|

The Land We Cared For... A History of the Forest Service's Eastern Region |

|

CHAPTER XV

THE MONONGAHELA CONTROVERSY

In 1964, the Forest Service unwittingly provoked a major national controversy over clearcutting which cast a shadow over its national image. The affair has come to be known as the Monongahela Controversy. It started when the Forest Service changed its method of harvesting timber in Eastern hardwood forests from partial to clearcuts. The change was based on extensive research which indicated that clearcutting was more productive in wood volume, produced trees which were more desirable, and yielded better wildlife habitat.

Unfortunately, the decision to adopt clearcutting was made without public involvement and with little explanation. Moreover, it was contrary to common practices of the timber industry in the East, and it was foreign to the management of eastern National Forests.

Apparently, the Forest Service had no idea that the policy of clearcutting might generate a dramatic public controversy. Clearcutting was common practice in the West where the clear-cut areas were usually separated by miles from highways and areas of habitation. However, people in the East were deeply shocked at the ugly sight of fresh clearcuts.

The common fear was that the land had been severely damaged, the biotic balance disturbed, and the wildlife habitat destroyed. The reasoning was often simplistic: What was once a stand of trees was there no more. Where was there a home for forest animals? Hunters who had used certain woods for years to hunt deer or squirrel were shocked to see their favorite places cut-over.

The Forest Service Research on clearcutting had failed to take into account the human element—the public reaction. Nor did it fully reckon with the differences between eastern and western forests.

Beginnings of the Controversy

On one eastern National Forest, the Monongahela, the zeal to implement the new policy meant large clearcut units and even large cuts next to each other. Then, to make matters worse, the Monongahela management decided to go to areas where heavy cutting had already taken place and remove the remaining trees. The Forest Service considered this to be nothing more than "an over-story removal operation," but to most people it looked like more clearcuts. In reality, it was.

Clearly, the managers of the Monongahela lacked sensitivity to what the public might think of the way the new clearcutting policy was implemented. Some of the clearcuts were made in very visible places and utilization of felled trees in some areas was extremely poor or not done. The Monongahela is like most Eastern Region Forests in that private lands are interspersed with National Forest lands and many roads run through the Forest areas. The effect of this situation on the Monongahela was that residents were able to see clearcuts out their kitchen windows. Sunday drivers in the National Forest received the impression that the Forest was being destroyed.

One aspect of the problem in the East was that the specter of clearcutting raised many old fears. There was deep concern by many people that a return to clearcutting in the East would bring again the disastrous events caused by clearcutting in the late 19th century. Floods like the Johnstown Flood and forest fires like the holocaust at Peshtigo came to mind. The Conservation Movement of several generations earlier had done such a good job of convincing the American public of the value of forests that most Americans believed any kind of clearcutting was a terrible mistake.

There was a general negative reaction to the new Forest Service policy and expressions of protest began to surface. The controversy assumed serious proportions in Maine, Texas, Idaho, and the Bitteroot National Forest in Montana, but it focused most sharply on the Monongahela National Forest. The reason was the aggressive leadership of local citizen groups by men such as Kermit Moore of Lewisburg, Howard and Lawrence Deitz at Richwood, and Don Good of Parsons. These men were neither professional environmentalists nor wilderness advocates. They supported multiple use and timber cutting, but they flatly opposed clearcutting. They and their groups received no direction from outside organizations such as the Sierra Club or the Wilderness Society. However, Moore and the Deitzs were members of the Izaak Walton League, and they used the local chapters of that organization as their forum.

When the local groups appealed to the Forest Service to stop the clearcutting, they were told in effect, that the Forest Service knew what it was doing; it had solid research to back up the decision. The groups went next to the West Virginia Legislature, where they received a more positive reception. The Legislature created a Forest Practices Commission which studied the problem and concluded that clearcutting was wrong. The controversy also reached the U.S. Congress when West Virginia Senator Jennings Randolph, feeling pressure from his constituents, began raising questions about clearcutting on the floor of the Senate.

The Monongahela staff and line officers tried to counteract the unfavorable public reaction by hosting many open houses and tours. They tried to show the benefits of the new policy and to educate the public in the values of clearcutting, but they made little headway.

The Izaak Walton League Case

In the early 1970's, the U.S. Congress passed guidelines for clearcutting proposed by Senator Frank F. Church of Idaho. But before these could be implemented the whole affair reached a climax in 1972 when the Izaak Walton League and others sued the USDA and the Forest Service. The suit claimed that clearcutting violated the Organic Act of 1897. This Law required that only individually marked, mature or dead and dying trees could be cut. The trial was held in federal court in Elkins, West Virginia, the headquarters of the Monongahela. Judge Robert Maxwell found that the Forest Service was violating the Organic Act by clearcutting and set up some guidelines on how timber would be offered for sale by the Forest Service. Generally, sales were to be according to the Organic Act's provision that only mature trees could be cut. The problem with this was that there were virtually no mature hardwood trees on the Monongahela. Widespread logging around the turn of the century had taken the mature hardwoods. Second-growth trees of the Monongahela would not be fully mature for many years. The Forest tried to make some timber sales under the court guidelines, but the lumber industry virtually laughed at the offers. They simply were not marketable.

Realizing that the court guidelines were impossible to follow, not only on the Monongahela National Forest, but also on all other National Forests, the Forest Service decided to appeal Judge Maxwell's decision. They took the case to the Fourth Circuit Court which covers Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. That court upheld Judge Maxwell's decision, saying that no other interpretation could be put on the existing laws. In effect, this decision put the Forest Service out of the timber sales business in those four states, but, even worse, it opened the door for similar cases in other federal courts. The Forest Service faced the prospect of the end of clearcutting nation-wide.

Congress Takes Action

The crux of the problem was that the Organic Act was written before modern forestry and before creation of the National Forest System. It was obviously time for Congress to take up the problem, which it did in 1973. There were two possible courses of action: prescriptive legislation which would tell the Forest Service exactly how to cut timber, or a planning approach which would require the Forest Service to determine the issues, involve all of the interested publics, develop a balanced plan, and follow the plan. Senator Jennings Randolph of West Virginia was the leading proponent of the prescriptive approach and Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota led the planning advocates.

RPA and NFMA

Humphrey and the planning approach won out, and Congress passed the Resources Planning Act (RPA) of 1975. This Act led the way to the National Forest Management Act (NFMA) of 1976, which mandated the development of forest management plans for all National Forests. These laws permitted clearcutting on National Forests only where it had been shown to be the best forestry practice and only after all interested parties had been given an opportunity to react.

The local controversy over clearcutting which had begun on the Monongahela had grown to be a national issue and had brought about a major change in the Forest Service. It is also clear that the Service learned some valuable lessons from the Monongahela Controversy. The old days when the Service managed the forests as it saw fit—almost like a private corporation—were gone forever. The American public of the 1970's and 1980's was vitally interested in what was done with their National Forests, and the Forest Service would have to let them in on the decision making process.

The RPA and the forest planning process which followed it did not end the clearcutting controversy. There remained various vocal and active groups and individuals who were adamantly opposed to clearcutting anywhere and under any conditions. By now the Forest Service has found ways to return to carefully planned clearcutting, even though they expect protests from certain predictable groups and organizations every time it is done.

Life After Controversy

As for the Monongahela, it was back in the timber sales business by 1978. Under the RPA, the Forest prepared an Environmental Impact Statement, presented it to the public, and resumed cutting according to the approved plan. This time, however, the Forest Service learned its lesson. Under the new guidelines, clearcuts were limited to 25 acres in size. They had to be separated by at least an eighth of a mile. They would have an irregular perimeter which followed the landscape. And before a cutting unit could be made next to an older one, the older cut had to be regenerated to the point that the trees were 20% of the height of the surrounding forest. These rules which have been used since 1978 have been generally well received, not only by people in West Virginia but by many in the forest products industry. They have been written into the Monongahela Forest Plan, which was implemented in August 1986.

Today, the Monongahela harvests about 1,300 acres of forest per year by clearcutting. There has been no recent organized protest. Some complaints have been received, but these are about a particular clearcut which has ruined a favorite hunting place or affected the view from a summer home. The lessons learned in the Monongahela Controversy have been disseminated throughout the Forest Service. All other forest plans are presented to the public in the planning and implementation stages. Clearcutting may be included in any of them, but it is carefully regulated. The Forests expect protests from wilderness and anti-clearcutting groups but they are now able to deal with them as a result of the Monongahela Controversy and the legislation which came out of it. [1]

The Monongahela has received only one formal appeal to its Forest Plan as of July 30, 1986. It was from John R. Swanson of Minneapolis, Minnesota, and it protested that insufficient areas had been allocated for wilderness purposes. Swanson filed the same kind of appeal to every forest plan in the Region. Unofficially, the timber industry let the Forest know that it was not happy with the low levels of harvest and that too much land had been taken out of production by placing it into categories where habitat or recreation would be emphasized. This was not a protest for or against clearcutting, but rather a move on the part of the industry to be allowed to harvest more timber throughout the Forest.

The Monongahela is not likely to yield to the timber industry and allow more cutting on the Forest than has been put in the Forest Plan. The Forest managers are now quite sensitive to the desires of the various publics. The Forest had a heavy response from the public to the draft forest plan—3,597 letters signed by about 17,000 people and containing about 35,000 ideas. Basically the respondents wanted less emphasis on commodities, less road construction, no leasing for coal, better habitat for bear and turkey, dispersed recreational opportunities, protection of scenery, and conifers managed for habitat rather than for lumber. The Forest staff carefully analyzed these responses and tried faithfully to incorporate the basic ideas into the Forest Plan. In its final form, the Plan contained 80,000 acres of wilderness, (about 9% of the Forest), 125,000 acres without harvest for recreation use (about 15% of the Forest), and about 75% of the Forest in remote habitat where there would be carefully controlled harvesting and very few roads.

The protest of the timber industry about so much being given to wilderness and recreation was seriously blunted by the fact that the Monongahela supplies only 10% of the Forest stock for harvesting in West Virginia. Obviously, the short range economic impact on the industry would be minimal. During the years when the Monongahela was literally out of the timber business in the mid-1970's because of the clearcutting Controversy, the West Virginia timber industry continued operating normally, and avoided becoming involved in the Controversy.

The main concern of the timber industry, as expressed to the staff of the Monongahela, was that the restrictions placed on timber cutting by the Forest Plan might threaten their ability to expand in the future. However, these fears were probably unwarranted. The Forest, which presently produces approximately 40 million board feet of wood per year, has the potential to produce 400 million board feet sustained yield. However the public reaction to the draft forest plan, as interpreted by the Forest staff, clearly showed that the public did not want that kind of production; therefore it was not written into the Plan. If the need for more timber should arise someday, the Forest Plan could be revised by the same processes as the original Forest Plan, including obtaining public reaction.

The stories are much the same on all National Forests, and this is part of the beauty of the forest planning process. The Forest Service is now in the position of acting as arbitrator for all the various interest groups but always with the idea that the general interests of the public must be served. No longer is it valid to charge that the Forest Service serves only the interest of the government or the timber industry. By the same token, it is not unduly influenced by the wilderness advocates. [2]

The Regional Office in the Controversy

The reaction to the Monongahela Controversy in the Regional Office was slow at first and then, when the matter gained national importance, it seemed that in the Regional Office they had no time for anything else. Regional Forester Jay H. Cravens remembers that when he and new Forest Supervisor Tony Dorrell came to the Region in 1969 the Monongahela Controversy "was waiting" for them. From a Forest Service policy standpoint, it was probably something which could not have been avoided. Clearcutting was a well established practice. The older practice of selective cutting had fallen into disfavor because it had become a process of high-grading the Forest, that is, cutting only the most valuable trees. The high-grading had reached the point that the regeneration of desired species was not always taking place.

In the instance of the Monongahela National Forest, multiple use planning had not been done and there was little experience in timber marketing, especially pulpwood. To make matters worse, there was also little awareness of the effect that clearcutting might have on the local population. Forest Service Research clearly supported even-aged management including clearcutting and while some of the clearcuts made on the Monongahela were large and executed in sensitive areas, and had poor utilization of pulpwood that was cut, they were generally biologically sound. The problem was that they were not politically sound or acceptable in the new environmental climate.

When the public protest against the Monongahela clearcuts began to appear, the reaction in the Regional Office was much the same as that of the Forest. The attitude was "we know what is best since we are looking at the long range results." Then, when the criticism accelerated, the Region encouraged the Forest to make changes which would answer some of the criticism. By this time, however, the matter had become a national issue and could not be quieted by half-measures.

Regional Forester Cravens remembers a conversation he had at this time with Michael Frome, a leading critic of the Forest Service. Frome told Cravens that he fully realized that the Region, the Monongahela, and the Forest Service had made changes in response to the Monongahela Controversy and that they were clearly demonstrating their sensitivity to the need for change, but it did not suit his purposes to write about it at that time. Says Cravens, "That hurt!" He realized, however, that the Forest Service was on the defensive and would probably have to do much more changing before the criticism would be silenced. [3]

Reference Notes

1. Gilbert Churchill, Interview, July 30, 1986)

3. Jay H. Cravens to David E. Conrad, 1987.

|

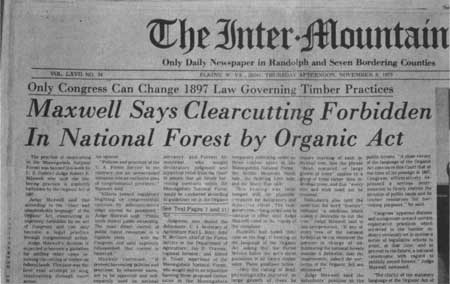

| Monogahela National Forest clearcutting issue, Inter-Mountain, newspaper, Elkins, West Virginia, November 8, 1973. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region/9/history/chap15.htm

Last Updated: 28-Jan-2008