|

Senate Document 84 Message from the President of the United States Transmitting A Report of the Secretary of Agriculture in Relation to the Forests, Rivers, and Mountains of the Southern Appalachian Region |

|

APPENDIX A. (continued)

By OVERTON W. PRICE.

|

The protection of the headwaters of important streams in order to prevent floods and perpetuate water powers, the preservation of a great natural health resort and of important agricultural resources, are perhaps the most valuable results that would follow the creation and management of the proposed Appalachian Forest Reserve. The application of practical forestry in this region by the Federal Government would bear fruit also in the maintenance of a sustained supply of hard-wood timber, in the production of a steady and increasing income therefrom, and in providing a forcible object lesson to show the advantages of careful and conservative forest management. | |||||||||

|

Percent methods of lumbering and their results. |

Lumbering is one of the principal industries of the Southern Appalachians. The agricultural resources of the region must remain limited because of its ruggedness and the low percentage of arable land. Its development as a grazing country is hampered by the lack of winter forage and the temporary life of the grass covering in the lower slopes. Its main resource of the future will be its hard-wood forests, upon whose maintenance depends very largely the best and most permanent development of western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee. The existing supply of merchantable timber has already been seriously reduced, while repeated fires and unregulated grazing have in many localities greatly impaired the quality and health of the forest, as well as the chance of its successful reproduction. Although there is still enough wood left to fill the local demand, the cost of logging it is constantly growing with the increasing distance between the market and the source of supply. Around each settlement there is a rapidly widening area which has been stripped of all merchantable timber under methods which too often render it practically valueless for the production of a second crop. In many localities serious harm has already been done, which only time and care can remove. A continuance of such methods will within the near future destroy this great natural resource of the Southern Appalachians—the lumbering of its valuable hard woods to supply a steady and growing demand.

The application of practical forestry to the proposed reserve would not only preserve the productive capacity of the forest within its boundaries, but it would also provide a proof of the results of conservative forest management which would be of value in inducing private owners of forest land in this region to adopt the same measures. There is no surer or quicker way of convincing the lumberman of the Southern Appalachians that conservative lumbering pays better than ordinary lumbering than by an experiment on the ground, based upon a thorough study and effectively carried out. | ||||||||

|

Government management would yield a profit. |

The question of direct returns from the proposed reserve is, from the point of view of the Federal Government, a secondary one. Its highest benefit will lie in those indirect returns which are of so vital an importance to the best development of this region and its resources. However, that the forests of the Southern Appalachians can under systematic and conservative measures be made to yield a profit from their management is certain. Although local stumpage values are not sufficiently good to warrant the application of an elaborate system of forest management, they are high enough to make conservative lumbering a sound business measure. The pecuniary advantage of practical forestry depends naturally upon whether it offers better returns than those to be had from ordinary lumbering. Since it reduces present profits slightly in order to insure a second crop of timber upon the lumbered area, its superiority from a business point of view rests upon the safety and value of the second crop. Serious danger from fires, a poor market, excessive difficulties to overcome in logging, or any other adverse condition which seriously impairs stumpage values, may render the probable future returns from a forest insufficient to justify conservative measures in lumbering it. | ||||||||

|

Conditions in this region favorable for conservative forestry. |

Not only is there no unfavorable condition in the Southern Appalachians which is sufficient to render practical forestry inadvisable as a business measure, but the opportunity offered for good returns from careful and conservative forest management is a peculiarly favorable one. The forest contains valuable timber trees, which not only command a high price at present, but are rapidly increasing in value for the lack of satisfactory substitutes, notably in the case of Black Walnut, Cherry, Hickory, Yellow Poplar, and White Oak. The transport of timber presents some difficulties, as in all mountain countries. These are, however, seldom sufficient to impair seriously the profits from lumbering. Effective protection from fire is practicable without prohibitive expense, while in its rate of growth, readiness of reproduction, and responsiveness to good treatment the forest offers silvicultural opportunities which are seldom excelled in this country.

Practical forestry in the Southern Appalachians must comprise those modifications of the present methods of lumbering which will not only insure a fair profit upon present operations, but will preserve the productive capacity of the forest and provide for the desired reproduction of the timber trees. Unnecessary damage to the forest and total lack of provision for a future crop is characteristic of the lumbering now carried on in this region. Logging operations have generally shown an inexcusable slovenliness, as foreign to good lumbering as to practical forestry. | ||||||||

|

Wasteful methods followed. |

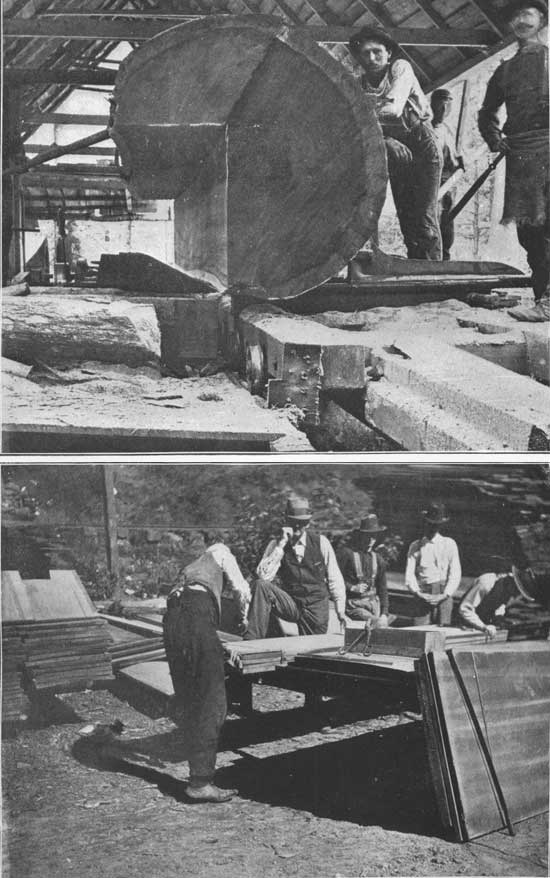

A clean lumber job is seldom seen. There is great waste of good timber through poor judgment in gauging the log lengths and in cutting stumps much higher than is necessary. Butting off unsound portions of trees is not always done; trees not wholly perfect are sometimes left to rot where they fall. Care is seldom taken to throw trees where they will do the least harm to themselves and to others, and in consequence lodged and smashed trees are very common. Overlooked sound trees are also numerous. However, criticism of lumbering in the Southern Appalachians must take into consideration the circumstances which led to it. Almost all of the work has been done by the farmers of the region in order to supply their fuel and other household material and to add to the poor living afforded them by their farms. These men are often hampered by lack of capital, are generally wanting in the knowledge requisite to good lumbering, and have had always to contend with the difficulty of obtaining expert loggers to carry out the work. Nevertheless, the nearness of large bodies of merchantable timber, among which are valuable kinds, such as Cherry, Black Walnut, Hickory, and Yellow Poplar, has usually made a fair profit possible under even the most thriftless logging methods. This desultory cutting has been going on for years, and although the individual efforts have been small, they have removed the merchantable timber from the larger portion of the accessible forests.

When the waning supplies of timber in the North and East some fifteen years ago forced the loggers of those regions to the South, the application of skillful and systematic methods of lumbering began in the Southern Appalachians. The newcomers, through the investment of commensurate capital in logging outfits, the thorough repair and extension of logging roads, and the generally businesslike mode of attack characteristic of the trained lumberman, have reaped a profit from their operations entirely impossible under the slipshod, desultory lumbering methods of the settler. | ||||||||

|

Nature of the damages. |

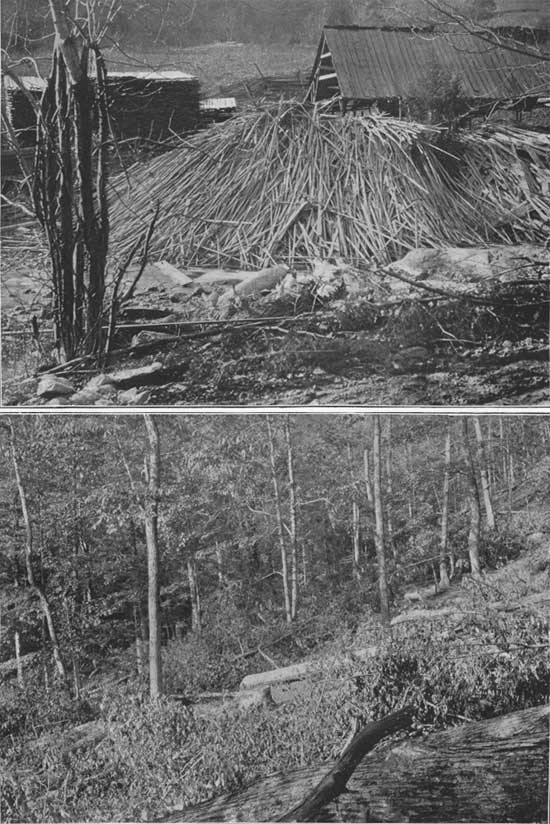

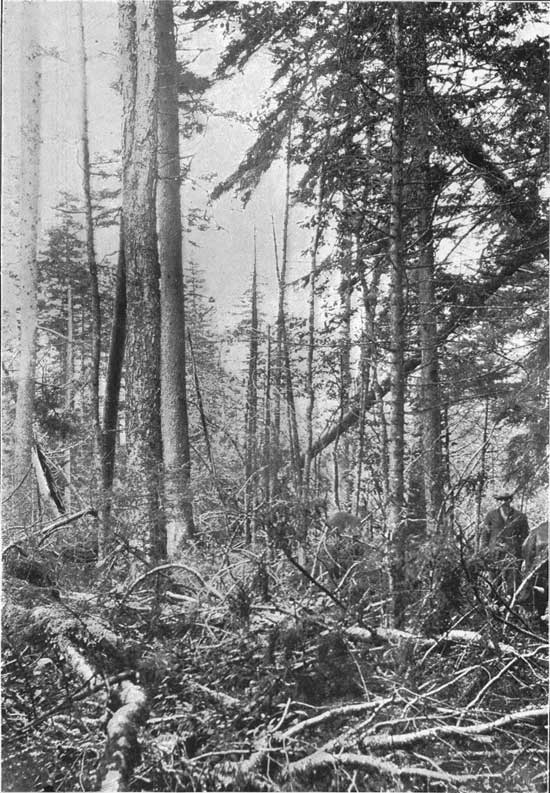

The harm done to the forest in both cases is very great in proportion to the quantity of lumber cut. This is due largely to the size of the trees and the fact that little care is taken in the fellings. The damage to young growth is increased by the absence of snow and by the fact that trees are often cut when they are in full leaf. The breaking down and wounding of seedlings and young trees by the snaking of logs to the roadside or the river is in some degree unavoidable; but the damage is often much in excess of what is necessary. (See Pl. LIII.) There are often, however, many more snakeways, or skidways, than are necessary, and the application of a little system in laying them out would save time and young growth on a lumber job. On the higher and steeper slopes it is often the habit—and one which can not be criticized too strongly, except in those rare cases where it is absolutely necessary on account of the gradient—to roll the logs from top to bottom, merely starting them with the canthook. A 16-foot log, 3 feet or more in diameter, can gain momentum enough in this way to smash even fair-sized trees in its path, and when it passes through dense young growth it leaves a track like that of a miniature tornado. The practice is in line with others to be observed in the Southern Appalachians, such as the common habit, for example, of leaving to rot the "deadened" trees which stand over clearings. There are cases in which these clearings have been inclosed with fences built of rails split from prime black walnut, with no other excuse than that the walnut happened to he within easier reach than either oak or pine. Under such methods, in which there is not only an absolute lack of provision for a future crop but often a marked absence of that forethought, skill, and aversion to waste which go to make clean lumbering, most of the logged over areas in the southern Appalachians are only saved from entire destruction of the standing trees by the generally scattered distribution of the merchantable timber. | ||||||||

| |||||||||

|

In the application of conservative forest management to that portion of the forests of the Southern Appalachians included within the proposed reserve, the first aim should be to protect them from fire. The safety of the forest from fire must form the foundation of any system of practical forestry which is to be permanently successful. Fire has done and continues to do enormous damage in this region. The chief cause lies not in malice or in carelessness of campers or of lumbermen, but in the ancient local practice of burning over the forest in the autumn, under the belief that better pasturage is thus obtained the following year. | |||||||||

|

Protection against forest fires. |

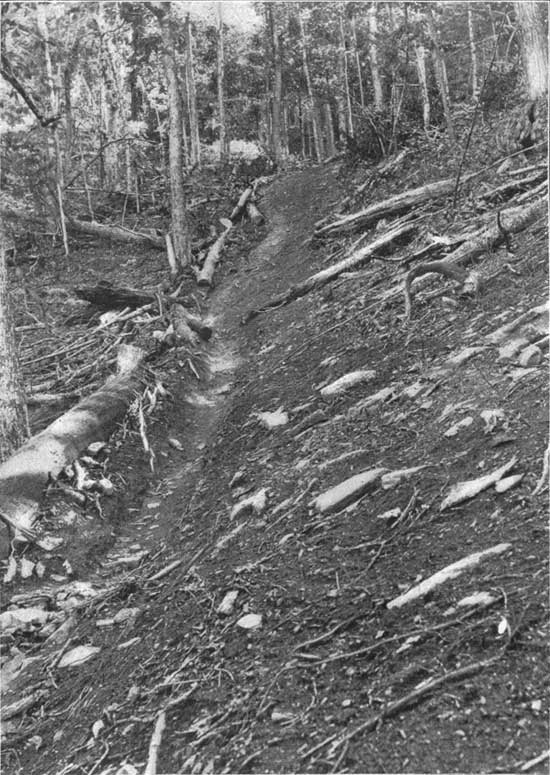

The fires are started by the settlers upon the area which is to serve as a sheep or cattle range the following season, and are permitted to burn unchecked. The result is that, except where confined by roads, streams, or clearings, they often spread from the wood lots of the foothills, in which they are set, to the forests of the higher mountains, there to burn unmolested until rain, snow, or lack of inflammable material puts them out. The hard-wood forests of the Southern Appalachians are by no means so inflammable as the coniferous forests of the North and West. Forest fires in this region are seldom more than ground fires, and only under the influence of exceedingly high winds in a dry season become uncontrollable. With an active and adequate force of rangers and a thorough system of trails, the protection of the proposed reserve would be practicable. The good results of its preservation from fire would be twofold. In addition to the evident benefits of efficient fire protection upon the forest would be the forcible example provided to prove that the forest untouched by fire yields in the long run better and more plentiful pasturage than if it be annually burned over. The modification of present methods of grazing in the Southern Appalachians, like the modification of present lumbering methods, will follow proof of its advantages much more rapidly than it would follow propaganda. The one is no less important to the best development of this region than the other. The advantages of both could in no way be better established than by their practical illustration in the proposed reserve. The mountain forests of the Southern Appalachians are silviculturally the most complex in the United States. They contain many kinds of trees, varying widely in habit and also in merchantable value, and the forest type is constantly changing with the differences in elevation, gradient, and soil. Their best management is difficult, because the lack of uniformity in the forest renders it necessary constantly to vary the severity of the cutting and to discriminate in the kinds of trees which are cut, instead of following only those general rules which suffice where there are fewer species represented and the forest conforms more closely to a single type.

| ||||||||

|

Improvement in method of lumbering. |

In order to reproduce these forests successfully and to minimize the damage done by lumbering, first of all it will be necessary to have a radical improvement in the fellings. Such an improvement is entirely practicable without additional cost per 1,000 feet B. M. of timber felled. It often requires no more labor to fell a tree up a slope than down it, or upon an open space rather than into a clump of young growth; and it is in just such cases as these that unreasoning disregard for the future of the forest is commonly manifested in the Southern Appalachians. | ||||||||

|

Culling the forest under old system. |

In the selection of trees to be felled the small farmers, who for a long time were the only lumbermen in the Southern Appalachians, have been governed by the same considerations that govern lumbermen elsewhere. They have taken the best trees and left uncut those of doubtful value rather than run the risk of loss in felling them. Furthermore, the fact that they have lumbered generally on a very small scale and have often had great difficulties with which to contend in the transport of logs has led them to extremes in this respect. The result is that they have reduced the general quality of the forests in a measure entirely disproportionate to the amount of timber cut. As a rule, only prime trees have been taken, and those showing even slight unsoundness have been left uncut, except where the stand of first-class timber was insufficient. Diseased and deteriorating trees remain to offset the growth of the forest by their decay and to reduce its productive capacity still further by suppressing the younger trees beneath them, while in the blanks made by the lumbering worthless species often contend with the young growth of the valuable kinds. In other words, the lumbering has closely followed the selection system, but the principles governing the selection have usually been at variance with the needs of the forest.

In order to bring about successful reproduction of the desirable species and to maintain the quality and density of the stand, lumbering in the mountain forests of the Southern Appalachians must be governed by the following main considerations: | ||||||||

|

Removal of faulty trees. |

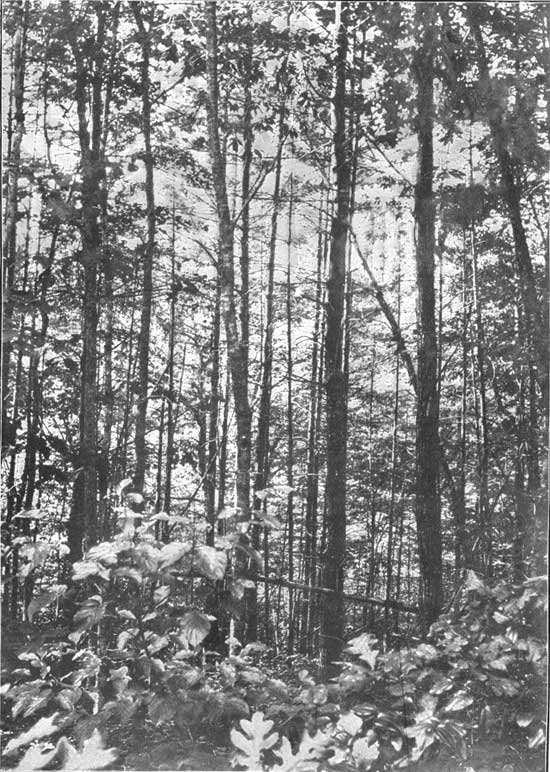

(1) Remove all diseased, overripe, or otherwise faulty trees of a merchantable size where there is already sufficient young growth upon the ground to protect the soil and serve as a basis for a second crop of timber. (See Pl. LIV.) In extreme cases, where the condition of the forest is seriously impaired by the presence of a large number of such trees or where they overshadow and seriously retard promising young growth, their removal may be financially advisable when the sale of product no more than pays the cost of the logging. | ||||||||

| |||||||||

|

Cut so as to encourage growth of valuable species. |

(2) So direct the cuttings that the reproduction of the timber trees may be encouraged in opposition to those of less valuable kinds. This can not be successfully accomplished in the Southern Appalachians by cutting a diameter limit merely. A limit will by all means be advisable for each species, based upon a study of its rate of growth and the proportion which different diameters bear to its contents in board feet. It will be frequently necessary, however, to leave trees of a merchantable diameter where their removal would seriously impair the density or where seed trees are necessary. | ||||||||

|

Careful selection of seed trees. |

In the leaving of seed trees many considerations are involved, only a few of which can be mentioned here. The Walnuts, Oaks, Hickories, and Chestnut should be favored, since their seed is too heavy to be carried by the wind, and much of it is eaten by animals. The marked tendency of the pines (see Pl. LV), Hemlock, and Yellow Poplar to reproduce by groups must be encouraged. On south slopes and in dry localities generally, where Dogwood, Sourwood, and Scrub Oak contend with the timber trees, great care must be taken not to disturb the balance between them. The rich, moist soil of the Poplar coves is particularly likely to produce a luxuriant growth of weeds and brambles instead of tree seedlings if too much light is admitted to the soil, while the Ash, Cherry, and Basswood, which are only sparsely represented in the mature stand and are further handicapped among the young growth by their strong demands upon the light, will require an exceedingly conservative method of management. | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sen_doc_84/appa2.htm

Last Updated: 07-Apr-2008