|

A History of Forest Conservation in the Pacific Northwest, 1891-1913

|

|

CHAPTER 5

RESERVES IN WASHINGTON, BOUNDARY WORK, 1897-1907

The boundary work in the Northwest between 1898 and 1907 is of interest from several points of view. From a technical point of view, the work was one of the first large scale governmental efforts in land classification, and illustrates some of the difficulties this presented. Administratively, it illustrates some of the difficulties presented by having the work under the jurisdiction of several bureaus, and the effect of local pressure groups on these governmental bureaus. The work also demonstrates some of the differences between the two states, and sub-regions within the states.

It will be remembered that three bureaus, and two departments, had their fingers in the pie in regard to the reserves. The Land Office had charge of administration of the reserves. The Land Office was a political bureau, with untrained personnel, and subject to local pressures. The Geological Survey, until 1902, had charge of survey of old reserves, and recommendations of new ones. The Survey was a group of professionals, who had good technical training, but who were solely technicians. They did their work quietly and with no publicity, and made little attempt to direct or educate public opinion. Both these bureaus were under the Department of the Interior. The Bureau of Forestry after 1902 had charge of boundary work. This was also a professional group, but they regarded as one of their tasks directing and educating the public, and had due account for public opinion, as well as other aspects of the case, in recommending creation of new reserves. This bureau was in the Department of Agriculture.

In Washington, the fact will be remembered that the reserves there—the Washington. the Olympic. and the Rainier had been created arbitrarily, on recommendation of the Academy committee, rather than because of grass-roots desire for reserves. It was natural, therefore, that the first opposition to the reserves came against these. The later reserves, created on recommendation of the Bureau of Forestry, met with much less opposition.

I. The Olympic Elimination

In 1898, after the nine-month open season, the Cleveland reserves were reestablished and the work of administering them began. In western Washington, particularly on the Olympic Peninsula and in the tier of counties on the west border of the Cascades, the period 1898-1907 was marked by a series of sporadic protests against the reserves. The reserves were heavily timbered; the speculative boom in timber was at its height, and the reserves often interfered with speculative or cutting plans. One such area was the Olympic Peninsula.

The Olympic reserve was of large proportions, covering as originally created 2,188,800 acres. Most of the area was mountainous or timbered. A few prairie openings existed on the north side of the peninsula, not totaling over four thousand acres in all, which had in 1898 been taken up by settlers. On the northwest and west sides, the terrain was rolling for a distance of three townships back from the coast; and here, too, much land had been taken up under the Homestead and the Timber and Stone Acts. In the opinion of the Geological Survey investigators, however, the land could hardly be called agricultural, since it cost $150 to $200 per acre to clear. This fact seemed demonstrated in that though 341 homestead entries had been made within the limits of Clallam County only 83 people could be found residing on their tracts.

The area was the moat heavily timbered section in the United States, with a dense stand of Douglas fir and hemlock, and local stands of Sitka spruce and red cedar. Little logging was being carried on at the time of the survey, except in R. 9 W., T. 30 N., W.M. The rivers, like most in western Washington, were swift, subject to freshets, and with many bars due to the abrupt decline in grade from mountain to flat; they were poorly adapted to river drives. Though the terrain was suitable for railroad logging, as yet no railroads had been built in the area. [1] Nevertheless, logging companies had their eyes on the timber, and were obtaining title one way or another. 66,160 acres were railroad lands, and much of this passed to subsidiary land and logging companies such as the Weyerhauser interests. Other companies, less fortunate in their associations, had many dummy entrymen making entries under the Timber and Stone Act—a practice which benefited both federal government and entryman, according to the historians of the Pope and Talbot Company. [2]

The reserve had no sooner been established than protests began to come in demanding that its area be cut down, using arguments that the land was predominantly agricultural and that reserving it held up development of the country, The local management was poorly equipped to deal with the situation in a strong fashion. The supervisor of the reserve was Dr. W. W. Cloes, a political appointee, and a dentist by profession. He may have been a good dentist, but he was a poor conservationist, ignorant of his job and far too willing to give local pressures his own endorsement. As one settler remarked, "If Cloes' judgment ain't any better on teeth than farming he couldn't look in my mouth that is all." [3] Cloes made an examination of the reserve in November, 1898, and recommended cutting down its size. Gifford Pinchot of the Bureau of Forestry and Henry Gannett of the Geological Survey rejected Cloes' report on the grounds that it would eliminate much of the good timber land. [4] Both Gannett and Pinchot were personally acquainted with the reserve, Pinchot having given it a personal examination in August and September, 1897.

In 1899 more protests came in, and once more Cloes made, or said he made, an examination. In a report dated May 11, 1899, he recommended that T. 24 N., R. 4 W., and T. 22 and 23 N., R. 5 W., W. M., be withdrawn from the reserve. These areas, he said, were heavily timbered, but there was also good agricultural land in the region, and settlers had been there for ten to fifteen years. In T. 21 N., R. 5, 6, and 7 W., W. M., he reported finding lands that had been "in the hands of large mill companies for years, and they are now logging them off." In T. 21 N., R. 8-11 W., he reported finding a hundred settlers. These areas also, he considered, should be withdrawn in whole or in part. [5]

Dozens of other petitions cane to the Land Office in 1899, praying for relief from the hardships wrought on the poor but honest settler by the reserve. The arguments advanced were plausible and at times heart-rending. Homesteaders who had spent the best years of their lives developing fertile farms in the region found their investment was for naught; Clallam and Jefferson Counties had lost most of the taxable land in their counties; schools would close and road bonds, owned by "widows and aged people in the east," would be defaulted; farmers already in the area would sell out for lack of markets and in order not to be caught in enlargement of the reserves. The Seattle Chamber of Commerce sent in a remonstrance, as did Senator A. G. Foster. [6] The government officials in charge of the reserve, however, were not impressed. In a letter to Binger Hermann, the General Land Office Commissioner, Charles D. Walcott, Director of the U. S. Geological Survey, wrote:

Concerning the representations which are being made that important local interests are suffering because of non-adjustment of the lines of this reserve, I beg to state that the only interests which are suffering in the slightest degree are those of the lumbermen and millmen, who are desirous, naturally, of having large areas of the best timberland in the reserve set aside from it. There is not an acre of land within the present limits of the reserve which, under existing conditions, is of the slightest value for agriculture. [7]

Probably primarily due to pressure from Senator Foster, D. B. Sheller, Superintendent of the reserves in Washington, made an examination of the reserve. Sheller was another political appointee, a former member of the state legislature, but he was of different caliber from Cloes. Cloes was worthless on all counts; Sheller was a man of good will, with no professional training, in a job that was too big for him. He made attempts to enforce the laws against forest trespass and fire, but could not get convictions because of hostility toward the forest administration. In trying to achieve a successful administration he had little support from the Land Office officials and little aid from subordinate officials. His later career, however, may indicate that his failure to deal in an adequate fashion with the Olympic situation was not a sign of complete lack of ability. [8]

In September Sheller made an examination of the reserve. His examination of T. 21 N., R. 5-11 W.: T. 22 N., R. 5-6 and 8-11 W.; and T. 23 N., R. 5 and 10-11 W., W. M., indicated the presence there of eleven settlers and no agricultural land (Cloes had found 100 settlers). In the west of the reserve, however, he found a different story. There were a scattering of settlers here in the stream valleys and prairies; ten on the Queets River, four on the Hoh, several on the Bogachiel, twenty-five at Forks, twenty at Quillayute Prairie, and others around Lake Crescent. Though settlement was relatively thin, he thought that the timber in the area was of poor quality, and the land better suited to agriculture than lumbering. The fir and spruce, he reported, were of poor quality, and much of the timber was of a poor grade hemlock. The only merchantable timber, he found, was along the Soleduc and Galawah Rivers, and in T. 21, 22, 23, and 24. The settlers there, he believed, were bona fide residents who had filed on their claims without speculative intent; although many had sold out to scrip speculators when the reserve went through, for fear of being isolated. Sheller concluded by asking for revision of the reserve boundaries. [9]

Sheller's report was backed by that of the field men of the Geological Survey, Theodore Rixon and Arthur Dodwell, who had just completed their examination of the area. They reported that the lumber industry had no immediate future there; there was no market for hemlock, and the fir and spruce were of poor quality. They also believed that the reserves were holding up development of Clallam County. During the boom days of the 1890's there had been a rush to the area, and many clearings were made, averaging perhaps forty acres out of a quarter section. These settlers had been bona fide farmers, rather than speculators. [10] Gannett denounced both reports. Sheller, he said, was not a qualified observer as to the value of the timber there, which field notes of the Geological Survey indicated was much higher in value than his estimate; and he also had the wrong idea as to what constituted agricultural land, believing that any level ground was agricultural, while in reality, Gannett said, it was that soil better suited for growing crops than growing trees. As to Dodwell and Rixon, they had been swayed by the protests of the settlers. [11] The final decision was not up to Gannett, however, but to the Department of the Interior; and on April 7, 1900, it acceded to the pressure from settlers and others, and eliminated 264,960 acres from the reserve. Gannett himself, probably with some reluctance, acquiesced in the decision. [12]

Agitation for further eliminations from the reserve came during 1900, presented mainly through Senator Foster and Representatives Jones and Cushman. These duplicated the former requests in containing statements that the land was primarily agricultural in nature, that the tax rolls of the counties suffered, and that development of the country was held up. On July 15, 1901, a further reduction was made of 456,960 acres. [13]

Most of the "agricultural" land in the area eliminated from the forest went into the hands of logging companies. From that standpoint, the elimination had all the aspects of a land swindle. [14] Forty-two per cent of the land in the area eliminated were Timber and Stone entries, in itself an evidence of fraud. Of the land taken up under the Homestead Act, two thirds went to logging companies. A fair share of the entries may have been made in good faith, since the Homestead Act was not the easiest by which timber land might be taken up; but the rising price of timber, the increased use of hemlock, and the fear of becoming isolated as others sold out led to these entries also going to the logging companies.

II. The Whatcom Excitement

The protests against the Olympic reserve had their counterpart in protests against the Washington reserve. Creation of this reserve in 1897 had been greeted by howls of anguish from miners, as will be recalled. The act of 1897 provided that mining could be practiced in the reserve; and this, combined with the fact that the mining bubble broke in 1898, caused protests against the reserves to die down from this group. The area did contain valuable timber resources, however, and the desire of loggers to get hold of them caused a long battle between the forest administration and the timber interests.

In 1899 a whole series of protests came in to the Land Office, asking for elimination from the reserve of T. 29, 30, 31, and 32 of R. 8, 9, 10, and 11 E., W. M. The arguments were the familiar ones that all the land between the two forks of the Stillaguamish River was agricultural in nature; that settlers had already entered the area and built homes, schools, bridges, roads and such improvements; that the railroad had encouraged settlement, and that the reserve removed land from settlement and taxation, and was driving the county to bankruptcy. The protestants included the Chamber of Commerce of Everett, the Monte Cristo Railroad Company, the board of County Commissioners of Snohomish County, and numerous alleged settlers from the area concerned.

The area was examined by both the Land Office and the Geological Survey, and the statements in the petitions were found to be completely false. The Geological Survey stated that the only arable land was a narrow strip along each fork of the Stillaguamish, and that this area was needed for fire protection. D. B. Sheller also made an examination, finding the area mostly timbered. He found only fourteen settlers in the area, and judged that they were there to speculate in timber. As a result of these reports, the Land Office recommended that no changes be made in the boundary. [15]

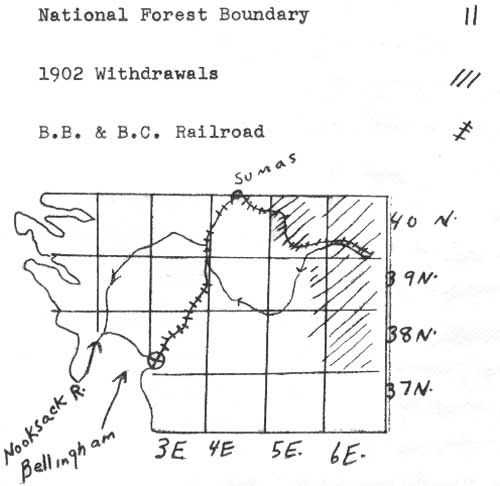

A year later another set of remonstrances reached the Land Office, this time from Skagit and Whatcom Counties. These were inspired by the logging and railroading interests of Bellingham, and were led by J. J. Donovan. A New Englander by birth, Donovan had come to Washington state about the turn of the century and had rapidly become interested in various types of speculative ventures. At this time he was General Superintendent of the Bellingham Bay and British Columbia Railroad, a line with its western terminus at Bellingham. The line ran east by way of Sumas, on the Canadian border, along the north fork of the Nooksack River to its eastern terminus at Conell, in T. 39 N., R. 7 E., W. M. just within the reserve.

The reserve interfered with Donovan's plans for two reasons. First, the charter of the railroad allowed an extension of the road to Spokane. Donovan had made a survey, and located a suitable pass; but he felt that all the timber along the right of way, between the middle and north forks of the Nooksack River, would be needed to finance the road. Second was the fact that the reserve cut down on the amount of timber available for his and his associates' logging interests (see Map 1). Donovan was well able to make his protests heard. Bellingham was a company town, dominated by the J. H. Bloedel and Peter Larson logging interests, in which Donovan had a share. He also had shares in the bank and business houses of the city. In addition, he owned stock in the two Bellingham newspapers, which were controlled by the Sidney Perkins interests. These papers were mouthpieces of the conservative wing of the Republican Party in the state. Donovan himself was a good party man, his name showing up periodically as a delegate at the state conventions of the Republican Party.

MAP 1

SCENE OF THE WHATCOM EXCITEMENT

The protests came because of some new withdrawals made in 1902. At the time of the creation of the reserve, in 1897, there had been a rush to the area bordering the reserve in Whatcom County, where there were large bodies of timber. The settlers had applied for a survey of the area, and a survey was made in 1898, but it failed of approval in the Land Office because of errors. However, lines had been blazed well enough to locate the more desirable bodies of timber, and lumbermen set to work to acquire these. Timber locators flocked into the area and, for a fee of $50 or $100, placed men on claims, surveyed or unsurveyed; built cabins for them of cedar shakes; built a fire in the corner of the cabin, and furnished the cabins with frying pans, coffee pots and other kitchenware as evidence of occupancy. Claimants were furnished blank contracts by which they promised to turn over their claims to the lumber company (see illustration 1). In this way, 6,080 acres were filed on in the area, in addition to a large tract in T. 38 N., R. 6 E., W. M., selected by use of railroad scrip of the Northern Pacific and the St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba lines. In 1902, however, on the recommendation of the Geological Survey investigations, extensive temporary withdrawals were made in the region.

ILLUSTRATION 1

COPY OF BLANK CONTRACT FOUND (IN A SQUATTER'S CABIN IN T. 34 N., R. 7 E., WASHINGTON)

__________________ Wash., ______190

To __________________

IN CONSIDERATION of the sum of One Dollar to __________________ paid by you, and in consideration of the benefit __________________ expect to derive from the sale of the property below described, __________________ agree to convey to you or such person as you may name, free from encumbrances, by General Warranty Deed, the following described property, situated in _________ County, Washington, to wit: __________ __________________ __________________ __________________ with all the appurtenances; upon the payment to __________________ by you, or by the person named by you, of the sum of __________________ Dollars ($__________________) lawful money of the United States.

This consideration is to remain in force for the period of ________ days from this date. __________________ agrees to furnish a complete abstract of title.

WITNESSES

__________________ __________________ (SEAL)

__________________ __________________ (SEAL)

(From W. T. Cox, "Report on the Proposed Addition to the Washington Reserve in Skagit and Whatcom Counties, Washington," N.A., D.A., F.S., Research Compilation Files, Region 6, dr. 137.

(click to see a facsimile of the original illustration)

Donovan began his attacks in a forthright manner, without resorting to the threadbare pretext that the reserve was agricultural land. The Whatcom Daily Reveille for January 9, 1903, quoted a letter from Donovan to the Office of the Register and Receiver cf the county, pointing out that two thirds of the county was in the reserve, whereas King County was under no such handicap. The following day the paper reported rumors that the recent additions to the reserve were part of a scheme by the Hill interests to keep the Bellingham Bay and British Columbia Railroad from reaching the east side and competing with them. Later, as President of the Whatcom Commercial Club, Donovan got that organization to send in a petition asking for a reduction in the size of the reserve; this was accompanied by numerous other petitions from the Sumas Commercial Club, the Republican and the Democratic county conventions, and a large number of alleged homesteaders, all protesting the additions. The movement spread to other counties. In Skagit County, surveys were made for additions to the reserve along the Skagit, Stillaguamish and Sauk Rivers, and the Everett Chamber of Commerce, the Fairhaven and the Arlington Commercial Clubs, the County Commissioners of Skagit County, and a large number of alleged settlers, sent in petitions to their congressmen. Pressure was put on the state legislature, and that body passed Senate Memorial No. I, asking that the western boundaries of the reserve be changed.

A series of examinations were made by the Land Office, the Geological Survey and the Bureau of Forestry in 1903 and 1904. D. B. Sheller made the first preliminary examination; reporting to the Land Office Commissioner on February 26, 1903, he stated that the claims of the petitioners should not be taken at their face value, but should be carefully examined. The Chamber of Commerce protests, he wrote, were largely because of the influence of the timber interests; legislators might know better, but would back protests to please their constituents.

The Skagit County protests had no success. The examiners found the number of bona fide settlers had actually declined after the mining bubble had burst in 1898. Timber speculation was growing, however, with mills on the border of the reserve cutting up to 300,000 board feet per day. The investigators found the additions to be desirable, and they were made permanent additions to the reserve.

In Whatcom County, the Bureau of Forestry made an examination in 1903 and 1904. The examiners found the bona fide ranchers in the area satisfied with the temporary withdrawals; they had a good market with the remaining miners in the region, and did not favor further extension of the Bellingham Bay and British Columbia Railroad since it might force then to compete with Puget Sound growers. However, after his examination of the Nooksack area, W. T. Cox, the examiner, favored cancelling the 1902 temporary withdrawal in T. 38 and 39 N., R. 6 E., W. M., despite the fact that many of the entries had been fraudulent. He favored cancelling them on the following grounds:

1. That sixty per cent of the county was already in the reserve, and the only future development of the county lay in the east.

2. That the people had believed that after the creation of the Washington reserve in 1897 no further reserves would be created in the area.

3. That the timber was ripe for cutting.

4. That the number of reserves was growing, and it would create good will to have this one restored to its old boundary. [16]

Pressure was so great that the Forestry Bureau decided to sacrifice the timber land for the sake of better public relations. As E. T. Allen wrote about that time, "If the present dissatisfaction in the West is aggravated by un-wise administration and ill considered creation of the reserves, there may be a rebellion ending even in the abolishing of the reserves themselves." [17] H. D. Langille, who was in charge of the boundary work in the region, recommended elimination of the temporary withdrawal in Whatcom County on the grounds suggested by Cox; and this area was withdrawn from the reserve in 1904. Moreover, Langille made a statement that no further reserves would be created in the area.

In 1906-07 the issue came up again. This was the period of intensive field examination for new reserves; the area was re-examined, and the recommendation made that the portion previously released be restored. The Bellingham group and their friends in the state legislature and in Congress rose once more in their wrath, and again the Perkins press began new attacks on the reserves. Langille's statement was recalled, and the Forest Service did nothing to further its case when it claimed this was a clerical error. Finally Pinchot advised that in view of the opposition it would be well to let the matter drop; the timber, he thought, should be reserved, but it would be unwise to do so. [18]

III. Rainier Reserve

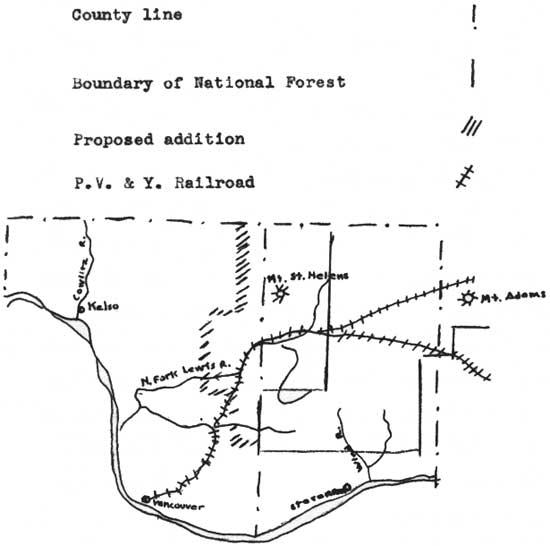

Railroads and timber lands played their parts also in the southern part of the state, in relation to proposed additions to the Rainier Forest Reserve. In Clark, Skamania, and Cowlitz Counties, the Geological Survey recommended additions to the western boundary of that reserve, involving T. 4-10 N., R. 4 E., and T. 6, 7, and 10 N., R. 3 E., W. M. Once more a storm of protests rose from those whose economic interests were threatened.

The first protests came from railroad promoters. There had long been a desire to have a rail line along the north side of the Columbia River to serve the region between Yakima and Vancouver; and sometime before 1898 a railroad company was formed to build a line between the two cities. The Portland, Vancouver and Yakima Company planned to build through the reserve. Their survey ran from Vancouver to Yacolt and thence to Chelachatie Prairie; reached Lewis River, and crossed at its junction with Canyon Creek; went up the river to T. 7 N., R. 8 E., W. M., and then forked, one branch swinging to the south of Mt. Adams to go down the Klickitat River, and to Goldendale, the other crossing the range at Klickitat Pass, north of Mt. Adams, and thence continuing to Yakima. The line, according to its promoters, would not only serve as a transcontinental link on the north side of the Columbia, but would tap the valuable timber resources in the area, and make accessible mineralized country around Mt. Adams and Mt. St. Helens. The road had received favorable backing from the Land Office. In 1898 the P.V. & Y. had built as far as Battleground, and was hauling logs from the operations there; but the reserve seemed to interfere with its further development. [19]

On November 18, 1898, L. Gerlinger, President of the Company, wrote to the General Land Office. He stated that the proposed addition would close half the mills in Portland for lack of logs, and destroy the prosperity of Clark County. The townships, he said, consisted partly of good timber and partly of farming land; but meantime 150 settlers there had waited fifteen years for the railroad to come to them. By building to the rich coal mines of Klickitat Pass, the road would make Portland independent of eastern supplies of coal. However, the line could not be built in a reserve, where it would be cut off from freight and passengers. Pleas of a similar nature came from the Portland Chamber of Commerce, the Vancouver Commercial Club, the Republican City and County General Committee of Multnomah County, and the Washington State Commissioner of Public Lands. [20]

MAP 2

RAINIER RESERVE

Similar protests came into the Land Office from Cowlitz County, from alleged settlers in T. 6-10 N., R. 3-4 E., and T. 7-10 N., R. 2 E., W. M. They swore that the reserve took up two thirds of the county, and made taxation burdensome by removing taxable land from county lists; that the area was essential for the sawmill operations, and in addition was valuable for stock raising and farming; and that county roads and trails were cut off from use. In their protests they were joined by the whole executive body of the state. Governor C. W. Rogers. Lieutenant Governor Thurston Daniels, Secretary of State Will Jenkins, and Treasurer C. W. Young all wrote to the Commissioner individually in November, protesting the proposed additions. [21]

The area was examined by the forest administration. J. W. Cloes left his dental chair long enough to make an inspection of the area. In his report of November 7, 1898, he wrote to the Land Office stating that the protests were nothing but a plot to get the timber. The land, he said, was not fit for agriculture, and there were few real settlers in the region. D. B. Sheller, who investigated the Cowlitz region about a year later, stated that the petitions for elimination of the area were signed by residents of the county, but not necessarily by actual settlers of the area mentioned. He stated that the chief dissatisfaction with the reserve was the removal of land from the county tax rolls, and the danger of curtailing logging. [22] The Oregonian also doubted the validity of the protests. The paper editorialized:

Two sets of objectors are met with, that are both interested in reaping immediate fruits from the land, regardless of the future. One of these is composed of sawmill men and timber sharks, the other of owners of large flocks of sheep, who seek to profit from the free use of what does not belong to them. Both these classes and their allied interests make a great outcry when it is proposed to reserve forest lands within their reach—lands which still belong to the public domain, and in which they have no greater rights than any other citizen of the republic. When the government proposes to reserve from settlement and sale a part of its own domain, such cries as that of the Kelso Journal "an attempted steal," or the Kalama Bulletin "a great outrage" are raised to stir opposition to the beneficent act and to defeat it if possible. . . . The time to reserve is when there is something to reserve. [23]

In 1901 the Northern Pacific began building its North Bank Road, and the value of the P.V. & Y. charter disappeared. [24] The next year the Yacolt fire swept over much of the area, and rendered the Lewis River area less valuable for timber. Protests over the addition died down. Nevertheless, the areas protested were eliminated from the reserve when the final boundaries of the forest were created. The land in question was in the foothills rather than in the mountains, and was tillable, though probably better suited for growing trees. Fire had destroyed most of the timber. Some of the protests of settlers were unquestionably genuine. Perhaps the deciding factor was the large amount of alienated land owned by the State, the Northern Pacific, and the Weyerhauser interests in the area in question. [25]

A few other remonstrances came in from that general area. In February, 1903, residents of Yale, Ariel and Amboy petitioned for removal from the reserve of T. 6 N., R. 3 E., W. M., on the ground that this was bottom and bench land, and that the 1902 fire had killed all the timber. In this they were backed by the Vancouver Commercial Club. In this case the petition was a justifiable one, and this area was removed. Far other were attempts to get land removed from the reserve along the Columbia River and in the wind River Valley. There J. W. Hull of Chenowith petitioned the President on February 22, 1902, for the elimination of T. 4 N., R. 4-9 E., W. M., from the reserve. His petition was backed by a long list of residents from Collins, Home Valley, Stevenson, Cape Horn and Carson. This was a bold and flagrant attempt to get timber land, since by no stretch of the imagination could the land be regarded as agricultural. About the same time Horatio Price of Vancouver, owner of the Wind River Lumber Company, asked for elimination of the lands in the Wind River Valley in T. 4 and 5 N., R. 7 E., W. M., on the ground that this was agricultural land. Investigation proved, however, that the soil was poor in quality, the land covered by timber, and the settlers were in the habit of selling out to the lumber company as soon as they proved up their claims. The company had already acquired 3,360 acres of land in the townships mentioned, and desired to get it all. Some homesteaders were found in the bottom land, but they were of the three-weeks variety, who cut a small clearing and lived on the land only long enough to hold it. Both these petitions were denied. [26]

IV. Other Reserves

Other areas were less hostile, either because of need for the reserves in the locality concerned, or because the work cane under the Bureau of Forestry, which took pains to educate the public as to the reasons for, and the value of, the proposed reserves. The rapid growth of Seattle made that city, like Portland, Ashland, and Baker City, consider the safeguarding of her municipal watershed. On October 10, 1899, the city sent a request, through Congressman Cushman, to the Commissioner of the General Land Office, asking for reservation of fifty sections in the Cedar River Watershed. On Sheller's examination and recommendation, the withdrawal was made. [27]

In 1903 and 1904 R. B. Wilson of the Bureau of Forestry examined the area between the Washington reserve to the north, and the Rainier reserve to the south—the area that later became the Snoqualmie National Forest. The forest included both east and westside forest types, but with an "overlap" to the east, making a five to one ratio of Douglas fir to yellow pine. The chief value of the reserve, he found, would be in regard to irrigation on the east side. Plans were being made to convert three lakes on the east side—Keechelus, Kachess, and Clealum—into reservoirs, to increase the irrigating capacity of the Yakima River. The river could normally irrigate 325,700 acres; by enlarging the storage basins, the normal low flow of 800 cubic feet per second could be increased to 2,000. The forest would be valuable in preserving and regulating water flow. Water rights in the area was a complex problem; ownership of land in the region concerned included Northern Pacific lieu selections, claims of the Yakina Development Company, and Reclamation Service land. One company alone had filed on eight times, and another on thirteen times, the total water capacity of one of the lakes.

About half the land was alienated in one way or another, seventy per cent of this being railroad land, the remainder school land or land taken up by one of the various land acts. Most of the lumbering, however, had been carried on outside the limits of the reserve, and there was no actual settlement in the reserve itself. Sentiment toward the reserve was in general favorable. The general feeling that most of the desirable land had been alienated anyway, so there would be no harm in putting the rest in a reserve. Sentiment of the sheepmen would depend on whether they got grazing permits or not. There were large holdings of railroad land and logging company land in the area proposed to be reserved; but both the Northern Pacific and the Weyerhauser Timber Company had asked for cooperative work with the Bureau of Forestry in fire control and cutting plans as it was felt that this area would be a good place to carry on such work. [28]

Little opposition was registered to an extension of the reserve in the vicinity, in the neighborhood of Morton and Ashford. The area included a western spur of the Cascades, much of it burned, but with scattered old growth Douglas fir, and potentially a great timber producing area. Much of this area had been alienated also; most of the odd sections were in the hands of the Northern Pacific, and many of the even-numbered sections had been lieu selections of the railroad. The remaining land, some 87,000 acres, was recommended for withdrawal.

On the east side of the range, several changes and additions were made. In 1905 E. T. Allen recommended changes in the eastern boundary of the Washington National Forest, eliminating 1,600 acres from the reserve along the Methow River and adding 7,680 on the bench lands above. The elimination was on request of the Methow residents; the land, Allen reported, was no better than some in the forest, but the people desired it for farming. No objections came at the time to the additions, though later the Methow country became one of the trouble spots in the region over interpretation of the Forest Homestead Act.

Examination of the area that later became Chelan National Forest took place in 1906. The area was yellow pine country, with a sprinkling of lodgepole and red fir, and was needed as protective cover to safeguard water flow. The main use of the area at the time was for grazing. The area had been cattle country, but in recent years sheep had come in, and a sheep and cattle war had resulted in the slaughter of three thousand sheep. Stockmen and farmers were largely for the reserve; merchants and real estate men, who feared that the reserves would slow up development of the country, were in opposition, as were county officials who desired to stand in with the business men.

The report on the proposed Colville reserve, an area between T. 35 and 40 N., R. 27 to 40 E., W. M., recommended a large area to be withdrawn in the Kettle River Country. The area had a large stand totaling about 1.8 billion board feet of yellow pine, lodgepole and red fir, which had not yet been exploited. There was little opposition to the proposed withdrawal; the value of the reserve in protecting water flow, and the need for fire protection were recognized. [29]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

history/chap5.htm Last Updated: 15-Apr-2009 |