|

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81 |

|

Chapter V

Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway

The New Deal decade of the 1930's introduced the Southern Appalachians to yet another Federal agency interested in land acquisition: the National Park Service. Compared to the Forest Service, the Park Service presence in the region is minor; yet it has engendered considerable public awareness and controversy. Although the Park Service operates several small parks, monuments, and historic sites in the Southern Appalachians, its presence is most visible in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway. [1] The creation of both parks, which occurred between 1928 and 1940, differed considerably from the creation of the area's National Forests.

The National Park Service was established in August 1916, as a result of a conservation campaign similar to the one leading to the Weeks Act several years earlier. Since the creation of Yellowstone Park in 1872, 13 National Parks had been created from the lands of the public domain. These had been under the jurisdiction of the General Land Office of the Department of the Interior, but some, like Yellowstone, had been supervised by the Army and others scarcely managed at all. Under the chief sponsorship of the American Civic Association, conservationists, civic groups, and legislators nationwide rallied behind the idea of scenic preservation, and promoted a separate agency to manage the parks on an active basis. [2]

The purposes of National Parks differ from those of National Forests (originally called forest reserves). The principal difference is that the parks stress preservation and the forests stress "wise use" of their natural resources. National Parks are areas of special national significance; many exhibit unusual natural scenic grandeur. The Act of 1916 which organized them under a National Park Service states that they were created "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." [3] In a National Park the forest is left essentially as it is; if trees mature, they are not harvested; if they fall, they are left to rot. [4] No timber harvesting, grazing by domestic livestock, mining, or hunting is allowed in National Parks, but fishing may be permitted, and individual dead trees that pose a hazard may be removed.

The National Forests, as is explained in Chapter VIII, are and have long been managed for a variety of public uses and needs. The so-called Organic Administration Act of 1897 provided for protection and management of the forests to insure favorable water flow and a continuous supply of timber for the needs of the Nation. In 1905 Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson emphasized that "all the resources . . . are for use" and directed the Forest Service to manage the forests so "that the water, wood, and forage . . . are conserved and wisely used . . . [for] the greatest good to the greatest number in the long run." [5] The first major uses of the forests were providing wood for local settlers and industries, and forage for grazing of local domestic livestock. Before long it was recognized that the forests were also important for public recreation activities and as habitat for diverse forms of desirable wildlife. Later on the Forest Service pioneered in setting aside special areas as wilderness. The principle of multiple uses, begun under Gifford Pinchot, first Chief of the Forest Service, thus developed. It is explained in detail in Chapter VIII.

Although certain land-management goals of National Parks and National Forests are somewhat similar—such as encouraging visitors and providing some facilities for them, encouraging and protecting wildlife, controlling dangerous fires, and preserving wilderness—the two agencies do have basic differences that can result in conflict at times.

The Forest Service and National Park Service have often been competitive. Their rivalry dates from Pinchot's successful negotiations for transfer of the forest reserves from Interior to Agriculture in 1905. The Forest Service opposed the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, believing that a separate agency was not needed to manage the country's most outstanding scenic areas, that the Forest Service could do the job just as well. Many such areas have been transferred from the Forest Service to the Park Service. A few National Monuments are still supervised by the Forest Service. Rivalry between the two services has continued to the present, rising in intensity during years when a merger of the two services or a large land transfer is proposed. [6]

The land acquisition policies of the two agencies differ as well. Units of the National Park System are created by individual acts of Congress; there is no legislation comparable to the Weeks Act authorizing general, ongoing land acquisition for the National Park System. In addition, until the 1960's, National Parks that had not been set aside from the public domain were acquired by State, local, or private agencies, and title was subsequently transferred to the United States. Thus, the lands for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park were purchased by specially formed park commissions in Tennessee and North Carolina; lands for the Blue Ridge Parkway were purchased by the States of North Carolina and Virginia. Some lands for the Parkway were transferred from the Forest Service.

Most important, eastern National Parks have been created through the power of eminent domain; unwilling sellers have had their lands condemned. In contrast, eastern National Forests have been created only with "willing buyer-willing seller" acquisitions. Since a National Forest is a multipurpose area to be used by man, taking all the land within a given forest boundary has not been considered necessary. A National Park, as an area of scenic preservation, usually must be wholly controlled to be preserved. Thus, acquisition of land for a park usually erases human enterprise and culture from the landscape.

|

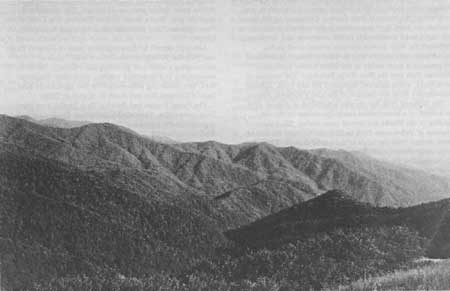

| Figure 74.—Great Smoky Mountains National Park, view from State Line Trail looking down Forney Creek watershed southeastward toward Little Tennessee River, in 1931. (National Archives: Record Group 95G-259049) |

Origins of Great Smoky Mountains National Park

After lying dormant for almost 20 years, the movement for a National Park in the Southern Appalachians came to life again during the winter of 1923-24. Since becoming first director of the National Park Service, Stephen T. Mather had favored an eastern park; for several years the Service had been considering possible sites. At a dinner at the prestigious Cosmos Club in Washington in December 1923, Mather, Congressman Zebulon Weaver of Asheville, and others resolved to press for a park in the Southern Appalachian region. In 1924, the Secretary of the Interior appointed a special Southern Appalachian National Park Committee to study potential sites. [7]

At the same time, pro-park groups were coalescing in the region itself. In Knoxville, Tenn., Willis Davis, manager of the Knoxville Iron Co., along with a small group of businessmen and attorneys, formed the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association for the purpose of raising interest in, and money for, a National Park and a road through the Smokies. Meanwhile, a group of North Carolina citizens reactivated interest in a Southern Appalachian park. In 1924, the State legislature created the North Carolina Park Commission for the purpose of securing a National Park in North Carolina. At first the North Carolina group preferred the site of Grandfather Mountain and Linville Gorge; however, after the national committee recommended the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia and the Great Smokies as the best sites for Appalachian parks, the North Carolina Park Commission shifted its focus to the Smokies.

The national committee was convinced of the suitability of the Smokies as a location for a National Park not only on account of its scenery but also its forests: "The Great Smokies easily stand first [in park sites] because of the height of mountains, depth of valleys, ruggedness of the area, and the unexampled variety of trees, shrubs, and plants." [8] It was the largest area of original forest remaining in the eastern United States. [9] Indeed, the "unexampled" tree cover had made the Smokies a loggers' paradise. Timber companies had been operating in the mountains for 30 years; in 1925, fully 85 percent of the area was timber company-owned. Although much of the land had been clearcut or culled, the steepness and remoteness of the area had delayed extensive logging in places; at mid-decade about one-third of the Smokies was judged to be still primeval forest.

Preservation of this unique forest was the goal around which an intense campaign began in 1925 in both Tennessee and North Carolina. In 1925 there was no Federal authority to purchase land for a National Park, as there was for a National Forest. Thus, wrote Mather, "the only practicable way National Park areas can be acquired would be donations of land from funds privately donated. [10] Each State set out to raise at least $500,000 toward initial land acquisition. Donations were sought from all levels of society, across both States. An earnest newspaper campaign began urging the importance of the Great Smoky Park. The appeals were to both esthetics and economics: preservation of the forest from inevitable destruction by the timber companies was urged; at the same time, the economic rewards of tourism to the area were assured. The park promised to be a tremendous boon to the mountain region, in the cash it would bring to businesses, in the employment it would offer, in the population increase the area would experience. [11]

Opposition to the creation of a National Park in the Great Smoky Mountains was vehemently expressed by a majority of the area's lumber companies. Indeed, the idea was anathema to them. They proposed instead the creation of another Appalachian National Forest: a compromise that would provide a scenic recreation site while allowing lumbering to continue.

Chief among the opposition spokesmen was Reuben B. Robertson, president of Champion Fibre Co. of Canton, N.C. Champion owned nearly 100,000 acres of spruce and mixed hardwoods in the very center of the Smokies which the company had bought from smaller companies about 10 years before. About 9,000 acres of the tract had been logged, but most was virgin timber. [12] Robertson began a publicity campaign via newspapers and pamphlets to counter the park enthusiasts. Although his primary motivation was to protect the economic interests of Champion, his arguments were also based on the value of scientific forestry. Since most of the Smokies were cutover or culled, he reasoned, they should not be left to the course of nature but managed under sound principles of silviculture. The Forest Service was, to Robertson, clearly the preferable land management agency. [13]

Support for Robertson's position was, if not widespread, at least strong. North Carolina lumber companies almost universally sided with Champion. Andrew Gennett, of the Gennett Lumber Co. of Asheville, agreed too, but proposed a compromise 100,000-acre park along the crest of the Smokies within the boundaries of a National Forest. [14] In Tennessee, the movement for a National Forest as an alternative to a park was led by James Wright, a landowner in Elkmont and attorney for the Louisville-Nashville Railroad. The movement was initially strong enough to defeat the first bill in the Tennessee legislature to buy a tract from the Little River Lumber Co.

Sentiment for a National Park, however, was ultimately stronger, although it is difficult to gauge the degree of public awareness of the park-vs.-forest issue. The newspapers, at least, carried the debate. Horace Kephart, of Bryson City, N.C., author of Our Southern Highlanders, argued against Robertson in an article in the Asheville Times of July 19, 1925:

. . . if the Smoky Mountain region were turned into a national forest, the 50,000 to 60,000 acres of original forests that are all we have left would be robbed of their big trees. They would be the first to go.

Why should this last stand of splendid, irreplaceable trees be sacrificed to the greedy maw of the sawmill? Why should future generations be robbed of all chance to see with their own eyes what a real forest, a real wildwood, a real unimproved work of God, is like?

It is all nonsense to say that the country needs that timber. If every stick of it were cut, the output would be a mere drop in the bucket compared with the annual production of lumber in America. Let these few old trees stand! Let the nation save them inviolate by treating them as national monuments in a national park. [15]

Indeed, Kephart reminded his readers, the Forest Service did not want a National Forest in the Great Smokies; the earlier purchase unit there had been dissolved and options to purchase relinquished. Others argued that a National Forest could not compare to a park in the tourist trade it would bring. As Dan Tompkins, editor of the Jackson County Journal, expressed the sentiment, "We have examples of national forests in Jackson and most of the other mountain counties, and if a single tourist has ever come here to see them, we've missed him." [16]

In the end, the arguments against lumbering, and for scenery, recreation, and tourism, were stronger. Local response to the fund-raising campaign was seemingly enthusiastic; by the end of 1925, several hundred thousand dollars had been pledged. Although a considerable amount of money was raised, the base of support for the movement is difficult to ascertain. As with the first Appalachian park movement, the second one was principally an urban, professional coalition, led by the business leaders of Asheville and Knoxville. The roles of publishers Charles A. Webb of the Asheville Citizen and Times and Edward Meeman of the Knoxville News-Sentinel were certainly key to the campaign's success. The movement was well organized, and its appeal was broader than that of the earlier park movement. Although there were undoubtedly small landholders and people employed in lumbering who opposed the coming of the park, their spokesmen were few; their opposition was overwhelmed by the momentum of the park idea.

First Tract Purchased In 1925

In 1925 the first tract of land for the Great Smokies park was purchased: 76,507 acres from the Little River Lumber Co. for $3.57 per acre. One-third of the $273,557 purchase price was paid by the City of Knoxville, two-thirds by the State of Tennessee. The tract was essentially the lands that had been optioned for purchase as a National Forest 10 years earlier. Most had been heavily cut, and lumbering was underway on the remaining acres. In fact, Col. W. B. Townsend, owner of the lumber company, sold the tract with timber rights for 15 years to all trees over 10 inches in diameter. [17]

On May 22, 1926, President Calvin Coolidge signed a bill passed by the 69th Congress authorizing Federal parks in the Blue Ridge and Great Smoky Mountains, all land for which was to be purchased with State and private funds. [18] The Great Smoky Mountains National Park was originally to be 704,000 acres. Once 150,000 acres were purchased, administration by the National Park Service would begin; once a minimum of 300,000 acres was purchased, the park could actually be developed.

The next 2 years involved a search for purchasing funds. Early in 1927, North Carolina appropriated $2 million for park land acquisition; Tennessee followed with an appropriation of $1.5 million. In 1928, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., offered $5 million from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Foundation on a dollar-for-dollar matching basis. Although finances remained tight, the Rockefeller grant assured that acquisition could begin on a large scale. [19]

Land acquisition for the Great Smoky Mountains Park took approximately 10 years, although certain condemnation suits were not resolved until the 1940's. The total area of the park contained more than 6,600 separate tracts. Over 5,000 were small lots that had been auctioned or sold for summer homes; almost all were in Tennessee. About 1,200 tracts were small mountain farms from 40 to several hundred acres in size; most were in Tennessee as well. The majority of the land was in a few large tracts held by timber companies, primarily in North Carolina. Among them were the Champion Fibre, and the Suncrest, Norwood, William Ritter, Montvale, and Kitchen lumber companies. Because most of the smaller tracts were in Tennessee, land acquisition there was more difficult and time-consuming. North Carolina park acquisition was almost complete by 1931; by 1934 only a 60-acre tract remained to be purchased. Tennessee on the other hand, was actively acquiring tracts as late as 1938. [20]

The authority for land acquisition was in the hands of the North Carolina and Tennessee park commissions. Verne Rhoades, former Forest Service officer, was executive secretary of the North Carolina Commission. At first the commissions were reluctant to take land by condemnation, but gradually they realized that it was necessary in some cases. The timber firms often asked prices the commission could not pay, and some of the smaller farmers were as resistant to selling as the timber firms. If an owner were particularly stubborn, he was permitted to sell his property at a lower price and become a lifetime tenant. The tactic was often used to determine which owners were clinging to their land out of genuine love and which were trying to drive hard bargains. [21]

Lumber Companies Violently Oppose Selling Lands

Some lumber companies expressed determined opposition to the purchase of their lands. In 1928 the Suncrest Lumber Co., having been asked to halt logging operations, and anticipating condemnation, challenged the constitutionality of the North Carolina Park Commission and its right to condemn. In a series of court battles the Commission won not only its right to force timber operations to halt, but also its right to condemn in State courts. In 1929, Suncrest closed its logging operations completely, but the tract was not purchased until 1932, when litigation over the price of the tract was resolved. The North Carolina Park Commission paid $600,000 for the almost 33,000-acre tract. [22]

The opposition of Champion Fibre Co. to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park at first had been fierce; however, after the North Carolina park appropriation of $2 million was passed, Robertson relented, and Champion subsequently suspended logging operations on its tract. Preliminary negotiations to purchase the property were begun in late 1929, but it soon became apparent that the park commissions and Champion placed vastly different values on the land. In January 1930 the Tennessee Park Commission began condemnation proceedings to acquire its share of the tract. Tennessee valued the 39,549 acres on its side at from $300,000 to $800,000; Champion claimed the acreage was worth between $4 million and $7 million. Champion based the figures on the incomparable quality of the area's spruce timber and the almost total dependence of the Canton mill on this spruce. Indeed, the Canton mill and rail lines had been built specifically to handle the spruce. Robertson's perspective in 1929 was that the loss of the spruce supply would mean an end to the sulphite mill. As he recalled later, in spite of the desirability of the park for the State and community, "we had a duty to our stockholders to protect their investment." [23]

In November 1930, a Sevierville jury awarded Champion $2,325,000 for the tract as well as $225,000 in damages to the Canton mill. Tennessee, outraged, threatened to appeal the case. Champion was not satisfied either; Robertson wanted $4 million for the tract. [24] Two months later he announced that Champion would resume logging on the Tennessee property; with that, the Tennessee Park Commission appealed the jury's decision.

The problem was finally resolved when National Park Service director Horace Albright called Champion and park commission officials to Washington. There, in spite of bitter personal disagreement between Robertson and Col. David Chapman of the park commission, a settlement was reached. Champion was paid $3 million for its 92,814.5-acre tract: over $32 per acre. In spite of Robertson's predictions, Champion's mill at Canton did not close. Over the course of the next decade the company perfected a process of making high-quality paper from pine fiber as a substitute for spruce. In fact, pine, available from the Piedmont, proved to be a cheaper resource than the Smoky Mountains spruce, and assured a much more profitable operation.

On the whole, the small farmers and lot holders, if not eager, were often willing to sell their land for the park. There were, of course, exceptions, some of whom were as resistant to the park as Champion and Suncrest. The lines of battle were drawn over prices: the disparities between values placed on land by the park commissions and those by the landowners were often wide.

The Cades Cove Settlement

Probably the most famous condemnation cases involved selected tracts in the Cades Cove area of Tennessee. Cades Cove, a wide valley surrounded by some of the Smokies' highest peaks, was a settlement of farms that had been passed down through families for several generations. John Oliver, who owned 375 acres in Cades Cove, absolutely refused to sell; condemnation proceedings began in 1929 but the case was not settled until 1935. The apparent source of Mr. Oliver's hostility to the park was a particular person on the acquisition team, who was subsequently replaced. Mr. Oliver was paid $17,000 for his farm, over $45 per acre. [25]

The Tennessee commission tried a series of tactics to persuade the Cades Cove opponents to sell. Ben Morton of Knoxville, whose father had been a respected physician in the area, was sent to Cades Cove as ambassador of goodwill. It was in response to Cades Cove opposition that the commission began allowing especially resistant oldtimers to remain lifetime tenants on their land if they sold at a lower price.

Other pockets of recalcitrant owners were the Elkmont and Cherokee Orchards areas of Tennessee, where some cases were not settled until the late 1930's. One especially well-known condemnation case concerned the 660-acre property of W. O. Whittle, not far from Gatlinburg. Whittle valued his land at $200,000; park estimators offered no more than $40,000. The case was in litigation until 1942, when a federal jury awarded Whittle $36,700, over $55 per acre. [26]

Other opposition to the park took the form of general disgruntlement with the Tennessee and North Carolina park commissions. In North Carolina, $51,000 in park funds had been lost in the 1931 failure of an Asheville bank. Over the next few years of the Depression, the expenditures of the commission often seemed extravagant. Protest was strong enough to effect change. In 1933, North Carolina reduced the size of the commission and appointed a new set of commissioners; in Tennessee, the commission was abolished and its duties transferred to the Tennessee Park and Forestry Commission.

Roosevelt Gets CCC Money For Park

In spite of these changes, the prices paid for land were often higher than anticipated and, even with the Rockefeller grants, the commissions ran out of funds twice. In December 1933, President Roosevelt secured $1,550,000 in CCC funds for the park, most of which went to pay for North Carolina lands. Several years later more funds were required. In 1937 Tennessee Senator Thomas McKellar attached to a bill appropriating money for lands in the Tahoe National Forest in Nevada, an amendment providing almost $750,000 to complete purchases in the Smokies. The bill passed in 1938. [27]

In general, the prices paid for park land were high, especially compared to prices paid for National Forest lands during the same years. Prices for large tracts in the Pisgah, Cherokee, and Nantahala National Forests during the 1930's averaged between $3 and $10 an acre. Even the incomparable "virgin" timber of the Nantahala forest's Gennett tract brought only $28 per acre. In the Smokies, Champion's land sold for $32 an acre. Companies other than Champion were paid well for their land. Suncrest's tract was settled in 1932 for over $18 per acre. In 1933, the Ravensford Lumber Co. tract, over half of which had been cutover, sold for over $33 per acre. In 1935 the large Tennessee tract belonging to the Morton Butler heirs was settled for over $15 per acre; the owners were outraged at the low price. [28]

To some degree, land values for the park were inflated by demand. The stated goal of buying all the land within the park boundaries undoubtedly encouraged some landowners, confident that the government would eventually buy, to hold out for higher prices. Built into some of the prices, of course, were the costs of litigation, damages, and delay. For example, when the Sevierville jury awarded a settlement to Champion Fibre, they included $225,000 for damages for the company's railroad and mill. [29] Nevertheless, considering that most of the Smokies' timberland had been cut and that Depression prices prevailed over the region, the discrepancies were large.

Land acquisition agencies were aware of the high prices being paid. In 1935 the Agricultural Adjustment Administration discussed cooperating with the Park Service in acquiring submarginal land in Haywood County, N.C., which could then be added to the park. The Forest Service also was enlisted to help. Samuel Broadbent, Supervisor of the Pisgah National Forest, felt the Forest Service could acquire a half dozen tracts along the Pigeon River at more moderate prices than the park commission, and pledged cooperation with the Park Service and AAA. [30] However, according to Roger Miller of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park headquarters, the Forest Service never acquired any land for the park. [31]

The Park's Effects on the Mountain People

In 1931, the headquarters of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established at Gatlinburg, Tenn., and the park was developed slowly. In 1936, after more than 400,000 acres had been acquired and turned over to the Federal Government, the Park Service assumed responsibility for land acquisition. In 1940 the park was dedicated by President Roosevelt.

Until most of the area within the park boundaries was consolidated, land management was fragmentary and difficult. Protecting the area from fires, vandalism, and hunting was the major management activity. It was particularly difficult to stop mountaineers from hunting on grounds they had used for that purpose for generations. Incendiary fires also plagued the first park rangers. Fire control improved over the decade with construction of fire towers and fire control roads by the CCC. During 1934 and 1935 there were 16 CCC camps active within the park, with over 4,000 men employed. [32]

In slightly more than a decade, there was an almost complete change in landownership within the park area. The timber companies either closed down, as Suncrest did, or resumed operations elsewhere. (The vast majority—85 percent—of the land was held by 18 lumber companies.) [33] Altogether, about 4,250 people, or 700 families, were affected by the creation of the park. [34] Most small farmers and their families in the Smokies settled on farms in adjacent parts of Swain, Sevier, and Graham counties, or in nearby villages. Gatlinburg, for example, which was a hamlet of only 75 people in 1930, grew to 1,300 residents by 1940, almost entirely as a result of park outmigration. [35]

In 1934 a survey of Tennessee families whose lands had been acquired for the park was undertaken by W. O. Whittle for the University of Tennessee Agricultural Experiment Station, to ascertain the impact of relocation on the lives of the people involved. Information was obtained on 528 families, and 331 were personally interviewed. The survey revealed that most families had relocated on adjacent land. Only 2.6 percent of the families moved to other States, and 22 percent to other counties. Fifteen percent retained temporary or life occupancy within the park boundaries. [36]

In general, the survey found that for the 331 families interviewed, movement from the area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park increased tenancy, decreased the average acreage held, and increased unemployment. Yet most relocated families also were closer to church, schools, and stores in their new locations, and found agricultural conditions more favorable. Overall, 54 percent of the families interviewed regarded the conditions of their former and new locations to be equal.

Land acquisition and outmigration continued at a trickle over the decades of the 1940's and 1950's, as boundaries were adjusted and most difficult cases settled. The pattern of outmigration was similar to that of the 1930's. In 1982 the park contained 515,000 acres or 208,600 hectares, about 805 square miles, with about 2,600 acres of inholdings yet to be acquired. [37]

Economic Boom Benefits Only a Few

The economic boom that park enthusiasts had promised was slow to arrive, and some would question whether it ever came at all. Although the annual number of visitors to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park increased over the years to over 3 million, the money left by them went only to a small portion of the local population. The Gatlinburg area, for example, virtually exploded in commercial acreage, number of businesses, gross business receipts, and residential subdivision, but the beneficiaries of this growth were few. Most of Gatlinburg's business district was owned for many decades by a few prominent families: the Ogles, Whaleys, Huffs, and Reagans. Thus, "the benefits of commercial land ownership, primarily in the form of contract rents, are flowing largely to a small group of local residents." [38] Others who invested in Gatlinburg were outsiders: either large, nationally based chains, in the case of businesses, or vacationers and subdivision developers, in the case of residential land. Meanwhile, for those who were dislocated by the park, the benefits of tourism were meager, if not nonexistent. [39]

The grievances against the park were sometimes specific, as in the case of many Swain County residents over the non-completion of a highway which the Federal Government promised to rebuild. Swain County is almost 82 percent federally owned: one half of the county is within the park, and half the Cherokee Reservation is in the county; much of the remaining land is part of the Nantahala National Forest. TVA's Fontana Dam, built in 1943, backed Fontana Lake halfway across the county. Several people who lived on park or TVA land relocated in the interstices of the National Forest. [40]

In 1940, even after the park was dedicated, park officials and park enthusiasts wanted to include one more major tract within park boundaries: almost 45,920 acres north of the Little Tennessee River in the area of Fontana, NC. [41] The tract belonged to the North Carolina Exploration Co., a subsidiary of the Tennessee Copper Co. It was traversed by North Carolina Highway 288, from Bryson City to Deal's Gap. Acquisition of the land would ease the administration of park regulations against hunters and poachers, and would help fire control. The value of the land, however, was exorbitantly high for the Park Service.

TVA Acquires Fontana Dam Site

During World War II, TVA acquired 44,000 acres of the tract for Fontana Dam. The lake created by the dam cut off Highway 288. TVA agreed to rebuild the road, but had insufficient funds to do so. Thus, a convenient exchange between Federal agencies occurred. TVA gave the remaining land to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. (At the same time, TVA transferred acreage south of the lake to the Forest Service.) The Park Service now had the regular boundary it desired, down to the shores of Lake Fontana, and in return agreed to rebuild Highway 288. Thus, TVA relinquished its responsibility for building a road, the Park got its desired land, and the people of the area were given a promise. [42]

In 1982 the promise was still unfulfilled. Only 6 miles of the road was built from Bryson City into the park. At one point construction was halted because of the legal question of the right of the National Park Service to build a nonaccess road through the lands of the North Carolina Exploration Co. In 1979 the road was not being built because of the environmental hazards it might bring. Excessive cutting and filling would be required on steep slopes; the mineral content of the soil would cause a dangerous runoff. Anakeesta, the predominant mineral, has been known to cause deadly pollution in mountain streams. [43]

The people of Swain County are not receptive to this reason for the Park Service's failure to rebuild its highway. They believe that their county has inadequate access from outside and, therefore, cannot participate in whatever benefits accrue from park tourism. In addition to access from without, residents have lost access to areas within the park that were homesites and farm sites. About 26 family cemeteries have been cut off from access by road; they can be reached only by boat across Fontana Lake, and then by foot or horseback up the mountains. Off-road vehicles are prohibited in the park. [44]

It was not the intent of the Park Service to eliminate the former culture of the Smoky Mountains region. In fact, the settlement of Cades Cove has been preserved as a historical area, with an operating grist mill and country store. Nevertheless, because the park has no permanent inhabitants and because the field and forests cannot be used as they formerly were, the park bears no sign of an active culture. The same can be said of the Blue Ridge Parkway, to be considered next.

Blue Ridge Parkway, a New Deal Project

It was not long after the establishment of National Parks in the Blue Ridge and Great Smoky Mountains that the idea developed to connect the Shenandoah National Park to the Great Smoky Park by a scenic mountain highway. Congressman Maurice Thatcher of Kentucky had promoted the idea as early as 1930. Since 1931 the Skyline Drive had been under construction in the Shenandoah National Park. The road had proved a welcome source of employment for the mountain regions particularly hard hit by the Depression; the idea of extending this roadway from the Shenandoah Park to the Smokies seemed logical, even inevitable.

The Blue Ridge Parkway was actually conceived during a meeting at the Virginia Governor's mansion in Richmond in September 1933. Although no single person can be credited as Parkway originator, Virginia's Senator Harry F. Byrd was instrumental in the inaugural phase of the project, convincing Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, and therefore President Franklin Roosevelt, of the Parkway's value. Official reaction to the proposed highway was immediate and almost universally enthusiastic. Within 2 months $4 million had been allotted for the Blue Ridge Parkway, and plans for its construction begun. [45]

The beginnings of the Parkway present a contrast to those of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Coming in 1933 at the Depression's depth and with the New Deal's optimistic launching, the Parkway passed immediately into the Federal domain. It was, from the beginning, not just a National Park but a relief project, and was supported and orchestrated from Washington.

With FDR's blessing, money for Parkway construction was allotted in December 1933 by the Special Board for Public Works under the National Industrial Recovery Act. This Federal funding was assured after the States had agreed to purchase the necessary right-of-way of 200 feet and deed it to the Federal Government. Secretary Ickes assigned the Parkway to the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, which was to cooperate with the Bureau of Public Roads in its construction.

Initial local reaction to the proposed highway was almost unanimously favorable. Hundreds of letters were received by Federal and State officials from mountain residents offering their land for rights-of-way, requesting that the Parkway be routed through a particular town or piece of property, or asking for employment in highway construction. One such letter received by North Carolina Congressman Doughton from a resident of Sparta pleaded for "us people that lives along the crest of the Blue Ridge . . . cut off from the outside world . . . We would be glad to give you the Right a way to get the Road." [46]

The Parkway was welcomed especially as a source of economic relief. Part of its appeal was undoubtedly its relative immediacy, but the boost anticipated was short-term, in contrast to the economic boom anticipated from tourism to the Great Smoky Park not a decade previously. The tourism the Parkway would bring in the future was secondary to the employment the Parkway would offer right away to absorb the labor surplus of the mountains. According to the Asheville Citizen, other Federal agencies and relief programs could not equal the Parkway in the quantity and type of economic assistance offered:

The National Industrial Recovery Act would do little for them [the mountain residents] because they had relatively few industries; the Agricultural Adjustment Act could not offer much aid because their small farms had no important staple crop; the Tennessee Valley Authority could offer little immediate help, if ever; the creation of Shenandoah and the Great Smoky Mountains National parks and a series of national forests had removed much property from the tax books and had halted the timber work which had employed thousands. Thus, a great local construction project, such as road building, appeared to be their only salvation. [47]

Opposition expressed toward the construction of the Parkway was scattered and feeble. Certain conservation groups registered concern about the highway. Nature Magazine in a 1935 editorial protested that the Parkway would ruin the landscape and allow careless dispersal of trash; Robert Marshall, who a few years later became Recreation Director of the Forest Service, expressed worries at a 1934 meeting of the American Forestry Association that the Parkway would destroy wilderness areas. [48] Certain owners of summer mountain cabins, threatened with the loss of their private retreats, protested the road. On the whole, however, in the middle of the 1930s the Blue Ridge Parkway was a much-applauded, happily anticipated regional gain. [49]

The selection of the route of the Blue Ridge Parkway absorbed nearly a year of bitter wrangling between North Carolina and Tennessee for Federal favor. The final choice of a route along the higher mountain ridge in North Carolina, by Grandfather Mountain, and by Asheville, to enter the Great Smoky Park at Cherokee, was made by Secretary Ickes in late 1934. Actual acquisition for the Parkway began shortly after the final route selection was announced. [50]

The National Park Service required that for every mile of parkway, 100 acres be acquired in fee simple, and 50 acres of scenic easement be controlled. The average width of the right-of-way strip was to be 1,000 feet, and no less than 200 feet. Although Virginia never accepted these requirements, for the most part North Carolina did. Both States had the power to condemn by eminent domain; in North Carolina, simply posting the Parkway's route through a given county at the county courthouse established the right to title. In Virginia, the acquisition procedure was the same as for other State roads. [51]

Altogether 38,000 acres in North Carolina and 23,500 acres in Virginia were acquired for the Blue Ridge Parkway. The Parkway deliberately bypassed existing communities; thus, for the most part, the land acquired was in the most remote and sparsely populated areas of the mountain counties. Many of the people whose land was affected lived in small isolated cabins or on meager subsistence farms. In some cases, area residents had never heard a radio. [52] The surveyors for the path of the Parkway often found the land as remote and inaccessible as had the early Forest Service surveyors 20 years before.

|

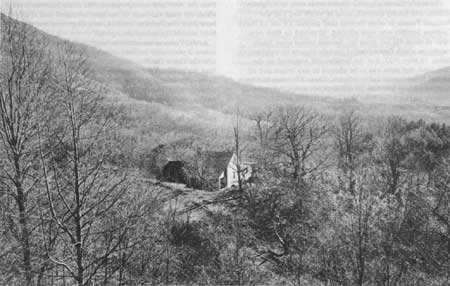

| Figure 75.—Tiny dilapidated log cabin, similar to many encountered on the right-of-way of the Blue Ridge Parkway and in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. This one was on lower slopes of Flat Top Mountain, between Troutdale and Konnarock, Va., in July 1958, near the present Mt. Rogers National Recreation Area, east of Damascus, near the Tennessee and North Carolina State lines. (Forest Service photo F-487199) |

Parkway Land Acquisition Proves Difficult

In both States, in spite of the eagerness that initially greeted announcement of the Parkway, acquisition of both rights-of-way and scenic easements proved much more difficult than anticipated. This difficulty was due partly to popular confusion and misunderstandings about what the scenic easement and right-of-way for a National Parkway imply. In the case of a right-of-way, title is held by the Park Service; in the case of an easement, the landowner continues to hold title but relinquishes to the Federal Government certain controls over the use or appearance of the land. In both cases, roadside development, commercial frontage, and access are strictly prohibited. Thus, a landowner selling a right-of-way or easement received no direct benefit from the Parkway, save the one-time payment for the land. Furthermore, there may have been a discrepancy between those who wrote the editorials proclaiming a county's eagerness for the roadway and those whose land actually lay in the Parkway's path. It was probably easy for a mountain county in 1934 to applaud the coming of the Parkway in general, but not so easy for individual mountaineers 2 years later to accept that their particular tract would be taken.

Although many residents were pleased to sell their mountain land at a time of economic deprivation, some counties had scores of condemnation cases during the acquisition process. Tales of mountaineers' fierce resistance to land sales echo those of Cades Cove in the Great Smokies. One owner, for example, challenged the constitutionality of the North Carolina law appropriating the purchasing funds; one refused to move a barn from the acquired right-of-way and had it sliced down the middle instead; one threatened a bulldozer with a double-barrel shotgun. Some landowners were ultimately able to avoid losing their land. As in the Great Smoky Park, several grants of lifetime tenure were given as exceptions to elderly people whose families had held the land for generations and who were especially resistant to moving. In addition, some summer homeowners were persuasive enough to have the Parkway re-routed around their tracts. [53]

It must be remembered that most landowners sold only a strip or corner of their land; except where the original acreage was small, losing a strip did not necessarily infringe on the privacy or coherence of a tract. Poor mountaineers obviously suffered more than large landholders. In some areas more than a strip of land was involved where special developments were planned along the 477-mile Parkway route: recreation sites for camping and picnicking; service areas for lodging, eating, and automobile service. For them, at least several hundred acres had to be acquired.

The effect of acquiring special development park areas on the lives of the people who had resided there suggests what some other mountaineers along the Parkway route experienced. Families forced to give up their farms were suddenly confronted with the necessity of finding new homes and in some cases, new employment. For some, the process of relocation was relatively easy; for others, relinquishing their land brought confusion and helplessness. Five of the special service areas became part of a Land Use Project funded by the Resettlement Administration in May and June 1936. The five areas totaled 5,300 acres, most of which was optioned for purchase by the summer of 1937. A total of 39 families had lived on the acreage and, with option for purchase, had moved on their own or were helped to relocate. [54]

The North Carolina special service areas were in Alleghany, Wilkes, and Surrey counties, none of which had had any National Forests or other Federal land project. Of the 13 North Carolina families who were affected, 10 moved on their own. Most of them did not move far. Several owned other tracts nearby on which they settled; 3 became tenants on neighboring farms. In May 1937, 3 of the families still remained on the park land, but none was to be allowed to stay longer and all needed Resettlement aid to relocate. These 3 families had been farming plots of less than 20 mountainous acres; their cash incomes averaged less than $100 per year. The families averaged 6 members; their housing was sub-standard at best. Although all were poorly educated and untrained, they were regarded by welfare workers as having "a tenacious and fighting spirit." None had ever been on relief before. [55] The 3 families wished to resettle on farms close to their current homes. They were expected to be paid between $4 and $10 per acre for their lands; all were expected to need help in finding land and employment.

The summary of proposals and recommendations regarding the people displaced by the park areas may speak for other mountaineers all down the Parkway route:

The majority of families living within the park areas were living on submarginal land, and most of the persons living there were the owners of the tract on which they lived. The families themselves felt that in selling their land they had done a service for the government. They are worried and at a loss to know the reason for the great delay in being paid, and the necessity for a relief status before they can get work in the park. In the majority of cases the only asset the family had was the farm on which they lived. They will receive so small a sum for their land that it will be impossible for them to continue as self-supporting citizens unless some aid is given. In many cases advice in buying new land is necessary in order that the family will not be influenced to buy land that will not meet their needs and on which they cannot improve their condition. [56]

In general, it appears that for the poor mountaineers whose lands were taken for the Parkway, compensation was meager and slow to arrive. Some may have felt they helped their Government, but they were confused and upset about the delay in payment for their land. For the poorest, dislocation seems to have necessitated relief payments and a welfare status. Even for those who profited nicely by their land sales, the long-term benefits may have been limited. Profits from sale of land with inflated values are often illusory when the seller tries to reinvest in comparable land. [57]

The Blue Ridge Parkway did, however, bring employment to the region, supplying numerous jobs from 1935 until World War II. Four CCC camps employing about 150 boys each were established along the route of the Parkway; the Emergency Relief Administration sponsored several building projects as well. Private contractors on the Parkway were required to use as much local labor as possible; laborers had to be recruited from the relief and unemployment rolls of the counties through which the road was built. It has been estimated that of all the hard labor the Parkway involved, only 10 percent was imported from outside the immediate region. [58]

Actual Parkway construction began in September 1935, almost 2 years after authorization, on a portion of the Parkway near the North Carolina-Virginia line. More than 100 men from the relief rolls of Alleghany County, N.C., were recruited. Eventually, local men were hired to help in surveying, land clearing, fence building, planting, erosion control, truck driving, and construction of recreation and service facilities. Wages were the minimum 30 cents per hour, which was generally far more than was obtainable elsewhere in the area.

As a long-term employer, however, the Blue Ridge Parkway served a limited role. After construction was completed, the Parkway continued to employ, and still does, local residents in the service areas, for maintenance, repairs, and grounds keeping, but the staff is not large.

|

| Figure 76.—View from Blue Ridge Parkway showing mountain farm home, and fields and forest lands encountered along the route. Forests were heavily culled, and many farm fields were worn out and returning to brush. This scene, taken in 1948, is on lower slopes of Sharp Top in the Peaks of Otter region of the Jefferson National Forest near Roanoke, Va. (Forest Service photo F-452145) |

Parkway Bypasses Mountain People

Aside from the initial money received for the sale of land and scenic easements, and the Depression employment it supplied, the Blue Ridge Parkway bypassed the people of the Southern Appalachians. The Parkway forbids roadside development and commercial establishments, minimizes access, avoids existing communities and arterials, and prevents new ones from encroaching. A visitor can travel the entire Parkway and, except for exhibit areas preserved by the Park Service, scarcely see a sign of the mountain culture the road has displaced. Like the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the land acquisition for, and the management of, the Blue Ridge Parkway have done little to preserve or enrich the culture of the Southern Appalachians.

Forty years later it is still important to recall the impact of the New Deal on the Southern Appalachian highlands. The coming of largescale lumbering had altered the economy and the landscape of the region in the years following the turn of the century. The alterations made by the New Deal were just as profound, but very different. Earlier change came from increasing exploitation of resources and people. The New Deal marked the first real attempt to protect them. However, New Deal programs were ultimately unable to change entirely the pattern of thoughtless exploitation of resources such as timber and coal. The people and the land benefited from the New Deal, but it was not enough.

In the mountains as everywhere in the United States, the New Deal brought agencies of the Federal Government directly into the lives of ordinary people for the first time. For the first time people were encouraged to think that Federal programs might solve their local problems.

The National Forests had been in the mountains for 20 years, but they had had limited visibility and impact. Much of the land purchased earlier was cutover timber land with few inhabitants. As the forests were expanded during the New Deal, they became more important to the economies of the neighboring counties and began to push aside some local residents. Forest expansion was only part of the large Federal land acquisition carried out by various agencies. The Park Service and the Tennessee Valley Authority in particular bought numerous small tracts of land from mountain people. The number and complexity of these land purchases guaranteed that many sellers would be left with a grievance against "the government."

The benefits of the land purchases are often more readily visible to those removed from the scene by time or distance. Today the economic development programs, electric power, erosion and flood control brought about by TVA have made an obvious contribution to life in the Southern Appalachian region. The Great Smoky Mountains Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway are national treasures enjoyed by millions of visitors every year. The National Forests have become increasingly important for outdoor recreation and as places where Appalachian hardwoods can grow for future generations. In the 1930's in mountain neighborhoods it was often easier to think of families displaced and rural villages gone than of the future benefits available to those who remained.

Although there were some problems and conflicts, the CCC generated more good will than any other Federal program of the '30s. Employment provided by the CCC was invaluable to many mountain families. Welfare programs could have a demoralizing effect on the mountain people, as Caudill points out in Night Comes to the Cumberlands. [59] But the CCC was not a "something for nothing" program. By encouraging work and learning, it provided a valuable antidote to the hopelessness the Depression had added to an area already beset with economic problems.

It is difficult to evaluate the impact of the growing recreation use of the mountains. The potential for enjoyment of the mountains was preserved and greatly increased by New Deal developments. Long frequented by the wealthy, mountain resorts became more accessible to the automobile-owning middle class. The park, parkway, and forest recreation provided are a blessing to those, often from urban areas, who use them; but they are a mixed blessing to mountain people. Tourist business can contribute to a local economy, but the contribution is rarely a large one, as many people of the region were to realize in the 1960's and 1970's. [60]

It was the Forest Service, with its emphasis on long-range production of a renewable resource, that contributed the most to the preservation of possibilities for the old mountain way of life. The lands it took over generally remained open for traditional uses such as wood gathering, hunting, fishing, and berrying. The Forest Service and the CCC together provided the best job opportunities for mountain men during the Depression years. The growing timber promised employment for the future as well.

Reference Notes

(In the following notes, the expression "NA, RG 83, FHA" means National Archives, Record Group 83, Farmers Home Administration (USDA). See Bibliography, IX.)

1. Other national parks in the Southern Appalachian region include the Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park, the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, and the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site in Greenville, Tenn.

2. Jenks Cameron, The National Park Service (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1922). William C. Everhart, The National Park Service (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972).

3. National Park Service Act, 39 Stat., 535.

4. Everhart, The National Park Service, pp. 184, 185.

5. James Wilson, Secretary, to the Forester, Forest Service, 1 February 1905. History Section files, Forest Service.

6. A detailed treatment of the rivalry between The National Park Service and the Forest Service is found in Allan Jarrell Soffar, "Differing Views on the Gospel of Efficiency; Conservation Controversies Between Agriculture and Interior, 1898-1938" (Ph.D. dissertation, Texas Tech University, 1974).

7. Jesse R. Lankford, Jr., "A Campaign for a National Park in Western North Carolina, 1885-1940," p. 48. Master's thesis, Western Carolina University, 1973.

8. Carlos C. Campbell, Birth of a National Park in the Great Smoky Mountains (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1960), p. 29.

9. Alberta Brewer and Carson Brewer, Valley So Wild: A Folk History. Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1975, p. 349.

10. Elizabeth S. Bowman, Land of High Horizon. Kingsport, Tenn.: Southern Publishers, Inc., 1938, p. 180.

11. Lankford, "A Campaign for a National Park in Western North Carolina," pp. 61, 62.

12. Carlos C. Campbell, Birth of a National Park in the Great Smoky Mountains. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1969, p. 92.

13. Lankford, "A Campaign for a National Park," p. 53, 55.

14. Lankford, "A Campaign," 53, 55.

15. Horace Kephart, The Asheville Times, July 19, 1925, cited in Bowman, Land of High Horizon, p. 188.

16. Jackson County (North Carolina) Journal, November 25, 1915, p. 2.

17. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, Chapter 4.

19. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, Chapters 5-9. See also Lankford, "A Campaign for a National Park."

20. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 70.

21. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 70.

22. Lankford, "A Campaign for a National Park," p. 82.

23. Elwood R. Maunder and Elwood L. Demmon, "Trailblazing in the Southern Paper Industry," p. 9. Forest History 3 (Winter 1960), Forest History Supplement No. 2.

24. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, pp. 84, 85.

25. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 98.

26. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 128.

27. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, Chapters 16, 17.

28. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, pp. 116-118.

29. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 84.

30. NA, RG 96, Records of the Farm Security Administration (USDA), Region 4, Correspondence of Director, Land Policy Section, Division of Program Planning, AAA, Letter from Paul Wager, Resettlement Administration, to Sam Broadbent, Supervisor, Pisgah National Forest, August 6, 1935.

31. Telephone interview with Roger Miller, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Gatlinburg, Tenn., November 15, 1979.

32. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 125.

33. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 12.

34. W.O. Whittle, "Movement of Population From the Smoky Mountains Area," University of Tennessee Agricultural Experiment Station, 1934, p. 2.

35. Jerome Eric Dobson, "The Changing Control of Economic Activity in the Gatlinburg, Tennessee Area, 1930-1973" (Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Tennessee, 1975), p. 13.

36. W.O. Whittle, "Movement of Population From the Smoky Mountains Area."

37. Telephone interviews with Roger Miller, Gatlinburg, Tenn., November 15, 1979, and February 18, 1982. The principal inholding is a 2,300-acre tract owned by Cities Service Corp., just north of Fontana Lake. The other very small scattered tracts are the park borders and may be deleted.

38. Jerome E. Dobson, "The Changing Control of Economic Activity," Ph.D. dissertation, p. 91.

39. Dobson, "The Changing Control," p. 91.

40. Interview with Frank Sharp, Forester, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, May 11, 1979.

41. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 131.

42. Campbell, Birth of a National Park, p. 130-132.

43. Rick Gray, "Swain County Gets Political Ear," Greensboro Daily News, August 20, 1978.

44. Rick Gray, "Swain County."

45. Harley E. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway: Origins and Early Development" (Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University, 1974), p. 71.

46. Harley E. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," p. 76.

47. The Asheville Citizen, June 28, 1934, in Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," p. 89.

48. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," p. 78.

49. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," p. 80.

50. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," Chapter 8.

51. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," p. 174.

52. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," p. 180.

53. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," p. 191-194.

54. NA, RG 83, FHA (USDA), Land Use Summary Reports for Project LP-VA-8, and LP-NC-11, Blue Ridge Parkway Project, Land Utilization Reports, Relocation of Families.

55. NA, RG 83, FHA, Land Use Summary Reports, Blue Ridge Parkway Project, FHA, p. 11.

56. NA, RG 83, FHA, Land Use Summary Reports, Blue Ridge Parkway, FHA, p. 14.

57. Jerome E. Dobson, "The Changing Control of Economic Activity," Ph.D. dissertation, p. 137.

58. Harley E. Jolley, "The Blue Ridge Parkway," p. 189.

59. Harry Caudill, Night Comes To The Cumberlands. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962, pp. 184-186.

60. See, for example, Jeffrey Wayne Neff, "A Geographic Analysis of the Characteristics and Development Trends of the Non-Metropolitan Tourist—Recreation Industry of Southern Appalachia" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tennessee, 1975); Dobson, "The Changing Control of Economic Activity;" and Anita Parlow, "The Land Development Rag," in Colonialism in Modern America: The Appalachian Case, pp. 177-198.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region8/history/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2008