|

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81 |

|

Chapter VII

Federal Development of the Southern Appalachians, 1960-81

Under the presidencies of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the Appalachian region was recognized as seriously lagging behind the rest of the Nation, and concerted efforts were directed at revitalizing the area's economy. A myriad of Federal programs were developed to combat poverty and unemployment, some aimed specifically at Appalachia. The Appalachian Regional Commission, created by Kennedy in 1963, and given expanded powers by Congress in 1965, funneled millions of dollars into the Southern Appalachians. In addition, Federal land acquisition in the area was given new impetus, and a new National Forest purchase unit was created in eastern Kentucky. The National Forests of the region were pressured to market their resources to help meet accelerating demands for timber nationwide. Although the region made gains in employment, health, and education, the Southern Appalachian mountaineer, in the early 1970's, remained considerably poorer and less advantaged than the average American in spite of multiple Federal development efforts.

When John F. Kennedy campaigned in the West Virginia Democratic primary for the presidency in April and May 1960, the poverty and squalor he witnessed made a strong impression on him. [1] One of his earliest concerns as President was to ease the depressed conditions he had seen and to restore the Appalachian region to economic health. Shortly after taking office, Kennedy appointed a Task Force on Area Redevelopment to deal with the problems of chronic unemployment, unused labor, and low income. The recommendations of the Task Force, published in early January 1961, echoed New Deal proposals of 30 years before: emergency public works programs in depressed areas of the Nation and development of these areas' natural resources.

|

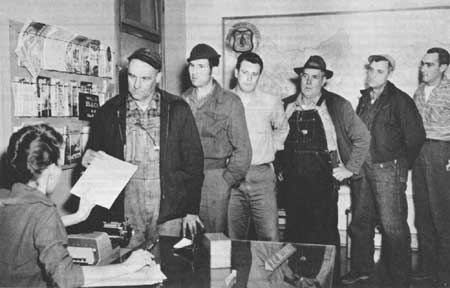

| Figure 99.—Local unemployed workers applying for forestry jobs under the Federal Accelerated Public Works (APW) Program in the Tusquitee Ranger District office, Nantahala National Forest, in Murphy, Cherokee County, N.C., in January 1963. APW ran for 2 years and led to the myriad programs of the Economic Opportunity Act. (Forest Service photo F-503999) |

Appalachia Is Rediscovered

The year 1960 thus marked the beginning of a national rediscovery of Appalachia that directed billions of Federal dollars to improving the area. Specifically, the Kennedy Task Force identified nearly 100 Appalachian "depressed areas," classified by the Department of Labor as having a "labor surplus, substantial and persistent," and between 300 and 400 rural, low-income areas where Federal funds might be concentrated. The Task Force report recommended that a commission be established for the 11-State Appalachian region to tackle special area development problems. Although most of these recommendations were not translated into Federal action until the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, John F. Kennedy redirected national attention and concern to the region. [2] He appointed an advisory commission in 1963.

In 1960 the Appalachian region certainly deserved national attention. Since World War II, as its agriculture and coal industry failed to keep pace with national trends, its population was increasingly unemployed and poor. By 1960, the region's employment, income, and educational levels were well below the national averages. Although the State of West Virginia represented one of the worst concentrations of regional poverty, Appalachian Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia also suffered severe underemployment and income inequities.

As discussed in some detail in chapter VI, the Southern Appalachian region had been experiencing heavy outmigration for two decades. At the same time, human fertility rates were declining, so that by 1960 the natural rate of increase (births minus deaths per 1,000 population) was not enough to offset the population losses from net outmigration. Not only was population declining, but relatively more was age 65 or older. Throughout the southern mountains, more and more people were leaving their farms for urban and suburban areas. However, retailing and manufacturing firms could not absorb the extra labor, and unemployment rose, In 1960, the unemployment rate of Appalachia was nearly twice the national average. [3]

By whatever statistic it was measured, the poverty of the region was glaring. In the counties of Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission to be part of "Appalachia," poverty was reflected in per capita income figures, poverty level statistics, infant mortality rates, and school enrollments. Four such measures are presented in table 9.

Table 9.—Four poverty indicators in the Appalachian Mountain sections of five Southern States, circa 1960

| Per capita income as percentage of U.S. average—1965 |

Percentage of households below poverty level—1960 |

Infant mortality rate per 1,000—1960 |

Percentage of persons 16-17 not enrolled in school—1960 | |

| United States | 100 | 22.1 | 26.0 | 19.1 |

| Appalachian Kentucky | 49 | 58.4 | 30.9 | 33.0 |

| Appalachian Virginia | 55 | 24.4 | 31.0 | 33.1 |

| Appalachian Tennessee | 70 | 39.9 | 27.7 | 27.9 |

| Appalachian North Carolina | 75 | 37.2 | 26.8 | 25.6 |

| Appalachian Georgia | 70 | 38.5 | 29.1 | 28.0 |

Source: Compiled from Appalachia—A Reference Book (Appalachian Regional Commission, February 1979).

The table shows that, by all four measures, the people of the Southern Appalachians in 1960 were poorer, less healthy, and less well educated than the national average. This was especially true in Appalachian Kentucky where per capita income was only half the U.S. average, and nearly three times the national percentage of families were below poverty level. The infant mortality rate, as an indicator of general health conditions, was highest in Appalachian Virginia and Kentucky, which also had the most 16- and 17-year-olds not enrolled in school. Thus, the statistics confirm that, in general, conditions in the coal counties were the most severe, although throughout the region poverty was markedly worse than the national average.

These conditions were examined more closely for the 12 study counties selected for detailed analysis and introduced in chapter VI. Five poverty indicators available from 1960 Census data are presented for the 12 counties in table 10. On a county-by-county basis, the greatest discrepancies in the data appear between the Cumberland Plateau coal counties of McCreary and Knox in Kentucky, and Hancock, in Tennessee, as a group, and the remaining mountain counties. In 1960, these three had by far the lowest income of the 12 and the most families below poverty level. Also, along with Union County, Ga., they had the most on public assistance and, along with Graham County, N.C., the fewest earning $10,000 a year or more.

Table 10.—Five poverty indicators in 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties, circa 1960

| High proportion of National Forest | Little or no National Forest | |||||||||||||

| Poverty Indicator | Union, Ga. | Graham, N.C. | Macon, N.C. | Unicoi, Tenn. | McCreary, Ky. | Bland, Va. | Six-county weighed average* | Habersham, Ga. | Ashe, N.C. | Henderson, N.C. | Hancock, Tenn. | Knox, Ky. | Buchanan, Va. | Six-county weighed average* |

| Per capita income—$ | 768 | 770 | 870 | 1,127 | 481 | 836 | 809 | 1,104 | 759 | 1355 | 516 | 594 | 844 | 862 |

| Percentage of families below poverty level | 67.1 | 58.0 | 56.2 | 39.6 | 71.5 | 56.2 | 58.1 | 35.5 | 60.9 | 35.5 | 78.0 | 70.5 | 50.2 | 55.1 |

| Percentage of population receiving public assistance** | 8.8 | 5.9 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 13.3 | Under 1.0 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 7.7 | 2.3 | 8.7 | 11.7 | 2.3 | 5.4 |

| Percentage of families with incomes of $10,000 or more | 3.1 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 6.4 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| Percentage of population 65 years or older | 10.2 | 7.6 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 11.8 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 4.0 | 8.6 |

*For percent of families below poverty level, averages are unweighted.

**1964 recipients as a percent of 1960 population.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, City and County Data Book (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1962, 1967).

L. E. Perry has painted a more explicit picture of conditions in 1960 in McCreary County, representative of the Cumberland Plateau in Kentucky, which has a high percentage of National Forest land:

The county was not the best in economic stability (it never seems to be) nor was it the worst. But the general welfare of the people was disturbing. . . . There were the same crucial and urgent problems. 49% of all homes had no running water; 65% of the homes had no bathrooms; 75% had no central heat; 33% of the homes were on dirt roads. Hundreds of unsightly, unsanitary and uncomfortable houses dotted the landscape. The problems of housing and what to do about it was one to stagger the imagination. . . . [sic.]

Surplus food distribution was not only a way of life it was life for much of the population, not unlike the never-to-be-forgotten days of the great depression.

The slump in coal production in the 1950s persisted; the war-time factories no longer beckoned. Unemployment was at a high rate. Would poverty never perish in McCreary County? [4]

A comparison of the six study counties with a high proportion of National Forest land and those with little or no National Forest suggests that the former group fared worse in 1960—but only slightly so. The averages computed for each set of counties are generally close, with only several percentage points between them, except for a larger difference in the percent of population earning $10,000 or more. It is noteworthy that within each group of counties—and excluding the Cumberland coal counties—the differences are considerable. For example, Unicoi and Union Counties, with 43 and 47 percent, respectively, of their land in National Forests in 1960, showed a difference of 32 percent in per capita income. Similarly, Henderson and Ashe Counties, with only an 8 percent difference in National Forest land ownership in 1960, had a 44 percent difference in per capita income.

Thus, it appears that in 1960, although the six counties with a higher proportion of land in National Forests were generally poorer, had a higher percentage of people dependent on public assistance, and a higher percentage of people 65 or older than the six counties with a low percentage of National Forest ownership, these differences were relatively small. These differences were not so great as those within the two sets of counties studied and across the subregions of the Southern Appalachians. Thus, it cannot fairly be determined from this sample whether a high proportion of National Forest land depressed local social and economic conditions. Certainly, poverty conditions cannot be attributed to Federal landownership alone, if, indeed, to any degree at all.

The first emergency employment project for distressed areas to be implemented under President Kennedy was the Accelerated Public Works Program (APW) which operated nationwide during the 1962 and 1963 fiscal years under a $900-million authorization of the Clark-Blatnik Emergency Public Works Acceleration Act enacted September 14, 1962. Funds were allocated by the Area Redevelopment Administration in the Department of Commerce. During the 2 years, a peak force of 9,000 men worked on a multitude of projects on 100 National Forests, advanced with $60,800,000 of allotted funds, many in the Southern Appalachians. (See table 11.) Work included picnic and camp recreation and sanitary facilities, timber stand improvement, wildlife and fish habitat improvement, roads and trails, erosion control, and fire towers, ranger offices, warehouses, and other structures. Among the latter were a new office for the Morehead Ranger District, Daniel Boone National Forest, Ky., and construction of research facilities for water runoff measurement at the Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory near Franklin, N.C., in the Nantahala National Forest. [5] The APW Program led to the numerous special work programs of the Johnson Administration which developed out of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964.

Table 11.—Allocations of funds to National Forests in the Southern Appalachians under the Accelerated Public Works Program, 1962-64

| 1962-63 allocations (dollars) total: 32,500,000 |

1963-64 allocations (dollars) total: 28,300,000 | ||||

| Area | First | Second | Third | First | Second |

| All National Forests | 15,000,000 | 10,000,000 | 7,500,000 | 20,255,000 | 8,045,000 |

| Southern Appalachian Forests | 980,000 | 1,700,000 | NA | 2,435,000 | NA |

| Chattahoochee and Oconee (Georgia) | 200,000 | 410,000 | NA | 600,000 | NA |

| Cherokee (Tennessee) | 180,000 | 300,000 | NA | 285,000 | NA |

| Daniel Boone (Kentucky) | 350,000 | 145,000 | NA | 545,000 | NA |

| Jefferson (Virginia) | 50,000 | 260,000 | NA | 485,000 | NA |

| Pisgah, Nantahala, Uwharrie, and Croatan (North Carolina) | 200,000 | 485,000 | NA | 520,000 | NA |

Note: NA = Not available

Total Funds, 1962-64, all National Forests: $60,800,000

Funds listed include amounts tot States for tree planting

Source: Accelerated Public Works file, History Section, Forest Service

The Federal War on Appalachian Poverty

When Lyndon B. Johnson became President in 1963, he turned Kennedy's concern with poverty and unemployment into a crusade: a "War on Poverty." Over the next 5 years, a proliferation of governmental agencies and programs was created to combat the nation's economic ills. The Southern Appalachians were "rediscovered," and a substantial share of Federal program money was provided for the region's development. [6] As L. E. Perry put it:

Every big gun was pointed toward Appalachia and there were dozens of them in the armies of agencies recruited to fight poverty. There was an Accelerated Public Works Program and the Area Redevelopment Administration with numerous projects to disperse the federal benefits. Another division was called Manpower Development and Training Act. Only the bureaucrats knew the meaning of that. There was action in the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and the mighty Agriculture Department. The Appalachian Road Program was pushed forward and the Forest Service revived a nearly dead land acquisition program. Even the Kentucky Department of Economic Security was in the midst of this war. Every conceivable maneuver, it seemed, was anticipated, and covered by some sort of program or plan at the local, State or federal level.

But the top brass was that of the Office of Economic Opportunity. Here was the command post of such powerful agencies as Head Start, Neighborhood Youth Corps, Job Corps, Vista, Unemployed Fathers (Happy Pappy) and others. If poverty could not be eliminated, this war would make it more enjoyable. [7]

The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 created many of the most visible programs throughout Appalachia, [8] incorporating several antipoverty approaches. The Act established a series of unconnected programs under the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). These included: Community Action Programs, Job Corps, Neighborhood Youth Corps, VISTA (Volunteers In Service To America), Summer Head Start, and the Work Experience and Training Program. In fiscal years 1967 and 1968 alone, OEO spent nearly $225 million in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia, mostly on Community Action Programs, but much on Head Start and Job Corps also. VISTA, although more publicized, received only 2 percent of OEO funds for 1967 and 1968 in the five States. [9]

Another visible OEO program in Appalachia was President Johnson's Work Experience and Training Program, operated by the Department of Labor. It provided on-the-job training for unemployed fathers of dependent children who would otherwise receive AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) payments. Popularly known as the "Happy Pappy" program, it was very active in eastern Kentucky, where it at first inspired enthusiasm. In 1965 William McKinley Sizemore, mountain resident of Knox County, Ky., volunteered the following folk song about the Happy Pappy program:

Mr. Johnson put me to working

When he signed that little bill

Since I've become important

It gives me a thrill

The neighbors hushed their talking

That I was no good

Since I'm a happy pappy

They treat me like they should. [10]

However, although for some mountaineers this program may have made Lyndon Johnson the favorite President since Roosevelt, it soon brought on widespread cynicism and disillusionment. By 1967, even before the Nixon administration, funds for the program were severely cut back. [11]

VISTA and most other OEO programs suffered similar fates. Basically, they were criticized for being naively and expensively staffed by people with grand ideas but little practical experience. OEO was repeatedly charged with spending dollars to "fatten middle-class staffs as assistant directors and executive secretaries proliferate." [12] Part of the failure of VISTA, it was claimed, rested with Appalachian Volunteers, Inc., (AV) an organization of about 30 persons supported almost entirely by OEO grants, which managed VISTA initiatives. AV, it was charged, lacked management skill and was generally not cost-effective, [13] (Of the 12 study counties, only Knox, McCreary, Hancock, and Macon received any VISTA funds.) [14]

Job Corps Proves Itself

One of the few OEO programs that survived the 1960's relatively uncriticized was Job Corps, which grew out of a recommendation of the 1961 Kennedy Task Force and was still going strong 20 years later. A supplemental appropriation to the Forest Service was recommended for timber stand improvement, control of erosion, and development of recreation facilities on National Forests in distressed areas, many of which were in the Southern Appalachians. [15] One of the main aims, as with the CCC, was to create jobs to absorb the unused young labor of such areas.

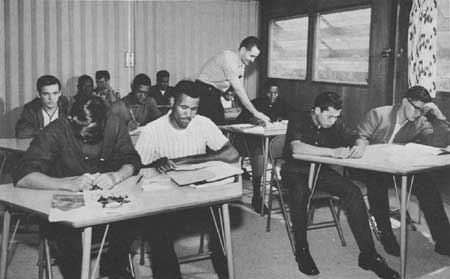

This recommendation was translated into Job Corps during Lyndon Johnson's presidency by the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, funded in the Department of Labor. Job Corps was intended to provide intensive educational and vocational training in group settings for disadvantaged youth so that they might become responsible and productive, and to do so in a way that contributed to national resource development. [16] Certain Job Corps camps were to be operated by the Forest Service as Civilian Conservation Centers under an inter-agency agreement with the Department of Labor. As L. E. Perry said, ". . . Job Corps was the new baby the Forest Service had long wanted but could not afford until the OEO stork arrived." [17] The first Job Corps center to be activated in the United States, Camp Arrow Wood, opened in the Nantahala National Forest near the town of Franklin, Macon County, N.C., early in 1965. (It was renamed Lyndon B. Johnson after his death.) Five other camps opened later that year throughout the Southern Appalachians. Most were old CCC camps, remodeled and made habitable by the Corpsmen themselves. The six Southern Appalachian Job Corps (Civilian Conservation) centers still active in 1982 are listed below.

Table 12.—Civilian Conservation Centers* in National Forests of the Southern Appalachians, 1980 and 1982

| National Forest | Camp | Trainee Capacity | |

| Fiscal year 1980 | Fiscal year 1982 | ||

| Nantahala, N. C. | Lyndon B. Johnson (formerly Arrow Wood) | 205 | 205 |

| Pisgah, N. C. | Schenck | 224 | 224 |

| Cherokee, Tenn. | Jacobs Creek | 200 | 224 |

| Jefferson, Va. | Flatwoods | 224 | 224 |

| Daniel Boone, Ky. | Pine Knot | 224 | 224 |

| Frenchburg | 224 | 168 | |

*Originally called Job Corps Centers

Source: Harold Debord, Human Resource Programs, Southern Regional Office, Forest Service, Atlanta, Ga.

The purpose of Job Corps was to transfer disadvantaged, primarily urban, youths to new environments where they would receive vocational training, education, and counseling. The Corpsmen who were sent to the Southern Appalachian centers were predominantly urban and black. When Job Corps began, the introduction of several hundred black youths into a previously all-white mountain community caused some problems. In some locations, it was difficult to integrate the Corpsmen into the surrounding communities as easily as had been hoped.

|

| Figure 100—New Stearns Ranger District office and modern sign, with Rangers Andrew Griffith and Herbert Staidle by official car in front, on State route 27, Daniel Boone National Forest. Ky., in July 1966. Name of Forest had just been changed from Cumberland in April. (Forest Service photo F-515412) |

For example, a 1966 review of community attitudes toward the Schenck Job Corps Conservation Center located in the Pisgah National Forest showed some local reluctance to welcome the men. Although nearby Hendersonville had invited them to visit certain prearranged, select sites, the town would not send its representatives to the camp, "not wishing to have their presence [in general] or deal with their problems. This has been made formally clear." [18] The small town of Brevard, only a few miles from the camp, was felt to offer little for the urban youth. Asheville, where they were bussed regularly, seemed to know little about the camp. The Asheville police were said to "regard the influx [of Corpsmen] in a most informal manner, looking the other way when small disturbances occur." [19]

The worst Job Corps problems in the Southern Appalachians were at Arrow Wood. In 1965, after a busload of Corpsmen arrived in Franklin, N. C., for a summer evening, violence erupted between them and some local ruffians. According to the Camp's first director, although local youths had caused disturbances with outsiders before, this evening's melee was unprecedented. Police stopped the violence, and many local boys spent the night in jail. After that evening, policies changed; the number of Corpsmen bussed into Franklin was kept to a minimum. [20]

Fortunately, such racial disturbances were not widespread. Camps near towns larger than Franklin had less difficulty. For example, Jacobs Creek Center near Bristol, on the Tennessee-Virginia line, experienced no such problems. It seems that Bristol, a bi-State city of 55,000, with a black population of its own, was better able to absorb the Corpsmen. [21]

The Pine Knot Job Corps Center, which opened in McCreary County in 1965, likewise experienced no racial difficultures. L. E. Perry wrote of its establishment:

At first the government officials were apprehensive about the possible racial consequences of establishing the training center in the area of McCreary County since it would recruit a majority of young blacks. After several local civic group meetings in the county, and with considerable preconditioning statements, it was generally implied that no more than 50% of the trainees would be of the minority class.

The local people for the most part have no preconceived ideas about racial discrimination and they refused to act violently. Within a few years the Center was almost 100% made up of black youths in training with a staff that was 100% white. The Forest Service hierarchy was pleased at the non-violent acceptance of the blacks by the citizens and privately and gleefully congratulated one another for integrating McCreary County without conflict. [22]

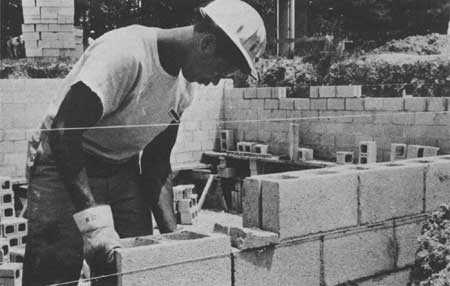

Over the years, Job Corps has improved the National Forests of the Southern Appalachians in much the way the Civilian Conservation Corps did 30 years before—with road construction, construction of recreational facilities, soil erosion control, reforestation, and timber stand improvement. For example, the ranger station and the visitor center of the Cradle of Forestry in Pisgah National Forest were built by the Schenck Job Corpsmen. [23]

Some of the Corps work has benefited local communities as well as the forests. In 1979, for example, the Pine Knot Job Corps unit rebuilt the McCreary County Little League baseball field, constructed a backstop and chain-link fence for the McCreary County Park, and supplied umpires for local Little League games. [24] Job Corps centers have also provided employment for local residents, either through the construction of facilities for the centers or through staff positions. For example, in 1979 the Frenchburg Job Corps center in the Daniel Boone Forest employed between 30 and 40 persons from Powell, Montgomery, Menifee, and Bath counties on construction contracts, and employed 22 persons full time and 8 persons part time as center staff members, also from adjacent counties. The Center director estimated that 70 percent of Frenchburg's nearly $1 million operating budget was spent in the five-county area surrounding the center. [25]

|

| Figure 101.—Classroom instruction in basics for Job Corpsmen at Schenck Conservation Center near "Cradle of Forestry" on Pisgah National Forest near Brevard, N.C., in August 1966. (Forest Service photo F-516105) |

Other Programs Benefit Local Labor

The other Human Resource Programs administered by the Forest Service have had a more direct impact on the local labor market in the Southern Appalachians. The Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) and Senior Conservation Employment Program, both initiated in 1971, have provided employment in the National Forests for local youths and elders. YCC has operated summer camps for male and female youths 15 to 18, enrolling as many as 1,200 persons per year in the Southern Appalachians. Although YCC youths are not necessarily local, the locals who do enroll often are children of business and professional leaders in the community. [26] YCC campers have built trails, planted trees, developed campgrounds, and surveyed land throughout the Appalachian forests. In 1981 YCC was reduced but continued on a revised basis.

The Senior Conservation (older American) Employment Program has provided work at minimum wage for over 500 elderly folk in the National Forests of the southern mountains. They have been local men and women 55 or older, with no income except Social Security or small pensions, performing odd construction and repair jobs. The program has been considered highly successful in involving the local population in Forest Service activities, and in furthering rapport with the local community. [27]

The Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC), begun in 1977, is the most recent Human Resource Program. It has provided employment at minimum wage for a 1-year maximum to local men and women between 16 and 23 years old. Unlike Job Corps and YCC, persons in YACC lived at home; mostly on the fringes of the National Forests. In 1979, nearly 500 persons were employed in YACC in the Southern Appalachian National Forests—including 112 in the Daniel Boone alone. [28] In 1981 this program was terminated by the new administration in Washington in an economy move.

|

| Figure 102.—Job Corps trainees on way to morning classroom and field work assignments at Schenck Conservation Center, Pisgah National Forest near Brevard, N.C., August 1966. (Forest Service photo F-516130) |

The Appalachian Regional Commission

In 1965 President Lyndon Johnson secured passage of the Appalachian Regional Development Act, which created the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). [29] A study commission, originally recommended by the Kennedy Task Force, had already been in operation for 2 years under presidential appointment. Under the leadership of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr., the President's Appalachian Regional Commission (PARC) had conducted several analyses of the region, and had formulated the commission's essential approach to regional development. [30]

The main problems of Appalachia were defined by PARC as a lack of access both to and within the region, a technological inability to use its natural resources fully, a lack of facilities to control and exploit its rainfall, and inadequate resources to train its youth. [31] Thus, regional development was to focus on a new and improved highway network; public facilities; resource development programs for water, timber, and coal; and on human resource programs. Specifically in regard to the Appalachian timber resource, PARC viewed the region's timber as underutilized and undermarketed, and recommended that increased timber harvesting would not only provide local jobs, but would also improve conditions for recreation, wildlife, and water production.

The Appalachian Regional Commission, created in March 1965, consisted of the governors of 12 Southeastern and Northeastern States (the 13th State, non-Appalachian Mississippi, was added in 1967) and one presidential appointee. The Commission was to coordinate the administration of a great new Federal-State funding effort for Appalachian development. Although most supporting funds would be Federal, the burden of the responsibility for project initiation, decisionmaking, and program administration was delegated to the States. In this delegation, ARC represented a new approach to regional rehabilitation efforts.

The Commission defined "Appalachia" as a vast 195,000-square mile region of 397 counties, including all of West Virginia and parts of 12 other States from New York to Mississippi. On the assumption that Appalachia, as "a region apart," lacked access to the Nation's economic system, and that correcting this defect was basic to the entire program, the main initial thrust of the commission's development effort was to improve the region's system of highways. In fact, more than 80 percent of the first ARC billion-dollar appropriation was for a Development Highway System, the money to be spent over 6 years. [32] Among the improvements resulting were the Foothills Parkway along the Tennessee side of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the Tennessee portion of the Tellico Plains-Robbinsville Highway across the Smokies south of the Park, and the Bert T. Combs Mountain Parkway from Winchester to Salyersville, Ky., through the Red River Gorge. Other public works investments were planned, but human resource development was left to the poverty programs administered under OEO, and even natural resource development was regulated to low priority, as Robb Burlage described it:

The Act [Appalachian Regional Development Act] explicitly forbade use of public funds to purchase or support public power and ignored most direct agency resource development and administrative powers. Water resources were given to the Congressional (and private power company) favorite, the Army Corps of Engineers, to study and plan with the states for five years. Timber, livestock, and mineral development programs were whittled away. Environmental control over coal was narrowed to a few restoration and study efforts. [33]

ARC funds were to be concentrated in those areas of the region that had fared relatively well during times of economic distress and thus showed a potential for self-sustaining growth. The highway network would connect all such growth areas, and provide access to them from the surrounding labor fields. Jerald Ter Horst said there was "a hint of economic predestination" in ARC's development premise: "the belief that many economically weak towns and counties do not have the potential to become thriving, prosperous centers of population." [34] When eastern Kentucky newspaper editor Tom Gish saw an ARC development map in December 1964, showing only white space for his area, he labeled it "Eastern Kentucky's White Christmas." [35]

|

| Figure 103.—Job Corpsman receiving instruction in operating heavy road building equipment from officer of Pisgah National Forest, N.C., in August 1966. (Forest Service photo F-516209) |

Local Development Districts

For administrative purposes, the States divided their Appalachian regions into local development districts (LDD's), of which there were 69 in 1980. LDD's are multicounty planning and development agencies organized around urban growth centers. For example, the Southwest North Carolina LDD encompasses Cherokee, Clay, Macon, Graham, Swain, Jackson, and Haywood Counties. LDD's receive administrative support funding from ARC but operate differently from State to State. Projects are often initiated and administered LDD wide, although others are restricted to one county or encompass several LDD's.

The programs funded through the Appalachian Regional Commission have been administered through a series of existing governmental agencies, often co-sponsored by them. ARC developed working relationships with a number of Federal agencies active in the region; for example, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Rural Development and Soil Conservation Services of the Department of Agriculture. Although ARC's relationship with the Forest Service has been less formalized than those with other Federal agencies, there has been communication between the two on certain initiatives and policy issues. The commission has funded a series of resource and environmental programs, primarily in mine subsidence, land stabilization, and mine reclamation, There have been timber development programs as well, although very localized and small in scale; this is discussed further on. ARC has funded, through the Forest Service Regional Office in Atlanta, several associations of landowners for the purpose of private timber development. In 1980 one was operative in a five-county area around Catlettsburg, Ky. [36]

|

| Figure 104.—Cinder blocks for new office building of Stanton (formerly Red River) Ranger District being laid by Job Coops trainee in June 1967. The men on this project were from the Frenchburg Civilian Conservation Center, near the Red River Gorge and the confluence of Menifee, Powell, and Wolfe counties, on the Daniel Boone National Forest, Ky. (Forest Service photo F-519122) |

ARC Is Criticized For Falling the Poor

Between 1966 and 1978, the Appalachian Regional Commission spent more than $3.5 billion for the region's economic development. [37] Although the Commission has cited numerous successful projects, critics—from the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) to local spokesmen, such as Robb Burlage and John Gaventa—have been vocal. In essence, they charged that ARC has failed to reach the region's critically poor, and that "improvement" has benefited only the local elites or the already urbanized areas of Appalachia. Over 60 percent of ARC's funds have gone into highway building or improvement. [38] Of the remaining funds that have been dispensed, most have bypassed the hard-core, neediest Appalachian communities. Several have suggested that to be truly responsive, ARC should have recognized Appalachia's status as an internal colony by taxing the coal and resource extraction industries, fostering the development of public power, and encouraging greater local citizen participation in the Commission's expenditure decisions, [39]

The General Accounting Office, in an April 1979 report to Congress, was more specific in its criticisms. In essence, the GAO found that, (1) the fundamental goals of ARC were not completely clear; (2) ARC State-planning efforts were politically oriented, fragmentary, and inadequate; (3) specific time frames for the accomplishment of the Commission's long term goals had not been established; (4) often areas with the least severe poverty and employment problems had received the highest average ARC funds per capita; and (5) that funding and program status had frequently not been adequately monitored. [40]

The report specifically focused on the Kentucky River Area Development District of central eastern Kentucky, which includes Leslie, Perry, Knott, Owsley, Breathitt, Wolfe, and Lee counties—most of which are in the area of this study. The GAO concluded that, in spite of concentrated investments of nearly $23 million in the district, and in spite of the district's percentage increase in per-capita income greater than the national average, the incidence of poverty worsened for the district between 1960 and 1970. Thus, the GAO questioned "whether the goal of economic self-sufficiency is feasible or realistic in this and perhaps other parts of Central Appalachia." [41]

Out of the more than $3.5 billion in ARC funds expended between 1966 and 1980, slightly more than $230 million were spent for single counties over the 84-county area considered in this study. [42] For four of the five States involved—Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia—ARC funds were spent fairly evenly on a per-county basis. The Virginia counties, however, received about twice the per-county ARC funds (over $4.6 million) as did the others.

Counties that received the most ARC funds individually (more than $6 million) over the 84-county area are listed below.

Table 13—Southern Appalachian counties receiving most ARC funds, 1966-80

| Wise County, Va. | $13,029,646 |

| Whitfield County, Ga. | 10,530,783 |

| Buncombe County, N.C. | 7,362,167 |

| Scott County, Va. | 6,859,172 |

| Tazewell County, Va. | 6,816,041 |

| Bell County, Ky. | 6,766,902 |

| Harlan County, Ky. | 6,722,624 |

| Dickenson County, Va. | 6,420,717 |

Source: ARC Funds by County, Joe Cerniglia, Appalachian Regional Commission, Washington, D.C.

With the exception of Buncombe and Whitfield Counties, the above list is composed of coal counties, none of which has a high proportion of National Forest land. It is noteworthy that Buncombe County, where Asheville is located, received a relatively large share of ARC funds, an indication that development efforts were often concentrated in areas with an exhibited potential for growth.

For the 12 Southern Appalachian counties selected for detailed analysis in this report, a total of $23,438,631 in ARC funds were spent from the Commission's beginning through March 25, 1980. The breakdown of these expenditures and the expenditures per capita are shown in table 14. The difference in expenditures on county projects between the selected group of counties with large areas of National Forests and the selected group with no National Forests is clear. The latter received more than four times as much ARC funds as the National-Forest counties, although the group had only about twice the population. For example, Bland County got no funds at all, and Graham got less than $500,000, while Hancock County, with about the same small population, got $1.3 million. Thus, in terms of ARC funds per capita provided at the county level, the counties without National Forests fared about twice as well.

Table 14.—Total and per capita funds allotted by Appalachian Regional Commission to 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties, 1980

| County and State |

Total ARC funds as of March 25, 1980 |

Population as of July 1, 1975 |

ARC funds per capita |

| High proportion of National Forest | |||

| Union, Ga. | $ 633,163 | 8,110 | $ 78,07 |

| Graham, N.C. | 481,700* | 6,641 | 72.53 |

| Macon, N.C. | 1,389,079 | 18,163 | 76,49 |

| Unicoi, Tenn. | 725,756 | 15,702 | 46.22 |

| McCreary, Ky. | 820,570 | 14,342 | 57.21 |

| Bland, Va. | none | 5,596 | none |

| Total | $ 4,050,268 | 68,554 | $ 59.08 |

| Little or no National Forest | |||

| Habersham, Ga. | $ 1,458,124 | 23,128 | $ 63.05 |

| Ashe, N.C. | 1,853,312 | 20,211 | 91.70 |

| Henderson, N.C. | 4,684,722 | 48,647 | 96.30 |

| Hancock, Tenn. | 1,353,806 | 6,486 | 208.73 |

| Knox, Ky. | 4,795,525 | 26,713 | 179.52 |

| Buchanan, Va. | 5,242,874 | 34,582 | 151.61 |

| Total | $19,388,363 | 159,767 | $121.35 |

1No funds allotted, 1973-80

Source: Appalachian Regional Commission data sheets, "Financial

information for all Projects by county." Courtesy of Joe Cerniglia,

ARC, Washington, D.C.

Of the 12 study counties, those that have received the most funds per capita are the predominantly coal counties—Hancock, Knox, and Buchanan. Here the funds have been spent diversely. The most costly ARC project in Hancock County was an access road between Morristown and Rogersville; Buchanan County received $2 million for construction of the Buchanan General Hospital; in Knox County, ARC funds were spent for an industrial park access road, the Union College Science Center building, and numerous smaller projects, ranging from an industrial park rail siding to an emergency radio communications network. Although such expenditures have probably contributed to the counties' wellbeing, they do not appear to have been aimed at the hard-cord victims of coal mining. (For all 12 study-area counties, about one-fifth of the total ARC funds were spent on roads and over one-quarter on vocational education.)

For the six counties with a high proportion of land in National Forests, McCreary and Graham are typical. Most of McCreary's $820,570 ARC funds went to the McCreary County High School vocational education department in 1974. In 1976, over $250,000 were spent on the McCreary County Park. Graham County's ARC funds also went largely for a vocational education facility, although a sewage treatment facility and solid waste disposal program were also funded. Graham County received no direct ARC funds between 1973 and 1980.

This assessment of the impact of both the ARC programs and the various anti-poverty programs initiated under OEO on the Southern Appalachians is neither clearcut nor exhaustive. However, an examination of changes in certain poverty indicators over time suggests that noticeable improvement has occurred. Table 15 presents changes from 1960 to 1970, 1975 or 1976 for the four poverty indicators shown earlier over the five Southern Appalachian States.

Table 15.—Changes in four poverty indicators for the Appalachian Mountain sections of five southern states, 1960-76

| Area | Per capita income as percentage of U.S. average |

Percentage of households below poverty level |

Infant mortality rate: deaths per thousand |

Percentage of persons aged 16-17 not enrolled in school | ||||

| 1965 | 1976 | 1960 | 1970 | 1960 | 1975 | 1960 | 1970 | |

| United States | 100 | 100 | 22.1 | 13.7 | 26.0 | 16.1 | 19.1 | 10.7 |

| Appalachian Kentucky | 49 | 68 | 58.4 | 38.8 | 30.9 | 17.1 | 33.0 | 25.3 |

| Appalachian Virginia | 55 | 75 | 24.4 | 0.4 | 31.0 | 21.6 | 33.1 | 17.5 |

| Appalachian Tennessee | 70 | 79 | 39.9 | 22.4 | 27.7 | 15.8 | 27.9 | 19.0 |

| Appalachia North Carolina | 75 | 84 | 37.2 | 18.8 | 26.8 | 19.1 | 25.6 | 17.1 |

| Appalachian Georgia | 70 | 77 | 38.5 | 16.9 | 29.1 | 16.4 | 28.0 | 25.3 |

Source: Compiled from Appalachia—A Reference Book, Appalachian Regional Commission, February 1979, pp. 56, 66, 74, and 77.

For all States, all indicators show an improvement over time, although in the 1970's the region still lagged behind much of the Nation. The most dramatic improvements in per capita income were for Appalachian Kentucky and Virginia—the poorest areas in 1960. Although they were still the poorest in 1976, per-capita income in those States was much closer to the regional average. Other noteworthy changes include an overall drop in the infant mortality rate closer to the national average (the Appalachian Tennessee rate was actually below national average), and a considerable decrease in the percent of families below poverty level. Although the number of persons 16-17 not enrolled in school decreased between 1960 and 1970, the percentage change was not as large as that for the Nation as a whole.

For the 12 study counties, changes in poverty indicators over the decade of the 1960's were typical of those across the Southern Appalachians, but appear greater for the counties with much area in National Forest than for those with little or no national forest land, as shown in table 16. In 1960, the six counties with a high proportion of national-forest land appeared to be poorer than their counterparts with little or no national-forest land; by 1970, there is a suggestion that the reverse was true.

Table 16—Changes in four poverty indicators for 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties, 1960-74

| High proportion of National Forest | Little or no National Forest | ||||||||||||||

| Union, Ga. | Graham, N.C. | Macon, N.C. | Unicoi, Tenn. | McCreary, Ky. | Bland, Va. | Six-County weighted average* | Habersham, Ga. | Ashe, N.C. | Henderson, N.C. | Hancock, Tenn. | Knox, Ky. | Buchanan, Va. | Six-County weighted average* | ||

| 768 | 770 | 870 | 1,127 | 481 | 836 | 809 | 1,104 | 759 | 1,355 | 516 | 594 | 844 | 862 | 1960> | Per capita income—$ |

| 2,853 | 2,880 | 2,922 | 3,165 | 1,915 | 2,977 | 2,785 | 3,256 | 2,816 | 3,814 | 1,827 | 2,278 | 3,496 | 2,915 | 1974 | |

| 67.1 | 58.0 | 56.2 | 39.6 | 71.5 | 56.2 | 58.1 | 35.5 | 60.9 | 35.5 | 78.0 | 70.5 | 50.2 | 55.1 | 1960 | Percentage of families below poverty level |

| 35.4 | 24.8 | 24.9 | 19.8 | 53.7 | 20.0 | 29.8 | 16.5 | 28.0 | 19.9 | 55.5 | 48.4 | 27.2 | 32.6 | 1969 | |

| 8.8 | 5.9 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 13.3 | <1.0 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 7.7 | 2.3 | 8.7 | 11.7 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 1960 | Percentage of population receiving public assistance |

| 4.8 | 1.0 | <1.0 | 4.1 | 8.4 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 8.5 | 9.9 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 1972 | |

| 10.2 | 7.6 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 11.8 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 4.0 | 8.8 | 1960 | Percentage of population 65 years or older |

| 13.7 | 12.4 | 17.0 | 12.5 | 10.3 | 11.2 | 12.9 | 10.2 | 13.5 | 16.1 | 12.8 | 11.7 | 6.4 | 11.8 | 1970 | |

*For percentage of families below poverty

level, averages are unweighted.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, County and City Data Book,

(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1967, 1972, and 1977).

Although the six counties without National Forests had a higher average per capita income in 1974, the difference between the two groups of counties analyzed had closed from 6 percent to 4 percent since 1960. Furthermore, by the end of the 1960's, the counties with little or no National Forest had a greater percentage of families below poverty level (a reverse of the situation in 1960) and a higher percentage of people receiving public assistance. Indeed, in Buchanan County, with no National Forest, although the population dropped from 36,724 to 32,071 between 1960 and 1970, the number of people receiving AFDC payments increased between 1964 and 1972 from 837 to 2,009. Again, the predominantly coal counties appeared the poorest counties in both groups, in spite of signs of relative improvement. McCreary, Knox, and Hancock Counties, in particular—one of which has over half its land in National Forest, the other two having little or none—ranked low according to all the poverty indices. All 12 study counties experienced a uniform increase in the proportion aged 65 or older. Such a change suggests a continued trend in the outmigration of the younger population and, for some counties, an inmigration of persons of retirement age.

Table 17 summarizes changes in net migration rates from the 12 study counties from 1960 to 1975. The data indicate that between 1960 and 1970, although the rate had slowed from the previous decade, net outmigration from most of the counties was still considerable. The coal counties of Buchanan, Hancock, Knox, and McCreary continued to experience the greatest outmigration losses, with Bland and Graham Counties close behind.

Table 17.—Changes in net migration for 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties, 1960-70 and 1970-75

| Percentage change |

High proportion of National Forest | Little or no National Forest | ||||||||||

| Union | Graham | Macon | Unicoi | McCreary | Bland | Habersham | Ashe | Henderson | Hancock | Knox | Buchanan | |

| 1960-70 | -4.2 | -11.8 | -0.3 | -7.9 | -13.3 | 13.2 | 2.2 | -9.9 | 9.4 | -21.4 | -16.7 | -30.2 |

| 1970-75 | 13.9 | -4.4 | 14.0 | -0.4 | 9.7 | 0.1 | 7.5 | 0.5 | 12.5 | -5.4 | 6.6 | -1.6 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, County and City Data Book (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1967, 1972, and 1977).

Between 1970 and 1975, however, all 12 experienced a marked change. In several, net losses changed to net gains; at the very least, the rate of net outmigration dropped. Changes were most dramatic for the coal counties of Buchanan (29 points), Knox (22 points), and McCreary (23 points), although Union, Hancock, and Macon Counties improved by from 14 to 18 percentage points. The magnitude of the migration changes was apparently not related to the proportion of National Forest land. These population shifts will be discussed further in chapter VIII.

New Forest Is Created In Kentucky

One of the major concerns of the President's Appalachian Regional Commission (PARC), created by President Kennedy in 1963, was the development of the timber resource of the Appalachian region. "The timber resource," PARC reviewers felt, "should provide much of the foundation for the renewed economic vigor of the region." [43] However, fragmented ownership proved to be one of the region's most serious timber problems, and "substantial acreages of forest land" in Appalachia were found so depleted as "not likely to be rehabilitated and adequately protected under private ownership." [44] Thus, public ownership of such lands was recommended so that they could be returned to full productivity.

Following the recommendations of Senator Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia and Governor Bert T. Combs of Kentucky, two mountain areas—one bordering the Monongahela National Forest, the other in eastern Kentucky—were studied for National Forest expansion in Appalachia. The area of eastern Kentucky was of about 4 million acres encompassing headwaters of the Cumberland, Kentucky, Licking, and Big Sandy Rivers. PARC recommended acquiring about 1.3 million acres over a 10-year period—not only to meet timber development recommendations but also to further general goals of the President's Commission. [45]

Two years later, PARC's recommendations were realized. In February 1965, Congress created the Redbird Purchase Unit encompassing acreage in Leslie, Clay, Bell, Harlan, Owsley, Perry, and Knox Counties. Land acquisition began almost immediately. In April 1966, Congress renamed the Cumberland National Forest the Daniel Boone National Forest.

As in other parts of the Southern Appalachians before Forest Service acquisition, lands of the Redbird Purchase Unit had been held largely by absentee timber corporations, landholding companies, and mining interests since 1900 or earlier. As such, they had been extensively cut over and mined. [46] Indeed, the Redbird contained some of the most abused land of the whole region. For the most part it was abandoned, and the few residents remaining, either small landholders or tenants, lived in the worst conditions of Appalachian poverty.

The Forest Service had considered this area several times as potential National Forest. Forest examiners had gone to eastern Kentucky in the first years after the passage of the Weeks Act. The area was reexamined during the 1920's, and again in the 1930's. By then, most of the lands had been heavily cut over, and could provide only the most meager existence for the inhabitants. In 1933 Mary Breckenridge, founder of the Frontier Nursing Service in eastern Kentucky, went before the National Forest Reservation Commission to plead for a National Forest in the area. A National Forest, she felt, was the logical land-management choice for the region, not only to preserve and develop the timber resource and provide local employment, but also to prevent disastrous downstream flooding. [47]

Although Mary Breckenridge was well received, and although Forest Service examiners visited the area and expressed strong interest in acquisition, no purchase unit was established. The major reason then, as it was in 1914, was that most of the land was held by timber coal companies whose owners either were unwilling to sell at all or refused to relinquish mining rights to the land until the coal was depleted. [48]

In the 1960's, since much of the land had not only been logged but also mined, the Forest Service was more successful with acquisition. The first tract purchased in the Redbird Unit was of about 60,000 acres from the Red Bird Timber Co. The land, located in Clay, Leslie, Harlan, and Bell Counties, formed the nucleus of the almost 300,000-acre unit. Red Bird Timber had bought the tract from Fordson Coal Co., a Ford Motor Co. subsidiary, in the early 1960's; Fordson had held the land for almost 40 years after buying it from Peabody Coal in 1923. [49]

Although some coal and timber companies were willing to sell to the Forest Service, the unit was not hailed enthusiastically by all of the local population. Indeed, for several weeks running, the Leslie County News lamented the Federal takeover and scorned the benefits that were assured the area. Although acknowledging that Government ownership could improve the land measurably, the paper said that Federal ownership is bad because it irrevocably takes the land away from private ownership. "It is a fact," stated The Politician of the paper, "that once the government does purchase property, it rarely sells it back."

A democracy does have many problems, but government ownership is not a cure all. Nor can it automatically make profitable a venture which has failed, in hands of individuals. The only real difference is that the government can afford to operate anything, anywhere, anytime, because it doesn't have to make a profit. It doesn't have anything invested, except the taxpayers' money. [50]

Certainly, there was not much illusion that land acquisition for the Redbird would directly benefit the local population. As L. E. Perry of McCreary County wrote:

The land acquisition program was expanded into the Appalachia poverty areas, presumably to bring relief to the destitute people of Clay, Leslie and Bell Counties. In reality the drive was for more land area where the corporations and land holding companies needed to unload their cut-over timberlands at a good profit while retaining the rich mineral deposits. It is yet [in 1980] to be determined how the poverty stricken people of the area were helped by this land buying program. [51]

With the purchase of the Red Bird Timber Co. tract, the Forest Service assumed responsibility not only for the land, but also for 115 families who had been tenants of the company on a year-to-year basis. Most of these families lived in substandard housing on remote, unmaintained roads; about 30 percent were estimated to have been receiving welfare payments. The appearance of the mountaineers' homes was dismal; trash and refuse littered the yards; the exteriors of the homes were delapidated. [52]

When the families learned of Forest Service acquisition of their leased land, they raised many questions about the continuity or improvement of their lives. The policy was that, although no one would be forcibly removed from his home, the eventual goal was to relocate all the families. Special-use permits would be issued for continued tenancy and farming, but the Forest Service would not maintain the roads serving the homes and would require "that the permittees clean up the premises and keep them clean." So its policy differed little from that of the Red Bird Corp., except for cleanliness. Here, the Forest Service was "reluctant to condone or continue a practice [freely dumping trash in the yards and in the woods] which is perpetuating a situation which appears to be deplorable." [53]

Throughout the next decade, rangers on the Redbird Unit had continuous problems with some of the inhabitants, such as special-use permits, trash disposal, and incendiary fires. Maintaining a firm but friendly attitude was difficult, even for the most resourceful ranger.

For example, the first ranger on the Redbird Unit tells of his experiences with one particularly stubborn tenant family which had occupied several acres in the Redbird since the days of Fordson Coal Co. Although a tenant of Fordson, the family had persistently filed claims for the property they were occupying, but could never prove their case to obtain a bona fide deed.

When the Government acquired the lands the family was occupying, the second generation of tenants was not content with a special-use permit and continued the fight to own their small tract. They threatened the district ranger with bodily harm, and went so far as to begin construction of building foundations on the tract they occupied. In short, they "interfered with national forest management." Ultimately, the case was settled in Federal court and the family was required to leave the National Forest. Several family members, however, continued for at least 10 years to assert their claim to the land. [54]

|

| Figure 105.—Severely cutover, farmed-out steep slope along dirt road at headwaters of Elk Creek, Clay County, typical of the Redbird Purchase Unit in eastern Kentucky in 1965. The Redbird, which comprises the headwaters of the Kentucky and Cumberland rivers in seven southeastern coal counties, is the Forest Service's most recent Purchase Unit. Note dilapidated houses, abandoned auto. This scene was then typical of this area. Recent strong demand for coal has relieved the depression situation somewhat. (Forest Service photo F-512677) |

Weeks Act Purchases Rise Steadily

After the lean years of the Eisenhower Administration, appropriations for Weeks Act purchases increased almost steadily from 1961 until 1967, from $100,000 to $2,480,000. In 1966, more acres were approved for Weeks Act acquisition than had been approved for all the previous 11 years together. [55] Throughout the late 1960's and early 1970's, acquisition in the Redbird Purchase Unit dominated the business of the National Forest Reservation Commission. According to NFRC minutes in 1972, "during the past six years, over one-half of the Weeks Law funds have been concentrated in the Redbird Purchase Unit." [56]

In 1972, the National Forest Reservation Commission approved a 96,061-acre extension to the Redbird Purchase Unit. The extension included land in Owsley and Perry Counties that was "forested although heavily cutover." The Commission felt that Federal acquisition would help protect the area's watersheds and improve the water quality of an existing reservoir in the region. It was projected that acquisition costs would range between $25 and $80 per acre, and that the purchase program would run for about 20. [57] In 1975, the Redbird was still identified as the "major thrust area" for NFRC land purchase. [58]

Most of the tracts purchased in the Redbird were small, ranging between 10 and 300 acres. Larger tracts were the exception, although in 1973 over 9,000 acres were acquired from the Mayne Land and Development Co. [59] From its creation in 1965 until 1978, an average of about 7,500 acres was acquired in the Redbird each year. In 1977 the net acreage of the purchase unit was almost 135,000 acres, In 1981 it was just over 140,000. Prices for land in the Redbird have been far below those in the other Southern Appalachian National Forests. In fiscal year 1977, for example, tracts acquired in the Redbird averaged $85.97 per acre; those in the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests averaged $441.27 per acre, and those in the Cherokee, $635.22 per acre. [60]

Serious Problem With Mineral Rights

The problem of mineral rights on the lands of eastern Kentucky, which halted efforts to establish a National Forest there 60 years ago, has plagued the Forest Service since the Redbird was established in 1966. Much of the land in the Redbird is covered by the Kentucky broad form deed, which allows strip-mining and gives the deed holder wide freedom with the land. At first the National Forest Reservation Commission was reluctant to purchase lands that had mineral rights outstanding in a third party with a Broad Form Deed. Gradually, however, it was recognized that so much Redbird land was of this type, some would have to be acquired to create a manageable National Forest district.

Thus, many tracts in eastern Kentucky have been purchased with mineral rights held by third parties. The Commission consoled itself with the expectation that, because Kentucky had strengthened its 1954 strip-mining law, the mining would be acceptable. [61] Mineral rights have been separately purchased, where possible, however, to facilitate Forest Service control. For example, in 1971 the National Forest Reservation Commission authorized $10 per acre to purchase the mineral rights to the Fordson Coal Co. lands. [62] Ultimately, of course, the Commission could obtain the mineral rights with the Secretary's condemnation, an option that was entertained more frequently in the 1970's as recreation and wilderness forces collided with mining interests on the Daniel Boone.

|

| Figure 106.—Hillsides scarred by strip and auger coal mining along Beech Fork, Leslie County, Ky., in 1965. A common sight then in Redbird Purchase Unit. Acid soil debris leached down to pollute streams and kill fish for many years. New highway and old road cut slope at lower levels. (Forest Service photo F-512684) |

New Law Boosts Recreational Land Purchases

Although land acquisition in the Southern Appalachians during the 1960's and 1970's was concentrated in the Redbird Unit, the other National Forests in the region also expanded because of a boost in acquisition monies provided by the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). The Fund, established by the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of September 1964, was a direct outgrowth of the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC) study. [63] The main purpose of the Act was to enhance the recreational resources of America through planning, acquisition of lands, and recreational development. A separate fund was established to provide money to individual State and local governments on a matching basis and to Federal agencies to carry out the purposes of the Act. Monies were available, through the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (later to become the Heritage, Conservation, and Recreation Service), for the Forest Service to acquire private inholdings in wilderness areas, lands for outdoor recreation purposes, or areas where any fish or wildlife species was threatened. The Act stipulated that no more than 15 percent of the acreage so acquired could be west of the 100th meridian.

After 1965, LWCF appropriations became by far the chief source of money for National Forest land acquisitions. Between 1965 and 1977 an average of over $25 million per year was provided for National Forest acquisition from the fund. [64] By the end of 1973, 35 percent of the National Forest acres acquired through the LWCF were in Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee. [65] In fiscal year 1976 conservation fund monies exceeded Weeks Act monies by a ratio of more than 25 to 1. [66] Increasingly, the Fund was used to purchase lands on the older Southern Appalachian National Forests with high recreational value, while Weeks Act appropriations were devoted to the Redbird Unit. [67] Table 18 summarizes the LWCF funds spent for land acquisitions in the Southern Appalachian National Forests during the first 14 years of the Fund, ending June 30, 1980.

Table 18.—Total lands acquired with Land and Water Conservation Act funds in National Forests of the Southern Appalachians, 1966-80

| Forest | State | LWCF acquisition funds* |

| Chattahoochee | Georgia | $ 7,898,000 |

| Daniel Boone | Kentucky | 1,622,000 |

| Nantahala | North Carolina | 10,139,000 |

| Pisgah | North Carolina | 4,923,000 |

| Cherokee | Tennessee | 4,046,000 |

| Jefferson | Virginia | 16,106,000 |

| Total | $44,734,000 | |

*Rounded to nearest thousand. Fiscal year data.

Source: Data on National Forest lands acquired through LWCF monies:

Heritage, Conservation, and Recreation Service, Department of the Interior,

Washington, D.C.

Although land acquisition for National Forests in the Southern Appalachians continued throughout the 1960's and 1970's, large purchases were generally not made without a clear indication that they were approved by the local public. A case in point is a 46,000-acre tract largely in Bland County, Va., owned by Consolidation Coal Co., a subsidiary of Continental Oil Co. It was considered by the Commission in January 1972. Because the tract amounted to about one-fifth the land area of Bland County, the NFRC felt that evidence of public support for the purchase was necessary. [68]

The tract in question had been logged about 40 years before and contained only "a residual stand of poor quality timber." Manganese strip-mining had also occurred on the land, leaving behind a few small lakes. The tract was not being used for farming or grazing; it was mountain land with no ongoing commercial utility except some small-scale lumbering. However, its recreational potential was considered "great." [69]

Although the Virginia Commission for Outdoor Recreation favored Forest Service purchase, Bland County was divided on the issue. One-half of the letters to the Forest Service from local groups and individuals approved of the purchase, and the Bland County Board of Supervisors was split, two to two, on the acquisition. The opponents did not want to see the land removed from the tax rolls. The estimated loss of revenue from such removal was an annual $3,000, without considering timber harvesting. Although the tract contained poor second-growth timber, the Forest Service claimed it was suitable for immediate pulpwood harvesting, which would bring additional revenues. The NFRC recommended that the Bland County purchase be approved. [70] The area actually so acquired was about 40,000 acres.

|

| Figure 107.—Strip coal mine spoil banks, partly reforested by planting, along Little Goose Creek in Leslie County, Ky., in 1965. At that time, more than 1,500 acres of strip mine tailings in the area were still in need of rehabilitation and revegetation. (Forest Service photo F-512685) |

Forest Commission Dissolved

Throughout the 1960's and early 1970's, the National Forest Reservation Commission was finding it nearly impossible to assemble the various cabinet members, senators, and congressmen, or even a quorum of their deputies, at the same time to consider National Forest land acquisitions. Approval was usually granted in "unassembled" meetings. Finally, in October 1976, the NFRC was dissolved. The National Forest Management Act of 1976 transferred its functions to the Secretary of Agriculture, [71] granting him authority to approve small, routine acquisitions, but requiring those of $25,000 or more to be submitted to the House Agriculture Committee and the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry for a 30-day review.

The demise of NFRC marked a symbolic end of National Forest creation under the Weeks Act. After the Redbird Purchase Unit was added to Daniel Boone National Forest, acquisition of large cutover tracts at major stream headwaters virtually stopped. By 1975 most such lands in eastern watersheds not in Federal ownership were too expensive to buy or not for sale. Additions to eastern National Forests were thus increasingly based on other legal authority, and primarily for recreation—as will be discussed in chapter VIII.

Recent National Forest Timber Management

Although the demand for timber slackened in the immediate postwar years, the 1950's saw a steady rise in timber harvesting across the Nation as housing construction and timber exports increased. In 1952 the Forest Service, in cooperation with other Federal, State, and private agencies, began a new inventory and assessment of the country's timber resource known as the Timber Resource Review (TRR). The TRR report, published in final revised form in 1958, found that in 1952 growth of sawtimber was almost equal to the cut, and in the South and East, exceeded the cut. However, the report expressed serious concern over the ability of the nation's forests to meet future timber demands, which were projected to rise rapidly. Although the TRR report fell short of recommending regulation of harvesting procedures on private timberlands, it emphasized the need for increased National Forest production and more intensive timber management on lands of all ownerships. [72]

At the same time, as discussed in chapter VI, pressures on the National Forests had been building for expanded outdoor recreational opportunities. In June 1958, shortly after the publication of the TRR report, President Eisenhower established the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC) to inventory the nation's recreational resources. (ORRRC is discussed further in chapter VIII.) Meanwhile, the Forest Service was handling a multitude of problems connected with livestock grazing in the Western National Forests and was receiving increasing numbers of requests for special uses of Federal land, including the reservation of more wilderness. The combined pressures on the National Forests throughout the 1950's led to the drafting and eventual passage of the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, which defined the purposes for which National Forests were established and administered, [73] mostly reaffirming long-standing Forest Service policies and practices. It was the organization's feeling that the Forest Service "had better get its national forest house in order" that prompted the legislation. [74]

|

| Figure 108.—Open mine of Manganese Mining & Contracting Company on Glade Mountain near Marion, Smyth County, Va., in Holston Ranger District of Jefferson National Forest, in July 1955. The firm operated under a Forest Service special-use permit, and maintained a settling pond to collect mine waste to avoid polluting streams. Mineral rights had been reserved on these lands when the land was sold to the Federal Government. (Forest Service photo F-479124) |

The Multiple Use Act of 1960

The Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, enacted on June 12, 1960, stated five renewable resources or uses of the National Forests in alphabetical order: outdoor recreation, range (grazing of domestic livestock), timber, watershed, and wildlife and fish. (Mining was not mentioned; it is not a renewable use, and was not at the time felt to be in need of express encouragement.) In essence, the Act declared that National Forests do not exist for any single purpose and implied that no one resource should be overemphasized at the expense of others. The Multiple-Use Sustained Yield Act articulated the management ideals that the Forest Service had espoused for years: the National Forests are to be managed for a variety of purposes, with an effort to sustain the benefits of each purpose for the longest possible period of time. Although conflicts between purposes (uses) are possible, they are to be resolved in favor of the long-term public interest—in Pinchot's paraphrase, "The greatest good of the greatest number in the long run."

Much has been written about the ambiguities inherent in the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, [75] First, the Act states that the five purposes are "supplemental to but not in derogation of" the purposes stated in the so-called Organic Administration Act of 1897 that provided for management of the forest reserves. Those purposes were forest improvement and protection, securing favorable water flows, and a continuous timber supply. The Act also specifically protected prospecting and mining rights. There is some overlap between the two acts, and whether the more limited purposes stated in the 1897 Act should take precedence over those of the 1960 Act was publicly discussed after the latter's enactment. [76] Resolution of competing claims remained difficult. The more recent laws of the 1970's have clarified the situation substantially.

In addition, the 1960 Act's definition of multiple use was vague and simplistic. The criteria of flexibility in uses over time and continuous resource productivity can give "the unwary or ill-informed . . . the comforting illusion that if the uses are multiple enough there will be sufficient for everyone." [77] Moreover, the Act gives little specific direction as to how National Forests are actually to be managed, much less just how conflicts among purposes are to be resolved. Thus, some critics have charged that the multiple-use concept is a "facade behind which the Forest Service can operate to make decisions according to the relative strengths of clientele groups in a given area at a given time," or that it is a "blank check" to manage the National Forests as it sees fit. [78]

Certainly, the legislation was not so much a management tool as it was a statement allowing the Forest Service management flexibility while placating the multiple forest users. As Edward C. Crafts, Assistant Chief of the Forest Service during the 1950's, wrote:

. . . there was a chance the various pressure groups might tend to offset each other to some degree. For example, the grazing people might like the bill because their interests would be equated with timber and recreation. Recreation and wilderness users should like it because it would raise them to a status equal to commercial users. The timber industry which had enjoyed preferential treatment would not like losing this preference, but on the other hand would be protected against being overridden roughshod by the recreation and wilderness enthusiasts. The bill contained a little something for everyone. [79]

Nevertheless, in spite of its ambiguity and openness to conflicting interpretation, the Act did express the fundamental approach of Congress and the Forest Service to managing lands under pressure from multiple interest groups and fast growing U.S. population: a recognition of all the uses to which forests can be put (except mining), and an attempt to diversify land use—or prevent single use—wherever possible. As Richard E. McArdle, then Forest Service Chief, stated at the Fifth World Forestry Congress in August 1960, "in most instances forest land is not fully serving the people if used exclusively for a purpose which could also be achieved in combination with several other uses." [80] McArdle conceded that multiple use is not "a panacea," but he pointed out that because it helps considerably to overcome problems of scarcity and resolve conflicts of interest, it is the "best management for most of the publicly owned forest lands of the United States." [81]

Difficult to Promote Private Forestry

Against the background of potentially conflicting management directives inherent in the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, Forest Service management of the Southern Appalachian forests became increasingly complex through the 1960's. The complexity was compounded by the development initiatives encouraged by the President's Appalachian Regional Commission. In 1963 PARC recommended that a timber resource development program for the whole Appalachian region be launched "on a scale far greater than ever before." [82] This program would involve an accelerated effort on both National Forests and on State and private lands. Specifically recommended initiatives were reforestation, timber stand improvement, construction of access roads, and the location and marking of property boundaries, as well as firebreak construction and erosion control. PARC estimated that more than 37,000 man-years of employment would be involved in the initial 5 year effort, and that more than $240 million should be spent. [83]

The Appalachian Regional Development Act of 1965 creating the new Commission with expanded powers made a specific provision for technical assistance to be given for the organization and operation of private "timber development organizations." Timber development organizations were conceived as nonprofit corporations that would manage the timber resources of participating private landowners. One of the first research reports prepared for ARC was an evaluation of such organizations as a source of regional economic benefits.

The report concluded that, because sawmilling dominated the timbering industry of Appalachia—not pulpwood, plywood, or the like—and because of "restrictions imposed by timber availability, timber procurement economics, and requirements for timber quality," the industry was not expected to grow. [84] Furthermore, private forest lands were found to be in "multiple thousands of small size holdings," and many of the region's timber owners unmotivated to improve their long-term productivity. "Feelings of disinterest and mistrust" often characterized sales transactions, as well as "a propensity toward overengagement in dickering and negotiation." For these reasons, consolidating private timber holdings and turning their management over to second parties did not seem feasible, and timber development organizations were proclaimed "not.., viable in sufficient numbers to yield substantial economic benefits to Appalachia." [85]

This finding serves to emphasize the stabilizing role of Federal land managed for a variety of uses in the development of the Appalachian timber resource. Clearly, the National Forests did not exhibit the fragmented ownership, lack of owner motivation, and poor resource quality that characterized the private timber industry. Nevertheless, because of their timber composition, Southern Appalachian forests could not then be managed in the same way that Pacific forests and Southern coastal forests were. Appalachian forests did not at that time contain nearly the proportion of commercial timber acreage that the Western and the Southern piedmont and coastal forests did. Much was low-quality, second-growth hardwood, the product of a history of repeated "selective" cuttings, actually destructive "high-grading" in most cases, that left behind the undesirable and damaged individuals and species. Further, the quality hardwood that was present had a fairly long rotation cycle: between 40 and 80 years for sawtimber-sized trees. [86]