|

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81 |

|

Chapter I

Conservation Movement Comes to the Southern Mountains

Beginning during the 1880's, the Southern Appalachian mountains became the scene of a major logging boom which continued until the 1920's. It was begun and sponsored almost wholly with capital from outside the region. Within four decades, the logging boom dramatically altered the landownership pattern and influenced the economic and social structure of the Southern mountains. In addition, large-scale logging caused extensive damage to the mountain environment which drew the attention of conservationists in the region and in Washington, D.C. A movement to secure the protection of the Southern Appalachian forests in National Parks or National Forests helped lead to the passage of the Weeks Act in 1911, and with that, the Federal Government came to the region as a major holder and manager of land.

|

| Figure 9.—Three sawyers pausing after felling this huge white oak tree and bucking it into mammoth 12-foot logs with a two-man crosscut saw (not visible). A Southern Appalachian forest scene about 1895, indicating the gigantic trees common there before the extensive lumbering activity of the late 1800's. (Photo courtesy of Shelley Mastran Smith) |

The Growth of Logging

The logging industry started gradually, with scattered investments. In the early 1880's Alexander A. Arthur arrived in Newport, Tenn., and purchased 10 square miles of forest land for the Scottish Carolina Timber and Land Co. With funds supplied by backers in Glasgow and in Cape Town, South Africa, he constructed a sawmill at Newport and built a huge boom across the Pigeon River above the town. French Canadian loggers and rivermen came to eastern Tennessee for this enterprise. For 3 years the operation was successful; however, in 1886 a storm flooded the Pigeon River, broke the boom, and swept away a great number of ash, cherry, oak and yellow (tulip) poplar logs, and the company closed for lack of additional capital. [1]

Though this first major venture failed, others were not deterred. H.N. Saxton, an Englishman, organized the Sevierville Lumber Co. in the late 1880's, and later started Saxton and Co., a firm exporting hardwoods to Europe. [2] As the forests of the Northeast and the Great Lakes region were depleted, more and more northern lumber companies came to the Southern Appalachians. Speculators came too, to take advantage of the rich resources and low land costs. Businesses were organized for the explicit purpose of buying land and timber.

In the 1890's the timber speculators began in earnest, and an astonishing number of timber companies moved into the southern mountains. In North Carolina, the Unaka Timber Co. of Knoxville, Tenn., was active in Buncombe, Mitchell, Madison and Yancey Counties, while the Crosby Lumber Co. from Michigan operated in Graham County. In 1894 the Foreign Hardwood Log Co. of New York and the Dickson-Mason Lumber Co. of Illinois made extensive purchases in Swain County. The Tuckaseigie Lumber Co. purchased 75,000 acres of land in Macon, Jackson, and Swain Counties. Other firms included the Toxaway Tanning Co., the Gloucester Lumber Co., the Brevard Tanning Co., the Asheville Lumber and Manufacturing Co., and the Asheville French Broad Lumber Co. After 1900 the Montvale Lumber Co., the Bemis Lumber Co., and the Kitchen Lumber Co. bought large tracts in the North Carolina Great Smokies. The largest North Carolina firms were Champion Fibre Co. which came from Ohio to Canton, N.C., in 1905, and the William Ritter Lumber Co. from West Virginia. The Ritter firm, the largest lumber company in the Southern Appalachians, owned almost 200,000 acres of land in North Carolina alone. [3]

New timber companies also acquired land and timber rights in eastern Kentucky, eastern Tennessee, and northern Georgia. The Burt-Brabb and Swann-Day lumber companies, early developers in eastern Kentucky, were followed by the Kentucky River Hardwood Lumber Co., which at one point owned over 30,000 acres of forest land. Watson G. Caudill operated a lumber company that was active in several counties. However, it was not until the William Ritter Co. moved in that truly extensive and long-term operations began in the eastern counties of the State. The Ritter companies were so large and enterprising that they built their own railroads after the Norfolk and Western Railroad refused to construct lines needed for their business. [4] The Ritter Co. also purchased acreage in the mountains of eastern Tennessee.

The Little River Lumber Co. became a major landowner in the Great Smoky Mountains, with over 86,000 acres near Clingman's Dome. The Norwood Lumber Co., the Vestal Lumber and Manufacturing Co., and the Pennsylvania-based Babcock Lumber Co. also bought land in eastern Tennessee. The Gennett Lumber Co., organized in Nashville in 1901, speculated in land and timber in Tennessee, South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina for most of the 20th century. The Gennett Lumber Co. was one of the most prominent in northern Georgia, along with the Pfister-Vogel Land and Leather Co. of Milwaukee, which actively purchased land there after 1903, for about $2.00 an acre. [5]

|

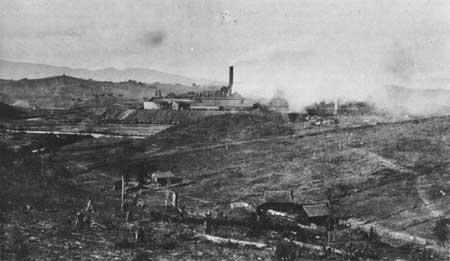

| Figure 10.—Steam engine loading railroad flatcars at log boom on Big Lost Creek, Polk County, southeastern Tennessee, just above Hiwassee River and line of Louisville & Nashville Railroad, near old mill town of Probst, not far from present town of Reliance, in Unicoi Mountains. This area was part of the new Cherokee National Forest Purchase Unit when photo was taken in February 1912. Logs are largely yellow-poplar, which shows good reproduction in this highland region of heavy annual rainfall. Timberlands of the Prendergast Company, which also owned the flatcars and the logging railroad. (National Archives: Record Group 95G-10832A) |

Timberlands Sell Cheaply

Prices paid by the timber companies for land in the southern mountains were astonishingly low. The agents of northern and foreign firms found a people unaccustomed to dealing in cash and unfamiliar with timber and mineral rights and deeds. The companies bought up huge tracts of land for small sums. When local opposition to such purchases began to develop, they switched to buying only timber or coal rights. Some lumber companies even purchased selected trees. The mountaineer, offered more cash than he had seen before in one transaction, found it difficult to refuse an offer, especially since he usually had no idea of the fair value of the land or timber. Enormous yellow- (tulip) poplars and stands of white and red oak and black cherry were sold for 40 to 75 cents a tree. [6]

Ronald D. Eller tells how much Appalachian mountain land was acquired:

The first timber and mineral buyers who rode into the mountains were commonly greeted with hospitality by local residents. Strangers were few in the remote hollows, and a traveler offered the opportunity for conversation and a change from the rhythms of daily life. The land agent's routine was simple. Riding horseback into the countryside he would search the coves and creek banks for valuable timber stands or coal outcroppings, and having found his objective, he would approach the cabin of the unsuspecting farmer. [The farmer's cordial] greeting was usually followed by an invitation to share the family's meal and rude accommodations for the night. After dinner, while entertaining the family with news of the outside world, the traveler would casually produce a bag of coins and offer to purchase a tract of "unused ridgeland" which he had noticed while journeying through the area. Such an offer was hard to refuse in most rural areas, where hard money was scarce, life was difficult, and opportunities few. [7]

Thus the money often provided a welcome opportunity for a family to leave a farm that had been worn out for years. In northern Georgia especially, the farm population was greater than the land could reasonably support, and people sold willingly. [8] In other areas, people were more reluctant to sell to outsiders. Some unscrupulous firms enlisted the aid of local merchants, who would make purchases for "dummy" corporations.

Sometimes land with inexact or missing titles was simply taken from the mountaineers, who often had failed to obtain formal title to their land. This "unclaimed" land could be taken by anyone willing to stake a claim, survey the land, and pay a fee to the State. Other claims were clouded, or not properly surveyed. [9] In some counties, courthouse records had been destroyed by fire, creating uncertainty about ownership. Thus, a timber company could move into an area, conduct its own surveys, and file claim for lands that the mountaineer had long used and thought were his. Litigation was expensive and time-consuming; most residents had neither the sophistication nor the resources to carry a case through court proceedings. In Kentucky, the State legislature passed an act in 1906 that permitted speculators who had held claims and had paid property taxes for 5 years to take such property from previous claimants who had not paid taxes. [10] Thus, rising property taxes created by speculation worked to the advantage of the corporation and against the original claimant, who probably paid low taxes to start with and could not afford an increase. These processes were gradual, but they marked the beginning of the disestablishment of the mountaineer, and further alteration of the mountain economy.

|

| Figure 11—A team of four horses and mules pulling a flatbed wagon carrying a large white oak log to the sawmill along a dirt road near Jonesboro, Washington County, Tenn., in July 1915. Log probably came from Locust Mountain area west of Johnson City, not far from the Unaka National Forest, now a part of the Cherokee. (NA:95G-23262A) |

Timber Cutting Often Delayed

Once the land was acquired, timber companies often did not cut the timber immediately. Most of the Pfister-Vogel lands of northern Georgia were never cut by the firm. The Gennett brothers bought and sold land for decades, cutting over parts, and waiting for good or better lumber prices on others. The Cataloochia Lumber Co. lands in Tennessee were sold to the Pigeon River Lumber Co., and in turn were bought by Champion Lumber Co. The firm of William Whitmer and Sons purchased tracts in North Carolina which it deeded to the Whitmer-Parsons Pulp and Lumber Co., which later sold the lands to the Suncrest Lumber Co., a Whitmer-backed operation. [11]

Other outside firms bought land, timber, or mineral rights for speculation, or for possible use. For example, the Gennetts bought an 11,000-acre tract from the Tennessee Iron and Coal Co.; the Consolidation Coal Co. owned vast tracts in Kentucky, and employed a forester to manage those lands.

At one point, Fordson Coal Co., a subsidiary of the Ford Motor Co. owned about half of Leslie County, Ky., and several land development companies purchased extensively in the mountains of northern Georgia. [12] Such speculation was to inflate the value of all land in the region, as illustrated in the following comments by a Forest Service purchasing agent who came to the Southern Appalachians in 1912:

This is a virgin timber county [the Nantahala purchase area] and about three years ago the big lumber companies, seeing their present supplies in other regions running low, came in here and quietly bought up large "key" areas of timberland. They are now holding these at prices which are more nearly compared with lands in regions where railroad developement [sic] is more favorable . . . The withdrawal of these large bodies has enhanced the value of the smaller tracts . . . [13]

Between 1890 and the First World War, a great deal of timber was cut on purchased lands, and the economic impact was felt throughout the southern mountains. The years 1907 to 1910 were the years of peak activity. Throughout the region, lumber production rose from 800 million board feet in 1899 to over 900 million board feet in 1907. [14] In 1910, the number of lumber mills in Georgia reached almost 2,000; a decade later it had fallen to under 700. Individual tracts yielded vast quantities of lumber: in 1909, one 20,000-acre tract in the Big Sandy Basin produced 40 million board feet of tulip (yellow-) poplar, while in 1912, the mountains around Looking Glass Rock in North Carolina yielded 40,000 board feet of tulip (yellow-) poplar per acre. [15]

Logging Boom Displaces Farmers

The social and economic impact of the logging boom on the peoples of the Southern Appalachians was lasting. For decades small firms and individuals had engaged in selective cutting throughout the region without appreciably changing the economy, the structure of the labor force, or the size of the forests. Now, within a decade or two, the landownership pattern of the southern mountains changed drastically. As mountain lands were sold to the timber interests, farms and settlements were abandoned. As Ron Eller has written:

Whereas mountain society in the 1880's had been characterized by a diffuse pattern of open-country agricultural settlements located primarily in the fertile valleys and plateaus, by the turn of the century the population had begun to shift into non-agricultural areas and to concentrate around centers of industrial growth. [16]

By 1910, vast tracts of mountain land, which had previously been held by privately scattered mountain farmers, had fallen into the hands of absentee landowners, and towns were becoming important centers of population. Although some mountaineers remained on the land as tenants, sharecroppers, caretakers, or squatters, many were displaced.

The changing pattern of landownership was reflected in changes in population and acreage devoted to farming. The population growth of some mountain counties slowed considerably by 1910, and a few actually lost population. For example, Macon and Graham Counties, N.C., which had grown at a rate faster than the State between 1880 and 1900, experienced almost no growth between 1900 and 1910. Over the same decade, Rabun and Union Counties, Ga., lost 11.5 percent and 18.4 percent of their populations respectively. Similarly, both number of farms and farm acreage declined in areas where heavy outside investment had occurred. Between 1900 and 1910, in the counties of extreme northern Georgia, southwestern North Carolina, and southeastern Tennessee, the number of acres in farms dropped roughly 20 percent. In Rabun County, Ga., the number of acres in farms declined 40 percent over the decade. [17]

As the timber companies moved into the region, numerous logging camps and milling towns were established. These centers absorbed the mountain people who had sold their lands, and attracted outsiders eager to benefit from the logging boom. Over 600 company towns are believed to have been established in the southern mountains in 1910, most of which became permanent parts of the landscape. [18] Logging settlements and mill towns circled the Great Smokies: Fontana, Bryson City, and Ravensford, N.C.; Rittertown, Gatlinburg, Elkmont, and Townsend, Tenn. [19] By 1911, Tellico Plains, Tenn., with a population of about 2,000, discovered itself a "busy little city," boosted by the heavy demand for the area's timber. Probably the most famous mill town was Canton, in Haywood County, N.C., created by Champion Fibre Co. In 1905, Champion had bought timberlands along the Pigeon River and built a large flume from the site to the town, about 15 miles away. Carl Schenck wrote about the operation some years later: "At the upper inlet of the flume a snug village with a church and a school was planned. The whole scheme was the most gigantic enterprise which western North Carolina had seen." [20]

Numerous temporary logging camps were established to shelter the thousands of timber company employees. Many of these flourished for several years before being abandoned. Although the lumber companies employed local men, they also imported timber crews from the North and overseas, sometimes hundreds of laborers at one time from their camps in Pennsylvania, New York, or Michigan. A logistical network of support personnel was needed to maintain a lumber camp; thus, building and servicing the camps provided labor for many mountain families. Local men also lived in the logging camps for a few weeks or months at a time while maintaining the family farm. For several years, lumbering provided steady, dependable employment for thousands of mountaineers.

For this reason, although logging helped to disestablish the mountaineer, its social impact was not nearly so destructive as that of coal mining. The southern mountaineer could work in lumbering without relinquishing his life to the company employing him; many of the lumber camps were never intended to be permanent and did not demand that a laborer give up his home for work. Thus,

the immediate effects of lumbering were not especially destructive. In many respects the operations suited already established work habits. Nor were wasteful methods likely to disturb a people who traditionally viewed the forests as a barrier to be destroyed whenever the need for crop land demanded. [21]

Nevertheless, in bringing industrial capitalism and absentee landownership to the Southern Appalachians, the lumber boom altered the region's economy, and made a lasting mark upon its landscape.

|

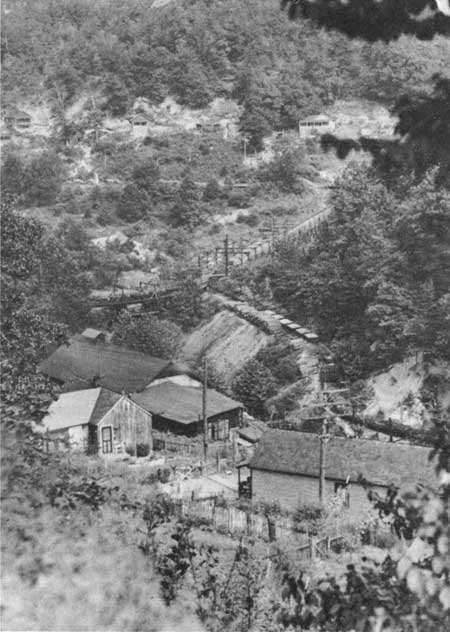

| Figure 12—Barthell Mine of Stearns Coal and Lumber Company at Paunch Creek in Stearns (then Laurel) Ranger District. Daniel Boone (then called Cumberland) National Forest, McCreary County, Ky., in 1940. Note mining camp houses, and stacks of mine props along railroad. (NA:95G-400254) |

Mining Boom Destructive to Land

The penetration of the mountains by railroads was a key unlocking the region's mineral wealth, as it had the region's timber. In McCreary County, Ky., for example,

a virtual wilderness of untouched and unwanted wild lands . . . considered worthless for generations, overnight aroused the interest of the large corporations and land speculators whose agents invaded the territory on the heels of the new railroad . . . [22]

As with timber lands, the sale of mountain lands to coal company agents was usually done willingly, even if unscrupulous methods sometimes were used. In Kentucky, where the Stearns Coal and Lumber Co. bought thousands of homesteads beginning in the late 1890's, William Kinne, the Stearns land agent, was received warmly and came to be regarded with respect and even endearment. [23] Nevertheless, the transfer of landownership to land and development companies in the 1880's and 1890's insured that the control of the mining industry, and much of the profit from it, would flow outside the region.

Mineral developments in the Southern Appalachians included mica, iron, copper, manganese, and coal mining. Mica mining flourished for a time around the turn of the century in North Carolina, and then declined as mica was replaced by other substances. Some mica mining continues, but it is a comparatively small business.

Between the end of the Civil War and about 1910, an iron and copper industry based on locally produced coal, iron ore, copper ore, sulfur, and limestone grew up in eastern Tennessee. Although railroad construction at first improved the market for iron, the expansion of the national transportation network eventually drove the regional producers out of business. Limitations in the quality and quantity of iron ore also were a factor. By World War I, little remained of the iron industry that had flourished earlier in Chattanooga, Ducktown, Rockwood, and Dayton. [24]

In spite of these mineral developments, it is coal mining that most significantly altered the economy and society of the mountains. From 1900 to 1920 the increasing national demand for coal led to the penetration of the Great Lakes market by Southern Appalachian coal producers and to the rapid development and, ultimately, overdevelopment of the mountain coal fields. It was comparatively cheap and easy to extract coal by strip-mining from seams in the mountainsides. The most important requirement was a large supply of cheap labor. [25]

Although large areas of accessible mountain land were affected by the timber boom, coal and other forms of mining at first affected only individual isolated valleys, chiefly in Kentucky and Tennessee. However, the impact of mining was more permanent. Timber companies would "cut and get out," but mining companies, working rich and extensive seams of coal, would remain for years. Unlike the logging camps, the mining towns became of necessity the permanent homes of those who came to work the mines. Mine operators developed company towns partly to provide housing in isolated areas, and partly to gain control of the labor force. Workers often had no alternative to the company town because the coal company owned all the land for miles around.

To the coal entrepreneur, a local mountaineer who remained on his own "home place" was an unreliable worker. He would take time off for spring planting, and several times a year he would go hunting. He might also take off from work for a funeral or a family reunion. Once a worker was housed in the company town, however, he could be disciplined more effectively because, if he lost his job in the mine, he would be evicted from his house at the same time. Also, most company towns did not permit independent stores to operate. Workers were generally in debt for purchases made at the company-owned store. In many towns even a garden patch to supplement the store-bought food was, for lack of space, impossible.

When the timber boom began to slacken just after World War I, mountaineers who had been dependent on work in the logging camps and sawmills moved into the coal mining areas of the mountains to find work. Many went across the crest of the Appalachians from North Carolina and Virginia into Kentucky to the coalfields of the Cumberlands. Mountaineers were also faced with competition for jobs, when outsiders, including blacks from the Deep South, as well as European immigrants, were imported to enlarge the labor force.

|

| Figure 13.—"Spoil banks" of raw acid subsoil, left over from strip-mining of shallow seams of soft coal 5 years earlier. McCreary County, Ky., Daniel Boone (then Cumberland) National Forest, July 1955. (Forest Service photo F-478950). |

Squalid Company Towns

The coal industry in the Southern Appalachians continued to grow until 1923. However, throughout the 1920's the coal producers maintained their competitive advantage by wage reductions. The cut-throat competition in the coal industry discouraged investment in improvements for the company towns. Many of these hastily constructed communities grew increasingly squalid. Miners moved frequently, hoping for better housing and working conditions at another mine.

Mining was destructive to the environment, even in the early days. The demand for pit props, poles, and railroad ties contributed to the exploitation of the surrounding forests. The mines produced slag heaps and acid mine runoff which severely damaged streams and wildlife. The company towns had no facilities for sewage and refuse disposal, so human waste and trash heaps polluted the creeks, causing serious health hazards. One particularly blighted area, perhaps the largest and most notorious in the United States, was near Ducktown, Polk County, Tenn., and McCaysville, Fannin County, Ga. There, the acid fumes from the smelting and refining of copper and iron had destroyed thousands of acres of the mountains' entire vegetative cover. Erosion was severe from the bare slopes, and heavy silting occurred in the main channel of the Tennessee River, 45 miles to the west. [26] Yet decades went by before such devastating impacts of mining attracted wide attention.

The impact of largescale logging on the Southern Appalachians in the years after 1890 was not only economic and social. It encouraged fires, erosion, and floods that drew national attention to the region and sparked legislation authorizing most of the eastern National Forests.

In terms of both investment and impact, logging operations in the mountains actually occurred in two phases. The first, roughly from 1880 to 1900, was characterized by low investment, "selective" cutting (usually "high-grading"), and a spatial separation between timbering operations and milling. The second phase, beginning around 1900, peaking in 1909, and lasting into the 1920's, involved a higher level of investment, heavy cutting, and the construction of rail lines and mills throughout the mountain forests. It was with the latter stage that environmental damage became acute.

In the early days, only the largest and highest quality trees were cut: cherry, ash, walnut, oak, and yellow- (tulip) poplar, often as large as 25 feet in circumference. Although it is difficult to imagine today, trees were felled that were larger in diameter than an average man stands. Some portable sawmills were brought into the mountains in the earlier years, but logs from these enormous trees were usually transported to a mill, some miles distant, by horse, oxen, or water. Typically, log splash dams were built on the shallow mountain streams so that many logs could be moved at one time. Logs were rolled into the lakes formed behind the dams, and with a buildup from rain or melting snow, the dams were opened to let the logs cascade down the mountains. From wider places on the river, trees—as many as 40 to 120 at a time—were lashed together to form rafts, which were piloted downriver to the mills. [27]

Elbert Herald reminisced about this kind of logging for the compilers of Our Appalachia. As a boy, Herald logged with his father in Leslie County, Ky., between 1922 and 1930. His experiences are typical of the small local lumbering operations that went on before, during, and after the big timber boom.

I was eleven years old when I moved to Leslie County. It was a very isolated country up there, mind you, I said this was in 1922: there was not one foot of highway, there was not one foot of railroad. My father, he looked around and there was plenty of hard work to get done, and we went to work cutting logs.

There wasn't any saw mill around to sell them at closer than Beattyville, a right smart piece away. There was a number of companies we would contact [to] get a contract for so many logs . . .

Walnut and white oak at that time was best. We would get $35 a thousand [board feet] for that, but when it come down to beech and smaller grades we done well to get $25 a thousand.

[We] cut roads through the hills and hauled our logs down to the riverbanks with work oxens and horses. When we got [the logs] to the river we would raft them together and buyers would come along buying. If it was real big logs—anywhere from 24 to 28 inches [in diameter]—we would take about 65 logs. If they were smaller logs—anywhere from 18 to 22 inches—we'd take 75 or 80 on a raft, which would amount to anywhere from 8 to 10 thousand board feet, depending on the length of the logs. [28]

Although logging was hard work and timber prices were not high, Herald explained that it was the only way to make money at that time. The market for farm crops was dismal.

Although this kind of logging was careless and destructive, its environmental impact was minor compared to the intense logging of the boom period. Small local lumber operations cut trees very selectively, according to size, quality, and proximity to a stream. Relatively few men were engaged in lumbering at first, and the visible effects of milling were scattered and removed from the source of supply. It had been estimated that even in 1900 most of the area was wooded and at least 10 percent of the Southern Appalachian region remained in virgin timber. [29]

Before that year, however, distinct changes began. Out-of-state and foreign investors began purchasing large tracts of mountain land, and rail lines were built into previously inaccessible valleys. With railroads, mills could be located close to the source of supply; trees had to be transported only short distances, and finished lumber could be carried to the market.

One of the most impressive railroad projects in the mountains was that of the Little River Lumber Co. Chartered in 1901, the Little River Railroad was a standard-gauge line from Maryville, Tenn., at the southwestern corner of the Great Smokies, to the mill at Townsend, then running 18 miles up the gorge of the Little River to the base of the timber operations. The rail construction greatly increased the ease and scale of operations. By 1905, the mill was cutting about 60,000 board feet of wood per day. This area is now well inside the Park, not far from the cross-Park highway, U.S. Route 441.

Other methods, too, were devised to further largescale tree removal; among them were inclined railways controlled by yarding machines, and overhead cable systems, both used with considerable success in the Smokies. [30] To facilitate log transportation, larger flumes and splash dams were built. A concrete splash dam built across the Big Sandy River in Dickenson County, Va., was probably the largest. Completed in 1909, it was about 360 feet high and 240 feet across, with five flumes, each 40 feet wide, through which the pent-up logs tumbled. [31] The dam enabled the Yellow Poplar Lumber Co. to run logs to Cattletsburg, Ky.,in record time; within 10 years, the merchantable hardwood timber supply of the Big Sandy Basin had been virtually exhausted.

|

| Figure 14.—Smelter of Tennessee Copper Company at Copper Hill-McCaysville on Tennessee-Georgia State line in Southern Appalachian Highlands along Ocoee River. When photo was taken in September 1905, plant was undergoing great expansion. Forest devestation from sulfur fumes of smokestacks was already evident. Area is near the edges of three National Forests and three States. Acid fumes from this and other smelters in the "Copper Basin" destroyed timber and wildlife on thousands of acres of forests and caused severe soil erosion for many years, muddying waters of the Tennessee River, more than 40 miles distant, before operations ceased. (NA:95G-63040). |

Wasteful Cutting Damages

Forests

Throughout the region, as the scale of logging increased, size selectivity in cutting declined:

The depletion of the forests is revealed by the rapidly changing cutting standards as culling became the rule rather than the exception. In 1885 few logs under 30 inches in diameter were cut. Ten years later the usual cutting was 24 inches. By 1900 the average limit had dropped to 21 inches. By 1905 lumberman were taking chestnut and oak only 15 inches on the stump. [32]

Not only was there a decline in the average size cut, there was a shift as well in the species of trees harvested. As the best cherry, ash, and oak were depleted, the demand for hemlock and spruce grew. Both were used for pulpwood in the manufacture of paper products, and during World War I spruce was used to build the first fighter airplanes. Chestnut, which the leather goods industry had used profitably for its byproduct, tannin, came into increasing demand when a process was developed by Omega Carr to manufacture pulp from chestnut chips, once the tannin was removed. The Champion Paper and Fibre Co., mill in Canton, N.C., became a major producer of pulp from chestnut wood—until this source disappeared after the chestnut blight reached the area in 1920.

Throughout the logging boom, trees were harvested with little regard for other resources or future timber supplies. Young growth was damaged and smaller limbs and brush were left to ignite untended in dry spells, destroying the humus and remaining ground cover, preventing absorption of rain and snow. In areas of heavy logging, particularly on steep slopes, the soil became leached and erosion was often severe.

|

| Figure 15—Steam overhead cable skidder on rails bringing in logs from two facing slopes on tract of Little River Lumber Company in Great Smoky Mountains, Sevier County, Tenn., in 1913. (NA:95G-15507A) |

It is difficult, if not impossible, to assess the amount or lasting effects of this damage. Even at its peak, the timber industry left large sections of remote mountain forests little touched. [33] Parts of the Great Smokies, and much of far southwestern North Carolina (later the Nantahala National Forest) remained in "virgin" timber. However, in more accessible mountain regions—southern Union, Fannin, and Rabun counties, Ga.; northeastern Tennessee; near Mt. Mitchell and Asheville, N.C.,—whole mountainsides were cut over and burned, hillsides were eroded, and dried-up autumn streams became raging rivers in the spring.

Such conditions came to national attention shortly after the turn of the century. In 1900, the Division of Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture, in cooperation with the Geological Survey, U.S. Department of the Interior, conducted a field investigation of the Southern Appalachian region. The survey results, sent to Congress by President Theodore Roosevelt 2 years later, decried the widespread damage, and attributed the land conditions to poor farming practices, repeated fires, and destructive lumbering:

In these operations there has naturally been no thought for the future. Trees have been cut so as to fall along the line of least resistance regardless of what they crush. Their tops and branches, instead of being piled in such way and burned at such time as would do the least harm, are left scattered among the adjacent growth to burn when driest, and thus destroy or injure everything within reach. The home and permanent interests of the lumberman are generally in another state or region, and his interests in these mountains begins and ends with the hope of profit. [34]

Such conditions supported the survey report's conclusion that a Federal forest reserve in the Southern Appalachians was the only way to stop the continuing losses.

|

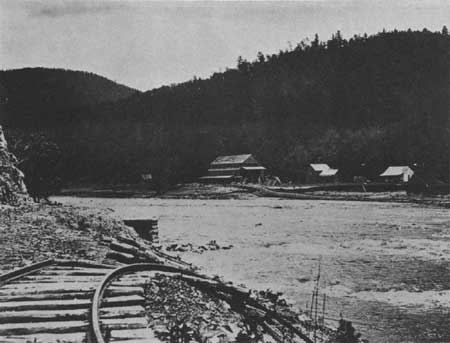

| Figure 16—Railroad bridge washed out over the Nolichucky River at Unaka Springs, Tenn., after flood of May 21, 1901. Such floods stimulated strong public demands early in this century for national parks and forests in the Southern Appalachians. Forests in this area became part of Unaka National Forest in 1921, later the Unaka District of Cherokee National Forest. (NA:95G-11062) |

American Forestry Begins In

Appalachia

This indiscriminate but profitable logging exploitation of the mountain forests was soon challenged by a conservative approach. In 1892, amidst the timber boom, America's first experiment in practical forestry began in the Blue Ridge Mountains of western North Carolina.

Practical forestry was a vital part of the general conservation movement that arose in the United States in the last quarter of the 19th century and reached its peak during the presidency of the Progressive, Theodore Roosevelt. An intellectual and political phenomenon, the conservation movement was largely a response to the rapid industrialization and urbanization after the Civil War. Settlements had extended across the continent, the landscape had been altered, and American culture appeared increasingly materialistic. A countermovement developed to preserve pristine areas and to try to conserve the Nation's natural resources for present and future generations. As with the Progressive movement in general, conservation concerns were expressed essentially by urban dwellers and Easterners. The focus of conservation attention, however, was primarily in the West, where vast extents of land remained in the public domain and where large tracts of forest remained in "virgin" timber. [35]

The conservation movement embodied two distinct groups: preservationist and utilitarian. The preservationists, inspired by Henry Thoreau and exemplified by the influential founder of the Sierra Club, John Muir, believed in saving as much as possible of the Nation's scenic wilderness and forest expanses just as they were—never to be exploited by humans. They believed the beauty of the natural landscape should be valued in and of itself. The creation of Yellowstone, the first National Park, in 1872, was one of the earliest outgrowths of such concerns. [36]

In the last four decades of the 19th century a second conservationist faction developed: those who believed that renewable resources should be protected and managed through wise and economical use. The principal focus of this philosophy was the Nation's forests where the mechanics of economical conservation were to be demonstrated. A leading spokesman for this philosophy was Gifford Pinchot, early forester, who became Chief of the USDA Division of Forestry in 1898 and of its successor, the Forest Service, in 1905.

|

| Figure 17.—Severely eroded steep rocky slope, the result of bad crop farming, along Scotts Creek, Jackson County, west of Asheville, N.C., after heavy rains of May 21, 1901. Scattered hardwoods and pitch pine are visible on hillside. (NA:95G-23515). |

Forest Reserves Authorized in

1891

Between 1890 and 1910, practical-conservationist concerns were translated into political action. In 1891 by an amendment to the General Land Law Revision Act, often called the Creative Act, Congress gave the President almost unlimited power to withdraw huge expanses of forested lands from the public domain. In 1897 an amendment to the Civil Appropriations Act, often called the Organic Administration Act, established the management objectives of these reserves: ". . . securing favorable conditions of water flow and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States." [37] Timber in forest reserves was to be harvested and sold; waters could be used for mining, milling, or irrigation.

Before the passage of the Weeks Act in 1911, numerous large forest reserves were set aside in the West from lands in the public domain. It was in the East, however, where practical forestry was inaugurated. At Biltmore, between 1890 and 1910, the foundations were laid for scientific forestry as the Nation was later to practice it; here too some experiences and problems with the local population and commercial interests foreshadowed those of the first Federal foresters.

In 1889, the wealthy George W. Vanderbilt of New York, who had previously visited the area as a tourist, purchased about 300 acres of small farms and cutover woodlands near the French Broad River southwest of Asheville. The tract was composed of "some fifty decrepit farms and some ten country places heretofore owned by impoverished southern landed aristocracy." [38] The lands were in poor condition, having been abused by cutting, fires, erosion, and neglect. There Vanderbilt began construction of the palatial Biltmore House, and acquisition of what was to become a 100,000-acre estate. Over the next two decades Vanderbilt established an English-style village, an arboretum, parks, a wildlife preserve stocked with deer and pheasant, ponds and lagoons, a dairy farm, and miles of roads and trails as part of a vast experiment in landscape alteration. [39]

Vanderbilt's land-management philosophy was ahead of its time. His goal was to recultivate the fields and rebuild the forests with the most scientifically advanced methods of the day; Biltmore was to be a model of dairying, horticulture, landscaping esthetics, wildlife management, and productive forestry. In 1892, upon the recommendation of the famous landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmstead, creator of Central Park, New York City, who was in charge of landscaping the Biltmore grounds, Vanderbilt hired Gifford Pinchot, the future Chief of the Forest Service, to supervise Biltmore's forest lands.

Pinchot was at Biltmore for 3 years. During that time he conducted a survey and inventory of the more than 7,000 acres that had been acquired; continued management of the Biltmore Arboretum (an experimental garden with over 100 species of trees); continued the reforestation of badly cutover and eroded areas on the estate; and supervised the purchase of mountain lands to the west which came to be known as Pisgah Forest. There, in the fall of 1895, Pinchot directed the first logging of yellow- (tulip) poplar. To disprove the local notion that once such a forest was felled, it would never grow back, Pinchot cut selectively in the Big Creek valley below Mt. Pisgah only those large trees he had chosen and marked—felling, bucking, and hauling the logs out carefully so as to avoid damaging young trees. Although he claimed to know "little more about the conditions necessary for reproducing Yellow poplar than a frog knows about football," he understood that it needs strong light to grow well and that creating openings in the forest by felling mature trees would encourage a new crop. [40] Although the immediate goal was profit, the long-range objective was to preserve the remaining stand and insure a steady annual yield. Pinchot claimed his lumbering to be profitable, rather unconvincingly, since Vanderbilt himself consumed most of the timber. [41]

Pinchot left Biltmore in 1895; he had gradually become disappointed and disillusioned with Vanderbilt's motivations, and was ambitious for new experiences. Replacing Pinchot was Carl Alwin Schenck, a young highly recommended German forester, who for 14 years carried on and intensified Pinchot's efforts. He continued the practice of selective lumbering, and intensified reforestation efforts throughout the Vanderbilt estate. Schenck initially experimented with hardwood plantings, but eventually concentrated on reforestation of culled and eroded areas with eastern white, pitch, and shortleaf pines. [42]

|

| Figure 18.—Enormous load of gravel and silt deposited on 20-acre field on farm of William Brown along Catawba River, McDowell County, above Marion, N.C., by floods of May 21 and August 6, 1901. This area borders the present Pisgah National Forest. (NA:95G-23325). |

Early Forestry School at

Biltmore

Schenck carried out one of Pinchot's recommendations by establishing in 1898 the Biltmore School of Forestry in Pisgah Forest, now the site of the Forest Service's Cradle of Forestry historical exhibit. There, Schenck personally trained young men in all aspects of practical and textbook forestry, from seedlings to sawmilling. Although most went into industrial forestry, many became State and Federal foresters. Among his graduates were several leaders of the early Forest Service, including Overton W. Price, Associate Forester under Pinchot, Inman F. Eldredge, who supervised the first Forest Survey of the South, and Verne Rhoades, first supervisor of Pisgah National Forest. [43]

Although both Schenck and Pinchot believed in the wise utilization of resources as opposed to strict preservation, Schenck ran his school under a philosophy slightly different from Pinchot's. Schenck alternated book learning with practical experience in the woods, and was more interested than Pinchot in the hard economics of forestry. Over the years, the two men, both with very strong viewpoints and personalities, bickered continuously, sometimes bitterly. In essence, Pinchot separated forestry from sawmilling; Schenck did not. His frequently quoted dictum, "That forestry is best which pays best" indicates Schenck's orientation to industry. [44] He felt Pinchot's silvicultural practice of selective cutting to be a luxury that market prices or financial pressures often did not allow. This remains a debated issue today. Schenck wrote that Pinchot was furious "When he learned that in the school examinations at Biltmore a knowledge of logging and lumbering was weighed higher than that of silviculture or of any other branch of 'scientific' forestry . . . ." [45]

|

| Figure 19.—Cane creek at Bakersville, Mitchell County, N.C., showing broad heavy deposit of silt from flood of May 21, 1901. Seven of the houses at right were washed away or badly damaged. The flood aroused wide interest in a Federal Forest Reserve. This area borders the present Pisgah National Forest. (NA:95G-25369) |

Although Schenck was more commercially oriented than Pinchot, he too was frequently frustrated with the local inhabitants of the French Broad area. The Vanderbilt estate, including Pisgah Forest, was dotted with many small inholdings, as it still was when the Federal Government purchased it in 1914. In spite of Vanderbilt ownership, the indwellers continued to use the land as if it were theirs; they cut wood, farmed, grazed cattle, and hunted freely on Vanderbilt land. Schenck considered this trespassing a serious block to his forestry efforts:

In the Southernmost part of Pisgah Forest the size and the number of the interior holdings were so great that Vanderbilt's property in the aggregate was smaller than that of the holders. The woods in my charge were on the ridges and on the slopes above the farms where there was no yellow poplar. Mine seemed a hopeless task. For years to come, I could not think of conservative forestry. [46]

Throughout his service with Vanderbilt, Schenck continued to urge acquisition and consolidation of the inholdings, with some success.

In addition to trespassing, Schenck was frustrated with the mountaineers' penchant for burning to "green up" the pastures and clear the brush, and remained incredulous that no local regulations existed to prevent or control fire:

The citizens of the county do not realize—do not want to realize—that my work is for their benefit as well as for that of my employer. We have never found any encouragement whatsoever in our work on the side of the state, the county, or the town. We are aliens; we do things out of the ordinary; that is cause enough for suspicion—for antagonism and enmity. [47]

These sentiments were echoed a decade later by some of the first Federal foresters in the region. And the two major concerns of Schenck—trespass and fire—continue to occupy the foresters in the Southern Appalachians today.

Although the local population remained a problem for Schenck, he was to have a positive and notable impact on industrial forestry throughout the region. Schenck was well known and respected by several local industrialists, who sought his advice on reforestation and marketing. The St. Bernard Mining Co. of Earlington, Ky., for example, experimented extensively before 1909 with hardwood plantings on lands no longer valuable for farming, and communicated with Schenck for guidance and expertise. [48]

|

| Figure 20.—Schenck Lodge, built in Black-Forest-of-Germany style on site of old Biltmore Forest School, now the Cradle of Forestry Visitors Center, Pisgah National Forest, Brevard, N.C., as it appeared in August 1949. Lodge had just been restored with new roof and foundation. It was originally built to house forest workers on the old Biltmore Forest, and then to house students in Dr. Carl A. Schenck's school, It is now used for administration and public recreation. (Forest Service photo F-458641) |

Schenck's influence on industrial forestry was most noteworthy, however, in his association with the Champion Fibre Co. In 1906 Champion's president, Peter G. Thompson, came to North Carolina from Hamilton, Ohio, to buy spruce acreage in the Great Smoky and Balsam Mountains for making pulp. In 1907, Reuben B. Robertson, Thompson's son-in-law, opened the Champion Paper and Fibre Co. at Canton, N.C. Both men became well acquainted with Schenck. Although Schenck was never able to convince Thompson of the value of second-growth planting, he had more success with Robertson. Through Schenck, Robertson became convinced of the advantages of sustained-yield forestry, and earned Champion a reputation for intelligent, conservative lumbering. In 1920, Champion employed Walter Darntoft as corporate forester—the first such industrial forester in the South. [49]

|

| Figure 21 —Replica of original Biltmore Forest School building on Pisgah National Forest, Brevard, N.C., south of Asheville, now part of the Forest Service's Cradle of Forestry Visitor Center. Photo was taken in August 1967, a year after reconstruction. (Forest Service photo F-516882) |

The Move For Eastern Reserves

The Southern Appalachians gradually became a focus for the conservation movement. In addition to the forestry experiment at Biltmore, efforts began in western North Carolina to create an Appalachian National Park, largely through the Appalachian National Park Association, led by Dr. Chase P. Ambler of Asheville. Ambler, who had come from Ohio as a specialist in treating tuberculosis, valued the area's scenery and climate for what he considered its restorative characteristics. [50] The original sentiment behind the Association was preservationist: that the beauty and healthfulness of the Southern mountains should be preserved from destructive logging for the pleasure of future generations; the idea was to create an eastern equivalent of Yellowstone. [51] Within 2 years, however, the concern for scenic preservation was supplanted by the drive to create a forest reserve, and the interests of the park enthusiasts and foresters became temporarily commingled.

Through the lobbying effort of Dr. Ambler's group and the sponsorship of North Carolina Senator Jeter C. Pritchard, in 1900 Congress appropriated $5,000 for a preliminary investigation of forest conditions in the Southern Appalachians. The investigation, conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture with the help of the U.S. Geological Survey, also considered farmlands and the flow of streams throughout the region. Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson and Gifford Pinchot, at that time Chief of the USDA Division of Forestry, spent about ten days looking over the region themselves.

The report of the survey, published in 1902, details the land abuses of the Southern Appalachian region. Its tone is reminiscent of George Perkins Marsh's Man and Nature, the classic conservationist volume first published in 1864, with which Pinchot was very familiar. [52] Marsh's repeatedly stated theme was that man's influence on the land—particularly in clearing and burning forests and overgrazing pastures—had been detrimental and destructive. The message of the Southern Appalachian survey report, with pictures to support each point, was essentially the same: the special hardwood forests of the beautiful Appalachians were being destroyed by lumbering, fires, and—perhaps worst—by mountainside farming. These agents of destruction were causing the soil to leach, slopes to erode, and streams to flood their banks with rain and melting snow. The only clear solution: "for the Federal Government to purchase these forest-covered mountain slopes and make them into a national forest reserve." [53]

Throughout the decade of 1900 to 1910, the movement to create an Appalachian Forest Reserve grew in the size and diversity of its support to become a powerful and effective lobby group. In 1902 the National Hardwood Lumber Association and the National Lumber Manufacturers' Association passed resolutions favoring a Southern Appalachian Forest Reserve. Although many small mill operators and independent lumbermen continued to oppose the reserve movement, some of the largest firms, once assured that logging would continue, welcomed Federal land purchase as a relief from taxes on cutover useless land and an assurance of support for sound forestry. [54] In 1905, the movement gained the strong and broad-based support of the American Forestry Association, calling for Forest Reserves in both the Southern Appalachians and White Mountains. Indeed, when the AFA endorsed the Appalachian reserves, Ambler and his group disbanded and turned their efforts over to the more vigorous, nationally based association.

Throughout the decade nearly 50 bills to authorize an Appalachian Forest Reserve—or eastern reserves—were introduced in Congress. At first, Congressional opposition to the idea was strong, based on the issue of States' rights. This opposition was overcome in 1901 when the legislatures of North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and Virginia approved the Federal Government's right to acquire title to land in their States, and relinquished the right to tax that land. The Federal Government's constitutional authority to acquire land for reserves continued to be questioned, however, until the linkage was made between such acquisition and the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce. The theory ran as follows: Removal of the forest cover affects streams flooding to such an extent that navigation is threatened; restoration of the forest will assure stream control, and hence navigation.

This linkage, however, was difficult to establish: in 1900 there was considerable doubt as to whether forests really did help control stream flow. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers denied it. Indeed, there was disagreement within the Forest Service itself over the issue. Both Bernhard E. Fernow, Pinchot's predecessor as Chief of the Division of Forestry, and William B. Greeley, then Forest Assistant and later Forest Service Chief, believed that the effects of a forest cover on waterflow were often exaggerated, and questioned the extent to which forests could actually prevent floods. Even Pinchot acknowledged that the role of ground cover could be overestimated. Nevertheless, these internal doubts were suppressed, and the Forest Service adopted a position of aloofness in the ensuing public debate. [55]

Meanwhile, reserve proponents went to considerable pains to convince skeptical Congressmen that a cause and effect relationship existed between forests and floods. In May 1902, for example, representatives of Ambler's Appalachian National Park Association (soon renamed Appalachian Forest Reserve Association) took two miniature mountains which they had built to a Washington meeting with the House Agriculture Committee.

These model mountains were about six feet high and were built on a slope of thirty degrees, being constructed on frames. The one miniature mountain was left bare, the gulleys and depressions in the sides of the mountain being faithfully reproduced. The other mountain was covered with a layer of sponge about four inches thick and over this was spread moss; in this moss were put small twigs of evergreens. The Committee on Agriculture admitted that we had two very good illustrations of mountains.

Rain was caused to fall on these mountains by a member of the association climbing a step ladder with a sprinkling can, endeavoring to demonstrate what occurred when it rained on the forest covered mountain and bare mountains. The results were that the demonstration showed conclusively that the water which fell on the bare mountain ran off with a gush, forcing rivers in the lowlands out of their banks and causing devastating floods; while the rain which fell on the forest covered mountains was held in the humus and given up slowly in the form of springs, thus regulating the water supply in the lowlands.5 [56]

Most Congressmen remained unconvinced. In addition, legislators from the West and Midwest, particularly Speaker of the House Joseph G. ("Uncle Joe") Cannon of Illinois, were antagonistic toward the idea of eastern reserves, and some were resentful of the Pinchot-engineered transfer of the Forest Reserves from the Department of Interior to the Department of Agriculture early in 1905.

|

| Figure 22—New Visitor Information Center at "Cradle of Forestry," Pisgah National Forest, Brevard, N.C., August 1967. (Forest Service photo F-516886) |

Severe Floods Trigger Weeks Act

The eventual success of the legislation for eastern Forest Reserves with the passage of the Weeks Act in 1911 can be attributed to two factors. First, the Weeks Act was the result of persistent, insistent lobbying. Absolutely convinced of the rightness of their cause, the Forest Reserve proponents gradually won broader and broader support, and outlasted the opposition. Second, physical events reinforced their arguments. In 1907 disastrous and costly flooding which occurred along the Monongahela and Ohio Rivers was traced directly to the cutover conditions of the upper watershed. In 1910 a series of mammoth, disastrous fires swept the Northwest, particularly Montana and Idaho. These environmental cataclysms helped persuade legislators that the destructive logging of the past two decades was taking its toll, and that forests had to be better managed for fire controls. [57] The combining of these two interests helped to ease passage of the Act, eventually resulting in establishment of National Forests in Pennsylvania and West Virginia at the headwaters of the rivers flooded in 1907. [58]

After a final 2 years of intense debate but waning opposition the Senate passed a bill on February 5, 1911, that the House had approved in June 1910, to allow creation of Forest Reserves in the East, by purchase. The bill was known as the Weeks Act after John Weeks, Congressman from Massachusetts and member of the House Committee on Agriculture, who had been the bill's sponsor for several years. [59] Based on the authority of Congress to regulate interstate commerce, the bill authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to examine and recommend for purchase "such forested, cut over, or denuded lands within the watersheds of navigable streams as in his judgment may be necessary to the regulation of the flow of navigable streams . . ." An initial $11 million was appropriated to cover the first several years of purchase. The bill created the National Forest Reservation Commission to consider, approve, and determine the price of such lands. The Commission, which was to report annually to Congress, was composed of the Secretary of the Army, Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of Agriculture, two members of the Senate selected by the President of the Senate, and two members of the House appointed by the Speaker. In addition, the bill authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to cooperate with States situated on watersheds of navigable rivers in the "organization and maintenance of a system of fire protection" on private or State forest land, provided the State had a fire-protection law.

Although the Weeks Act did not specify the Southern Appalachians or the White Mountains as areas of purchase, it was implicitly directed at those watersheds. Lands whose purchase was necessary for stream regulation were in rugged mountainous areas of heavy rainfall where the absence of a forest cover would threaten stream regularity and, hence, navigability. Having studied these lands for the last decade, the Forest Service knew in 1911 the general acreage it wanted to acquire. As soon as the Weeks Act passed, Forest Service Chief Henry Graves, Pinchot's successor, assigned 35 men to the task of examining the designated areas.

It is difficult to gauge precisely the involvement of the people of the Southern Appalachians in the Forest Reserve movement or to assess the impact on them of the growing national interest in their area. Certainly, the organized movement for an Appalachian National Park, and subsequently a forest reserve, was never very large. The original size of the Appalachian National Park Association membership was 42, composed principally of professionals: doctors, attorneys, editors, geologists among them. [60] The total membership in 1905 was 307, with more members living outside North Carolina than within the State. [61] Although the geographical base of the group's membership had broadened, it is unlikely that the occupational base had. Thus, the group of local, active supporters for a park or Forest Reserve remained small, essentially urban, and—in a sense—elitist.

The degree of local general awareness of the Forest Reserve movement is difficult to assess. Certainly, the publicity campaign of Appalachian National Park-Forest Reserve Association was earnest: Dr. Ambler and others, such as Joseph Holmes and Joseph Pratt of the North Carolina Geological Survey, spoke throughout the State and before Congress in support of the proposed reserve. Local and national newspapers favorably addressed the issue. However, the extent to which this publicity reached the mountain populace is uncertain. There were signs of local opposition to the forest movement, primarily from the smaller, independent lumbermen, some of whom were undoubtedly misinformed or confused about the purpose of such reserves, some of whom simply resented a Federal intrusion. For example, some lumber interests circulated erroneous information about the reserves, which was countered by editorials in the Asheville Citizen. [62] Inman Eldredge, a graduate of Biltmore Forest School who was with the Forest Service in the South from the earliest days, has spoken of the "murky atmosphere of animosity" between lumbermen and Pinchot's foresters in the years before the Weeks Act.

It is probably safe to say that the majority of the local population was oblivious or indifferent both to the Forest Reserve movement and the opposition to it. As Forester Eldredge expressed it:

. . . All the rest of the people didn't know and didn't give a damn. Forestry was as odd and strange to them as chiropody or ceramics. The people right down on the ground, the settlers, the people who lived in the woods . . . were completely uninformed and were the greatest, ablest, and most energetic set of wood-burners that any foresters have had to contend with. [63]

|

| Figure 23—Forest Service ranger making camp at day's end. Pisgah National Forest, N.C., June 1923. (NA:95G-176512) |

The Early Forest Service

The Forest Service in 1911 was a very young and, at that time, threatened organization. Gifford Pinchot, who had been Chief Forester with the Department of Agriculture since 1898, had been fired by President Taft in January 1910 for his insubordination and highhandedness in challenging the policies of the recently appointed Interior Secretary, Richard A. Ballinger. Early in 1905, Pinchot had engineered the transfer of the Forest Reserves from the General Land Office of the Department of Interior to the Bureau of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. He had virtually created the Forest Service. Having united in one office the functions of overseeing forest reserves and advising the Nation on forestry, Pinchot was beginning to achieve his goals:

. . . to practice Forestry instead of merely preaching it. We wanted to prove that Forestry was something more than a subject of conversation. We wanted to demonstrate that Forestry could be taken out of the office into the woods, and made to yield satisfactory returns on the timberland investment—that Forestry was good business and could actually be made to pay. [64]

Unfortunately, although he had had strong support from President Roosevelt, Pinchot created enemies in his intense conservation campaigns. When Taft succeeded Roosevelt early in 1909, he allowed Pinchot to remain Forest Service Chief, but Taft's appointments and policies were soon intolerable to Pinchot. Less than a year later, as a result of Pinchot's public attacks on Ballinger, Taft was forced to remove Pinchot.

Henry Graves, Dean of the Yale School of Forestry, was named to replace Pinchot in January 1910, probably through Pinchot's maneuvering. [65] A serious, studious, no-nonsense administrator, Graves presented to many a needed contrast to the flamboyant, aggressive, self-righteous Pinchot. In 1910 the Forest Service was not in Congressional favor, and thus needed an economy-minded, moderate, apolitical leader.

The frugality imposed on the Forest Service during Graves administration compounded the already demanding, self-sacrificing existence that Forest Service employees were expected to assume in those early years. Pinchot's original "Use Book," The Use of the National Forest Reserves, published in 1905, leaves little doubt as to the rigorous eligibility requirements of a ranger:

To be eligible as ranger of any grade the applicant must be, first of all, thoroughly sound and able-bodied, capable of enduring hardships and of performing severe labor under trying conditions. Invalids seeking light out-of-door employment need not apply. No one may expect to pass the examination who is not already able to take care of himself and his horses in regions remote from settlement and supplies. He must be able to build trails and cabins and to pack in provisions without assistance. He must know something of surveying, estimating, and scaling timber, lumbering, and the livestock business . . . Thorough familiarity with the region in which he seeks employment, including its geography and its forest and industrial conditions, is usually demanded . . . [66]

Although these words were softened slightly during Graves' administration, their tone continued to stress that Forest Service employment was only for those with special qualifications.

By 1915 the basic areas of Forest Service activities had evolved as three distinct organizational units: the National Forests, cooperation with States and private owners, and forestry research. [67] Forest administration was decentralized, with forests grouped into major Districts under largely independent District Foresters. (Districts became Regions in 1930.) A supervisor was responsible for each forest, and rangers were in charge of the administrative districts within the forests. Other Forest Service officers included deputy supervisors, forest examiners, forest assistants, lumbermen, and scalers. All were appointed after a Civil Service examination.

The district ranger, then as now a crucial position in the Forest Service field organization, was charged with the management of timber sales, grazing, fire protection, and special uses for about 60,000 acres, on the average, at that time. In 1915 he was paid an annual salary of between $900 to $1,200. By 1920 that salary had barely increased; forest supervisors were paid only twice that. Indeed, the continuing low salary caused a sizeable defection in the Forest Service technical staff between 1918 and 1920. [68]

Rangers were required to pass both a written and a field examination, the latter a test of various practical skills including lumbering, horsemanship, and surveying. Clyne and Walter Woody of Suches, Ga., whose father, W. Arthur Woody, became a U.S. forest ranger in northern Georgia in 1918, remember that the examination lasted for several days and was extremely demanding in the endurance and range of skills required. [69] W. Arthur Woody, who later became one of the most well-known rangers, was a native of the mountains who proved invaluable because of his devotion to conservation and the respect he had among the mountain people.

Even in the earliest days, the relationship between Forest Service officers and the general public was regarded as important. According to the 1915 Use Book, Forest Service personnel were not just officers of the Government, but "also agents of the people, with whom they come into close relations, both officially and as neighbors and fellow citizens." Thus, they were encouraged to be "prompt, active, and courteous in the conduct of Forest business" and "to prevent misunderstanding and violation of Forest regulations by timely and tactful advice rather than to follow up violations by the exercise of their authority." [70] To help win popular respect, the Forest Service generally placed officers in districts close to their homes. This practice, followed even in recent years when possible, became especially important in eastern forests where the intermingling of Federal and private lands brought the Forest Service and the local population into greater contact than generally occurred in the West.

Reference Notes

1. Wilma Dykeman, The French Broad (New York: Rinehart and Company, 1955), pp. 166-177. See also F. D. Eubank, "Early Lumbering in East Tennessee," Southern Lumberman (December 15, 1935): 100. A good general source on the logging boom in the Southern Appalachians is Ronald D. Eller, Chapter III, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers: The Modernization of the Appalachian South, 1880-1930," Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina, 1979.

3. Ronald D. Eller, "Western North Carolina, 1880-1940: The Early Industrial Period," Chapter II of Draft Version, Socio-Economic Overview in Relation to Pisgah-Nantahala National Forest. (Prepared for National Forests of North Carolina by the Appalachian Center at Mars Hill College, N.C., 1979), p. 14. See also Eller's "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," Chapters II and III.

4. W. B, Webb, "Retrospect of the Lumber Industry in Eastern Kentucky: Story of Fifty Years of Progress," Southern Lumberman 113 (December 22, 1923): pp. 175, 176; Burdine Webb, "Old Times in Eastern Kentucky," Southern Lumberman 193 (December 15, 1956): 178G-178I; and the W. M. Ritter Lumber Co., The Romance of Appalachian Hardwood Lumber; Golden Anniversary, 1890-1940 (Richmond, Va.: Garrett and Massie, 1940), pp. 13, 14.

5. Michael Frame, Strangers in High Places: The Story of the Great Smoky Mountains (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., 1966), pp. 157, 166; Douglas Brookshire, "Carolina's Lumber Industry,"Southern Lumberman 193 (December 15, 1956): 162; Robert S. Lambert, "Logging the Great Smokies, 1880-1930," Tennessee Historical Quarterly 20 (December 1961): 350-363; Robert S. Lambert, "Logging on Little River, 1890-1940," The East Tennessee Historical Society, Publications Number 33 (1961): 32-43; "Knoxville," Hardwood Record (November 10, 1911): 293; Alberta Brewer and Carson Brewer, Valley So Wild: A Folk History (Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1975), p. 310; Ernest V. Brender and Elliott Merrick, "Early Settlement and Land Use in the Present Toccoa Experimental Forest," Scientific Monthly 71(1950): 323.

6. Harry Caudill, Night Comes to the Cumberlands, (Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1976), p. 64.

7. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," pp. 94, 95.

8. Marion Pearsall, Little Smoky Ridge, The Natural History of a Southern Appalachian Neighborhood (University, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1959), p. 70.

9. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," p. 96. Similarly, Forest Service surveyors and purchasing agents often found titles, claims, and surveys to be haphazard when they entered the mountains in 1911 and 1912. Examinations.

10. Judge Watson, "The Economic and Cultural Development of Eastern Kentucky from 1900 to the Present," Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, 1963, p. 45; Caudill, Night Comes to the Cumberlands, pp. 62-71.

11. Lambert, "Logging the Great Smokies," 361; Brookshire, "Carolina's Lumber Industry," 162; Ruth Webb O'Dell, Over the Misty Blue Hills: The Story of Cocke County, Tennessee (n.p., 1950), p. 195.

12. Brookshire, "Carolina's Lumber Industry," 162; Webb, "Retrospect of the Lumber Industry": 175.

13. O. D. Ingall to The Forester, May 10, 1912. National Archives, Record Group 95, Records of the Forest Service, Region 8, Nantahala.

14. Watson, "The Economic and Cultural Development of Eastern Kentucky," p. 131.

15. Ignatz James Pikl, Jr., A History of Georgia Forestry, (Athens: University of Georgia, Bureau of Business and Economic Research, Monograph #2, 1966), p. 17; Roderick Peattie, ed., The Great Smokies and the Blue Ridge: The Story of the Southern Appalachians (New York: The Vanguard Press, 1943), p. 155; Shackelford and Weinberg, Our Appalachia (New York: Hell and Wang, 1977), p. 113.

16. Ronald Eller, "Industrialization and Social Change in Appalachia, 1880-1930," in Helen Mathews Lewis, Linda Johnson and Don Askins, eds., Colonialism in Modern America: The Appalachian Case, (Boone, N.C.: The Appalachian Consortium Press, 1978), p. 39.

17. Bureau of the Census, Thirteenth Census of the U.S. Taken in the Year 1910, Volume I, Population (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1913). Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the U.S. Taken in the Year 1920, Volume VI, Agriculture (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922).

18. Eller, "Industrialization and Social Change," p. 39.

19. Lambert, "Logging the Great Smokies, p. 168. Brewer and Brewer, Valley So Wild, p. 311.

20. Carl Alwin Schenck, Birth of Forestry in America, Biltmore Forest School, 1898-1913 (Santa Cruz, Calif.: Forest History Society and the Appalachian Consortium, 1974), p. 148.

21. Marion Pearsall, Little Smoky Ridge, The Natural History of a Southern Appalachian Neighborhood (University, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1959), p. 67.

22. Horton Cooper, History of Avery County, North Carolina (Asheville: Biltmore Press, 1964).

23. Alan Hersh, "The Development of the Iron Industry in East Tennessee," Master's thesis, University of Tennessee, 1958.

24. Perry, McCreary Conquest, pp. 7, 13.

25. There are no comprehensive histories of the coal industry or mining in general in the Southern Appalachians. Caudill's Night Comes to the Cumberlands presents an undocumented analysis of the impact of coal on eastern Kentucky. Another coal classic is Theodore Dreiser, Harlan Miners Speak (New York: Da Copo Press, 1970). Other selected works on the development of the coal industry in the region include Charles E. Beachley, The History of the Consolidation Coal Company 1864-1934 (New York: Consolidation Coal Company, 1934); Edward Eyre Hunt, Frederick G. Tryon, and Joseph H. Willilts, What the Coal Commission Found (Baltimore: Williams and Wilkens, 1925); Winthrop D. Land, Civil War in West Virginia: A Story of the Industrial Conflict In The Coal Mines (New York: B. W. Huebsch, Inc., 1921); Howard B. Lee, Bloodletting in Appalachia (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 1969); Malcolm Ross, Machine Age in the Hills (New York: The McMillan Company, 1933); and William Purviance Tams, Jr., The Smokeless Coal Fields of West Virginia: A Brief History (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 1963). Eller, "Miners, Millhands and Mountaineers," Chapters IV and V, is the source of this account of the coal regions of the Southern Appalachians.

26. W. W. Ashe, "The Place of the Eastern National Forests in the National Economy," Geographical Review 13 (October, 1923), p. 535.

27. John F. Day, Bloody Ground (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Co., Inc., 1941), p. 190.

28. Shackelford and Weinberg, Our Appalachia, pp. 116-118, 121, 122.

29. Eller, "Western North Carolina, 1880-1940," p. 8.

30. Lambert, "Logging the Great Smokies," pp. 39, 359.

31. Henry P. Scalf, Kentucky's Last Frontier (Prestonburg, Ky.: Henry P. Scalf, 1966), p. 217.

32. Pearsall, Little Smoky Ridge, p. 69.

33. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," p. 163.

34. Message From the President of the United States Transmitting a Report of the Secretary of Agriculture in Relation to the Forests, Rivers, and Mountains of the Southern Appalachian Region (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902), p. 24.

35. General sources for the conservationist movement in the United Slates include Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement. 1880-1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959); Roderick Nash, ed., The American Environment: Readings in the History of Conservation (Reading, Mass.: Addison Wesley Publishing Company, 1968); Elmo R. Richardson, The Politics of Conservation: Crusades and Controversies. 1897-1913 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962); and Grant McConnell, "The Conservation Movement—Past and Present," Western Political Quarterly VII (1954): 463-478.

36. Nash, The American Environment, p. 89.

37. 26 Stat. 1103, 16 U.S.C. 471. 30 Stat. 34, 16 U.S.C. 473-482, 551.

38. Earl H. Frothingham, "Biltmore—Fountainhead of Forestry in America," American Forests 47 (May, 1941): 215. See also John Ross, "'Pork Barrels' and the General Welfare: Problems in Conservation, 1900-1920" Ph.D. dissertation, Duke University, 1969, pp. 2-10.

39. Schenck, Birth of Forestry, p. 25. Other references to the conditions of the Biltmore lands before and after the Vanderbilt purchase are found in Dykeman, The French Broad; Josephine Laxton, "Pioneers in Forestry at Biltmore," American Forests 37 (May, 1931); and Overton W. Price, "George W. Vanderbilt, Pioneer in Forestry," American Forestry 20 (June, 1914).

40. Gifford Pinchot, Breaking New Ground (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1947), p. 66, 68. (Reprinted by University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1972.)

41. Harold T. Pinkett, "Gifford Pinchot at Biltmore," The North Carolina Historical Review 34 (July, 1957): 351.

43. Harley E. Jolley, "The Cradle of Forestry in America," American Forests 76 (December, 1970).

44. John B. Woods, "Biltmore Days," American Forests 54 (October, 1948): 452.

45. Schenck, Birth of Forestry, p. 52.

46. Schenck, Birth of Forestry, p. 118.

47. Harley E. Jolley, "Biltmore Forest Fair, 1908," Forest History 14 (April, 1970): 10, 11.

48. J. B. Atkinson, "Planting Forests in Kentucky," American Forestry 16 (August, 1910): 449-453.

49. Elwood R. Maunder and Elwood L. Demmon, "Trailblazing in the Southern Paper Industry," Forest History 5 (Spring, 1961): 7.

50. Josephine Laxton, "Pisgah—A Forest Treasure Land," American Forests 37 (June, 1931): 340.

51. C. P. Ambler, The Activities of the Appalachian National Park Association and the Appalachian National Forest Reserve Association (Asheville, N.C., August, 1929), p. 6.

52. George Perkins Marsh, Man and Nature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, reprinted 1967).

53. Message From the President of the United States, p. 34.

54. Eller, "Western North Carolina, 1880-1940," p. 26.

55. Ashley L. Schiff, Fire and Water, Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962), pp. 116-122. Harold K. Steen, The U.S. Forest Service, A History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976), p. 126.

56. Ambler, Activities of the Appalachian National Park Association, pp. 28, 29. This group changed its name to the Appalachian National Forest Reserve Association in 1903.

57. Bernard Frank, Our National Forests (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1955), p. 12. See also Michael Frome, The Forest Service (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1971), p. 17.

58. For more detailed information on the background to passage of the Weeks Act, see Ross, "'Pork Barrels' and the General Welfare: Problems in Conservation, 1900-1920"; for a briefer account, John Ise, The United States Forest Policy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1920), pp. 212-223.

59. 36 Stat. 962; 16 U.S.C. 515, 521.

60. Charles Smith, "The Appalachian National Park Movement, 1885-1901," North Carolina Historical Review 37 (January, 1960): 44-47.