themselves to a situation; to different Forests and different terrain, and different organizations, so to speak. They just click.

"Of course, you've got the Indian crews, and boy—those crews are fine! I don't know what we would do without them, how we would get the job done, whether it's Hopi No. 8 or Santo Domingo No. 2 or any of the others.

"Now we have the slurry planes. Those slurry planes are good. We used them on the Hell's Canyon Fire down here. We had a 500-acre fire south of Bill Williams. It could have been one of the largest in the history of the Forest Service if it had come across Bill Williams, but we nailed it."

C. A. (Heinie) Merker, of Santa Fe, a career man in Region 3 since 1923, recalled the 1954 fire on the Los Alamos Reservation as one of the most unusual he had been involved with. At the time Los Alamos was still a "secret city."

"The fire wasn't so big, but was it made into a big thing," he said. "I first saw the fire from my backyard here in Santa Fe when it started. Immediately I recognized that we were in trouble—or could be—when we found out it was on Los Alamos land.

"I sent Leon Hill over to advise them. Well, he spent the afternoon advising them. All the time they were trying to put the thing out and didn't know how to go about it. Finally, I went over. Just about the time I landed there, they came to the conclusion they had a bull by the tail. In the meantime, stories got out that the town was threatened. That got back to the Washington office of the Atomic Energy Commission, and they established a 'hot line' between Washington and Los Alamos. Then Albuquerque got word of it and they sent a whole staff up from down there. Toward evening, the powers-that-be at Los Alamos came to me and said, 'Now look, we don't know how to fight forest fires. How about you taking over?' I said, 'Who's going to pay the bill?' They said, 'Oh, don't worry about that, we'll pay the bills. Just put the fire out.'

"I got hold of Otto Lindh (Regional Forester) on the phone and told him about it. He hotfooted it up there, and Mayhew Davis (Chief of Operations) came up. Oh, everybody came up. They even drew up a written agreement as to who was going to pay for what.

"The head of technical services there, Norris Bradbury (the director of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory) stayed up the whole night. About every half hour he would come up to our headquarters wanting to know for sure that the fire wasn't going to get across the highway that runs north and south. He didn't explain what was on the other side of the highway, but every time a spark would go over there, everything was turned loose to get on that spot fire. I found out later it was some sort of explosive stuff down there. What it was I still don't know. But he was sure concerned that the fire was going to get across the highway and get into the technical area. I guess all hell would have broken loose if it had.

"We finally got the fire under control the next afternoon. Everybody and his dog were up there, including all sorts of Indians. Everybody who had come in through the gate, including the firefighters and the Indians, were registered and their names taken and they were given a badge. There was one person who got in that did not have one of those things. How he got in nobody could ever find out, but he had a devil of a time getting out. They had no record of him. He had no badge. It was Dahl Kirkpatrick, Chief of Timber Management!"

Merker said that an interesting thing about the fire was, who started it? It was learned that the sponsors of the Boy Scout camp (one of them was the fire chief) was clearing the site of old slabs and set fire to it.

"They set it off in the evening and they stayed all night watching it burn. When morning came it was pretty well burned up, and they left one man and a boy to watch it. They went to the spring there to get some water. When they got back the wind had come up and it threw a spark out, and away she'd gone. Well, the fire chief and the manager of the city had set the thing off. Boy, were their faces red!"

|

| The story of the live Smokey Bear began when a burned, frightened cub was rescued from a man-caused forest fire on the Lincoln National Forest in 1950. |

About nine-tenths of the forest fires nation-wide are man-caused, from cigarettes thrown from cars, camp fires left unattended, failure to put out fires when leaving camp or dropping lighted smokes or matches on the ground. Years ago the Forest Service began a continuing campaign to get the cooperation of the public in preventing forest fires.

Their star salesman in this campaign is Smokey. Although a fictitious Smokey preceded him, there has been a real Smokey since June, 1950. In the man-caused Capitan fire on the Lincoln National Forest in May, when 17,000 acres of forest land were destroyed, the men on the fire line discovered a cub bear that had been severely burned about the feet and was near death from shock, burns and hunger. Ray Bell, chief field man of the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, volunteered to take the cub to Santa Fe to a veterinarian to see if its life could be saved. After emergency treatment, Bell kept the cub at his home for several weeks until it was completely recovered. It was named Smokey for the poster bear of the Forest Service, State Foresters, and The Advertising Council. Then the cub was flown to Washington and presented by the Forest Service to the Washington Zoo to aid in the campaign for prevention of forest fires and conservation of wildlife.

Smokey has become an eloquent and living symbol of the need for fire prevention. Pictures of the tiny cub taken during his convalescence were used extensively in publicity, and the appealing little fellow found a place in the hearts of America's children and grownups alike.

J. Morgan Smith, who was Assistant Director of the Smokey campaign, is now Assistant Regional Forester, Division of Information and Education, with offices in Albuquerque. His collection of Smokey pictures, clippings and other material includes a number of letters addressed to Smokey.

A North Dakota girl wrote, "I read in our 'Young Citizen' that it cost billions of dollars every year to pay for the damage done by fires, so I am contributing five cents to help pay for the damage." A Burbank, California mother wrote to say that Smokey was her five-year-old son's "very best friend." "No one would dare throw a lighted match or cigarette out in the forest or mountains when he is in range," she wrote.

Another California mother wrote to Smokey to say that her son was seven years of age "and practically stands at attention when you talk on television. There is never a cigarette thrown from our car any more. We really get told!"

|

| Smokey, who makes his home at the National Zoo, Washington, D.C., is visited by people from all over the world who know his story. |

Today, fully grown, Smokey lives in the Washington Zoo and still attracts thousands of visitors. The story of his rescue from a tragic fire in New Mexico has been told and re-told in publicity stories, magazine articles, TV and radio programs and in cartoons. Forest Service officials regard the Smokey campaign as the most powerful single force in preventing wildfires in the United States today.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008