|

Senate Document 84 Message from the President of the United States Transmitting A Report of the Secretary of Agriculture in Relation to the Forests, Rivers, and Mountains of the Southern Appalachian Region |

|

APPENDIX A. (continued)

By H. B. AYRES and W. W. ASHE.

|

In order to present in more convenient form detailed information about the forest conditions in the Southern Appalachians, the following descriptions have been arranged by drainage basins, beginning at the northeast and moving around the mountains to the place of beginning, in the order given below. This arrangement will serve an important purpose in the consideration of water flow and also the question of transportation. The region has for this purpose been divided into the following fourteen drainage areas: New River, South Fork of Holston River, Watauga River, Nolichucky River, French Broad River, Big Pigeon River, Northwestern Slope of Smoky Mountains, Little Tennessee River, Hiwassee River, Tallulah and Chattooga rivers, Toxaway River, Saluda River and First and Second Broad rivers, Catawba River, Yadkin River.

| |||

|

Topography. |

New River, a feeder of the Ohio through the Kanawha, drains the eastern portion of the Appalachian Plateau lying between the Blue Ridge on the southeast and Iron Mountain on the northwest. The sources of the tributaries are high, from 3,000 to 5,000 feet, but the river valley below the junction of the North and South forks has been eroded down to an altitude of 2,500 to 2,000 feet. The resulting topography is a system of deep, narrow valleys and ravines, among which are a few isolated peaks (having an altitude of 5,000 feet and upward) and occasional flats, which are of two classes—(1) in high altitudes remnants of the old plateau, and (2) along the larger streams, narrow, sedimentary flats. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

The greater portion of this area has been cleared, although mostly too steep to be arable. The hills are cleared for grazing, to which industry this land is better adapted than to agriculture, in view of the great erosion and the difficulty of maintaining roads in this remote and hilly region. Excellent crops of hay and grass are the rule on new land, and the custom is to crop and graze a clearing until it wears out, then clear a new field. | ||

|

Erosion. |

Many of the old hill fields are now worn out by close pasturing and by the erosion of unprotected humus, and are being gullied to the underlying rock by every shower. | ||

|

The forest. |

The forests of large area are limited to the higher altitudes on the isolated peaks between the North and South forks, and on Balsam and Iron mountains which form the northwestern rim of the plateau. On the southeastern slope of Balsam Mountain is an almost unbroken forest, approximately 5 miles square; but the long, narrow strip of woodland on Iron Mountain is considerably broken by clearings and burns, while the portions of Pond Mountain and White Top draining into New River have on them only remnants of the old forest. Scattered among the clearings of the valley are wood lots, left usually on ridges and north slopes. Composition.—The trees of these forests are principally oaks and chestnut, with a mixture of white pine, hemlock, black spruce, black gum, cherry, poplar, ash, cucumber, buckeye, linn, maple, birch, and many unimportant species. Altogether there are about 80 species of trees. Condition.—All the forest is inferior in condition, being either culled, fire scarred, or full of old and defective trees, while a dense undergrowth usually covers the steep slopes. The condition of these neglected forests would improve readily under forestry, as valuable species are abundant and reproduce easily and grow rapidly wherever they have an opportunity. The outlying isolated wood lots, surrounded by cleared land and held by thoughtful farmers, are noticeably in better condition than the larger wild areas in the remote mountains.

| ||

|

Topography. |

This area comprises the northern slope of the mountains between Watauga and New rivers, and is principally a long, narrow strip of steep mountain side, having a northward exposure and an altitude of 2,500 to nearly 6,000 feet. In addition to this uniform tract, this drainage system comprises the semicircular interrupted basin drained by Beaver, Tennessee Laurel, Green Cove, and White Top Laurel creeks, which join and cut through the mountains near Damascus. | ||

|

Soil. |

In this area are two distinct classes of land—mountain slopes and alluvial or sedimentary basins. The mountain slopes, steep and principally underlaid by quartzite, have light soil, with thorough drainage both on surface and underground, while the sedimentary valleys—as Holston River bottoms, Shady Valley, Laurel Bloomery, and others—have deep, loamy soils, remarkably fertile. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

On the Tennessee Laurel substantially all the arable land is under cultivation, but along Shady Valley and White Top Laurel only a small portion of the arable land is cleared. The Holston River bottom is cleared to the foothills of the mountain. This land is well adapted to diversified farming, but is now devoted principally to corn and grazing. | ||

|

Erosion. |

Erosion is less marked in this area than in most others, a fact which is probably due to the larger proportion of wooded area. The Tennessee Laurel is, however, subject to sudden rises, endangering the narrow bottom lands and even the lives of travelers who must cross the numerous fords in the gorge. There is also much erosion of soil locally on the older neglected fields of the tributaries of the Tennessee Laurel and on the poor portions of the foothills of Holston Mountain. | ||

|

The forest. |

Excepting a few mountain pastures, all the mountain ridges are wooded, and both east and west of Damascus are large areas of unbroken forest, covering both mountain and valley. The north slope of Holston Mountain also remains entirely wooded. The forest of this drainage varies, naturally, with the soil, altitude, and exposure, and has also been seriously modified by fires. The northward slopes of Holston and Iron mountains are lightly timbered with oaks, black pine, chestnut, gum, etc., with some hemlock and white pine in ravines, nearly all culled. The southward slopes of the same mountains, and especially the lower portions of these slopes, are better wooded, except as cleared or deadened for grazing, and have some heavy stands of hemlock and white pine, among which hard woods are freely distributed. The steep slopes west of Damascus and east of Como Gap are in a very inferior forest condition, owing largely to the long-continued prevalence of fires, which have not only prevented a vigorous growth, but have even driven out the most valuable species. The trees of the ridges and north slopes are short and crooked, and as a rule the land is very imperfectly stocked. and also very brushy. The forests of some of the tributary basins are in excellent condition, having more moisture and better soil and having been less injured by fire. Except on the driest portions, lands cut or burned over are quickly restocked with valuable species, while the dry ridges and summits are soon occupied by chestnut and oak sprouts or by black pine, gum, sourwood, or trees of similar value. Prevention of fire and judicious thinning would soon develop a valuable forest on these northern slopes, where now there is very little material that is marketable.

| ||

|

Topography. |

This basin, tributary to the Holston, lies almost entirely within the Appalachian mountain region. The main source of the river is on Grandfather Mountain, a prominent peak of the Blue Ridge, while the last mountain gorge is passed near Elizabethton, Tenn., where the river leaves the mountains. The highest points of this basin are Holston Mountain, 4,300 feet; Snake Mountain, 5,594 feet; Rich Mountain, 5,369 feet; Grandfather Mountain, 5,964 feet; Beech Mountain, 5,222 feet; Yellow Mountain, 5,600 feet; Roan Mountain, 6,313 feet, and Ripshin Mountain, 4,800 feet. These are on the borders. The interior portion is broken into many subordinate ridges, reaching an altitude of 3,000 to 4,000 feet, with deep, narrow valleys eroded down to an altitude of 3,000 to 2,000 feet. | ||

|

Soil. |

Derived directly from granite, gneiss, and schist, by decomposition, the soil of the mountains and ridges has been fertile, much of it very fertile loam of excellent physical as well as chemical composition. Washing, however, has carried much of the desirable material down to the valleys and left the soil of the ridges inferior, especially on southward slopes. The valley soil is of two general classes, (1) the red clayey loam of the lower foothills and (2) alluvial bottom land, some of which is too porous or too stony, but mostly excellent farm land. Altogether, the newly cleared soil is very good, but many burned ridges and old washed fields are in a very poor condition, notably in the valley of Little Doe. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

Along Stony, Cove, and Roane creeks, Doe River, the main Watauga, and many minor valleys are excellent large farms, growing corn, wheat, rye, oats, grass, and vegetables. On almost every creek and in many of the mountain coves are families depending upon the farm for the greater portion or all of their living. While much has been cleared that would be better adapted to timber growing if a timber market were within reach, there is altogether a large area that is best adapted to farming. It is safe to say that a broad economic policy would have little or no more forest land cleared than is now under cultivation, and that attention should be given to keeping what land is cleared in good condition rather than to clearing more to be exhausted and washed until worthless. | ||

|

Erosion. |

In this basin it is estimated that the average damage by erosion during the season of 1901 to farm land has been not less than $1 per acre. This amounts to over $200,000 for the whole basin. Damages to railroads amounted to $250,000, 19 bridges and about 25 miles of track being washed out. The damage to wagon roads can hardly be estimated. In many places entirely new roads were necessary. The damage was probably $500,000 altogether. Buildings and personal property destroyed swell the total loss to something like $2,000,000. | ||

|

The forest. |

Distribution.—The remaining forests are on the ridges and mountain ranges and spurs. These are somewhat dotted with clearings, especially in the granitic region south of the Iron Mountain Gorge and along the north slope of Beech Mountain and the Elk Creek Basin. The lowlands have been almost entirely cleared. Composition.—The hard woods, in which the oaks and chestnut predominate, form a mixed forest on most of the area; some ravines carry hemlock almost exclusively, and on some of the ridges white pine is one of the principal timber trees. Spruce is found almost exclusively in some high mountain groups, while beech rules in zones on high mountains and on the crests of some ridges. Condition.—Nearly all of the forest has been or is being culled of its most valuable timber, and is rapidly becoming inferior by the predominance of old and defective trees and undesirable species. Fires are preventing a good growth on large portions, although they are seldom so severe as to kill much timber. The few areas that are in good forest condition are merely enough to illustrate what forestry might do. Reproduction.—Vigorous sprouts, seedlings, and saplings abound on old cuttings and burns, and prevention of fire and some judicious thinning would soon develop a forest that would justify transportation companies in building railroads to haul its products to market.

| ||

|

Topography. |

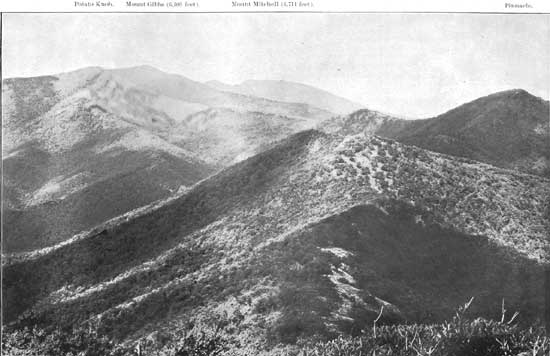

A large portion of this basin lies within the mountain region. Its three principal tributaries, North Toe, South Toe and Caney rivers, as well as several creeks of large size, are entirely between the rims. Mount Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Rocky Mountains, and Roan Mountain, well known by "Cloudland," the highest hotel of the East, are both on the borders of this basin. In the central part is a large portion of hilly agricultural land, and along creeks are many narrow strips of flat, alluvial bottom. In cutting through the northwestern rim of the plateau, however, the streams have worn long, deep gorges through the Unicoi and parallel mountain ranges, and the narrow tributary valleys of this portion of the basin have rapid torrential streams, very little bottom land, or none, and very steep and rocky mountain slopes. | ||

| |||

|

Soil. |

The soil is in general very good, especially that of the lower portion of the interior basin, which was evidently deposited as a sediment before the gorge was cut to its present depth. The mountain coves also contain deep, dark loam, which is very fertile. Some of the ridges, however, have a light, shallow soil, owing to erosion of humus and loose earth. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

Twenty-four per cent of this basin is cleared land, most of which is grazed, although much of it is well adapted to diversified farming, which is unprofitable now because of distance from market. | ||

|

Erosion. |

A great drawback to agriculture is found in the cutting away of uncovered hill fields by the dashing rains and the deposition of the eroded material on other fields in the bottoms. The floods of the Nolichucky are well known. They may be partly due to the topographic configuration of the area, by reason of which a rise of the three main tributaries at one time may cause a flood in the river. There is no room for doubt, however, that the large amount of cleared land in this basin greatly increases the floods. Every resident who has known the river ten years or more states very positively that the volume of water is now much less constant than in former years. In Yancey County many of the steep slopes in the basins of Caney River, Bald Creek, and in the vicinity of Burnsville, which have for many successive years been planted in corn or small grain, are deeply eroded, and some such fields have been abandoned. The same statement will apply to much steep land in Mitchell County, on the waters of Cane and Big Rock creeks, and in the vicinity of Red Hill. The lands at higher elevations, which have been retained in grass, are less damaged. The alluvial lands of the Nolichucky were severely washed by several freshets during the spring and summer of 1901, the most severe being that of May 20 to May 23, which caused damage to land and other property in Mitchell County to the amount of $500,000 or more. All of the soil on the flood plain of Cane Creek, 9 miles in length, was removed, leaving only the large stones and rocks, and many fine farms on North Toe River were destroyed. More than twenty dwellings, several mills and dams, and many million feet of saw logs are known to have been washed away. In addition, the damage to the public highways was $50 or more per mile, aggregating $50,000, while the railroad sustained an equal loss in the injury to roadbed, bridges, and culverts. (See Pl. XXXV (b) showing wreckage from Mitchell County, lodged near Erwin, Tenn.) | ||

|

The forest. |

Although greatly broken by clearings, large areas of woodland remain on the Unicoi and parallel ranges on the northwestern border, on Roan Mountain, the Blue Ridge, the Black Mountain group, and the western tributaries of Caney River. In composition there is great variety. Spruce and balsam prevail on the highest portions of the Black, Roan, and Sampson mountain groups. Hemlock, birch, maple, cucumber, ash, buckeye, linn, and other moisture-loving trees line the ravines, while oak, chestnut, gum, and other hard woods cover the ridges of the higher altitudes. Oak and pine form a less dense cover, usually very brushy, on the ridges of lower altitude. In forest conditions there is also great variety, dependent largely upon the prevalence of fire. Fires are freely set during autumn, winter, and spring, and great injury to timber, forest seedlings, and soil results. A large proportion of the timber trees are defective, and much of the woodland area is imperfectly stocked. The reproduction of trees is remarkably vigorous on cuttings, burns, and old fields, and growth is rapid. The prevention of fire and the application of improvement cuttings would wonderfully increase the value of the forest, which is the great natural resource of the mountainous portion of this basin:

| ||

|

Topography. |

This long and wide crescent-shaped valley heads on the Blue Ridge, which it drains from Swannanoa Gap to Panther Tail Mountain (62 miles) and reaches entirely across the highlands, which it leaves near the Tennessee line, about 80 miles from its source. Around the borders of this basin are the Craggy Mountains, Swannanoa Mountains and Estatoe, Panther Tail, Pizgah, and Max Patch peaks, all high, forest-covered mountains. In Madison County, where the river has cut through the northwestern rim of the region, is a large area of broken, mountainous ridges, with very steep and rocky slopes. A great portion of the interior basin, however, is smooth enough and fertile enough for grazing or farming. | ||

|

Soil. |

The soil is extremely variable, though in general very good. That of the lower hills is a red clay, a fine sedimentary deposit. It is fertile and recuperates readily, but erodes rapidly when uncovered. The ridge land, as usual, is well adapted to grass, but if closely pastured erodes rapidly and soon becomes worthless. The best soil is found in the coves and on the broad alluvial bottoms which border the river and its larger tributaries from the Blue Ridge in the southeast to the head of the gorge near Marshall. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

Substantially all the lowland is occupied by farmers, and many of the plantations are very productive and well adapted to mixed farming. This is, in fact, one of the best agricultural valleys to be found in the East. The principal difficulties to be met are erosion of surface soil on the hills and destructive floods on the bottoms. Much of the mountain region is also under cultivation. The cove lands are mostly cleared, and cleared mountain-side pastures dot the landscape, as viewed from every high point. | ||

|

Erosion. |

This basin is no exception to the rule for the region. Tobacco-growing on the lighter soils of the hills exhausted field after field, and finally the whole industry was abandoned, leaving large areas of desolate land exposed to the cutting action of raindrops and to gullying by running water. The same process has been in operation on old farm land and pastures. until on many small tracts, as on the southward slopes of Poverty Hollow, near Barnardsville, there is but little soil left. There is hardly a farm in the entire basin that is not more or less gullied, although much care is taken by a few of the more thoughtful farmers to keep the earth covered by a vigorous crop. The inundations of the bottom lands are also seriously damaging, and the general testimony is that they increase as more land is cleared. There is evident need of every protection against erosion in this valley, where so many people and so much valuable property are concerned, and where sudden heavy downpours of rain are common. | ||

|

The forest. |

Distribution.—The higher mountains are still forested, and the ridges and slopes above 3,000 feet are mostly covered, although some of the ridges, as Elk, Spring Creek, and New Found ridges have on them large proportions of cleared land, and the mountain sides are often dotted with clearings. Composition.—In this region we have a mixed forest, in which the oaks and chestnuts predominate, with a sprinkling of white pine, hemlock, linn, gum, beech, birch, maple, ash, hickory, Shortleaf pine, poplar, cherry, walnut, and many other species of less importance. Condition.—Besides the usual inferior condition of the natural forest, fires, grazing, and culling have greatly reduced its original quality. Bordering the farms are many fine stands of sapling second growth, but the remote mountains are full of defective trees and brush. Reproduction.—Sprouts and seedlings spring up readily. White pine, shortleaf pine, poplar, ash, walnut, and cherry all abound in the forests in the form of promising young trees. Sumac and locust here reproduce rapidly and are well adapted to cover and prevent erosion on the old fields. The farmers need to be taught that to recuperate their lands, instead of letting them stand bare and idle "to rest," they should grow clover and cowpeas on them, and always keep them covered as much as possible.

| ||

|

Topography. |

Big Pigeon River rises among the Balsam and Pizgah mountains, cuts its way through the Unaka Mountains, and joins the French Broad on the Tennessee Plain. It drains an interior agricultural basin which is oval in outline, the longer axis northwest, parallel to the general course of the stream, and almost entirely within the Appalachian Mountain region. It is circumscribed by lofty mountains, with many peaks more than 6,000 feet in altitude. Many minor ranges, springing from the surrounding mountains, converge toward the middle of the basin, dividing it into deep, narrow valleys, except near its upper end between the towns of Canton and Waynesville, where there is a broad, open valley of alluvial plains and rolling hills, dotted with low mountains. | ||

|

Soil. |

The soils are loams and sandy loams, mostly fine grained in texture, derived from gneiss and schists, though in the mountains they are more siliceous and coarser—there the product of decomposed sandstones, quartzite, and conglomerates. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

This basin is eminently adapted to grass, except where very sandy, and grass is the chief product of the region. Corn ranks next in importance; while the cultivation of wheat is largely confined to the broad valley of the Pigeon, between Canton and Ferguson, and to the Richland and Fines Creek valleys. Apples are extensively raised and have a wide reputation for their quality, and truck farming is yearly assuming greater importance. | ||

|

Erosion. |

The alluvial valley lands have been little injured by freshets, and the soils of the uplands, with few exceptions, have not suffered severely from erosion, though a few badly gullied slopes, due to the continuous cultivation of corn, are to be seen in the older settlements. | ||

|

The forest. |

The scarlet, black, and white oaks, associated with black pine, formed at one time an extensive forest on the hills between Canton and Waynesville, but this land, where not under cultivation, is now in second-growth forest. The forests of the mountains are of typical mixed Appalachian hard woods, with, in the Balsam and Pizgah ridges, a small amount of black spruce at high elevations, and some white pine in the lower part of the basin. These forests have been culled only of the most valuable timbers. All species reproduce excellently under the proper light conditions; and with exclusion of fire and a judicious system of lumbering there would be no difficulty in perpetuating this forest and increasing the proportion of valuable species in its composition.

| ||

|

Topography. |

This tract is a mountain side between altitudes of 1,500 and 6,700 feet, and is drained by Little Pigeon and Little rivers into Holston River, and by Abrams Creek into Little Tennessee River. The surface is eroded into fan shaped basins, very steep, and often precipitous near the summit, with high, narrow ridges dividing the main drainage basins. There is no alluvial land of consequence except at Briar Cove, Gatlinburg, Tuckaleechee Cove and Cades Cove. | ||

|

Soil. |

In general the soil is light-colored and shallow, especially on the ridges and steep slopes. In the coves, however, and along the foot of the ridges where the slope is more gentle, humus has accumulated and the soil is fertile. In general physical quality the soil is loam or clay loam. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

Corn is the principal farm crop, and 50 bushels per acre are sometimes grown on the best lowlands. This land can not compete with the alluvial river bottoms, however. Most of it is farmed only because it is cheap land and affords a chance for a poor man to make a living (by hard work.) The higher altitudes are favorable to fruit, grass, and vegetables, and also to stock raising in a limited degree, as cattle may roam in the woods and subsist on seedlings, shrubs, and weeds, and hogs in occasional years find abundant mast. | ||

|

Erosion. |

In general, the earth is fairly well covered, and thus protected from erosion, but the few old pastures are worn and gullied here, as elsewhere on hilly land. In this region streams heading in unbroken forest are notably clear and their banks show little fluctuation in volume of water, while those from cleared lands are muddy and inconstant. While present erosion is limited, there is evidence that it would be very great if large areas of the earth were uncovered. | ||

|

The forest. |

Distribution.—With the exception of a few "balds" or grassy areas on the higher summits, and the alluvial lands of the lower coves and creek valleys, the forest of this great mountain side is practically unbroken. Composition.—The species of trees growing here number over 100, an unusually large number, for one locality. Northern and southern trees are close neighbors, and all may be studied in traversing the different zones of altitude from 1,500 to 6,700 feet, instead of the necessary 1,000 miles of latitude at an altitude of 1,000 feet. Almost every tree enumerated in the accompanying list (p. 93) grows here. Condition.—While some remarkably fine timber trees are here, the general average is far inferior to what might be grown with so favorable a soil and climate. Fire, grazing, and culling have reduced this forest considerably below its natural condition. Imperfect trees and inferior species are abundant, while some of the burns and cattle ranges are very deficient in stand. Reproduction.—Hardly any other forest in the country would respond so readily to the forester's care and demonstrate so plainly that nearly all of this tract is best adapted to timber growing.

| ||

|

Topography. |

Little Tennessee River with its tributaries drains a large area, extending from the Blue Ridge on the south to the Great Smoky Mountains on the north, including all of the territory between the basins of Big Pigeon and Hiwassee rivers. Its larger tributaries are the Tuckasegee from the east, the Oconalufty from the northeast, the Cheoah from the southwest, and the Nantahala from the south, while the upper portion of the Tennessee drains the extreme southern portion, heading on top of the Blue Ridge. These waters pass through the Tennessee into the Ohio River. The upper or southern part of the basin lying on the northwest slope of the Blue Ridge is an elevated plateau region, having an altitude of more than 3,000 feet, with low, rounded granite knobs and few high summits, and broad alluvial flats, the deposit of the slow streams. The Balsam, Great Smoky, and Unaka mountains, with many crests more than 6,000 feet high, form the watershed on the north and west, and from these descend into the northern portion of the basin many swift streams, which have carved deep narrow valleys, leaving high intervening ridges with steep and rugged slopes. The watersheds between several of these streams are high and rough mountains, especially in the Cheoah, Nantahala, and Cowee ranges. The lower part of the basin includes some of the most rugged land in the southern Appalachians, with only a very small part suited for tillage, and few alluvial bottoms; but in the upper part much of the mountain land is not steep, and there are several large and fertile valleys. | ||

|

Soil. |

The soils in the upper part of the basin are sandy, derived from granite, or in the Little Tennessee River, around and above Franklin, where most of the good farms are located, from schists, and are deep and fertile red loams. In the narrow valleys around the high mountains, where sandstones, quartzite, and conglomerates prevail, the soils are generally thin and sandy, and poor agriculturally, but on north slopes and in hollows are well suited to forests. The alluvial bottom lands along many of the streams are also light and sandy, though those of the Little Tennessee are silts of the finest texture. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

All of the land available for tillage has been cleared. Corn is the staple crop on both alluvium and upland, the yield of small grain, grass, and apples being much smaller than in other mountain counties farther north. At high altitudes and on some of the stiffer soils grass thrives, but on the whole the soils are too light and too subject to drought for either grazing or forage grasses. Orchards have been planted, but are much neglected, and only a few apples are produced for market. | ||

|

Erosion. |

Much of the best valley land has been badly washed, especially on Tuckasegee River and Scott Creek. There are also many badly worn steep slopes on these streams and elsewhere. | ||

|

The forest. |

In general, the mountain ranges and spurs, and also the ridge lands of the valleys, are still principally wooded, although many clearings are found in mountain coves and on mountain slopes. The principal clearings, however, are on and about the alluvial lands, which appear on the map like broken chains along the larger tributaries. The largest unbroken forest areas lie on Oconalufty, Cheoah, and Tuckasegee rivers, in the northern, northwestern, and northeastern parts of the basin, though there are some areas of fine forest at the head of Nantahala and Little Tennessee rivers, in the southern part of the basin. At lower elevations the forests are of oaks and hickories, associated with black pine. On the thin soil of the slopes along the Blue Ridge small scarlet and white oaks, with occasional bodies of hemlock, form the forest, while elsewhere in the mountains typical Appalachian hardwoods prevail, with some few thousand acres of black spruce capping the highest summits of the Smoky and Balsam mountains. The best timber has been much culled for 20 miles from the Southern Railway, which crosses the middle of the basin. Repeated forest fires, started with a view to improve the pasturage, have destroyed much timber on dry south slopes, and by continued suppression of the young growth have greatly reduced the density. Reproduction, however, is good, and if the open woods were protected there would soon be a fine young growth beneath the old trees. Proper distribution of species could easily be secured by judicious cutting while logging.

| ||

|

Topography. |

This drainage is tributary to the Tennessee River, which the Hiwassee joins above Chattanooga, and comprises the eastern tributaries of Hiwassee River above Murphy, equivalent to the western slope of the mountainous divide between Little Tennessee and Hiwassee rivers, which divide is a cross range between the Blue Ridge and the Smoky Mountains. The altitude of this tract ranges between 1,500 and 5,000 feet. Spurs from 5 to 20 miles long reach from the divide toward the river, while deep valleys extend from the river far into the mountains. The mountain sides are steep and often rocky, while the creek valleys, of which there are six prominent ones, have considerable areas of alluvial flats and rolling foothills. | ||

|

Soil. |

Even the alluvial flats along the rivers and creeks have a large proportion of clay, and the foothills are almost entirely clay. The mountain sides are loamy, the coves very fertile, and the soils of the ridges light, often stony. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

Corn is the principal grain crop. Grass does well on low alluvial lands and in mountain coves, but burns out on the foothills. There are some fine farms on Valley River, Peach Tree, Tusquitee, Shooting, Tiger, and Hightower creeks, but large areas of hill land are worn out and abandoned to broom grass. | ||

|

Erosion. |

This basin, or part of it, seems unusually liable to floods, as is shown by the cutting of banks and the washing of fields. About the head of Peach Tree Creek, in 1900, several "waterspouts" are said to have occurred at one time, and the water from these joining formed a torrent that swept across fields and roads, doing great damage. Evidences of similar floods and of great erosion on old fields are to be found in almost every mile of travel. The uselessness of clearing the ridge lands has been discovered by the farmers, and no advances of cleared land have recently been made toward the mountains, but many old fields lie wasted and wearing away, scantily patched with broom grass, persimmon, and sassafras. | ||

|

The forest. |

Distribution.—The mountains and spurs are principally forest-covered, although here and there clearings have been made in coves and along the tributary creeks. The larger creek valleys and the river valley are principally cleared. Composition.—In this region is found a suggestion of the difference between the forest of the cool highlands and that of the southern slope of the Blue Ridge. In passing from the highlands we are leaving the region of most vigorous tree growth and approaching the piny regions. Oaks and hickories are more numerous, but shorter and smaller; hemlock and white pine are less abundant; the birches and hard maples become rare, and the southern red maple, pitch pine, and shortleaf pine more abundant. Condition.—In condition, too, there is a noticeable contrast. Fires have been more prevalent and have kept decaying vegetation pretty thoroughly consumed. Fires have killed less timber, but have done no less damage by preventing that new growth which perpetuates the natural forest. On isolated wood lots and near clearings are many tracts of thrifty saplings, but the general forest condition, owing to fire and grazing, is inferior to that of the plateau. Reproduction.—The first and essential step toward the improvement of this forest would be the prevention of fire. Much of the stand is now so thin that thinnings need not be made at once. Sprouts and seedlings will start freely, and the forest would grow well as soon as the forest soil reached natural condition again. But few cattle are ranged in the mountains now, as the grazing has been too much reduced by repeated fires.

| ||

|

Topography. |

This tract covers the entire basin of these rivers above their junction and drains into the Atlantic through Savannah River. Lying on the southeastern slope of the Blue Ridge, the altitude varies from 5,500 feet on Standing Indian, 5,100 feet on Ridgepole, 4,769 on Scaly Mountain, and 4,931 feet on White Sides to 1,000 feet at the junction of the Tallulah and Chattooga rivers. Many of the peaks and spurs are extremely bold, and there are numerous deep gorges and canyons. Along the creeks, especially along the Upper Tallulah and its tributaries, are alluvial bottoms of considerable area. Nearly all of the cleared land (11 per cent of entire tract) of this system is on creek bottoms. | ||

|

Soil. |

Derived from gneiss and granite, the soil is generally of good physical composition, except in the foothills, where a stiff red clay predominates, which erodes readily and is hard to cultivate. The bottom lands are loamy and fairly fertile, but the ridges have been so much burned and washed that on them the soil is light colored, thin, and poor. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

Corn is the principle crop. Grass, except in the higher altitudes, does not hold. Sweet potatoes, cane, and cotton are grown along the southern limit of this tract. Peaches do well in the lower altitudes, and apples are grown on the mountains. | ||

|

Erosion. |

The impervious clays of the foothills are frequently found barren and gullied, because left uncovered. The mountain ridges, having many stones and pebbles in their soil, resist erosion much better than the clays, but this advantage is counteracted by the steepness of their slopes, and the bed of every rivulet is eroded to the underlying rock. The creek bottoms are hardly less liable to damage. Sudden downpours of rain (11 inches have been known to fall in forty-eight hours) often cause such rises in the creeks as to cover the fields with gravel or cut them away. | ||

|

The forest. |

Distribution.—All this tract is forest land except the creek bottoms and a few mountain coves, which have been cleared and together amount to 11 per cent of the area. The denser portions are in the coves at the higher altitudes. Composition.—There is a noticeable contrast between the forests of the interior mountain region and of those of this region about the headwaters of the Tallulah and Chattooga rivers. Here the oaks are in greater predominance, and the hickories and Southern pines are more abundant, while beech, birch, maple, buckeye, and other lovers of cool air and abundant moisture are notably less. White pine and hemlock hold to the higher altitude, but are noticeably rare along the foothills. Condition.—In condition, also, the forest is inferior to that of the highlands. The injuries by fire are greater. The rate of growth is further retarded by drought, and probably by occasional spring frosts killing buds and young leaves. The greater portion is in the condition of natural forest, with many old, crooked, fire-scarred, and otherwise defective trees and inferior species, and with subordinate saplings, crooked and retarded. Because of prevalent fires the stand is imperfect, many spaces being covered with mere brush where a stand of good timber is possible. Along the line of the old railroad grade from Walhalla to Rabun Gap much burning was done at the time of grading, and now the portion then severely burned is covered with a dense stand of saplings, principally oaks and hickory. Reproduction.—The absence of protection from fire on its dry slopes would be the main difficulty in bringing this forest into good condition, as sprouts and seedlings spring up quickly where fire can be prevented. The effect of the no-fence law is plainly noticeable south of the Chattooga River, where the forest is more severely injured by fires, which are there fiercer because of more combustible material.

| ||

|

Topography. |

This basin drains into the Atlantic through Savannah River. The headwaters rise far back in and in fact have, by erosion, almost worked their way through the Blue Ridge. The principal peaks about the headwaters are: Sheep Cliff, 4,653 feet; Double Knob, 4,417 feet; Great Hogback, 4,700 feet, and Cold Mountain, 4,500 feet. The descent from these peaks is rapid and amounts to 3,500 feet in 6 miles on the Toxaway. There are few prominent points within the basin, but the canyons are deeply eroded, and cascades are almost continuous along the Whitewater, Horsepasture, and other tributaries. | ||

|

Soil. |

Derived from gneiss, and in general well forested, the soil is fertile. It is usually a loam of good physical quality. The ridge land is, of course, less fertile, yet is capable of growing valuable timber. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

The few clearings that have been made yield good crops of grass and corn, but the roughness and steepness of the surface will prevent any extensive farming in this portion of this drainage. So little of the land has been cleared that eroded fields are not a prominent feature of the landscape, as in many other localities, but enough has been cleared to show what the effect would be. | ||

|

Erosion. |

The soil, having numerous pebbles in it, does not erode by rainfall as readily as clay or sand, but, on the other hand, the slopes are so steep and the torrents so fierce that it would be unwise to uncover any but the gentlest slopes and the most fertile soil. | ||

|

The forest. |

The forest of this tract is but slightly broken, only 5 per cent being cleared. The northern portion, lying well up on the Blue Ridge, has substantially the same species as the forest of the highlands. The oaks, hemlock, and white pine predominate. Chestnut, ash, hickory and gum are also abundant. Lower on the slopes the oaks, hickories, and black and yellow pines become more prominent. The forests of this region are variable. They have been seriously injured by fires, and as a result have some large openings on the ridges. Rhododendron and kalmia constitute a dense undergrowth in the hollows. Defective trees are abundant throughout, but the stand of valuable species is poor. Improvement in forest condition may be rather more difficult here than elsewhere, owing to abundance of brush and the liability to fire. White and shortleaf pine are the most promising species for a future forest.

AND FIRST AND SECOND BROAD RIVER BASIN. The small portions of these two drainage systems examined are so similar they may be described together. Both lie on the southeastern slope of the Blue Ridge, and both drain into the Atlantic through Santee River. | ||

|

Topography. |

The Blue Ridge at the heads of these basins is low—about 3,000 feet—and the lowest land covered by these descriptions is about 1,200 feet. The slopes drained by the Saluda are steep and often precipitous, and include Table Rock and Caesars Head, both bold rocky points, affording two of the grandest views in the whole region. The cascades and falls through the glens of South Saluda and other creeks are very pretty. There is very little alluvial land on the creeks until they reach the plain at the foot of the Blue Ridge. The slopes drained by the Broad rivers are more moderate. The spurs here reach out long distances toward the plains, while between these spurs are rapid but seldom cascading creeks, with somewhat interrupted alluvial bottom lands. | ||

|

Soil. |

In both regions the soils are derived from granite, gneiss, and schists, which, when they remain in place, make excellent land, but when washed and the finer sediments left in one place, the coarser in another, become less desirable, as the clays thus formed are too stiff, too impervious to water, and too hard to work, while the gravels are too porous and too light. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

Corn and cane are the principal crops of this region. Some grass is grown on the small clearings in the higher altitudes, and some inferior orchards are seen. Sweet potatoes are grown on every plantation, and a few small cotton fields were found on the edge of the plain. | ||

|

Erosion. |

The lack of grass on most of this area leaves the sun face exposed to the cutting action of falling rain, and the eroding effect is so severe and so evident that, in the foot hills, no one attempts agriculture upon the ridges. Even the gentler slopes on the border of the alluvial bottoms are often gullied until they have become not only worthless themselves, but are a source of damage to the bottom lands below, which receive the material washed from them. (See Pl. LXVII.) The slight protection furnished by the frequently burned forests does not prevent the washing away of the humus from the woods, and being so light, it is carried far down the stream to still waters before it finds a lodging place. | ||

|

The forest. |

Substantially all the ridges and steeper slopes are forested more or less densely, while the creek bottoms are cleared. The cleared area on the Saluda comprises 6 per cent of that basin, while 20 per cent of the area of the Broad basins is cleared. In composition these forests are principally oaks and hickory, with a sprinkling of nearly all other species mentioned in the accompanying list (p. 93). In condition these forests are very inferior. There is very little log timber. Many of the trees are fire-scarred; many, though old, are small because fire and erosion of humus have retarded growth. Much of the area has a deficient stand, because fires have killed seedlings. To improve this forest it would be necessary to prevent fire and possibly to thin out defective trees and undesirable species. The species to be favored here are poplar, ash, walnut, shortleaf pine, post oak, and white oak, and, in the higher altitudes, white pine.

| ||

|

Topography. |

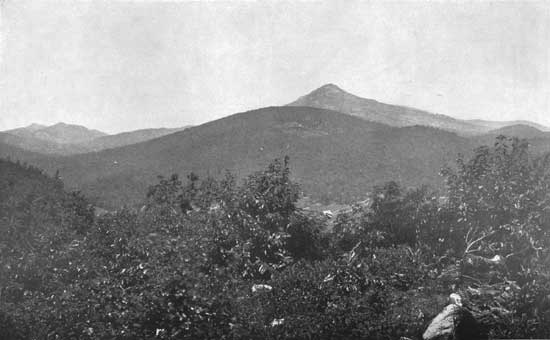

This area, as here limited, includes the eastern or southern slope of the Blue Ridge, with its numerous spurs, from Blowing Rock southward to Edmondson Mountain, and is drained by the headwaters of the Catawba River, including Johns and Linville rivers, and the north and south forks of the Catawba, directly through the Catawba River into the Atlantic. The elevated crest of the Blue Ridge, with few points on it at a lower elevation than 4,000 feet, and rising at Grandfather Mountain and Pinnacle to an elevation of more than 5,000 feet, forms the western and northern limits of the area; and from it extend steep, rugged spurs with a general north and south trend, gradually diminishing in altitude as they recede from the parent range, dividing the region into numerous parallel, narrow, often gorge-like, valleys. This type of valley reaches its culmination in the gorge of the Linville River, the wildest and most picturesque stream of the southern Appalachians, in its descent of 2,400 feet in 20 miles, from the Linville Falls to the foothills. The alluvial lands in the valleys, except those along the Catawba for a few miles above Marion are limited to narrow strips bordering the streams, or, as on the lower Linville and many tributaries of the Johns River, are altogether lacking. | ||

| |||

|

Soil. |

The soils of the uplands, derived from the decay in place of quartzite, slates, sandstone, and gneiss, are sandy, or sandy loams, and are thin and poor, with few exceptions. Along the larger streams the alluvia are silty and fertile; along the smaller they are sandy and often less productive. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

In the lower valleys corn and small grain are the common crops on the alluvia; corn the exclusive crop of the steeper slopes. Corn, oats, grass, and apples form the staple crops in the elevated valleys and on slopes at high altitudes. | ||

|

Erosion. |

The alluvial lands of the Johns River and the Catawbas have been severely damaged by recent freshets, which have in many places washed away the soil to a depth of several feet, leaving only the rock and gravel, while in other places the agricultural value has been destroyed by the deposition of beds of pure sand or coarse gravel above the alluvium. Soils on steep slopes which have been under tillage, especially those in corn, have also been badly damaged. The forests, except those of a few limited valleys at high elevation, are confined to the slopes, nearly all of the alluvial bottoms having been cleared. | ||

|

The forest. |

Composition.—They are formed of hard woods, chiefly oaks, associated with pines, white or black; or of mixed hard woods—oaks, chestnut, maple, birch, linn, ash, and poplar—associated with hemlock in the deep hollows and on south northern slopes. Condition.—Nearly all south and east slopes, especially at a low elevation, have been damaged by fires to some extent. The best hard woods have been culled from much of the area, and the best white pine from the lower part of the valley of the Johns River and from a portion of the Upper Linville. There is yet much hard wood, largely oak, on the headwaters of the Catawbas, Johns, and Upper Linville rivers. Reproduction.—Reproduction of hard woods is free by stool shoots and seed, and of pine by seed. Protection from fire is greatly needed. This, with improvement cuttings, would soon develop a valuable forest.

| ||

|

Topography. |

The portion of the basin of this river examined includes the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge, with its outlyers from Bullhead Mountain southward to Blowing Rock, and is drained by the head streams of the Yadkin and all of its northern tributaries eastward to and including Roaring River. The crest of the Blue Ridge, with an average elevation of more than 3,500 feet, limits the area on the north; and from this numerous sharp and steep spurs penetrate the area, dividing it into a series of narrow parallel northwest-and-southeast trending basins, from the southern ends of which the streams emerge and unite to form the Yadkin, at an elevation of about 1,000 feet. The topography is rough, the slopes of the ridges steep, and the intervening valleys narrow, showing unchecked natural erosion from a high plateau region to a lower base level, in a country with rock of varying hardness and an abundant rainfall. | ||

|

Soil. |

The alluvial lands in the valleys are narrow strips or small bodies, seldom more than a few acres in extent, of dark, sandy-loam soils, rich in humus, and fertile, or occasionally of coarse sand and poor. The soils of the uplands, produced by the decomposition of slates, sandstones, and gneiss, are highly silicious and often coarse and poor. On north slopes and in the hollows accumulated mold adds to the fertility and checks the removal of the finer clayey particles, while the poverty of the naturally infertile south slopes is augmented by repeated fires which destroy the litter and facilitate the removal of the finer particles of the soil by the heavy rains. | ||

|

Agriculture. |

Corn is the staple crop, both on the alluvial lands and on the slopes at lower elevations; while corn, grass, and some apples are cultivated on the shady north slopes at high elevations and in the deep, cool hollows that indent the face of the mountain. Some of the alluvial bottoms have been damaged by being washed and gullied by freshets, or by the deposit of coarse sand and gravel brought down from the mountains. | ||

|

Erosion. |

Many of the steep slopes, exposed to erosion by the naked cultivation required for corn, have been gullied to the bed rock, and their agricultural value is temporarily destroyed. Many such abandoned fields are being colonized by windsown pine seedlings, which check further erosion and rebuild the soil. | ||

|

The forest. |

The forests, which are confined to the slopes, are formed of hard woods, chiefly oaks, associated with pine (black, rarely with white) on the drier south and east slopes; and of mixed hard woods—oaks, chestnut, maple, poplar, linn, and ash—associated with hemlock in the deep hollows and on north slopes. The better forests lie to the south of Mulberry Gap. East of this gap the oaks and pines are smaller and of poorer quality, and have suffered more from fires; but fires have also done much damage to the pines and oaks growing on the southward slopes. Culling has been carried on for many years, and much of the choicest timber has been removed from the bordering lands, even to the very sources of the streams; but much oak and some pine vet remain. The hardwoods reproduce freely from both stool shoots and seed, and the pines from seed. To prevent further deterioration of the forest and improve its condition, protection from fire is necessary, while improvement cuttings are required in many places to remove worthless stock and to free young timber. | ||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sen_doc_84/appa3.htm

Last Updated: 07-Apr-2008