|

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81 |

|

Chapter IV

The Civilian Conservation Corps

In 1933, shortly after his inauguration as President, Franklin D. Roosevelt sent to Congress an urgent request for legislation to put unemployed young men to work in conservation jobs. FDR and others had been considering such a program for several months and when Congress passed the Emergency Conservation Work Act on March 31, 1933, they moved swiftly to get the program started. Just 5 days later Robert Fechner was appointed Director of Emergency Conservation Work to head the program. The first Civilian Conservation Corps camp was occupied in less than 2 weeks. By July, 300,000 men were in CCC camps all over the United States. [1]

At first, the Forest Service was the sole CCC employer; later it employed at least half of the men. Its camps were the first established and often the last closed down, some of them existing from 1933 to the end of the CCC in 1942. In contrast, other camps were usually dismantled and moved when they completed a project, often in less than a year. The Forest Service, which for years had been short of funds and manpower for tree planting, timber stand improvement, recreation development, building telephone lines, firefighting, road and trail building, and scores of related jobs on the Forests, had responded eagerly to the opportunity. Forest supervisors promised to put young men to work as soon as they could be recruited and brought to the forests.

Other agencies supervised significant numbers of CCC camps in the Southern Appalachian Highlands. One was the new Soil Erosion Service of the Department of the Interior, headed by Hugh H. Bennett, also created in 1933. Enrollees planted trees and shrubs to help hold the soil in place and built small dams to help lessen floods, mostly on private lands. These camps are difficult to trace, as they were often temporary, and moved to a new location when their work was completed. At the strong urging of a coalition of agricultural and forestry groups, Roosevelt transferred SES to the Department of Agriculture in March 1935 and had it renamed Soil Conservation Service. [2] The National Park Service had many CCC camps in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (16 in 1934 and 1935) and along the Blue Ridge Parkway. Other CCC camps worked on new State parks. The tasks performed by these camps were similar to those of the National Forest camps with the exception of timber stand improvement. The Tennessee Valley Authority provided work for men in about 20 camps in Tennessee and Kentucky building check dams and planting trees. TVA camps did their work both on TVA-owned lands and adjacent private land.

The Army, experienced in handling recruits, was given the job of processing the young men and operating and maintaining the camps. There was no drill or military training, but Army Reserve officers at first had to maintain discipline, arrange leisure-time activities, and provide suitable food, clothing, and shelter.

The CCC had an especially strong impact on the southern mountains and their people, so it is appropriate that the first CCC camp was located in an Appalachian National Forest. [3] As we have already seen, the CCC was indirectly responsible for the enlargement of the Southern Appalachian National Forests. The desire to find more places for the CCC to work in the East accelerated the process of acquiring more land for the forests, and $10 million in additional forest purchase funds came directly from the budget for CCC, Emergency Conservation Work. The CCC program was so successful and met so much approval nationwide that when emergency authorization for the program expired in March 1937, Congress passed new legislation continuing the program and giving it a more permanent status. Many hoped that CCC would continue after the Depression was over. As it turned out, CCC lasted only for a little over 9 years. Enlistment declined in 1941 as war industries attracted young workers. The CCC was disbanded starting in 1942, soon after the United States went to war.

Many Camps in Appalachia

CCC camps, usually with 150 to 220 enrollees each, were clustered thickly in the National Forests of Southern Appalachia. [4] The arrival of so many young men in the rural mountain counties created tensions, especially since the first CCC recruits were chiefly unemployed youth from the larger towns and cities of the States in which the camps were located. Accustomed to different standards of behavior and a different way of life, they were considered "foreigners" in the mountains, though many of them were still in their native State. Later this picture changed as the CCC recruited more young men from the neighboring farms and small towns. However, in lightly populated counties with lots of forest, local boys were often outnumbered in the camps. In the middle and late 1930's many boys came from heavily populated and urbanized New Jersey and New York, States with more unemployed youth than their forests could keep busy. These boys, many from tough big-city neighborhoods, found the southern mountains and people as strange as the natives found them.

Initially, CCC enrollees were unmarried, 17 to 21, unemployed members of families on relief or eligible for public assistance, not enrolled in school (the CCC was not a "summer job"), in good physical condition and of good character. The few World War I veterans accepted later usually had separate task-oriented camps. Both blacks and whites were enrolled, but were rarely in the same camp. The mountains had no black camps, because CCC administrators concluded large groups of young black males, would not be welcome. It was also more convenient to locate black CCC camps where there were lots of prospective enrollees.

Each camp had one to three reserve Army officers and technical personnel responsible for work supervision, including foresters, engineers, and experienced foremen. There were also a few local experienced men (L.E.M.), usually men who previously had worked for the Forest Service.

Hiring of technical personnel was at first under political control. The Project Supervisor for each camp was selected from a list of men approved by the local congressman. These jobs were much sought after since they paid quite well for the time, $1,200 to $1,800 per year. At first some project supervisors made more money than the local district ranger to whom they reported, but salaries were evened out later on. Eventually many supervisory personnel became Forest Service employees subject to Civil Service regulations. Even in 1933 and 1934 political approval for project superintendents did not cause serious difficulties. A former Forest Supervisor on the Nantahala recalled that because so many well-qualified men were unemployed, it was not difficult to select them from the congressmen's lists. This particular Forest Supervisor also remembers little difficulty in getting political approval for his own candidates for CCC jobs if there was no one suitable on the approved list. [5]

Many of the early enrollees did not work out because of the nature of most CCC work. An early inspection report from a camp on the Pisgah National Forest reported 41 "elopements" (unauthorized departures) from the camp during the late summer and early fall of 1933. The reasons given were the isolation of the camp and the hard outdoor work, unfamiliar to the former cotton mill hands sent in the camp's first allotment of young men, [6]

By 1936 there had been a shift to enrollees more familiar with outdoor labor. A survey made in January 1937 showed about one-fifth from farms and a third from small towns (less than 2,500 population). The shift seems to have been a natural and sensible one, and in part reflects the extension of relief and other welfare programs to some rural and semi-rural areas during the New Deal. There were no relief programs in most rural counties before 1933. [7]

One Project Supervisor at a National Forest camp observed another very definite change in the enrollees during the years 1933 to 1938. He wrote that during the first 2 years of the CCC most of the enrollees he worked with were young men in their early 20's who at one time had been employed. Some of them had useful skills, such as carpentry or truck driving. He thought that these early enrollees were willing workers who had been demoralized by unemployment, but could be organized to work well without extensive training.

By 1939 the CCC camp was receiving a different type of young man.

The majority of present day "Rookies" might be called products of the depression. From 16 to 22 years old, most of them quit school before completing the grammar grades, except for a few who attended vocational school from 1 to 3 years. Many admit they have loafed from 1 to 7 years and don't really know how to do anything. [8]

The effects of the Depression on school budgets and on the morale of young people had been devastating. For many enrollees, developing the physical strength and mental concentration necessary to do a full day's work was the most important part of their training in the CCC.

Many Enrollees Were Illiterate

For other enrollees the CCC provided an opportunity to acquire education. CCC education reports reflect serious efforts, usually successful, to teach illiterates the fundamentals of reading and arithmetic. For mountain boys especially, basic education filled a real need. One camp in Kentucky reported in 1940:

Due to the fact that practically all men enrolled in the company from seven local surrounding counties where educational facilities are limited, a major emphasis must be placed on Literacy Education. Twenty-five men enrolled in the company during the past year had never previously attended school. Sixty others were illiterate. [9]

Teachers for those in need of basic education were sometimes provided by Works Progress Administration (WPA) funds; sometimes other enrollees served as instructors. The use of enrollees as teachers was possible because there was a wide variation in educational background among the young men. In 1939 a camp near Morehead, Ky., reported sending eight young men to Morehead State College. Four enrollees were attending the local high school. [10]

The education the boys needed was not always available. The educational advisor from another camp in Kentucky reported that 76 men in his company had completed the 8th grade but no high school instruction was available. He was tutoring 11 men whom he classed as "semi-literate." [11]

Academic classes were not the most important part of the CCC educational effort. A nationwide education report for 1937 stated that about 60 percent of the classes in CCC camps were vocational because ". . . job training and vocational courses were the most popular in the camps . . . . and had the strongest holding power." [12] Only 33 percent of enrollees nationwide attended academic classes.

|

| Figure 69.—Camp Woody (F[Forest Service]-1), first Civilian Conservation Corps camp in Georgia, at Suches, Chattahoochee (then Cherokee) National Forest, in 1934. (Photo courtesy of Milton M. Bryan) |

Work Projects Under Forest Service

The Forest Service was responsible for job training related the work projects. The camp Project Superintendent was responsible for training in each camp. Forest Service staff, especially district rangers, were instructed to help camp supervisory personnel learn to use the education method recommended by the Forest Service. This method, generally, was to break each job into a number of simple steps and then coach the enrollees through the task step by step until they understood how to do it. [13]

A carefully prepared little pamphlet, "Woodsmanship for the CCC," was printed by the Forest Service and usually issued to each enrollee. [14] It went through a number of printings and was always in demand. "Woodsmanship" explained clearly, with many illustrations, how to use an axe or crosscut saw safely, and how to recognize potential hazards such as poison ivy. Other materials were developed to teach enrollees the basics of firefighting, Always the emphasis was on safety.

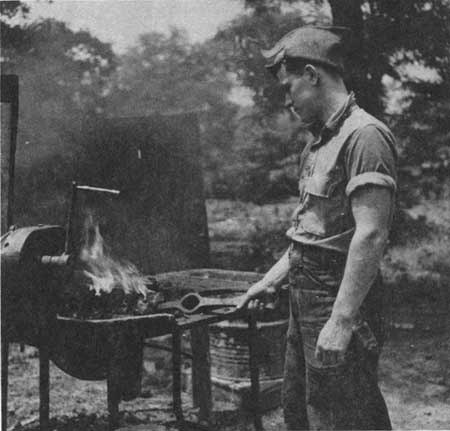

CCC boys were given some training and valuable experience as truck drivers, rough construction workers, operators of road and trail-building machines, cooks, and tool clerks. Some received special training as truck mechanics. Young men also developed leadership skills as leaders and assistant leaders of work groups. In the later years of the CCC many of the Forest Service technical personnel supervising CCC enrollees were former enrollees themselves.

A 1939 report from a camp in Tennessee listed the jobs that former enrollees reported that they had obtained as a result of training acquired in the CCC. These included filling station operator, skilled foundry worker, laborer, many truck drivers, mechanic, grocery store helper, railroad worker, sawmill hand, auto assemblyline worker, rock crusher operator, clerk in a laundry. [15] In come cases references from project supervisors helped former "Three C-ers" to get jobs by assuring prospective employers that they were honest and hard working. Job placement was important since CCC enrollees could remain in the Corps for a limited time only, 6 months to 2 years.

Pay for CCC enrollees seems very low by present-day standards—$30 per month. This limited amount would buy many necessities in the 1930's, when a loaf of bread cost 5 cents and a quarter would often buy 10 pounds of potatoes. For these young men $30 plus food, clothing, and shelter seemed a reasonable wage. Regular enrollees were given $5 per month for spending money; the remaining $25 was sent home to their families. In this way many became breadwinners for parents and younger brothers and sisters. Regular CCC enrollees at first signed up for a period of 6 months, after which they were allowed another term. Later, they were permitted to continue in the Corps for 2 years.

In addition to their wages, CCC enrollees received food, clothing and shelter at the camp. [16] Records of weekly menus indicate that the CCC boys ate well. Certainly the quantities of food were planned to satisfy appetites developed by hard outdoor labor. The quality presumably was affected by the skill of the camp cook, but since fresh fruits and vegetables, milk, and meats were purchased from local merchants and farmers, quality and variety were available. Staples such as flour and lard came from Army Quartermaster Corps.

The camps themselves were usually roughly built collections of wooden buildings, often unpainted. One building, or sometimes a series of small cabins, provided quarters for the officers in charge of the camp, for the project supervisors in charge of work, and the camp educational advisor. The largest building in a camp would be the kitchen and dining hall, with a recreation room either in the same building or nearby. The boys were housed at first in tents, then in rough wooden barracks, sometimes with bathroom facilities attached. Some camps had separate bath houses. There would usually be several sheds for trucks, road machinery, and storage. The buildings were heated in winter by wood- or coal-burning stoves. Buildings at these camps hastily constructed of green lumber in 1933 were in bad repair by 1940, but other camps were more solidly constructed, especially later buildings built by the CCC boys for their own use. Some of the more permanent camps had classroom buildings and athletic fields for leisure time activities.

Weekly Recreation Visits to Town

Most of the camps were close enough to towns to permit weekly recreation visits. Such visits were welcomed by the boys and by local merchants as well. Theater owners could count on a good audience for the motion picture when the CCC came to town. Some camps were actually located on the outskirts of small towns like Hot Springs, N.C. Other camps in the most rugged mountain districts were almost inaccessible. In 1939 an inspector noted that one camp near Laurel Springs, N.C., was 18 miles from the nearest telephone. The camp was also without telegraph or radio communication. Consequently, he recommended the construction of a telephone line to be used for fire control and to obtain assistance in emergencies. [17]

A rough idea of how many boys were affected by the CCC can be obtained from table 3, which gives some enrollment figures for 3 years and indicates as well the size of the CCC at its beginning (1934), peak enrollments at the height of the program (1937), and declining enrollments (1941). Declines were not so great for the Southern Appalachian States, especially Georgia and Kentucky, as they were in some areas of the country, but by the end of 1940 there were fewer camps and the remaining ones were below strength. [18]

Table 3.—Civilian Conservation Corps: Numbers of Residents and Nonresidents Enrolled in Camps in Each of Five Southern Appalachian States; Residents of These States Enrolled in Other Regions, 1934, 1937, 1941

| State | 1934 | 1937 | 1941 |

| Kentucky | |||

| Total residents enrolled in CCC camps (nationwide) | 4,495 | 5,571 | 5,414 |

| In Far West (beyond Great Plains) | 1,068 | 669 | 587 |

| In Appalachians | 820 | 1,224 | 660 |

| In other regions | 2,607 | 3,698 | 4,167 |

| Out-of-State residents in Kentucky Appalachian camps | 0 | 725 | 740 |

Tennessee | |||

| Total residents enrolled in CCC camps (nationwide) | 5,779 | 7,649 | 6,831 |

| In Far West (beyond Great Plains) | 0 | 43 | 827 |

| In Appalachians | 1,086 | 2,282 | 1,994 |

| In other regions | 4,691 | 5,324 | 4,010 |

| Out-of-State residents in Tennessee Appalachian camps | 3,248 | 126 | 143 |

North Carolina | |||

| Total residents enrolled in CCC camps (nationwide) | 6,820 | 8,542 | 6,219 |

| In Far West (beyond Great Plains) | 0 | 116 | 118 |

| In Appalachians | 3,839 | 1,355 | 684 |

| In other regions | 2,981 | 7,071 | 5,417 |

| Out-of-State residents in North Carolina Appalachian camps | 448 | 1,306 | 561 |

South Carolina | |||

| Total residents enrolled in CCC camps (nationwide) | 3,802 | 6,258 | 4,466 |

| In Far West (beyond Great Plains) | 0 | 192 | 185 |

| In Appalachians | 588 | 603 | 452 |

| In other regions | 3,214 | 5,463 | 3,829 |

| Out-of-State residents in South Carolina Appalachian camps | 0 | 241 | 158 |

Georgia | |||

| Total residents enrolled in CCC camps (nationwide) | 6,899 | 6,654 | 6,556 |

| In Far West (beyond Great Plains) | 0 | 381 | 1,143 |

| In Appalachians | 2,359 | 776 | 565 |

| In other regions | 4,540 | 5,742 | 4,848 |

| Out-of-State residents in Georgia Appalachian camps | 184 | 96 | 124 |

Source: National Archives, Washington, D.C., Record Group 35, Records of the Civilian Conservation Corps, Station and Strength Reports.

Two examples serve to illustrate further the impact of the CCC on the young enrollees. In 1934 a young Tennesseean, B. W. Chumney, enrolled. He intended to go to college later, but needed a job to earn expenses. However, his temporary job became a career. He remained on the Cherokee National Forest until his retirement in 1977. For the first 7 years he was employed by the CCC, though his duties in timber management and fire control remained similar when he was shifted to regular Forest Service employment in 1941.

Chumney participated as a fire dispatcher in the application of many new firefighting techniques, from the use of radio dispatching in the 1930's to helicopters and flying water tankers in the late 1960's and early 1970's. During his career he saw the Cherokee National Forest grow from a patchwork of eroded, cutover slopes to the magnificent and valuable stands of timber that comprise much of the forest today.

The Cherokee became Chumney's hobby as well as his job. He is a recognized expert on the history of the forest and has devoted much effort to collecting information about it. A staunch believer in Forest Service management practices, Chumney has preached fire control, timber stand improvement, and careful timber cutting to his neighbors and acquaintances for more than 40 years. Practicing what he preached, he used his savings to buy timber land which he managed carefully according to the practices he learned in the Forest Service. [19]

For other young men, the CCC provided only a few months' employment in the outdoors, but often with much benefit. One case history from the "Summary of Social Values 1933-1934" tells the story of Johnny S., a North Carolina tenant farmer's son who spent 6 months in the CCC. Johnny's family lived in an isolated area. The children (Johnny was the oldest of 10) had little schooling and almost no contact with the world outside their family. Johnny learned to read and write a little at the CCC camp and developed enough skill in the woods to get a job near home when he returned.

The county welfare director concluded his report:

Johnny has been home for some time now and all reports from him are that he "is holding his head high." He helped his father make a crop this year and received a share of it for his own. He made a great deal of money and bought a secondhand car. The neighbors say that he takes the family to church every Sunday and is now helping them to see beyond the little road that stretches in the front of their door. [20]

Johnny returned to his native area and even to his father's occupation, tenant farming, but for him, as well as for those who found new careers through the CCC, the experience provided a widening of outlook and opportunity for new skills. Johnny's brief experience away from home, according to the County Welfare director, marked the change from boy to man.

These two examples illustrate the wide variety of young men who found employment in the CCC. Anyone, from a semi-literate squatter to the Forest Supervisor himself, may have been a "Three C-er." And, most important, this shared experience helped the Forest Service for many years to build trust and friendships in the mountains. As the generation that served in the CCC retires and dies, this nostalgic common bond is being lost.

Large Camps Close to Towns Cause Some Friction

Most CCC camps sent truckloads of young men into the nearest town once or twice a week for recreation, often a visit to the local movie theatre. The boys were usually free to wander about town and spend their limited pocket money in the stores. Sometimes they attended services at local churches, though often neighboring clergymen were invited to conduct services at the camps and there were official chaplains assigned to groups of camps. After 1937, when the CCC became a more permanent organization and increased its emphasis on education, some boys attended local high schools and, in a few cases, colleges. CCC boys were also taken on recreation trips to see local landmarks, and to other camps or nearby towns to play baseball games.

The degree of social impact a camp had varied greatly from place to place. Smaller, more isolated camps might go almost unnoticed except by those who were employed there or who did business with the camp. Larger camps, and those very close to towns, made their presence felt continually, sometimes with unfavorable results for all concerned.

The most notorious case was Camp Cordell Hull, Tennessee F-5, Unicoi County. [21] This camp illustrates most of what could go wrong. In spite of the many problems, however, the camp remained in use throughout the life of the CCC, since there was much work to be done in the area. The camp also had an unlimited supply of pure drinking water (often a problem at other camps) since it was located on the site of the Johnson City waterworks. Because of its convenient location, much of the time the camp housed two companies of CCC—about 400 young men.

During the period of most serious trouble, 30 to 100 of the regularly enrolled young men were local, from Unicoi or neighboring counties. Thirteen local skilled men were employed by the Forest Service as supervisors for various projects.

A routine inspection of the camp in January 1934 reported all was well and that relations with the surrounding community were "very favorable," but as the weather improved in the spring, conditions deteriorated rapidly.

According to the military men assigned to run the camp, the locals used it as a ready-made lucrative market for prostitutes and moonshiners. The camp commander blamed lax local law enforcement for the situation and refused to cooperate with the local sheriff when he came to arrest CCC enrollees at the camp.

Local people did not want drunkenness in the camp, but at the same time turning in moonshiners was against their custom. As a former county sheriff put it:

There is some in the [CCC] camp that sells liquor. I can throw a rock from my barn and hit one of them. . . . I am personally acquainted with him, and it would hurt his feelings if I said anything about it. [22]

It would appear that the situation was also exacerbated by factionalism within the camp, for when a formal complaint was filed against the Army officers in charge, one of the complainants was the educational advisor. The complaint alleged misbehavior of the enrollees and failure of the officers to cooperate with local law enforcement officials. Other complainants were four neighboring residents and the county sheriff.

When the Army investigator from Ft. Oglethorpe, Ga., came to sort out the situation in July 1934, evidence indicated that the Army officers and the sheriff were all to blame. Testimony he collected showed that the four local residents had been enraged by the remarks yelled at local women and girls by CCC boys driving past in trucks. They also complained that CCC boys had disrupted two church services.

The county sheriff reported two serious incidents. The first resulted from a fist fight at a "wiener roast" in Unicoi. A CCC boy pulled a knife, seriously wounding a local boy. The knife-wielder was arrested, but escaped from jail and was hidden by his friends at the camp for several nights until he could arrange to get away. The local boy was believed to have started the fight.

The other was a "highway robbery" incident. A Johnson City man had picked up three CCC boys who were hitchhiking. He had a jug of whiskey which he offered to share and apparently all four had quite a bit to drink. The complaint contended that the boys then knocked him out (they said the whiskey did it) and took his car, which was hidden near the CCC camp. The CCC boys claimed that the incident, while regrettable, was really far less serious. Feeling against the sheriff was running high in the camp at that time and the camp commander refused to let him search the camp for suspects.

The CCC enrollees and their commander were angered by what they perceived as the sheriffs "double standard"—arresting them for drunkenness, but ignoring the illegal whiskey sales which caused it. The sheriff blamed moonshining on "bad times" and said wherever men congregate they will manage to get liquor; to him it was a normal occurrence. [23] The citizens also testified that there had been some troubles with local girls who hung around the camp. As one neighboring resident put it:

It seems that all hours of the night they are out, and if I understand it right there has been quite a few girls that has happened with bad luck. That is a misfortune to our community. [24]

The people of Unicoi County seem to have been reluctant to assume responsibility for the behavior of their own citizens toward the CCC camp, expecting the Army to prevent serious trouble by disciplining the enrollees. The Army officers, on the other hand, had to try to control about 400 vigorous young men without using military discipline. It was a difficult task, certainly not made easier by the ready availability of moonshine whiskey and other distractions. It is not clear how the camp commander was to control their behavior when on leave.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the whole acrimonious affair was that no one wanted the camp removed. All the complainants agreed that it was "a good thing for the county." The sheriff even protested that the camp commander had tried to get him in trouble with the local merchants by refusing to let the boys go into Erwin, the county seat. (The commander did later let local enrollees take a truck to Erwin to vote against the sheriff.) The camp was considered beneficial because of its contribution to the local economy.

Testimony also was unanimous that the Forest Service had nothing to do with the enrollees' misbehavior and was not responsible for the trouble. The complaint was entirely against the Army. The Army investigator concluded that nothing further needed to be done, since the camp commander had already been replaced, and he hoped for better relations with local citizens. No further serious disturbances were reported from Camp Cordell Hull. The personnel changes and increased efforts to keep the boys busy after working hours helped to improve community relations.

Although the Forest Service was not held responsible for the CCC's drinking problem in this case, it appears certain that a few temporary local employees who could not resist the chance for easy money in the bad times were often directly involved in moonshine distribution. In many camps the whiskey was covertly brought in by local experienced men (L.E.M.) or technicians. District rangers tried to eliminate men who were habitually drunk or who sold liquor to the enrollees. As the Supervisor of the Cherokee pointed out to a trail building foreman he had been forced to fire:

Regardless of the excellent caliber of an employee's services, the Forest Service cannot condone drinking by its employees on the job and at CCC camps. Instructions have been repeatedly issued to all employees cautioning him in this respect. [25]

Even firing a local foreman who peddled moonshine on the side was not as simple an issue as it might seem. The Forest Service was committed to doing its best to relieve unemployment in the mountain counties. Forest supervisors and district rangers were very anxious not to have "outside" CCC enrollees push local men and boys out of the available jobs on the forests. If a man was fired, often he could not find a job. Many local men had been employed by the Forest Service before CCC was established and firing them gave the impression that they were being pushed out of work by the CCC. [26]

Though for obvious reasons documentation of the practice docs not exist, conversations with former district rangers and indirect evidence suggest that illegal stills were frequently overlooked as long as they did not cause fires and the owner did not harvest timber illegally to fuel his still. Such tolerance would maintain local goodwill and prevent trouble. Moonshiners may have been surprised by the ban on sales to CCC men.

Enrolling and employing local men contributed directly to the drinking problem. The more local men there were in a CCC company, the more connections they had to obtain moonshine. One company commander in Kentucky noted in 1935 that some men had to be discharged and others disciplined for over-indulgence. [27]

Both drinkers and sellers became angry about efforts to control the use of liquor. Moonshiners saw the CCC camps as one of the best places to get hard cash for their product, though both the Army and the Forest Service tried to discourage them. According to one report, when a camp first opened at Pine Ridge, Ky.:

. . . the Moonshiners used to come on pay day and ask the camp commander to collect their booze bills for them. When they were ordered off the grounds they got sore on everybody. [28]

While the liquor problem never disappeared entirely, it did become less serious in the later years of the CCC.

In the early years of the CCC, the Forest Service was troubled by the requirement that they release even the most satisfactory of the local experienced men after only 6 to 12 months of employment. Supervisory personnel were not subject to these time limitations, and this caused resentment. In 1935 the Forest Service secured the approval of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work to keep the L.E.M.'s employed indefinitely where they were needed. It had been pointed out that many of the L.E.M.'s were former part-time Forest Service employees who had depended for work on the forest for years. [29]

Best Enrollees Get Forest Service Jobs

The Forest Service was able to arrange regular jobs for outstanding enrollees as well. A 1937 report on jobs for former CCC enrollees stated that the largest number had found jobs as machine operators or truck drivers; the second largest category of regular employment was with the Forest Service. In January 1937 the Forest Service reported that a Civil Service position, that of junior assistant to technician, had been created just for the CCC boys. Those who placed highest in the exam filled the available positions. [30] The agency was able to reward the most competent and interested CCC boys with permanent good jobs. The promise of more permanent jobs for their young men greatly helped to build local support as well as high morale in the camps.

Another way in which the CCC sought to create good feelings among its neighbors was by various kinds of festivities held to celebrate the "birthday" of the CCC in April of each year. There was even competition to see which camp could hold the most original party. They often included a picnic, open house, tours of work projects, and entertainment by enrollees. Some camps used these parties to preach the message of fire control, since the CCC camps were heavily involved in firefighting. Other camps used the parties as recruiting devices, seeking to convince young men visiting the camp to join the CCC. The parties were well publicized locally.

At one such party, the "CCC Fox Chase and Barbecue" at the 200-man Camp Old Hickory, near Benton, Tenn., on April 5, 1938, 1,500 people from Reliance, Archville, Greasy Creek Caney Creek, Etowah, and Cleveland joined the families of Cherokee National Forest personnel to feast on barbecued beef and pork, with trimmings. A foxhound show judged by a prominent citizen drew 68 mixed entrants, but a planned fox chase was cancelled for lack of a fox. [31]

In 1938 Camp Old Hickory had been in existence for 5 years and local residents were thinking of it as a permanent fixture. They were certainly familiar with the work it had done. If a family from a neighboring town decided to picnic in the Forest, they would drive on a stretch of road built by the CCC, and use the rest rooms and picnic tables built by the CCC as well. The caretaker at the picnic ground would be a trained CCC enrollee. If a farmer adjacent to the Forest started a fire to burn brush, it would be reported by a CCC youth manning a fire tower. If the fire threatened to spread into the Forest, it would be extinguished by a CCC crew trained in fighting forest fires. And if the farmer had misjudged the wind, and the fire began moving toward his house or barn, he could call for help from the CCC fire crew. [32]

Major Work Is in Fire Control, Road, Trails,

Campgrounds

Much of the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps was related, directly or indirectly, to the control of forest fires in the mountains. [33] Ever since the first land acquisition in 1912, the Forest Service had been convinced that control of fires was essential to the improvement of the forests. This was contrary to local practices of burning to remove debris, encourage forage growth or kill insects and snakes. Though much of this deliberate burning had been stopped as a result of Forest Service educational efforts, mountain people were often careless with fire when they burned brush on their own land. Hunters, fishermen, and campers sometimes failed to put out their fires. Finally, arson as a form of malicious mischief or to get work was popular in some mountain areas. [34]

The existence of the CCC gave the Forest Service a pool of manpower that could be trained to fight fires and was quickly available when fire broke out. The final report prepared when the CCC was disbanded concluded that "During the nine and one quarter years of the Corps, CCC enrollees became the first line of fire defense." [35] All were given basic firefighting instructions and indoctrinated in the Forest Service dictum that fires should be prevented.

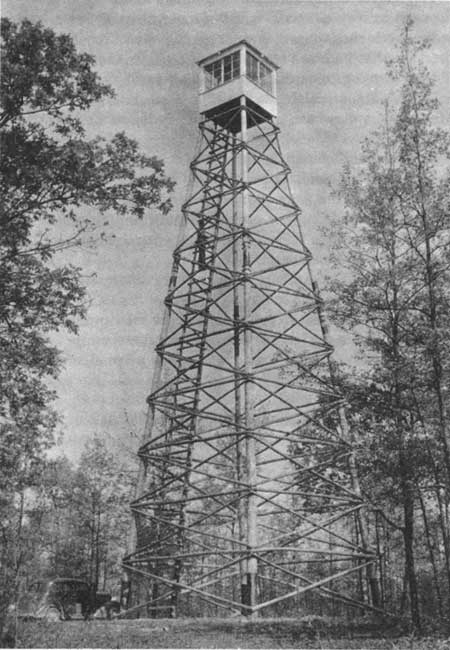

CCC youths built fire observation towers and manned them during the months of high fire danger. The towers, located high in the mountains in carefully chosen locations, made it possible to spot fires quickly and send in a fire suppression crew before they became large enough to cause serious destruction. Such towers were used until the mid-1960's when most of them were replaced by light patrol planes.

Fire towers had telephone and, later, radio connections to district ranger offices to report fires. The construction of telephone lines was another important CCC task. The telephone lines not only made reporting fires quicker, they also made possible the rapid assembly of firefighting crews where needed. Forest Service telephones were also available for use by local people in emergencies. This was much appreciated in areas where few people had private telephones. In some areas lines for private telephones were installed on the telephone poles put up by the CCC for Forest Service lines.

One of the biggest jobs undertaken by the CCC in the Southern Appalachian forests was road and trail construction. The enrollees built high-quality roads in some areas to open up the forest for timber harvesting or recreation, but many of the roads they built were of the type known as truck trails or "fire roads." These single-lane dirt roads could serve as firebreaks, but more important, they made it possible to bring truckloads of men and equipment quickly to the site of a forest fire. With the modern advent of new fire-control techniques, many of the old "fire roads" have been abandoned and others have not been maintained for lack of funds, but for 40 years the truck trails built by the CCC were a vital element in forest fire protection.

Because funds for road building had always been scarce in the mountain counties, the CCC roads were often an important benefit to small local communities and to isolated farmers. In Harlan County, Ky.:

The CCC built the road from Putney to the Pine Mountain Settlement School, primarily, of course, for fire protection. Its construction has resulted in rather heavy traffic consisting mostly of forest products finding their way to market. Before this road was built there was no means of getting out to the railroad. The School has been considerably enlarged and improved. [36]

By this time, 1941, the market for timber had recovered, and local residents in areas newly opened up by transportation improvement could get a good price for forest products.

|

| Figure 70.—Beulah Heights fire tower, a temporary structure of southern yellow pine with a 7- x 7-foot cabin, built by Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees. Daniel Boone (then Cumberland) National Forest, Ky., shown in April 1938. (National Archives: Record Group 95G-365411) |

Many Recreation Facilities Built

Although it was not their original purpose, the "fire roads" did much to open up the forests to recreational use by hunters and hikers who still gratefully use them today. The development, especially after World War II, of four-wheel-drive vehicles such as jeeps made these trails even more popular. CCC men also built trails for hiking, especially short ones to spots of particular natural beauty of interest, often providing bridges and steps for visitors also.

Valuable work was done by the CCC on the famous Appalachian Trail, the Maine-to-Georgia trail which follows the crest of the Appalachian Range. In the Pisgah National Forest about 60 miles of the trail were maintained by the CCC from 1933 to 1942. One section, from Hot Springs to Waterville, N.C., was relocated and 26.2 miles of new trail built. In the Chattahoochee National Forest about 100 miles of the trail were maintained, a new shelter was built, and a spring was improved. The CCC maintained 93.4 miles of Appalachian Trail in the Cherokee National Forest and constructed several new shelters for camping along the Trail. [37]

Since road building and automobile ownership were making the forests more accessible for recreation, the Forest Service put some of the CCC boys to work building campgrounds. A campground might include shelters, toilet facilities, picnic tables, fireplaces, parking lots, and water supply systems. The CCC also built and erected signs to direct visitors to the facilities and to points of interest. Bathhouses were built at some good swimming areas. The first caretakers and lifeguards for the facilities came from the CCC ranks.

In the newly purchased areas of the forests another CCC task was razing "undesirable structures," the cabins and outbuildings left behind by former owners or occupants, to prevent their use by squatters. In some cases windows and roofs were removed and the uninhabitable cabin was left to decay slowly. In later years only a few foundation stones and the base of a chimney remained to mark the site of a former mountain home.

The CCC was often referred to by the press as "Roosevelt's Tree Army." Tree planting was a much-publicized CCC activity. In the Southern Appalachian most of the tree planting was done by the TVA camps to control erosion and to beautify the margins of the lakes created by damming the rivers. The CCC planted seedling trees raised in TVA nurseries on private land if the owner promised to maintain and protect the infant forest. As woodlands planted by the CCC began to grow successfully, they gave needed encouragement to the TVA forestry program by showing that reforestation could work. [38]

There was no extensive planting of young trees in the National Forests of the Southern Appalachians. In most cases natural reproduction encouraged by the heavy rainfall could be relied upon to restock cutover lands within forests. [39] CCC crews did much timber stand improvement work, removing diseased or damaged trees and less valuable species to give more room for the development of desirable timber. Such work often greatly enhanced the value of a stand of trees, increasing the quantity and improving the quality of saleable timber. CCC boys helped combat deadly tree diseases, notably white pine blister rust. The crews learned to recognize and destroy the currant and gooseberry bushes which serve as an alternate host for the blister rust fungus. They also helped fight the bark beetle infestations which often severely damaged timber in the forests.

Federal administrators who placed emphasis on the educational role of the CCC sometimes argued that too much time was spent working. [40] Would it not be better for illiterates to spend more time learning to read? Whey should classes be confined to evening hours when the boys were often tired and ready to relax? The CCC position varied but work generally was considered by most important part of education for the CCC enrollee. "Book learning" definitely took second place.

|

| Figure 71—Hayes Lookout, Nantahala National Forest, N.C., a low wooden enclosed structure with a 6- x 6-foot cabin, built by Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees in 1939. (NA:95G-396050) |

|

| Figure 72.—A Civilian Conservation Corps enrollee tempering a pick head in an open forge at Lost Creek CCC Camp (F-26), near Norton, Va., in Clinch Ranger District, Jefferson National Forest, in June 1938. (NA:95G-367179) |

Benefits to Local Areas

Throughout the life of the CCC, there was continual debate about the quantity and quality of work accomplished. [41] Since CCC enrollees had to be trained for the work they performed, they naturally accomplished less than would a crew of already skilled laborers. Some Forest Service employees, especially project superintendents, argued that it would have been better to use the money spent on the CCC to employ local skilled workers to do the jobs performed by the CCC on the forests. In spite of efforts to employ as many local people as possible through the CCC, there was always some feeling that the CCC took jobs away from them. In truth, there is some doubt whether the Forest Service, Park Service, TVA, SCS, or State agencies that employed the CCC would have been able to get funds to have the same work performed by ordinary wage labor. CCC labor was cheap, even though the boys might not accomplish as much as skilled workmen.

The quality of work done by the CCC naturally varied from site to site; much depended on the vigilance and skill of the project superintendent. There were cases of loafing and of slovenly work performance, but these were balanced by examples of hard work resulting in well-built trails and buildings. The Forest Service and other "employing agencies" tried to encourage the enrollment of young men who would make good workers. They sometimes accused the local welfare and employment offices of enrolling the "worst first," because these young men appeared to be more in need of help. Many young men who enrolled in the CCC required job training and had little or no work experience. However, most of them learned the skills they needed and became good workers. Others left. Efforts were made to reward those who worked well with promotion to crew leader or to skilled jobs. Where there were large numbers of repeat enrollments, work output tended to improve because less training was required.

One advantage that the CCC had over many New Deal "make-work" projects was the the work was "real." Good project superintendents and district rangers made sure that the enrollees were told why the project they were working on was necessary. For example, they were shown how their particular truck trail or telephone line fitted into the plan for fire control in the district.

Although the CCC presence in the Southern Appalachians was sometimes disruptive, on the whole the program brought the mountains multiple benefits. The CCC employed thousands of local men, providing wages, education, and a sense of accomplishment. Thus, perhaps more than any other New Deal program, the CCC contributed much to human dignity in a time of dire economic need.

In addition, the CCC altered the landscape of the Southern Appalachian forests and parks. The fire towers, trails, roads, and campgrounds it built and the trees it planted, thinned, and protected were improvements that controlled fire, enhanced the forests' beauty, and made the mountains more accessible.

The overall impact of CCC camps on local communities, society, and culture can best be evaluated by a comparison. Even before the turn of the century mountain communities had been influenced by the temporary presence of logging or construction camps. Thus, adaptation to the presence of camps similar to those established by the CCC was not new. Railroad building, logging, and mining all brought large groups of "foreigners," chiefly young males, into the mountains. The impact of these groups on mountain culture and society was chiefly economic and often temporary. These is no evidence that the impact of CCC camps was any greater, or more lasting, but the program did ease conditions at a very critical time.

|

| Figure 73—A 26-year-old white pine plantation thinned and pruned the previous summer by Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees to encourage fast quality timber growth. Nantahala National Forest, N.C., in 1940. (NA:95G-396044) |

Reference Notes

(In the following notes, the expression "NA, RG 35" means National Archives, Record Group 35, Records of the Civilian Conservation Corps; "NA, RG 95, CCC" means National Archives, Record Group 95, Records of the Forest Service (USDA) Records Relating to Civilian Conservation Corps Work, 1933-42. See Bibliography, IX.)

1. Wayne D. Rasmussen and Gladys L. Baker, The Department of Agriculture (New York and Washington: Praeger Publishers, 1972), 34, 35; 89-91.

2. NA, RG 95, CCC, General Correspondence, Information, Emergency Conservation Work, What About the C. C. C.?, 1937, 1933-42, Information, Records of CCC Work, The CCC newspaper Happy Days is another source of stories about CCC, though few of these pertain to the region under discussion here.

3. Camp Roosevelt, near Luray, Va., in the George Washington National Forest, 120 miles from Washington, D.C.

4. The following account of the CCC is based on information in Record Group 35, National Archives. Investigation Reports and Education Reports for camps in the National Forests were used, and specific citations are given where necessary. John Salmond, The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-42: A New Deal Case Study (Durham: Duke University Press, 1967), Chapter 5, "The Selection of Negroes." Black camps were not welcome in most areas of the country and were limited in number, mostly in the Deep South.

5. Interview with B.W. Chumney, July 18, 1979, Cleveland, Tenn.; Interview with J. Herbert Stone.

6. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Neill McL. Coney, Jr., special investigator, Report on [CCC camp] N.C.F-5, Mortimer, N.C., Nov. 12, 1933.

7. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Education, June 30, 1937. "Federal Aid for Unemployment Relief," Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Manufactures, U.S. Senate, 72nd Congress, 1st Session, on S 174 and S 262 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1932).

8. James R. Wilkins, "The Charges We Watch," Service Bulletin 23: 7 (April 3, 1939). (USDA, Forest Service, Washington, D.C.)

9. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Education, Elbert Johns, Camp Kentucky F-13, McKee [Jackson County], Ky., Jan, 30, 1941.

10. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Education, Earl C. May, Camp Kentucky F-4, Clearfield, Ky. March 11, 1939.

11. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Education, Carl G. Campbell, Camp Kentucky F-9, Stanton, Ky. Oct. 21, 1941.

12. NA, RG 35, Report of Director of CCC Camp Education for year ending June 30, 1937.

13. NA, RG 95, CCC, CCC Personnel (Training).

14. NA, RG 35, CCC, USDA, Forest Service, "Woodmanship for the CCC," Washington, 1934, subsequent editions to 1940.

15. NA, RG 95, CCC, CCC Personnel (Training), Monthly Education Reports 1939, Camp Old Hickory, Tenn.

16. Menu and building descriptions are taken from Inspection Reports cited earlier.

17. NA, RG 35, Inspection Reports, Neill McL. Coney, Jr. to Assistant Director, CCC, Oct. 2, 1937, North Carolina F-7; Neill McL. Coney Jr. to Assistant Director, CCC, April 7, 1939, North Carolina NP-21.

18. NA, RG 35, CCC Station and Strength Reports 1933-42. The records of the following CCC camps were examined for this study: Kentucky: Camp Lochege, F-4, Morehead, Rowan County; Camp Woodpecker, F-9, Stanton, Powell County; (No name), F-13, McKee, Jackson County; Camp Bell Farm, F-14, Bell Farm, McCreary County; and Camp Bald Rock, F-15, London, Laurel County, all in Cumberland (now called Daniel Boone) National Forest: Camp Elkhorn, S-82, Hellier, Letcher County (Flat Woods area), and (No name), S-84, Crummies (Harlan County Game Refuge), both State camps; also several Tennessee Valley Authority camps. Tennessee: Camp Old Hickory, F-3, Archville (Benton), Polk County; Camp Cordell Hull, F-5, Unicoi, Unicoi County; Camp Evan Shelby, F-11, Bristol, Sullivan County; and Camp Turkey Creek, F-17, Tellico Plains, Monroe County, all in Cherokee National Forest; also several TVA camps. North Carolina: Camp Grandfather Mountain, F-5, Mortimer (Edgemont), Avery-Caldwell County; Camp Alex Jones, F-7, Hot Springs, Madison County; and Camp John Rock, F-28, Brevard, Transylvania County, all in Pisgah National Forest; Camp Coweeta, F-23, Otto, Macon County; and Camp Santeetlah, F-24, Robbinsville, Graham County, both in Nantahala National Forest; and Camp Meadow Fork, NP-21, Laurel Springs, Alleghany-Ashe County, Blue Ridge Parkway. Georgia: Camp Woody, F-1, Suches, Union County; Camp Crawford W. Long, F-7, Chatsworth, Murray County; Camp Lake Rabun, F-9, Lakemont, Rabun County; and Camp Pocket Bowl, F-16, La Fayette, Walker County, all now in Chattahoochee National Forest. (At the time, F-9 was in Nantahala, and F-1 and F-7 were in Cherokee National Forest.) South Carolina: Camp Ellison D. Smith, F-1, Mountain Rest, Oconee County, then in Nantahala National Forest, now in Sumter National Forest. (In this list, F stands for National Forest, NP stands for National Park, and S for State-operated camps.)

19. Interview with B.W. Chumney, July 19, 1979, Cleveland, Tenn. "Forest Fire Fighter" Cleveland Banner, Cleveland, Tenn., March 30, 1978.

20. NA, RG 35, 1933-1934, Appendix D—Case Histories, North Carolina, "Summary of Social Values."

21. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Tennessee F-5, Unicoi, Tenn.

22. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Tennessee F-5, Testimony of George W. Buckner, July 29, 1934.

23. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Tennessee F-5, Testimony of Sheriff M. F. Parsley, Erwin, Tenn. July 29, 1934.

24. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Tennessee F-5, Testimony of Alf T. Snead, Limestone Cove, Tenn. July 29, 1934.

25. NA, RG 95, CCC, Donald E. Clark, Forest Supervisor, to W.M. Felker, November 24, 1934, Camp Old Hickory, Tenn.

26. NA, RG 95, CCC, General Integrating Inspection Report, Region 8, 1937.

27. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Kentucky, F-9, Stanton, Ky., C.H. Mackelfresh to T.J. McVey, Sept. 17, 1935.

28. NA, RG 35, Investigation Reports, Kentucky. T.J. McVey to J.J. McEntee, Sept. 17, 1935.

29. NA, RG 95, CCC, Memorandum for Hiwassee Project Superintendents from J.W. Cooper, Sept. 14, 1935, Camp Old Hickory, Tenn.

30. NA, RG 95, CCC, News Release, March 6, 1937, Information, General 1933-42; Circular letter from A.W. Hartman, CCC Regional Office, Dec. 2, 1937, CCC Personnel (Training), Camp Old Hickory, Tenn.

31. NA, RG 95, CCC. This account of the "Fox Chase and Barbecue," April 5, 1938, is taken from local newspaper accounts found in the CCC Personnel Training file, Camp Old Hickory, Tenn.

32. NA, RG 95, CCC, Memo to District Rangers from Forest Supervisor, Cherokee National Forest, June 9, 1938, National Forest Development and Protection; Fire Reports to Forest Supervisor, Cherokee N.F., 1935; CCC Inspection Reports, 1933-42, Camp Old Hickory, Tenn.

33. The following account of work performed by the CCC is derived from records cited in notes 4 and 32.

34. John Salmond, The Civilian Conservation Corps 1933-1942. pp. 121-125; Michael Frome, The Forest Service, p. 20; Ignatz Pikl, Jr., History of Georgia Forestry, pp. 19, 28, 33. Summaries of work performed in the individual camps are found in the Inspection Report cited earlier.

35. NA, RG 35, "CCC in Emergencies."

36. NA, RG 95, CCC, Information, General, K.G. McConnell to G.T. Backus, In Charge, State CCC, May 23, 1941.

37. NA, RG 95, CCC, Information, Special, H.E. Ochsner, Forest Supervisor, Pisgah, Memo for Regional Forester, May 24, 1938. W.H. Fischer, Forest Supervisor, Chattahoochee, Memo for Regional Forester, March 16, 1938; P.F.W. Prater, Forest Supervisor, Cherokee, Memo for Regional Forester, May 13, 1938.

38. Marguerite Owen, The Tennessee Valley Authority (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1973), pp. 30-33.

39. NA, RG 95, CCC, Personnel (Training), P.F.W. Prater—Forest Supervisor, Cherokee National Forest, Memo on ECW Education (Conservation), April 27, 1937, CCC Camp Old Hickory, Tenn.

40. John Salmond, The Civilian Conservation Corps, pp. 47-54 and 162-168.

41. The following discussion of the CCC's accomplishments is based on the surviving records of the camps listed in table 3.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region8/history/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2008