|

Mountaineers and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern Appalachians, 1900-81 |

|

INTRODUCTION

At the end of the 19th century, when much of America was experiencing strong urban-industrial growth, the Southern Appalachian region of eastern Kentucky, eastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, western North Carolina, and northern Georgia was sparsely populated, nonindustrial, and very largely rural. After the mid-18th century the mountains had been settled by westward-moving pioneers in a pattern of widely scattered clusters of small farmsteads—first along the wider river bottoms, and later into the coves and up the ridges. Towns were few, small, widely separated, and connected only by narrow, rutted dirt roads. Most mountaineers lived self-sufficiently, growing corn and raising hogs, isolated from each other and the outside world by the region's many parallel ridges.

Until 1880 the rich resources had been barely touched. Steep mountainsides were covered with unusually heavy and varied hardwood forests and underlain with thick seams of coal and other minerals. Water rushed abundantly down and through the mountains on its way west to the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers, east to the Atlantic Ocean, and south to the Gulf of Mexico. Then, however, railroads penetrated the mountains, and with them came tourists, journalists, missionaries, scientists, investors, businessmen, and industrialists who found a society and economy at once pristine and primitive. By 1900 these outsiders had described and publicized the region, purchased much of the land, and were beginning to extract its resources; they had also tried to educate, reform and transform the southern mountaineers.

In 1911 the Federal Government came to the Southern Appalachians to purchase and manage vast tracts of mountain land as National Forests. The Weeks Act, passed in March of that year, authorized the Federal purchase of "forested, cut over or denuded" lands on the headwaters of and vital to the flow of navigable streams. Land acquisition under the Weeks Act focused at first principally on forests of the southern mountains. Several thousand acres were acquired within a few years. In June 1924 this Act was amended and broadened by the Clarke-McNary Act to allow purchase of timber lands unrelated to navigable streams. [1] The creation of these National Forests helped to define Appalachia as a discrete region.

In the 70 years since 1911, the Federal Government has acquired over 4 million acres of land in the Southern Appalachians, principally for National Forests supervised by the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, by far the largest single land manager in the region. Federal lands are managed for a variety of public purposes that often differ from profit-oriented private land management practices. Therefore, the effects of this massive series of purchases on the people of the region have been considerable, though subtle and gradual for the most part during the first 50 years.

Since 1960, changes in the region have accelerated, and although mountain residents are still largely wary spectators and often victims of events, they are no longer silent; their response has quickened and sharpened. They have learned to join together to at least modify some of the changes being imposed by modern society.

|

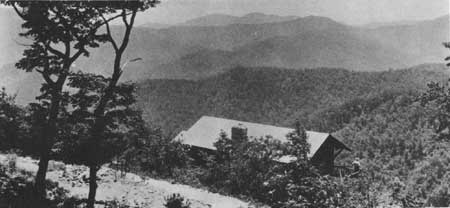

| Figure 1.—Forested ridges and slopes of Black Mountains, a section of the Blue Ridge near Mt. Mitchell, N.C., highest point in the East, on Pisgah National Forest. When photo was taken in March 1930 a new summer home had just been built under special use permit, in foreground. (Forest Service photo in National Archives, Record Group 95G-238076). |

Boundaries of the Region

As it is for any cultural region, defining the boundaries precisely is arbitrary and subjective. The region encompasses the southern half of the great multiple Appalachian Mountain chain that runs from Alabama to Maine, but its exact boundaries have varied according to the differing purposes of various studies. Often considered besides terrain are political boundaries and socioeconomic and cultural factors.

Three definitions have gained prominence. [2] John Campbell, in his 1921 classic, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland, included all of West Virginia, the western highlands of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, easternmost Kentucky and Tennessee, northernmost Georgia, and northeastern Alabama: 256 counties in 9 States. His principal criterion was physiography. [3]

In 1960 Thomas R. Ford, in The Southern Appalachian Region, outlined an area of 189 counties, 25 percent smaller area than Campbell's. Ford excluded westernmost Maryland, South Carolina, and West Virginia, and included less of Virginia, Alabama, and Tennessee. He based his region on "State Economic Areas", a concept developed in 1950 by the U.S. Bureau of the Census and the U.S. Department of Agriculture in order to group counties with similar economic bases. [4]

The Appalachian Regional Commission has provided a more recent definition. This 169-county "Southern Appalachia" stretched down to include a corner of Mississippi and almost half of Alabama, but excluded West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, putting both in a new category, "Central Appalachia". The principal criterion is weak or lagging economic development. [5]

All three definitions include a mountainous "core": far southwestern Virginia, far western North Carolina, easternmost Tennessee, and northernmost Georgia. These sections, although the most rugged and least accessible, are not all the weakest economically.

There is some doubt whether any of the above three broad regions, or even the "core", constitute a true cultural region. Geographer Wilbur Zelinsky says two features identify a cultural region: (1) how its distinctiveness is manifested (physically and behaviorally), and (2) how its people consciously behave. [6] Scholars generally have treated the Southern Appalachians as a cohesive cultural entity. Although Campbell and Ford acknowledged that the region was not culturally homogeneous, both emphasized its distinctiveness. However, others have insisted that the region is too culturally diverse to be regarded as a unit and that it is not a functional social and economic area. [7] Indeed, some have questioned whether its people show a genuine regional selfconsciousness or whether the region's cultural distinctiveness is not simply a reaction to outside forces. [8]

This study covers counties with large Federal land purchases, including the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains where the Blue Ridge Parkway was built, as well as the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina that are now largely enclosed in the National Park of that name, and part of the Cumberland Plateau in Kentucky. The major focus is on the counties of Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia that respectively contain the Daniel Boone, Cherokee, Pisgah, Nantahala, Chattahoochee and part of the Sumter National Forests, as well as the southwesternmost counties of Virginia below the New River divide that contain part of the Jefferson National Forest. Thus, this study area encompasses the core of the Southern Appalachians that all previous definitions of the region share. [9]

Nearly all of the National Forests in the eastern half of the United States stem from the 1911 Weeks Act, as amended by the 1924 Clarke-McNary Act. The justification for such purchases was at first to control erosion and streamflow through the rehabilitation, maintenance and improvement of forests. [10] In the Southern Appalachians, lands at stream headwaters were naturally the steepest, most remote, and least inhabited. In 70 years, the Federal Government has purchased over 4 million acres of land there, most of it for National Forests. [11] These purchases have been largely concentrated in the region's core and in the separate Cumberland Highlands belt of Kentucky. Today several "core" counties are more than 50 percent federally owned. [12]

|

| Figure 2.—Sparse spruce-fire growth on 5,700-foot ridge of Black Mountains, Pisgah National Forest, N.C., looking toward Pinnacle Peak, with Swannona Gap in foreground and Asheville reservoir watershed at right. (NA:95G-254616) |

Purpose of This Study

Assessing the impact of Federal land acquisition and land management on the peoples and cultures of the Southern Appalachian region is the purpose of this study. Even before the lands in question were purchased, they were special in several ways. Besides being generally the most mountainous and least accessible, they were often the least populous and most scenic in the region. Thus, even without purchase and management by the Federal Government, they might have developed differently from adjacent lands that were not purchased. It is unlikely, for example, that they would ever have supported a large population. Nevertheless, the very act of Federal purchase and the introduction of new land management techniques to the region changed its demographic, economic, and social structure. Indeed, the large Federal presence has certainly helped to shape the region's distinctive culture.

Physical Geography of the

Region

The Southern Appalachian mountains, a broad band of worn-down parallel ridges of sedimentary rocks, are among the oldest in the world. They were formed several hundred million years ago in an "accordion" effect of the movement of very deep continental plates and accompanying upheavals of the earth's surface. [13] They comprise three geologic subregions: the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Valley and Ridge section, and the Appalachian Plateau. [14]

The Blue Ridge Mountains, rising sharply from the Piedmont to form the eastern subregion, are the oldest and were the deepest layers of rocks, and so were greatly changed by heat and pressure (metamorphosed). From 5 to almost 75 miles wide, the Blue Ridge area is in some places a single ridge of mountains and in others a complex of ridges. It includes the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia and North Carolina; the Iron, Black, Unaka, Nantahala, and Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina; and the Cohutta Mountains of northern Georgia. The highest peak in the eastern United States, Mount Mitchell, 6,684 feet (2,037.3 meters) in elevation, lies within the Black Mountains and is a State Park. [15]

The Valley and Ridge subregion is a band of nearly parallel, "remarkably even-crested" ridges and river valleys; from the air it looks almost like corrugated cardboard. [16] This subregion stretches from northern Georgia northeastward slightly west of the North Carolina-Tennessee border, into southwestern Virginia and eastern Kentucky. It includes the Greater Appalachian Valley, actually a series of broad river valleys that run in broken stretches from the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia south to the valley of the Tennessee River and its tributaries. These valleys were the major avenues of immigrant travel diagonally through the mountains into the region from the mid-Atlantic States and Carolina Piedmont.

The Appalachian Plateau, a broad, uplifted area in eastern Kentucky and Tennessee, forms the westernmost subregion of the Southern Appalachians. The plateau has been so severely dissected over millennia by running streams that it appears almost mountainous, although its elevations are not nearly as high nor its slopes as steep as those of the Blue Ridge to the east. Known as the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee and Kentucky (and as the Allegheny Plateau in West Virginia) the subregion is marked on the west by an escarpment which drops down to a gently rolling piedmont. [17]

The long-stretching parallel ranges and ridges of the Southern Appalachians formed a strong barrier to westward pioneer travel. There are only a few passes: water gaps where rivers now cut across the ridges, such as the New River gap; or wind gaps, such as Cumberland Gap, where ancient, now diverted streams once cut. No river flows directly or all the way through the region covered by this study. However, the very old New River, together with the Kanawha, does flow clear across almost the entire width of the Southern Appalachians, and is the only river system to do so, just north of the study area.

Geographers have noted the "odd behavior" of rivers in the Southern Appalachians. The main rivers begin as many mountain streams that drain, first in trellis patterns and then at right angles, across the ridges to the west. In contrast, the rivers north of Roanoke, Va., drain to the east. [18] Only the Chattooga and Tallulah Rivers of northern Georgia, and the Yadkin, Pee Dee, and Catawba Rivers of North Carolina, originate in the mountains and drain to the Atlantic; the remainder flow west or southwest. The Clinch, Powell, Holston, Watauga, Nolichucky, Tellico, Little Tennessee, Pigeon, Nantahala, French Broad, Hiwassee and Toccoa-Ocoee Rivers all flow into the Tennessee River, which passes by Chattanooga and the northwestern corner of Georgia into Alabama before turning northward to join the Ohio River in Kentucky. The New River, actually the oldest in the region, joins the Kanawha, which also drains into the Ohio. The streams of eastern Kentucky drain into the Licking, Kentucky, and Cumberland Rivers which all join the Ohio, too.

The climate of the region is mild, and rainfall is plentiful. Average annual temperature is about 65°F. (18.3°C.); growing season is about 220 days. Rainfall is fairly uniform throughout the year, usually accumulating between 30 and 50 inches (76.2 and 127.0 cm.); in the Nantahala and Great Smoky Mountains up to 80 inches (203.2 cm.). In general, slopes facing south and southeast are warmer and drier than those facing north and northwest. [19]

|

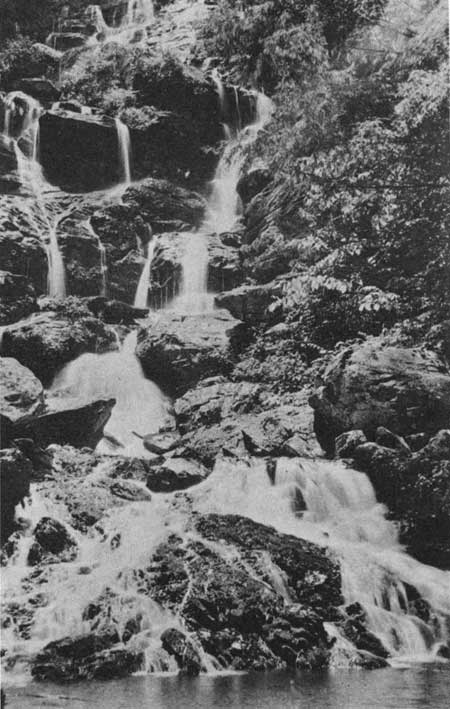

| Figure 3.—Cascades near headwaters of Catawba River between Old Fort, N.C., and Black Mountain, east of Asheville, Pisgah National Forest; photo taken in June 1923. (NA:95G-176371) |

Flora, Fauna, Coal, Minerals

Abundant

Because of its geological history and climate, the Southern Appalachian region possesses an abundance and great variety of trees, at least 130 species, perhaps the greatest variety of any temperate region in the world. Species distribution varies with location and altitude. Up to 2,500 feet (762 meters) above sea level, oak forests predominate; principally red, chestnut, scarlet, white, and black oaks, as well as shortleaf pine, various species of hickory, black gum, sourwood, dogwood, and red maple. Before the disastrous blight early in this century, American chestnut was a major and exceedingly valuable species. Between 2,500 and 3,500 feet (1,067 meters) in elevation, yellow- (tulip) poplar, white pine, hemlock, birch, beech, walnut, and cheery are abundant. Above 3,500 feet, black spruce and balsam fir forests cover the mountain slopes. Dense undergrowths of rhododendron and mountain laurel are common in much of the region. In general, the heaviest rainfall and most luxuriant forest are on the protected northwestern-facing Blue Ridge slopes. [20]

The region's forest is home for an unusual variety of fauna. Although most of the species are rodents and other small mammals, many have provided a rich quarry for hunters. Deer, squirrels, black bears, raccoons, opossums, grouse, and wild turkeys abound. Until they were eliminated or driven from the region early in this century, elk and wolves were present in the Southern Appalachians; foxes and bobcats remain. Wild boars, which were imported from Europe in 1912 and introduced near the Tennessee-North Carolina border south of the Great Smokies persist on remote slopes. [21]

Soils are of disintegrated and decomposed sedimentary rock. Each subregion has its own typical soils; those of the Blue Ridge are most subject to erosion and those of the greater Appalachian Valley most conducive to productive cultivation. The alluvium in the broader river valleys is fertile and productive if not overworked, and the region's bottomland soil is excellent for growing corn, beans, and other garden vegetables. However, some mountain soils are thin, rocky, and infertile; when exposed on steep slopes, they can become severely eroded. [22]

The Southern Appalachians are rich in coal deposits, both bituminous (soft) and anthracite (hard), as well as true minerals. Most of the coal is high-grade bituminous, concentrated in eastern Kentucky, where it lies close to the surface of the folds and ridges of the earth in horizontal beds from 8 to 10 feet thick. Kentucky coal thus can be easily stripped or mined by boring horizontally into a mountainside. The Valley and Ridge subregion of Virginia and Tennessee also contain high-quality coal, much of it anthracite, that is usually mined in deep shafts. The Southern Appalachians contain reserves of limestone, copper, manganese, and sulfur, all of which have been mined with varying degrees of financial success over the last century. [23] They are also presumed to contain sizeable deposits of oil and natural gas. Recent geological research has shown the mountains to be underlain to a depth of 12 miles with layers of sedimentary rock, the kind least likely to have dispelled hydrocarbons and therefore most likely to contain natural gas and oil. [24]

Thus, the region is unique in its geology and physiography, and has natural assets which contribute to its distinctiveness. The physical geography of the Southern Appalachians greatly influenced its settlement and early development, as well as the way the region was perceived and used throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

|

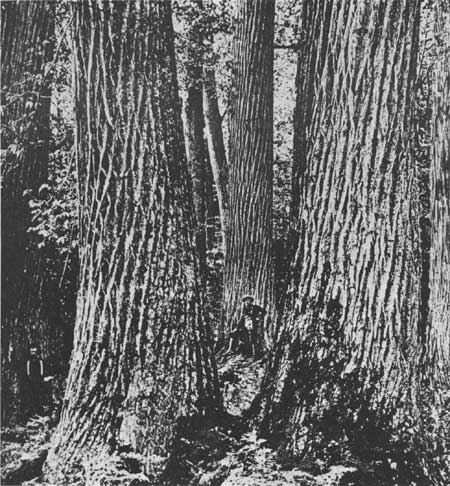

| Figure 4.—A group of huge old "virgin" American chestnut trees up to 13 feet in diameter deep in the Great Smoky Mountains of western North Carolina; photo taken about 1890. Note the men at left and center. A foreign blight wiped out this extremely valuable species between 1900 and 1930. (Photo courtesy of Shelley Mastran Smith). |

Settlement of the Southern

Appalachians

Thousands of years before white men settled the Southern Appalachians, aboriginal Indians inhabited the area. Archeological evidence suggests human activity over most of western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, northeastern Georgia, and northwestern South Carolina as early as 10,000 to 8,000 B.C. Throughout the Blue Ridge and the Valley and Ridge subregions, weaponry and domestic tools have been discovered that suggest a mobile hunting civilization evolving slowly over the millennia. By 1000 to 1650 A.D. the Cherokees, as the largest group of Indians came to be known, were cultivating corn, beans, squash, sweet potatoes, and fruits in scattered, nucleated villages, where Europeans encountered them. [25]

The first European to see the mountains may have been Hernando DeSoto who, on an expedition from Florida in 1540, named them after the Appalache Indians. Next were John Lederer and his party, sent in 1669 by Virginia's Governor, William Berkeley, to discover a route to the western Indians. Over the next 50 years, several more expeditions explored the Blue Ridge area, primarily for Indian trade, but none resulted in permanent settlement. [26]

The Southern Appalachians were settled after 1730 by pioneers of western European stock searching for more freedom and abundant land. For 100 years considerable pioneer traffic to the west moved through the gaps of these mountains. [27]

The early settlers were primarily Scotch-Irish Presbyterians from northern Ireland and Palatinate (west Rhine) Germans. The latter immigrated in large numbers between 1720 and 1760, fleeing religious persecution and economic hardship. They settled first in Pennsylvania, gradually moved westward, then, along with others, ventured down the Greater Appalachian Valley of Virginia and North Carolina. Other early settlers moved inland from the Carolina Piedmont, over the ridges into Kentucky and Tennessee, which became States in 1790 and 1796, respectively. They traveled by wagon and horseback, following river valleys and Indian game trails, crossing the parallel ridges where streams had cut through the mountain chains at places like Saluda Gap just south of present-day Asheville, on the North Carolina-South Carolina line, and Cumberland Gap, the furthest west point of Virginia, on the Kentucky-Tennessee border.

Most pioneers moved through the Southern Appalachians to the Ohio River valley, on to Missouri, Arkansas, and further westward. But a permanent population, attracted by the mountains, remained in the valleys and coves to live by hunting, stock raising, and simple farming. By 1755 the Cumberland Gap area had several permanent clusters of dwellings; Watauga became the first settlement in Tennessee in 1768. [28]

After 1810, the stream of pioneer settlers began to slow, and by the 1830's it had all but stopped. The last major influx of pioneer migration to the Southern Appalachians occurred after gold was discovered near Dahlonega, Ga., in 1828. By 1830 between 6,000 and 10,000 persons lived in northern Georgia, but many left when the gold rush ended. [29]

After the major settlement phase, people and goods between East and West still passed through the Highlands. Merchandise from eastern ports was transported on primitive roads. Large livestock herds were driven from the interior across the ridges to Baltimore, Philadelphia, and to the cotton plantations. Travelers heading west might meet droves of as many as 4,000 or 5,000 hogs heading to market. In 1824 it was estimated that a million dollars' worth of horses, cattle, and hogs came through Saluda Gap to supply South Carolina plantations. [30] Whiskey was also frequently shipped through the mountains; it was less bulky, higher in value, and less perishable than the corn that produced it. By midcentury, however, Middle West farm products were more often shipped down the Mississippi to the East. Traffic on the mountain gap routes gradually declined.

Natives Were Cherokee Indians

When the pioneers first entered the Southern Appalachians, they encountered the Cherokee culture. Trade between the white settlers and the Indians developed early, and was the means of mutual influence. Pioneers learned from the Cherokees what crops to cultivate, how to farm, where and how to hunt. The Indians received material goods from white settlers, and soon abandoned their thatched huts for cabins with log and rail siding. [31]

The two cultures, however, did not remain compatible. Over the course of the 18th century, as settlers moved into the mountains the Indians' territory was circumscribed. Between 1767 and 1836, through a series of controversial treaties between the Cherokees and the State of North Carolina, the Indians, under severe pressure, gradually relinquished all tribal lands east of the Mississippi River. Although about 2,000 Cherokees voluntarily emigrated to the West, many were hunted down, forcibly removed and marched to Oklahoma by Federal troops after 1838. Many died on this "trail of tears." A band of about 1,000 Cherokees refused to leave and instead hid in the Great Smoky Mountains. In 1878, with the aid of an attorney, William H. Thomas, these fugitive Cherokees obtained title to over 60,000 acres of land in Swain and Jackson counties, N.C., site of the present Qualla Reservation. [32]

By the middle of the 19th century, the Southern Appalachians were fairly widely settled and the important towns established. Just as topography influenced pioneer routes of travel, so did it structure the region's settlement pattern. Settlement occurred first in the broader, flatter, more accessible river valleys, such as the Watauga, Nolichucky, Clinch, Holston, Powell, New, and French Broad, where the soil was relatively rich and productive. Asheville, N.C., on the French Broad River, started as a trading post in 1793 and was incorporated in 1797. By 1880 it had over 2,600 inhabitants. Knoxville, located at the confluence of the French Broad and Holston rivers, was founded in 1791, although a fort had been there as early as 1786. [33] Smaller river and stream valleys which cut west through the ridges were also settled early. Protected coves and hollows with arable land, good water, and abundant timber were sought as homesites. Only gradually did people occupy the steeper ridges where the terrain and rocky soils often made farming difficult. In general, ridge settlements were more characteristic of the Cumberland Plateau area than of the Blue Ridge region, where, as Ronald Eller has written, "the predominance of larger coves permitted oval patterns of settlement around the foot of the slopes, leaving the interior basin open for cultivation and expansion."

|

| Figure 5.—A 70-year-old stand of white pine with understory of sugar maple and birch high up in the Bald Mountains near Hurricane Gap and the Tennessee-North Carolina State line. Nolichucky Ranger District, Cherokee National Forest, near Rich Mountain Lookout and the Appalachian Trail, just up the ridge from Hot Springs, N.C., and the French Broad River. When photo was taken in May 1962, Ranger Jerry Nickell was marking trees for a partial cut. These northern species do well at this 3,200-foot elevation. This site along Courtland Branch is used as a dispersed camping site by visitors. (NA:95G-502184) |

Many Small Family Clusters

The mountains became a land of scattered, self-sufficient "island communities" divided by ridges and hills. [34] These communities generally consisted of small clusters of two or three homes within easy walking distance of each other. Groups of neighbors were often kinfolk as well. Later generations added to these clusters, but there were rarely more than a dozen households together. Commercial settlements often developed at a gap, at a crossroads, or at the mouth of a large hollow, but they were small, usually containing one or two stores, a mill, a church, and a school. [35] Larger towns were widely scattered and slow to grow.

From early in the 18th century, the land was divided into units later called counties, subdivided as population increased. In western North Carolina this process took 150 years. Rowan, the first, was formed in 1753; Avery, the last, in 1911. County seats were smaller and less important than elsewhere in the South. [36]

Until about 1900, mountain communities were connected to each other and outside points only by narrow rutted, muddy or dusty roads that inhibited frequent or long-distance travel. Nevertheless, the isolation was much like that of most communities in early 19th-century rural America. Mountaineers traded with nearby communities, worked seasonally outside the mountains, received letters and periodicals through the mail, and were visited by occasional peddlers and local politicians. [37] Mountain people had some access to new goods and ideas.

The relative isolation of the region become more pronounced after the Civil War. Although the war engaged the sentiments of many, it did little to alter the economy and settlement of the region. The rise of industrialization and urbanization was slow to reach it. Not until more than a decade after the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869 did a rail line cross the region. The mountains were then gradually opened to tourists, travelers, and investors. In the 1880's timber and mining interests began to acquire mountain land, and the region's population started to swell.

By 1900 industrialization had finally arrived. However, impacts for long were only scattered and fragmentary. The settlement pattern survived, and the self-sufficient family farm remained dominant. In 1900 only 4 percent of the region's population could be classified as urban (living in places of 2,500 people or more). Asheville, the largest city, had a population of 14,694, while the neighboring centers of Knoxville and Chattanooga, across the mountains on the Tennessee River, each boasted counts of over 30,000. Other large mountain towns were Bristol and Johnson City, Tenn.; Middlesboro, Ky. and Dalton, Ga., each with over 4,000 people. Several mountain counties had one town of at least 1,000, but many counties had no village with more than 500 people. [38] Larger towns were usually county seats, but there were notable exceptions, such as Middlesboro, near Cumberland Gap. [39] The most populous areas were the Asheville vicinity, northeastern Tennessee, and southwestern Virginia. These Tennessee and Virginia areas each had four counties with over 20,000 inhabitants. Least populated were the highlands of extreme southwestern North Carolina and northern Georgia. Both Clay and Graham Counties, N.C., for example, had fewer than 5,000 people.

Population density over the region was about 35 per square mile in 1900, and some counties had less than 20, like Rabun, Ga.; Leslie, Ky.; Bland, Va.; and Graham, Swain, and Transylvania, N.C.

|

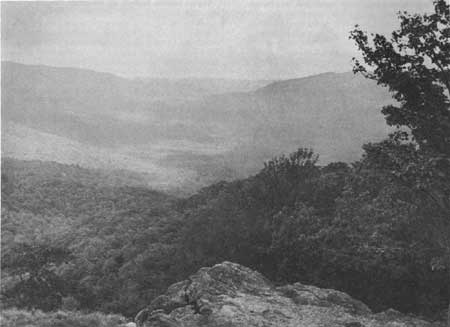

| Figure 6.—The "Pink Beds-Cradle of Forestry" area of the old Biltmore Forest of William Vanderbilt, nucleus of the Pisgah National Forest just south of Asheville, N.C. Panoramic view was taken from Pounding Mill Overlook on U.S. highway 276 about 1950. (Photo from National Forests in North Carolina) |

Fast Population Growth

In the last decades of the 19th century, the rate of population growth in the Southern Appalachians was greater than for the Nation as a whole. For the 79 counties in the region's core, the rate from 1890 to 1900 was about 23 percent. For the United States it was 20.7 percent. The growth varied considerably from State to State, however. Kentucky led the mountain counties with 34 percent during the 1890's; northern Georgia had only 14 percent. Certain counties grew by more than 50 percent over the decade, primarily coal counties, such as Wise (100 percent) and Dickerson in Virginia, and Leslie (70 percent), Bell, Harlan, and Knott, in Kentucky. Some noncoal counties also spurted.

Although only 4 percent of the region's population was urban in 1900, about one person in four lived in nonfarm homes (33 percent in eastern Tennessee and 40 percent in southwestern Virginia, both of which had more small towns; Virginia also had larger farms). Most farms in the region in 1900 were between 50 and 175 acres, averaging about the same as that for the States involved and for the South Atlantic region, but smaller than the 147-acre average for the Nation as a whole. [40] Typical ranges of farms by size are in table 1.

Table 1.—Number and percentage of farms by size in four typical Southern Appalachian Counties, 1900

| Size of farm in acres | Union, Georgia | Graham, North Carolina | Unicoi, Tennessee | Bland, Virginia | ||||

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Under 3 | None | 0 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 3 | Under 1 |

| 3-9 | 36 | 2 | 22 | 3 | 64 | 9 | 25 | 4 |

| 10-19 | 91 | 6 | 45 | 6 | 98 | 15 | 37 | 6 |

| 20-49 | 245 | 17 | 137 | 19 | 189 | 28 | 104 | 16 |

| 50-99 | 395 | 27 | 212 | 29 | 149 | 22 | 118 | 18 |

| 100-174 | 419 | 29 | 185 | 25 | 104 | 15 | 149 | 23 |

| 175-259 | 140 | 10 | 64 | 9 | 32 | 5 | 89 | 13 |

| 260-499 | 93 | 6 | 40 | 5 | 16 | 2 | 82 | 12 |

| 500-999 | 22 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 32 | 5 |

| Over 1000 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 21 | 3 |

| Totals | 1444 | 100 | 732 | 100 | 678 | 100 | 660 | 100 |

The independence and self-sufficiency of the Southern Appalachian farmer is generally confirmed by farm tenure statistics for 1900. Most farms in the region (about two-thirds) were owner-operated; however, the second highest category of tenure, "share tenants," indicates an increasing tendency toward absentee landlordism and tenancy in general. In some counties, as many as 30 percent of all farms had share tenancy. This situation was one reflection of the outsider investment and changes in landownership that began toward the end of the 19th century. [41]

Although modern enterprise was beginning to bring significant changes, there was in 1900 only small-scale and scattered industry. Most counties of Appalachian North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia had from 50 to 100 factories; those in Georgia and Kentucky usually had less than 50. These firms did not employ many people. Less than 1 percent of the region's population earned wages in manufacturing. Even in Asheville's Buncombe County, the 208 factories employed only 3 percent of the people.

Thus, industrial development was nascent and the small, 100-acre, owner-occupied farm prevailed in the core of the region, which would within two decades experience major Federal land acquisition. The mountains were only partially populated and cleared, towns were small and few, and settlements were scattered.

Marginal, Self-Sufficient Farms

In 1900 the marginally self-sufficient family farm—in Rupert Vance's words, "the modus vivendi of isolation"—was still the most significant element in the economy of the Southern Appalachians. Unlike other rural areas of the country, especially the nonmountain South where the raising of a single cash crop prevailed, the mountain farm remained diversified. Before the Civil War at least, the mountain farmer produced up to 90 percent of the products he needed. [42] By 1880 the region had a greater concentration of noncommercial farms than any other part of the United States.

In the late 1800's the typical mountain farm contained both bottomland and steep hillsides. About a quarter was in crops, a fifth in cleared pasture, and the remainder, over half, was in forest. Springs and a nearby creek provided plentiful water. About half the land under cultivation was devoted to corn, which provided a household staple and the basis for whiskey, as well as grain for horses and hogs. Secondary crops were oats, wheat, hay, sorghum, rye, potatoes, and buckwheat. An orchard of apple and other fruit trees was planted. Many farmers had their own bee hives, and every farm had a large vegetable garden where green beans, pumpkins, melons, and squash were commonly grown. Contour farming was still unknown there. Crops and gardens often stretched vertically up the side of a hill, hastening erosion, runoff, and siltation of mountain streams. [43]

Mountain farmers cleared land for cultivation by felling the largest trees and burning the remaining vegetation. Indeed, burning was the accepted practice of "greening" the land, including woods for browsing, in the spring and "settling" it in the fall. The fires were set to destroy rodents, snakes, and insects, and to clear underbrush. The thin layer of ash left added a small nutrient to frequently depleted soil, the only inorganic fertilizer then known to mountain farmers. Once lands became unproductive through overcultivation or erosion, they simply cleared more adjacent forest and abandoned garden plots to scrub.

A variety of livestock helped make the mountain family self-sufficient. A few milk cows, a flock of chickens, a horse or mule, or a yoke of work oxen, and a dozen or more shoats (pigs) were found on nearly every farm. Sheep were often raised for their wool, which the women weaved into clothing, blankets, or rugs. Geese were useful for insect and weed control and for their down which was plucked for bed quilts and pillows. A good hunting dog or two were necessary to keep rabbits and groundhogs out of the garden and for the year-round hunting of rabbits, squirrels, quail, and other wild game to supplement the farm's meat supply. [44]

Usually 8 to 12 people—parents, children, and occasionally grandparents or other relatives—lived on the farm. Aided by a horse or mule, the family performed all the work necessary to provide its own food and shelter. The center and symbol of mountain life was the farm home itself. Homes were usually built in sheltered spots with good water readily accessible and within easy walking distance—but not sight—of neighbors. The traditional mountain homested was a handhewn log cabin, usually one room with a loft, front porch, and possibly a lean-to at the back. When sawmills became more prevalent throughout the region in the late 1800's, small frame houses were built. Eventually two- to four-room box houses and larger frame houses became more common. However, log cabins continued to be built in more isolated areas well into the 20th century. [45]

A limited exchange occurred between farms, between farms and towns, and between farms and distant markets. From the earliest settlement until the 1880's, the principal commercial activity was the raising of livestock. Cattle, hogs, and other animals were allowed to roam the forest freely or were driven to pasture on the ridges or high grassy mountain "balds," which resulted from forest fires. The most important animal for sale was the hog. Fattened on the abundant chestnuts, acorns, walnuts, and hickory nuts, and "finished off" before sale or slaughter on several weeks' diet of corn, mountain hogs provided considerable ham and bacon for the South. Throughout the 19th century cattle and hogs were driven at least semiannually from the mountains to markets in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia, and even to Baltimore and Philadelphia. The practice continued even after the coming of the railroads, although crops and bacon were also shipped by rail to such markets as Chattanooga and Augusta. [46]

Timber, Herbs, Honey, 'Moonshine' Add to

Income

Mountaineers also supplemented their incomes with occasional timber cutting. Small-scale logging provided work during the winter and an opportunity for trade. Some families operated small, local steam-engine sawmills. Some produced wood products such as chairs, shingles, and fenceposts for exchange with their neighbors or local merchants. Until the early 20th century when it was wiped out by a foreign blight, chestnut was the favored Southern Appalachian wood, readily marketable as timber or finished product, and its nuts (mast) were an important food for hogs and wildlife.

The forests provided the mountaineer with other abundant marketable produce. For many families, the gathering of medicinal herbs and roots was an important commercial activity. In late summer the family would collect yellow-root, witch hazel, raspberry leaves, spearmint, sassafras, golden-seal, and bloodroot (used for dyes). Ginseng and galax were especially important forest plants. Ginseng is a perennial herb with a long aromatic root, long favored by the Chinese for its supposed stimulant properties. It was heavily gathered from 1850 to 1900 until its supply was severely depleted. Galax, an evergreen ground cover used especially in floral arrangements, became an important collectible toward the end of the century. A town in Grayson County, Va., is named after galax. Such plants were often used as exchange for household items at local stores. Merchants receiving the plants dried and packaged them for shipment by wagon and later railroad to distribution centers in the Northeast. Between 1880 and 1900, merchants paid $2.00 to $5.00 for a pound of ginseng root collected in the forests. [47]

Families also supplemented their incomes by trading products of their fields, kitchens, and parlors, such as jams, honey, apple butter, woven and knitted goods, and illegally distilled liquor. Indeed whiskey ("moonshine") became the fundamental, unique, virtually universal domestic industry of the Southern Appalachian region after the Civil War when the tax on it skyrocketed. As Rupert Vance has written, distilling was a natural outgrowth of the combined circumstances of corn production and relative isolation. Corn was the chief cash crop cultivated, but its transportation was "a baffling problem." Therefore, instead of being carried to market as grain, it was transmuted to a more valuable condensed product: its essence was conveyed by jug. [48] In some hollows particularly northwestern North Carolina, tobacco became an important cash crop. Surrey, Madison, Burke, Catawba, and Buncombe counties had sizeable acreage in tobacco from 1880 to 1900, but this crop faded there as piedmont and coastal tobacco became more popular. [49] It is still grown in some mountain sections near Winston-Salem, however.

Only rarely would a mountaineer actually receive cash for the livestock, timber, whiskey, roots, sweets, or herbs he might trade. Barter was universal. There were few banks in the mountains until after 1900. Before railroads and industrialization, local merchants extended credit and exchanged their wares for the produce of the mountaineers. A good source of cash was seasonal fruit picking. Thousands of mountain men traveled to lowland orchards at harvest time, and took most of their wages back to their families. [50] On the whole, however, mountaineers seldom saw cash.

|

| Figure 7.—Illustrative of the rich home crafts tradition of the Southern Appalachians was Mrs. Lutitia Hayes, seated with many of the blankets and quilts she had made, in front of her home in Clear Creek, Knott County, Ky., in September 1930. (NA:95G-249152) |

Isolation Fosters Independence,

Equality

The relative isolation and self-sufficiency of the 19th-century Southern Appalachians fostered a loose social and political structure that emphasized independence and equality. Since mountain settlements were clusters of extended families, religious, social, and political activities were organized along kinship lines.

The concept of equality—that any man was as good as another—flourished in a setting where most people owned their own land and made their living from it with family labor. Slavery existed in mountain counties before the Civil War, but it never had a significant impact. In traditional mountain society, social divisions were not based on wealth but rather on status derived from the value system of the community. In mountain neighborhoods where economic differences were minimal, personality or character traits, sex, age, and family group were the bases for social distinction. Thus, the rural social order was simply divided into respectable and nonrespectable groups, with varying degrees in each. [51]

In larger towns, however, a class consciousness based on wealth was more evident. Wealthier, landed families who controlled local businesses and provided political leadership formed a local elite, as elsewhere in the South. They sent their sons outside the mountains to be educated, to become teachers, lawyers, doctors, and businessmen. [52] Using their political influence, education, outside contacts, and comparative wealth, members of these families played an important role in the region's industrialization. They purchased land and mineral rights from their neighbors for sale to outsiders, and they publicized and promoted the development of transportation improvements, especially the railroads, often acquiring large fortunes as a result. [53]

Political activity in the Southern Appalachians was informal, personal, and largely based upon ties of kinship. Respected patriarchs and commercial leaders often obtained political power. They relied on family ties to get elected and, having won elected office, were expected to look out for their kinfolk. National or State politics were of little concern to the mountaineer. Political interest was largely in local matters and the election of county officials: the county attorney, superintendent of schools, circuit court judge, and the sheriff. [54]

Political activity centered on the county courthouse. What the VanNoppens have written of western North Carolina can be said of the region as a whole:

The courthouse was to the county seat what the cathedral was to a medieval city: it expressed the hopes and aspirations of the people. It was . . . the shaper of human lives and destinies. It was the center of government and authority. It brought order and system to the wilderness . . . It was the focal point of the social life, the occasion when those from one cove could meet and gossip with their neighbors from other coves and ridges, whom they had not seen for months. [55]

Thus, when circuit court met in the county seat several times a year, many families attended the sessions to shop and meet with friends and relatives. On election days large crowds gathered to be entertained by campaigning politicians. Until the turn of the century voting was by voice rather than secret ballot and voters would often stay all day, waiting to see how the election came out. [56]

|

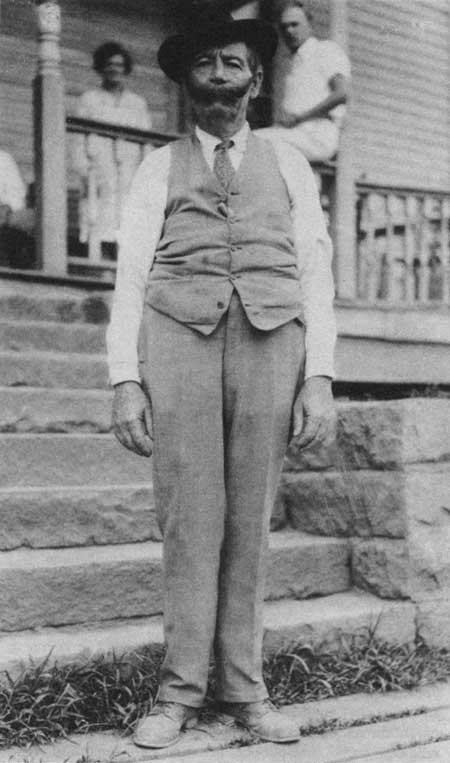

| Figure 8.—Jim Perkins, who then was county attorney in the tiny Knott County seat of Hindman, in the bitumimous coal belt of eastern Kentucky, August 1930, then a severely depressed area. (NA:95G-247046) |

Churches, Schools Are Simple

The strong egalitarianism and independence of the mountaineer were reflected in the prevailing forms of religious belief and practice. Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists, and Lutherans were the chief denominations of the Southern Appalachians, although the area fostered hundreds of smaller sects as well. In the 18th century, Presbyterian were dominant among the pioneers. This denomination, however, is highly organized and rigidly structured, emphasizing formal ritual, and with a firm requirement for a well-educated ministry. Thus, it was not readily adaptable to life in the small, isolated, unlettered neighborhoods of the mountains. Baptists became by far the most successful of the Protestant denominations, here as elsewhere, founding thousands of churches which grouped under the Southern Baptist Convention. [57] It was less structured, more democratic, and appealed strongly to the emotions. When members were too far from an established church to attend services regularly, they formed their own congregation. By 1900 Baptists accounted for well over a third of the total membership in religious groups of the region. [58] For 100 years, Baptist splinter groups and other small sects had developed, each expressing its variety of a down-to-earth, simple, emotional Christianity of sin and personal salvation. Although the Bible was the supreme religious authority, each person was free to interpret it. [59]

Education in the Southern Appalachians until well into the 20th century was largely informal, sporadic, and practical. In the smallest and most isolated settlements, one family member would serve as instructor in the rudiments of reading, writing, and mathematics for all the neighboring kin. The school term, only 3 to S months long, depended on weather and crop conditions. Meager tax money deprived teachers of equipment and materials. School houses were one- or two-room log cabins, poorly lighted, with fireplace or stove. Glass windows were rare before 1900. Teachers were young and inexperienced. County seats and more affluent communities established independent grade-school districts with 9-month terms that attracted trained teachers with better pay and living conditions. In Kentucky, firms such as the Stearns Coal and Lumber Co., provided schools at their own expense in company towns. [60]

Railroads, Investors, and Tourists

Arrive

During the 1880's and 1890's, a series of developments began almost imperceptibly to alter the economic and social life of the Southern Appalachians. Railroads, which before the 1880's had just skirted the mountains on their way West, finally crossed the big hurdle of the Blue Ridge, after much difficulty, and the region was "discovered" by outsiders—tourists, health-seekers, journalists, novelists, and investors. A line reached Asheville from Winston-Salem and Raleigh in 1880, and then went over the Great Smokies to Knoxville. [61] As railroad construction accelerated, and as more northerners became familiar with the area, the resources of the region drew increasing national attention. The tremendous industrial expansion and urban growth that the northeastern and north central United States experienced after the Civil War created heavy demand for raw materials, particularly timber and coal. Sources of these materials that had previously been inaccessible or even unknown grew attractive to investors. By 1900, northern and foreign capital was invested in even the remotest areas, as the region was pulled into the national urban-industrial system.

In the last decade of the century the Southern Railway extended lines into northern Georgia, reaching the heavily wooded slopes that would one day be included in the Chattahoochee National Forest. [62] In the early 1880's the Norfolk and Western Railroad extended lines into southwestern Virginia, principally to tap the wealth of coal in Tazewell County. A branch down the Clinch River Valley opened up the coal fields of Wise County. In 1890 this line was linked to Knoxville by the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. [63] In 1901 the Southern Railway joined the area of Brevard and Hendersonville, near Asheville, to its system. [64] The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad consolidated lines in eastern Kentucky after 1900, linking Cairo, Ill., with Cumberland Gap. [65] Some mountain areas, however, remained unconnected by rail. Most of the northwestern North Carolina was reached late by railroad. Not until 1917 did a rail line arrive in Boone, seat of Watauga County. [66] But by 1910, a rail network was well established in the Southern Appalachians.

Well before the railroads, the mountains had been a mecca, however. As early as the 1820's, wealthy Charlestonians traveled by carriage to spend summers in the mountains, particularly at mineral springs. Several prominent South Carolinians built summer homes in the Cashiers area of southwestern North Carolina before the Civil War. Resort hotels were established throughout the region, notably in Asheville, White Sulphur Springs, and Hot Springs, N.C., which were interconnected by stage coach lines. In 1877 a log lodge was built on the 6,150-foot crest of Roan Mountain, in Mitchell County, N.C., bordering Carter County, Tenn. More elaborate ones followed.

Early Tourist Boom

With the railroads, tourism boomed, albeit highly localized and seasonal. Nowhere was the boom so evident as in Asheville. From 2,600 residents in 1880, it grew fivefold in 10 years. The town thrived first as a haven for tuberculosis patients; its many sanitaria included the well-known Mountain Sanitarium. [67] Notable among numerous hotels were the large, luxurious Battery Park Hotel, built shortly after the railroad arrived, and the Grove Park Inn, built in 1913. The city soon became a favorite resort for wealthy and middle-class businessmen from the industrial Northeast. The town bustled in the summer with crowds of tourists; in 1888 Charles Warner, New York journalist, praised its gay atmosphere and facilities highly. [68]

Many who were attracted to Asheville as tourists became residents. Wealthy families, like the George Vanderbilts of New York and the Vances of North Carolina, built lavish mountain estates nearby. The English financier, George Moore, created a hunting preserve in the Great Smokies in Graham County, N.C., which he stocked with bears and wild boars to provide sport for his guests. Meanwhile, resorts and hotels proliferated. After the railroad was extended to Knoxville, the large hotel at Warm Springs added 100 rooms. Investors constructed a resort town at Highlands, Macon County, N.C., which in 1890 had 350 inhabitants and was attracting tourists from coastal South Carolina and Georgia. Carl A. Schenck, a German forester who taught forestry on the Biltmore estate near Asheville, noted that, in about 1901, a "modern hotel" was built even in the small town of Brevard, Transylvania County, N.C., "where rooms with real baths were obtainable." [69]

Tourists spread word of the resources and increasing accessibility of the region. State resource surveys of the 1880's and 1890's publicized it. In 1891 the North Carolina Geological Survey examined the State's resources in an effort to further economic development. Foresters W. W. Ashe and Gifford Pinchot, who later became Chief of the Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, were hired to conduct the forest survey. This survey and others like it confirmed the observations of tourists and helped induce investments in timber, coal, and other minerals worth millions of dollars. [70]

Mountaineer Stereotype Develops

As the railroads opened up portions of the mountains and resort areas sprang up, the region attracted novelists and journalists in search of local color. During the last 30 years of the 19th century, travelogues and short stories set in little-known locales were extremely popular with the national reading public. Major magazines of the period—Lippencott's, Harper's, Scribner's, and Appleton's—provided a ready market for such writing. Professional authors looking for a romantic setting and for dramatic, novel materials found both in the Southern Appalachians.

Writers who popularized the region generally focused on the mountains of one State. For example, Mary N. Murfree, under the pseudonym Charles E. Craddock, wrote numerous stories such as "The Romance of Sunrise Rock" and "The Despot of Broomsedge Cove," most set in the Great Smoky Mountains of eastern Tennessee. The background of Frances H. Burnett's stories was North Carolina. James L. Allen wrote extensively of travels through the Cumberland area of Kentucky. Such writings found a wide audience; the most popular stories and articles were printed both in magazine and book form, and books often went through several editions. [71]

These authors pictured a culture different from the rest of America, especially the urban middle-class reader. The mountain environment was described as mysterious and awesome, and the mountaineer as peculiar and antiquated, with customs and a language of his own.

Along with northern journalists came the northern Protestant home mission movement. Protestant missionary work in the mountains grew out of a general effort to transform the South along northern lines and to eliminate racial discrimination through education and religious influence. At a time when the major older Protestant denominations were competing for new mission fields to develop, the Southern mountains were seen by many as an "unchurched" land, despite the numerous small Baptist congregations, because these northern Protestant denominations were weakly represented there. To overcome this situation, several hundred church schools were established throughout the region, supported by the American Missionary Association. One of the best known private Christian schools in Appalachia is Berea College in Berea, Ky., founded in 1855 by John S. Fee, a Presbyterian (later a Baptist) minister, as an integrated, coeducational, but nondenominational institution. These schools emphasized what they saw to be Christian and American values, modern ways, and provided practical training for the "exceptional population" of the region to participate fully in national life. Henry Shapiro claims that mission schools institutionalized Appalachian "otherness," through the implicit insistence that the mountaineers did in fact compose a distinct element in the American population." [72]

By the end of the 19th century, the southern mountaineer had been identified by others as not only different from most Americans but also in need of their help. Two aspects of mountain behavior in particular captured the interest of outsiders. These were the sometimes-linked practices of moonshining and feuding. Mountaineers came to be perceived and characterized as illegal distillers of corn whiskey and as gun slingers who fiercely protected their stills, their homesteads, and their family honor with little regard for the law. [73]

Estimating the actual prevalence of moonshining and feuding in 19th century Southern Appalachia is difficult at best, for from the beginning the documentation of these practices was unscientific. Certainly, moonshining was a common household industry. During the Civil War, distilleries were required to be licensed, and liquor was taxed at increasingly higher rates (from 20 cents per gallon in 1862 to $2.00 per gallon in 1864). Although a certain degree of compliance with these regulations occurred, many mountaineers resented the Government's authority to take a large cut of one of the few profits they could realize from their labors. They simply defied the system by hiding their stills in the woods, literally making whiskey by moonshine, and selling the liquor on the sly. [74]

After the Civil War, as the liquor tax increased but the revenues from it decreased, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service established new penalties for tax violations and instituted an era of raids on illegal mountain stills. Although moonshiners often established secret cooperative relationships with Federal revenuers (perhaps proferring their wares in exchange for Government oversight of their stills), they generally evaded the Federal agents or challenged them. As Carl Schenck, the German forester, wrote of the late 19th-century moonshiners in western North Carolina, liquor distilleries were hidden in the mountain coves and were "shifted . . . from site to site to avoid discovery." Moonshiners "went about armed, keeping the others in awe and threatening death to any betrayer of their secrets." Federal raids sometimes resulted in bloodshed. Violence was often the penalty for informers and the outcome of discovery of an illegal still. [75]

Family Feuds

The common denominator of bloodshed linked moonshining and feuding in the minds of Appalachian observers. Although in fact the two were sometimes related, feuding stemmed from broader and more basic causes. Feuding has been interpreted by some to have developed from the interfamilial disputes of the Civil War that occurred in and around the Southern Appalachians. Major campaigns and battles took place at Knoxville and Chattanooga, and numerous mountain gaps provided significant passage for both Union and Confederate troops. In John Campbell's words, "the roughness of the country led to a sort of border guerrilla warfare." Throughout the region, mountaineers joined both the Union and Confederate armies, with family members often on opposite sides. Such divisions provoked bitter local hostilities and provided the seeds for lasting feuds. In Madison County, N.C., Union sympathizers "seized the town of Marshall, plundered the stores and committed many acts of violence." In retaliation, a thousand Confederate sympathizers from nearby Buncombe County engaged them in a punishing skirmish. After the war, as political parties developed along lines of Union-Confederate sympathies, such acrimony continued not only as interfamilial feuds, but as partisan rivalry as well. [76]

The most notorious of feuds was that between the Hatfield family of Tug Valley, W.Va., and the McCoys of Pike County, Ky. Beginning in the early 1880's with a series of minor misunderstandings, the feud quickly escalated into violence. Members of each family kidnapped, ambushed, and killed members of the other family with avenging spirit throughout the decade. Both Governor MacCorkle of West Virginia and Governor Bucknew of Kentucky tried to intervene by strengthening law enforcement in the area. The feud continued sporadically until about 1920 when Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield, the family patriarch, died of pneumonia. [77]

By the end of the 19th century, outsiders were seeking not only to describe and to change the mountaineer, but also to explain his quaint, peculiar, and sometimes disturbing behavior. Such explanations perpetuated and even enhanced the mountaineer stereotype. Geographical determinism and ethnic origin were most generally accepted as explanations. In 1901, a geographer, Ellen Churchill Semple, in a study of the mountain people of Kentucky, emphasized the Scotch-Irish heritage of the mountaineer and described his behavior as a pattern of adjustments required by the rugged and isolated mountain environment. He was soon widely perceived to be a remnant of pioneer days, a man of pure Anglo-Saxon stock whose culture had been isolated and been preserved by the rugged terrain and inaccessibility of the mountains. [78]

Moonshining and feuding, as examples of mountaineer behavior left over from frontier days, symbolized the independence and lawlessness of the pioneer. Mountain feuding was explained by identifying the mountaineers as Highlanders and relating the feuds to Scottish clan warfare, an idea deriving from James Craighead's Scotch and Irish Seeds in American Soil, an 1878 publication popularized by the American Missionary Association. Later, John Campbell attributed both moonshining and feuding to the mountaineer's high degree of individualism: "His dominant trait is independence raised to the fourth power." Geographer Rupert Vance emphasized environmental adaptation as an explanation of moonshining and feuds: "Stimuli to homicide were many where lands were settled by the squatter process and titles were so obscure." [79]

An alternative view of the mountaineer that developed early was also based on ethnicity. John Fiske, a popular historian of the late 19th century, gave currency to the false idea that virtually all Southern mountaineers were descendants of whites transported to America as servants or criminals in early colonial times. [80] Such a distorted, ignorant view of the mountaineer as Anglo-Saxon criminal made it easier for some to see why feuding and illegal distilling persisted in spite of Christian education and increased law enforcement. This naive view, which was repeated and reinforced in the 20th century by the writing of John Gunther and Arthur Toynbee, achieved a modern stridency in the words of Kentuckian Harry Caudill. Caudill claimed the mountaineer was "the illiterate son of illiterate ancestors," and of debtors, thieves, and orphans who fled the cities of England:

. . . cast loose in an immense wilderness without basic mechanical or agricultural skills, without the refining, comforting, and disciplining influence of an organized religious order, in a vast land wholly unrestrained by social organization or effective laws, compelled to acquire skills quickly in order to survive, and with a Stone Age savage as his principal teacher. [81]

Investors Transform the Region

The railroads opened the area to investors as well. Some of the investors were northern financiers; some were British investment capitalists whose interest in the region was but a small part of their overseas investments. A few of the capitalists came to the region to stay as did Joseph Silverstein of New York who formed the Gloucester Lumber Co. southwest of Asheville, and Reuben B. Robertson of Canton, Ohio, who managed the Champion Fibre Co. of North Carolina. Most, however, invested in the region only to extract the desired riches, and then withdrew.

The foreign investment and industrial development which followed was frequently hailed as a natural solution to "a whole range of problems . . . resulting from the isolation of Appalachia and the poverty of the mountaineers." [82] Much of the capital investment in the Southern mountains between 1880 and 1900 was justified by a belief that economic development and industrialization were best for the region itself.

The impact this industrial investment was to have on the people of the Southern Appalachians was profound. By 1900 the isolated, self-contained farming existence that had characterized the region was quickly changing and, by 1920, was seriously disrupted. Before 1880, the southern mountaineer made his living directly from the land, and needed only modest amounts of cash, which he could raise from the sale of livestock, trees, or other products from his land. From 1890 on, the timber and coal companies purchased much of the mountaineer's land, gave him a job in a mill, mine, or factory, paid him in cash, brought in canned food and consumer goods for him to buy, and educated him in the ways of the modern world. Industrialization, urbanization, large-scale changes in landownership and land use, as well as deliberate attempts to change the society and culture of the mountaineer, had come to the Southern Appalachians to stay. Two world wars, the Great Depression, the New Deal social programs, TVA, and the introduction of the Federal forest and parks also had major lasting impacts on the area and its people.

Reference Notes

1. 36 Stat. 962 (16 U S C 515, 521); 43 Stat. 653 (16 U.S.C. 471, 505, 515, 564-70).

2. For general discussions of the alternative definitions of the Southern Appalachian region, see Bruce Ergood, "Toward A Definition of Appalachia" in Bruce Ergood and Bruce Kuhre (eds.), Appalachia: Social Context Past and Present (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University, 1976), pp. 31-41 and Allen Batteau, "Appalachia and the Concept of Culture: A Theory of Shared Misunderstandings," Appalachian Journal 7 (Autumn/Winter, 1979-80): 21, 22.

3. John Campbell, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland (Lexington: The University of Kentucky Press, 1969), pp. 10-13. Campbell distinguishes a Southern Appalachian region as that part of the Southern Highlands which is south of the New River divide, p. 12.

4. Thomas R. Ford (ed.), The Southern Appalachian Region: A Survey (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1962).

5. Map published by the Appalachian Regional Commission, January, 1974. The Commission has divided "Appalachia" into Northern, Central, and Southern subregions. Within each of these, there is a "Highlands Area," representing the most mountainous counties of the region.

6. Wilbur Zelinsky, The Cultural Geography of the United States (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1973), p. 112.

7. Helen M. Lewis, "Subcultures of the Southern Appalachians," The Virginia Geographer (Spring 1968):2.

8. Batteau, "Appalachia and the Concept of Culture: A Theory of Shared Misunderstandings":29.

9. This geographic focus includes all the Appalachian National Forests within the Forest Service's Southern Region (R-8), with the exception of the George Washington National Forest. Because it is located north of the New River divide and within a 90-minute drive of Washington, D.C., the George Washington National Forest was felt to belong more properly with a consideration of the Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia, the Allegheny in Pennsylvania and Wayne National Forest in Ohio.

10. 36 Stat. 962; 43 Stat. 653.

11. Some 61,500 acres were purchased for the Blue Ridge Parkway and over 507,000 for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Almost 3.5 million acres have been acquired for the Nantahala, Pisgah, Cherokee, Chattahoochee, Daniel Boone, and Jefferson National Forests.

12. Si Kahn, "The National Forests and Appalachia," Cut Cane Associates, 1973, p. 1.

13. Charlton Ogburn, The Southern Appalachians: A Wilderness Quest (New York: William Morrow and Co., 1975), pp. 67-72; and Frederick A. Cook, Larry D. Brown, and Jack E. Oliver, "The Southern Appalachians and the Growth of Continents," Scientific American 243 (October 1980): 156-169.

14. The three subregions have also been labeled "belts" or "provinces" and have received varying names. The Valley and Ridge subregion for example, has been called The Greater Appalachian Valley, The Newer Appalachians, and The Folded Appalachians. For physiographic descriptions of the three subregions, see John C. Campbell, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland, pp. 10-18; Edgar Bingham, "Appalachia: Underdeveloped, Overdeveloped, or Wrongly Developed?" The Virginia Geographer VII (Winter 1972): 9; Wallace W. Atwood, The Physiographic Provinces of North America (Boston: Ginn and Company, 1940), pp. 109-122; Charles B. Hunt, National Regions of the United States and Canada (San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Co., 1974), pp. 282-299; Thomas R. Ford (ed.), The Southern Appalachian Region: A Survey, pp. 1-3; and Rupert B. Vance, Human Geography of the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1932), pp. 27, 28.

15. Atwood, The Physiographic Provinces, p. 14.

16. The subregion has also been likened to "a wrinkled rug." Cook, et. al., "The Southern Appalachians," p. 160.

17. Ogburn, The Southern Appalachians, p. 103.

18. One explanation for the reversal is that, north of Roanoke, the sea advanced and retreated several times over millions of years and, in so doing, created a new drainage pattern. See Atwood, The Physiographic Provinces, p. 120.

19. Hunt, Natural Regions, pp. 287, 288.

20. Ogburn, The Southern Appalachians, 151-171; Ina W. VanNoppen and John J. VanNoppen, Western North Carolina Since the Civil War (Boone: Appalachian Consortium Press, 1973), p. 291.

21. Ogburn, The Southern Appalachians, pp. 139-150.

22. Campbell, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland, pp. 246, 247

23. Hunt, Natural Regions, pp. 297-299.

24. Cook, et. al., "The Southern Appalachians."

25. Roy S. Dickens, Jr., Cherokee Prehistory: The Pisgah Phase in the Appalachian Summit Region (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976), pp. 9-15; and Ogburn, The Southern Appalachians, p. 55.

26. Ogburn, The Southern Appalachians, pp. 10, 11. David S. Walls, in "On the Naming of Appalachia," maintains that DeSoto's discovery of the Appalachians is merely "legend" and that the first European to designate the mountains by their names was Jacques le Moyne de Morgues, a Frenchman, in 1564. J.W. Williamson (ed.), An Appalachian Symposium (Boone: Appalachian State University Press, 1977), pp. 56-76.

27. Frederick Jackson Turner, Rise of the New West, 1819-1829 (New York: Collier Books, 1962), pp. 56-58.

28. Descriptions of the pioneer settlement of the Southern Appalachians are found in Campbell, The Southern Highlander, pp. 23-42; John Caruso, The Appalachian Frontier: America's First Surge Westward (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Co., Inc., 1959); Vance, Human Geography of the South; and Harry Caudill, Night Comes to the Cumberlands (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1962).

29. Campbell, The Southern Highlander, p. 42.

30. Turner, Rise of the New West, pp. 84-86.

31. Dickens, Cherokee Prehistory, pp. 14, 15.

32. Ogburn, The Southern Appalachians, pp. 55-58. See also Kenneth B. Pomeroy and James G. Yoho, North Carolina Lands: Ownership, Use, and Management of Forest and Related Lands (Washington: The American Forestry Association, 1964), pp. 92-120; and Duane H. King (ed.), The Cherokee Indian Nation (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1979).

33. VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, p. 379. Campbell, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland, p. 33.

34. Ronald D. Eller, "Land and Family: An Historical View of Preindustrial Appalachia," Appalachian Journal 6 (Winter 1979): 84, 86.

35. Ronald D. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers: The Modernization of the Appalachian South, 1880-1930" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina, 1979), p. 23.

36. VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, pp. 2, 3. Gene Wilhelm, "Folk Geography of the Blue Ridge Mountains," Pioneer America (1970): 1, 2.

37. Eller, "Land and Family," p. 85. Eller, "Mountaineers, Miners, and Millhands," p. 20.

38. This and the following demographic description of the Southern Appalachians is based on Bureau of the Census data for 79 mountain counties which represent the core of the region. These counties include:

| Georgia: | Banks, Catoosa, Chattooga, Fannin, Gilmer, Gordon, Habersham, Lumpkin, Murray, Rabun, Stephens, Towns, Union, Walker, White, Whitfield; |

| Kentucky: | Bath, Bell, Clay, Estill, Harlan, Jackson, Knott, Knox, Laurel, Lee, Leslie, Letcher, Menifee, Morgan, Perry, Powell, Pulaski, Rockcastle, Rowan, Whitley, Wolfe; |

| North Carolina: | Avery, Buncombe, Burke, Caldwell, Cherokee, Clay, Graham, Haywood, Jackson, Macon, McDowell, Madison, Mitchell, Swain, Transylvania, Watauga, Yancey; |

| Tennessee: | Blount, Carter, Cocke, Greene, Johnson, McMinn, Monroe, Polk, Sevier, Sullivan, Unicoi, Washington; |

| Virginia: | Bland, Dickenson, Giles, Grayson, Lee, Pulaski, Russell, Scott, Smythe, Tazewell, Washington, Wise, Wythe. |

Data comes from Bureau of the Census, Twelfth Census of U.S. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902).

39. For a full discussion of Middlesboro's founding, see Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," pp. 130-137.

42. Vance, Human Geography of the South, p. 247. Gene Wilhelm, Jr., "Appalachian Isolation: Fact or Fiction?" in J. W. Williamson (ed.), An Appalachian Symposium (Boone: Appalachian State University Press, 1977), p. 88.

43. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," p. 36, 37; and Jack E. Weller, Yesterday's People (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1966), pp. 12, 13.

44. Weller, Yesterday's People, 38-40.

45. Frank L. Owsley, Plain Folk of the Old South (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1965), p. 45.

46. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," pp. 40-42; Susie Blaylock McDaniel, Official History of Catoosa County, Georgia 1853-1953 (Dalton, Georgia: Gregory Printing and Office Supply, 1953), p. 195; Goodridge Wilson, Smythe County History and Traditions (Kingsport, Tennessee: Kingsport Press, 1932), p. 171; and Wilhelm, "Appalachian Isolation," p. 83.

47. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," p. 43; and George L. Hicks, Appalachian Valley (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winson, 1976), pp. 20, 21.

48. Wilhelm, "Appalachian Isolation," p. 88; and Vance, Human Geography of the South, p. 249.

49. VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, pp. 276, 277.

50. Wilhelm, "Appalachian Isolation," p. 83.

51. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," p. 26.

52. VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, p. 18.

53. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," p. 29.

54. Campbell, The Southern Highlander, p. 102.

55. VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, p. 27.

56. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," p. 65, and Laurel Shackelford and Bill Weinberg, eds., Our Appalachia (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), pp. 23-25.

57. Willis D. Weatherford, ed., Religion in the Appalachian Mountains: A Symposium (Berea, Ky.: Berea College, 1955), pp. 35-50.

58. Campbell, The Southern Highlander, pp. 170, 171; and VanNoppen and VanNoppen Western North Carolina, p. 72.

59. Weatherford, Religion in the Appalachian Mountains, pp. 96-98, and Shackelford and Weinberg, Our Appalachia, pp. 44-50.

60. Campbell, The Southern Highlander, p. 264; L. E. Perry, McCreary Conquest, A Narrative History (Whitley City, Ky.: L. E. Perry, 1979), pp. 63-72.

61. Wilma Dykeman, The French Broad (New York: Rinehart and Company, 1955), p. 164. See pp. 159-165 for colorful description of Western North Carolina Railroad construction. See also VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, pp. 253-259.

62. Ignatz Pikl, A History of Georgia Forestry (Athens: University of Georgia, Bureau of Business and Economic Research, 1966), p. 9.

63. Eller, "Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers," pp. 114-129.

64. Carl Alwin Schenck, The Birth of Forestry in America (Santa Cruz, Calif.: Forest History Society and the Appalachian Consortium, 1974), p. 103.

65. William Haney, The Mountain People of Kentucky (Cincinnati: The Robert Clarke Company, 1906), p. 94.

66. VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, p. 265.

67. Ogburn, The Southern Appalachians, pp. 18, 19; VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, pp. 40, 378, 379.

68. Charles Dudley Warner, On Horseback: A Tour in Virginia, North Carolina and Tennessee (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1888), p. 111, 112.

69. Alberta Brewer and Carson Brewer, Valley So Wild: A Folk History (Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1975), pp. 131-133. VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, p. 260, p. 378; Schenck, Birth of Forestry in America, p. 103.

70. John R. Ross, "Conservation and Economy: The North Carolina Geological Survey, 1891-1920," Forest History 16 (January 1973): 21; and Judge Watson, "The Economic and Cultural Development of Eastern Kentucky from 1900 to the Present" (Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, 1963), p. 42.

71. The major source for material on the discovery of the Southern Appalachians and the development of the mountaineer stereotype is Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind. For mention of writers, see pp. 310-339.

72. Henry D. Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind, 32, 42.

73. Henry D. Shapiro, "Appalachia and the Idea of America: The Problem of the Persisting Frontier," in Williamson, An Appalachian Symposium, pp. 43-55.

74. Esther Kellner, Moonshine: Its History and Folklore (New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1971), p. 78; VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, pp. 273, 274. A description of legal distilling in Kentucky occurs in Shackelford and Weinberg, eds., Our Appalachia, pp. 102-108.

75. Schenck, Birth of Forestry in America, p. 64; George W. Atkinson, After The Moonshiners (Wheeling, W. Va.: Frew, Campbell, Stearn Book and Job Printers, 1881).

76. Campbell, The Southern Highlanders and Their Homeland, p. 97; VanNoppen and VanNoppen, Western North Carolina, pp. 15-17.

77. Otis K. Rice, The Hatfields and the McCoys (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1978); and Lawrence D. Hatfield, The True Story of the Hatfield and McCoy Feud (Charleston: Jarrett Printing Company, 1944). Shackelford and Weinberg, eds., Our Appalachia, p. 60.

78. Ellen Churchill Semple, "The Anglo-Saxons of the Kentucky Mountains: A Study in Anthropogeography," Geographical Journal 17 (June 1901): 588-623. Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind, Chapter 3.

79. James G. Craighead, Scotch and Irish Seeds in American Soil (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1878). Campbell, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland, p. 91. Vance, Human Geography of the South, p. 250.

80. John Fiske, Old Virginia and Her Neighbors, II (Boston: Houghton Mifflin and Co., 1897), pp. 311-321.

81. Caudill, Night Comes to the Cumberlands, p. 17; W. K. McNeil, "The Eastern Kentucky Mountaineer: An External and Internal View of History," Mid-South Folklore (Summer, 1973): 36.

82. Shapiro, Appalachia On Our Mind, p. 158.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region8/history/intro.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2008