|

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81 |

|

Chapter VI

World War II Through the Fifties: From FDR to JFK

World War II marked the beginning of major economic and demographic changes in the Southern Appalachians. The wartime boom was temporary, and afterward the Depression returned. Many people left to find work elsewhere; rural farm population declined dramatically between 1940 and 1960. Meanwhile, Federal land acquisition nearly stopped as national priorities shifted. The Forest Service had to cope with a major increase in demand for outdoor recreation and balance that demand with other forest uses and needs. Although problems of National Forest management in the Southern Appalachians during the 1950's occurred in apparent calm, the region's poverty remained, and the potential conflicts among forest uses which were to receive national attention in the 1960's had already appeared.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, new and increasing demands were placed on the Nation's manpower and natural resources, demands that accelerated when this country entered the war in December 1941. Wartime production and mobilization revitalized the Depression-worn national economy. By 1944 half the country was engaged in war-related production, and full employment had returned. [1] The Southern Appalachians experienced a good share of wartime changes as coal and timber prices began to rise. Old jobs in mining and lumbering reopened and new industries were established close to the mountains. Although emergency New Deal programs were gradually phased out, the popular and effective CCC lasted until war came to America, and the Tennessee Valley Authority continued to provide construction and related employment through the war years.

|

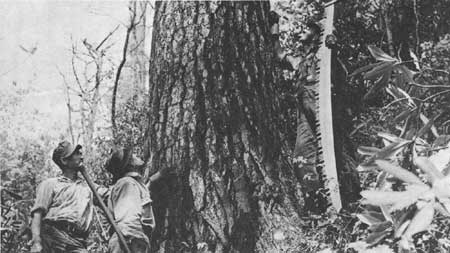

| Figure 77.—Crew with crosscut saw and double-bit axe checking large mature white pine marked for harvest for the Appalachian Forest Products mill near Clayton, Rabun County, Ga., on Chattahoochee National Forest, July 1941. The mill was the first to be operated on a sustained-yield basis in North Georgia and depended on the Forest for most of its timber. (Forest Service photo F-414090) |

Heavy Demand for Timber

Demands on the Nation's timber resource were heavy. Wood was needed to build bridges, barracks, ships, aircraft, and above all packing crates for shipping supplies overseas. Vital wood products were cellulose for explosives, wood plastic, rosin, and glycerol. Wood was classified as a critical material by the War Production Board. Although the heaviest demand for wood fell on the Douglas-fir forests of the West and the coastal southern yellow pines, the hardwoods and conifers of the southern mountains were also needed. [2]

The wartime demand for timber increased sales from National Forests throughout the South—from 94.2 billion board feet in 1939 to 245.3 billion in 1943. [3] High war demands led to heavy cutting, especially of such desirable hardwoods as redgum and yellow- (tulip) poplar. There was a strong market even for previously unwanted "limby old field pines and inferior hardwoods." The total cut was still less than half of the estimated overall timber growth there, however. This was true because the forests all contained considerable second-growth timber which, although growing rapidly, was still not mature enough for harvesting. [4]

|

| Figure 78.—Crew using peavies to roll a huge yellow-poplar log down to loading platform on Chattahoochee National Forest, July 1941. (Forest Service photo F-414105) |

Reflecting Forest Service policy, and the generally scattered and small volume available, about 90 percent of the timber was disposed of in sales of less than $500 each. The supervisor of the Cumberland (since renamed Daniel Boone) National Forest related in 1941:

. . . one mountain inhabitant purchased sufficient timber in small lots to make 1,200 railroad ties. He hired help to cut the timber; hewed the ties himself; skidded them to the roadside with his own mule; hired trucking of his product to the point of acceptance. He cleared about $600 on his operations. He has 14 children. This $600 was probably more money than the family had seen in the last eight years. [5]

Such sales were intended to take care of the little man, but they also made timber sale supervision and coordination harder. As the war went on, forest administration became more difficult. Many men had been drafted or had enlisted. Thus, timber stand improvement work, as well as cleanup and road repair work after timber sales, were not being done. [6] An assessment of the situation in Region 8 in 1943 stated that "in general, standards of performance are poorer," largely because "many of our best men are in the armed forces and have had to be replaced with poorer ones." [7]

Even a large outfit that had been logging in the region since 1900 felt the pinch. When the supervisor of the Chattahoochee National Forest asked the Gennett Lumber Co. in September 1944 why it had left logs in an area, an agent responded:

. . . we had not intended to abandon any scaled logs that are on Cynth Creek . . . we were forced to move over to Owl Creek so we could get men to operate. The labor situation got so critical on Cynth Creek that we could not keep things going. . . [8]

Since this forced the Forest Service to scale the area twice, a penalty was considered. The supervisor explained, "At a time when we are short of men and pushed to get the job done, the leaving of incompleted areas is costly to both you and us." [9]

As discussed earlier, land acquisition had been a major activity before the war. As late as 1937, it was felt that "the extension of government ownership in areas of low production and high watershed values as in the mountainous . . . sections [of Region 8] is unquestionably desirable." [10] However, Weeks Act funds dropped dramatically, from $3 million or more per year to $354,210 in 1943, $100,000 in 1944, $75,000 in 1945, and nothing at all in fiscal year 1946. [11]

However, land exchanges continued briskly through the war period. Desirable inholdings and adjacent lands were acquired in exchange for timber from Forest Service lands, with emphasis on facilitating sustained-yield management, experimental forests, and administrative economy. [12]

One problem, which was to become of increasing significance later, first appears in reports from war years. This was the decline in personal contact between National Forest officers, especially district rangers, and the people living on or near the forests. A 1943 forest inspection report observed that, because of the volume work, "they (the rangers) know the bankers, members of service clubs, etc., but the lesser lights living on the forest are neglected." [13] Rangers already had less of what oldtimers on the Cherokee refer to as "spit-and-whittle time." Mountain people prefer those who are not in a hurry to do business, but will "set a spell," and visit. [14] Fortunately, a reservoir of goodwill between the Forest Service and mountaineers had been build up during the Depression, chiefly through the CCC. Only after the war would a lessening of such personal contacts lead to friction.

|

| Figure 79.—Lumber crew rolling yellow-poplar logs from skidway platform to truck on Chattahoochee National Forest, July 1941. (Forest Service photo F-414107) |

Coal Mining Revived

In addition to demands for timber, the war brought huge orders for coal, giving the few mining companies that had survived the Depression a new lease on life. As demand grew, new companies were formed, and by 1942 it was boom time again in Southern Appalachian coal country. Miners returned to the delapidated company towns, and new housing was hastily constructed. Old men, youngsters below draft age, and those with serious health problems were accepted for mine work. The military had swept up the cream of mountain youth, fortunately for many of them. However, the development of heavy-duty trucks and the "duckbill" coal loader helped reduce the need for manpower, a trend that accelerated. [15]

Depression-born attempts to diversify the economy of the coal-producing regions were wiped out by the demand of the wartime boom. As Caudill describes it:

The whole attention of the area's population fastened again on coal. The blossoming farmers among whom County Agricultural Agents had worked so hard discarded seed sowers and lime spreaders for picks and shovels. The small but growing herds of pure-bred livestock were turned into pork and beef. [16]

The same could be said for efforts to develop the timber resources of the coal counties. Early in the war the last stands of "virgin" hardwood forest in Kentucky were cut. Only in the cutover lands purchased for the new Cumberland National Forest was any thought given to creating a sustained-yield forest that could provide a continued wood-using industry in the area.

The benefits of the wartime boom, however, should not be exaggerated. As L. E. Perry, a former general ranger district assistant and fire control officer for the Forest Service on the forest, has written of the impact of the wartime economy on McCreary County, Ky.:

The coal and lumber industry was vigorous in McCreary County but there was an exodus of the working people, even teachers, to northern plants and to the armed services. Consequently, there were shortages—of materials; manpower; money. Food and fuel were rationed. There was not enough of anything to go around. Hoarding and the blackmarket flourished . . . When at last the war was over, recovery was slow. [17]

In some areas of the Southern Appalachians, stepped-up coal and timber production continued for several years after the war. For example, in Clear Fork Valley of Claiborne County, Tenn., between the Cumberland and the Cherokee National Forests, 10 underground mines producing 750,000 tons of coal a year and employing nearly 1,400 men were still actively operating in 1950—a holdover from war production years. However, like other Southern Appalachian counties almost entirely dependent on one or two extractive industries, Claiborne succumbed to a serious postwar depression, keenly felt by the mid-1950's. [18]

Helping to hold up the postwar demand for soft coal in the eastern Kentucky and Tennessee area was a new steam power plant constructed there by the Tennessee Valley Authority. The Stearns Coal and Lumber Co. of Stearns, Ky., was alert to this new major consumer of its main product. Early in 1953 the company contacted the District Ranger at Stearns and the Supervisor of the Cumberland National Forest at Winchester. It was anxious to rework the coal seams in the 47,000 acres it had sold the Government more than 15 years earlier. Many of the old seams still contained blocks of coal close to the surface of hillsides. This coal had not been removed during earlier deep mining because of the danger of collapse of the mine tunnels. Now, with higher prices and recently developed earth-moving equipment, this coal could be recovered by strip-mining. The soil and rock cover could be dug away with power shovels and bulldozers to expose the coal for loading directly into huge trucks. The debris would be mostly dumped down the hillsides, thus clogging streams.

The Forest Supervisor, H.L. Borden, told Stearns that he was opposed to permitting strip-mining on the tract. A clause in the 1937 deed of sale for the Stearns tract reserved authority for the Forest Service to require adequate reclamation of ground surfaces disturbed by mining. Borden retired in May. He was succeeded by Robert F. Collins, who met with company officials in August and received a formal request a week later. Collins sent a copy of the request to the Eastern Regional Forester, Charles L. Tebbe, with a memo of his own urging that the request be denied. Collins pointed out that serious erosion and stream pollution would result, if approval were granted, and the action would thus be in direct violation of the stated purposes of the Weeks Act, which authorized the National Forest land purchases. In addition, he noted that a dangerous precedent would be set for National Forests throughout the East where mineral rights had been reserved. It was estimated by the Forest Service that 2,000 linear miles of strip-mining in the old Stearns tract could result from approval of the request.

The Stearns request was reviewed by the Regional Office in Philadelphia and by the Washington Office and lawyers of the Department of Agriculture. A consensus was reached, and on January 29, 1954, Tebbe officially denied the request.

On July 1, 1954, the company renewed its request, pointing out that a new Kentucky strip mine law requiring surface reclamation had just become effective, and contending that this law should provide adequate protection to the affected areas. (See Chapters VII and VIII). On July 30, Tebbe again denied the application. On August 29, Robert L. Stearns, Jr., president, appealed in person to the Secretary of Agriculture, Ezra Taft Benson, in Washington. Benson referred the request to Richard E. McArdle, Chief of the Forest Service, who again conferred with his staff and with Department lawyers. Convinced that such mining would irreparably damage the land, streams, and wildlife of the Forest, McArdle denied the appeal, which was then taken to the Secretary for a final decision.

McArdle suggested that a special board be appointed by Benson to study the situation and give an advisory, but not binding, opinion. The board would be composed of a noted leader in the national resource field, a professional mining engineer, and a public member to be chosen by the other two. Benson and Stearns agreed. The men appointed were Samuel T. Dana, who had just retired as chairman of the Department of Natural Resources at the University of Michigan; Robert L. Wilhelm, a coal operator of St. Clairsville, Ohio; and Charles P. Taft, a prominent Cincinnati attorney who was son of former President William H. Taft and brother of the Republican Senator, Robert A. Taft. The board visited the area in January 1955 and examined the sites that would be strip-mined as well as other sites being strip-mined. The board also conducted a public hearing near Stearns, which attracted wide publicity. During the entire period of this controversy the Forest Service had received many letters from the public, mostly opposing the mining project.

On May 12, 1955, the board reported to Benson that a majority recommended denial of the Stearns request. On July 22, 1955, Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Ervin L. Peterson publicly affirmed the Forest Service denial. The company decided not to appeal the decision in the courts. [19]

During the war the labor-short lumber and mining industries had tried hard, with varying success, to gain draft deferments for their skilled employees. The Gennett Oak flooring Co. of North Carolina pleaded with the Asheville draft board to let it retain experienced workers to meet demands of the War Production Board for lumber and avert a shutdown. [20]

Wartime military service changed the outlook and lives of many. Young men often did not return permanently to the mountains. The "G.I. Bill of Rights" offered college education to those who might never have considered it. With new skills and confidence gained during military service, they worked to become teachers, engineers, pharmacists, doctors, lawyers, and football and basketball coaches. A few even studied forestry, a subject they had first come to know as teenagers in the CCC. [21]

|

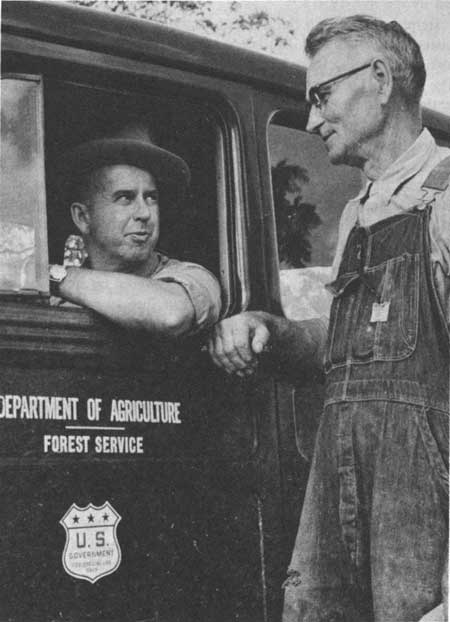

| Figure 80. Ranger Edgar F. Wolcott, Wythe District, Jefferson National Forest, Va., talking with a local farmer in July 1958. (Forest Service photo F-487235) |

The Tennessee Valley Authority

One New Deal program which continued to flourish during the war was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Increasing needs for electric power, especially for aluminum production, quieted the opposition of industry to increased TVA power-generating capacity. In 1942 and 1943, TVA had 42,000 employees working on 12 projects throughout the Southern Appalachian region, the highest employment figure ever recorded by the agency. [22]

Most impressive of all was Fontana Dam on the Little Tennessee River high in the mountains of Swain and Graham Counties, N.C., just south of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Fontana, the highest dam east of the Rockies, built to generate electric power for industry, was claimed to be justified by the war effort; it was rushed with a sense of urgency and high purpose. Before work could begin a road had to be built to carry in heavy construction equipment. Fontana Village, with peak population of 6,000, was built nearby for workers and their families. Work on the dam began shortly after Pearl Harbor, and for nearly 3 years men worked in round-the-clock shifts, under floodlights at night. In November 1944 the dam was finally closed and Fontana Lake began to fill, only a few months before the end of the war. [23]

Jobs were plentiful everywhere during those years; therefore to keep workers at Fontana, a model community was developed, with library, schools, a small hospital, and recreational facilities. The project manager encouraged planting of gardens and flowers as an excellent way to reduce turnover in the work force. Those who planted gardens would want to stay and see them grow. [24]

Besides hydroelectric power, TVA plants produced fertilizers, chemicals for munitions, and synthetic rubber. The cartographic section of TVA, established to design maps of the region as an aid in planning and land purchases, was used by the Army to make maps for military planning. Supplying wartime needs helped TVA maintain political independence and continue many of its long-range social goals.

The uranium processing facilities for the atomic bomb, at Oak Ridge, Tenn., just west of Knoxville in Anderson County, require brief mention. The most notable aspect of the project that mattered to the local population was that they were forced permanently out of their ancestral homes and their community was destroyed. Today many East Tennesseeans take pride in the scientific accomplishments of Oak Ridge; however, in 1941, their parents' and grandparents' prime concern was that the Army Corps of Engineers suddenly swooped in to condemn 59,000 acres of land, and abruptly evicted nearly 1,000 bewildered and resentful rural families from their homes and farms. No argument or protest was permitted; the need was considered too urgent.

Operating under the cover name of Manhattan Engineering District, Marshall (chief of the district) and his colleagues moved quickly—too quickly for many of the people in this affected area of Tennessee. After a September site inspection by Brig. Gen. Leslie R. Groves, named in this month to head the entire Manhattan Project, a battery of Corps attorneys and surveyors entered the area and began mapping. In early October, condemnation proceedings got under way and a declaration of taking was filed in federal court at Knoxville. It called for immediate possession of the land, even though appraisals and transactions with individual owners had not yet begun.

By November, residents leaving the area were passing an incoming flood of construction workers. [25]

Partially because of the population dislocation and partially because of the influx of atomic energy employees from other regions, the Knoxville area swelled in population during the 1940's. When the Oak Ridge plants were phased down during the 1950's, Knoxville experienced a net migration loss. [26]

In sum, the wartime emergency brought a temporarily booming economy to the Southern Appalachians. The natural resources of the region—timber, coal, and water power in particular—were in high demand; the labor supply to marshall the resources was short. Prices and wages were high, as the area responded to wartime needs. With an emphasis on military materiel production, certain aspects of prewar forest management, such as land acquisition (except for Oak Ridge), recreation, and conservation, were momentarily de-emphasized. These concerns, however, returned to importance when the war mobilization wound down.

|

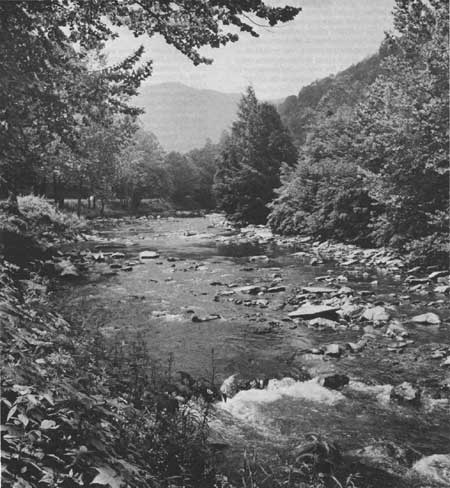

| Figure 81.—Nantahala River in the Gorge above junction with Little Tennessee River and Fontana Lake, a Tennessee Valley Authority power and flood control reservoir on the border of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Swain County, N.C., in July 1960. Nantahala National Forest. (Forest Service photo F-494664). |

Heavy Migration to Cities

The Second World War not only affected national production and employment levels, it also brought large-scale shifts in population distribution. Between 1940 and 1950 about 1 million people migrated from farms to cities, and stayed there. The national rural-to-urban migration accelerated during the 1950's, as more than 5 million persons from nonmetropolitan areas moved to Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas (SMSA's). The Southern Appalachian region contributed many migrants to other regions during and after the war, as its farm population declined sharply, and manufacturing became increasingly important.

Population changes in the Southern Appalachians between 1940 and 1960 were particularly dramatic. Between 1940 and 1950, its rate of growth fell below 10 percent for the first time since the first census of 1790. Between 1950 and 1960, its population declined. [27] Over the 189-country area defined by the 1960 Thomas Ford study, this loss was 2.8 percent, or about 160,000 persons. Net migration loss alone (in vs. out) was 19 percent. [28] However, the change and the rate of change in population growth varied considerably. The Valley and Ridge subregion on the east side gained population, through urban-industrial growth in the broad river valleys. But the Appalachian Plateau subregion, particularly eastern Kentucky, had heavy losses, due primarily to the sharp postwar drop in coal industry employment as new technologies, and greater use of alternative fuels such as oil and gas, forced economies in the coal market. The population of the Blue Ridge subregion did not change markedly over the same period. Here, "the development of industry and tourism undoubtedly served to retard out-migration." [29]

As with the Nation as a whole, metropolitan areas of the Southern Appalachians grew more or lost population less between 1940 and 1960 than did the nonmetropolitan areas. Between 1940 and 1950, the nonmetropolitan counties gained by less than 15 percent, compared to 20 percent for the others. Between 1950 and 1960, nonmetropolitan population declined 6 percent; metropolitan population increased 7 percent. [30] The region's metropolitan gains over the two decades were minor compared to those in most such areas of the United States. In fact, between 1950 and 1960, all SMSA's of the region defined by Ford except Roanoke, although gaining population overall, experienced a net migration loss. Asheville and Knoxville lost migrants at relatively high rates. [31]

Most of the region's migration during the postwar years was between adjacent counties or within the same State. Available data on destinations of migrants into and out of the region during 1940-50 show most movement was short, intracounty or to a contiguous county. In more than 80 percent of the region, less than 20 percent of the migrants went to another State. Of those who did, the patterns were fairly regular over the two decades. Most interstate migrants from the Appalachian Plateau subregion moved to Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois. Most migrants from southwestern Virginia, if they left the state, traveled to the District of Columbia and Maryland, [32] where Federal employment offered opportunities.

In general, as with most migrations, the majority were young—between 18 and 34. Most were white, male, and above average in education. Outmigrants, especially those moving longer distances, tended to be younger than inmigrants. Thus, in the postwar period, the population of the Southern Appalachian region defined by Ford became relatively older, with more persons 65 or over. Also, because women of child bearing age were leaving in increasing numbers, a slowing down of the region's rate of natural increase for the following decades was assured. [33]

The demographic shifts that occurred in the region during and after the war are reflected in farm statistics. Between 1940 and 1950, its rural farm population declined sharply, so that in 1950, for the first time, the rural farm population was smaller than either the rural nonfarm or urban populations. [34] During the 1940's, as many who had held onto their farms during the 1930's found employment elsewhere, the rural farm population experienced a net loss due to migration of 595,000 persons, a rate of over 28 percent. This loss was greatest in the Kentucky counties, followed by those of Tennessee. [35]

Demographic Changes Are Confirmed

For the smaller area of the Southern Appalachians on which this study focuses, the demographic changes between 1940 and 1960 were very nearly as dramatic as for the larger region defined in Ford's study. In both decades the coal counties of eastern Kentucky had the greatest outmigration losses and the greatest population shifts. Within the area with a high concentration of land in National Forests, most counties experienced a net migration loss. The greatest migration losses (40 percent or more) from 1940 to 1950 were in Kentucky: the Cumberland National Forest counties of Jackson and Wolfe; as well as in Hancock County, Tenn., a coal county, and Swain County, N.C., most of which is within the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Other counties suffering heavy net outmigration were Polk County, Tenn., and Rabun County, Ga., both of which had a large proportion of land in National Forest; and the Kentucky counties of Estill, Lee, Morgan, Menifee, Harlan, Letcher, Perry, and Clay. [36] Between 1950 and 1960, the greatest losses from net out-migration were experienced in Lee County, Va.; Swain County, N.C.; and the eastern Kentucky counties of McCreary, Bell, Harlan, Letcher, Perry, and Leslie. [37]

In general, then, the heaviest net outmigration from the Southern Appalachians during the period from 1940 to 1960 was from coal-producing counties. That is, population loss appears chiefly correlated with changes in the mining industry, not with changes in Federal land acquisition or land policy. One exception stands out: Swain County, N.C. The heavy move from Swain County was forced by the closing of Great Smoky Mountains National Park to residents. Between 1940 and 1950, over 40 percent of them left, many to adjacent Sevier County, Tenn., where Gatlinburg is located. Sevier was one of the few counties to show a net migration gain. [38]

12 Counties Are Selected For Full Analysis

For a narrower focus on the demographic and economic changes that have occurred in the Southern Appalachians since World War II, we have selected a group of 12 mountain counties for further detailed analysis. This group consists of six counties with a high proportion of land in National Forests and six counties with little or no National Forest land. The former counties are considered representative of the core counties of the region. Each has a long (at least 40-year) history of Federal land acquisition and land management.

The latter group was selected as approximating many of the physical traits of the former group except for high Federal landownership. Each is mountainous (although not so much as the counties of the former group) and nonmetropolitan. Each is adjacent to or near the counties with a high proportion of National Forest. At least one county of each type was selected from all the five States of the study area. However, two of each type were selected from North Carolina, because of the presence of two National Forests there. The 12 counties are listed in table 4.

Table 4.—Twelve Southern Appalachian counties selected for comparison and detailed analysis: percentage of land in National Forests

| County and State | National Forest | Percentage of land in National Forest 1980-1981 |

| High proportion of National Forest | ||

| Union County, Ga. | Chattahoochee | 48 |

| Graham County, N.C. | Nantahala | 58 |

| Macon County, N.C. | Nantahala | 60 |

| Unicoi County, Tenn. | Cherokee | 46 |

| McCreary County, Ky. | Daniel Boone (Cumberland) | 45 |

| Bland County, Va. | Jefferson | 30 |

| Little or no National Forest | ||

| Habersham County, Ga. | Chattahoochee | 22 |

| Ashe County, N.C. | Pisgah | under 1 |

| Henderson County, N.C. | Pisgah | 7 |

| Hancock County, Tenn. | None | None |

| Knox County, Ky. | Daniel Boone (Cumberland) | under 1 |

| Buchanan County, Va. | None | None |

Source: Lands Staff, Southern Region, Forest Service, USDA, Atlanta, Ga.

The population changes that occurred in the 12 study counties from the period 1940 to 1960 are representative of those that occurred across the greater Southern Appalachian region. These changes are shown in table 5. All 12 counties experienced net migration losses for both decades; however, from 1950 to 1960 the rate of natural increase was generally not great enough to offset the migration loss, and most counties experienced an absolute loss of population. [39] All six counties with a high proportion of National Forest land suffered population losses during the decade 1950-60; whereas, only three of the counties with little or no National Forest did. And, in the latter counties that did experience population declines—Knox, Ashe, and Hancock—the losses were generally more severe than those experienced by the counties with a high percentage of National Forest land.

Table 5.—Population changes in 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties, 1940-60

| County and State | Percentage change in total population |

Percentage change in net migration | ||

| 1940-50 | 1950-60 | 1940-50 | 1950-60 | |

| High proportion of National Forest | ||||

| Union County, Ga. | -5.0 | -11.0 | -23.5 | -25.0 |

| Graham County, N.C. | +7.0 | -6.6 | -13.4 | -25.0 |

| Macon County, N.C. | +2.0 | -7.7 | -14.0 | -22.0 |

| Unicoi County, Tenn. | +12.0 | -5.0 | -2.5 | -22.0 |

| McCreary County, Ky. | +1.0 | -25.0 | -15.0 | -43.0 |

| Bland County, Va. | -4.4 | -7.0 | -15.6 | -19.0 |

| Little or no National Forest | ||||

| Habersham County, Ga. | +12.0 | +9.0 | -3.9 | -8.0 |

| Ashe County, N.C. | -3.5 | -10.0 | -18.2 | -25.0 |

| Henderson County, N.C. | +19.0 | +17.0 | -14.1 | +2.8 |

| Hancock County, Tenn. | -19.0 | -15.0 | -30.7 | -30.0 |

| Knox County, Ky. | -2.0 | -17.0 | -18.6 | -32.0 |

| Buchanan County, Va. | +13.6 | +2.7 | -10.3 | -24.0 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, County and City Data Book (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1947, 1952, 1962).

The population losses in the study counties between 1950 and 1960 can only marginally be attributed to an increase in National Forest acreage. Most of the counties in question gained no more than 4 percent in National Forest land ownership over the decade, but experienced more than a 20-percent net migration loss. As with the Southern Appalachian region as a whole, the counties of eastern Kentucky—McCreary and Knox—suffered the most severe population declines.

The population changes experienced by the 12 study counties between 1940 and 1960 are reflected strikingly in farm statistics for those years, as shown in table 6. For the six counties with a high percentage of National Forest land, the number of farms declined over the two decades by a weighted average of 45 percent. For the six non-National Forest counties, the average decline was 43 percent. That is, the decline in the number of farms does not appear to be related to Federal land-ownership. The counties that experienced the greatest decrease in number of farms over the period 1940 to 1960 were McCreary, (68 percent decline), Knox (63 percent), and Buchanan (57 percent), all predominantly coal counties in the Appalachian Plateau. This pattern confirms the finding of the Ford study over the whole Southern Appalachian region that from 1940 to 1960 the Cumberland coal counties lost the greatest farm population through migration.

Table 6.—Number of farms and total farm acreage in 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties, 1940-59

| High proportion of National Forest |

Little or no National Forest | |||||||||||

| Year | Union, Ga. | Graham, N.C. | Macon, N.C. | Unicoi, Tenn. | McCreary, Ky. | Bland, Va. | Habersham, Ga. | Ashe, N.C. | Henderson, N.C. | Hancock, Tenn. | Knox, Ky. | Buchanan, Va. |

| Number of farms | ||||||||||||

| 1940 | 1325 | 818 | 2243 | 1100 | 1675 | 918 | 1386 | 4153 | 2323 | 1768 | 3432 | 2420 |

| 1950 | 1303 | 759 | 2276 | 926 | 1162 | 787 | 1413 | 3886 | 2394 | 1820 | 2763 | 2341 |

| 1959 | 861 | 587 | 1203 | 741 | 540 | 552 | 728 | 3040 | 1368 | 1466 | 1274 | 1029 |

| Pct. change 1940-59 | -36 | -28 | -46 | -33 | -68 | -40 | -47 | -27 | -40 | -17 | -63 | -57 |

| Farm Acreage (thousand acres) | ||||||||||||

| 1945 | 87 | 40 | 136 | 41 | 50 | 101 | 247 | 135 | 120 | 159 | 163 | |

| 1959 | 74 | 30 | 87 | 35 | 57 | 111 | 65 | 220 | 97 | 114 | 80 | 71 |

| Pct. change 1945-59 | -15 | -25 | -36 | -15 | +14 | -52 | -36 | -11 | -28 | -5 | -50 | -56 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, County and City Data Book (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1947, 1949, 1952, 1962).

Throughout the southeastern mountains, farm acreage also declined markedly during and after the war. Again, no clear differences were evident between the counties with a high proportion of National Forest land and those with little or none. In fact, of the study group of 12, the two counties that experienced the heaviest declines in farm acreage from 1945 to 1959 were Knox (50 percent) and Buchanan (56 percent), neither of which contained any National Forest acreage.

Because migration destination questions were not asked on the 1940, 1950, or 1960 Censuses, it is not possible to know where the lost farm population of the 12 southeastern mountain counties relocated. It is likely, however, that the farm migrants followed the pattern exhibited throughout the region: most settled in urbanizing areas close by—in either the same or an adjacent county—and if not, probably within the same State.

The shift in farm acreage and farm employment is also reflected in statistics on the growth of the number of manufacturing establishments and of manufacturing employment in the study counties, as shown in the table in table 7. Between 1939 and 1947/1948, the number of manufacturing establishments in the heavily national forested counties swelled. This growth, which ranged from 55 percent in Unicoi County to 1300 percent in Union County, was probably a response to wartime demands on their timber resources. Growth in the number of manufacturing establishments in the non-National-Forest counties for the same time period was not quite so pronounced. However, this latter group had more manufacturing establishments to begin with.

Table 7.—Changes in number of manufacturing establishments and employees in 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties 1939-58

| High proportion of National Forest |

Little or no National Forest | |||||||||||

| Year | Union, Ga. | Graham, N.C. | Macon, N.C. | Unicoi, Tenn. | McCreary, Ky. | Bland, Va. | Habersham, Ga. | Ashe, N.C. | Henderson, N.C. | Hancock, Tenn. | Knox, Ky. | Buchanan, Va. |

| Number of manufacturing establishments | ||||||||||||

| 1939 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 14 | 0 | 7 | 5 |

| 1947 | 13 | 2 | 18 | 14 | 18 | 12 | 41 | 26 | 37 | 2 | 12 | 13 |

| 1954 | 17 | 9 | 26 | 17 | 13 | 12 | 57 | 34 | 49 | 7 | 12 | 26 |

| 1958 | 10 | 7 | 33 | 16 | 14 | 25 | 51 | 46 | 58 | 4 | 21 | 31 |

| Number of employees in manufacturing | ||||||||||||

| 1939 | D1 | D | 77 | 537 | 249 | 273 | 551 | 737 | 1380 | 0 | 154 | 53 |

| 1947 | 44 | D | 351 | 1378 | 375 | 206 | 1749 | 173 | 1739 | D | 357 | 299 |

| 1954 | 76 | 237 | 369 | 1000 | 159 | 235 | 2087 | 540 | 2348 | 27 | 176 | 199 |

| 1958 | 42 | 270 | 762 | 482 | 59 | 328 | 2288 | 1028 | 3322 | 18 | 320 | 192 |

1D = Disclosure laws prohibit publication for one or two firma only.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, County and City Data Book (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1947. 1949, 1952, 1956, 1962).

In general, for both sets of counties, manufacturing continued to expand throughout the 1950's, although in some counties growth slowed after the wartime spurt. For most counties, the majority of the manufacturing units were small, employing fewer than 20 persons. Henderson County had the highest percentage of large establishments (in 1954, 43 percent had 20 or more employees and 10 percent had 100 or more). On the other hand, several counties in both groups—Union, McCreary, Hancock, and Buchanan—had only small manufacturers in 1958, with fewer than 20 employees.

In terms of total number of employees, the war brought a substantial marshalling of labor into industry. In both sets of counties the number of manufacturing employees approximately doubled between 1939 and 1947. As with the number of plants, this growth was not always sustained through the 1950's. By 1958, Union, McCreary, and Unicoi Counties had fewer employees in manufacturing than they had had during wartime. The pattern of sustained growth was more clearly evident in the counties with little or no National Forests; all but Hancock and Buchanan Counties continued to grow in manufacturing employment throughout the postwar decade.

During the 1940's and 1950's, retail establishments did not contribute to the economic well-being of the Southern Appalachians as clearly as manufacturing did. In all 12 study counties except 3, the number of retail units actually declined between 1939 and 1958, as table 8 reveals. The decline appears to have been most severe between 1948 and 1954. These years probably represent the peak period of postwar economic stagnation in the Southern Appalachians, when the war's end most severely affected the region's agricultural and industrial base, and outmigration swelled. Two decades of public relief measures, private development, and local initiative were needed to reverse the depression conditions and slow evacuation of the Southern Highlands.

Table 8.—Number of retail establishments in 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties, 1939-58

| High proportion of National Forest |

Little or no National Forest | |||||||||||

| Year | Union, Ga. | Graham, N.C. | Macon, N.C. | Unicoi, Tenn. | McCreary, Ky. | Bland, Va. | Habersham, Ga. | Ashe, N.C. | Henderson, N.C. | Hancock, Tenn. | Knox, Ky. | Buchanan, Va. |

| Number of units | ||||||||||||

| 1939 | 68 | 46 | 149 | 153 | 168 | 58 | 171 | 229 | 266 | 87 | 266 | 364 |

| 1948 | 88 | 54 | 149 | 163 | 160 | 60 | 221 | 237 | 348 | 83 | 259 | 305 |

| 1954 | 48 | 38 | 154 | 126 | 104 | 40 | 164 | 130 | 356 | 41 | 194 | 284 |

| 1958 | 44 | 36 | 167 | 143 | 103 | 42 | 194 | 174 | 345 | 42 | 227 | 293 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, County and City Data Book (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1947, 1949, 1952, 1956, 1962).

|

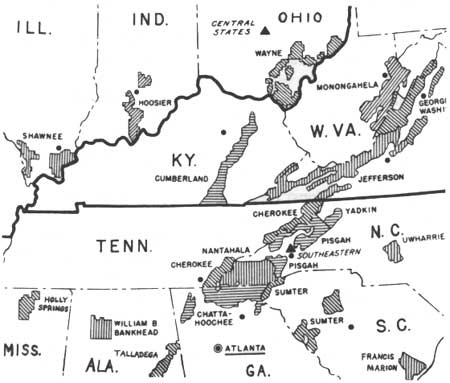

| Figure 82.—The National Forests and Purchase Units, and the National Parks of the Southern Appalachian Mountains in 1948. Only changes from 1940 are the name of the Black Warrior National Forest in Alabama (not in the mountains) to William B. Bankhead, the spelling of Uharie to Uwharrie in North Carolina, and a new unit added to the Chattahoochee National Forest in Georgia. (Forest Service map and photo) |

Land Exchanges Replace Purchases

Land acquisition for the National Forests virtually ceased during the war. There were no regular meetings of the National Forest Reservation Commission, although "recess approval" was given for several purchases on which work had begun before the war.

On February 7, 1947, the NFRC held its first postwar meeting. Congress appropriated $3,000,000 for forest purchases in 1947, and the prewar program of acquisition in existing purchase units was renewed. However, appropriations for land purchase steadily declined during the remaining years of the Truman administration. In 1948, appropriations were only $750,000; by 1951, they dropped to $300,000. [40] The Commission did not resume the close supervision of land acquisition and the policymaking functions it had often assumed before the Second World War. Purchases were routinely approved by recess action and, when actual meetings were held, Cabinet members and other important figures were represented by deputies rather than attending in person, as had been customary before the war. The most important land purchase program was in the Superior National Forest of Minnesota for the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. [41]

Because funds were so limited and other regions had priority on forest purchases, land and timber exchanges played an increasingly important role in the consolidation of the Southern Appalachian National Forests and in efforts to add to the existing purchase units in the region.

Just after World War II many exchanges involved surplus military land. In 1949 the Forest Service gave 278 acres in the Chattahoochee National Forest, on which Camp Toccoa had been constructed during the war, to the War Assets Administration in exchange for 654 acres of surplus military land under its jurisdiction. The War Assets Administration later sold Camp Toccoa to the State of Georgia for conversion to a mental hospital. [42]

The Forest Service also obtained some postwar National Forest acreage through the Surplus Property Act of 1944.[43] Lands that had been acquired through bankruptcy or condemnation proceedings by the Federal Farm Mortgage Corp. could be purchased by the Forest Service. These lands were often bankrupt farms, abandoned and unproductive, or acreage owned by a bankrupt corporation. For example, in 1947 the Forest Service acquired 1,830.62 acres in the Jefferson National Forest that had been acquired by the Federal Farm Mortgage Corp. in condemnation proceedings against the bankrupt Triton Chemical Co. of Botetourt County, Va. The Forest Service paid $8,200.37, or about $4.50 per acre, for the tract. [44]

In efforts to substitute exchanges for the almost nonexistant land purchase funds, the Forest Service worked out some complicated tripartite exchanges involving land and timber. One such deal involved 7,603.7 acres of land belonging to the Vestal Lumber and Manufacturing Co. in Greene, Washington, and Unicoi Counties, Tenn., within the Cherokee National Forest. The land, which was cutover and contained only some poor, second-growth timber, was exchanged for an equal value of National Forest timber. However, the Vestal Co. itself was not going to cut the timber; it would simply receive payment from third parties who contracted for the timber. The exchange was delayed and threatened because Vestal wanted funds from the timber sales by a specified date. This the Forest Service could not promise, but the exchange was finally consummated in September 1956. [45]

In some cases, lands were purchased for the purpose of exchanging them for desired Forest Service acreage. For example, in 1953 the State of Georgia bought 239.15 acres of land in Union and Towns Counties. The land was described as "isolated, inaccessible, and of no known value to the state," but the State knew that it lay within the boundaries of the Chattahoochee National Forest and that the Forest Service wanted to acquire it. In 1956 Georgia exchanged this land for 105.10 acres in White County, which made possible the expansion of the White County Area State Park. [46]

On rare occasions during this time, the Forest Service received land donations, generally small, of 50 or fewer acres. In 1948, Mrs. Cornelia Vanderbilt Cecil, daughter of George Vanderbilt, who lived in London, England, donated 2.6 acres within the Pisgah National Forest to the Forest Service. The Lincoln Investment Corp. donated two tracts totaling 47.2 acres in Smythe County, Va., valued at $127.45. [47] One donation in the Jefferson National Forest reflected strong concern of local residents for conservation and ecology. The Virginia Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries planned to build a 65-acre lake in the Corder Bottom Area of the Clinch Ranger District. Only 50 acres of the lake were within the National Forest; 15 were in private ownership. The local Izaak Walton League chapter and the Norton Chamber of Commerce purchased the 15 acres, as well as a protective strip and mineral rights. These they donated to the Forest Service in September 1956, and thus assured that access to the lake would be entirely within the National Forest boundaries. [48]

Whether lands were purchased, exchanged, or even donated, the problem of extensive delays in the acquisition process continued. One striking example was in the Cumberland National Forest around 1950. After some negotiation, a widow, Mrs. Eva Kidd, agreed to sell 226.7 acres in McCreary County, Ky. She did not have clear title, so the land was acquired through condemnation proceedings. The Forest Service deposited payment, $680.70, with the court for disbursement, but for some reason Mrs. Kidd was not paid. Three years later, frustrated and annoyed, she visited the district ranger "once and sometimes twice a week insisting on settlement." The Forest Supervisor wrote to ask the U.S. Attorney in Lexington to make sure Mrs. Kidd got her money. Finally, in September 1953, a check was mailed to her, but sadly, she had died on September 7 so the check was returned. [49]

Another example of the frustrations involved in the land acquisition and exchange process is the case of Dr. Bernhard Edward Fernow, one of four sons of Bernhard Eduard Fernow, Chief of the Division of Forestry in the U.S. Department of Agriculture before Gifford Pinchot. Dr. Fernow, a mechanical engineer, purchased a summer cabin near Highlands, Macon County, N.C., in 1948. Slightly under an acre of the tract on which the cabin was situated encroached on Nantahala National Forest land; Fernow was asked to continue payment of $25 per year for a special-use permit to occupy the land.

A year later Fernow wished to purchase the acre. His request was denied by the Regional Forester, because Federal law forbade it. However exchange of land of equal value was permitted. So, Fernow then initiated requests to exchange other acreage for the desired 1 acre at his cabin site, but had considerable difficulty locating suitable land to exchange. The Forest Service valued the acre in question at $1,500 (the cost of a typical vacation site in the Highlands area in the early 1950's). Fernow, on the other hand, referred to the tract as no more than an "acre of rock."

After years of correspondence, negotiation, and finally the intercession of a South Carolina congressman and the Chief of the Forest Service, the matter was settled in 1957, 8 years after Fernow's original request for exchange. Dr. Fernow exchanged several tracts he had purchased in neighboring Jackson County, N.C., totaling 112.8 acres, for the 0.9 acre he desired for his summer cabin. [50]

After the election of Dwight D. Eisenhower as President in 1952, the Forest Service was uncertain what changes would accompany the end of 20 years of Democratic administration. The new (Republican) National Forest Reservation Commission met for the first time on June 17, 1954. Assistant Secretary of Agriculture J. Earl Coke explained that, "the department recommended to Congress that additional money for purchases under the Weeks Law not be provided, but Congress included some funds for this purpose so that the program will continue." [51] Some land funds were available through other programs, but Weeks Act purchases were limited to $75,000 for fiscal year 1954, the lowest since 1945. The major emphasis was on acquisition of Indian lands for the Chippewa National Forest in Minnesota.

The NFRC did not meet again until April 1956, though some purchases were approved by recess action in the interim. [52] Major actions were taken at the 1956 meeting. Eight purchase units were abolished and the boundaries of a number of others were changed. In general, the changes made the units smaller, though there were some exceptions. Land in Madison and Haywood counties, N.C., was eliminated from the Pisgah National Forest Purchase Unit. The Chattahoochee National Forest lost prospective additions to territory in Dade, Walker, Catoosa, Fannin, White, Banks, and Stephens Counties. A small addition was made in Habersham County to provide for better road access. Although tracts of land might still be acquired for consolidation, no real expansion of the units in the mountain forests was anticipated. Ironically, the recreation value of lands within or adjacent to the National Forests was now so high that the Forest Service could rarely afford to purchase such tracts. By improving its own lands, the Forest Service had enhanced the value of its neighbors' lands as well.

Thus, in the 15-year period that followed World War II, the impact of Federal land acquisition on the people of the Southern Appalachians was considerably less than it had been before the war. However adjacent landowners benefited from rapidly rising land values.

The number of Federal land purchases was far smaller than it had been during the New Deal, and exchanges were more likely to involve a land or lumber company, or a State or local government, than an individual. Further, the exchange program was slow and cumbersome. Nevertheless, the 1959 regional report recommended more use of "land for timber and tripartite procedures for acquisition of key holdings." [53] These exchanges could be maddeningly difficult to set up, but they became the best way of adding land to improve forest administration.

Local attention to Federal land agencies during the postwar decades more often focused on the Tennessee Valley Authority, which became increasingly visible and controversial during the Eisenhower presidency than it previously had been. Republicans generally did not favor public electric power development, and charges were made that industries had been "lured" to the Tennessee Valley by cheap subsidized power. Such charges were never substantiated, but TVA remained on the defensive. [54]

In addition, TVA's practice of transferring its lands to other governmental agencies drew attention to the condemnations of the 1930's and early 1940's. The Supreme Court had decided in 1946 that such transfer did not mean that TVA had illegally condemned unnecessary land. But large land transfers or sales still raised questions in local people's minds about the necessity for some of the earlier condemnations. [55] Most of the TVA transfers involved land originally acquired for TVA forests or for recreational development. However, because there had been some success in encouraging private landowners to carry out reforestation, original plans for TVA forests had been abandoned, except for one experimental tract. TVA policy favored leaving recreation development to other agencies or to local or private enterprise. Several large reservoir lakeside areas were sold or turned over to other governmental agencies for recreation use. For example, between 1947 and 1951, TVA relinquished nearly 11,000 acres of land south of Fontana Dam to the Nantahala National Forest. [56]

|

| Figure 83.—The National Forests and Purchase Units of the Southern Appalachian Mountains in 1958-59. The Purchase Units in Ohio and Indiana had become the Wayne and Hoosier National Forests, respectively. The areas of the Chattahoochee and Pisgah forests were reduced. Yadkin and Uwharrie in North Carolina were still Purchase Units. Black triangles are Forest Experiment Station headquarters of the Forest Service. Black dots are National Forest headquarters. Atlanta is regional headquarters. (Forest Service map and photo) |

Outdoor Recreation Use Skyrockets

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, many Federal agencies had begun comprehensive studies to plan projects to provide work that would ease the expected strains on labor and the economy in the shift from military to civilian production. Great effort and time were expended in making detailed long-range plans. The Forest Service was much involved in this work. It was recognized that a tremendous backlog of maintenance and improvement had built up during the war, particularly for recreation. It was considered urgent to reverse destructive logging which the war had encouraged. [57] Little came of these plans as the economy took care of itself, and the Forest Service gave up trying to regulate logging on non-Federal lands. It was also a decade before funds were again available to deal adequately with public recreation demands. In the Southern Appalachian forests, campgrounds and picnic areas built by the CCC, some of them already 10 or more years old, received increasingly heavy use after the end of the war. Families used accumulated savings to buy cars as soon as they became available. Gasoline was no longer rationed. More and more people took vacation trips into the mountains. Forest Service recreation development plans, shelved in 1941, were brought out again.

Even before World War II, recreational use of the National Forests had increased steadily. Between 1925 and 1940, visits to National Forests for recreational purposes rose from 5.6 million to 16 million. [58]

After World War II, recreational visits increased far more dramatically, as the graph in figure 84 reveals.

Thus, for National Forests as a whole, recreational visits increased by 400 percent (five times) between 1945 and 1956, and by over 900 percent (10 times) between 1945 and 1960. Much of this increase was in National Forests of the West. Region 8 had only a 188-percent increase in recreational use between 1945 and 1956 (less than threefold). However, within the Southern Appalachians such use increased much faster; in North Carolina it rose 333 percent (more than four times). [59]

With the end of the World War II, the recreational potential of National Forest lands was recognized by resort developers and promoters as well as those within the Forest Service. The issues involved in resort development in or near the National Forests can be seen in connection with one proposed development on a peninsula in Lake Santeetlah in Graham County, N.C., in the Nantahala National Forest. The developer, a Miami realtor, wished to exchange over 2,000 acres of forest land in the county adjacent to the National Forest for this 136-acre tract. He intended to build a 25-room resort hotel. Because the case was potentially precedent-setting, it drew the attention of the Acting Chief of the Forest Service, who discussed some of the problems in a memo to the Regional Forester.

First, he explained that the Forest Service "has gone to considerable effort and expense to acquire control of shore lines on lakes having substantial recreational values," to insure that development was "appropriate."

Another consideration is that this apparently contemplates the installation of a high-priced and rather exclusive resort. By reference to the policy statement under the heading of Purpose on page NF G-3(6) of the recreation section of the National Forest Manual, you will note that such installations require special justification. Our general policy is to favor more modest types, catering to persons of moderate means. [60]

On the other hand, the memo pointed out, "the opportunity to acquire a substantial area of forest land in the trade is not lightly to be dismissed." [61]

The decision was left to the Regional Forester. In order to gauge the value of the peninsula, he considered opening the land to vacation cottages. The Forest Service had been leasing sites for vacation homes since the 1920's. At first, demand was small; few families could afford second homes, and transportation was difficult. Although vacation home sites would appear to serve the needs of "persons of modest means" even less than would a resort hotel, they were a familiar form of recreation use in the forests. Study showed, however, that the Santeetlah peninsula was unsuitable for vacation homes. Furthermore, the hotel development had "the strong support of the leading citizens of Robbinsville who believe it will make a material contribution to the welfare of their community." [62] The Regional Forester supported the resort development, and by 1947 the land exchange was consummated.

Local political leaders, such as Governor Cherry of North Carolina, also recognized the potential of the National Forests for tourism and recreation. In an October 1947 speech before the Asheville Board of Conservation and Development, the Governor noted that the Forest Service had cooperated with the State in the development of roads to scenic areas in the mountains. Such roads, he believed, would contribute to the growth of tourism and bring money to the State's mountain people. Such cities as Asheville had long profited from tourism, and hoped to profit still more in the postwar years. [63]

|

| Figure 84.—Number of Recreational Visits to All National Forests, 1945-60. Source: Federal Agencies and Outdoor Recreation, ORRRC Study Report 13. A Report to the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission by the Frederic Burk Foundation for Education, Washington, D.C., 1962, pp. 21, 22. A visitor-day=one person for 12 hours, 12 persons for 1 hour, or any equivalent combination. |

How Much Recreational Development?

One of the principal issues relating to postwar recreation was the degree to which the Forest Service should develop recreational facilities. A major advantage of development was that visitors could well become supporters of the National Forests and of conservation. Tourists and picnickers could learn the beauties of these forests, formerly reserved for hunters, fishermen, and a few hikers. A major disadvantage was cost. Even picnic areas and camping grounds required appropriations; elaborate facilities and paved roads were big investments. Should National Forests develop recreation areas or lease concessions for facilities? And, however financed, what types of recreational developments were most appropriate?

In 1947, 168 recreational developed areas had been built in the National Forests of the Southern Region. About half the developments were small—picnic areas and campgrounds. Forty-five of the areas were quite elaborate, some even including swimming pools. Selected recreational areas were considered of outstanding beauty, especially Cliffside on the Nantahala National Forest and North Mills Creek on the Pisgah. Equally well-planned areas in the southern-pine forests of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain were not so attractive or so heavily used. The natural scenic setting of the Southern Appalachian region contributed as much as the planned development to its attractiveness for recreation seekers, and the mountain forests thus had a distinct recreational advantage. [64]

The attractiveness of the Southern Appalachians was demonstrated by recreation cost and use figures for the region. In 1947, less than a third of Region 8's investment in recreation development was devoted to the Appalachian forests, but they had two-thirds of the recreation use in the Region. Many of the recreation areas had been refurbished in 1946 with rehabilitation funds made available in that year to repair the consequences of wartime neglect. [65]

Although the Forest Service developed numerous recreational facilities in the South, and although many questions were arising concerning basic policies, including the types and scale of new recreational development to be pursued, recreation as a form of land use was then not integrated with the resource management plans for either the individual forests or the Southern Region itself. The authors of the Region 8 General Integrating Inspection Reports (men from the Washington headquarters) commented on the development within the Region of master land-use priority plans organized by watersheds. These plans were intended to serve as benchmarks for the formation of resource management plans for the individual ranger districts within each forest. It was considered noteworthy that:

On some areas of the Pisgah District water and game were given priority over timber; in other words, customary cutting practices for the type were to be modified to favor the higher priority uses. We think this is a constructive approach, worthy of active expansion. [66]

|

| Figure 85.—Foot trail beside North Fork of Mills River, a recreation area on Pisgah National Forest between Hendersonville and Asheville, N.C., a short distance from the "Pink Beds," "Cradle of Forestry," and Blue Ridge Parkway, in August 1949. (Forest Service photo F-458635). |

|

| Figure 86.—Boy Scout camp site leased under Forest Service special-use permit at Lake Winfield Scott, a Tennessee Valley Authority power and flood control reservoir on Chattaoochee National Forest, North Georgia, in May 1949. (Forest Service photo F-458505). |

|

| Figure 87.—House trailer camping area in the "Pink Beds," Pisgah National Forest, N.C., in August 1949. (Forest Service photo F-458631). |

|

| Figure 88.—Cherokee National Forest sign on Tellico River Road, Tellico Ranger District, Tenn., May 1957. (Forest Service photo F-486254) |

|

| Figure 89.—Stand of mature white pine and hemlock trees in Laurels Recreation Area, Cherokee National Forest, on Stone Mountain, Unicoi-Carter County line, Unaka Ranger District, near Johnson City, Tenn., in June 1951. Dense tree canopy has provided a park-like atmosphere. Overnight shelters, picnic tables, and toilets are provided here. (Forest Service photo F-469300) |

|

| Figure 90.—Picnicking family at recreation area on Tellico River, Cherokee National Forest, Monroe County, Tenn., in May 1957. Cement tables and benches reduced maintenance and vandalism. (Forest Service photo F-486263) |

Even putting water and game ahead of growing timber was a novel practice at the time, for heavily timbered forests. Policymakers in 1948 were preparing to plan for intensive recreational use in a large number of locations. Comprehensive recreation plans, however, were still in the future.

Thus, to a certain degree, as the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission noted in 1962:

It seems likely that the Forest Service was . . . pushed into recreational activities in self-defense. People discovered the recreational values of the forests and used them with the result that the Forest Service found itself attempting to "manage" recreation to minimize fire hazards, stream pollution, and hazards to the recreationists themselves. Once having become involved, Forest Service personnel apparently adapted themselves to the situation and tried to make the most of it. [67]

In the late 1940's and during the 1950's, facility overuse became critical. As recreational visits to National Forests soared, more funds were provided but not enough for the policing and maintenance necessary. (In 1950, only $2 million were appropriated for all Forest Service recreation—maintenance, construction, and development.) Thus, the problems of roads and parking, litter and refuse, impure drinking water, and fires often became acute. [68]

In the Southern Appalachians, the recreation areas of Bent Creek, near Asheville, and Arrow Wood, outside Franklin, N.C., suffered particularly heavy use and required extra maintenance and patrolling. Throughout the Southern Region, vandalism was "widespread," in some locations "serious." The Forest Service considered night guards or appealing to "decent people in the neighborhood to handle the situation." [69]

Closely related to recreational overuse was the problem of defining who the forests should serve. As early as 1940, the demands of two different publics were noted in a Forest Service document:

Under some circumstances, as in the Talledega country in [northern] Alabama, [near Birmingham] costly recreational developments are primarily designed to serve residents of nearby cities and agricultural valleys, but are very poorly adapted to actual residents living in the "hollows" within the National Forest boundary. But in other instances, the development of simple picnic grounds is greatly appreciated by local residents who are high enough in the economic scale to own vehicles for transportation to such recreational grounds. [70]

These observations could well have been written about the forests of the Southern Appalachians.

In the 1950's, forest officers often accepted unquestioningly the idea that the National Forests were a national possession and belonged to "the people." However, increasingly there were two distinct groups, often with conflicting interests, who could claim to be "the people" to whom the forests belonged. When the needs and interests of recreation users from outside areas came into conflict with those of the local mountain residents, whose interests should come first? Recreation users from urban areas could point out that the National Forests belonged to all the people. Local citizens could argue that the needs of those who resided permanently in the area and made their living in or near the forests should have priority over occasional visitors whose only purpose was pleasure. Most forest officers hoped that the needs of both groups could continue to be met and that they would not have to face the unpopular task of assigning priorities.

|

| Figure 91.—Hikers camping overnight at one of 12 shelters on Appalachian Trail, Nantahala National Forest, N.C., between the Chattahoochee National Forest (Ga.) and Great Smoky Mountains National Park, in July 1960. (Forest Service photo F-494685) |

Woods Burning Remains a Problem

In the Southern Appalachians during the 1950's, management focused on balancing the multiple demands of an expanding public with the needs of the people living in and adjacent to the forests. Fire control, timber sales, and annual fee charges for special-use permits for those dwelling and farming on National Forest land brought the Forest Service and the mountaineer together most frequently.

During the 1930's, as forest officers increasingly found themselves having to deal with people on the forests, they had turned to "people experts" and to occasional careful studies of the local population. Because they saw fire prevention as so vital to the forests in the South, they especially sought the reasons behind deliberate woods burning. Although the Forest Service had had an active program of involving the local population in fire control activities through the fire warden system, forest fires continued to plague forest officers throughout the South. The Forest Service hired a psychologist to study attitudes toward woods burning on one Southern forest, the Talladega in Alabama. He submitted his reports in 1939-40, but their real impact was delayed until wartime activities came to an end. His work was widely distributed and respected, though it was primarily based on study of the people of only one forest. [71]

The psychologist had concluded that the basic cause of fire setting was boredom and frustration among the local people. He noted the role of tradition in passing, as in the title of his article "Our Pappies Burned the Woods," but his cure for fire setting was a plan to alleviate boredom. His principal recommendation was the creation of community centers for social, recreational, and educational purposes. Compared to other studies of the mountaineer personality, his work seems superficial and his policy recommendations were of doubtful value. There were certainly similarities between the people of the Alabama hills and those of the Southern Appalachian mountains, but there were as many differences. Even among the forests covered by this study, there were quite noticeable differences in the people and their attitudes, especially on the question of use and control of fire. There were differences between those who lived on the older forests and those in the new forest areas established in the 1930's.

The psychologist stated his conclusions in broad terms:

The roots of the fire problem obviously go deep into the culture, the traditions and the customs of these people and their frustrated lives. It is well established in psychology that groups and individuals when frustrated express themselves by harmful acts, called aggression, either against other humans or against their environment . . . These intentional fires of the malicious type, however, are in the minority. Non malicious woods-buring constitutes the major cause growing out of a survival of the pioneer agrarian culture originally based on economic grounds. With the closing in of the agrarian environment, it has become predominantly a recreational and emotional impulse . . . The sight and sound and odor of burning woods provide excitement for a people who dwell in an environment of low stimulation and who quite naturally crave excitement. Fire gives them distinct emotional satisfactions which they strive to explain away by pseudo-economic reasons that spring from defensive beliefs. Their explanations that woods fires kill off snakes, boll weevils and serve other economic ends are something more than mere ignorance. They are the defensive beliefs of a disadvantaged culture group. [72]

|

| Figure 92.—Steel lookout tower on Black Mountain near Woody Gap, Suches. Ga.. on Chattahoochee National Forest, December 1952. Chestatee (formerly Blue Ridge) Ranger District. (Forest Service photo F-470980) |

Noteworthy was the study's refusal to accept the reasons for woods burning given by the people themselves, and the apparent assumption that woods burning was important to the people. The study was made because fire prevention was a major aim of the Forest Service in the South, but whether it was really important to the woods-burners was not clearly determined. Were the fires subsidiary results of brush clearing or hunting? Or were they considered a necessary part of life to southern rural people?

A more modest study carried out by a forest officer at about the same time covered three of the mountain forests, Cherokee, Chattahoochee, and Nantahala. Interviewing 39 heads of households whose lands were contiguous to, or surrounded by, Government-owned land, he asked a number of questions related to policies and management of the forests. Fire prevention was an important aspect, but he was concerned with more than woods burning. Trying to determine which Forest Service goals meant most to the people, he found:

Maintenance of timber resources and employment meant most to eighteen, or slightly more than half. The wildlife . . . appealed most to eight, saving of land to six, and forest attractiveness to three. Many persons well acquainted with these people affirm that their interest in wildlife and hunting transcends everything else. The expressions here show, however, that aspects of the forest program promising more opportunities for employment have the stronger appeal. [73]

|

| Figure 93.—A Forest Service crew clearing a fireline before setting light to a backfire to stop the Laurel Branch wildfire which was racing toward them. Campbell Creek, Watauga Ranger District, Cherokee National Forest. Tenn., November 1952. (Forest Service photo F-471193) |

The investigation also showed the fire causes most familiar to them: farmers' burning brush or fields, campfires, smoking of "bee trees," and other "accidents." The purpose of starting a fire was not to burn the forest, but little was often done to keep the fire from spreading. They did not think people should be prosecuted for such accidents, but most of them agreed that intentional fire setters should be penalized.

One significant but not surprising finding was that each person tended to evaluate the National Forest and its programs by how he or she personally was affected. For the most part, respondents were satisfied with the forests in their localities, but:

The specific comments they made showed their appraisal to be in terms of grazing, prices paid for land, timber sales, and other matters in which they see themselves affected economically at present, and to no small extent, the likableness of forest officers they happen to know. The broader purposes of national forest management appeared to be unfamiliar lines of thought to most of these backhills people. [74]

|

| Figure 94.—Crewmen on the fireline using specially made triangular-toothed rakes to prevent their newly lit backfire from spreading across the line to unburned timber. Laurel Branch Fire, Watauga Ranger District, Cherokee National Forest, Tenn., November 1952. (Forest Service photo F-471196) |

A majority favored enlarging the National Forests in the mountains. Those who disagreed feared that families would be forced to leave and would have no way of getting along in new homes. The diversity of responses found in these interviews and the tendency of the mountain people to make judgments on a very personal basis seem most striking. The study made a number of recommendations for improving public relations, but proposed no overall plan or cure for problems with forest neighbors.

How widely these and other studies of the local people were read and believed by the forest officers is a question that cannot be answered, but the existence of these studies reflects official concern, beginning in the late 1930's, for developing insights into the behavior of rural Southerners. Although this concern persisted, it generally focused on the pine forests of the deep South, where burning could be beneficial if properly done. Man-caused fires were certainly not gone from the mountains, but the more severe problems often came from other areas. [75]

|

| Figure 95.—A fire crewman keeps a close watch on a burning snag (dead tree), to prevent embers from spreading across fireline to untouched timber. Laurel Branch Fire, Watauga Ranger District, Cherokee National Forest, Tenn., November 1952. (Forest Service photo F-471197) |

Timber Sales Favor Small Logger

Throughout the National Forests, but in the Southern Appalachians in particular, timber sale policy continued to favor the small logger. The Forest Service regarded such sales as a direct means of benefiting and influencing the local public. According to an internal document dated August 1940, "much emphasis is put on making sales to the little fellow who has only the most meager equipment and can only raise a few dollars for advance payment." [76]

Indeed, the "little fellow" had come to dominate the lumber industry in the Southern Appalachians. Throughout the 1940's and 1950's small portable sawmills became more and more prevalent, and sawmilling in general became a seasonal or intermittent industry, employing only a few men. In 1954, about 90 percent of lumber operations throughout the region reported fewer than 20 employees. [77] The largest commercial logging operations were concentrated in the coal-producing counties of eastern Kentucky, particularly Harlan, Leslie, and Perry. [78]

Small sawmill operators on the Cumberland National Forest responded favorably to the agency's timber sale policies. An interview conducted during the mid-1950's of eastern Kentucky wood processors revealed a positive, even enthusiastic, attitude toward the Cumberland:

With few exceptions, the Cumberland National Forest received general acclaim, even among those wood processors who added that they didn't buy there because too much of the lumber was fire scarred, or because "the system was too elaborate," or, more generally, because the lumber was poor or to a "different measure." Enthusiasm was greatest in the north, where the National Forest was said to be "a life saver to this area," "wonderful," "helping a lot." [79]

At the same time, attitudes toward private timber holders were unfavorable. They were criticized for carelessness concerning fires and a lack of initiative in reforestation. Ironically, however, most of those interviewed confessed to making no direct efforts themselves toward systematic reforestation. [80]

Timber sales from the National Forests were important not just for the employment and profits they offered the local wood processors, but also for their contribution to National Forest revenues. Under the Weeks Act, 25 percent of such revenues (from the so-called 25-percent fund) were returned to the States for recommended distribution to the counties for schools and roads, proportional to the National Forest acreage in each county. [81] Since timber sales were the principal component of National Forest revenues, their size and number influenced the fiscal well-being of whatever counties were involved.

|

| Figure 96.—Hog Branch timber sale being discussed at portable mill site by Henry Parrott, right, of Bond, Ky., operator, and Berea District Assistant Ranger Paul Gilreath, in July 1955. (Forest Service photo F-478903) |

The 25-Percent Fund

The writers evaluated the Forest Service's recommended payments from the 25-percent fund, 1940-60, to the 12 Southern Appalachian counties selected in this study for detailed analysis. This showed considerable changes in timber sales and timber sale revenues, as well as increases in timber prices over this period. [82] It also illustrated several of the problems with the Forest Service's 25-percent payments as a source of county revenue.

Our analysis considered 25-percent payments and National Forest acreage per county for the nine counties of the group having such acreage. (Hancock and Buchanan Counties have no National Forest acreage; before 1972, Knox County had none.) For all nine counties, 25-percent payments and payments per acre increased from 1940 to 1960. Gross payments increased many times over—for example, from $1,658 in 1940 to $22,302 in 1960 for Union County. However, in 1960 even the highest paid county, Macon, received only $34,679 from the fund. As a supplemental payment for roads and schools, the 25-percent fund was still certainly not large.