|

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81 |

|

Chapter VIII

Recreational Development of the Southern Appalachians: 1960-81

The recreational development of the Southern Appalachian Mountains during the 1960's and 1970's was extensive. It brought widespread changes in landownership patterns, greater visitation and use of the region's forests, and a vocal, organized, and critical response from the Southern Appalachian mountaineer. After 1965 the Federal Government provided millions of dollars from the Land and Water Conservation Fund to acquire private lands. Then a series of Federal laws established National Recreation Areas, Wild and Scenic Rivers, a National Trail, and finally confirmed and extended wilderness areas in the region's National Forests. At the same time, second-home builders and resort developers helped increase the pattern of absentee landownership already typical of the region. In response to the accelerating loss of private and locally held land and local land-use control, residents throughout the mountains organized to protest. The people of the Southern Appalachians now seemed much more determined to resist giving up ownership of land than they had been in the past.

As discussed in chapter VI, outdoor recreation became more and more a national pursuit and a national concern after World War II, as the spendable income, leisure time, and mobility of Americans increased rapidly. Concern with the Nation's ability to satisfy recreational demands was expressed in Federal legislation in June 1958, when President Eisenhower created the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC). [1] The Commission's task was to inventory and evaluate America's outdoor recreational resources, both current and future, and to provide comprehensive information and recommendations so that the necessary quality and quantity of resources could be assured to all. It was composed of four senators, four congressmen, and seven private citizens.

The Commission's immense report was issued in 1961, in 27 volumes. In essence, it found that America's recreational needs were not being effectively met, and that since future demands would accelerate, money and further study were needed at the Federal, State, and local levels. The Commission provided more than 50 specific recommendations, which can be grouped into five general categories. These were: (1) the establishment of a national outdoor recreation policy, (2) guidelines for the management of outdoor recreation, (3) increased acquisition of recreational lands and development of recreational facilities, (4) a grants-in-aid program to the States for recreational development, and (5) the establishment of a (Federal) Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. [2]

Bureau of Outdoor Recreation Is

Created

During the next 10 years, virtually all the ORRRC recommendations were enacted. In April 1962 the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (BOR) was established in the Department of the Interior. [3] Edward C. Crafts, former Assistant Chief of the Forest Service, became its first Director. The Bureau's purpose was to coordinate the recreational activities of the Federal Government under a multitude of agencies and to provide guidance to the States in planning and funding recreational development. At the same time a policymaking Recreation Advisory Council was established by executive order. It was composed of the Secretaries of the Interior, Agriculture, Defense, and Health, Education and Welfare, and the Administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency. [4] The Outdoor Recreation Act of 1963 was passed to expedite coordination of recreational planning by Federal agencies and initiate a comprehensive national recreation plan. [5] A year later, the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act was passed to provide funds for Federal and State recreational development.

This heavy Federal legislative and administrative emphasis on outdoor recreation was to have a decided impact on the Southern Appalachians during the 1960's and 1970's. Many of the Federal recreation programs and dollars spent on recreation were channeled into the region. The number of annual visitors to the southern mountain forests rose substantially, as increased recreational development—both public and private—increased tourist attractions and investment possibilities. In addition, the renewal of Federal funding for recreation made land acquisition appear much more urgent than it had previously been for general National Forest purposes. Consequently, the Forest Service decided to exercise its condemnation power as a final option, if needed, to acquire especially worthy sites from owners unwilling to sell. Such condemnation aroused residents in several areas, many of whom organized for the first time in often bitter protest of Federal land acquisition policies.

Since the early 1900's, with the genesis of the movements for National Parks in the Great Smoky and Blue Ridge Mountains and for the Blue Ridge Parkway, the recreational potential of the region's natural resources had been well recognized. By 1960, decades of Federal land acquisition throughout the region had put together very large tracts close to the Eastern Seaboard that appeared ripe for recreational development.

Studies conducted for the Appalachian Regional Commission were somewhat contradictory. One made for ARC by the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in 1966-67 declared the Southern Appalachian region had great potential to provide for rapidly rising demands for public recreation. The study, in estimating demand for outdoor recreation from 373 counties and parts of 53 Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas within 125 miles of Appalachia, calculated that to meet 1967 needs, at least 600,000 more acres were required for boating, 20,000 acres for camping, and 30,000 for picknicking. By the year 2000, it predicted, the recreational demands placed on the region would be "staggering"; thus, an intensive effort was believed necessary to provide recreational supplies to meet the demands. However, another study, made jointly by two private firms less than a year earlier for ARC, had warned against major public investment. [6]

The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), established in September 1964, was the principal Federal step taken to meet these perceived recreational demands. [7] The Fund, administered by the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, could be used for Federal acquisition of lands and waters—or interests in lands and waters such as scenic easements. The properties would be used to create National Recreation Areas in the National Parks and in the National Forests and to purchase private inholdings in the National Forests "primarily of value for outdoor recreation purposes" including wilderness. [8] The ORRRC report had stressed the need to rectify the imbalance between the abundance of Federal recreation lands in the West and their scarcity in the East. The Land and Water Conservation Fund was to address the need. [9] Within the Southern Appalachian forests, LWCF monies were used in the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area in southwestern Virginia, the Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and the Appalachian Trail. The Mount Rogers NRA was perhaps the most visible and most controversial use of LWCF funds in the region.

National Recreation Areas (NRA's) were first conceived and established by the President's Recreation Advisory Council. The first NRA's created in 1963, were administered by the National Park Service, and were principally based on a large reservoir, such as Lake Mead above Hoover (Boulder) Dam on the lower Colorado River. NRA's were defined to be spacious areas of not less than 20,000 acres, designed to achieve a high recreational carrying capacity, located within 250 miles of urban population centers. Each was to be established by an individual act of Congress. [10] The first National Recreation Area in the Appalachians was the Spruce Knob-Seneca Rocks NRA, established in September 1965 in the Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia. The Mount Rogers NRA, centered on Whitetop Mountain and Mount Rogers—the highest point in Virginia—was established in the Jefferson National Forest on May 31, 1966. [11]

|

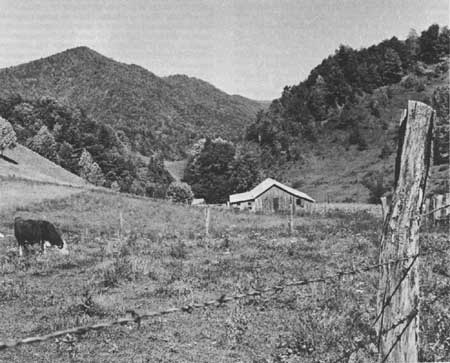

| Figure 111.—Hereford cattle grazing in mountain pasture adjoining Jefferson National Forest near Taylors Valley, Washington County. Va., between Damascus and Konnarock, close to the Tennessee State line and the present Mt. Rogers National Recreation Area administered by the Forest Service, in November 1966. White pine and northern hardwoods are visible on nearby slopes and ridges. (Forest Service photo F-515652) |

Mount Rogers National Recreation

Area

The Mount Rogers NRA was originally conceived as an intensely developed recreational complex of 150,000 acres with a 63-mile scenic highway, campgrounds, and nearby reservoirs. (Two of these reservoirs were part of the proposed Blue Ridge Project on the New River, to be discussed later.) Mount Rogers was expected not only to help satisfy future regional demands for outdoor recreation, but also to provide an economic boost to the economy of southwestern Virginia. As the Secretary of Agriculture stated in congressional testimony on the NRA:

The counties involved [in the NRA] are in areas of continued and substantial unemployment and a relatively low rate of economic activity. A national recreation area will benefit this situation both immediately and in the long run through the inflow of funds and accelerated development and intensified administration and the upbuilding of a permanent economic base oriented to full utilization of all the national forest resources. [12]

However, the scope and intensity of development originally planned for Mount Rogers were not realized. The Forest Service finally shifted its priorities away from encouraging more motorized recreation such as those activities enabled by reservoirs and scenic highways, to more active, "dispersed" recreation, such as canoeing and backpacking [13] This shift is reflected in recreational use data by type of activity for two representative Southern Appalachian forests, the Cherokee in eastern Tennessee and the Chattahoochee in northern Georgia. For both forests between 1968 and 1980, automobile traveling declined somewhat, not in volume but as a percentage of all recreational activities. In the Cherokee, the decline was from 18 percent to 15 percent; in the Chattahoochee, it was from 22 to 19 percent. On the other hand, hiking more than doubled as a percentage of all recreational activities: in the Cherokee from 2.4 to 8 percent, in the Chattahoochee, from 4 to 8.9 percent. [14]

The legislation establishing the Mount Rogers NRA provided for acquisition of such lands, waters, or interests in them, by purchase, donation, exchange, transfer, or condemnation, as the Secretary of Agriculture deemed "needed or desirable." [15] The Land and Water Conservation Fund was to be used as the source of acquisition monies. The final Forest Service-developed plan for the NRA called for Federal ownership of 123,500 acres within the approximately 154,000-acre NRA boundary. By 1966 much of the desired acreage had already been acquired; some 58,000 acres were deemed "needed or desirable" to complete the future NRA. [16]

The defined "need" was based on the premise of protection, as the Secretary of Agriculture explained to Congress:

To fully develop and assure maximum public use and enjoyment of all the resources of this area, there will need to be come consolidation of landownership. The present ownership pattern, particularly in the immediate vicinity of Mount Rogers, precludes effective development for public use. Acquisition of intermingled private forest and meadowlands and of needed access and rights-of-way is essential to fully develop the outdoor recreation potential by protecting the outstanding scenic, botanical, and recreational qualities of the area . . . [17]

Of the approximately 58,000 desired acres remaining in private lands, the Forest Service estimated acquiring about 32,000 "during the next several years." Of the other 26,000, it was hoped that scenic easements could be used for a good portion, although the exact amount of land to be acquired or easements obtained could not be estimated. However, no scenic easements were obtained during the next 15 years. At the end of 1981 the first easement was acquired, 20 acres along a road in the Brushy Creek area, and another easement on a similar small tract was in the process of being acquired. The new plan for the NRA places strong emphasis upon scenic easements. [18]

Between 1967 and early 1981, approximately 25,000 more acres in 312 separate transactions were acquired for the Mount Rogers NRA. The lands selected for acquisition were generally in stream and river valleys where developed recreation facilities (campgrounds, roads, trails, parking, and picnic areas) could be located, and where the Forest Service generally had not previously acquired land. The acquisition process proceeded gradually over a 15-year period, dependent upon the funds available for purchase (mostly from the Land and Water Conservation Fund) and the operational plans of the Forest Service staff, and influenced by the local peoples' reactions to such acquisition. [19]

Of the 312 tracts, 51, totaling about 7,100 acres, were taken for the NRA through condemnation, Of these 51 tracts, 20 had full-time residents, 15 of whom did not want to sell at all. (Five agreed to sell, but wanted more money than the Forest Service offered.) The majority of the condemnation cases were filed between 1972 and 1975, in preparation for specific development projects. Most tracts were in western Grayson County, in the area of Pine Mountain, where a ski resort was planned under special use permit, and Fairwood Valley, where resort accommodations and camping facilities were planned. The Forest Service acquired the Pine Mountain lands to keep the area free from extraneous commercial development and thus maintain a natural camp setting. Resort to condemnation was minimized by Public Law 91-646 (1970) which liberalized relocation assistance benefits to displaced landowners who were living on their properties. However, some still resisted. [20] Many residents of the Mount Rogers area were angry and puzzled by the rationale for the taking of land. A newsletter of a local protest group declared:

Nowhere has the Forest Service lost more credibility and generated more ill will than in its land condemnation and acquisition practices. Everyone in the affected area has either lost land or had friends or relatives who did. These are people who ancestral homes are here, whose parents, grandparents, great and great-great-grandparents have lived here, and until recently were coerced into selling their land at a fraction of its worth.

The Forest Service has been condeming land for years, making sweeps through the area taking thousands of acres at a time while assuring residents "that's all the land we're going to buy." A few months later they sweep through again enlarging their borders. [21]

As a result of their disgruntlement, local citizens organized to combat the tentative Forest Service development plans. The Citizens for Southwest Virginia, which formed shortly after the Forest Service issued the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the NRA in spring 1978, was composed of citizens from the five-county area affected. They formed a Board of Directors of prominent citizens whose families had been in the area for generations. The organization claimed in 1978 that almost 10 percent of the five-county population had signed their petition of protest against further NRA development. [22]

Largely as a result of local citizen protest, supplemented by that of environmental groups nationwide, the Forest Service modified some of its initial development plans for Mount Rogers. The proposals for a scenic highway and for a ski resort were dropped completely. Projections that reservoirs would be constructed, that an excursion rail line would be built, that local investment capital would supplement Federal development proved too optimistic. The regional reservoirs and rail line were never built; the Mount Rogers Citizens Development Corporation, created to raise capital for local development use, failed to achieve its funding-raising goals. Regional economic conditions, however, began to improve without such massive development efforts.

The popular mandate, the Forest Service concluded, was clearly for dispersed recreation at Mount Rogers, with emphasis on hiking, camping, canoeing, and the like. [23]

In 1981 some members of the Citizens for Southwest Virginia were still active. Although in general they were satisfied with the modified development plans for the NRA, they were skeptical about a Forest Service "access road" being built between Troutdale and Damascus on the path of the supposedly defunct Scenic Highway. Citizens were still uneasy about Forest Service acquisition techniques, convinced that local landholders were sometimes intimidated through harassment and a lack of knowledge of their rights. [24] By 1981, the Citizens for Southwest Virginia had joined the National Inholders Association, a California-based organization created in early 1979 to change Federal land acquisition policies nationwide. [25]

|

| Figure 112.—Visitors listening to forest interpreter on a guided trail walk in Daniel Boone National Forest, Ky., in July 1966. (Forest Service photo F-514898) |

The Big South Fork NRA

Another National Recreation Area in the Southern Appalachians that was still in the preliminary development stage in early 1981 was the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area in McCreary County, Ky., and Scott County, Tenn. The Big South Fork basin of the Cumberland River, although rich in coal deposits, had not been extensively mined or developed, because of the high sulfur content of the coal as well as the physical limitations imposed by the narrow shoreline, high cliffs, and generally rugged terrain of the river basin. The area was largely uninhabited, most of its acreage owned by the big Stearns Coal and Lumber Co., which had bought the land around 1900. [26]

Since the end of World War II, the Corps of Engineers had tried unsuccessfully to win Congressional approval of an almost 500-foot dam on the Big South Fork near Devil's Jump for hydroelectric power and flood control. The dam was generally supported by local legislators and was strongly sponsored by the Kentucky Senator, John Sherman Cooper; it was opposed by private power companies: the Kentucky Utilities Co., the Cincinnati Gas and Electric Co., as well as the Associated Industries of Kentucky.

In 1967 Howard Baker was elected Senator from Tennessee. During the 1950's and early 1960's, Baker had represented the Stearns Coal and Lumber Co. in litigation and in efforts to persuade the Forest Service to allow strip mining under Stearns' reserved mineral rights. Between 1962 and 1966, he served on Stearns' Board of Directors. [27] Shortly after his election to the Senate in 1967, the fate of the Big South Fork was decided, Baker called various government officials together to determine the best development strategy for the area; the plan to develop an NRA was an administrative and legislative compromise. [28]

Authorized under the Water Resources Act of March 7, 1974, the NRA was to encompass approximately 123,000 acres. Of these, 3,000 belonged to the State of Tennessee, 1,000 to the Corps of Engineers, and about 16,000 lay in the Daniel Boone National Forest. All public lands were to be transferred to the National Park Service—the designated managing Federal agency—when sufficient private land had been acquired. [29] The Federal land acquisition agency, as well as planner, designer, and construction agent of the NRA, was the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The Corps' land acquisition program began in August 1979, when Stearns Coal and Lumber Co. sold 43,000 acres of surface rights, and 53,000 acres of mineral rights, in the Big South Fork area, for $16.5 million. (Although the authorizing legislation did not require that subsurface rights be acquired for the NRA, it did prohibit prospecting and mining. Thus, the Corps of Engineers felt obligated to acquire mineral rights as well as land.) During 1980 several smaller tracts were acquired, including those of over half the 38 families living in the area. By March 1981 about half the privately owned land remained to be acquired, but the timetable for that acquisition was uncertain, depending as it did upon congressional appropriation.[ 30]

Local reaction to the development of the National Recreation Area was mixed. Although at first McCreary County citizens, having long supported the Corps dam, were generally opposed to the NRA, by 1978 many were beginning to regard the development favorably. There was some feeling that the area might prove a major tourist attraction, even to the point of tacky overdevelopment, characteristic of Gatlinburg. [31]

However, in spite of the promises of local economic boom assured by NRA promoters, the former Forest Service employee of McCreary County, L. E. Perry, was scornful:

Some local leaders have been brainwashed to the point they believe the National Recreation Area . . . is holy salvation, placidly accepting the fact that not one major highway leading from Interstate 75 to anywhere near the Big South Fork is in the foreseeable future, which is further proof that the people of the region have been had. [32]

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the National Trails Systems Act, which also guided recreational development in the Southern Appalachians, were passed in 1968. The former established a system of rivers judged to possess "outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreation, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, or other similar values" to be preserved in a free-flowing state. [33] Rivers of the system were classified as "wild," "scenic," or "recreational," depending on the degree of access, development, or impoundment they possessed; each class was to be managed according to a different set of guidelines. The Act designated 8 rivers, all west of the Mississippi, as the first components of the system, and named 27 others to be considered for wild and scenic designation. By 1980, only two Southern Appalachian rivers had been designated part of the Wild and Scenic Rivers System—the Chattooga River, forming the border between northeastern Georgia and northwestern South Carolina, and a portion of the New River near the western North Carolina-Virginia border. [34]

The Scenic New River

Controversy

A 26.5-mile segment of the New River in Ashe and Alleghany Counties, N.C., was designated a "scenic river" in March 1976 by the Secretary of the Interior. [35] This designation was a deliberate obstruction to a development proposed in 1965 by the Appalachian Power Co. called the Blue Ridge Project, designed to provide peak-demand power to seven States in the Ohio River Valley. The project would have created two reservoirs—one in Grayson County, Va., the other in Ashe and Alleghany Counties, N.C.—totalling over 37,000 surface acres. The reservoirs would have dislocated nearly 1,200 people and over 400 buildings. Nevertheless, the project promoters promised the local population construction jobs and revenues from reservoir recreational visitation. [36]

Citizens of the North Carolina counties affected by the Blue Ridge Project organized a protest against it. A National Committee for the New River, based in Winston-Salem, N.C., mounted a well-financed publicity campaign with letters, brochures, and reports. [37] By 1973, the commissioners of Ashe and Alleghany Counties, and the two candidates for governor of North Carolina, denounced the Blue Ridge Project and endorsed the preservation of the river. [38] In 1974, the North Carolina legislature designated 4.5 miles of the New River a State Scenic River. Public pressure was applied at the Federal level through the Federal Court of the District of Columbia, which was responsible for the Federal Power Commission license, through the Congress, and through the Department of Interior. Although the FPC license was upheld in March 1976, the Secretary of the Interior designated the 26.5-mile portion of the New River as part of the national Wild and Scenic River System 3 weeks later, in effect revoking the FPC license. [39]

The Final Environmental Statement prepared by the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, although conceding that the scenic river designation resulted in the projected loss of some 1,500 temporary construction jobs, and a certain loss in projected increased land values adjacent to the reservoirs, emphasized the benefits of the scenic designation. These were principally intangible—the preservation of a unique, free-flowing river, the preservation of wildlife and of archeological and geological assets, and the preservation of a way of life in an Appalachian river valley. The direct recreational benefits from the scenic designation to the local communities were estimated to be low. The activity areas to be established along the river were expected to accommodate annually 50,000 canoeists, hikers, and picnickers. Private entrepreneurs were anticipated to have little opportunity for riverside development, due to the existence of easements and floodway zoning. [40]

Incorporation of the New River segment into the Wild and Scenic River System provoked little local protest. In general, the scenic designation brought only minor changes to life along the river. Nearly 5 years after the designation of the New River segment, the County Manager of Ashe County summed up its impact as "very little." [41] The State of North Carolina, which has managed the 26.5-mile, 1,900 acre river segment, established a State park along a portion of its banks; a few canoe rental firms and river outfitters receive seasonal revenues from recreationists. Overall, however, inclusion of the New River in the Wild and Scenic Rivers System has had only a small local impact.

|

| Figure 113.—Family hiking party at spectacular falls over a bald on upper Toxaway River near Toxaway Lake, Transylvania County, N.C., Nantahala-Pisgah National Forests. Spot is southwest of "Cradle of Forestry" and Brevard, N.C., near the South Carolina State line, about 15 miles from the upper Chattooga River; July 1964. (Forest Service photo F-511344) |

The Wild Chattooga River

The designation of the Chattooga River had larger repercussions. Public reaction was more outspoken, largely because most of the nearly 57-mile segment of the river, which included over 16,400 acres of adjacent land, was designated "wild" and was therefore slated for more restrictive management, and because the Forest Service sought to acquire lands along the river to establish a protected corridor.

The Chattooga River portion of the Wild and Scenic Rivers System was so designated by legislation of May 10, 1974. [42] The designated river segment lay within the Nantahala National Forest and on the border between the Chattahoochee and Sumter National Forests. A corridor up to 1 mile wide was outlined for acquisition along the designated river. In 1974, 47 tracts consisting of nearly 6,200 acres had to be acquired for the river corridor. [43] By early 1981, 85 percent of the desired corridor acreage had been acquired, mostly through exchange, and all from willing sellers.

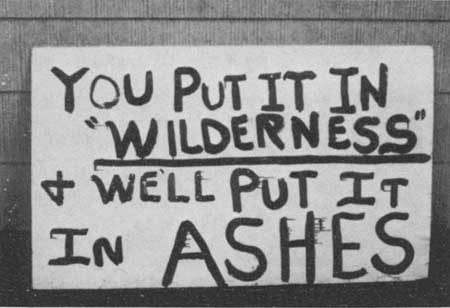

In general, acquisition along the Chattooga River proceeded smoothly; land management of the area, however, met with considerable local protest. Because some 40 miles of the 57-mile corridor were designated "wild," river access was deliberately restricted in keeping with the guidelines established by BOR. These guidelines stipulated that administration of a wild river required restricted motorized travel, removal of homes, relocation of campgrounds, and the prohibition of structural improvements. [44] Consequently, upon land acquisition, the Forest Service closed several of the jeep trails that had provided river access. Not all the river jeep trails were closed, just those the Forest Service judged were allowing excessive and inappropriate use of the Chattooga that was not in keeping with its wild and scenic designation. [45]

The rationale for restricting access, however, was not strongly supported or well understood by the local population. As an Atlanta newspaper reported:

When the Forest Service attempted to keep the jeeps away from the protected Chattooga River, the mountain dwellers torched vast tracts of National Forest land; if they couldn't use the land as they wished, they wanted no one else to use it at all. [46]

Over the years, as the Chattooga River became increasingly popular with urban recreationists for white-water canoeing, rafting, and camping, local resentment mounted. In 1980, nearly 130,000 visitor-days were spent in watercraft recreation along the 57-mile river segment; 70,000 were spent in swimming, and 60,000 in hiking. Altogether, the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River received nearly a half-million visitor days of use in 1980. [47] With a high frequency of visitors, it appeared to some local people that the Forest Service was catering to outsiders who came to the Chattooga to canoe, raft, and camp. Those who lived in the area often resented the restriction on using four-wheel drive vehicles. As one Clayton, Ga., resident wrote to the Forest Service in 1978:

Special interest & minority groups, plus environmentalists got the Government to close off the Chattooga River, in Rabun County. Look at the river now & it is more filthy and more trashy, from no one but people who ride the river, & if any, very few local people ride the river. Local people of Rabun County don't destroy beauty, it's our home. [sic] [48]

|

| Figure 114.—Hiker passing new Forest Service sign on Appalachian Trail at Rock Gap, Nantahala Mountains, in Standing Indian Wildlife Management Area of Nantahala National Forest southwest of Franklin, N.C., near Georgia State line, which is much closer as the crow flies than sign indicates. Photo was taken in July 1960. (Forest Service photo F-494684) |

The Appalachian Trail

Another piece of post-ORRRC recreational legislation was for the full development and protection of the Appalachian Trail. The Trail, running for over 2,000 miles from Georgia to Maine, mostly along the high ridges of the Appalachians, was actually originally cleared and built between 1925 and 1937 by the Appalachian Trail Conference, a group of Trail enthusiasts composed of outdoorsmen, parks and planning staff, foresters, and governmental officials, in cooperation with State and Federal agencies. Most of the Trail was constructed by volunteers, on private lands, whose owners gave permission. Nearly a third of the Trail was built by the Forest Service and National Park Service on their lands. Both agencies have helped promote and maintain the Trail. [49] In the Southern Appalachian forests, 441.4 miles out of a total 592, or 75 percent, were "protected" before 1969 with an acquired right-of-way or scenic easement. [50]

The same was not true, however, of those portions of the Trail not under Forest Service or Park Service jurisdiction. Over the years, as the Appalachian Trail received increasing public use, concern for the Trail's protection and uniform management mounted, resulting in the National Trails System Act of October 2, 1968. [51] The Act established a national system of recreation and scenic trails, with the Pacific Coast Trail and Appalachian Trail as the major components of the system. The former was to be administered by the Secretary of Agriculture, the latter by the Secretary of the Interior, although specific stretches of either trail were to be managed directly by the agency whose land the trail traversed.

Specifically, the National Trails System Act charged the Secretary of the Interior with establishing the right-of-way for the Appalachian Trail, provided that, "insofar as practicable," it coincided with the right-of-way already established. [52] The required dimensions of the right-of-way were not specified in the 1968 Act; thus, the adequacy of Trail protection at a given location was open to interpretation. Right-of-way purchases could include entire tracts, strips of tracts, or even easements, so long as the adjacent land uses were compatible with the Trail's scenic qualities.

The authority to condemn lands of an unwilling seller for the Trail right-of-way was clearly provided in Section 7(g) of the Act but was to be utilized "only in cases where . . . all reasonable efforts to acquire such lands or interests therein by negotiation have failed." [53] Further, a limitation was placed on the amount of land that could be taken—no more than 25 acres per mile of Trail. Most condemnation cases simply involved clearing title to the land. An example of a tract that in 1980 appeared likely for such condemnation was the Blankenship tract along the Tennessee-North Carolina border, owned by more than 50 heirs. Condemnation would clear title, but all 50 owners had to be contacted before the suit could begin, and the proceedings were obviously complicated. [54]

Until 1978, unprotected stretches of the Appalachian Trail were acquired by the various jurisdictions with acquisition authority, but generally—except for the Forest Service—at a desultory pace. The slowness was due largely to the multiplicity of agencies and States responsible for right-of-way acquisition and management. This was compounded by the fact that the two principal Federal agencies—the Park Service and Forest Service—were unable to develop a uniform approach to Trail policy, which, in part, was due to differing interpretations of the 1968 Act. [55] The Park Service maintained that a mile-wide strip on either side of the Trail, that was free of parallel roads, which had been established in a 1938 Forest Service-Park Service agreement, was the appropriate right-of-way. The Forest Service stressed that the Trail right-of-way could not exceed 25 acres per mile. [56]

In addition, the two agencies disagreed over the funding and timing of Trail purchases. The National Trails System Act established a $5-million fund for Trail purchases that the Forest Service felt it could draw upon. The Park Service considered this fund to be for State purchases only. Further, the Park Service imposed acquisition deadlines on the Forest Service that were impossible to meet, given the time-consuming nature of surveys, title searches, and buyer-seller negotiations. Several deadlines were established and subsequently extended. [57] Nevertheless, between 1969 and mid-1977, 110 miles of the Appalachian Trail in the National Forests of the Southern Appalachians were acquired. Of the 61 tracts involved in this acquisition, 4 were obtained through condemnation: one in the Nantahala, 2 in the Pisgah, and one in the Cherokee. [58] By mid-1981, only 14.3 miles (2.1 percent) of the 677.0 miles for which the Forest Service has responsibility in the mountains of four States were unprotected. Of the 263.5 miles delegated to the National Park Service, 42.8 miles (16.2 percent) were still unprotected. [59] A summary of the status of Appalachian Trail protection in the Southern Appalachians in October 1981 is shown in table 20.

Table 20,—Protection status of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail in the Southern Appalachians, October 1981

| USDA Forest Service |

National Park Service, USDI |

State-owned land | ||||

| Location of trail |

Protected | Still to be protected |

Protected | Still to be protected |

Protected | Still to be protected |

| miles | miles | miles | ||||

| Virginia | 303.7 | 4.4 | 152.0 | 42.8 | 18.6 | 6.0 |

| Tennessee-North Carolina | 208.9 | 9.9 | 68.7 | none | none | none |

| Georgia | 78.1 | none | none | none | none | none |

| Total | 662.7 | 14.3 | 220.7 | 42.8 | 18.6 | 6.0 |

Source: Land Acquisition Field Office, Appalachian National Scenic Trail, U.S. Department of the Interior, Martinsburg, W. Va., Tennessee and North Carolina mileage is combined because much of the trail follows the State line. Virginia data includes stretches not included in the study area of this publication.

Amendments to the National Trails System Act passed in 1978 substantially improved the administration of the Trail acquisition process and clarified most of the management problems. [60] Substantial additional funds were provided for acquisition, and condemnation authority was extended to allow acquisition from unwilling sellers of up to 125 acres per mile of Trail. In addition, the amendments stipulated that the acquisition program was to be "substantially complete" by the end of fiscal year 1981 (September 30). [61]

Under the 1978 amendments, the acquisition process proceeded with available funding. [62] By January 1981, all but 14 miles of Trail strips in the Southern Appalachian National Forests had either been acquired or were in the final stages of acquisition. Most of the remaining private tracts involved appeared to be obtainable only through condemnation, Some were held by implacable owners who simply refused to sell. John Lukacs, as resident of Florida, was one. Lukacs owned about 1,500 acres in the Cherokee National Forest, near Johnson City, Tenn., which he planned to develop someday. The Appalachian Trail cut diagonally across one small corner of his property. The Forest Service wanted to purchase a strip of land along the Trail as well as the 11.6-acre "uneconomic remnant"—the corner cut off by the Trail. Lukacs refused to sell, citing as his reason a spring in the corner remnant. In 1978 the Forest Service referred the case to the Department of Justice for prosecution. [63] Late in 1981 Justice agreed to press ahead with the suit.

Another long-resistant owner was the Duke Power Co., which had several large tracts along both sides of the Trail on the Tennessee-North Carolina State line in the Cherokee and Nantahala National Forests. Duke Power finally exchanged its Nantahala tract for equivalently valued National Forest acreage. Although the Forest Service needed only a narrow strip nearly 5 miles long, Duke insisted on selling the whole Cherokee tract intact, about 1,705 acres. The Forest Service made an offer which was refused by Duke, but after another potential buyer dropped out, further negotiations produced agreement on the sale price for the whole tract and the Forest Service set aside funds for it. Completion of the purchase was expected by early 1982. This would reduce the agency's remaining Trail strip to be acquired to less than 10 miles out of its total Trail responsibility of 677 miles in the four affected States, less than 1.5 percent. [64]

|

| Figure 115.—The static mountain community of Nada, Powell County, Ky., on old State route 77 which tunnels through the mountain close by and forms part of the Red River Gorge Loop Drive on the Daniel Boone National Forest. The modern Mountain Parkway also now passes near the town, and the Frenchburg Civilian Conservation Center, established 3 years before the photo was taken in September 1968, is just a short distance sway. A scene still common today throughout the Southern Appalachians. (Forest Service photo F-519027) |

Kentucky Red River Gorge

Aside from Mount Rogers and the Appalachian Trail, the only other location in the Southern Appalachians where the Forest Service has taken lands from unwilling owners by condemnation for recreational purposes was the Red River Gorge of the Daniel Boone National Forest. Named a geological area in 1974, the Gorge covers 25,663 acres along the north and middle forks of the Red River, in Powell, Menifee, and Wolfe counties, Ky. Once part of an ancient sea and the product of centuries of weathering and erosion, the area is unusually scenic, with natural arches, caves, bridges, and rocky outcrops along the cliffs of the gorge. It has been managed as a special forest unit, both for recreation and to protect and preserve a unique environment. Lumbering is prohibited in the Gorge. [65]

Condemnation in the Red River Gorge has been used to acquire summer-house lots held by absentee owners along Tunnel Ridge Road, a high-use portion of the area. Altogether five tracts involving 45 acres have been condemned, although several owners have sold under threat of condemnation. [66] In 1973, when the Forest Service's draft plan for the Red River Gorge was developed, the Red River Area Citizens Committee protested the use of condemnation. Since 1973, some Red River inholders, having observed its use in spite of their opposition, began to protest any additional Federal land acquisition. The Gateway Area Development District, for example, passed a resolution in April 1979 opposing "further acquisition of land within the . . . area." [67]

The opposition appears to have been inflamed by the RARE II proposals to designate nearly one-half of the Red River Gorge (Clifty area) as wilderness (to be discussed later); however, the concern developed out of general experience with Forest Service acquisition policies and procedures. As in the cases of Mount Rogers, Chattooga River, and the Appalachian Trail, legislative development and Forest Service management plans appeared to threaten, with little warning, the pattern of local landownership. In the Red River Gorge area many people believed that, although the Forest Service usually aired its land-management alternatives in public, it often did not adequately inform them of final land-use decisions. Because people sometimes felt uncertain of their options, the threat of Federal acquisition was not entirely removed. [68] As long as the Federal Government was a neighbor, the mountaineer felt he could never be certain that his land would remain his own.

Private Recreation Business Is a Major

Force

One conclusion of the ORRRC report was that the "most important single force in outdoor recreation is private endeavor—individual initiative, voluntary groups . . . , and commercial enterprises." [69] Indeed, the heightened Federal attention to outdoor recreational resources and and Federal legislation passed following the report apparently triggered a substantial private recreational development, particularly in the Southern Appalachians. The natural beauty of the region and its proximity to the population centers of the East were recognized as assets that had not been fully exploited. National corporations opened new resorts in the mountains; vacation home communities spread in clusters outside the National Forests; the number of retail establishments catering to tourists increased, and speculators bought numerous tracts of mountain land, throughout the region, hoping to turn a profit by subdividing. The impact of these actions was considerable, not only on the local population but also on the managers of Federal land.

In its first years, the Appalachian Regional Commission funded a series of studies to ascertain the potential role of the recreation industry in the region's economic development. The benefits of tourism to the local population had long been acclaimed by recreational developers seeking to gain support for their programs. Promoters of the Blue Ridge Parkway and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park had both predicted a regional tourist boom. [70] Nevertheless, although recreational visitation and tourism in the Southern Appalachians increased dramatically over the years, by 1960 no such boom had developed.

The first ARC study in 1966 concluded that the economic impact of recreational development on local areas is "marginal" and should be justified principally because it gives open-space recreation to people living in metropolitan areas. It cautioned that recreational employment is seasonal, low-paying, and undemanding, and that the indirect benefits of tourism are small. Thus, the 1966 ARC report pointedly advised, "major public investment in non-metropolitan recreation resources would rarely be justified solely or even primarily, for the sake of the economic impact on the local area." [71] So the recreation industry, like the timber industry, was not the solution to Appalachia's economic ills. Nevertheless, seemingly ignoring the prudent findings of its first study, and favoring the rosy BOR report of 1967, ARC continued to encourage heavy recreational development. [72] In 1967 the Commission began an inventory and analysis of selected multicounty sites, 23 of which were labeled of greatest potential. Twelve such sites were in the Southern Appalachians, and seven of these, all relatively undeveloped, were selected for further analysis. [73] All seven were near, or enclosed, National Forests, National Parks, or TVA reservoirs. Thus, the large Federal landownership in the region was recognized as a major recreational asset. Private investment, it was felt, could "piggy-back" on the existing recreational attraction of public sites.

For example, the Upper Hiwassee River Interstate complex, a seven-county highland area of northern Georgia, southeastern Tennessee, and southwestern North Carolina, just south of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, was credited with enormous potential because of the Chattahoochee, Cherokee, and Nantahala National Forests and four TVA reservoir lakes. However, the area lacked road access, accommodations, and camping spaces. Although it was implied that Federal or State funds would be required for roads and other public services, ARC said private developers could profitably build hotels, motels, and second homes. [74] Similarly, the Boone-Linville-Roan Mountain complex in the Pisgah National Forest section of North Carolina, just east of the park, was seen to exhibit "great potential" for attracting vacationers, especially skiers. [75] Overall, the ARC study concluded, if the 14 recreation sites were fully developed, by 1985 there would be a $1.7-billion "total economic impact." Even in the smallest counties where a lower level of expenditure could be assumed, "a sizable amount of private business development and/or expansion could be expected, and services would probably be considerably expanded." [76]

In 1960, private recreational development was not spread evenly over the Southern Appalachians; rather, it was concentrated in distinct county clusters. The principal clusters were near Great Smoky Mountains National Park—Sevier and Swain; in the Nantahala National Forest—Graham, Jackson, and Macon; the northern Georgia counties in the Chattahoochee National Forest—Towns, Union, Fannin, and principally, Rabun; and Watauga and Avery counties, in the upper Pisgah National Forest, near Boone, N.C., and the Blue Ridge Parkway. Clearly, the National Forests, parkway, and National Park of the region were integral to the development of the private tourist-recreation industry. [77]

Nevertheless, physical recreational resources alone do not explain the locational pattern of the recreation industry. Hancock County, Tenn., for example, one of the 12 study counties we chose for more detailed analysis, located north of Knoxville near Cumberland Gap, had "a mountain environment, clean air and streams, an uncommercialized and unspoiled countryside, and a unique county culture group . . . . Tourists, however, have not visited the county in large numbers." [78] Major factors in recreational development were relative ease of access and a resort history. That is, the counties with the greatest recreational growth in this period were those that had a history of tourism and that seemed unable to attract other economic activities, because of their remoteness. [79] Southern Appalachian counties with the most lodgings and tourist-related jobs were relatively inaccessible, lacked a diverse economic base, but had been frequented for many years by vacationers.

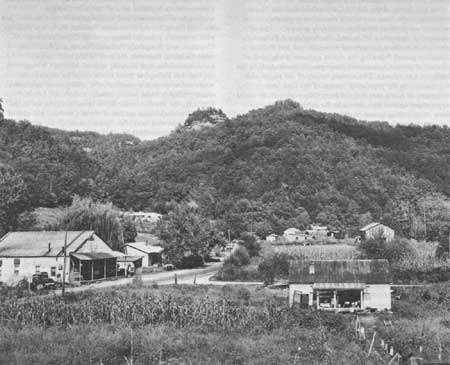

The Federal lands that provided the regional recreation base attracted vacationers throughout the 1960's and 1970's, most of them at an increasing rate. Statistics for the fiscal years 1972-80 reveal the general trend, as shown in figure 116. [80] The Chattahoochee and Jefferson National Forests did not show substantial visitor growth over the 8-year period, and the Cherokee did so only in 1980, when visitation increased 150 percent over 1979. In the four North Carolina forests, it increased steadily by 240 percent over the period. In the Daniel Boone, including the Redbird unit, the peak was reached in 1976. Notably, compared to all National Forests in the United States, the Daniel Boone and North Carolina forests rose dramatically as ranked by number of recreation "visitor-days" reported. By 1980, the Daniel Boone ranked 26th out of 122 National Forest units; the North Carolina forests jointly ranked eighth. [81]

|

|

Figure 116.—Volume of Recreational Visitation in

Southern Appalachian National Forests, 1972-80. 1Includes the small Croatan and Uwharrie National Forests of the Piedmont and coast. 2Includes the small Oconee National Forest of the Piedmont. Source: "Resistive Standings of the National Forests According to Amount of Visitor-days of Use," Recreation Management Staff, Forest Service, Washington, D.C. A visitor-day is any aggregate of 12 person-hours, ranging from one person for 12 hours to 12 persons for one hour each. |

Private Development Varies

Greatly

The extent of private recreational development that occurred during the 1960's and 1970's varied considerably from county to county across the Southern Appalachian region. Some became the focus for heavy second-home development; others grew in commercial facilities; others, although remaining relatively important as recreational concentrations, developed very little. One area that achieved wide publicity for its heavy, uncontrolled commercial development is Gatlinburg, Sevier County, Tenn.—western entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. [82]

During the 1980's changes in landownership began to occur suddenly in the Gatlinburg area where for years land had been closely held by a few families. After 1960 "outsiders with no apparent intention of establishing residency . . . increased their holdings." [83] Most of these "outsiders" were northern corporations, such as Rapoca Resources Coal Co. of Cincinnati, or national chains, such as Holiday Inn. A very high number of franchise or chain ownerships located there. [84]

Investments were made not only in resort attractions (resort hotels, restaurants, and shops), but in residential land as well. Individuals and corporations bought acreage all around Gatlinburg, so that by 1972 almost half the landowners were outsiders. Many of them bought land for summer or retirement homes but some, with no intention of settling, bought for pure speculation. Although in the mid-1970's sizable tracts outside Gatlinburg were still in the hands of local inhabitants, the slightly more distant tracts, upon which higher capital gains could be realized, were largely in the hands of outsiders. [85]

Although the town was unusual in the Southern Appalachians in that it had been an established resort area for several decades, its pattern of land development by outside investors was repeated throughout the region. Watauga and Avery Counties, N.C., were heavily developed in the 1960's, first by local entrepreneurs. For example, Hugh Morton transformed Grandfather Mountain into a recreational complex that included condominiums, a subdivision of Scottish manor houses called Invershiel, a lake, and the Grandfather Mountain Golf and Country Club, with a professional golf course. [86] His family had owned some 16,000 acres of mountain land since the end of the 19th century; when his father died, Morton inherited the mountain as a parcel of land no one else in the family wanted. Although a movement was started to purchase Grandfather Mountain for the National Park Service, Morton finally decided to develop the land. With the aid of professionals, he built one feature after another. By 1978, Grandfather Mountain boasted, in addition to traditional resort facilities, a bear habitat, a nature museum, and a mile-high swinging bridge.

Later, corporate developments, such as Sugar Mountain and Beech Mountain, owned by Carolina-Caribbean Corp. of Miami, followed. Some Winston-Salem businessmen and the L.A. Reynolds Construction Co. built Seven Devils nearby. All included golf courses, lakes, tennis courts, and ski slopes, as well as second homes spread in subdivision fashion across the hills. [87]

Northern Georgia has also attracted heavy recreational investment, particularly in vacation-home communities, As of 1974, approximately 210 second-home subdivisions were being "actively developed" in 12 counties, some as large as 5,000 to 9,000 acres. [88] On a smaller scale, the Highlands area of Macon County, N.C. became the site of many second homes whose owners had permanent residences in Atlanta, Savannah, Jacksonville, and other southern urban areas. [89] However, recreational subdivisions per se did not become a common feature of the southwestern North Carolina landscape. In the 11-county "Southern Highlands" region of North Carolina, including Buncombe, Henderson, Graham, Macon, and Swain Counties, there were only 12 second-home development firms that controlled 30 or more homes or sites each in 1973. Macon County, had the most, with four. [90]

The increase in second-home development throughout the Southern Appalachians was part of the general reversal of the heavy outmigration the region experienced in the two decades after World War II. As discussed in chapter VII, between 1970 and 1975 a distinct change in migration patterns occurred in all study counties; either net outmigration slowed dramatically or net inmigration took place. This shift appears to have applied across the whole region, and must be seen as part of a national change. In general, over the United States as a whole, after 1970, nonmetropolitan areas attracted increasing numbers of people while Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas lost population. In particular, nonmetropolitan places of a recreation or retirement character attracted heavy numbers of inmigrants. Although the Sunbelt States were the chief recipients of inmigrants, parts of the Southern Appalachians previously identified as areas of recreational development were also among the migration-destination targets. [91]

No Economic Boom Results

However, in spite of the isolated clusters of resorts, the localized proliferation of second homes, and the reversal in migration trends, recreational development in the Southern Appalachians in the 1960's and 1970's did not create an economic boom. Development was initiated largely by individual or corporate outside investors, and secondary growth was often limited. Ten years after the initial ARC recreational study of 1966, reports and statistics of actual results generally confirmed this study's conclusion that the net economic impact of recreational development on the Southern Appalachian region would be "marginal."

For example, over the 11-county area of southwestern North Carolina, almost no growth occurred in the local recreation industry between 1966 and 1972. Specifically, the North Carolina Outdoor Recreation Areas Inventory discovered an actual decline in the number of resorts offering camping and recreation/amusement facilities between 1966 and 1972. This decline was most extreme for commercial resorts, which dropped in number by 25 percent; whereas resorts on government land actually increased by 60 percent. [92]

Employment in recreation-related businesses over the 11-county area generally increased between 1960 and 1970; however, as a percentage of total employment, recreation business employment showed little gain. Only employment in construction and in hotels, lodging places, and amusement services increased, both absolutely and relatively. Employment in eating and drinking places, gas stations, and real estate experienced relative declines. [93] The only real recreation-related growth shown was in the actual number of firms servicing the recreation, tourist, and second-home market. [94] This growth, however, may more accurately reflect exogenous investment than it does local capital development.

Over the Southern Appalachian region as a whole, as represented by the 12 study counties, growth from recreational development can be partially gauged from the increase in the number of, and sales from, eating and drinking places. Table 21 shows these increases over the years for which data are available:

Table 21.— Eating and drinking places in 12 selected Southern Appalachian counties: number and percentage of total retail sales, 1972 data compared to 1954 and 1967

| High proportion of National Forest |

Little or no National Forest | |||||||||||

| Year | Union, Ga. | Graham, N.C. | Macon, N.C. | Unicoi, Tenn. | McCreary, Ky. | Bland, Va. | Habersham, Ga. | Ashe, N.C. | Henderson, N.C. | Hancock, Tenn. | Knox, Ky. | Buchanan, Va. |

| Number of eating and drinking places | ||||||||||||

| 1954 | 6 | 4 | >11 | 14 | 5 | 2 | 16 | 5 | 44 | NA | 16 | 20 |

| 1972 | 12 | 8 | 27 | 19 | 8 | 5 | 23 | 14 | 49 | 2 | 27 | 28 |

| Percentage of total retail sales from eating and drinking places | ||||||||||||

| 1967 | 2.0 | 10.0 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 4.4 | D1 | 4.7 | 3.4 |

| 1972 | 3.7 | 11.3 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 4.1 | D | 4.6 | 4.7 |

1D=Disclosure laws prohibit publication for only one or two firms.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, County and City Data Book, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1957, 1967, 1972).

Although the number of eating and drinking places increased in both the counties with a high proportion of National Forest land and those with little or none, the percentage increase was greater for the former group. For two thirds of the former, the number of eating and drinking places at least doubled, an increase that suggests the rise in tourism those areas experienced. Similarly, that group of counties showed a gain in the relative importance of sales from eating and drinking places between 1967 and 1972; whereas, over the same period, the relative importance of such sales generally decreased in the latter group. This differential probably reflects the failure of the heavily national-forested counties to build as broad an economic base as those counties without much such land, as well as their increase in recreational development. [95]

Pace of Recreational Development

Slows

Although the recreation industry of the heavily national forested counties experienced a period of relative growth in the 1960's and 1970's, the extent of neighboring Federal landownership was no assurance of a successful recreation investment. The pace of development has slowed. For example, the privately owned Bear Paw Resort on Lake Hiwassee in the extreme southwestern corner of the Nantahala National Forest—one of the areas identified by ARC as showing substantial recreation development potential—suffered major financial losses during most of the 1970's. [96] The resort, a 99-acre complex with 40 rental cottages, built by TVA when the Hiwassee Dam was constructed, included tennis courts, a swimming pool, an ice-skating rink, marina, stables, and restaurants. In 1979 the North Carolina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development negotiated to buy the property for a State park. But, as one of the owners lamented, "the thing is a loser. There's no way for us to make money or even for the state to . . . The property isn't worth $200,000, so far as a going concern . . ." The purchase did not take place. [97]

Furthermore, whatever growth may have occurred in the recreation industry in selected counties during the 1960's and 1970's, the employment in the industry was repeatedly acknowledged to be small, sporadic and low-paying. [98] In 1975, in 12 mountain counties of North Carolina, where recreational development was a feature of the landscape, only 6.6 percent of the labor force worked in the recreation industry, and then only seasonally, for low wages. [99] As Lewis Green of Asheville has written, in spite of the promises developers make for the local economy:

. . . all that one can see for the little man is maintenance and custodial jobs. Maids and waitresses. At the end of the season, the big money goes to Florida—to return here again to buy up some more old homeplaces. [100]

Even more significant, some feel, is the fact that such employment introduces "a job orientation no longer directly associated with the land." Although in itself such orientation may not be bad, it "serves to undermine the spirit of independence so long characteristic of the mountain people, and places them in a position of almost perpetual subordination to the outside-dominated financial manipulators." [101]

During the 1960's, commercial and individual private land acquisition began to alter the mountaineer's perception of his land. Land became "significant as property," and valued for financial investment. [102] On the whole, private investment in the Southern Appalachians during the 1960's and 1970's substantially inflated the price of land. In southwestern North Carolina, "hilly woodland that sold for $50 to $100 [per acre] in 1955 could have easily been sold ten years later for $450 and more." [103] Such inflation consequently raised property valuations, causing increased property taxes, and thus a higher property tax base. Whether such changes were ultimately beneficial or detrimental is open to some controversy. Edgar Bingham has described the circumstances that have led to the inflation of land values:

Buyers from . . . large corporations . . . offer prices for land which unsuspecting natives find difficult to refuse. The prices offered are in truth inflated relative to the value of the land in its traditional subsistence or semi-subsistence farm use . . . . Many sell, assuming that they will buy other property within the general area, but they find that land values overall have gone up radically, so they either must give up their former way of life and become menials for the developer, or, as is often the case, they leave the community altogether. Even those who are determined to retain their land find that its value has become so inflated that it is no longer practical to use it for farming, so either they become developers themselves or they sell to the developer. [104]

This process has been clearly documented in Ashe, Avery, and Watauga Counties, N.C., where the number of out-of-State landowners and the amount of land they owned increased dramatically between 1960 and 1980. [105] A study by the North Carolina Public Interest Research Group found that outside speculators increased their landownership by 164 percent in Watauga County and 47 percent in Avery County between 1970 and 1975. [106] One result of such increase is that, as land values inflated, farmers found it more and more difficult to pay taxes. By the mid-1970's, approximately half the farmers in Watauga and Avery Counties worked at least 100 days per year off their farms to supplement their incomes. The long-range predicament is that, as farmland prices escalate, a farming career ceases to be viable. [107]

Net Benefits Are Questionable

Although second-home developments and investments in mountain land increased the property tax base of many Southern Appalachian counties, the cost of services also increased considerably. Due to a lack of substantive documentation, it is not certain whether revenues kept up with costs. The 1966 ARC study found that resorts and vacation homes generally strengthen the property tax base. Also, because the highest single item of public expenditure—education—is usually not increased as a result of recreational development, the study claimed that vacation homes and establishments do "yield a profit on the municipal balance sheet." [108]

However, a mid-1970's study of the Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina State agencies responsible for recreation suggested that the cost of providing services to second-home developments can be more than the increased taxes they generate, particularly if the developments are not adjacent to existing population concentrations. [109] Specifically, Avery and Watauga Counties, with very limited road-maintenance budgets, allowed ski roads in demand for tourist developments to be maintained, while farm roads suffered. Hospitals, fire departments, and police all were found understaffed and underfinanced to handle the temporary vacationing population. [110] Similarly, in Sevier County, Tenn., three resort developments studied by the State Planning Office in 1977 were found to have cost the county at least $23,000 more in services than they generated in tax revenues. [111]

In addition, many have claimed that resort and recreational home development in the Southern Appalachians has brought environmental degradation similar to that resulting from the exploitation of timber and coal resources decades earlier. [112] Problems of erosion, inadequate water supplies, and sewage treatment facilities have been cited. [113] Some of the degradation has been clearly visible, as the description of a Rabun County, Ga., development, named Screamer Mountain, testifies:

Seen from a helicopter, it is as though an entire mountain had been assaulted by a road-building spider and left entangled and throttled in a network of gouges and tracks. Since this development is dense and the gradients are steep, much of the vegetation is gone; mud turning to liquid mud in the rain, is left behind. Since this development constitutes a mountain, it is visible from all sides. It is particularly worthwhile to imagine several such developments on the tops of approximately contiguous hills. These fortresses of deforestation, frowning upon each other across their several valleys, would then constitute their inhabitants' only views . . . . It is hard to see what amenity would remain. [114]

Such visual blight has occurred largely because most counties in the region have not had appropriate zoning or land use controls. In North Carolina, although most county governments have zoning ordinances, they are generally of poor quality, and are often set aside or lightly administered under economic pressures. In addition, development has often taken place in the unincorporated areas of a county, where land-use controls have been even more lax. [115]

Big Influx of Temporary

Residents

Finally, recreational development has brought to the mountains a new group of temporary residents, most of whom have a value system and attitude toward the land that are alien to the mountaineer. Writing of the suburban newcomers, Bingham has explained:

The effect on the human population [of recreational development] over recent years has been to replace the natives with "new" mountaineers. Mountaineers without a real attachment to the land and whose demands or expectations have tended to be in conflict with rather than in harmony with the mountain habitat. His automobiles, motorcycles, and the service vehicles meeting his more elaborate demands clog the mountain roads and disturb the rural quiet with the roar of their engines. His ski slopes have cut huge slashes in the natural cover of the most attractive mountains, and the most appealing trails and associated vistas suddenly become off-limits to the people who have always lived here. [116]

Perhaps the greatest misunderstanding between the old and new mountaineer is in the matter of trespass. The southern mountaineer has his own sense of landownership rights. Holding title to the land is but one type of possession; long residence in an area entitles one to certain rights as well—for example, free access for hunting, wood gathering, and berry picking. This attitude toward the land is based on historical precedent; in the past, each farmer had his own bottomland acreage but regarded the forested ridges as common ground. [117]

Thus, although over 4 million acres in the region were in Federal ownership, local residents still felt free to use much of that land in the traditional way. As George Hicks has written:

Timber is recognized as private property and one must buy trees before cutting them. Scavenging for fallen tree limbs to use as firewood, however, falls into the same category as galax: it belongs to the gatherer. The same is true for wild fruits—huckleberries, blueberries, blackberries, and so on. [118]

Although permits were required for some activities—tree cutting, gathering evergreens, or hunting—the Forest Service at times overlooked violations. As Hicks wrote of local use of the North Carolina National Forests, "evergreen collectors take it as a game to evade the forest rangers and Federal officers, and they declare that the officials have a similar playful attitude." [119] A similar "game" has been observed between local hunters and Forest Service personnel along the Appalachian Trail:

"Foot Travel Only" trails ... [are] being (hopefully, at least) protected by Forest Service signs designed to exclude two-wheeled and four-wheeled vehicles. During hunting season, it seems that the signs are taken down and hidden; and vehicles enter. Violators profess innocence . . . claiming they saw no signs excluding vehicles. To combat this, the Forest Service erects heavy wooden posts. The posts are cut down with chain saws, and vehicles obtain entrance. The Forest Service retaliates with more wooden posts, and this time drives one-inch thick steel rods diagonally through the posts and into the ground. And so the battle goes on . . . each side thinking of new ways to outwit the other. [120]

When the new group of vacation homeowners and resort developers came, they established the boundaries of their newly acquired property with fences and often "No Trespassing" or "No Hunting" signs. [121] This exclusion became a source of misunderstanding and antagonism. Why, the mountaineer reasoned, was he prohibited from woodgathering or hunting on lands his family had used for years? Incidences of arson were traced to such resentment. In Macon County in 1976, an outbreak of fires struck a sawmill, several patches of woods, and a tourist attraction called Gold Mountain. A man was later quoted as saying, "The posted signs burned right off early. They didn't last no time." [122]

Because the mountaineers, the newcomers, and the Forest Service staff live in close proximity throughout the mountains, a triangular relationship developed in which the Forest Service was often perceived by the mountaineers to be catering to the ways of the newcomers. There was a "conflict—real or perceived—between the expectations and desires of forest users distant from the forest scene and local economic aspirations." [123] The forest officers, following administrative directives from Washington, felt caught in the middle. In no case was this situation more dramatic than in the battles that were staged during the late 1970's over wilderness.

|

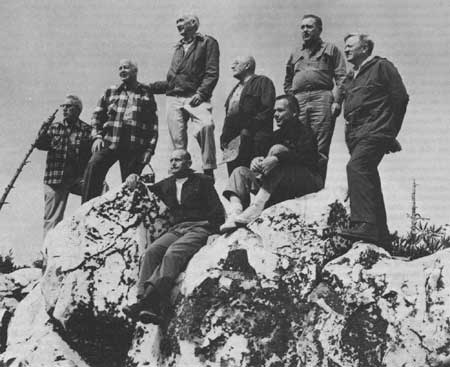

| Figure 117—Prominent wilderness leaders who accompanied Forest Service officials on a 4-day "show-me" trip through National Forests in the Southern Appalachian Mountains, were here looking over the new Shining Rock Wild Area, later called Wilderness, from the crest of Shining Rock on the Pisgah National Forest, N.C., in September 1962, 2 years before passage of the Wilderness Act. The spot is near the "Pink Beds," "Cradle of Forestry." and Blue Ridge Parkway, southwest of Asheville and not far from Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Standing, left to right, were: North Carolina National Forests Supervisor Peter J. Hanlon; Southern Regional Forester James K. Vessey; Harvey Broome, a lawyer and co-founder in 1934 of the Wilderness Society, a leader in the Great Smoky Mountains Hiking Club; William W. Huber, Southern Regional information chief; Pisgah District Ranger Ted S. Seeley; and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas. a hiking and wilderness enthusiast. Seated: Ernest M. Dickerman, then director of field services, eastern region, Wilderness Society, later also Washington representative of Tennessee Citizens for Wilderness Planning, and (1982) vice-president of Conservation Council of Virginia; and Charles Rickerhauser. (Forest Service photo F-504012) |

Wilderness Act Sparks Much

Conflict

The Wilderness Act of September 3, 1964 gave Federal statutory recognition to wilderness designation through the establishment of a national system of wilderness areas. [124] The Act was the culmination of 8 or 9 years of intensive legislative debate and lengthy testimony. The first wilderness bill had been introduced by Senator Hubert Humphrey in 1956 following the opposition to and defeat of the proposed Echo Park Dam on the Green River in Dinosaur National Monument, northern Utah and Colorado. That preservation-versus-development controversy illustrated both the political power of militant conservationist groups and the substantial base of their popular support. [125]

Debate over the Wilderness Act focused on three issues: the amount of land to be included in the wilderness system; the addition of lands to the system; and the status of logging and mining in wilderness areas. [126] Most timber, mining, petroleum, agriculture, and grazing interests opposed the legislation; the Forest Service, although a pioneer in establishing wilderness areas, also was strongly against the bill at first, largely because its administrative and land-management prerogatives would be restricted. The statement in the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960 that "the establishment and maintenance of areas of wilderness are consistent with the purposes and provisions of . . . multiple use," anticipated to some extent the wilderness legislation to come. [127] Support for a separate wilderness act was strong, however, and the Forest Service ultimately acceded to the popular movement, lending its expertise to the long bill-drafting and modification process.

The Wilderness Act defined wilderness areas as places "where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." Wilderness areas were to be preserved in a roadless, forested, undeveloped condition. Specifically prohibited in the wilderness system were motor vehicles (land or water), motorized equipment, and the landing of aircraft, except where already established, as well as permanent buildings and lumbering. In general, hunting, fishing, and grazing (but not crop farming) were allowed. Where rights had been previously established, mining and prospecting could continue until January 1, 1984.

The wilderness system defined by the Act incorporated over 14 million acres of areas that were already being administered by the Forest Service as wilderness. In 1924 its Southwestern Region had established the Gila Wilderness Area in New Mexico. In 1929 the Forest Service had set aside large primitive areas in the West and upper Great Lakes region for protection under Regulation "L-20." In 1939 the "U" Regulations formally established a system of wilderness, wild, and primitive areas. (Later the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in Minnesota, much of which had been pledged by the Secretary of Agriculture in 1926 to remain roadless, was added as a distinct administrative entity.) Lumbering, roads, commercial establishments, motor boats, and resorts were all prohibited in the system. Except for size, Forest Service wilderness and wild areas were the same; wilderness areas were larger than 100,000 acres, wild areas were between 5,000 and 100,000 acres. Primitive areas were tracts set aside for further study, although they were administered as wilderness. Altogether, in 1964, the system encompassed over 14,600,000 acres. [128]

The Wilderness Act included the Forest Service's 54 previously designated wilderness and wild areas as the sole initial components of the national wilderness system. Its 34 primitive areas, which accounted for over a third of the 14,600,000-acre system, were to be reviewed over a 10-year period for possible inclusion. Each area could be added to the system only by an act of Congress; prior to congressional action, each area had to be the subject of a public hearing where testimony from Governmental officials and private citizens would be taken.

By 1973, only three areas in the East, formerly designated wild areas, had been included in the wilderness system: Great Gulf, in the White Mountain National Forest in New Hampshire, and Linville Gorge and Shining Rock, both in the Pisgah National Forest. In designating wilderness, the Forest Service had maintained a strict interpretation of its own guidelines. [129] In the East, where most lands had been occupied, logged, or burned, only a few select areas of more than 5,000 acres qualified for wilderness consideration. However, the 7,655-acre Linville Gorge and 13,400-acre Shining Rock tracts were not altogether free from the imprint of man; parts of both areas had been logged and burned about 1900. [130]

However, the national movement for wilderness was strong. Local conservationists expressed dissatisfaction with the exclusion by definition of all but a few eastern lands from the wilderness system. [131] Furthermore, the eastern areas that had been designated wilderness were experiencing a phenomenal increase in public visitation. Linville Gorge and Shining Rock had a recreational use of 5,300 and 5,200 visitor-days respectively in 1968; by 1974, the figures were 21,800 and 12,400 visitor-days. [132] Recognizing the pressure for designating more areas as eastern wilderness, the Forest Service in 1972 asked conservation organizations and natural resource associations for recommendations on ways to classify and preserve wilderness in the East, taking into consideration the special problems posed by the fragmented landownership pattern, the fact that most mineral rights were privately held, and the fact that most rivers and bodies of water within National Forests were not federally owned. [133]

Beginning in 1972, bills were introduced in Congress to establish a special wilderness system; the Eastern Wilderness Act of 1975 resulted. [134] The bill did not attempt to define wilderness as such, but catalogued the value of wilderness as, "solitude, physical and mental challenge, scientific study, inspiration and primitive recreation," Altogether, the Act designated 16 eastern National Forest areas totaling over 207,000 acres as the initial components of the system. Five of the areas were in the Southern Appalachians, as listed in table 22.

Table 22.—New areas designated in Southern Appalachia by the Eastern Wilderness Act of 1975.

| Wilderness | National Forest | Acreage |

| Beaver Creek | Daniel Boone (Ky.) | 5,500 |