|

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81 |

|

Chapter II

National Forests Organized in Southern Appalachians

The Weeks Act, establishing Federal authority to purchase lands for National Forests, was signed by President William Howard Taft on March 1, 1911. Almost immediately, the Forest Service examined, and optioned for purchase, lands in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. The first National Forest there was proclaimed by President Woodrow Wilson on October 17, 1916; more followed in 1920. By 1930 thousands of acres of culled or cutover mountain lands had been acquired and the Forest Service had begun its ambitious, long-term effort for environmental and economic stabilization of the region.

Within a week, the Act became law and the National Forest Reservation Commission had been appointed and had met for the first time. [1] In anticipation of the new law, the Forest Service had been working for many months to select a large number of precisely defined, very large tracts suitable for purchase, in the most promising areas, for Commission approval. These tracts, designated "purchase units," roughly bounded the mountain headwaters of navigable streams. Each unit was at least 100,000 acres (156.25 square miles, or 40,469 hectares) in size, and most were much larger. Final surveying and mapping was done early in March, and on March 27 the Commission announced the establishment of 13 purchase units, 7 of which were in the Southern Appalachians. By the end of fiscal year 1912, four more units in the region were announced. All 11 are listed in table 2.

Table 2.—The 11 Original National Forest Purchase Units in the Southern Appalachians

| Name | Location | Initial Gross Acreage |

| 1911 | ||

| Mt. Mitchell | North Carolina | 214,992 |

| Nantahala | North Carolina and Tennessee | 595,419 |

| Pisgah | North Carolina | 358,577 |

| Savannah | Georgia and South Carolina | 367,760 |

| Smoky Mountains | North Carolina and Tennessee | 604,934 |

| White Top | Tennessee and Virginia | 255,027 |

| Yadkin | North Carolina | 194,496 |

1912 | ||

| Boone | North Carolina | 241,462 |

| Cherokee | Tennessee | 222,058 |

| Georgia | Georgia and North Carolina | 475,899 |

| Unaka | North Carolina and Tennessee | 473,533 |

| Total | 1,412,952 | |

Source: The National Forests and Purchase Units of Region Eight, Forest service unpublished report, Region 8 (Atlanta, Ga., January 1, 1965), p. 5.

The boundaries of these units were altered several times in later years, as lands were reevaluated and new lands became available for purchase. When the units were incorporated into National Forests, after sufficient lands had been acquired, some of the names were retained as the names of the new forests. Four Southern Appalachian purchase units were added considerably later: the French Broad in North Carolina and Tennessee (1927), the Cumberland in Kentucky (1930), the Chattahoochee in Georgia (1936), and the Redbird in Kentucky (1965). Of the original purchase units, no land was ever purchased in the Great Smoky Mountains area, and the Yadkin Unit was still inactive in 1982 and likely to remain so.

With the establishment of official purchase units, the actual acquisition process began, on something of an ad hoc basis. Although modified over the years, the procedure remained essentially the same in 1982. First, advertisements requesting offers to sell land within the purchase unit boundaries were published in newspapers throughout the area. Upon reasonable offers of sale, the lands in question were examined and surveyed and, if deemed suitable, were recommended for purchase to the National Forest Reservation Commission. The Commission, usually meeting twice each year, considered each tract separately. Depending upon the availability of funds, purchases were consummated within several months to a year of approval.

By June 30, 1911, 1,264,022 acres of land had already been offered for sale by owners; of those, about 150,000 had been examined. Reputedly, the first land to receive preliminary Commission approval was a tract of over 31,000 acres offered on April 14, 1911, by Andrew and N.W. Gennett of the Gennett Land and Lumber Co. of Atlanta. [2] The tract, located in Fannin, Union, Lumpkin, and Gilmer Counties, Ga., was in an area which had formerly been "rather thickly settled" with small farms but was now almost abandoned. Although some of the tract had deteriorated with misuse, enough marketable timber remained to command a price of $7.00 per acre.

The Gennetts were probably eager to sell the tract because it was not immediately accessible. The nearest rail point was located from 16 to 25 miles away. [3] Indeed, after Commission approval of their first tract, the Gennetts offered 13,000 acres of land belonging to the Oaky Mountain Lumber Co., of which Andrew Gennett was President, in Rabun County, Ga. Gennett proclaimed his Oaky Mountain lands to be "solid and compact . . . as well timbered as any portion of that section . . . [and] not over 300 or 400 acres has ever been cleared." [4] In January 1913, the National Forest Reservation Commission approved the purchase of 7,335 Oaky Mountain acres at $8.00 per acre; additional Gennett tracts of 10,170 and 2,200 acres were approved in 1917 and 1919. [5]

The first tract actually purchased was an 8,100-acre tract of the Burke McDowell Lumber Co. in McDowell County, near Marion, N.C. This tract was officially approved at the same meeting the first Gennett tract was—on December 9, 1911; however, payment for it was made on August 29, 1912, almost 4 months before the Gennett tract was paid for. The Burke McDowell tract sold for just over $7.00 per acre. [6]

|

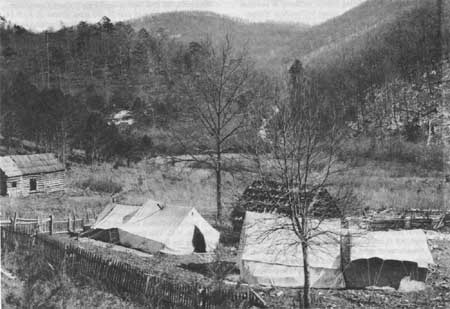

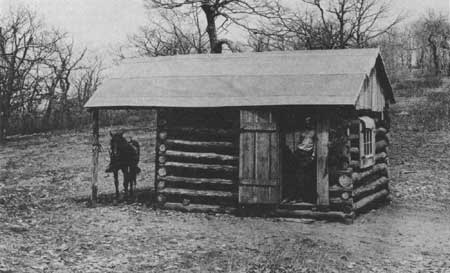

| Figure 24—Forest boundary survey crew camp No. 1 on Pfister & Vogel timber lands, Union-Fannin counties, North Georgia, in December 1911, preparatory to Federal purchase under the Weeks Act of March 1, 1911. This area became part of the Savannah Purchase Unit, which later became a portion of the Chattahoochee National Forest. (National Archives: Record Group 95G-10411A) |

Best, Largest Tracts Acquired First

The size and quality of the Gennett and McDowell tracts are representative of many of the earliest lands purchased in the Southern Appalachians. Generally, although many small owners sold tracts in the 100- to 300-acre category, some of the best and largest tracts were acquired first. Purchasing a few large tracts was an easier way to establish national forest acreage than purchasing many smaller tracts, and lumber companies were often willing to sell large tracts. The Forest Service maintained, however, that the boundaries of the purchase units were not necessarily drawn to include large tracts. In 1912, William Hall, Assistant Forester in charge of acquisition, advised his forest examiners near Brevard, N.C., "the question of whether a locality is to be put in a purchase area should be determined entirely irrespective of whether the lands are held in small or large holdings." [7]

Nearly 30 percent of the lands bought in the first 5 years in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia were virgin timber. [8] Most of the remaining land had been partially cleared or culled for specific types of timber, especially yellow- (tulip) poplar and chestnut. Few of the first tracts purchased were totally cutover, although the proportion of cutover lands acquired increased over the years. The largest tracts were purchased almost without exception from lumber companies or land investment concerns. Most such land was either sparsely populated or uninhabited, the residents having left as the land was depleted and acquired by investors for its remaining timber. In the case of the Gennett tract:

the emigration tendency in the vicinity of this tract was so strong that the remaining settlers have been unable to maintain schools and churches or keep roads in good condition. This situation has made it easy for a body of land of the size of this tract to be assembled . . . [9]

The quality of lands purchased varied considerably over the Southern Appalachian region. The best lands were those where topography and remoteness had delayed road and rail access. For example, the Nantahala Purchase Unit of far southwestern North Carolina was thought to contain "some of the best and most extensive virgin forests of the hardwood belt." [10] Among the first lands purchased there were about 21,000 acres of the Macon Lumber Co., high in the mountains. Only 102 acres of the tract had been cleared, "and the only settler [in 1912] is the keeper employed by the Company." [11] The lands sold for $11 per acre. Another early Nantahala purchase was over 16,000 "well-timbered" acres of the Macon County Land Co., sold between 1914 and 1919 for between $8 and $9 per acre. [12]

On the other hand, lands offered in the Cherokee and Unaka purchase units appear to have been lower and less uniform in quality. Of over 275,000 acres not in farms in the Unaka area in 1912, 40 percent of the land was estimated to have been cutover or culled, and on another 40 percent of the land, timber operations were ongoing, with at least 15 large sawmills and more than 50 smaller ones. Moreover, of 24,050 acres of "virgin" timber being offered for sale in the Unaka area as of March 1912, 22,000 were subject to timber reservations on all trees above 10 inches in diameter. [13]

Similarly, in the Cherokee Purchase Unit, much of the timber on the offered lands was either cutover, being cut, or reserved. In 1913 the Alaculsy Lumber Co. of Conasauga, Tenn., offered 32,000 acres, all of which were cutover or subject to a timber reservation. [14] Of the over 53,000 acres of the Tennessee Timber Co. surveyed between 1913 and 1915, sections had been extensively damaged by smoke and sulfur fumes from the smelting operations of the Tennessee Copper Co. and the Ducktown Sulfur, Copper, and Iron Co. near Ducktown, Tenn. [15] In certain areas, particularly northern Georgia and southwestern North Carolina, the Forest Service gained possession of finely timbered "virgin" forests. However, more often than not, the lands acquired, especially in later years, had been cleared, misused, or at least selectively culled.

|

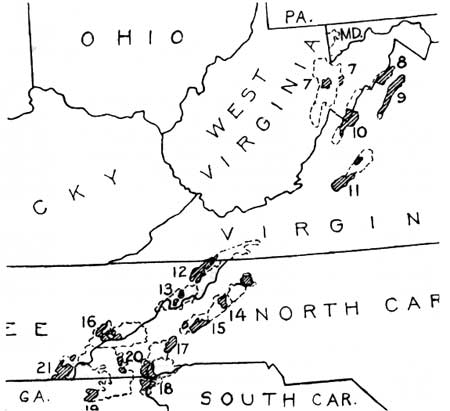

| Figure 25—Forested areas of the Southern Appalachian Mountains that were selected for purchase as National Forests under the Weeks Act of March 1, 1911, as of the summer of 1915. Dotted lines enclose proposed Forest boundaries; shaded portions show where lands had been acquired or were in process of acquisition. These various "purchase areas" or "purchase units" shown here, together with newer ones, were later consolidated and incorporated into nine National Forests. The numbered Purchase Units and the Forests that evolved are: 7, Monongahela; 8, Potomac; 9, Massanutten, and 10, Shenandoah, all three of which became the Shenandoah National Forest on May 16, 1918, and then the George Washington National Forest on June 28, 1932; 11, Natural Bridge, which became a Forest of that name in 1918 and then part of the George Washington in 1933; 12, White Top, and 13, Unaka, which together became the Unaka National Forest on July 24, 1920, and then part of the Cherokee on April 21, 1936 (except for the Virginia portions which became part of the new Jefferson National Forest); 14, Boone, 15, Mt. Mitchell, and 17, Pisgah, which all became part of the enlarged Pisgah National Forest by 1921; 18, Savannah, and 20, Nantahala, which together became the Nantahala National Forest on January 29, 1920; 19, Georgia, and 21, Cherokee, which together became the early Cherokee National Forest on June 14, 1920; and 16, Smoky Mountains Purchase Area, which finally became the southern half of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Georgia portion of Nos. 18 and 19 later became the nucleus of Chattahoochee National Forest. The South Carolina portion of No. 18 later became part of Sumter National Forest. (Forest Service map and photo) |

Formal Field Surveys Required

Because all lands obtained under Weeks Act authority had to be acquired and paid for on a per-acre basis, a formal survey of each tract was necessary before it could be recommended for purchase. Survey work on the tracts offered during the early years was difficult, time-consuming, and costly. Many were remote and inaccessible, steep, and covered with dense undergrowth. Before the land examiners came to cruise the Gennett tract in northern Georgia, for example, Gennett warned them that it would take at least 10 days to go over the tract and that it would be very difficult to get accommodations, "and in some portions of the tract, it will be absolutely impossible." [16]

Most of the offered tracts had never been surveyed before, and often the owners had only a general awareness of their boundaries, as the letters and reports of the first survey teams recurringly attest. Thomas Cox, Survey Examiner in Georgia, wrote in his January 1914 report, "Tracts difficult to locate as owners do not know anything definate [sic] of corners." In surveying the Vanderbilt lands of the Pisgah Unit in 1914, James Denman wrote, "no one either in Vanderbilt employ or otherwise seems to know much about the location of their lands on the ground." [17] Indeed, sometimes lot descriptions were based on tree lines that no longer existed; in these cases, surveyors persuaded adjacent landowners to establish ad hoc corners and sign an agreement accordingly. [18]

Surveying for early Forest Service acquisitions in the Southern Appalachians even required surveying a county line for the first time. The boundary between Swain and Macon Counties, N.C., established in 1871, had never actually been surveyed; essentially it followed clear natural or man-made boundaries, except for an arbitrary line between the Nantahala and Little Tennessee Rivers. In June 1914 the Forest Service surveying party established the boundary on the ground. [19]

Much of the surveyor's work involved resolving tract overlappings where lands were claimed by more than one owner. In parts of the southern mountains, early grants had been made and titles transferred—to the apparent ignorance or indifference of the current occupant. Many of the old grants in the Mt. Mitchell area were found so vague in description that they were almost impossible to locate. [20] Throughout the area lands had been claimed and counterclaimed with both parties often sharing the property in ambiguous peace until the Forest Service surveyors arrived. Upon initial survey of the Vanderbilt tract, at least seven claimants refused to acknowledge Vanderbilt title. An extreme example of the earnestness of such claimants is the Dillingham family, who claimed several sections of the Big Ivy Timber Co. lands near Mt. Mitchell. According to a 1914 letter from Thomas Cox, examiner of surveys, Ed Dillingham went so far as to build a fence around one of his Big Ivy claims, and "has gone to every length to forceably stop the survey and have me arrested." [21]

An unusual example of overlapping claims to ownership involved the Olmstead lands in the Nantahala Purchase Unit. In 1868, the Treasury Department had taken possession of the lands of E.B. Olmstead (not to be confused with Frederick Law Olmstead) who was convicted of embezzling funds from the U.S. Post Office Department. In 1912 these lands were transferred from Treasury to the Secretary of Agriculture. No Federal survey of the lands had occurred until the Forest Service came in 1913; before then, the "local populace were not generally aware of the Government's claim to ownership." [22] Consequently, there were scores of claims against portions of the land, 22 of which were not resolved until passage of the Weaver Act in 1934 which granted possession to all claimants and thus assured them of payment, and the U.S. Government of bona fide deeds. [23]

Perhaps the most serious example of overlapping claims involved the Little River Lumber Co. lands in Tennessee. Failure to establish clear title eventually led to the abolishment of the Smoky Mountains Purchase Unit, and thus influenced dramatically the course of history in the area.

As early as 1912, surveyors and examiners were cruising the large acreage of the Little River Lumber Co. and nearby smaller tracts of the Smoky Mountains unit. Several small landowners offered to sell right away, and by 1913 their proposals had been accepted by the National Forest Reservation Commission. By 1915 at least 8,050 acres in five separate units of the Little River Lumber Co. had also been approved for purchase. [24] However, no land in the Smokies was ever actually purchased. Titles predating occupancy by the Little River Lumber Co. were simply difficult, if not impossible, to clear to the Government's satisfaction. With the onset of World War I, the company, unable to wait for Federal title searches any longer, cancelled its offers of sale, and the purchase unit was subsequently rescinded. [25] With Forest Service interest in the area abandoned, in 1923 a movement began to promote the idea of a National Park in the Great Smoky Mountains.

|

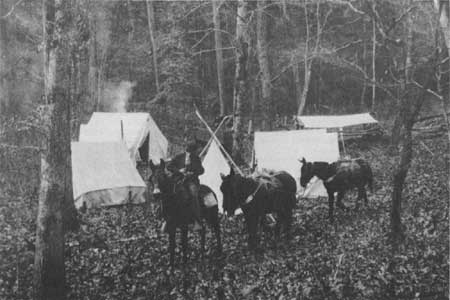

| Figure 26—Camp of forest boundary survey crew on lands of Little River Lumber Company, Great Smoky Mountains, Blount County, Tenn., in December 1911, just 9 months after passage of the Weeks Act. This area is now in the National Park, but then was scheduled to be in a new National Forest. (NA:95G-10071A) |

Reactions to Federal Purchase

From the evidence available, it appears that the initial reaction of the people in the Southern Appalachians to the coming of the Forest Service was generally favorable in spite of some skepticism and distrust. Two written comments on early popular reaction to Weeks Act purchases came from Forest Service personnel. D.W. Adams, timber cruiser, wrote to Forester William Hall in September 1911, from Aquone, N.C., "The people generally, particularly on the Mt. Mitchell Unit, have been decidedly skeptical as to the purchase of lands by the government . . ." Verne Rhoades, forest examiner, a graduate of the Biltmore School of Forestry, and later the first supervisor of the Pisgah National Forest, writing of the Unaka area in February 1912, reported that "The people in general regard most favorably the movement on the part of the government to purchase these mountain lands." [26]

The large number of tracts quickly offered for sale testifies to a generally favorable reaction. For timber companies, sale to the Government offered an opportunity to rid themselves of cutover, useless land, or lands which, even though finely timbered, were inaccessible or steep. Sale to the Government thus offered payoffs for their speculation and risk and a lightening of their tax burdens. For small landholders, Forest Service acquisitions offered an undreamed-of profit on lands that no one else would pay for. The "lands nobody wanted"—if they were in the right place—were wanted by the Forest Service. [27]

The prices paid by the Forest Service were respectably high, especially in the early years. The Federal purchase process itself contributed to high land values. As O.D. Ingall, Forest Service agent, wrote from Andrews, N.C., in May 1912, "the government ties up the land for months and puts the owner to a great deal of trouble and expense." Besides delay, the owner might lose acreage through the careful surveys required and be put to considerable expense to prove title to the government's satisfaction. [28]

In addition, in the early years of acquisition, Forest Service survey teams and timber cruisers sometimes assessed tracts which had not yet been formally offered for sale. In such a case, a wily owner, whose corners had been set and boundaries located at no personal expense, would hold out for a higher price—figuring that the Government would not want to lose the cost of survey. [29] Initially, too, a number of land agents operated throughout the area to obtain a fee for boosting a seller's price. William Hall, Assistant Forester, wrote in September 1911:

The effect of the work of agents in offering lands under the Weeks Act is in most cases bad. They tend to increase the price of land above what it ought to be and will make it difficult for the government to buy at a reasonable price. [30]

As early as April 1911, the National Forest Reservation Commission discussed the role of agents and determined to deal only with owners themselves. Hall warned his land acquisition teams to "be on . . . guard at all times" against such unscrupulous agents. [31]

Although there were some landowners who, in ignorance, asked too low a price and others who sacrificed land for sure money, on the whole, the southern mountaineers had become sophisticated negotiators and traders. The willingness of small landowners to sell their land depended in part on whether other owners in the area had already sold. R. Clifford Hall, forest assistant, noted in 1913 that it required "much time and patience" to deal with the "wavering" small landowners of the Hiwassee area of extreme northern Georgia. [32] A year later he found negotiation even more difficult:

The small owners of this section are very hard to deal with, as all the 'traders' have sold out to the various buyers that have scoured the country. Where the land is so located adjacent to what we are getting as to be especially desirable, and the owner talks as if he might sell but will not sign a proposal, we should make the valuation now in order to be able to name a price and get a legal option without delay when he happens to be in a 'trading humour'. [33]

It was in considering such problems of price negotiation that the National Forest Reservation Commission discussed the use of condemnation. Although the Weeks Act did not make a specific provision for condemnation, the Commission assumed it had such authority. [34] William Hall, for one, felt that if the people know condemnation was a possibility, they would be more willing to sell at reasonable prices. [35] Nevertheless, the Commission determined it was "inexpedient" to condemn—except to clear title—and best to proceed with purchase as far as possible. This early decision by the Commission is a policy still followed by the Forest Service.

In spite of the generally high prices offered for the earliest purchases, as time went on and the delays between offer and survey, or between recommendations for purchase and payment, lengthened, the acquisition process could bring frustration, disillusionment, and anger. In the Smoky Mountains Unit, for example, Forest Examiner Rhoades noted in 1913 that several small landowners, who had been asked to discontinue milling operations while their tracts were being considered by the Commission, were becoming "restless and dissatisfied." [36] Similarly, a mill operator on the Burke McDowell tract near Mt. Mitchell, who had suspended operations during examination and survey, was reported to be "exceedingly reluctant to quit manufacturing timber and . . . very impatient with McDowell . . ." [37] In 1915, in the Mt. Mitchell area, the elderly J.M. Bradley had been waiting for his money for so long that his relatives "were afraid that he would lose his mind over it. . ." [38] J.W. Hendrix of Pilot, Ga., threatened in 1914 to stop the sale of his over-350 acres if the Forest Service did not proceed more rapidly:

I am in neede of money and I am ready to close the deal. I am going to give you a little time to cary out this contract, and if you do not take the matter up in a reasonable length of time, I will cansel the sale of this property. [sic.] [39]

And Miss Lennie Greenlee of Old Fort, N.C., wrote to Ashe that:

the time-killing propensities of this band of surveyors is notorious, although were the saying reported to them they would revenge themselves by doubling the gap of time between them and my survey. [40]

The First National Forests

As stated in the Secretary of Agriculture's Report to Congress in December 1907, the original thought behind the establishment of the eastern National Forests was that 5 million acres in the Southern Appalachians and 600,000 acres in the White Mountains should be acquired. By 1912, these numbers still appeared appropriate, but it was determined unnecessary to purchase all the land within any given purchase unit; between 50 and 75 percent was considered enough. [41] According to Henry Graves' Report of the Forester for 1912:

There is every reason to believe that the purpose of the government may be fully subserved by the acquisition of compact bodies each containing from 25,000 to 100,000 acres well suited for protection, administration and use. [42]

|

| Figure 27—The National Forests of the Southern Appalachians in 1921. The Pisgah was established in 1916, the Shenandoah, Natural Bridge, and Alabama in 1918, and the Nantahala, Monongahela, Cherokee, and Unaka all in 1920. (Forest Service map and photo) |

Four Million Acres Acquired by 1930

Purchase of land for National Forests in the East continued fairly steadily throughout the two decades of 1911-31. By the end of fiscal year 1930, 4,133,483 acres had been acquired under the Weeks Act. The first Weeks Act appropriation of $11 million lasted for 8 years, through fiscal year 1919; only $600,000 was appropriated in 1920, and $1 million in 1921. Throughout the 1920's, typically about one-half of what the Forest Service requested was appropriated. [43] The number of acres purchased in any given year was primarily dependent upon funds available; there always were, and still are (1982), more tracts offered for sale than appropriated money could purchase.

In the Southern Appalachians, Weeks Act acquisitions were heaviest between 1911 and 1916, when some of the largest tracts of today's Pisgah, Nantahala, Chattahoochee, Cherokee, and Jefferson Forests were purchased. Most land was purchased in large tracts of more than 2,000 acres. Indeed, some 60 percent of the Nantahala National Forest was acquired from only 22 sellers, mostly lumber companies or land investment concerns. About 80 percent of the Pisgah National Forest was purchased from 29 sellers. The largest tract from a single owner was its nucleus of 86,700 acres from the Biltmore Estate.

Vanderbilt had had his lands preliminarily surveyed shortly after the Weeks Act passed. Purchase negotiations began in 1913, when members of the National Forest Reservation Commission, Chief Forester Graves, and other Forest Service personnel visited the Biltmore estate and Vanderbilt's hunting lodge on Mt. Pisgah. Vanderbilt died before a purchase agreement was reached, but after his death, his widow, Edith Vanderbilt, consummated the sale on May 21, 1914, for $433,500. This vast, cohesive tract became the core of the first National Forest in the Appalachians, the Pisgah, on October 17, 1916. With a gross acreage of over 355,000, only 53,810 acres had actually been purchased in 1916, but an additional 34,384 acres had been approved. On November 7, 1916, President Wilson proclaimed Pisgah a National Game Preserve as well.

In 1918, the Natural Bridge National Forest was created in western Virginia. Then, in 1920, four more National Forests were proclaimed in the Southern Appalachians: the Boone in North Carolina (January 16, 1920); the Nantahala in North Carolina, Georgia, and South Carolina (January 29, 1920); the Cherokee in Tennessee (June 14, 1920); and the Unaka in Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia (July 24, 1920). Of these, only the Nantahala and Cherokee names remain: the Boone was joined to the Pisgah in March 1921; the Unaka was partitioned among the Pisgah, Jefferson, and Cherokee in 1923 and 1936. Until 1936 when the Chattahoochee and Sumter National Forests were proclaimed, the boundaries of the forests and purchase units in the area were somewhat fluid.

After the establishment of the first five National Forests in the southern mountains, the National Forest Reservation Commission turned its attention over the next decade to other eastern areas. Noticeable progress having been made toward protection of the headwaters of navigable waterways, the Commission broadened its perspective; by 1923 the members felt the National Forest system should be extended to all Eastern States, "to arouse the interest of landowners in these states in managing their properties for permanent timber production." [45] After a select Congressional Committee headed by Senator Charles McNary and Representative John Clarke met in 1923, this idea became embodied in the Clarke-McNary Act of 1924, which expanded the Weeks Act. [46] This act allowed purchases outside of navigable river headwaters. It also expanded Federal-State cooperation in fire protection and in production and distribution of seeds and seedlings for forest planting. Under Clarke-McNary, new purchase units were established in the southern coastal plains and Great Lakes States.

On March 3, 1925, the Weeks Law Exchange Act was passed, making consolidation of existing Forests easier in times of limited funding. [47] Under the Act, the Secretary of Agriculture can accept title to lands within the boundaries of National Forests in exchange for National Forest land or timber that does not exceed the offered land in value. This authority was used increasingly throughout the 1920's and after World War II, when Reservation Commission goals vastly exceeded the funds available. Thus, lands in the Southern Appalachian mountains continued to be acquired, although after 1920 the average size of the tracts and their quality decreased.

|

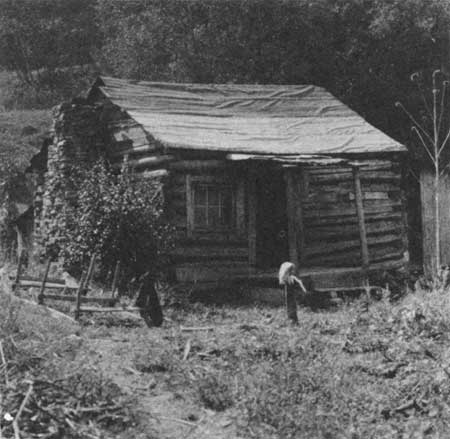

| Figure 28—Mountain farm with expanded log house surrounded by forest, Carter County, Tenn., on Unaka National Forest, September 1926. This area became part of the Cherokee National Forest in 1936. The old Unaka Forest was established in July 1920 after several years as a Purchase Unit. (NA:95G-212633) |

Forest Purchases Reduce Population, Farms

By 1930 the Forest Service had been a presence in the southern mountains for almost two decades. Within the purchase units and National Forests themselves, Federal lands were interspersed with those still held in private hands in an almost patchwork pattern of landownership. Inhabitants within and adjacent to National Forest boundaries were affected not only by the land acquisition program but by the ways in which the Forest Service managed its lands.

One of the most obvious effects of the first National Forest purchases in the Southern Appalachians was a decline in population growth and a decline in both farm acreage and number of farms. Although most of the first acreage purchased was timber company-owned, hundreds of small farms were acquired as well. In areas where many small landowners sold, the decline in population growth and in number of farms was marked.

This trend was especially evident in selected counties of northern Georgia where outmigration had been occurring before 1912. Union County, for example, whose population had declined by over 18 percent between 1900 and 1910, experienced another 7 percent decline between 1910 and 1920. Rabun County, where population had declined over 11 percent in the previous decade, experienced a population growth well below the State average between 1910 and 1920. Fannin and Towns Counties likewise experienced either no growth or an absolute population loss. This trend of population decline or slowing of growth, however, was not nearly so pronounced between 1920 and 1930.

A similar slowing of population growth took place in counties of North Carolina and Tennessee where large numbers of tracts were purchased early. For example, in Polk County, Tenn., population grew by only 0.9 percent between 1910 and 1920 (the State as a whole grew by 14 percent). In Macon and Graham Counties, North Carolina, population growth was only 6 and 3 percent respectively over the same decade. Yet, in adjacent Swain County—part of the Smoky Mountains Purchase Unit where no Forest Service acquisition occurred—population grew by 27 percent. [48]

Early acquisitions for National Forests are also reflected in agricultural statistics. In Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, the number of farms increased between 1910 and 1920, but, in counties experiencing heavy National Forest purchases, the number of farms declined. In Fannin and Rabun Counties, Ga., and in Buncombe and McDowell Counties, N.C., this decline was between 11 and 13 percent. The decline in farm acreage was more dramatic. The number of acres in farms dropped 39 percent in Rabun County, Ga., 37 percent in Buncombe County, N.C., 22 percent in Fannin County, Ga., and 21 percent in North Carolina's Macon County. [49] (This trend continued between 1920 and 1930, although the percentage decline in acreage was slightly less.) Thus, at least for selected counties, in areas where Federal land acquisition was initially extensive, there was a decided change both in demographics and in the pattern of landownership and land use.

Evidence of the mountaineers' first reaction to the coming of the Forest Service, beyond the letters already cited, is almost nonexistent. For example, a search through the Asheville Citizen from 1910 to 1920, reveals "little local reaction to the creation of the National Forest Reserves." Indeed, Eller has concluded that "most local residents reacted indifferently to the legislation." [50] It was not until Forest Service personnel arrived in the mountains that the consequences of the Weeks Act could be understood, and even then it does not appear that the people's reactions were reflected in the local newspapers.

When Forest Service staff first appeared in the purchase units and early ranger districts, they were the object of some suspicion and distrust. Ranger Roscoc C. Nicholson, the first, and for many years, district ranger in Clayton, Rabun County, Ga., wrote about this early reaction:

For several years the people . . . did not seem to know what to think of the government owning this land. Some of them did not like the idea of taking the land out from under taxation. Some thought they would be forced to sell their land and have to move out. . . Perhaps most of them thought at first that if they were stopped from burning out the woods they would never have any more free range and that the insects and other pests would destroy their crops. [51]

Many of the early rangers considered themselves highly dedicated considering the animosity they encountered. Former Forest Service supervisor Inman F. Eldredge, a graduate of the Biltmore School of Forestry, remembers that early foresters worked

. . . in a hostile atmosphere where the settlers in the national forests . . . were against you because the Forest Service hemmed them in. The stock men were against you because you were going to regulate them and make them pay for grazing, count their cattle and limit where they could go . . . The lumbermen were against you from the lumberjack up. They thought you were a silly ass . . . because you limited their action with the axe, and the people at the top thought you were a misguided zealot with crazy notions. People who work in that atmosphere have to have tough hides— dedication. [52]

|

| Figure 29.—The National Forests and proposed National Parks of the Southern Appalachian Mountains in 1930. Areas shaded with diagonal lines are the future Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina and Tennessee, and Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky. The small black dots and squares are State forests. The Qualla Indian Reservation in the Great Smokies was later renamed the Cherokee Indian Reservation. The National Forests are little changed from a decade earlier. (Forest Service map and photo) |

|

| Figure 30.—Subsistence mountain farm homes on wagon track, surrounded by forest, in Lee County, Ky., near Kentucky River about 45 miles southeast of Winchester, in summer 1926. Lee County, like adjacent Estill County, today has little National Forest land, although much is hilly and forested. (NA:95G-214116). |

|

| Figure 31.—Tiny crude inhabited log cabin with a small window and tarpaper roof in Lee County, Ky., summer 1926. Note stoneboat and sunflower stalk in front; also water pump and privy both very close to cabin and each other. Daniel Boone (then Cumberland) National Forest. (NA:95G-214118). |

|

| Figure 32—Log shack used as a temporary camp for Forest Service rangers and fire guards, near Silers Bald, Wayah Ranger District, Nantahala National Forest, west of Franklin, N.C., near present Nantahala Lake, in March 1916. Site was then a Purchase Unit. (NA:95G-27295A) |

Forest Fire Control Stressed

Such dedication, and a strong sense of mission, soon produced results. One of the earlier influences of the Forest Service in the Southern Appalachians was the control of fire. Deliberate burning was a traditional method of land management in the region. Such burning usually occurred in the late fall and early spring to clear the woods of snakes and insects, to increase pasturage, and to enrich the soil. Uncontrolled fires had been noted by the first survey and examination parties in 1911, since they delayed surveys and altered land valuations. For example, E.V. Clark, an examiner in Georgia, noted a fire set on private holdings in Lumpkin County which, before being checked burned almost 100 acres of the Gennett tract. Henry Johnson, examiner in the Cherokee area, noted in March 1914 that a week had been spent in firefighting and would continue for a month, "cattle-owners and others being determined to burn the range." [53]

In general, burning was practiced by various segments of the population—the lumbermen, farmers, hunters, railroad men, and mischief makers; violators were seldom convicted, and people seemed generally indifferent to stopping the practice. Yet, as more and more Federal land was acquired, deliberate burning on adjacent or proximate lands was a matter of increasing concern to the Forest Service. One of its early goals was to practice fire control and teach its neighbors to do likewise.

Indeed the Forest Service was extremely concerned about the evils of fire. Within the Forest Service, some dissension developed during the 1930's over the use of fire as a tool of forest management. It had been demonstrated that in the southern coastal pine forests, annual burning, by removing the thick ground cover of pine needles, grass and other vegetation, and disease spores, helped the forests to regenerate and flourish. This discovery, however, was suppressed as harmful to the overall fire control effort, and the dominant official view of fire as a universal enemy to the forest prevailed. [54] There is certainly no evidence that anyone in the Forest Service suggested that annual burning of the Southern Appalachian hardwood forests was a useful management technique. The Forest Service was completely unsympathetic with the local custom of burning the mountain woods.

Fire control on National Forest lands in the Southern Appalachians began almost immediately with their establishment. Ranger Nicholson described the early fire prevention work in Rabun County, Ga.:

Forest guards were appointed at a salary of $50 a month and went out on their tasks on horseback. There were then no towers or telephone lines. It was not until 1915 that the first telephone line was built from Clayton to Pine Mountain. [55]

The rangers generally enrolled several local men to serve as forest guards and firefighters. These men helped to spread the new idea of fire control throughout the community. The Forest Service spent nearly $100,000 for fire control in the Smoky Mountains Purchase Unit before it was rescinded. Local firefighters, construction crews, and trail builders were hired. A fire tower was built at Rich Mountain, near Hot Springs, now in the Pisgah National Forest, and a preliminary network of trails constructed. [56]

One of the main provisions of the Weeks Act was to establish a system of Federal-State cooperation to prevent and control forest fires. The South was the most deficient area of the United States in organized fire protection. When the Weeks Act was passed, no Southern Appalachian State had passed a fire protection law. The Weeks Act, by providing Federal funds (about $2,000 in the early years) to match State funds to support qualifying fire protection programs, thus encouraged legislatures to meet Federal standards.

Kentucky revamped its forest fire laws in 1912, appointed a State Forester, and began receiving Weeks Act fire protection funds; its first forest fire protection association was organized in Harlan County in 1914. Virginia appointed a State Forester in 1914; in 1915 fire patrols were started in several far western counties (on lands all of which later became part of the Jefferson National Forest), and the State began receiving Weeks Act fire funds. In 1915 North Carolina passed a new fire law, appointed a State Forester, formed its first fire protection association, and began receiving Weeks Act fire funds. Tennessee hired a forester in 1914, but did not begin receiving Weeks Act fire funds until after it organized a Bureau of Forestry in 1921. [57] After the Clarke-McNary Act provided expanded grants-in-aid for fire protection programs, Georgia in 1925 and South Carolina in 1928 developed State fire control systems. [58]

From available accounts of the period, Forest Service efforts to control and prevent fires in the southern mountains began to show results quite early. In 1920, the National Forest Reservation Commission minutes claimed a "tremendous improvement" in forest cover and regularity of stream flow. "After seven years the effects of the stoppage of fires were beginning to show on several Forests." [59] Nevertheless, throughout the next decade, firefighting continued to engage the activities and funds of most Southern Appalachian forest supervisors.

|

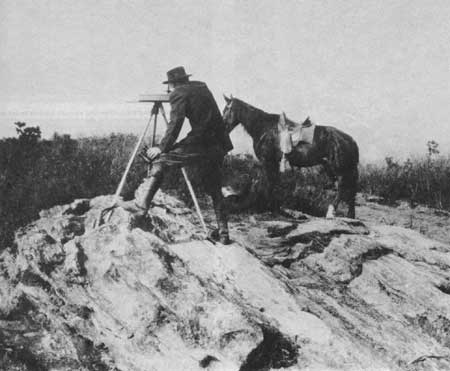

| Figure 33—Forest Service ranger on top of Satulah Mountain near Highlands, N.C., using an alidade to locate on his map a forest fire to the northeast in the direction of Chimney Top Mountain on the old Savannah Purchase Unit in April 1916. Note binoculars. This area near South Carolina and Georgia became part of the Nantahala National Forest in January 1920. (NA:95G-27296A) |

|

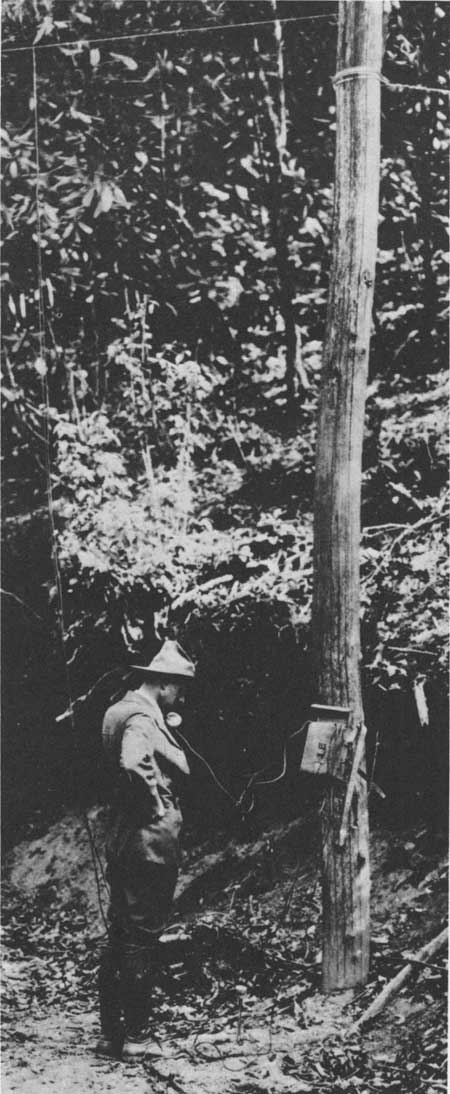

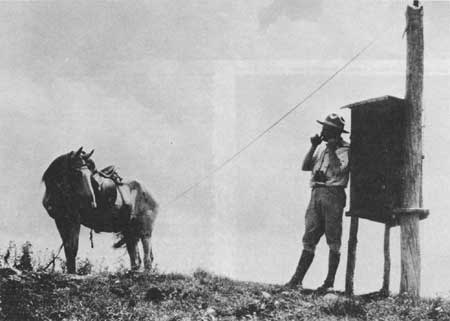

| Figure 34—Pisgah National Forest officer using a portable telephone hooked up to a newly installed Forest Service field line. Note wire hanging down from the overhead wire strung through the woods. The Pisgah was still a Purchase Unit when photo was taken in April 1916; it was officially established as the first purchased National Forest in the United States in October 1916. (NA:95G-27361A) |

|

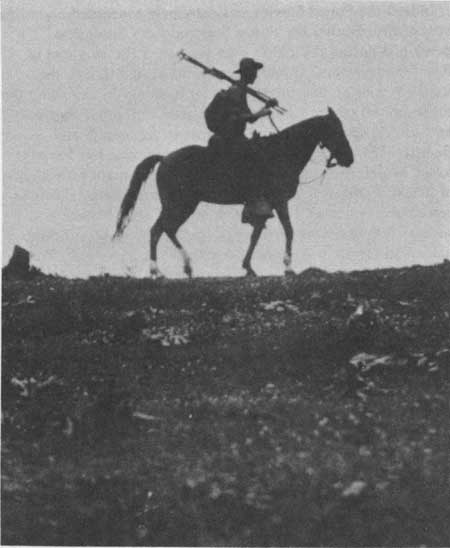

| Figure 35—A mounted Forest Service firefighter carrying hay rakes and a brushhook on his way to a forest fire on the Pisgah National Forest in 1923. (NA:95G-176511) |

|

| Figure 36—Four-man crew on way to forest fire on railroad handcar, with various hand tools including pulaski, axes, pitchforks, canvas bucket, and lantern. Pisgah National Forest, N.C., 1923. (NA:95G-176444) |

|

| Figure 37.—Mounted Forest Service ranger, Lorenzo Jared, on Green Ridge, Bald Mountains, in French Broad District, Pisgah National Forest, using field glasses to look for signs of smoke of forest fires. Spot is near Hot Springs, N.C., and Tennessee State line, in spring 1930. (NA:95G-238056) |

'Home-Grown' Rangers Do Best

How were the mountaineers persuaded not to burn? According to an early ranger, "it took a great deal of educational work with lectures at schools, moving pictures, and literature to overcome this practice." [60] The effort was a gradual one which evolved as a system of trust developed between the Forest Service and the mountain people. This system was often founded upon the selection and placement of rangers and forest technicians who had grown up in the mountains and knew them well. As the Forest Service Use Book of 1915 states, "The most successful rangers are usually those who have been brought up in timber work or on ranches or farms, and who are thoroughly familiar through long residence, with the region in which they are employed." [61]

A classic example of a local resident who became an outstanding ranger was W. Arthur Woody, native of northern Georgia, who started as a laborer in 1912 and became a district ranger there July 1, 1918. He retired in 1945. Known for his accomplishment of restocking the forest with deer and protecting wildlife, Woody was also renowned for his ability to get along with the mountaineers of his home. Woody enlisted local boys to help watch for and fight fires and resorted to his own methods of punishing incendiarists. His sons, Clyne and Walter, who also became foresters, as did a nephew and grandson, tell the tale of Woody tracking a fire-setting turkey hunter with a bloodhound, jailing him, and then returning him to the scene of the fire, whereupon the hunter finally confessed. [62]

Ranger Nicholson, of Rabun County, Ga., also employed a bloodhound. Former Regional Forester J. Herbert Stone remembers "Ranger Nick's" special fire prevention program:

One of the firebugs whom Nick had had his eye on up in that area, Rabun County, had been setting fires each year in the spring to get the country in shape for his stock. The year after the bloodhound's reputation had gotten around, a friend of his asked if he's going to burn the woods that year and he says, "No sir, not me," he says, "I don't want any bloodhound tearing the seat out of my britches." The result was that the fire record for that particular drainage improved tremendously. [63]

Early rangers and foresters hoped, by example, not only to stop the deliberate burning but to encourage the local inhabitants and timber concerns to practice enlightened silviculture and forest conservation as well. As W.W. Ashe has written, "stimulating private owners . . . in developing and applying methods of management" to cutover lands was one of the main purposes of acquiring eastern forests. [64] Evidence suggests that this campaign may not have been so successful as the one against fire.

|

| Figure 38.—Lorenzo Jared, French Broad District Ranger, Pisgah National Forest, N.C., talking over field telephone at Butt Mountain Lookout near Tennessee State line, spring 1930. (NA:95G-238057) |

Throughout the South, the lumber industry as a whole declined after 1909, as small, portable sawmills replaced the large, stationary mills. Many once thriving mill towns had been abandoned as the forests nearby were cut over. In Georgia, for example, the number of lumber mills declined by two-thirds between 1909 and 1919. [65] In North Carolina, over the same decade, the number of lumbering establishments did not decline, but the number of wage earners employed in lumbering and the timber products industry declined by nearly 25 percent. [66]

Logging, of course, continued on National Forest land, managed with an eye toward preservation and profit, sometimes on a large scale. The Carr Lumber Co., for example, extensively logged the Pisgah Forest under a 20-year contract which had been signed by Louis Carr and the Vanderbilts in October 1912. However, National Forest timber sales generally favored small concerns and individual operators. Many such sales were for fence posts, crossties, and tanbark, and in the early years were often made for under $100. [67]

|

| Figure 39—William Arthur Woody, a real-life legendary Forest Service figure in North Georgia all his adult life. Native to the mountains, he was the senior ranger on the Toccoa and Blue Ridge Districts, Cherokee and Chattahoochee National Forests, from 1918 to 1945. This is an April 1937 photo. (NA:95G-344061) |

Heavy Timber Cutting Continues

The influence of the Forest Service in controlling timber cutting on private land was less decisive. Certainly, in Kentucky, where no Federal purchases were made until 1933, heavy timber cutting continued throughout the 1920's, partly because many stands in eastern Kentucky did not become really accessible, or economically feasible to log, until that period. In areas where the National Forests had been established, in Tennessee, Georgia, and North Carolina, large scale destructive lumbering continued. Forester William Hall noted in 1919:

In most of the larger timber operations in the Southern Appalachians, there has been no change in former methods of cutting except to make the cutting heavier as a result of higher lumber prices. [68]

When the Weeks Act was passed, considerable animosity existed between many local lumbermen and Government foresters. To some extent this animosity can be attributed to the ideological and practical differences between lumbering and forestry which persisted, despite the teachings of Carl Schenck and Austin Cary. As Forester Inman Eldredge stated in his reminiscences of early Forest Service days, many foresters had little experience in using the woods and disparaged those who did:

You produced the timber and cared for it, and then you turned it over to the roughnecks to cut it up and ship it around. There wasn't any science or art to it... [69]

Reciprocally, lumbermen regarded early forestry as frivolous and foolish, in Inman's words, "a parlor game." Inman felt that bad feelings between lumbermen and Pinchot's foresters had been created by the foresters' intense, but sincerely expressed, propaganda against the "timber barons." [70]

Certainly, Andrew Gennett resented the picture he felt was painted of lumbermen as "crooks and rascals," who had "wasted and devastated the vast areas of the forests in the United States." [71] In 1926, Gennett, in cooperation with Champion and Bemis Lumber, bought up a vast acreage in western Graham County, N.C., from an English syndicate, and continued lumbering in his new operations in Clay County, N.C.; Beattysville, Ky., and Ellijay, Ga. [72] Throughout the 1920's, lumbering companies, such as Champion, Sunburst, Andrews, and Hutton and Bourbonnais, continued to clearcut and "high-grade" (cull) huge tracts, many of which, once depleted, were sold to the Forest Service in the mid-1930's.

|

| Figure 40—A dramatic scene of devastation on the slopes of Mt. Mitchell, N.C., after destructive logging and numerous resulting fires, in June 1923. This was typical of the Southern Appalachians then. (NA:95G-176379) |

Knowledge that the Forest Service would eventually buy their lands may have dissuaded some companies from practicing sound silviculture. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1920's, the relationship between the Forest Service and the lumber companies was improving. The lumbermen were beginning to trust the motives of the Federal foresters and were learning to turn Federal purchasing to their advantage. Gennett never cut his large tract in western Graham County, N.C., but sold it to the Forest Service in 1936 and 1937 for the unusually high price of $28.00 per acre. The 19,225-acre tract, containing some of the largest and most varied "virgin" timber in the Southern Appalachians, was steep and inaccessible, and, thus, too costly for Gennett to log. In 1936, 3,800 acres of the tract was set aside as the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest (since enlarged and now called Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness), which the Forest Service pledged to protect as a place of inspiration and beauty. [73]

Federal land acquisition in the southern mountains had an initial, and continuing, effect on the tax base of all counties in which lands were purchased. Since all lands passing into Federal ownership were no longer taxable, a given county's property tax income was reduced by varying percentages. However, the Weeks Act provided that 5 percent of the receipts from all timber sales on National Forest land within a county went to its treasury for schools and roads. Verne Rhoades, forest examiner, noted in his February 1912 report on the Unaka Purchase Unit that:

The question of taxation bothers many of . . . the people, especially the smaller owners, who think they will have to meet higher taxes when the land purchased by the government is removed from the total acreage of assessable property. . . [74]

|

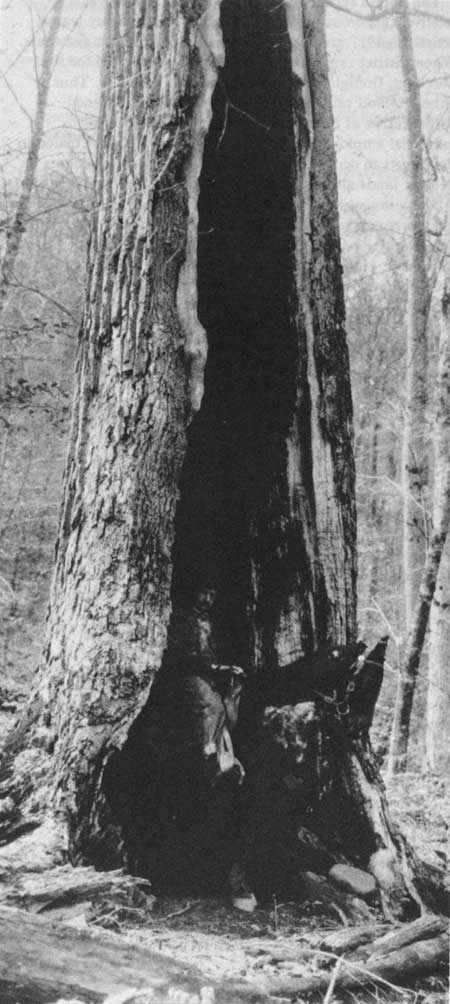

| Figure 41.—This huge burned-out yellow-poplar tree, a casualty of repeated forest fires, was long found useful by campers for shelter. Its size is indicated by man on horseback. Photo was taken on Little Santeetlah Creek in Unicoi Mountains, N.C., near Tennessee State line, in March 1916. This ares is now part of the Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness (formerly Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest) in the Nantahala National Forest. (NA:95G-27294A) |

County Rebate Raised to 25 Percent

The National Forest Reservation Commission considered the issue in 1911, and decided to study the extent to which local communities might be affected. In 1913 the group recommended that 5 percent be changed to 25 percent to provide greater compensation for the tax loss. Whether there was widespread local awareness of the possible loss of tax revenue from Federal acquisition in the early years is not apparent. Some counties undoubtedly suffered a loss by the change, although of those that did, the increase in small timber sales and Federal employment may well have balanced such loss.

The Forest Service, even in the earliest years, was a relatively generous employer. When the first survey teams arrived in 1911 and 1912, local men were hired as assistants. When district rangers arrived, men were recruited for fire watching, firefighting, trail building, and the like. Thus, although land sales to the Government often hastened outmigration as former landowners moved to towns for industrial employment, enough new jobs were also created in the forests to occupy both those who remained as tenants on Federal lands and those who lived on adjacent farms. [75]

Many rangers believed they had good relationships with the mountain people. Rangers and forest technicians often became community leaders and friends whom the local people learned to trust. J. Herbert Stone, who came to the Nantahala in 1930 as a technical assistant to the Forest Supervisor, testifies to the goodwill that the Forest Service felt had been built:

. . . so the relationships and the cooperation received from the people throughout the mountains was very fine. There were of course a few that would want to set fires and who would become provoked when they didn't get just what they wanted, but in the main the relationships between the people and the leaders of the communities was all that could be expected by the time I got there. . . [76]

In other ways, early Federal land acquisition and land management practices had a more subtle effect. The Forest Service introduced to the Southern Appalachians an element of culture and education which was basically northeastern and urban. In 1919 William Hall went so far as to claim:

. . . improved standards of living are coming in. . . Homes are kept in better repair. . . Painted houses and touches of home adornment are to be observed. Money is available for better food and clothing. The life is different. The people are different. Yet it must be remembered that these are the genuine Appalachian mountaineers who, until a few years ago, had no outlet for their products and none for their energies except the manufacture of moonshine liquor and the maintenance of community feuds. [77]

In spite of Hall's patronizing tone and reliance on the mountaineer stereotype to make his point, the Forest Service was providing leaders who began to earn the respect and loyalty of many local inhabitants and to effect lasting changes in the social and economic structure of mountain life.

Reference Notes

(In the following notes, the expressions "NA, RG 95, FS, OC, NFR (means National Archives, Record Group 95, Records of the Forest Service, Office of the Chief and Other General Records, Records of the National Forest Reservation Commission, 1911-1976, Series 27. "LA" means Division of Land Acquisition, General Correspondence, Exchange, Purchase, Donation, or Condemnations, Region 8. See Bibliography, IX.)

1. The National Forest Reservation Commission was composed of three Cabinet members, two Senators appointed by the President of the Senate, and two Congressmen appointed by the Speaker of the House. The first such Commission members were Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War; Walter Fisher, Secretary of Interior; James Wilson, Secretary of Agriculture; John Walter Smith, Senator from Maryland Jacob H. Gallinger, Senator from New Hampshire; William Hawley, Congressman from Oregon; and Gordon Lee, Congressman from Georgia.

2. NA, RG 95, Office of the Chief, Records of the National Forest Reservation Commission, Work of the National Forest Reservation Commission, 1911-1933, p. 2.

3. NA, RG 95, OC, NFRC, "Lands of Andrew and N.W. Gennett," June 19, 1911.

4. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys, Georgia. Andrew Gennett to W. L. Hall, May 28, 1912.

5. "The National Forests and Purchase Units of Region Eight," Forest Service unpublished report (Region 8, Atlanta, Ga., January 1, 1955), p. 30, copy in Regional Office.

6. Telephone interview with Walter Rule, Public Information Officer, National Forests of North Carolina, Asheville, N.C., September 19, 1979.

7. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examination, North Carolina, William Hall to R. W. Shields, January 19, 1912, Correspondence, Examination, North Carolina.

8. "The National Forests and Purchase Units of Region Eight," p. 3, Region 8 report, January 1, 1955, copy in Regional Office, Atlanta, Ga.

9. NA, RG 95, OC, NFRC, "Lands of Andrew and N. W. Gennett."

10. "Lands of Andrew and N. W. Gennett," p. 41.

11. NA, RG 95, OC, NFRC, Minutes of the National Forest Reservation Commission, February 14, 1912.

12. "The National Forests and Purchase Units of Region Eight," p. 41, Region 8 report, January 1, 1955, copy in Regional Office.

13. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Verne Rhoades, "Report on the Unaka Area in Tennessee and North Carolina," February, 1912, pp. 2-4, 10.

14. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Tennessee, 1913, W. W. Ashe to H. L. Johnson, August 14, 1913.

15. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Tennessee, 1912, Rowland F. Hemingway to the Forester, May 1, 1912.

16. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys, Georgia, 1911-15, Andrew Gennett to W. L. Hall, June 5, 1912.

17. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys, 1911-15, Thomas Cox, Survey Report, January, 1914; James Denman to Assistant Forester, July 21, 1914.

18. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys, 1912-14, E. V. Clark to the Forester, April 7, 1912.

19. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys, 1911-15, "Report on Establishment and Survey of Macon-Swain County Line Between the Shallow Ford of the Little Tennessee River and A Point on the Nantahala River."

20. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys, 1911-14, Mt. Mitchell, Diffenbach to the Forester, July 19, 1912.

21. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys, 1911-14, Mt. Mitchell, Thomas A. Cox to the Assistant Forester, August 17, 1914.

22. The Olmstead Lands, National Forests of North Carolina, Asheville, N.C., "Summary of Reports on Possession Claims on E. B. Olmstead Grants."

23. The Weaver Act of June 14, 1934, was passed solely to adjust the Olmstead claims (37 Stat. 189, 16 U.S.C. 4776). By reason of "long continued occupancy and use thereof," parties were entitled, with the authority of the Secretary of Agriculture and approval of the Attorney General, "to convey by quitclaim deed . . . interest of the U.S. therein." Olmstead Lands file, National Forests of North Carolina.

24. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Supervision, Smoky Mountains, 1911-15, W. W. Ashe, Memorandum for District Seven, February 18, 1915.

25. Jesse R. Lankford, Jr., "A Campaign for a National Park in Western North Carolina," p. 46. (See Bibliography, III.)

26. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, D. W. Adams to Forester Hall, September 1911; Rhoades, "Report on the Unaka Area."

27. William E. Shands and Robert G. Healy, The Lands Nobody Wanted (Washington: The Conservation Foundation, 1977).

28. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Nantahala, O. D. Ingall to the Forester, May 10, 1912.

29. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys, Georgia, Thomas A. Cox to Assistant Forester, February 13, 1914.

30. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, North Carolina, William Hall to D. W. Adams, September 15, 1911.

31. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Valuations/Examinations, W. L. Hall to R. C. Hall, July 17, 1911.

32. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, R. Clifford Hall to Assistant Forester, May 4, 1913.

33. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Purchase, Georgia, R. Clifford Hall to Assistant Forester, April 4, 1914.

34. NA, RG 95, Office of the Chief, Records of the National Forest Reservation Commission, Minutes of the National Forest Reservation Commission, November 1, 1911.

35. NA, RG 95, OC, NFRC, "Work of the National Forest Reservation Commission," p. 3.

36. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Supervision, Smoky Mountains, Verne Rhoades to Assistant Forester, August 6, 1913.

37. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, North Carolina, D. W. Adams to William Hall, September 2,1911.

38. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Mt. Mitchell, Robert J. Noyes, Forest Examiner, June 23, 1915.

39. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Georgia, J. W. Hendrix to Forest Service, July 17, 1914.

40. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Mt. Mitchell, Lennie Greenlee to W. W. Ashe, December 9, 1913.

41. NA, RG 95, OC, NFRC, "Work of the National Forest Reservation Commission," pp. 2, 3.

42. Shands and Healy, The Lands Nobody Wanted. (See Bibliography, I.)

43. "The National Forests and Purchase Units of Region Eight," p. 44, Region 8 report, January 1, 1955, copy in Regional Office.

44. Data on acquired tracts of the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests obtained from Basic Information Sheets, National Forests of North Carolina, Asheville. Pisgah was not the first, but the ninth National Forest east of the Great Plains.

45. NA, RG 95, OC, NFRC, "Work of the National Forest Reservation Commission," p. 12.

46. Clarke-McNary Act, 43 Stat. 653; 16 USC 471, 505, 515, 564-570.

48. Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the United States, Volume I, Population (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1923); and Fifteenth Census of the United States, Volume I, Population. 1933.

49. Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the United States, Volume VI, Agriculture (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922); and Fifteenth Census of the United States, Volume VI, Agriculture. 1933.

50. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," p. 185. A search through selected county newspapers of the region confirms this finding.

51. R. C. Nicholson, "The Federal Forestry Service," in Sketches of Rabun County History, Andrew J. Ritchie, ed., (n.p., n.d., c. 1948), p. 359.

52. Elwood R. Maunder, "Ride the White Horse." (See Bibliography II.) Although Eldredge was a supervisor on the National Forests of Florida, his remarks are applicable to the Southern Appalachian forests as well.

53. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Surveys/Examinations, Supervision, (Georgia), E. V. Clark to Forester, December 4, 1912; Supervision, (Cherokee), Henry Johnson to Assistant Forester, March 30, 1914.

54. Ashley L. Schiff, Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service. (See Bibliography, I.)

55. R. C. Nicholson, "The Federal Forestry Service," p. 360. (See note 51.)

56. Elizabeth S. Bowman, Land of High Horizon (Kingsport, Tenn.: Southern Publishers, Inc., 1938), p. 178.

57. "Cooperative Forest Fire Control, A History of Its Origins and Development Under the Weeks and Clarke-McNary Acts," USDA, Forest Service, M-1462, Rev. 1966, p. 26. Ralph R. Widner, ed., Forests and Forestry in the American States: A Reference Anthology, (Washington: National Association of State Foresters, 1968), pp. 203, 298, 309, 326-28. John R. Ross, "'Pork Barrels' and the General Welfare: Problems in Conservation, 1900-1920," p. 240. (See Bibliography, III.)

58. Schiff, Fire and Water. p. 17. (See note 54.)

59. NA, RG 95, OC, NFRC, Minutes of the National Forest Reservation Commission, April 8, 1920.

60. Nicholson, "The Federal Forestry Service," p. 360. (See note 55.)

61. USDA, Forest Service, The Use Book, 1915 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1915).

62. Interview with Clyne and Walter Woody, Suches, Ga., July 12, 1979.

63. Taped interview with J. Herbert Stone for Southern Region History Program, November 22, 1978. Made available by Sharon Young, Regional Historian, Region 8, Atlanta, Ga.

64. William W. Ashe, "The Place of the Eastern National Forests in the National Economy." Geographical Review 13 (October, 1912): 539.

65. Ignatz James Pikl, Jr., A History of Georgia Forestry, p. 17. (See Bibliography, I.)

66. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the United States Volume IX, Manufactures. 1919 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1923).

67. William L. Hall, "Influences of the National Forests in the Southern Appalachians," Journal of Forestry 17 (1919): 404.

68. W. L. Hall, "Influences," p. 407.

69. Elwood R. Maunder, "Ride the White Horse." (See Bibliography, II.) Cary was a Forest Service timber expert of the Schenck type.

70. Maunder, "Ride the White Horse."

71. Andrew Gennett, Autobiography, p. 164. Papers of the Gennett Lumber Company, Manuscript Division, Perkins Library, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

72. Douglas C. Brookshire, "Carolina's Lumber Industry," 162. (See Bibliography, II.)

73. Michael Frome, Battle for the Wilderness (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974), pp. 174, 175.

74. NA, RG 95, LA, Correspondence, Examinations, Verne Rhoades, "Report on The Unaka Area," p. 9.

75. William L. Hall, "Influences of the National Forests in the Southern Appalachians," Journal of Forestry 17 (1919): 404.

76. Sharon Young, Interview with J. Herbert Stone.

77. Hall, "Influences of the National Forests," 404.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region8/history/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2008