|

The Land We Cared For... A History of the Forest Service's Eastern Region |

|

CHAPTER I:

THE REGION

Environmental Setting

The story of the formation of land, rivers, and forests in the northeastern quarter of the United States begins in the age of ice when nearly all of the region was covered by vast glaciers. The Ice Age began when the climate of North America became cold enough that more snow fell than melted. As the snow accumulated it compressed into ice, forming great domes, the weight of which forced the ice to move away radially. There were several ice domes or caps in North America and four or five glaciers that pushed onto the central plains. Those glaciers came from the Patrician Cap, located several hundred miles north of Lake Superior. The glaciers which affected New England came from the Labrador Cap far to the north of New England. [1]

Scientists believe that before the Ice Age the terrain of the region was much like those areas not affected by glaciers, such as the Ozark Plateau. Like other unglaciated-glaciated areas, its contour was formed by uplifts and domes which have been faulted and folded and then eroded by streams. Most terrain was vitally influenced by the type and contour of the underlying bedrock, but when the Ice Age came, a sheet or drift of rocks, sand, gravel and soil was laid down, its thickness determined by the number of glaciers and the contours beneath it. Obviously, the drift was thickest where there were valleys and thinnest where it lay over mountains. A drift thickness of several hundred feet was not uncommon in most of the Great Lakes areas. In the Hiawatha National Forest in northern Michigan, the drift is as thick as 1,100 feet. Since none of the glaciers extended that far south, National Forests such as the Mark Twain, Shawnee, Hoosier, Wayne, and Allegheny were not affected (See map on Maximum Extent of Glaciation in the Wisconsin Glacial Stage).

The major effect of the glaciers was to level the topography, cutting down hills and filling valleys. The glaciers left their deposits in moraines which resemble hills, but the terrain is less contoured than before glaciation; it is basically a plain. Scientists are not sure whether the glaciers created the Great Lakes. They generally believe the area was an interconnected lowland draining to the northeast before the Ice Age. [2]

Physiographic Divisions

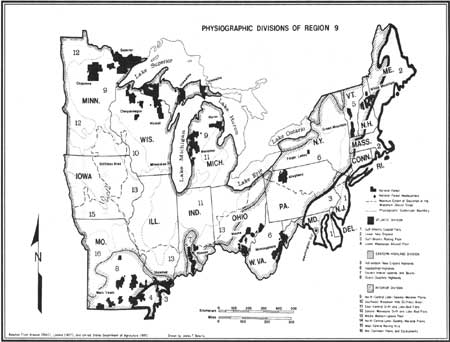

The land within the Eastern Region is divided into the following physiographic divisions: Atlantic, Eastern Highland, and Interior. Within these are subdivisions called provinces (See map "Physiographic Divisions of Region 9").

|

| Physiographic Divisions of Region 9. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The Atlantic Division includes the Coastal Flats Province, which extends from Cape Cod southward to the Chesapeake Bay. It is a monotonous coastal plain with broad, flat-bottomed valleys. Inland, the next province is the Gulf-Atlantic Rolling Plain or Piedmont. It extends from the Hudson Valley into southeastern Pennsylvania and central Maryland and is essentially a peneplain which has been uplifted, folded, and eroded. [3] None of the National Forests of the Eastern Region are in either of these two provinces.

Within the Eastern Highland Division are four provinces. The first of these, the Adirondack-New England Highlands, is essentially a basin which has been crumpled, faulted, thrust upward, and then glaciated and eroded. Two of the Eastern Region National Forests are found in this province, the White Mountain and the Green Mountain. [4] The Allegheny, Monongahela, and the Wayne National Forests are in the Appalachian Highland province.

|

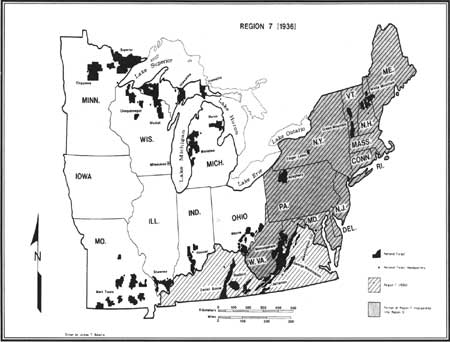

| Region 7, 1936. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The Ozark Highlands, although separated from the Appalachian Highlands by several hundred miles of plains, are generally considered a part of the same geological structures. The plateau was created by a great uplift dome, and it shows the topographical results of much faulting, folding, and stratification. [5] The Mark Twain and eastern parts of the Shawnee National Forests are in this province. The Hoosier National Forest lies largely within an extension of the Eastern Highlands Division known as the Eastern Interior Uplands.

Although the Interior Division has nine provinces, all of the eight National Forests in this division are within the North Central Lake-Swamp-Moraine Plains. The National Forests within this province are the Superior, Chippewa, Ottawa, Chequamegon, Nicolet, Hiawatha, Huron, and Manistee.

|

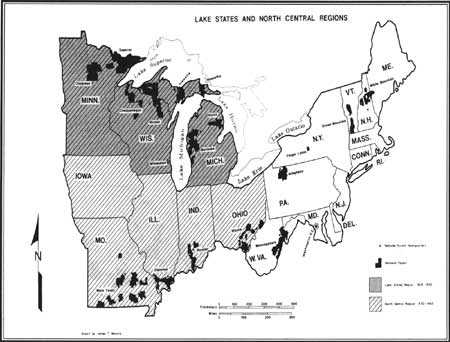

| Lake States and North Central Regions. (click on image for a PDF version) |

A physiographic analysis of the location of the National Forests of the Eastern Region illustrates the underlying determinants of land use patterns in the Region. The heavily forested areas of the northern Great Lakes and the Ozark and Appalachian highlands were never as profitable for agriculture as the rich lands of the southern Great Lakes area or the piedmont and coastal plain areas or the East Coast. In these same rich agricultural areas grew the first great cities and industries of America. Thus the ecological structure of the Region shaped land use patterns and population growth. The same determinants also dictated where the National Forests would be located. None of them were established in the heavily populated areas east of the Appalachian Mountains, along the southern shores of the Great Lakes, in the rich agricultural lands of the Midwest, or in the older, settled areas of Pennsylvania and upstate New York. All of them are in the northern Great Lakes and highlands areas.

|

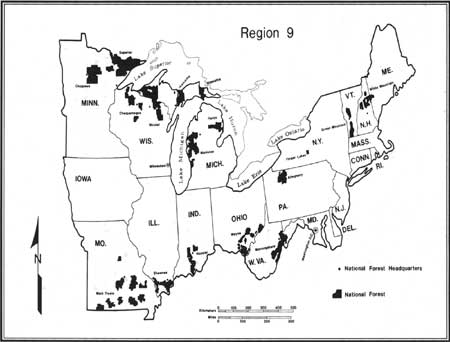

| Region 9. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Climate

The climate of the Northeast is affected by the Allegheny Mountains. The area having the greatest precipitation coincides with the high part of the Appalachian plateau which lies east of and parallel to the Allegheny front. Rains in the area usually come three to seven days apart and last one or two days. Local storms during the summer often last for only a few hours and sometimes bring as much rain as one inch. Such rains can result in flash floods and erosion damage.

The area of greatest snowfall is much the same as that of most rainfall. Snow seldom accumulates on the ground throughout the winter except in altitudes above 3,000 feet. Heavy rains in early spring often melt snow rapidly at high elevation and cause spring floods. [6]

All of the Eastern Region is in the temperate climatic zone. The length of growing season ranges from 210 days per year along the Atlantic Seaboard to 90 days per year in the far north where the Hiawatha, Green Mountain and White Mountain National Forests are located. The plant hardiness zones range from Northern Minnesota (where the Superior National Forest is located) where the temperatures drop as low as -50° F; to the relative balmy zone of Maryland and southern Illinois, where the average minimum temperatures are from 0° to 10° F. Naturally, the climates of the higher elevations of the Appalachians and Adirondacks call for hardier plants. There the minimum temperatures average -40° to -30°. Most of the Appalachians and interior areas have minimum temperatures of 30° to 0°.

Overall, the Region has a humid climate. Precipitation in the Region is less in the northwest and greater in the east and highlands. The annual average rainfall in the Chippewa and Superior National Forests is between 24 and 32 inches. At the higher elevations in the Appalachian ridges, the Green Mountains, the Catskills, and the Poconos, the climate is considered super-humid. Precipitation averages 24 to 40 inches per year in the Region west of the Appalachian Mountains. In some mountain areas, it is well into the 40s and at higher altitudes reaches as high as 74 inches, which is the precipitation average in the White Mountain National Forest. [7]

Forests

The hardwood forests of the northeastern United States are unique in the world. For sheer sylvan beauty, they are unsurpassed. However, the eastern forests are not all one type. The northernmost of these forests are in the transition forest zone which lies between the boreal—the cold and slow growing forests such as those of Canada—and the deciduous forests of warmer climates. The transition zone, is about 150 miles wide, extending from Minnesota to New England. In it the conifer species of the boreal forest mix with the hardy deciduous species. The zone is filled with a system of large lakes, but in New England, the forests extend to high elevations and even to the summits of rounded mountains and ridges. In the transition zone, the dominant tree is the sugar maple, which can crowd out spruce, fir, pine, and hemlock. Usually, however, the sugar maple associates with such deciduous trees as yellow birch, poplars, and basswoods.

From the Great Lakes to the southern extent of the Region is the deciduous forest zone. These forests once completely covered the Northeast with a veritable explosion of species—well over a 100. The sugar maple no longer dominates but rather mixes with the yellow poplar, sycamores, sweetgum, oaks, yellow birch, and in the southernmost areas, magnolias. Sugar maple associates primarily with American basswood in the northwestern part of the Region, in the Chippewa, Superior, Chequamegon, Ottawa, Nicolet, Hiawatha, Manistee, and Huron National Forests. While oaks and hickories exist throughout most of the deciduous forests, they tend to concentrate in the Ozark Highlands. Along the southern part of the Region, such as in the Monongahela, Wayne-Hoosier, Mark Twain, and Shawnee National Forests, the deciduous forest achieves its peak in age, maturity, number of species, size of individual trees, and area preserved in virgin state. The cove hardwood forests (sheltered, bottom land areas growing species like yellow poplar in ravines and hollows of the Appalachian and Ozark Mountains) provide, even in this modern world, a living museum illustrating the evolutionary development of the eastern forests after millions of years. [8]

There is a timelessness about the eastern forests. One estimate is that they are at least 75 million years old. If modern-day foresters could go back 70 million years and wander through the forests of New Jersey, they would feel quite at home in the 200 varied species of pine and deciduous trees they would see, including varieties of willow, poplar, beech, elm, mulberry, sassafras, grape vines, and the Virginia creeper. On the ponds floated water lilies, much as they do today. Even the mighty oak tree had its ancestors in these ancient forests. [9]

This great expanse of hardwood trees and pines was a new experience for the Europeans who came to explore and settle North America. The Europeans could recognize some trees they had known in Europe, such as beeches, oaks, and elms, but the American species of these trees were obviously different. Completely new to Europeans were white oak, hickory, dogwood, wild cherry, witch hazel, sassafras, walnut, sweet birch, and cranberry. Plants such as these exist only one other place in the world—Eastern Asia. [10]

Scientists today believe that Sir Francis Bacon was correct 300 years ago when he postulated a theory of drifting continents. During geological time, the continents have moved across the face of the earth. If the theory is true, Asia and North America could have been part of the same land mass originally. Plant geographers have come to accept the theory that millions of years ago, a hardwood forest evolved at the base of the Himalaya Mountains and spread eastward, forming a partial ring below the North Pole. About 50 million years ago, the land masses shifted, and the Ice Age began. The great glaciers of the Ice Age pushed the forests southward into all continents in the Northern Hemisphere. In Europe, where the ice pushed the forests against the Alps and Caucasus mountains and could go no further, the forests were covered by ice and destroyed. New species of these trees evolved later. Since the important mountain ranges of North America run essentially north and south, the forests spread as far south as climate would allow into Canada, Greenland, and the northeastern United States. There they remained and prospered, changing very little in the past 75 million years. [11]

Forest Types

Forest types are determined by the species of trees that predominate. In lower New England forests (Province 2, Division I), the dominant species are white-red-jack pine and spruce-fir. In the southern part of the province are oak-hickory forests. The Atlantic coastal flats (Province 1) are a mix of loblolly-shortleaf pine, oak-pine, and oak-hickory with a smattering of elm-ash-cottonwood. The Gulf-Atlantic rolling plain (Province 3) is largely hickory-type forest. The Gulf rolling plain in southeastern Missouri and southern Illinois (where parts of the Mark Twain and Shawnee National Forests are located) have oak-gum-cypress, oak-hickory, and oak-pine dominant forests.

In the Eastern Highlands Division, the Adirondacks-New England Highlands (Province 5) have spruce-fir forests in the north mixed with maple-beech-birch forests to the south. Some pockets of white-red-jack pine and spruce-fir forests exist. The Appalachian Highlands (Province 6) are largely oak-hickory forests in the south with some oak-pine at the higher elevations. In New York and northern Pennsylvania are oak-pine, maple-beech-birch, and white-red-jack pine forests and, along the southern shore of Lake Ontario, some elm-ash-cottonwood forests. In most of the Ozark Highlands (Province 8) the forest types are oak-hickory with oak-pine occupying portions of the northeastern Ozarks.

The Interior Division has a great non-forest zone which extends from central Ohio to Iowa and southern Minnesota. At its widest, this zone spreads from Green Bay, Wisconsin, to central Illinois. Large parts of the east central drift and lake-bed flats (Province 11), the middle western upland plain (Province 13), and the driftless area (Province 10) are lands that either never supported forests or which is now developed for other uses. To the south of this non-forest belt, the forests are predominantly oak-hickory with a large maple-beech-birch forest in southwestern Indiana. Along the rivers are forests of the elm-ash-cottonwood type.

North of the non-forest area is a mixture of forest types. In southern Michigan, northwestern Wisconsin, and central Minnesota, the forests are mostly oak-hickory. Northward are great forests of white-red-jack pine, maple-beech-birch, and elm-ash-cottonwood. In the far north are many maple-beech-birch forests, especially along the southern shore of Lake Superior and the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. This also is the empire where the great aspen-birch forests exist along with the spruce-fir, and white-red-jack pine types. [12]

Forest types are determined by the species of trees that predominate. For instance, the Adirondacks-New England highlands have spruce-fir in the north mixed with maple-beech-birch forests in the south. These will be detailed in the final work for all of the areas of the Eastern Region where there are National Forests. Other indigenous plant and animal life of National Forest System will be examined briefly.

Wildlife

The far northern and highlands forests of the Region are the home of many insect eating birds, the most common of which are the yellow-bellied and olive-sided flycatchers, tree swallows, and warblers such as the northern Parula warblers. The mammals of these areas are shy and nocturnal creatures such as the river otter, porcupine, muskrat, marten, fisher, ermine, bobcat, and beaver. The largest mammals are the moose; also seen are lynx, snowshoe hares, wolverine, black bear, gray wolf, and caribou.

Throughout the Great Lakes and New England forests, where the food chain depends largely on seeds and leaves, gray squirrels flourish in the deciduous forests and red squirrels in the coniferous woods. Grosbeaks, finches, buntings, towhees, siskins, juncos, and sparrows consume large quantities of seeds. The greatest consumer of leaves is the white-tailed deer. They browse so much of the new growth that it damages the forest and affects the patterns of development. Porcupines consume conifers to the point of occasionally killing a tree by girdling it. Cedar waxwings flock to any source of fruit. Insects abound in the forest, but so do insect eaters such as the tiny ruby-crowned kinglet and multiple species of warblers, chickadees, nuthatches, orioles, and tanagers.

In the deciduous forests of the southern part of the Region, the rich environment of the forest floor is a beehive of animal activity. Frogs, toads, and salamanders feed on insects and are in turn eaten by the predators of the forest, the snakes, skunks, and raccoons. Many of the insect-eating birds of forests to the north migrate to these forests to nest when the insect larvae are emerging in the spring. The mammals of these forests include the black bear, elk, white-tailed deer, red fox, woodchuck, gray squirrel, red squirrel, opossum, bobcat, and originally bison. This is the home of the cardinal, blue jay, wild turkey, and many varieties of owls, hawks, and water birds. Migratory ducks and geese often spend the warm months in these areas. [13]

History of the Region

Early People

Americans hunted the now extinct mastodon and a larger Ice Age bison and gathered wild plant foods in a zone near the face of the glaciers. When the glaciers receded, the flora and fauna associated with colder climates disappeared. Food resources shifted to the white-tailed deer, acorns and hickory nuts, and a wide variety of other plant and animal resources which began to adapt to the warming climate.

A long prehistoric period followed the early Ice Age hunters which can be characterized by an increase in cultural complexity. Small hunting and gathering societies evolved into more complex societies. Subsistence activities began with the collecting of wild plant and animal foods and culminated with the domestication of the three major New World crops—corn, beans, and squash. Human population increased and tended toward denser settlement patterns reaching its highest level from A.D. 1100-1500.

The archaeological record within Region 9 reflects this cultural development. Representative sites include the Itasca Bison Kill site near the Chippewa National Forest, the Rogers Shelter in western Missouri near the Mark Twain National Forest, and the Meadowcraft Rock Shelter in western Pennsylvania near the Allegheny National Forest. [14]

Indian Removal

The history of the two-century war between the white settlers of the Region and the Indian tribes who occupied it was a dark and bloody struggle which casts little glory on either side. Generally, it is a story of encroachment of white settlements, Indian resistance, wars and campaigns by the United States Army to repress the Indians, and eventual removal to places farther west through a process of forced treaties. In the end, what was called "the Indian problem" was solved to the satisfaction of the white population by taking the Indians' lands away from them and putting them on small, out of the way reservations, where many of them remain today.

The major Indian tribes of the Region were the Iroquois, Huron, Ottawa, Shawnee, Delaware, Wea, Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Miami, Winnebago, Sauk, Fox, Illinois, Chippewa, Sioux, Illinois, Osage, and Pawnee. The smaller New England tribes were made virtually extinct by extremely harsh treatment by the New Englanders before the end of the colonial period. Many of the eastern Great Lakes tribes such as the Iroquois, Hurons, and Ottawas were pushed by war into Canada where they now have reservations. In the areas west of the Great Lakes, the Chippewa and the Sioux were confined by military action onto small reservations in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and South Dakota. Most of the other tribes were removed, often by force, to lands and reservations in Oklahoma. Today, some of the remaining elements of Indian culture in the Region are located on or near the Superior, Chippewa, Hiawatha, Manistee, and Huron National Forests, which have about 13 Indian reservations nearby and tens of thousands of Indians living in the general area. The Allegheny National Forest has several hundred Indians living on or near it. [15]

Economic Development

The general historical development of Region 9 is far too great an undertaking to cover in this work. The boundaries of what eventually became the Eastern Region were drawn for reasons other than historical. It is, therefore, difficult to approach the historical development of the Region with any sense of unity. For the historian, the Region breaks down into distinct regions: New England, the Middle-Atlantic areas, Appalachia, the Ohio Valley, the Ozarks, the Mississippi Valley, the Great Lakes area, and the Great Plains. Each of these regions has its own history and there is great variety from one to another—all the way from the pilgrim settlement of Plymouth to frontier Indian fighting in Minnesota and Civil War battles in the Ozarks.

There are, however, several historical factors which unify the Eastern Region. It is the part of the country which first industrialized and developed into a modern nation. The system of waterways was the key to the pattern of economic development. In colonial times, trade with the Indians and most trade with settlements away from the Eastern Seaboard, was carried on by water transportation. Early settlement tended to spread up the Hudson, Mohawk, Connecticut, Delaware, Potomac and Susquehana Rivers, down the Ohio River, and up and down the Mississippi. With the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, the entire Great Lakes region was opened to trade with Atlantic Coast trade centers, principally New York City. In the same way, the Pennsylvania Canal opened trade between Philadelphia and the Ohio Valley. Later, canals connected the Great Lakes to the tributaries of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, so that by the 1850's, thousands of canal, lake and river boats and barges carried the raw materials of the West and the manufactured goods of the East to their markets.

Trade centers, strategically located on the waterways, began to grow. Cities such as Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, Cleveland, and Buffalo developed on the southern shores of the Great Lakes. Along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers grew Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Saint Louis, and Minneapolis-Saint Paul. After the 1840's a growing network of railroads connected these trade centers and made possible the development of manufacturing and eventually heavy industry.

The steel industry which developed after the Civil War in the Pittsburgh area is a good example of how the rail and waterway system worked. The heavy iron ores of the Mesabi Range in Minnesota were carried by rail to Duluth and other Lake Superior ports, then shipped from there through the Great Lakes, to the southeastern shore of Lake Erie where ore was moved by river barge and rail to the Pittsburgh area. There the other ingredients for making steel were available—the coal of western Pennsylvania and coke from the local ovens. Finished steel products were then shipped east and west by rail and down the Ohio River and back through the Great Lakes.

By the turn of the 19th century the upper Ohio Valley had become one of the great industrial regions of the world. Much of what was produced sold in the rapidly expanding markets of the Midwest and Great Plains. Chicago, Minneapolis, and Kansas City became the suppliers of the needs of the great agricultural heartland of America and the processors of its products.

When the automobile developed, it was natural that Detroit, with its location on Lake Erie and its connections to the east-west axis of rail trade would become the manufacturing center. The national system of highways which developed for automobile and truck use in the 1920's and the Interstate Highway System of the 1950's served only to connect already established population and trade centers.

Geographical Determinants

Too much has been made by some writers of geographical determinism, but there can be no denying the importance of geographical factors on the economic development of the Eastern Region. The great cities and industrial areas developed along the southern shores of the Great Lakes, on the great rivers, and at the transportation crossroads. The lumber and other extractive industries developed in mineral and forested areas. Agriculture flourished in the fertile valleys and glaciated plains of the Lake States and the Great Plains. In the end, many forested areas were used and abandoned while others with little accessibility were undisturbed. These are the areas where National Forests were to be created, generally in the Ozark and Appalachian Highlands and the north woods country of the upper Great Lakes area. Stretching from the northeast to the west-central part of the Region is a broad belt of heavily developed area in which there are no National Forests today.

Political Development

Politically, the Eastern Region has been the most powerful part of the country. Because nearly half of the people of the United States live in the Region and most of the large cities are there, the Region has dominated national politics and elections. More presidents have come from this Region than any other and all major political parties have had to come to terms with the needs of the Region. Since the Civil War and well into the 20th century, the big business and Wall Street interests of the northeast have exerted strong political pressures on federal and state governments to the point of domination and sometimes corruption. Many of the reform movements of the modern era have been campaigns to break the power of the eastern industrial financial establishment and return control of government to popular majorities.

In terms of political affiliation, the rural areas of the Eastern Region have tended historically toward the Republican Party and the urban areas toward the Democrats. Cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Kansas City have had deeply entrenched political machines which controlled local politics and were power brokers in state and national elections. While these city machines were usually within the Democratic Party, there were comparable state political machines in some states which were usually Republican.

Generally speaking, the large states of the Region with big cities are mixed politically and can lean toward either party depending on the issues and the candidates. The states without large cities are traditionally Republican and are generally considered conservative. The cities, as a rule, have liberal tendencies.

Mining and Minerals

The general history of mining in the Region has many commonalties. Iron and lead mining developed in colonial times in New England and the Appalachian Highlands. Lead was mined in the early 18th century in Missouri and Illinois. In the 19th century, coal became the principal fuel of the new American industrial complex. A major source was the Appalachian Highlands and the Ohio Valley. After the Civil War, the iron ore for the steel mills of Pittsburgh and other steel centers along the Great Lakes came largely from Minnesota and Wisconsin. Much of the copper used by the growing American electrical industry came from Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and much of the lead for many industrial uses came from Missouri. Most of the world production of fluorspar, a scarce and strategically important mineral, takes place in or near the Shawnee National Forest.

Contrary to conventional interpretation, there were significant deposits of gold and silver in the states of the Eastern Region. Total gold production of approximately 100,000 troy ounces has taken place in Pennsylvania and lesser amounts in most of the other states. Even the non-mountainous state of Iowa has produced about 50,000 ounces. Silver production has been greatest in Missouri, where over a million troy ounces were produced in 1970. Silver mining extends from Maine to Wisconsin throughout the Great Lakes region.

Other major metals produced in the Region include copper, found in the Gogebic range in and north of the Ottawa National Forest and in scattered pockets in the Piedmont area of the east coast and New England. Lead has been produced since colonial times in Missouri (about one million short tons), Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania. Some of the lead mine areas of Missouri are in the Mark Twain National Forest. Zinc production has been highest in New York (over a million short tons), Wisconsin, Illinois, and Pennsylvania.

The most important metal mined in the Eastern Region has been iron. Minnesota is the leading state in the production of iron with more than 100 million long tons worth over $1 billion. Some of the major deposits are in the Superior National Forest. Wisconsin and Michigan iron production is almost as great, with important deposits in the Ottawa National Forest. A portion of the Missouri production of iron came from deposits in the Mark Twain National Forest. There has been significant production going back to colonial times in Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and in more recent times in Michigan, West Virginia and Ohio. [16]

The American oil industry, the first in world history, originated in western Pennsylvania. The Standard Oil Company of John D. Rockefeller achieved its near monopoly of the industry from its beginnings in Cleveland, Ohio. Until after the turn of the 20th century, what is now the Eastern Region was the world center for the production, processing, and distribution of oil. While the industry has moved to other parts of the country and the world, Pennsylvania lubricating oil remains the standard of the industry and important production and processing still takes place in the Region.

Lumber

The lumber industry in the Region began in New England and in the Middle Atlantic colonies during British colonial times. The forests of the area were important sources for ships' masts and naval stores for the British Empire. The Navigation Acts, Orders in Council, and numerous pieces of colonial legislation endeavored to protect and regulate the cutting of trees used in shipbuilding. The Great Lakes area, where the forests were so dense as to be virtually impenetrable by the ordinary 19th century frontier farmer, was the lumberman's empire. The great lumber companies and the famous timber barons of this age operated in the same areas that are managed today by the Forest Service in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, and other states.

Like other extractive industries, the lumber industry tried to consolidate and monopolize during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Lumber became big business, employing all of the ruthless practices of burgeoning American capitalism. There were monopolistic devices such as pools, trusts and holding companies. There were company towns, where exploitation of the workers mixed with paternalism and corruption of local and state governments and politicians. The lumber industry tended to operate in a cycle. In the early days there was very rapid economic growth, even boom times, followed often by decline and collapse when the forests had been cut and the lumber companies had moved away.

The Appalachian and Ozark Highlands and the northern Great Lakes plains were once covered with spruce-hardwood forests, but by the 1940's these areas had been generally logged. Only about 20% of the pre-European forests remained. The rest was covered with brush, slash from the cutting, and timber of poor quality. Fire was a great danger there. Scattered throughout the Region there remained a few isolated stands of hardwood and spruce, but there were few markets for the timber. [17]

Summary

The economic development of the Eastern Region was done largely by extractive industries. The great manufacturing complexes of the area fed on the coal, iron, oil, water, soil, and wood of the Region. These industries, along with advanced agriculture, helped to create great cities and change the face of the land. In the process they abused the natural resources badly and polluted the air and water. It was this situation which created the need for conservation in the United States and action by the federal government.

Reference Notes

1. Wallace W. Atwood, Physiographic Provinces of North America (Boston: Genn & Co., 1940), pp. 155-162.

2. William D. Thornberry, Regional Geomorphology of the United States (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1965), pp. 216-221.

3. Wallace W. Atwood, Physiographic Provinces, p. 75 and Frederick B. Loomis, Physiography of the United States (Garden City: Doubleday, 1937), p. 16.

4. William D. Thornberry, Regional Geomorphology, pp. 152-157, 160, 171-172.

6. General Integrating Inspection Report, R7, 1947, 95-A-0036, Philadelphia Federal Regional Records Center (PRC), RG 95.

7. Atlas of United States Trees (Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1971), Overlay 6-W

8. Ann Sutton and Myron Sutton, Eastern Forests (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1923), pp. 20-21.

9. Rutherford Platt, The Great American Forest (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1965), pp. 4-9.

12. U.S. Department of Interior, Geological Survey, National Atlas (Washington, 1970), pp. 154-155; and Atlas of American Trees, Vol. I.

13. Ann Sutton and Myron Sutton, Eastern Forests, pp. 38-40, 53-54, 65-67, 77-78.

14. Thomas C. Shay, The Itasca Bison Kill Site, an Ecological Analysis (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1971).

15. National Atlas, pp. 256-257.

17. USDA Forest Service, Office of the Chief, General Integrating Inspection Report, R7, 1948, 95A-0036, Philadelphia Records Center cited as, RG 95.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region/9/history/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 28-Jan-2008