|

History of the Fremont National Forest

|

|

Chapter 2

The Early Years

PERSONNEL 1906 — 1910

| Forest Inspector | Martin L. Erickson (1907) |

| Forest Supervisor | Guy M. Ingram (1907-1910) Gilbert O. Brown (1910-1931) |

| Deputy Supervisor | Gilbert D. Brown (1908-10) |

| Staff Assistant | Richard F. Hammatt (1907) |

| Clerks | Ollie E. Cannon (1907) Vada J. Bonham (1907-1909) Murrie Johnson (1909-1917) Millie E. Gibbons (1909-10) Nell Simpson (1909) Daniel F. Brennan (1910-1917) Ida D. Estes (1910) |

District Rangers | |

| Warner | Mark E. Musgrave (1907-1909) Pearl V. Ingram (1910-1934) |

| Goose Lake1 | Wm. C. Neff (1907) |

| Paisley2 | Jason S. Eider (1908-1920) |

| Silver Lake | Gilbert D. Brown (1907) Nelson J. Billings (1908-1909) Gaines H. Looney (1910-1913) |

| Dog Lake | Earl Abbott (guard) (1908) Sherman A. Brown (1909) Earl Abbott (1910-1912) |

| Thomas Creek | Scott Leavitt (1908-1909) Earl Abbott (1909) Reginald A. Bradley (1910-1913) |

| Summer Lake | Clinton W. Combs (1910-1911) |

District Ranger Personnel

Nelson Jay Billings (Silver Lake)

Bill Blair (Paisley)

James Brady (Paisley, Silver Lake)

Theodore F. Cadle (Goose Lake, Paisley)

Lynn Cronemille (Thomas Creek)

Lester E. Elder (Paisley)

Carl M. Ewing (Silver Lake, Dog Lake)

Lawrence Frizzell (Silver Lake)

Thomas H. Griggs (Silver Lake)

W. F. Grube (Silver Lake)

W. R. Hammersley (Dog Lake)

R. B. Jackson (Silver Lake)

Thomas Clifford Johnson (Silver Lake, Paisley)

Scott Leavitt (Dog Lake, Thomas Creek)

Elzie Linville (Warner)

Gaines H. Looney (Silver Lake, Paisley)

Win. C. Neff (Warner)

Martin O'Brien (Silver Lake)

W. J. Patterson (Silver Lake)

Frank D. Petit (Silver Lake)

C. W. Reed (Silver Lake)

Dexter B. Reynolds

C. E. Thanbrue

W. H. Tucker (Paisley)

Charles W. Weyburn (Silver Lake)

Hunters

Andrew Canterberry

William R. Hammersley

Personnel Sketches

M. L. Erickson. Although the Goose Lake and Fremont Forest Reserves were established August 21 and September 17, 1906, they were not put under administration until February 1, 1907. Martin L. Erickson, inspector, was placed in charge on this date, and remained in this position until May 31, 1907. The following news release covers his arrival:

M. L. Erickson, forest reserve inspector, arrived in Lakeview Tuesday from Portland to take charge of the Goose Lake Forest Reserve. The reserve is now under administration, and the general rules of the service will be applied. Parties desiring to graze stock on the reserve will be required to obtain a permit. He wishes to receive applications as soon as possible. The cutting of timber and special privileges will be regulated by him and general information promulgated. A number of rangers and guards will be put on shortly. Mr. Erickson has established offices over the First National Bank. (Lake County Examiner, February 4, 1907)

Guy M. Ingram. Guy M. Ingram was born July 25, 1881, on his father's farm on Deer Creek in Douglas County near Roseburg. He was educated in the local public schools and was first employed by the Interior Department as ranger on the Cascade Forest Reserve (south), now part of the Umpqua National Forest. When the transfer to the Department of Agriculture was made in 1905, he became ranger for the Forest Service at $60 per month. Being an efficient ranger he was rapidly promoted until on January 1, 1907, he was receiving $1,200 per annum. He had a very pleasing personality. ("Timberlines", June, 1961)

On February 11, 1907, Guy M. Ingram was transferred from the Cascade South Reserve with headquarters in Roseburg to the Fremont and Goose Lake Forests with headquarters at Lakeview, Oregon. On June 1, 1907, his title was changed from forest ranger to forest supervisor.

The trip from Roseburg to Lakeview at that time required three days and is described in Mr. Ingram's diary as follows:

Left Roseburg evening of February 11 on train for Thrall, California. February 12 left Thrall, California, 9:00 a.m. via railroad to Pokegama. Then via Klamath Lake Navigation Company Stage Line to Rapid City, thence via Klamath Lake Navigation Company Boat Line to Klamath Falls. Arrived Klamath Falls 10:00 p.m., where remained over night. February 13 left Klamath Falls 7:00 a.m. on stage and rode until 11:45 p.m. Stage made no overnight stop. Changed horses and started out again at 12:15 a.m. February 14 arrived Lakeview 11:00 a.m.

When Guy M. Ingram became supervisor of the Goose Lake and Fremont Forests June 1, 1907, he found an undeveloped area of 1,865,720 acres, extending north from the Oregon state line over 125 miles. Since everything was new and few policies were established, this was a difficult position. There was much work to be done, few employees to do it, and very little money.

Since the public domain had been open and free to grazing for many years, the numbers of livestock steadily increased until the ranges became overstocked and overgrazed. Aside from the range problems, there were hundreds of miles of forest boundaries to run and post; private lands to locate; and roads, telephone lines, and ranger stations to build.

Supervisor Ingram resigned September 12, 1910, after serving slightly over three years. He went to California and successfully engaged in the real estate and insurance business. He died at Forestville, California, November 11, 1958. His brother, Pearl V. Ingram, served on the Fremont as guard and ranger for thirty years.

Gilbert D. Brown. Gilbert D. Brown was born in Dixon, California, on April 4, 1878. In 1892 his parents moved to Crystal in Klamath County. When he was sixteen, he went back to California to attend school at Vacaville. He worked for room and board, completed the eighth grade, and attended normal school and business college. He returned to Oregon, took the teachers examination, and taught in country schools in Klamath and Lake counties. In 1905 he took the forest ranger's examination in Grants Pass, which was quite different from later ones:

The examination required three days: the first day was devoted to rifle and revolver practice, packing a horse, throwing a diamond hitch, squaw hitch, etc.; then running the horse around the lot to see if the pack would stay on; the second day was taken up in cruising a 40-acres tract of timber, cutting down a tree with an axe and piling the brush. The tree assigned to me was a pine about one and one-half feet in diameter, partially dead; some job! On the third day we took written tests in arithmetic, spelling, etc. On account of my experience in the woods, handling horses and pack outfits at home, combined with my hunting and shooting experiences, I managed to complete the examination with a fair rating. On account of teaching during the winter of 1905, I wasn't able to accept an appointment until 1906 after my school closed in June.

His first forestry work was under Supervisor S. C. Bartrum of the Interior Department on the Cascade South Reserve, with headquarters at Roseburg. He spent the summer of 1906 near Portland, the Clackamas River, and Mount Jefferson fighting fires, building fence, and doing other forest work. Learning that the Fremont Reserve was to be put under administration, he applied for a transfer there and was assigned to the Silver Lake District, April 1, 1907, as ranger.

Upon arriving at Silver Lake April 1, 1907, I found a vast area of forest without telephone lines, roads, or trails, and transportation was entirely by saddle horse and pack outfit. The work to be done consisted of running and posting forest boundary lines, reporting on June 11 claims (most of which were fraudulent and had been filed in order to get timber and were consequently rejected), besides forest improvements, grazing trespasses, issuing crossing permits for livestock, free use permits for timber, etc.

In December, 1907, Brown was transferred to the supervisor's office in Lakeview as acting deputy supervisor. He traveled to Lakeview on horseback. After the resignation of Supervisor Guy M. Ingram, September 12, 1910, Gilbert D. Brown was promoted to forest supervisor on October 8. After serving twenty-four years on the Fremont, twenty-one and one-half years of which he was supervisor — the longest term of any Fremont supervisor — he was transferred to the position of supervisor on the Wenatchee National Forest.

Reginald A. Bradley. Reginald A. Bradley was born October 25, 1867, near the Thames River about twelve miles from London. His father, Robert, was a lawyer, and his grandfather, Edward, was a professional artist. Bradley attended both the English elementary schools and the South Kensington School of Art, then the largest art school in London.

My real desire at that time was for adventure. I read all the wild west books I could get my hands on. Finally in October of 1888 I came to New York City on the steamship Lydian Monarch.

He stayed with friends in the east for several months, then one day a friend wrote that he had a job for him in New Mexico. He went to work for a cattle company as a day horse herder at $15 a month.

I went on one trail drive while working there. We trailed thirteen hundred steers to Deming, New Mexico, about two hundred miles away. One night we corralled the steers at Florida, a railroad siding, and discovered the corral was made of rotten ties. We discovered this after the cattle broke out and had to be rounded up again.

Bradley never used the word "cowboy." The word he used was "buckaroo."

All the buckaroos wore guns in those days. I had a .44 Colt and rifle that took the same ammunition. I also had a .45 I bought in New York.

You know, we never wore cleanly washed pants in those days, like you see them wear now. If a man wore clean pants or bib overalls, he wasn't a buckaroo but a farmer. We bought our trousers, took them out behind the barn and kicked them around until they were properly dirty and then wore them till they had holes in them. We never washed them. A man wasn't a buckaroo if he did that.

My family bought me a complete outfitting of clothes before I left England. One item they figured I couldn't get along without was a formal tuxedo. I never got around to wearing the darned thing. Sold it to a waiter in Deming in 1889 for $15.

Being out of a job in mid-1889, he traveled by railroad and freight wagon to Fort Bowie, Arizona Territory, and enlisted as a private in Troop C of the 4th Cavalry on November 12, 1889. In May, 1890, Troop C had an encounter with hostile Apache Indians, who had killed four travelers, including a doctor. One of the cavalry soldiers was wounded and one of the horses killed. They didn't kill any of the Indians. The soldiers chased the Indians about twenty miles over the border into Mexico before turning back. However, they couldn't put in their report that they had crossed the border.

The army rations in those days were quite different from those of today. They were allowed one and one-quarter pounds of fresh meat a day, or three pounds of rice a month; three cans of tomatoes and three pounds of sugar a month. They had to prepare their own meals. Whenever possible the soldiers would raise small gardens, or even pigs to sell, with the money going to the enlisted men's mess for delicacies. They were furnished no eggs, milk, or butter.

In June 1890, the 4th Cavalry was sent to Fort Walla Walla, Washington. That winter they were ready to leave for South Dakota to fight the Sioux. Then word came of the flight at Wounded Knee, which took care of the Sioux trouble. At Walla Walla, Bradley became good enough with the 45/70 rifle to go to Omaha and compete in a service match. Unfortunately for his scores, it had been a long, dry trip to Nebraska, and in those days Omaha had a fair number of saloons and well, as Mr. Bradley said,

I wasn't drunk, mind you, but it had been a long time since I had been able to drink any beer. I probably put more holes in my competition's targets than in my own, but I still managed to place sixteenth out of a field of twenty.

The 4th then served at Fort Bidwell, California, where Bradley received his final rank as sergeant. He was the last soldier to leave this fort when the army abandoned it in 1893. The 4th was then stationed at the Presidio in San Francisco where Bradley was discharged November 24, 1894. He returned to Fort Bidwell and married Miss Mary Hilderbrand, whom he had first met at a dance there.

For several years Bradley homesteaded and ranched in northern California and Oregon. In 1909 he was a rancher on McDowell Creek where he ran 100 head of cattle and also owned sheep.

In the fall of 1909 he took the ranger's examination and received an appointment as ranger on the Thomas Creek District. Because of his ranching background, he understood the problems of the stockmen and got along well with the grazing permittees. He served on the Thomas Creek and Dog Lake districts until April 1, 1914, when he was promoted and brought into the supervisor's office as deputy supervisor.

He bought his Davis Creek ranch in the fall of 1917, and for two years had a grazing permit for 175 head of cattle on the Modoc National Forest. Supervisor Durbin told him it was causing criticism and that he would either have to quit the Forest Service or lose his grazing permit. Due to the high prices received for cattle at this time and the low salaries received in the Forest Service, Mr. Bradley resigned March 31, 1920, as deputy supervisor of the Fremont and moved to his ranch.

He retired in 1937, and at a later date he went to live with his daughter. He resumed the art work started as a young man and won first prizes in the advanced category at the county fair. He has exhibited his paintings and sold many of his landscapes. One of his paintings is hung in the Hall of Congress in Washington, D. C.

On his 100th birthday, Bradley was feted by a military review held in his honor at the Presidio of San Francisco, where he was awarded the honorary rank of Sergeant Major and, quite belatedly, his Indian Wars Campaign Medal.

Sergeant Bradley was the last survivor of the American Indian Wars. He died February 5, 1971, at the age of 103. His internment at the military cemetery of the Presidio was at the request of the army and required presidential approval.

In coming to America, he was seeking adventure, and he found it in his long and colorful life as a buckaroo, a cavalry trooper, a forest ranger, a rancher, and an artist. (The Modoc Record)

Scott Leavitt. Scott Leavitt was born at Elk Rapids, Michigan, on July 16, 1879. During the war with Spain he served in Cuba with Co. L. 33rd Michigan Volunteers, the company being composed exclusively of sons of Civil War veterans. Upon his discharge from the service, he entered the University of Michigan, but before completing his course went to Oregon.

Scott Leavitt took the forest ranger examination at Lakeview in the spring of 1907. He worked during July without appointment with Guard Bill Hammersly in the Dog Lake area.

His first assignment under appointment was on the Thomas Creek District (Chewaucan area), where with his wife and two babies he lived in a cabin obtained from a stockman. The cowman's brand was 00 on the side, and he moved out stored salt so the Leavitts could move in. During the summer, Mr. Leavitt patrolled, posted boundary, cooperated with the stockmen, and in the fall moved back to Lakeview.

In the spring of 1908 was put in charge of a road crew building the beginning of the first road to Cottonwood Meadow. We lived in a tent. When the road money ran out, took the family back to Lakeview, kept the tent and spent much of the time with saddle and pack-horse. Stockmen were getting located and boundaries agreed upon, and the work became varied and interesting. No timber sales as yet but fire patrol was constant.

Was in the Lakeview office again that winter, and diphtheria came to Lakeview. Far from a railroad, there was no serum, only old-time methods, and we lost our little four-and-a-half year old girl. Our son, Roswell, then two, recovered and became supervisor of the Lolo National Forest in Montana.

Assigned to the west side district in the spring of 1909, I hardly got started there until, effective April 21, 1909, I was transferred to the Superior National Forest in Minnesota as an experienced ranger to help put that forest under administration. That ended my service on the Fremont. I did not see Lakeview again until 1947 when I visited the Rotary Club in my capacity of Rotary District Governor. (Scott Leavitt, October 8, 1962)

In 1912 Leavitt became supervisor of the Lewis and Clark Forest in Montana, and in 1913 was transferred to the Jefferson Forest at Great Falls. In 1918 he resigned from the Forest Service, and after being denied a place with the fighting forces on technical physical grounds, he was Federal-State Director of War Emergency Employment Service and of the Public Service Reserve.

In Montana, Mr. Leavitt was credited with standing higher in the councils of the Republican party nationally than any other product of the state in a decade. He was elected to the House of Representatives from Montana in 1922 and served five terms until 1932. As far as we know, he is the only ex-Fremonter who served in Congress.

He was reinstated in the Forest Service in 1935 at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and retired as assistant district forester in charge of Information and Education June 30, 1942. He and his wife returned to Newberg. He died in 1966.

Nelson J. Billings. Nelson J. Billings was born January 26, 1880, in Fennville, Michigan. He worked for the Park Service in Montana before coming to Silver Lake as guard in 1907. He was promoted to forest ranger later that year.

In 1910 he was transferred to the supervisor's office as grazing assistant. Having a thorough knowledge of the livestock business, he managed the forest grazing problems with a minimum of friction and discord.

In 1913 he was transferred to the Wallowa National Forest as assistant supervisor and in 1920 promoted to supervisor. He remained on the Wallowa for seventeen years until he retired for disability in 1930. The family then moved to Salem. He died February 27, 1942.

Many campfire stories can be recounted of the early days and the role played by Jay Billings. As a partner "on the trail," few could excel him for jovial comradeship.

Mark E. Musgrave. Mark E. Musgrave was the first person to be in charge of the Warner Ranger District. He assisted Inspector Erickson in the first work on boundary surveys in the southern part of the forest and helped fence the "Dog Leg"3 ranger station site. He helped issue the first grazing permits and worked on claims cases. He wrote, "Many things of interest happened on the Fremont Forest in those early days. Stockmen refused to take out permits and even threatened the lives of forest officials. However, no blood was shed."

Musgrave transferred to the district office in 1909 as grazing assistant. He was forester for the City of Portland from 1912 to 1915. He worked for the Biological Survey and was assistant director of the Soil Conservation Service in Washington, D. C., when he retired in 1942.

William C. Neff. William Neff entered the service as a guard on the old Cascade Forest in 1906. He received an appointment as assistant ranger in 1907 on the Goose Lake Forest, at that time the area from the state line north to Paisley. Thus he was one of the earliest arrivals in this area. He worked on boundaries and ranger station buildings, issued grazing permits, and did other ranger work.

He transferred to the Crater Forest in 1909. Former Supervisor Carl B. Neal in the "Northwest Forest Service News" of March, 1953, tells of a letter Neff wrote to the supervisor of the Crater. Neff said it had been necessary to put snowshoes on his children to keep them from falling through the cracks in the floor of the ranger station dwelling. Mr. Neff passed away in March, 1953, at the age of 86.

Jason S. Elder. Jason Elder was born March 17, 1871, on the Elder Donation Claim on the Calipooia River near Shedd, Linn County, Oregon. He died in Portland January 4, 1936. Before coming to Paisley, he attended school in Prineville, where he was an eye witness to some of the shootings and hangings in the range wars. He came to Paisley September 30, 1902, and received an appointment as forest guard in charge of the district in April 1907. His first work was running forest boundary lines in open hills with a small pocket compass and proclamation map, his only equipment. In 1908 he received an appointment as deputy forest ranger.

Elder Creek and Elder ranger station were named for Elder, who had an important part in the administration of the Paisley District, including construction of the early improvements. Fish were plentiful in Dairy, Elder, and Bear creeks and in the Chewaucan River. It was common to catch fifteen or twenty in an hour. Deer were plentiful.

Pearl V. Ingram. Pearl V. Ingram was born in Roseburg October 30, 1878. From 1904 to 1909 he worked for the O.W.R. and N. Railroad between Huntington and Pendleton. His brother, Guy M. Ingram, persuaded him to come to Lakeview. The trip took three days — to Shaniko by railroad and then on the stage via Prineville and Bend. The potatoes and other crops along the way had been killed by frost. He started his work on the Fremont on July 22, 1909. He took the ranger examination that fall and received a ranger appointment May 1, 1910. In the winter of 1909-1910, he and several others from the Fremont — Brown, Billings, Looney, and Musgrave — attended a short course in forestry at the University of Washington. In the early days the main fire fighting crew consisted of Ingram, Al Cheney (fireman), and Norman White. On one occasion, lightning started thirty-two fires. That day the fires almost got ahead of the three-man crew. ("Six-Twenty-Six")

Pearl V. Ingram served longer on the Fremont than any other forest officer — thirty years. His pleasant and cheerful disposition was typified by the following poem read at the Ingrams' retirement dinner July 11, 1939:

He dropped into my office, with a grin upon his face,

He talked about the weather and the college football race,

He asked about the family and told the latest joke,

But he never mentioned anyone who's suddenly gone broke.He talked of books and pictures and the plays he's been to see,

A clever quip his boy had made, he passed along to me.

He praised the suit of clothes I wore, and asked me what it cost,

But he never said a word about the money he had lost.He was with me twenty minutes, chuckling gaily while he stayed,

O'er the memory of some silly little blunder he had made.

He reminded me that tulips must be planted in the fall,

But calamity and tragedy, he mentioned not at all.I thought it rather curious, when he had come and gone,

He must have had some tales of woe, but didn't pass them on.

For nowadays it seems to me, that every man I meet,

Has something new in misery, and moaning, to repeat.And as I write these lines for him who had his share of woe,

But still could talk of other things, and let his troubles go.

I was happier for his visit — in a world that's sick with doubt,

'Twas good to meet a man who wasn't spreading gloom about.

Norman J. Jacobson. Norman Jacobson was born June 1, 1887, in Wasco County, Minnesota, and attended high school in Port Washington, Wisconsin. He received a B. S. degree in forestry from the University of Minnesota.

He was appointed forest assistant on the Fremont July 12, 1910. He had charge of timber sales, free use, and technical forest work. In the fall of 1910, he planted 150 acres to seed. He made an extensive reconnaissance of the Fremont in 1911 and 1912, and in 1913 made another reconnaissance of part of the Ochoco, returning to the Fremont in December 1913. He was energetic and efficient in his work. His statement on leaving the Fremont was "Fremont is a fine forest. Real folks to work with and for; progressive and happy days!"

In 1914 he was promoted to forest examiner and transferred to the district office in Portland. Because of his executive ability, keen insight into Forest Service problems, and faculty of dealing with the public in a tactful and successful manner, he was assigned to the work of inspection of the cooperation between the Forest Service and the State Forester under the Weeks law. In 1917, Jacobson was promoted and transferred to Bend as forest supervisor.

In July, 1920, Supervisor Jacobson wrote to the regional forester to confirm his verbal application for a month's leave during September to accompany Irvin S. Cobb on some hunting trips — to the Warner Valley adjacent to the Fremont for antelope and ducks and to the Cascades for bear and cougar. Mr. Cobb planned to stay thirty-five days in Oregon hunting and camping out. It was planned to make a moving picture, and Cobb would write several stories for the Saturday Evening Post, giving the Forest Service much valuable publicity. In addition to Messrs. Cobb and Jacobson, others who planned to go on the trip were Bozeman Bulger, A. Whisnant of the Bend press, and Stanley J. Jewett of the Biological Survey. Mr. Jewett had been instructed by his office to go all out to help bag a cougar. Supervisor Jacobson had discussed the proposed trip with the district office over a year before and was given encouragement to participate because of the benefit to the Forest Service.

However, Regional Forester George H. Cecil would not grant Jacobson leave to make the trip during the fire season. He stated that there was a rule that no leave could be granted during the fire season and that no matter what the benefits were, he could make no exception.

Because Jacobson had made extensive arrangements for the trip, had promised to accompany Cobb and Jewett, and the people in the Bend community had become especially interested in making a success of it, he felt he could not gracefully back out. He felt that to cancel the trip would hurt the Forest Service more than it would himself personally, so, for the good of the Forest Supervisor, he resigned August 15, 1920.

Mr. Jacobson accompanied Mr. Cobb on the trip during which the movie entitled "Hunting the Big Silence" was made. It depicted the large humorist's outing on the east slope of the Cascade Mountains and showed in all its magnificence the grand scenery of the central part of the state, all the way from the Columbia River to Medford. Crater Lake came in for one whole reel out of the five, and two sections were devoted to Mount Hood.

The Forest Officer

The Use Book. In 1906 all forest officers received a nice, new Use Book, which contained all the rules and regulations necessary to properly administer the forest reserves. This little book was seven by four inches and contained 139 pages, including the index. From this little volume, which contained all the rules necessary to obtain the results expected, have sprung forth the forty-odd handbooks and manuals, which many of us have not had time to read, much less to find out what we want when we want it. Page 71 of the Use Book says in part:

While the Government is anxious to prevent and fight fires, only a limited amount of money can be devoted to this purpose. Experience has proven that usually a reasonable effort only is justified, and that a fire which cannot be controlled by from twenty to forty men will run away from 100 or even more men, since the heat and smoke in such cases make a direct fight impossible. Extravagant expenditures will not be tolerated.

Page 74 lists the field and office equipment for rangers and guards when, in the opinion of the supervisor, it is needed:

Marking hatchet, log, rule, ten (7' X 9'), pocket compass, badge, stationery.

Of course for general reserve work, the following tools are permissible: ax, shovel, saw, hammer. The supervisor would send his requisitions for equipment to Washington, D. C., to be approved there, and many articles were shipped from there — no big hurry. Page 86 says:

Each supervisor is required to keep at his own expense one or more saddle horses, to be used under saddle or to a vehicle for his transportation, and is allowed actual and necessary traveling expenses only when the urgency of the case requires some other means of transportation.

How times have changed. (Albert Baker, Umatilla National Forest, "Six-Twenty-Six," May, 1941)

The "Adviser". In closing the first edition of the "Adviser", the editor feels it to be not inappropriate to say a word regarding the position that we as forest officers should occupy in relation to the forest users and members of the different communities tributary to the Fremont.

Participation in the government under which they dwell is one of the traditional rights of the English speaking people, and it is a tradition to which all of us cling most jealously indeed. It is a part of our political creed which must be taken into account. Again, we must consider carefully the circumstances surrounding the early settlement of the locality in which we are laboring. The wide freedom of unrestricted range, the sparse settlement, the continual facing of severe exigencies has left its ineffaceable imprint upon the natures of the hardy men and women who were the pioneers of the region. It is impossible for a forest officer to deal successfully with these people without understanding and considering these things.

Do not understand that your dealings with users should be vacillating or that we should turn from the way of duty in any respect. Rather must we remember that the Forest Service is in a formative period, and that it is incumbent upon us to be intelligent ambassadors of the New Idea, firm in our allegiance to our policy, but doing our work in such a way as will eventually make of every user a staunch advocate.

There will be cases in which the steady hand of the government's authority must be used, but let us not forget that he will have rendered an immeasurable service to his country who has aided in making of the people loyal believers in and preachers of our policy. (Scott Leavitt, "Fremont Adviser," April, 1909)4

FIRE MANAGEMENT

Fire Report 1910

Of the twenty-three fires occurring this season, nine were caused by lightning and fourteen by man. The largest was the Sears Flat fire.

On May 16, 1910, a fire was started by W. S. Dennis to burn brush on his homestead at Fremont, Oregon. The fire escaped from Mr. Dennis' land in Section 4, T.26S., R.13E., W.M., and burned on to the national forest. In addition to burning off forty-five acres of his claim, the fire covered about 456 acres of national forest in Sections 5,6,8, and 9 in T.26S., R.13E. It destroyed about 30,000 feet of green timber worth $2.50 per thousand or $240, ninety-four acres of a good stand of young trees, and 120 acres of bunchgrass range on the forest.

Trespass report was made by Assistant Ranger Carl Ewing, who was at Silver Lake. The trespass case against Mr. Dennis was tried before the Grand Jury in Portland on March 21, 1911. He pleaded guilty and was fined $25. The case was given publicity as a warning to homesteaders and others.

Mr. Dennis' attitude was that the fires did more good than harm since he was trying to clear his land and after the trees were burned they could be pulled out easier. Cost of fighting the fire was $28.25.

Ranger Stations and Lookouts

Forest Ranger Brown sent a force of his guards — Billings, Petit, and Patterson — out Monday to begin permanent improvement work at different points in the Fremont National Forest. Ranger stations will be built at Silver Creek Marsh, Timothy Meadows, and several other points of vantage. At these stations pastures will be fenced for the convenience of the guards and the traveling public. Many trails will be laid out, one of the most important of which will lead from Timothy Meadows to the top of Bald Mountain, and must have a grade that will not exceed 15 percent. From the top of this mountain a view of nearly the entire reserve is commanded and here will be established a sort of lookout station for observance of forest fires. This station will soon be connected by telephone with Ranger Brown's headquarters in Silver Lake. In case a fire starts anywhere in the forest, it will at once be observed by the lookout on top of the mountain, and a telephone message sent at once to headquarters, from where a force of men can be sent to fight the fire. On the 20th of this month, twenty additional men will be put to work to carry to completion as rapidly as possible the work that has been mapped out. (Silver Lake Leader, September 1, 1907)

Fire Patrol in the Early Days (Scott Leavitt). Cougar Peak was my lookout and I rode up it as far as I could and then climbed. Recall spotting a smoke, riding to it with pack outfit and fighting it alone until Ranger Bill Neff, having seen the smoke too, rode in and joined me. We caught it small and held it. No phones, no walkie-talkies in those days. No planes, no smoke jumpers either; just horses and rangers like Bill Neff and me. But neither were there so many people nor man-caused fires. (Scott Leavitt, October 8, 1962)

TIMBER MANAGEMENT

A sale of one million feet of yellow pine to the Oregon Valley Land Company is under way. Advance cutting will probably begin at an early date, and a mill with a capacity of 15,000 feet will be erected at once. The cutting area is located near Mill Creek in the Dog Lake District, and the sale is in charge of Ranger Sherman A. Brown.

The timber will be used for construction work by the company in putting in the system of dam and flumes which will carry the water of Drews Creek into the irrigation ditches projected to make fertile a large portion of the valley of Goose Lake.

The map and forest description prepared by Ranger Brown in connection with this sale, from data gathered by Ranger Musgrave and himself, deserve mention for their completeness. The map shows contour lines and furnishes a working plat for logging. In work of this sort, the excellence of such data is important.

Supervisor Ingram and Ranger Sherman Brown returned recently from Dog Lake station, where they had been engaged making some very necessary and sanitary improvements, and on their return marked 100,000 feet B. F. M. of timber for advanced cutting for the Oregon Valley Land Company, who will begin operation within the next few days. (1909)

WILDLIFE

Game Laws

Buck deer, mountain sheep, and antelope — closed from November 1 to July 15 of following year.

Female deer — closed from November to September 1 of following year.

Ducks, geese, and swan — closed from January 1 to August 15.

Trout — closed from January 1 to April 1.

Bag limits are as follows:

| Ducks | 25 per day, 50 per week |

| Deer | 5 per open season |

| Geese and Swan | No limit |

| Trout | 125 per day |

(Lake County Directory, 1908)

Wild Boar

While Sherman A. Brown and Mark E. Musgrave were at Dog Lake working on the experimental planting area broadcasting seed on the snow, they were attacked by a vicious wild boar which they killed with their revolvers. Had they not been armed, a tree that they could have climbed would have been their only escape. The tushes taken from the lower jaws were ten and one-half inches in length. ("Fremont Adviser," May 1, 1909)

LIVESTOCK

Allowances and Permits

When Guy M. Ingram became supervisor in 1907, the ranges were overstocked and overgrazed. One of the most difficult problems was to reduce the numbers of stock on the forest. The first thing was to eliminate from the national forest all stock of owners who did not own ranch property, and limit the number of stock allowed each permittee. Ownership of ranch property was the vital subject for consideration in making a 50 percent reduction in the numbers of stock allowed on the forest. Private land, including many sections of railroad land within the forest boundaries, was in many cases claimed by permittees who demanded additional stock therefore.

In the early days of forest administration it was difficult to determine which of the many grazing applicants should be given permits. When several applicants for the same range each claimed they had been using the range for the last twenty years, it was difficult to determine who were the best qualified. In most cases too many stock had been using the range, and it was badly overgrazed. Even after the permits were issued, the ranges continued to be overgrazed for many years before sufficient reductions could be made.5

| 1907 | Sheep | 116,300 | |

| Cattle and Horses | 25,000 | ||

| Swine | 300 | ||

| 1908 | Sheep | 90,000 | (Goose Lake) |

| 28,000 | (Fremont) | ||

| Cattle and Horses | 21,500 | (Goose Lake) | |

| 6,000 | (Fremont) | ||

| 1909-10 | Sheep | 110,000 | |

| Cattle and Horses | 26,000 | ||

| Swine (1910) | 150 |

| Grazing Fees: Cattle and Horses | |

| Season — April 15 to November 15 | |

| Cattle | Horses |

| 1907-1909 | |

| $ .25 | $ .35 |

| $ .40 yearlong | $ .50 yearlong |

Grazing Fees: Swine | |

| Season — April 15 to November 15 Yearlong available beginning April 15 | |

| 1908 and 1910 | |

| $ .15 | |

| $ .25 yearlong | |

Grazing Fees: Sheep | |

| Season — June 15 to October 15 April 10 to October 15 available starting 1908 Extension to November 15 for additional $ .015 | |

| 1907 | |

| $ .07 | |

| 1908 | |

| $ .07 | |

| $ .10 extended season beginning April 10 | |

| $ .08 shortened season April 15 to June 15 | |

| $ .02 lambing | |

| 1909-1910 | |

| $ .07 | |

| $ .05 shortened season April 15 to June 15 | |

Stockmen

In 1907, the wages of a herder were $30 to $40 a month, buckaroos $40 to $75 a month, and wood choppers $2 to $2.50 per day.

Predators and Other Nuisances

In the neighborhood of 1,000 head of sheep have been poisoned during the past ten days along the road between Lake Abert and Lakeview. A mineral of some sort, possibly arsenic, is supposed to be the cause of the loss.

Stomachs as specimens have been secured from two sheep and sent to the state bacteriologist at Corvallis, Oregon, for diagnosis. A report of investigation will shortly be received, when precautions may be advised from this office to prevent future losses.

The specimen of supposed sheep poison brought to this office by Mr. Fisher from the Bald Hills and which was sent to the Department of Bacteriology at the experiment station some time ago for analysis proved to consist purely of infusorial earth of the globular form and is thought not to contain any material poisonous to sheep. (May 1, 1909)

W. R. Hammersly, whose appointment as hunter in the Forest Service went into effect March 11, has been doing excellent work. To date, he has taken the scalps of thirty-four coyotes in the Drews Valley country. Lambing is near at hand, and the damage which these animals would have done even during that period alone would far out balance the expense of their extermination. ("Fremont Adviser" April, 1909)

W. R. Hammersly is still doing excellent work. He has rid the range this past month of twenty-five more coyotes and two wild cats. This makes a total for the two months he has been employed of fifty-nine coyotes and two wildcats. ("Fremont Adviser", May, 1909)

Range Violence

While the range wars had been responsible for the destruction of thousands of sheep during the period from 1900 to the establishment of the reserves in 1906, no sheep killing was recorded after the reserves were put under administration in 1907. However, future difficulties did occur.

In 1910 Ike Harold was herding sheep for Walter and Herbert Newell, sheep permittees on the Warner District. Because he had mixed two bands of sheep, his employers were dissatisfied with his services and decided to replace him. Herbert Newell went to Plush from the sheep camp on Honey Creek to make arrangements for shearing and to bring out a new man.

Upon returning to camp Herbert Newell told Harold that he would write him a check and pay him off. He started to write the check when the herder came up and hit him with the gun. Walter Newell, who was standing near, came up to Ike Harold and said, "You hit my brother." The herder turned to him and shot him through the heart. Herbert then sat down and wrote a note saying, "Ike Harold has killed Walter; he has hit me and I think I am going to die." Ike Harold then shot Herbert through the head. Dick Allen, the new herder, was a witness to the whole affair, but he was so frightened that he left at once for Plush where he hid for two or three days before telling anyone of the murders. He finally told Tom Sullivan about it and then an intensive search was started for the killer.

The search was led by Charley Arthur, deputy sheriff, and O. T. McKendree. A reward of $2,000 was offered for the capture of Harold. A party of twenty-two men searched the Chewaucan country. Arthur's crew of sixteen men hunted and tracked him for two days in the vicinities of Honey, McDowell, and Mud creeks. Some of the party found where he had cooked a rabbit and sagehen and where he had been fishing. He was captured on Mud Creek by Arthur and McKendree, who shot the gun out of his hands. Judge Nolan sentenced him to be sent to Salem and hanged.

During the time he was in jail and even after he went to Salem, he was cheerful and joked with the other prisoners about being hanged. However, when the day came for him to climb the thirteen steps, he had to be carried up. (Charley Arthur)

IMPROVEMENTS AND OTHER FOREST SERVICE OPERATIONS

Ranger Districts

At the beginning, dating from February 1, 1907, the forest administrative regions consisted of the Goose Lake and Fremont forest reserves. This area was divided into four districts — Warner, Goose Lake, Paisley, and Silver Lake. The Silver Lake District at that time included an area extending from a line west of Paisley, Oregon, westward to the Klamath Indian Reservation several miles north of Hagar Mountain, north to a point south of Bend, west to the summit of the Cascade Mountains, and east to the desert.

In 1908 and 1909, five districts were shown — Warner, Dog Lake, Thomas Creek, Paisley, and Silver Lake. In 1910, 1911, and 1912, a sixth district, Summer Lake, was listed.

Roads

The Currier Trail Wagon Road, built in 1908 and 1909, was the first road constructed in the Paisley District. The costs were as follows:

| Labor | $1,549.25 |

| Groceries | 440.76 |

| Tools | 168.25 |

| Camp Outfit | 66.08 |

| Total | $2,224.34 |

Citizens subscribed $555.00 for the road.

Buildings

Construction of the first ranger station houses was started 1909. They were Dog Lake, Ingram Station, Thomas Creek, and Oatman Flat. The sum of $25 was allotted for each house, and most of the construction was done by ranger force.

Relinquishment was secured from Mrs. Elizabeth Ward for the S1/2SE1/4 Section 21, and N1/2NE1/4 of Section 28, T.28S., R.14E., W.M. and improvements consisting of a four-room house and fencing on claim, were purchased for $500.00

The Foster ranger station is being cleared by Assistant Ranger Abbott. This station is destined to become one of the most important on the forest. It is capable of producing fruit and vegetables and enough alfalfa to winter all the horses belonging to the force. ("Fremont Tidings," April, 1909)

The following ranger station cabins have been completed to date: Dog Lake, Rogers, Thomas Creek, Salt Creek, Norlin (nine miles south of Currier Camp), Foster Flat, Oatman Flat, and Billings. (November 2, 1912)

Telephone Lines

The Dog Lake Telephone Line, built in 1908 and 1909 was paid for by transferring $160.00 from the Cougar Peak ranger station pasture fence. The six miles of telephone line connect the Oregon Valley telephone line with the Dog Lake ranger station. Costs were as follows:

| Wire | $ 42.14 |

| Freight on wire | 7.90 |

| Supplies | 14.41 |

| Hauling | 11.00 |

| Labor | 48.75 |

| Board | 17.25 |

| Total | $141.45 |

The ZX Company has signified its willingness to cooperate with the Forest Service in the construction of a telephone line from Paisley to Sycan, and the forester has been asked to increase the authorization of the forest sufficiently to permit the work's being done. The value of such a line needs no explanation. ("Fremont Advisor," April 1, 1909)

The following Forest Service telephone lines are completed to date:

Approximately ten miles of line from Thomas Creek station to connect with over five miles of private line that comes to Lakeview

Lakeview to Rogers ranger station

Salt Creek, about two miles to connect with private line

Foster Flat ranger station line, about two miles from Foster Flat to connect with private line in Summer Lake Valley

Dog Lake, about six miles of line from Dog Lake ranger station to connect with private O.V.L. line on west side. (November 2, 1910)

Meetings

A ranger meeting in Roseburg in October, 1907, was attended by the Fremont force, all of whom were outfitted in new uniforms. It was reported that the Fremont was the only forest with all officers in uniform. Ranger Gilbert Brown and Guards Jay Billings, Jim Brady, Jason Elder, and Frank Petit traveled in Brown's wagon from Silver Lake via Fort Klamath, Pelican Bay, and Ashland to Roseburg, where they arrived October 17. Supervisor Guy Ingram and Guards Scott Leavitt and Mark Musgrave traveled from Lakeview. The meeting lasted until October 25, and the Fremont officers arrived back home October 29.

The first ranger meeting on the Crater Forest was held at Odessa for the Crater and Fremont personnel October 18-21, 1909. Attending from the Fremont were Jay Billings, Lawrence Frizzell, Pearl V. Ingram, Elzie Linville, Carl Ewing, Jason Elder, Gilbert D. Brown, Guy Ingram, Martin O'Brien.

Miscellaneous

Stones. A sale of 200 pieces of stone at $ .01 each was made March 15 to F. M. Chrisman at Silver Lake (1909)

Fremont Map. An authentic map of the Fremont has been prepared by Sherman A. Brown from land office records, and the data furnished by the district rangers. A copy of this map will be sent to each ranger probably by the middle of May. The tracing is too large to print in the frame here and will be sent to Portland or Washington.

Protest. I wish to enter a protest against some of your Rangers and the facts are these I loaned my buckboard to two of my neighbors to go to Rosland (LaPine) with while there on the Knight of the 20 inst two of your rangers staid there and some one branded my Buckboard with U. S. no less than 57 times no part of it escaping it is litterly Branded all over if one or both of them did not do it they furnished the tools as no one else has that identical brand it also corresponds to a Brand placed on my Bob sled by a Ranger last season further remarks upon such acts of vandalism is unnecessary at this time. (Correspondence received in the Lakeview supervisor's office, 1907)

Early Days on the Fremont

Gilbert Brown in Silver Lake. The early days at Silver Lake were exciting and sometimes dangerous as experienced by Gilbert Brown, ranger in 1907. There were many cases in which people tried to obtain forest timber land under the June 11 Homestead Act, which was contrary to law.

On several occasions Gilbert Brown assisted the sheriff in arresting criminals for crimes committed on or near the national forest:

Hamilton at Silver Lake had killed Wande, and Brown located Wande's body where it had been thrown into Silver Creek.

Ed Lamb was shot at Paisley, and Mr. Brown assisted the sheriff in arresting the murderer — Lamb's wife.

One day a cattleman rode into Silver Lake and a sheepman pulled a knife and severely stabbed him. When told to have the sheepman arrested, he replied, "No, this is a personal matter. I don't wish to have him arrested." A few days later the sheepman was found shot to death in his cabin. No questions were asked!

Personal Accounts

Gilbert Brown. In one case a man tried to homestead a tract of land which I had recommended be set aside for a ranger station. As my assistant R. B. Jackson and I were leaving Silver Lake one morning, the saloon keeper stopped us and said that a certain man had threatened to kill me; that he was drinking and dangerous. We road on to Foster Flat, sixteen miles south of town, and as we were eating supper by a camp fire, we saw him coming across the meadow toward us, his horse on the run, and he was swinging his six-shooter.

Jackson remarked, "I guess the saloon man was right! Stop him!" I grabbed my carbine, which was in the scabbard on my saddle by the fire, intending to shoot to frighten him, but when he was about fifty yards away, I yelled to him to throw his gun, or I would shoot. He threw his revolver to the ground, and we ordered him to come on up to the camp. We got his gun, gave him supper, and as he had run his horse much of the way from town, Jackson divided his bed for the night. The next morning he left, and I never saw him again.

One evening I was sitting in the old Chrisman Hotel in Silver Lake, talking to a friend, when some shooting occurred across the street in a saloon — a supposedly soft drink place. Soon three men came into the hotel, two of them supporting the one between them, who said he had been shot. I asked who had shot him and he said, "Jeff Howard." The man had a hole burned in his mackinaw coat over his heart. I pulled his coat open and a .38 caliber bullet dropped to the floor; it had not even pierced his shirt. I asked him what he had done to Howard, and he said, "I killed him."

We rushed over to the saloon and found Mr. Howard, an elderly man, bleeding freely from a wound in the neck. We placed him on a billiard table and applied first aid to the best of our ability, stopping the bleeding. We found out later that two men had come into the place and one of them started shooting up the lights, when Howard ordered them out. They kept on shooting and Howard reached under the bar, pulled out a .45 caliber gun and, thrusting it against the man's breast, pulled the trigger. The .45 was fully loaded, but one chamber had a .38 shell in it, being the one that was fired; consequently, there was little force in the bullet, and powder burned only the heavy mackinaw coat. However, it either knocked him down or he fell down from fright, then, jumping up, he fired his own gun, hitting Howard in the neck, the bullet passing around and out through the skin without producing a vital wound.

The miracle was that Howard had the .38 cartridge in one chamber of his gun and failed to inflict a wound, while the man who shot him pulled a little too far to the right, hitting the right side of the neck. I telephoned the sheriff at Lakeview, 100 miles south, and he requested me to obtain the guns and to hold the men until he arrived, which took several hours. Howard was sent to the hospital at Bend and recovered. The other men were taken to the Lakeview jail.

Scott Leavitt. That summer (1908) George Wingfield, who had been a boy in Lakeview and had become a millionaire in Goldfield, Nevada, came to Lakeview with an automobile and a chauffeur. I was driving into Lakeview with a sheepman's team and my saddle and packhorse tied on behind the wagon. We had come well on the slash road, with swamp on each side, when that contraption loomed up in the dusk and turned on its lights. Neither the horses nor I had ever met such a thing. Every horse tried to go in a different direction, so, with me sawing on the lines, we stayed on the road just waltzing around. Wingfield put out his lights and helped get the horses past the darkened car.

That same year a forest guard who wanted to be a ranger chanced on a small burn centered by a lightning-shattered tree. The fire was out, but he tacked one of those old cloth fire warning signs up to inform the creator of the penalty of setting fires in the woods. That guard faded out of the Service when the supervisor found him for the second time fishing instead of being on patrol. "Funny thing," said the guard. "Here I've fished only twice this summer and the supervisor caught me both times."

No story of those early days of the Forest Service would be complete without a tribute to the wives of the old-time rangers. To be sure, there were humorous incidents which my wife recalls, such as the time the supervisor came by when I was out on my district and found her with a black eye. He cocked a questioning eye at my later explanation that I had gone away without leaving her enough wood, and she, in breaking a limb with the axe, had caught a flying chip in her eye. At that, I guess even the truth didn't leave me blameless.

But there was also the time I was out with a sheepman locating an allotment line. We followed a section line by the old blazes, left our horses at a place too steep to ride, and then, far away from our horses, discovered that the survey crew had blazed only one side of the trees. It got dark and a storm blew up, so we built a fire and spent the night in the rain. Early in the morning we rode to his camp, and it was afternoon when I got back to the cabin. Then I realized what it had meant to my wife. She had gone out to the corral time and again to see if my horse had come back without me. She had called and listened and gone back to her babies to wait. We men, of course, took that sort of experience as part of the work, but I realize now what heroines those wives of the old Service were. (Scott Leavitt, October 8, 1962)

LOCAL NEWS

Historical Names

Lakeview. In the 1870s, Goose Lake was full enough that its northern banks extended to the present site of the Southern Pacific Depot at Lakeview, and was clearly visible from the mouth of Bullard Canyon where Lakeview was built, hence the name. The town was started in 1876 for the express purpose of taking the county seat away from Linkville (Klamath Falls). When the legislature took the present Klamath County and most of the present Lake County away from Jackson to form the new Lake County (effective February 1, 1875), it named Linkville as temporary county seat with provision for the residents to choose the seat by ballot. In the first vote (June 1876), there was no town around Goose Lake, but most of the new county's settlers were in that area. The seat remained at Linkville, but a second election was held in November of the same year, and in the meantime the settlers got busy and built a town, calling it Lakeview, and the seat was moved there in December.

Goose Lake. Goose Lake was named for its importance as a resting and feeding place for the migratory birds. The lake is about forty miles long and fifteen miles wide, about two-thirds of it being in California, one-third in Oregon. At its deepest, the lake is only fifteen to twenty feet deep, but mostly very shallow. It has no effective outlet, but records show it has drained southward into Pit River. In the land boom days following the turn of the century, a number of commercial-sized boats, both excursion and freight, plied the Goose Lake waters, but none has been on the lake since the early 1920s. The earliest was a 75-foot steamer in about 1881 that was used for one season only for wood hauling and excursions.

Warner Mountains. The Warner Mountains were named for Captain William H. Warner, who in 1849 led a party of soldiers out of Sacramento to explore this area and find a route to Fort Hall. In September, the day has been variously reported at the ninth and twenty-sixth, his group was ambushed and he was killed. The range of mountains of Warner Valley has been named for the captain. The exact location of the ambush has not been established, but it is thought to have been near Surprise Valley.

Abert Rim and Lake. When Captain John C. Fremont and his party, including Kit Carson, passed through here in December 1843, he named these two landmarks for his superior Colonel J. J. Abert, chief of the army's Division of Topographical Engineers. Abert Lake is a beautiful body of water from the air, but is too alkaline to support fish life.

This is the largest exposed fault in North America — about thirty miles — and the second largest in the world. It may be said that millions of years ago, in the Miocene Age, the country was covered by the great Columbia lava flow. Later, by some cataclysmic subterranean action, this thick lava crust was shattered, and sections of it upheaved, tilted, or dropped down, forming many great fault scarps with corresponding depressions at their bases, which later became lakes. Along the east shore of Lake Abert, twenty-five miles north of Lakeview, Oregon, is the Abert Rim, rising a sheer 2,000 feet and showing 800 feet of superimposed lavas layer upon layer. Highway U.S. 395 hugs its base.

Summer Lake and Winter Ridge. Both were named by Fremont. Coming through deep snows in that December 1843, his party arrived at the top of the towering rim and looked down at the lake, where the green grass was growing. The names were obvious.

Christmas Lake. Early pioneers named this always dry, prehistoric lake bed, but the reason for the name is not known. Some have claimed that Fremont named it, but he did not go that way. He swung south from Summer Lake, past Abert Lake and into Warner Valley where he did give the name "Christmas" to a lake. Camped on the lake shore Christmas Eve, the party celebrated the arrival of Christmas morning by firing their one cannon, and Fremont named the lake Christmas. However, the name did not stick, and the lake today is called Hart Lake.

Fort Rock. This landmark gets its name from the shape of the ancient volcanic cone wall which towers above the desert. Contrary to some claims, it was not used as a fort.

Hart Mountain. This mountain is often confused with Warner Mountain because of the location of old Fort Warner. According to Oliver Jacobs, who moved to the Hart Mountain area in 1883 and went to work for Henry and Johnnie Wilson, the Wilson brand on cattle and horses was a heart, thus giving the name of "heart" to the ranch and vicinity with usage establishing a shorter spelling. Concern for the preservation of the pronghorn antelope led to Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge in 1936. This 240,000 acres was obtained from private owners and public domain.

NOTES

1. Goose Lake is not shown as a distinct district after 1907. In July, 1908, the Fremont and Goose Lake Forest Reserves were combined. Bach, pages, 33, 37, and 50.

2. The Paisley District at this time included Rosland, now called LaPine. Bach, page 37.

3. The lake was first called "Dog Leg" because of its shape, but the name was later changed to Dog Lake. Bach, page 46.

4. For the complete editorial, see Bach, page 74.

5. Bach lists some of the earliest permittees as well as the number of permits issued on pages 48-49. Information on maximum limits and changes in these are given on pages 52-53, 55, and 57. For protective limits and changes in reductions see pages 68-69.

|

| First Dog Lake Ranger Station, 1909 |

|

| Logging on the Silver Lake District for the Embody Mill, circa 1907 |

|

| Fremont National Forest Office in 1909. Left to right: Gilbert D. Brown, Scott Leavitt, Vada Bonham, Guy Ingram |

|

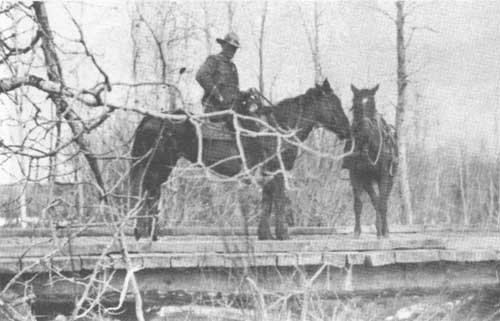

| Gilbert D. Brown, Silver Lake Ranger, on the first bridge built on the district, circa 1907 |

|

| Hunting trip in 1908. Left to right: Warner (Buck) Snider, A.L. Thorton, Gilbert D. Brown, Guy Ingram, Mark Musgrave. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

fremont/history/chap2.htm Last Updated: 01-Feb-2012 |