|

Senate Document 84 Message from the President of the United States Transmitting A Report of the Secretary of Agriculture in Relation to the Forests, Rivers, and Mountains of the Southern Appalachian Region |

|

APPENDIX A. (continued)

By H. B. AYRES and W. W. ASHE.

|

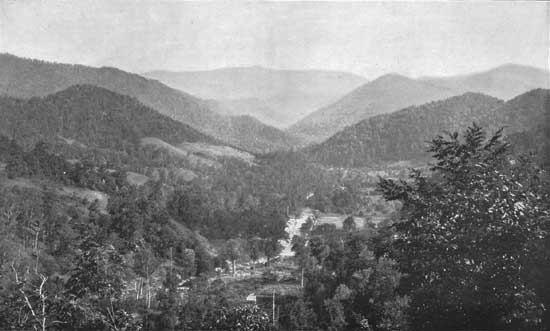

The Southern Appalachian Mountains extend from Virginia southwestward into Alabama, and lie between the Piedmont Plateau on the southeast and the lowlands of East Tennessee on the northwest. That this is preeminently a region of mountains is well illustrated by the fact that the mountain slopes occupy 90 per cent of the total area; and probably the combined area of the valleys and gentler slopes (of less than 10 degrees—about 2 feet in 10) will not aggregate more than 15 per cent of the whole. | |||||

|

Entire mountain region originally forest covered with forest. |

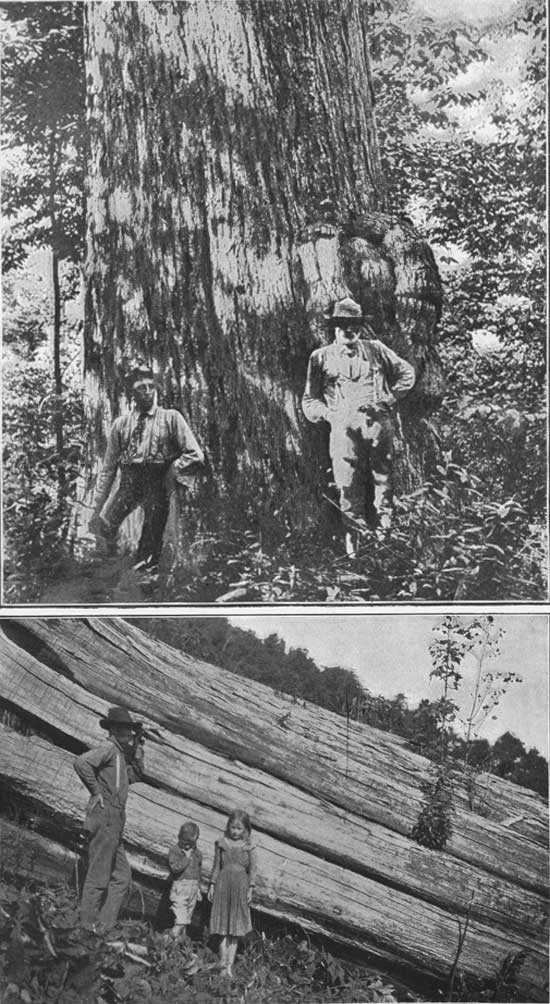

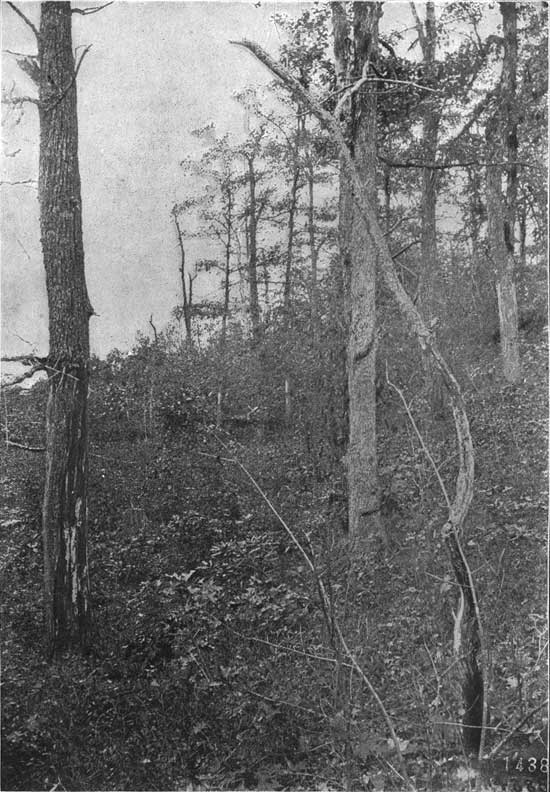

Before the advent of man the entire region, save the tops of a few high mountains—the grassy "balds"—was covered with forest, mainly hard wood. (See Pl. XXXVII.) Then, as now, the forest varied as to density and vigor of growth, but a far larger portion of that existing then is resembled by the best of to-day on such tracts as are found in the most favored situations and have been protected from fire and severe culling. | ||||

| |||||

|

Nature and extent of the clearings. |

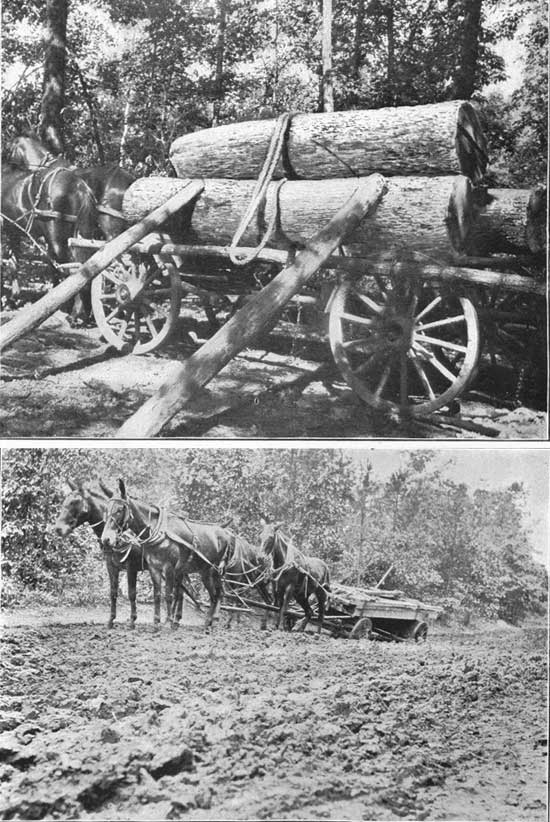

A total area of 5,400,000 acres has been examined in connection with this investigation, and of this 4,050,000 acres, or 75 per cent of the whole, are still in forest. Of this total area in forest about 7.4 per cent, or 303,000 acres, is still in primeval condition, i. e., has never been culled at all. The remainder of this wooded area has been culled to a varying extent. (See Pl. XXXVIII.) A limited portion of that near the railway lines has been robbed of nearly everything of commercial value, while the remote areas have had only the walnut, cherry, and figured woods cut. From the intervening areas, far the larger part of the whole, a varying proportion of the most valuable trees have been removed, but large amounts of commercial timber still remain. The clearing and culling of a century have made considerable inroads into these forests. The woodland connected with the farms has been largely culled and is in part covered with trees of second growth. In many places, where transportation facilities are available, the mills have gone into the heart of the mountain region and much of the choicest timber has been sawed there and hauled on wagons to the railroad. (See Pl. XXXIX.) | ||||

| |||||

|

General character of the forests. |

As to composition, generally speaking, it may be said that the forest below the 2,000-foot elevation consists of oaks, hickories, and pines; above that elevation are many hard woods, or hard woods associated with hemlock and white pine. Some spruce and balsam occur on the cold north slopes and around the tops of the larger and higher mountains.

| ||||

|

Subdivision of forest area. |

For the sake of convenience in description the forest area may be subdivided as follows: (1) The forests of the Blue Ridge. (2) The forests of the White Top Mountain group. (3) The forests of Roan, Grandfather, and Black mountains. (4) The forests of the central interior mountain ridges. (5) The forests of the Great Smoky Mountains. (6) The forests of the southern end of the Appalachians. FORESTS OF THE BLUE RIDGE. The Blue Ridge from Virginia to Georgia is, on the dryer slopes and crests, lightly timbered with small oaks, chestnut, and pines, while in the hollows mixed hard woods—oaks, chestnut, hickories, etc.—form heavy timber. The forests are on the ridges and steeper slopes. The narrow alluvial bottoms and often portions of the adjoining slopes have been cleared and are under cultivation or have been abandoned. But excepting these cleared valleys and hillsides, the forests are almost continuous from Virginia to Georgia. While the hardwood forests have been culled along nearly the entire east slope, only the choicest trees of the lighter woods, among which are white pine, have been cut. (See Pl. XXXVIII a.) Before any of it was cut the white pine on the Linville River was probably the finest in the Southern mountains. A great part of this has been removed. It is being transported on a narrow-gauge railway via Cranberry to Johnson City. Mills at Hickory and Lenoir are cutting the pine in the Johns River Valley. The other smaller bodies of white pine have been culled of their finest trees. FOREST OF THE WHITE TOP MOUNTAIN REGION. This region embraces the northwestern corner of North Carolina, the northeastern corner of Tennessee, and the adjacent portion of southwestern Virginia. In this portion of the Appalachians, the Unaka (here represented by Iron Mountain) and the Blue Ridge ranges approach nearer each other, and the intermediate land retains more of its original character as a plateau lying between the great Appalachian Valley, drained by the Tennessee River, on the northwest, and the Piedmont Plateau on the southeast. The White Top group comprises the mountains along the northern rim of the elevated mountain region. | ||||

|

Topographic features. |

To the irregular mountain ridge which in this more northern region forms the boundary line between North Carolina and Tennessee, the name of Stone Mountain is applied. Here and there this ridge rises into peaks of prominence. On one of these, Pond Mountain, which has an elevation of 5,100 feet, the boundary lines between North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia corner. Another of these, White Top Mountain, some 5 miles to the northeast, and a far more massive and imposing mountain, rises to an elevation of 5,678 feet. Still another, Mount Rogers, on the Balsam Ridge, about 5 miles a little north of east from the White Top, rises to an elevation of 5,719 feet. The general course of this Stone Mountain ridge is to the northeast as far as Mount Rogers and then continues eastward as Iron Mountain to New River Gap. Northwest of it, in Tennessee, is another less regular and less prominent ridge known as the Iron Mountains, reaching an elevation at intervals of from 3,000 to 4,000 feet; and 6 to 8 miles to the west of this latter, in Tennessee, is the Holston Mountain ridge, reaching a still higher elevation. These ridges are all approximately parallel, having in East Tennessee a general northeasterly course. To the northwest of these mountains lies the broad, fertile valley of the South Holston; to the southeast is the more elevated valley of New River, broken into an endless series of steep, round-crested hills, mostly cleared, and producing well in both grass and grain. Broad agricultural valleys lie between the Iron and Stone mountains and between the Iron and the Holston mountains. There are many farms on the southeastern slope of the Stone Mountain, and its northwestern slope is dotted with clearings. Extensive clearings cover the southern foot hills of both White Top and the Balsam mountains. There is, however, in this group an almost unbroken forest, at least 6 miles in width, extending along the mountains from Elizabethton east to Mount Ewing, a distance of more than 60 miles. | ||||

|

Extensive mountain forests. |

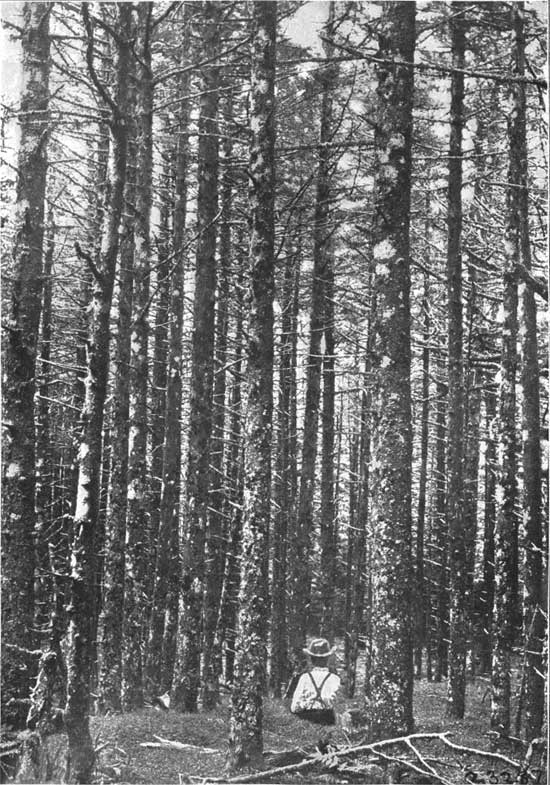

The portion of this forest to the southwest of Damascus covers the slopes of the Iron and Holston mountains and much of Shady Valley, between them. It is largely composed of hard wood, with which white pine and hemlock are associated. For 8 miles east of Damascus the forest covers both slopes of Iron Mountain. It has been slightly culled, but much burned. It is lightly timbered with oak, chestnut, hemlock, and some white pine. A large area lying east of White Top Mountain, on the upper slope of the Balsam Mountains, is heavily timbered with spruce (see Pl. XL) on and near the summits, while hard woods, with some hemlock intermixed, occupy the lower elevations. From the eastern end of the Balsam Mountains the Iron Mountain extends almost eastward to Mount Ewing, a distance of 40 miles. Its summit is dotted with a few farms and pastures, but the forest on the slopes is almost unbroken. It is lightly timbered with small oaks, chestnut, hickories, and black pine. The forest has been severely burned over large areas. A railroad has been built from Damascus southwestward through Shady Valley, and some of the finest white-pine timber in the United States is now being cut there. (See Pl. XXXVIII b.) South of this large belt of forest are a few isolated mountains in the midst of the agricultural valley of New River which have their slopes well timbered. The largest of these are Phoenix, Three Top, and Elk mountains, which lie between the north and south forks of New River. Nearly 40,000 acres of this forest is unculled. There are six holdings of 10,000 to 50,000 acres each; the remainder is held in small areas of a few hundred acres. The farming region of both the New and Holston river valleys is dotted with wood lots sufficient to supply the needs of the resident population. | ||||

| |||||

|

|

FORESTS OF ROAN, GRANDFATHER, AND THE BLACK MOUNTAINS. Roan Mountain stands as a prominent figure in this group of four similar large, isolated mountain masses—Beech, Grandfather, Roan, and Black mountains—in a region which is largely devoted to agriculture. These mountains are alike in the general character of the forests on their slopes, and the agricultural lands about their foothills and intervening valleys. They are all heavily timbered, and, though much of their forest has been partially lumbered, only occasional choice trees have been cut, causing no break in the forest and little change in its condition. Mixed hardwoods form the dominant element, and associated with them are small areas of hemlock. Limited areas of spruce are found on or near their tops. Beech Mountain is the lowest of these four. It has few coniferous trees about it except hemlock and white pine on its northern slope, while large areas on the summits of Grandfather, Roan, Black, and Craggy mountains are occupied by spruce and balsam forests. These forests are virtually primeval, and trees of all sizes and ages are found intermingled, showing abundant reproduction and an undisturbed forest equilibrium. Along the drier portions of the summits and the ridges leading up to them, especially on the south slopes, fires have in some places done considerable damage. But areas entirely fire killed are small. | ||||

|

Forests and topographic features about Beech Mountain. |

(1) The Beech Mountain group, including Sugar Mountain and other smaller peaks near it, lies between Watauga River and Banners Elk Creek and is the most northerly group. It has an area of about 70,000 acres (110 square miles), 20,000 acres (32 square miles) or about 30 per cent of which are cleared. It is the lowest of the four groups, having an altitude of only 5,522 feet. It is separated from Grandfather Mountain, which is about 15 miles southeast of its summit, by the valley of the Watauga River and from Roan Mountain, which is about the same distance to the southwest, by the valley of Elk Creek, which is partly cleared. Although the south slope of the mountain is steep, the soil is deep and mellow and grass farms extend nearly to the summit. There are also a few farms on the northern slopes. The original forests of Beech Mountain are now largely confined to the deep hollows on the northern slopes. The greater part of them have been culled in degrees varying with their ease of access. | ||||

|

Forests and topographic features about the Grandfather Mountain. |

(2) The Grandfather Mountain group, including Grandfather and Grandmother mountains, lies on the Blue Ridge, and is the highest point in that range, having an altitude of 5,964 feet. While it is situated on the Blue Ridge, its affinities, so far as its forests are concerned, are with the interior mountain areas and not with the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge. The agricultural lands of this region lie to the north of the Grandfather along New and Watauga rivers, to the west in the valley of North Toe River, and on the low mountains and round hills, dotted with clearings, lying between the Grandfather and Roan groups. This mountain group contains an area of more than 100,000 acres, only a small portion of which is cleared. The cleared land is located chiefly among the headwaters of Linville and Watauga rivers. The topography of the entire group is rough, with steep and often rocky slopes. Many of the farms are on land which is too steep for profitable agricultural use. The eastern and southern slopes of the mountains are lightly timbered. The western and northern slopes have been somewhat culled, but are still heavily wooded. A dense mixed forest covers the northern slope and extends across the valley of Boone Fork of Watauga River, which is yet uncleared for a distance of more than 5 miles from its head. (3) The Roan Mountain group, including Roan Mountain, Yellow Mountain, and Spear Top, lies on the boundary line between North Carolina and Tennessee, between Doe and Toe rivers. It rises from a base of 2,000 feet to a height of 6,313 feet. The area of this group is about 120,000 acres, over one-fourth of which, or 35,000 acres, is cleared. The slopes are slightly more gentle than on any other of the large mountains, and are well wooded, though dotted with clearings. The entire wooded portion of this area is well timbered. The north slope, being nearest to the railroad, has been more culled, but some timber has also been cut on the south slopes at the heads of Big and Little Rock creeks. | ||||

|

Forests and topography about the Black Mountains and the Craggies. |

(4) The Black Mountains, which lie just west of the Blue Ridge, a few miles north of where the latter range is crossed by the Southern Railway, are a series of short ridges. The most massive of these is that of Black Mountain proper, which diverges from the Blue Ridge and extends northward 10 miles to a rather abrupt ending. The larger part of this ridge rises above 6,000 feet, and Mount Mitchell, the highest of half a dozen grand peaks, reaches an elevation of 6,711 feet. From near the southern end of the Blacks the Craggy Mountain ridge extends southwestward for a distance of nearly 10 miles, and from this same point the Yates Knob ridge extends northwestward in a less regular form toward the Unaka range. These mountains lie between Toe River on the north and the Swannanoa on the south. At the southern end of the Blacks they touch the Blue Ridge. They are from 15 to 30 miles south of Roan Mountain and 30 miles southwest of the Grandfather. The group has an area of more than 170,000 acres, about 20,000 acres of which are cleared. Forests cover nearly the entire area of the Craggy Mountains, though they are not so dense, nor so nearly in their original condition as are those on the Black Mountains, as more or less lumbering has been done along both the eastern and the western slopes. Some of these slopes, too, have suffered much from fire and are almost destitute of young trees and undergrowth. The densest and most primitive forests of the region lie on the west slope of the Black Mountains about the headwaters of Caney River. (See Pl. XIII.) Those on the east slope of the Blacks are much lighter and have suffered more from fires. FORESTS OF THE CENTRAL INTERIOR MOUNTAIN RIDGES. | ||||

|

Topography. |

The Balsam Mountains make up the longest of the cross ridges in the Southern Appalachians, extending from Mount Guyot, the highest of the Unakas, on the Tennessee line, in a general southeasterly course to Mount Toxaway (Hogback) on the Blue Ridge, near the South Carolina line, a distance of 40 miles. They reach their highest point in Richland Balsam—6,540 feet. Northeast of and less prominent than the Balsams are the Newfound Mountains. which form another and shorter cross ridge, extending from Mount Pisgah northward to the Unakas. South of the Balsams, the Cowee and Nantahala mountains each form short cross ridges, rising to less than 5,500 feet, which extend from the Blue Ridge on the Georgia State line northwesterly to the Great Smokies of the Unaka Range. | ||||

|

Agriculture. General forest conditions. |

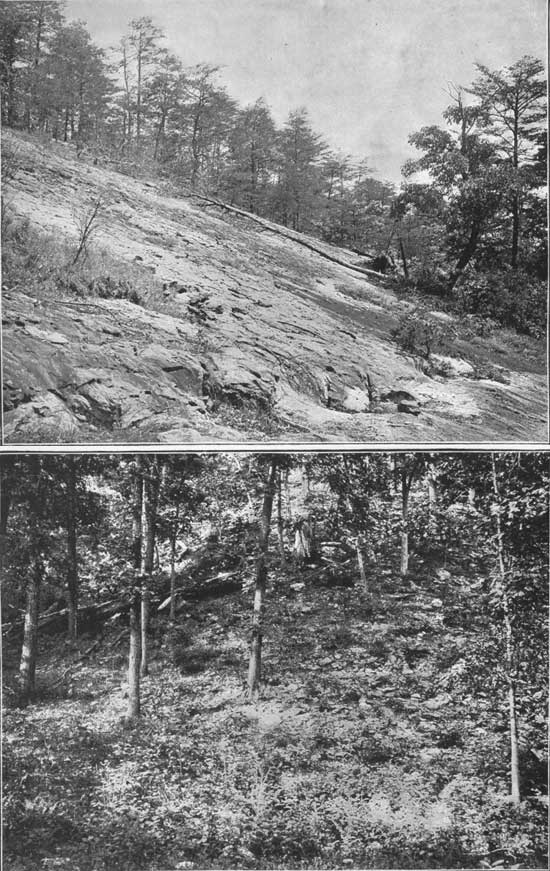

These cross ridges are in their general features all much alike, with frequent steep rocky slopes and sharp crests. There is very little land on them suited to agriculture, except in the narrow valleys and coves. (See Pl. XLIII.) The soils are generally thin and light, in some places sandy, rarely clayey. These mountains, however, are surrounded by agricultural valleys, except near the northwest ends of the Balsam and Newfound mountains, where these join the Unakas. The forests on the northwestern portion of the Balsam Mountains are really a continuation of those of the Great Smokies, and resemble them in the species represented and in the general forest conditions. The forests on the east side of the Balsams and on the Newfound, Cowee, and Nantahala mountains are munch alike, but the Balsam Mountains are much more heavily wooded than the others, especially on their northern slopes, and have more of the softer woods, like linn, buckeye, and ash. The southern slopes of all are lightly wooded and have been injured by fire to some extent, so that in places the forest is open and young timber trees are scant. Much of the best timber has been culled from the Newfound and Nantahala mountains. The larger part of the forest land on the eastern spur of the Balsams (about Mount Pisgah) is under forest protection. | ||||

| |||||

|

Forests about the Newfound Mountains. |

The forests of the Newfound Mountains are formed of hard woods, largely oak and chestnut, associated with white pine. As they lie nearer the main line of the Southern Railway, and on account of the topography were easily lumbered, they have been more culled than those of the other cross chains. Some general lumbering has been done on Wolf and Shut-in creeks, and an attempt has been made to remove all the merchantable timber from some large tracts. At most, however, it amounts to only severe culling. The forests of the Cowee and Nantahala mountains are very much alike. They consist of hard woods, in which oak, chestnut, hickory, and maple form the largest element. There is almost an entire absence of coniferous growth, the hemlock, which is associated with the hard woods elsewhere, being almost wanting here. Much culling has been done in the forests at the north ends of these mountains, where they are nearer the Murphy branch of the Southern Railway. | ||||

|

Forests about the Balsam Mountains. |

The Balsam Mountains are more heavily timbered than the other cross ridges. On both northern and southern slopes there are deep, cool hollows, or coves, with fertile soil, producing vigorous growth, and as there has been very little culling these forests are very nearly primeval. They consist of typical Southern Appalachian hard woods, associated with hemlock and spruce. On the northern slopes the softer of the hard woods form the dominant element, as linn, ash, buckeye, and yellow poplar, while the proportion of oak and chestnut is smaller. The hemlock is associated with these in the deep hollows, while spruce crowns the summits of the northern slopes. On the southern slope oak and chestnut form the larger proportion of the timber, and there are less of the lighter woods and of hemlock and almost no spruce. The eastern, or French Broad River slope about Mount Pisgah, is lightly timbered with oak and chestnut and has been much damaged by fire. At present, however, it is under forest protection, and a vigorous young growth is springing up. Railroads are now being built into the forests on both the north and south slopes in order to exploit the timber. The almost precipitous walls of the beautiful Nantahala Gorge, nearly 2,000 feet deep, are forest covered throughout their entire extent. (See Pl. XLII.) FORESTS OF THE GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS. | ||||

|

Topography and forest conditions. |

This segment of the Unakas is the largest mountain mass in the Southern Appalachians, and it contains the largest area of continuous forest (see Pl. XVII), with the smallest number of clearings. It includes the Smoky Mountains from the Big Pigeon River on the northeast to McDaniel Bald on the southwest, and that part of the Balsam Mountains which lies west of Soco Gap, with their numerous spurs and subsidiary ridges. The region is rough and rugged on both north and south slopes, and rises from a low valley level of about 1,500 feet at the larger streams to more than 6,000 feet along the crests of the highest mountains. The wooded area begins on the western foothills of the Smoky Mountains in Tennessee, covers the northwestern and southeastern slopes of the Great Smokies (see Pl. XLIII) and the slopes of the Cataloochee Mountain. The broad agricultural valleys of East Tennessee lie against these mountains on the northwest, but elsewhere they are surrounded by a rough country of lower mountains, with narrow, intervening agricultural valleys. Less than 10 per cent of this area is cleared. The clearings are few and small, and lie chiefly some miles distant from the crest of the ridge. | ||||

| |||||

|

Nature and extent of the forests. |

The forests are chiefly of hard woods, with a large amount of coniferous growth around the higher summits and in the deep, cool hollows. On the drier slopes, and especially on the south sides, oak and chestnut form the greater part of the timber, with some black and yellow pine on the ridges. The timber in the hollows is more varied and the stand is heavier, poplar, birch, linn, and buckeye being associated with the oak and chestnut. The finest and largest bodies of spruce in the Southern Appalachians occur here, along the crest of the ridge and the north slope of both the Cataloochee and Smoky mountains. There are about 20,000 acres of spruce and nearly as much hemlock. There is no spruce on the Smoky Mountains southwest of Silers Meadow. The forests of the north slope of the Smoky Mountains have been much culled and injured by burning and pasturage. There is yet a great deal of fine timber, however. Fires have also done much injury on the south slope, especially to hard woods, and the growth is often very open on account of the suppression of young trees by burning for a great number of years. The valleys of Cataloochee and Big Creeks are heavily timbered, though they have been culled to some extent, and the ridges have often been burned. A railroad is now being built up Big Pigeon River in order to exploit the timber on these streams. A railroad is also under construction up Oconalufty River to remove a part of the timber from the east prong of that stream. FORESTS OF THE SOUTHERN END OF THE APPALACHIANS. | ||||

|

Topography. |

South of the Nantahala cross ridge the Appalachian Mountains no longer consist of two well-defined parallel ranges with prominent cross ridges, but break up into a number of small, low mountains, or small ridges, with broad, alluvial valleys or low hills between them, or in some places there are a series of low ridges which are separated by deep, narrow, gorge-like valleys. In northwestern Georgia their identity is entirely lost, and they pass into the hills of the Piedmont Plateau. While only a few of these mountains have an altitude of more than 4,500 feet, the topography is rough, as the stream level is much lower than it is further northeastward, not being more than 1,000 feet. The resisting character of the rock—quartzite, sandstones, and slates—which forms these mountains, which have eroded into sharp-pointed ridges with deep, narrow intervening valleys, has added to the ruggedness of the region and its picturesqueness. Some of the largest of these mountains are the Blue, Flat Top, Shooting Creek, and Valley River mountains. | ||||

|

Forest conditions. |

The northern slopes and hollows are often well wooded with hard woods, chiefly with oaks, chestnut, maples, and hickories. The southern slopes are lightly wooded with oaks, hickories, and black and yellow pines, which also form the forests on the spurs and foothills. In very many places the forest is open and thin, and many trees are defective. The undergrowth is often dense, consisting of numerous sprouts from young trees which have been killed by fires, and many shrubs which grow in the partial shade of the thin forest cover. In other places there is almost no underwood and no young growth. Repeated fires have injured much of the timber on the southern slopes and greatly impaired the general forest condition. These fires are far more frequent and severe than in the hard-wood forests northward, on account of the dryer climate and soil and the large amount of inflammable pine, and the resultant injury to the timber is more evident. On account of the thin, dry soil the trees are smaller and less vigorous than farther north, and the constant destruction of the humus by the fires still further lessens their growth and keeps them small. The soils of the mountains are generally thin and sandy and not at all productive agriculturally. In many places they are very rocky, so that tillage would be impossible. The altitude is too low for grass. About three-fourths of the area is at present in forest. Some of it is second growth, but only a small part of it is such. There are occasional clearings, however, around the base of the mountains and in the hollows. Lumbering has been in progress in many places and some of the choicest timber has been removed, especially along and near the Marietta and North Georgia Railroad.

The three agencies that have wrought changes in the forests of the Southern Appalachians are the fires, the lumbermen, and the clearer of lands for farming purposes. | ||||

|

Injury by forest fires. |

Fire has come as an oft-repeated scourge since the days of early Indian occupation. | ||||

|

Extent and nature of their damages. |

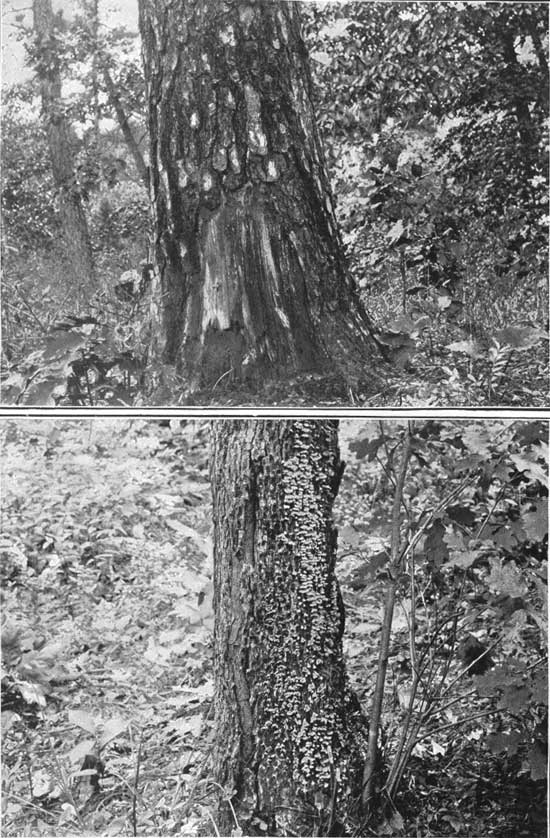

More than 78,000 acres of the region examined have recently been so severely burned as to kill the greater portion of the timber, but the greater aggregate damage has been done by lighter fires creeping through the woods year after year, scorching the butts and roots of timber trees, destroying seedlings and forage plants, consuming forest litter and humus, and reducing that thatch of leaves which breaks the fall of raindrops. Evidence of such fires is found over approximately 4,500,000 acres, or 80 per cent of the entire area. (See Pl. XLVI.) | ||||

| |||||

|

Reproduction prevented. |

The effect of forest fires is seldom appreciated, especially in this region, where so few timber trees are killed. The killing of mature timber trees is, in fact, from the nation's point of view, the least damage of all; for were only the mature trees killed a dozen saplings would stand ready to fill the place of each, but the fires affect the saplings much more than the large, thick-barked trees, and, too, where spring fires are habitual seedlings can not grow, as they are killed when very small. A forest under such conditions can not reproduce itself. The timber trees die out and are replaced by brush that sprouts from the roots. One who studies these effects can see everywhere the damage by fire in dead trees, scorched butts, hollow trees, dead saplings and seedlings, in clumps of sprouts from roots of fire-killed trees, in the openings, the half-forested land, and in the annual weeds that occupy the burned areas, nature using their humble efforts to cover the nakedness of the misused land. | ||||

|

Fires increase violence of floods. Fires impoverish the soil. |

The damage by fire causing a loss of the earth cover does not end with erosion, for it also prevents water from penetrating and being stored in the earth. The roots of trees penetrate deeply into the subsoil, and as they decay leave a network of underground water pipes. The mulch of forest leaves encourages numerous ground-boring worms and beetles that keep the soil of an unburned forest porous, not only favoring the absorption of water, but also retarding the capillary rise of moisture to the surface and its loss by evaporation. The mosses and humus of a well-conditioned forest form wet blankets, often a foot thick, the function of which is so evident that it need not be explained here. The dissipation of the chemical elements of plant food into the atmosphere by fire and the rapid leaching away of the slight residue contained in the ashes is another injurious effect of the forest fires. | ||||

|

Fires in this region best prevented by Government supervision. |

The experience of the older countries should serve us sufficiently to prevent our making a similar mistake of policy concerning our mountain lands. That the same effects follow the careless policy of burning mountain land in this country as in Europe is proved by the already desolate condition of large areas in the Rocky Mountains and the plainly legible signs of the coming consequences in the Appalachian region. | ||||

|

The effect of lumbering. |

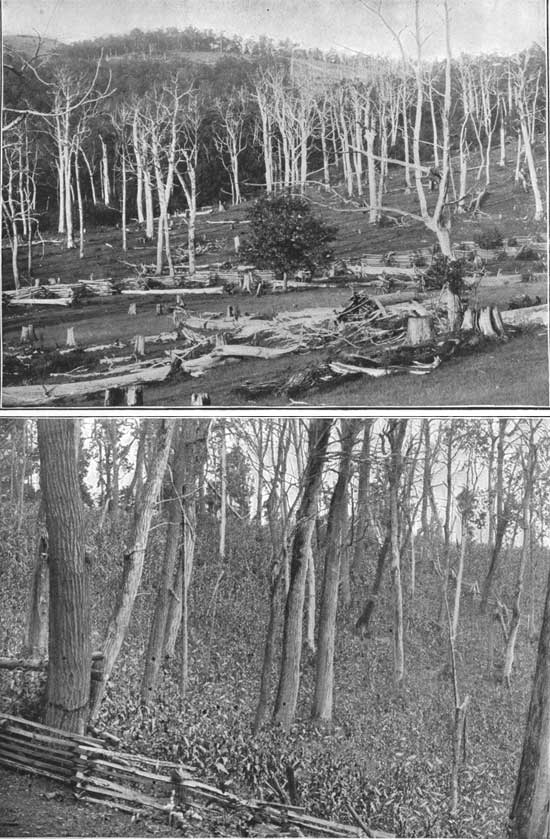

The lumberman has been increasing his activities at a somewhat rapid rate, and he is yearly going farther into the forests. The damages he causes come not so much from the trees he cuts in culling the forest as from the additional trees and seedlings of valuable species which he destroys in his lumbering operations, and the greater destruction from forest fires which follow him, fed by the tops and other brush he leaves scattered through the forest. By his irregular cutting, reducing forest conditions, he renders impracticable the inauguration of economic, conservative forest management. | ||||

|

The effect of clearing steep mountain sides. Percentage of land already cleared. |

Following in the wake of the fire and the lumbering, and surpassing them both in the completeness and permanency of the damage done, is the man who clears for ordinary agricultural purposes mountain lands which should forever remain in forest. The clearing of lands in this region for agricultural purposes has progressed slowly but steadily during the past century as the population increased, until at the present time there are 1,200,000 acres (24 per cent) cleared out of a total of 5,400,000 acres examined. (See Pl. XII.) When it is considered that the settlement of this region has been in progress for more than a century the extent of the area devoted to agriculture is small. The reason for this is found in the unprofitableness of cultivating lands with such steep slopes. The cleared lands are mostly limited to the alluvial bottoms along the streams, the rounded valley hills, the lower mountain spurs, and the lower slopes of the larger mountains themselves below 4,000 feet elevation. In some localities, especially in the region around Roan Mountain and on the Blue Ridge north of Gillespie Gap, there are large areas of cleared land at an elevation of from 3,500 to 5,000 feet; but these are mostly grass farms, are not subject to continuous tillage, as are the corn lands below, and hence do not deteriorate so rapidly. Some of the slopes that are cultivated are very steep—from 30 to 40 degrees—some of them too steep even for the mountain steer and bull-tongue plow, and must be cultivated entirely by hand. | ||||

|

Method of clearing. The process of erosion. |

The staple grain produced throughout this region is corn, which yields more heavily than small grain and is more easily managed on the steep slopes. On clearing the land for cultivation the standing trees are girdled to kill them, so that neither their shade nor their growing roots will injure the crops. Some of the trees thus killed are used for fencing and fuel, but the greater number of them fall in a few years and are then rolled into heaps and burned. Corn or buckwheat is usually grown on these newly cleared fields, between the girdled trees during the first season (see Pl. XLIX.) Following this corn may be planted one or two years more; then small grain, either wheat, rye, or oats, for one or two years; then grass for a few years; then follow worthless weeds, and then the gullies. When first cleared most of this mountain-side land is covered with a layer of humus several inches thick, and the soil below is black and porous, owing to the large percentage of vegetable matter it contains; but on cultivation and exposure to the sun and washing rains this organic matter is rapidly dissipated. In this process most of the soil is washed away; the remainder shrinks and consolidates, thus losing much of its power to absorb water rapidly, and loses its fertility by the continued eroding and dissolving action of the rains. | ||||

| |||||

|

Early abandonment and ruin of these cleared mountain slopes. |

Hence these cleared mountain lands have a short-lived usefulness, and new clearings are made to replace the fields which from year to year are abandoned because they cease to be productive. A few years of cultivation for fields on these steeper mountain slopes usually brings them to the end of their usefulness for agricultural purposes. This may be followed by a few years of pasturage, and then come abandonment and ruin. (See Pls. I, XX, and XXI.) Over the eroded foothills, along the eastern base of the Blue Ridge and western base of the Unakas, young pines may slowly cover again the eroded surface of the mountain slope, but over the more elevated portion of the Appalachian Mountain region the erosion, whether it be in gullies, visible for miles, or in the more common form in which the whole surface moves downward, is so rapid that the hard-wood forests, slower to reproduce, do not readily regain their footing, and hence the work of land destruction continues. | ||||

|

Fields now abandoned should be reforested. |

The limited alluvial or bottom lands in this region being the most productive and easiest cultivated, were naturally the first to be cleared, and these are now nearly all in cultivation; but with an increasing population the demand for additional fields to cultivate has led to the clearing of these mountain-side patches successively higher up the slopes, until now the area of these clearings considerably exceeds the area of the bottom lands. This process has gone on the more rapidly because of the rapidity with which these steep lands have been worn out and abandoned. There are yet many places where the gentler slopes might perhaps be cleared to meet the agricultural demands of the region, but unquestionably the steeper areas already cleared should be at once reforested in order to prevent their early ruin. All lands in this region remaining cleared for farming purposes should be kept in the highest state of cultivation, and those of even the gentler slopes should be carefully terraced, and as far as possible kept in grass or orchards. The effect of exposing mountain lands to the full power of rain, running water, and frost is not generally appreciated. The greater part of our population lives on level land and does not see how the hills erode, and even in the hills nearly all the people go indoors when it rains and therefore do not half understand what is going on. In the dashing, cutting rains of these mountains the earth of freshly burned or freshly plowed land melts away like sugar. The streams from such lands are often more than half earth and the amount of best soil thus eroded every year is enormous. | ||||

|

A remedy suggested. |

The individual owners are to a great extent helpless in preventing these unwise cuttings, clearings, and forest fires. Some of them can care for their own lands, but they can not, owing to their small holdings and small incomes, regulate the policy which controls adjacent areas. Only cooperation on a great scale, such as Government ownership could provide, can stop these forest fires, check this reckless clearing, and preserve these resources to the best advantage. The two great needs of this mountain region are: 1. The use of the land for the purpose to which it is best adapted, which would require the keeping of 80 to 90 per cent of it in forest, while the cleared land should be kept in the highest state of cultivation for farm products. 2. Efficient and cheap transportation for the forest products. | ||||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sen_doc_84/appa1.htm

Last Updated: 07-Apr-2008