|

Men Who Matched the Mountains: The Forest Service in the Southwest |

|

CHAPTER VI

Wild Times and Wild Horses

The early days of the Forest Service coincided to some extent with the heyday of the big ranches in the Southwest, and, of course, the "big men" who ran them. One of the most picturesque was Ray Morley, of Datil, whose ranch in west central New Mexico spread over an area of hundreds of sections of range and forest land. Morley, according to his sister, Agnes Morley Cleaveland, owned two hundred 640-acre sections, controlled several times that number because of control of watering places, and additional sections under Forest Service permits.

Forest Service regulations required grazing permits under an allotment system to prevent overgrazing by unauthorized livestock.

Morley had been an All-American and captain of the Columbia football team in 1900-01 and was a man of tremendous physique and physical strength. His sister described him as "just under six feet, with broad shoulders, bewhiskered and sun tanned."

Writing in the December 1941, issue of New Mexico Magazine, Mrs. Cleaveland described him as "an amazing combination of gentleness and rugged strength. . . . He was as tender hearted as a child and as implacable as a granite cliff when he thought he was right."

Morley had many a run-in with the Forest Service before he finally came to an acceptance—though not always agreement—of the Forest Service philosophy and regulations.

"Nor was he always wrong," Mrs. Cleaveland wrote. "Typical was Ray's threat to take his grievance to the Board of Health when an over-officious young Ranger was slow in marking logs for a new bathroom."*

*No Life for a Lady," by Agnes Morley Cleaveland, Houghton Muffin Co.

Long-time career man Stanley Wilson, who retired in Phoenix, had worked in the Magdalena office of the Datil Forest as Deputy Supervisor in the early twenties, and has a fund of Morley stories.

Wilson recalled a case where the Forest Service Regional Office had written Morley a series of three letters asking for his side of reports from the Datil office that he was in trespass violation with a band of sheep.

"Ray had an interesting way of letting his mail pile up and then he'd read it all at once," Wilson said. "He came into the office one day when I happened to be Acting Supervisor."

"Wilson," Ray said, "I've got notices from the Regional Office to give my side of the three trespass cases you've reported on. What am I gonna tell 'em, Wilson?"

"Well, Ray, that's up to you," Wilson replied.

"I can tell 'em. . . ." and Ray went on with what Wilson described as a "string of stuff."

"Don't tell them that," Wilson told him, "because we can prove that it isn't true."

Wilson recalled that Ray then tried a different tack, but Wilson interrupted, "No don't tell them that either."

"Oh," Ray said, "I've got something. Did you know this Watson, the man that looks after my sheep is sick with stomach trouble and he's been in Albuquerque. They've been putting barium in him and takin' X-ray to see what's wrong with him. So my sheep were neglected while he was in there."

"Ray," Wilson said, "that's new material, that's something you can tell them."

"Let me borrow a stenographer, will you Wilson?"

Wilson said, "Sure," and Ray sat down and wrote three replies to the Regional Office, answering the three letters.

"He got out of all three of them, just like that," Wilson commented.

When Morley operated Navajo Lodge for travelers going through on U.S. 60, he gained wide fame for the tall tales that he told the travelers.

"I got in there one night with a nephew of mine," Wilson remembered. "Ray was there, and I thought, gee, this kid has a chance to hear something he'll remember all his life."

Wilson was talking to Ray, and he said, "Ray, I've been hearing some stories about you. Are they true?"

"Well, it depends on what you were hearing, Wilson. What'd you hear?"

"That story about you killing a lion by holding his head under snow water."

"Oh yes; yes, that's true," he said, "I was riding up in White Horse Canyon. There'd been an early snow, or a late snow—I'd have to figure out which time the fawns come. I saw a fawn behind a down log and I figured I'd get off my horse and sneak around until I was behind that log and then I'd make a flying leap over the log, catch this fawn and take it home for a pet. I went around a circuitous way, and I peeped over the log and I saw a tiny thing there, and I made a big jump over the log and unfortunately I came up with a full-grown mountain lion. Well, there was a pine tree between it and me, and I had it by the scruff of the neck with my left hand and it was around the tree and I had its tail in my right hand, and it kept comin' after me, and I kept backin' up, and my boot heels got hot and melted the snow, and pretty soon I got enough water so I held his head under and drowned it."

By the time Ray launched into his story there were nearly two dozen people in the lounge, and Wilson said they accepted the yarn without a quibble. In fact, one of them asked, "Is this the skin here, Mr. Morley?"

"No," he told them, straight-faced, "it's the one in the other room. But I'll tell you about this one. This one jumped on the running board of my car, and I killed it by sticking it in the eye with a hat pin."

Wilson remembers that he went on telling stories and finally told one "that I knew to be absolutely true."

"He said that in the early days he had to make a trip to Magdalena," Wilson related. "That was 34 miles away, and he decided he was going to make it in two hours. It had never been made in two hours before."

"Morley had in the car John Kerr, Assistant District Forester in the Grazing Division, and a couple other men.

"They started out," Wilson said, "and when they passed a teamster, Morley hollered at him they were going to set a record and get to Magdalena in two hours. About that time Morley wasn't watching where he was going, and he turned the car over. Nobody was hurt. The teamster came up and helped them to put it together again, and Morley turns around and says, 'We can still make it in two hours,' and he started again. Then, 'We got to the Continental Divide, 12 miles out of Magdalena, and we hit a rock that musta been fastened in the center of the earth. We turned over again and that time I thought I was dead. They couldn't hear me; they thought I must be dead, but I was crowded under the front seat of the car and couldn't do anything. When they rolled the car off of me I wasn't hurt but John Kerr had a broken shoulder.'"

According to Wilson that was true. "John Kerr did get a broken shoulder. He was always uneasy riding fast with people after that. When Morley finished his story, one of the Oklahomans in the room told him, 'Mr. Morley, that's one I don't believe.' So I said to Morley, 'Ray, that's a story I personally know to be absolutely true, and it's the only one you tell that anybody doubts.'"

Frederic Winn, who was Supervisor of the Coronado National Forest when he retired, spent a couple years as a Ranger in the Datil Forest, and was a close friend of Ray Morley's. Winn had first come to New Mexico as a cowboy-artist. He had attended Princeton, and had lost his hearing in an ice-boat accident on one of the lakes outside Madison, Wis.

Stanley Wilson tells this story about Ray Morley at the time Fred Winn was staying at his place:

"There was a young fellow that Ray met down at the Post Office. Lots of people came out here to the Southwest for their health in those days, and this young fellow asked Mr. Morley if he could give him a job. Ray said, 'Well, you come up to my place and you keep the woodbox filled and do odd jobs, and it'll be worth your board, and I'll pay you a little money. If you're worth anything, I'll take you on.' Well, he was in the negative category; he wasn't worth anything. So they arranged that they would pull a game on him. There was a fellow named Johnny Payne; they called him Bow-legs because he was bow-legged. I can't think of the other men. They arranged that they would stage a fight. Fred Winn was there but being deaf couldn't hear the plans. They took the bullets out of their cartridges to make them blanks when they got ready to go on this thing, and Johnny Payne brought his dog in the house and the other fellow took a kick at it. Johnny says, 'You can't kick my dog,'—and he pulled his gun. The boy started trying to get out the door; the other fellow grabbed him and held him so he couldn't get to the door. They exchanged shots and finally Ray Morley fell over on his back, apparently dead. Fred Winn had jumped up on something that put him so high up he had to stoop against the ceiling. He thought this was real, you see. He was looking down at what was going on. Ray Morley looked up and winked at him, and Fred was mad. He was really mad.

"They decided that this boy would probably go over to Mrs. Cleaveland's and she would be worried to hear that Ray was dead. Johnny says, 'Well, I'll saddle my horse and lope over there and tell her that this was a joke.' So he did, and as he was coming back he remembered that he had used all his cartridges. He got out his six-shooter and started to load it as he was going over a little bridge. This young fellow was hiding under that bridge. He came out and says, 'Please don't shoot me.'

Johnny says, 'Now look, you're in a tough situation, Ray Morley's dead and I know you didn't kill him, but that other fellow's gonna say you did, so the only thing I can think of for you to do is just get out of here.' So the boy left the area. Later on, Ray used to go back and ride in parades and things back East. One time he saw this young fellow and the fellow told him, 'Mr. Morley, you missed your calling. You should've been an actor!'"

One time when Morley had been gone from Datil for awhile, Fred Winn was in Baldwin's store and saw a new buckboard and team. He asked whose it was and was told Ray Morley had come home.

Morley had come home with a new wife, but they hadn't told Fred that, Wilson remembers.

"They told Fred, 'Ray's in such and such a room.' Fred went in and knocked on the door. Ray tried to tell Fred his wife was in there with him and he couldn't let him in. Fred couldn't hear him. So Fred went around to a window, and he pried the window open. There was a trunk there under the window and he came in on his hands and knees over this trunk. When he got in, there was Morley's wife, sitting up in bed, with a blanket wrapped around her and screaming bloody murder. Fred, of course, backed out. Being shy, it almost killed him."

Some of the stories involving Morley included as a participant Steve Garst, who was a Ranger of the Datil Forest for more than 20 years. Garst was a big man, weighed in the neighborhood of 250 pounds, and was the son of a retired Navy admiral. He was the kind of man who could get along with Ray Morley.

Steve Garst early discovered that Ray was running some loose cattle on the Forest that he had no permit for. Wilson related that Garst got hold of Ray and told him that he had found some trespass cattle on Morley's range.

"Why, gee, Steve, that's bad," Ray said. "We ought to get rid of them. Whose are they?"

Steve said, "Well, I just don't know. I haven't found out yet, but they're branded so-and-so."

They were Ray's, of course, and he just said, "Oh, heck. . . ."

When they opened the Black Canyon Refuge to hunting, Wilson related that Morley went down there with a wagon and came back with six deer over the limit.

"When he came up to the head of Railroad Canyon," Wilson said, officers met him and they took him over to Dub Evans, the JP. Dub fined him $50 for each extra deer—$300. Ray said, 'Now, Dub, and you fellows, now that's perfectly all right. I took a chance and I'm perfectly willin' to pay my money, but for God's sake, don't ever tell Steve Garst about this because I'll never hear the last of it.' Dub Evans said, 'Ray, who do you think tipped us off? It was Steve Garst!'"

Over in the Apache National Forest, the Rangers were holding a meeting* to discuss a variety of problems including trespass, reconnaisance, timber sales, and even wild horses.

*Rangers meeting, September 8-14, 1910, at Springerville, Ariz.

"A wild horse is a pest and ought to be gotten rid of," spoke up M. L. Nichols, Ranger on the Metcalf District.

"I don't know of any feasible way of catching wild horses," Ranger Chapin, of Murioso, told the group.

J. H. Sizer, of Eagle, didn't agree. "At least three or four Rangers ought to start out and gather up every horse they could find—and go it alone if they could not get any stockmen to go along with them."

Jim Reagan shook his head. "It would take three or four years to round them up."

It did, in fact, take many years to solve the wild horse problem.

Telling of wild horses on the Apache National Forest in the 1920's, Jesse Fears recalled that the Forest was overrun with "unpermitted horses," as he referred to them rather than as wild horses:

"I first notified these people and tried to get 'em to get rid of their horses, and they laughed at me. Said if they had trespass horses, why didn't I get 'em for trespass, and I said, 'I will when I get to it.' Then Roy Swapp and I threw in together and the first winter we gathered—before they knew it we had 'em gathered down on Campbell Blue—over 800 horses in one bunch. Then I actually gathered 2600 head of unpermitted horses on the Greer District. They were tallied and a record made of 'em before I killed a horse. We threw them out on the public domain. Loco weed got a lot of 'em."

Fears told of another bunch of horses he rounded up and advertised for sale when possible owners made no claim after 60 days.

"Nobody bid on 'em except Melvin Swapp," Fears said. "He bid on a mare that was unbranded. When nobody else would bid on them, I said, 'Well, I'll just keep 'em and see what I can do with 'em.' I turned them back out in the pasture. So when things quieted down I got a permittee and a fellow working for me and we went up there and rounded 'em up and we shot 'em.

"We left the best looking ones out there. Well, it was a month or two before they discovered those dead horses, and then the fat was in the fire. A lawyer got hold of it, and he agreed to prosecute me through the courts for $300 if they would put up the money and he'd be deputized. They dug up the money for him. The sheriff I knew well. I told him, 'Any time you get a warrant for me, just call me up. I'll come down. You won't need to come up and serve it.'

"So he called me, and I went down to St. Johns."

Fears told of the court routine and the delays due to attorneys' arguments, and the judge's final decision to give the opposing attorneys 10 days in which to submit briefs.

E. S. French, the Forest Service law officer, submitted his brief in 24 hours, since it had already been prepared.

"The funny thing was," Fears remembered, "they didn't have anybody there who could write shorthand. They could write a few words of the testimony, then they just put a lot of lines out there. French got hold of the clerk and said, "Don't you remember asking this and him saying that?" So the clerk put those words in afterwards—different things that weren't in the shorthand notes.

Fears recalls the case went on for quite awhile. There were letters back and forth about the prosecution briefs which were not filed or copies sent to French, and finally the Forest Service attorney demanded a speedy trial. So the judge set a date for the hearing—and found Fears guilty.

"He had the decision already written up," Fears related, "because he said there would be a few minutes recess, and we didn't get out of the courtroom until he called us back. He had it already typed up, and he read it. He said he couldn't see where Regulation T-12 of the Department of Agriculture had any effect in law. Therefore he would find me guilty and would fine me $1.00. Then French got up and said, 'Your honor, my client refuses to pay the $1.00 fine. What will be the alternative?' The judge turned to the sheriff and told him to levy on any property I had for that $1.00 fine. French immediately filed notice of an appeal to the State Supreme Court.

"After they had studied it, they sent it back and said that everyone knows that Federal laws are paramount to state laws. Therefore they had no right to arrest me when I was carrying out the instructions given me by the Secretary of Agriculture and they should throw out the charges against me and refund my bonds. It was a year before we got a release on the bonds."

The government attorneys next enjoined the county and state officials from interfering with the carrying out of Forest Service regulations and the case went to Federal court in Los Angeles and after a delay to the Federal Court in San Francisco, where a decision was handed down in favor of the Forest Service and helped to establish the precedent for disposing of unpermitted horses.

|

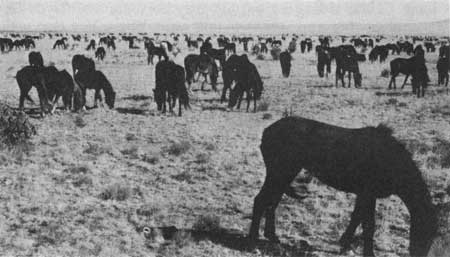

| In the early 1900's, bands of unpermitted horses multiplied unchecked on many western ranges and competed with domestic livestock for forage. |

Paul Roberts, talking one time about the wild horses on the Sitgreaves National Forest, said, "Well, we could never get rid of them. We'd impound them, and they would come and get them and take them home, and then in a little while they'd be back on the Forest."

"We rounded up some," he went on, "and we had some horses that you couldn't round up. We rounded up the east end of the Forest one time and we put these horses all in a pasture near Show Low. Then we put a guard on the pasture so they couldn't get them out of there while we went farther back and rounded them up.

"We went still farther east and rounded them up and brought them back. When we got back with this outfit from the east end of the Forest, we'd been gone about a couple of days. Well, by gosh, you'd of thought Coxie's army was camped on that flat. There were just bed rolls all over the place. We had only one corral and we had to rope them out of there for those who were claiming them.

"Old Captain Hale was helping. He was an old cow hand just off the Forest. I guess Cap musta been about 70 at that time. Well, by golly, he and I roped horses out of that corral all day long. I was riding a great big gray horse, one of Clyde Shumway's—he was big and stout to rope on. You know that was the only time in my life I ever pulled the cinch rings oblong on a saddle. But that night my cinch rings were just pulled out oblong—roping those horses and dragging them out of there."

Another time, Roberts recalled, they ran into a problem because of shooting wild horses. "Those fellows that owned horses would go out in the spring when the colts were weak, and they'd rope and branded them. Then they might never see those horses again. In shooting horses, Dolph Slosser (then Ranger at Pinedale) and his assistant, Bill Porter, shot a couple of branded horses. The outfit that owned them beat up on Porter and put him in the hospital for a while. They tried to get old Dolph, but someway they didn't do it. I was up in Denver and I got a wire to 'come back home quick.' Slosser and Porter had been arrested.

"My wife met me at the train and took me up to Taylor. They guarded me going into the JP's office there . . . anyway, they bound these two fellows over to the Superior Court. In the meantime, we went down to Phoenix and applied for an injunction in Federal Court, enjoining the county from interfering with us in shooting these branded horses. The case didn't look very good for us for awhile either.

"Well, that day we were eating breakfast in the cafe and in came all these fellows that were prosecuting the case. They all filed by me and they all spoke to me, 'Hello, Paul,' and smiled. They figured they had an open-and-shut case. Old Dooley McCauley was county attorney. The sheriff (Navajo County) was sitting beside me, and he says, 'Paul, I think we're gonna lose this case.' And he was the one that was bringing the case against us. He wanted to be enjoined. He thought the Forest Service was going to lose. Anyway the thing went on for quite a while. The judge called a recess and went back in his chambers and came out. He was only gone for about five minutes. He came back and he gave us an injunction.

"That night I was sitting in the same cafe and these guys all came in to eat supper, and there wasn't a damn one of them that would speak to me. But we won that case.

"I don't know whether this is true or not, but I think it was French who told me that the judge looked up the definition of a wild horse in the dictionary and it said that any horse on the range that had the appearance of being wild was a wild horse.

"That was the case that cracked the Secretary's shooting order, wild horse shooting order. I don't think there was ever much difficulty about it afterwards. We removed horses on the Chevelon District that were wearing brands that hadn't been run for 20 years. It's a wonder that there was any range left. That took a big load off of the range."

The injunction referred to by Paul Roberts was issued by Judge F. C. Jacobs in Federal Court in Phoenix on April 9, 1931, in the case of the U. S. vs. C. D. McCauley, county attorney, and L. D. Divelbess, the sheriff of Navajo County.

In a memorandum to Forest Officers, Quincy Randles, then Acting Regional Forester, pointed out that the case was of much importance to the Forest Service in carrying out its policy of ridding the range of wild horses.

The injunction authorized the Forest Service to "dispose of, by shooting if necessary, any wild horse of unknown ownership, as herein defined, whether branded or not, found in trespass on the National Forest running at large on the Forest after said range has been closed by the Secretary of Agriculture to the grazing of wild horses of unknown ownership as herein described and reasonable notice has been given thereof."

Commenting on the injunction, Quincy Randles wrote the Rangers that "It is realized that where wild and gentle horses are mixed on the same range, it is rather difficult to distinguish the gentle horses from the wild ones, consequently a gentle horse may be killed accidentally, in which case the Service would be criticized, but if reasonable diligence is used to determine whether the horse is wild or gentle and notice of the time set for shooting the wild horses is given to the local stockmen, it is felt the closing order procedure will be supported by the Federal courts and by public sentiment."

Most of the old-time Rangers can recount unique experiences in trying to rid their districts of wild horses. Bob Ground, who was a Ranger on the Carson and Santa Fe Forests for 34 years, told of men coming into the Jicarilla District of the Carson National Forest to try to round up some of the wild horses.

"They'd run and kill a good horse to get a poor one," is the way Ground put it. "A lot of people seemed to get a lot of sport out of that—runnin' wild horses."

By the time Stanley Wilson was appointed Supervisor of the Carson National Forest in 1924, the wild horse problem had become particularly vexing.

"In 1925," Wilson recalled, "we issued notices that the trespass horses on the Canjilon District of the Carson would be rounded up, and that permittees could redeem their stock caught in the roundup by paying the cost per head of the roundup, and the rest of the stock would be sold at auction. We rounded up 1200 head of wild horses. Very peculiarly, when you looked at them in the bunch it looked like there were some pretty good horses, but actually when you got among 'em, they were all small, so one that was a little bigger kind of stood out. Well, I figured that the cost per head was $3, so we let people redeem their stock at $3 a head. Some were redeemed, but not a great many. Then we started letting people go in and pick out some they wanted and pay $3. Well, that wasn't good because we were creaming our bunch. So then we offered to sell the whole outfit at auction, and that didn't work. We had no bidders. Then we decided we could sell them by private contract. I think the first sale we made—there were three young fellows from Colorado who had worked on some of the Forests on fires up there and had some government checks. They said they were willing to spend them on horses if we didn't charge too much. We asked them how many they wanted, and, as I remember, they said they would take a couple of hundred head. We said we'd sell them for 50c apiece and throw in the colts. Also we would let them have a 5% cut on horses they didn't want. So we started counting out their horses. We came to one with a hip knocked down and the fellows said, 'Well, we don't want that one.'

"L. L. Feight, who was the District Ranger, said, 'That's all right; take that one and we'll give you an extra one for him.' We let them take whatever it was, a couple hundred head I think, and then we gave them additionally for the ones they complained of. What we wanted to do was get rid of horses. Well, we sold some to the local people. Frank Andrews later griped about it because he said that one fellow took the horses from our Forest and came down and turned them loose on the Santa Fe, where he was Supervisor.

"Those three boys from Colorado kind of got cold feet on their deal so they started selling these horses to people who came around. So one of them said, 'Well, I'll tell you, we'll sell enough horses to get our money back and we'll turn the rest of them loose.'

"Ranger Locke Feight happens to be a very ingenious fellow. It was a little difficult branding all those horses. Locke made up some stamp branding irons so we could just hit them once instead of doing it the hard way. We had a chute and we put them in there and we branded them. When we were pretty near through, I said to one of these fellows who was figuring on turning these horses loose, 'You know, when we have a lot of horses belonging to many owners, it's very difficult for us to do anything, because you can't make 50 trespass cases against 50 owners for $3 head apiece. But, when we've got one owner that has an appreciable number of horses, why we can go to court and make it stick.'

"'Furthermore,' I said, 'if you're worrying about the difficulty of driving your horses back into Colorado, we'll lend you a couple of Rangers to help you get over across the line.' So we actually did get rid of them 1200 horses OK."

Perl Charles, who also served on the Carson, remembers that when he was a Ranger on the Jemez River District, he started rounding up horses in the early 30's after the Forest boundaries were fenced.

"We took over 1500 head of horses off that one District," he said.

When the Rangers started removing horses on the Carson, some cattlemen began killing wild horses on their own. "Of course, we got blamed for it," Perl Charles said. "We had some pretty close shaves with those fellows. There was nothing we could do but try to talk them out of it. Personally, I had a lot of experience with that. I couldn't run very fast, and I wasn't big enough to fight, so I had to talk them out of it."

Once when Charles was rounding up a bunch of horses on the Rock Creek area of the Carson, he found a local rancher, a fellow named Manuel, in the horse corral. Manuel had once been in the penitentiary for killing a man.

"What are you doing in there?" Charles demanded.

"Gonna get my horses."

"You can't take them," Charles warned him.

"I am."

The Ranger then walked into the corral, with a dozen of Manuel's compadres standing around the corral, some of them armed with weapons of one sort or another. Charles recalls that he must have stood there in the corral for as long as two hours, just arguing with Manuel.

"There was just nothing for me to do but talk them out of it," he said.

Finally, to settle the matter, he told Manuel: "You can take your horses, the horses you want. They'll be $3.00 apiece."

"I don't have three dollars."

"O.K. I'll give you a job and we can work it out."

And that's the way it was settled. "I gave him a job in camp," Charles said. "He didn't do anything but stayed around long enough to work it out."

Another time Charles and Ranger Joe Rodriguez were rounding up horses in the San Pedro Park district and then the Baca Location for a total of about 400 horses.

"Fellows had been coming up there and buying those horses for a dollar or two a head," Charles said. "They didn't have much interest in them. They'd get loose and come back again. So this time I told them we'd start the sale at $10. If they were interested enough in them to pay $10, why they could buy them individually. Otherwise we'd sell them in a bunch and take them off the Forest. They told me I couldn't do that. Then they called the old man, Frank Andrews (the Supervisor)."

The conversation went something like this:

"This fellow down here, he's not doing this according to law. We're pretty mad."

"All right. All right," Supervisor Andrews said. "I'll be out."

"You'd better get here pretty quick."

"What time is he going to sell them?" Andrews asked.

"About 9 o'clock in the morning."

Nine o'clock came. No Supervisor. The sale started. Ten o'clock. Still no Supervisor. The sale neared its end.

Finally Andrews arrived.

"He was just as apologetic as he could be," Charles said. "He said he had a breakdown—car trouble or got stuck or something. I wondered if he ever intended to be there at 9 o'clock. These fellows who had called him told him the sale was illegal. The old man told them, 'Well, it's done now. There's nothing we can do about it.'

"Years later he told me he hadn't been too anxious to get there too early!"

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tucker-fitzpatrick/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2008