Looking at Prehistory:

Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 12,000 B.C. to 1650

|

|

Looking at Prehistory:

Paleoindian Period: ?12,000 to 8,000 B.C.

Paleoindian peoples are represented by several

cultures. Scattered sites and tools from many of these have been found

in southern Indiana, but most Paleoindian sites are quite small with few

tools and other remains to inform on their lifeways.

Clovis culture is the best known of the Paleoindian

period and was a successful hunting tradition that emerged from the

first peoples to enter the New World from Siberia. The first peoples

probably entered North America along the Pacific Coast and through the

interior of Alaska thousands of years earlier perhaps when massive

glaciers of packed snow were beginning to cover the land causing ocean

levels to drop three hundred feet lower than they are today. The Clovis

culture developed probably several thousand years after people were

already actively exploring the New World. Clovis people apparently lived

in small groups and moved their camps frequently in search of game and

plant foods.

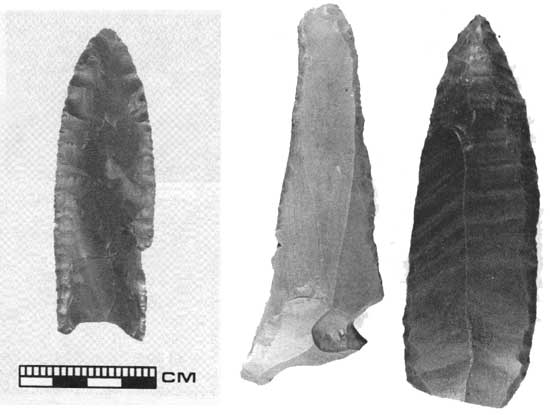

Clovis hunting camps and tool manufacturing sites are

distributed from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from Alaska to Florida

across all types of landscapes. The basic Clovis tool kit includes the

distinctive Clovis type projectile point, along with large bifacially

flaked tools and unifacial blades for butchering game, and side scrapers

and end scrapers for cleaning and preparing hides for clothing and

shelter (Figures 17-18). They also used bone, antler and ivory for tools

made from the animals they killed, but these are not often preserved

except in wet sites, such as springs in Florida and Arizona and frozen

sites in the Arctic in environments where bacteria and other organisms

cannot destroy the evidence. So far, no perishable Clovis artifacts

have been found in Indiana, but many Clovis

projectile points and other stone tools have been collected, indicating

this part of North America was just as important as other areas for

Clovis survival and settlement.

|

|

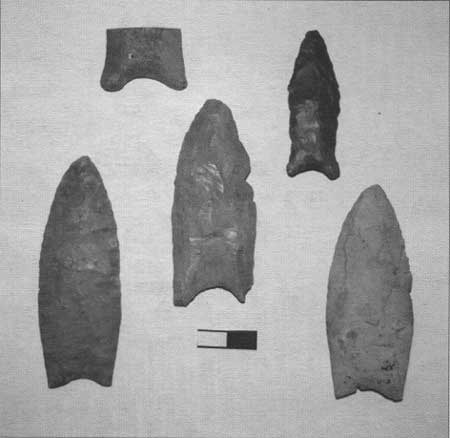

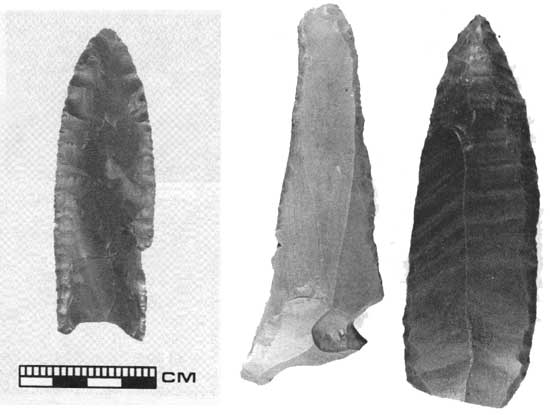

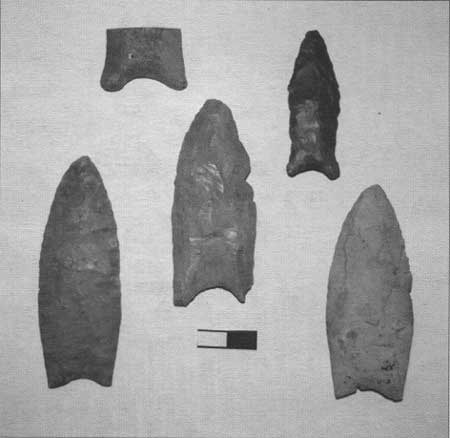

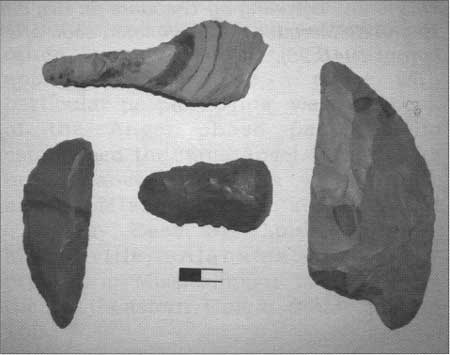

Figure 17: Clovis and later Paleoindian period Quad

and Beaver Lake projectile points from sites in southern Indiana. The

Clovis point shown in the lower right was recently recorded and donated

to the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology.

|

|

|

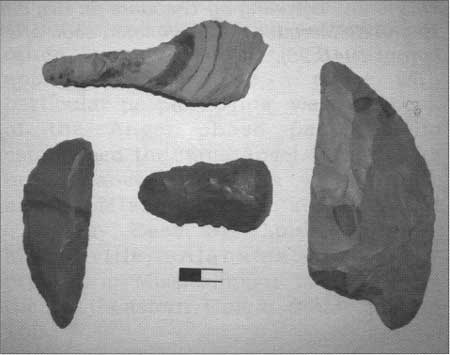

Figure 18: Tools used during the Paleoindian period.

These include an end scraper, side scraper, unifacial butchering knife,

and "rat-tail" tool (above) perhaps for hafting into a handle for use as

a scraper.

|

The environment in Indiana at the close of the Ice

Age was much colder than today. Studies of pollen preserved in mud and

peat in the bottom of ancient ponds and lakes show that spruce and pine

forests covered much of the land with intervening open steppe-like

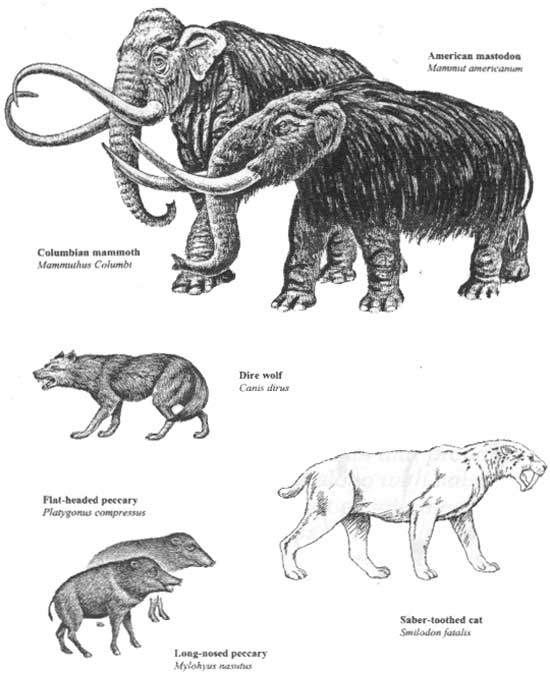

grasslands. This environment was home to the mastodon, mammoth, musk

ox, ground sloth, caribou, dire wolf, peccary, saber-tooth cat and a

variety of smaller game animals (Figures 19-20). By about 8,000 B.C.,

the glaciers that once covered the Midwest had melted back into Canada

and basically all of the larger animals were extinct by the time the

environment finally changed to the hardwood forest of today. Animals

such as the caribou and musk ox still survive in the far north

today.

|

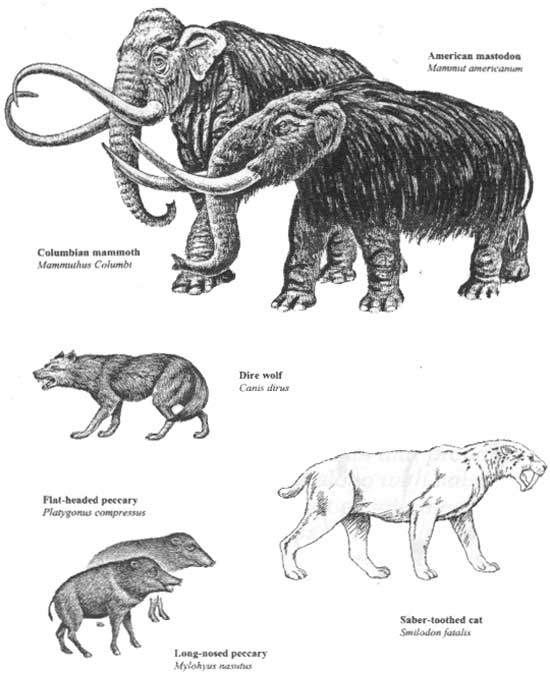

Figure 19: Ice Age Animals including mammoth,

mastodon, dire wolf, two types of peccary, and saber-toothed cat. All of

these animals went extinct at the end of the Ice Age (Modified from

Lange 2002: 95, 106, 161, 167).

Columbian mammoth

Mammuthus Columbi

American mastodon

Mammut americanum

Dire wolf

Canis dirus

|

|

Long-nosed peccary

Mylohyus nasutus

Flat-headed peccary

Platygonus compressus

Saber-toothed cat

Smilodon fatalis

|

|

|

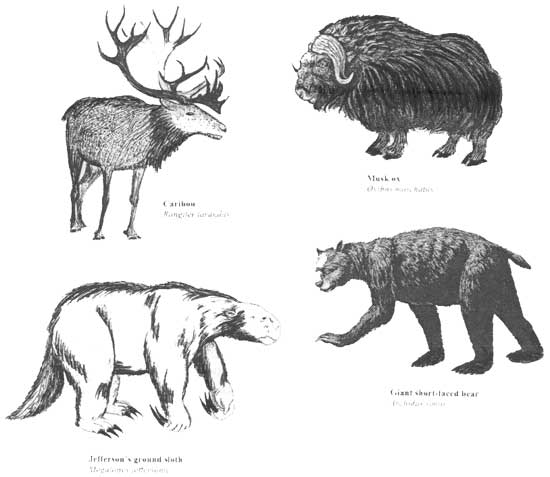

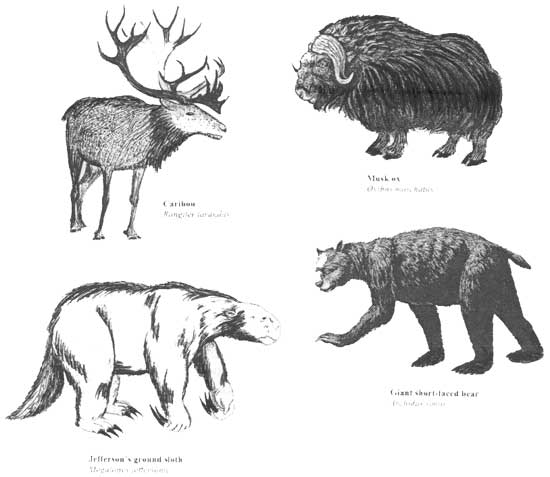

Figure 20: Ice Age Animals including caribou,

musk ox, ground sloth, and giant short-faced bear. The ground sloth and

giant short-faced bear went extinct at the end of the Ice Age. Musk oxen

and caribou still live in the arctic today (Modified from Lange 2002:

83, 101, 148; and Pielou 1991:145).

Caribou

Rangifer tarandus

Jefferson's ground sloth

Megalonyx jeffersonii

|

|

Musk ox

Ovibos moschatus

Giant short-faced bear

Arctodus simus

|

|

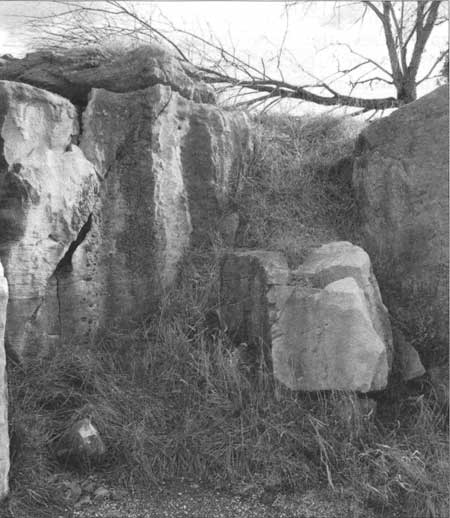

The hill country of south-central Indiana

encompassed by the Hoosier National Forest is a very unique part of

Indiana (Figure 21). This region is known for its caves, crevices, and

other natural traps where now extinct animals entered and eventually

died. Their bones accumulated with sediments, leaving an important

record of the natural history of the region. Some of these include the

Harrodsburg Crevice and Knob Rock Cave in Monroe County and Megenity

Peccary Cave in Crawford County. The remains of giant ground sloth, dire wolf,

peccary, saber-tooth cat, and other extinct animals have been found in

these natural traps and pit caves (Figure 22).

|

|

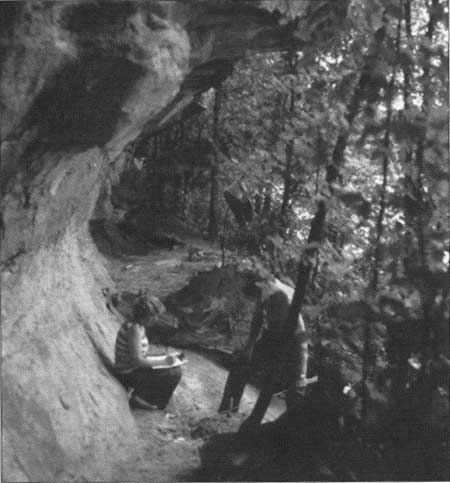

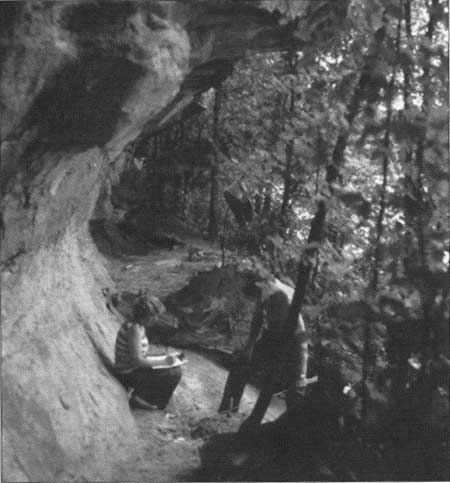

Figure 21: A small rockshelter overlooking the Salt Creek Valley, Monroe

County, IN. Investigations determined the shelter to be a shallow and

disturbed accumulation of sediments that contained evidence of sporadic

use during the Archaic period. Interestingly, the site also contained

small fragments of preserved bone and charcoal. Some of the bone is

thought to be Pleistocene in age and could have been left in the shelter

by Ice Age predators. Indiana University field school, 1978.

|

|

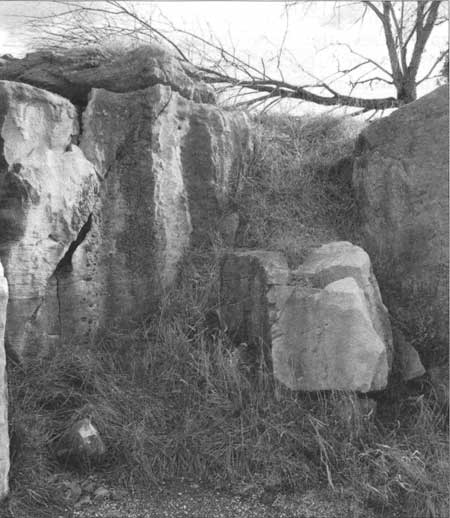

Figure 22 (left): An entrance to Harrodsburg Crevice now covered by soil

and grass (Photo by the author). The crevice extends to an unknown depth

and may connect with a large cave system. During the Late Pleistocene

(Ice Age), solution cavities formed within the Salem Limestone and some

with steep walls became natural traps from which unfortunate animals

could not escape.

The Harrodsburg Crevice has produced the remains of fossil animals

including saber-toothed cat, peccary, dire wolf, black bear, coyote, and

wood rat. Wood rats probably lived within the crevice and may have

scavenged and brought in some of the bones. On the other hand, peccaries

were large animals and probably were trapped along with saber-toothed

cat that sought them as prey. An open grassy landscape with patches of

trees probably existed at the time the animals died in the crevice

during the period between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago (Volz 1977).

|

While Clovis kill sites of mastodon and mammoth are known from widely

scattered sites in the United States, none have been

found so far in Indiana. Kill

sites are those that have animal remains with stone tools among bones

and sometimes a small campsite where tools were made and resharpened

around a fire. The kill site is often at a spring or pond where perhaps

the large animals died after being wounded with spears some distance

away. Finds of mastodon bones are relatively common in the ponds and

gravel pits around the state and we can expect some archaeological

surprises in southern Indiana if such finds are reported to the

archaeological community before they are disturbed or looted (Figure

23).

|

|

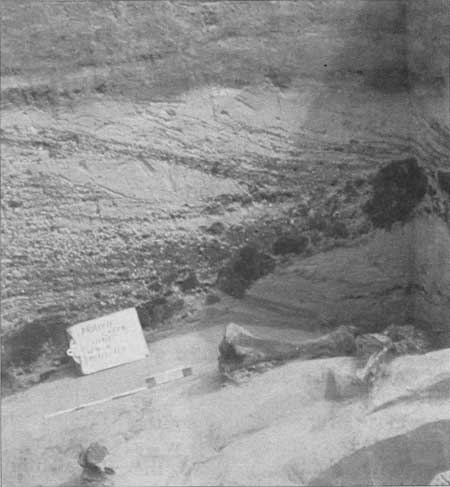

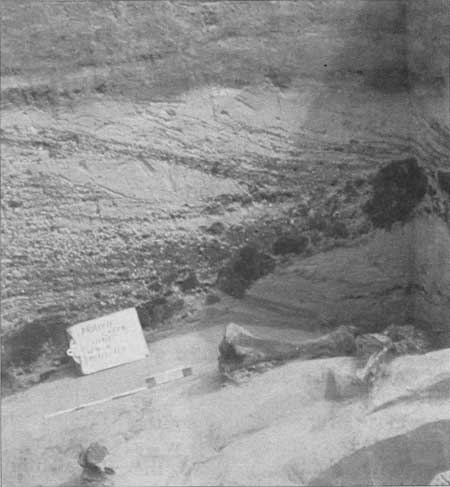

Figure 23 (right): Mastodon bones exposed within the sediments of

Prairie Creek, Daviess County, IN. Reports of finding large animal bones

by the landowner in 1974 prompted archaeologists to investigate the

site. The excitement of perhaps having found a buried Clovis site led to

two seasons of excavations where many detailed stratigraphic maps were

made of the creek bank deposits and more scattered mastodon bones were

unearthed. After careful study of the creek bank, it was concluded that

thousands of years of flooding had caused Prairie Creek to cut and

refill repeatedly since the Ice Age. The mastodon bones had been moved

and scattered by the creek perhaps many times before coming to rest

where the archaeologists found them. The few prehistoric tools that were

found date to the Middle and Late Archaic periods and these were found

in redeposited soils above those containing the mastodon bones. Indiana

University field school, 1975.

|

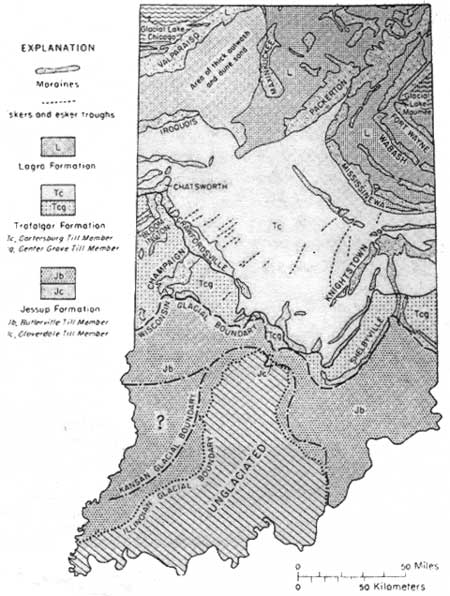

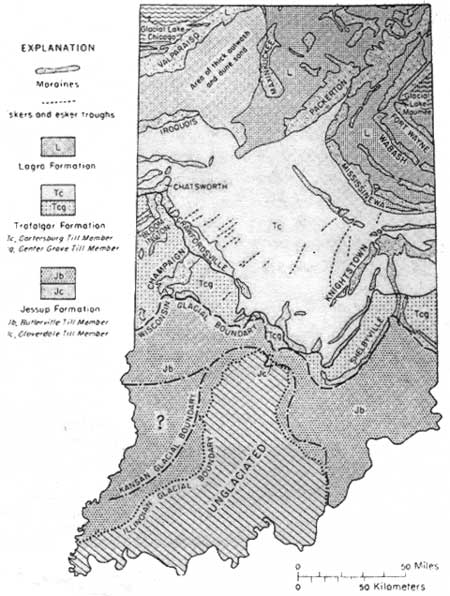

At least some of the steep ravines and hollows of the

Hoosier National Forest may have been used as natural surrounds by

Clovis hunters to trap and kill game and make winter camps that would

have been at least partly protected from the wind and cold of the

Arctic-like conditions they endured. We know from geological and pollen

studies that southern Indiana was not covered by glaciers during the

last Ice Age (Wisconsin) between about 19,000 and 13,000 B.C. Even

earlier glaciers by-passed the hill country of south-central Indiana

providing a unique refuge where ice age plants and animals survived when

the rest of Indiana was covered by thick glaciers that had advanced out

of Canada and the Great Lakes area (Figure 24). Therefore, at the close

of the Ice Age, south-central Indiana was environmentally ahead of the

rest of Indiana as the changes

away from Arctic-like conditions slowly gave way to a

warmer climate. The kinds of plants and animals that we are familiar

with today took the place of the Arctic species earlier here than in

northern Indiana.

|

|

Figure 24: Map of Indiana showing the extent of

Ice Age (Pleistocene) glaciations (From W. J Wayne "Ice and Land" in

Lindsey 1966: Fig. 8).

|

During the very long process of glacial melting due

to the change in climate, the major river valleys such as the Ohio,

White and Wabash were formed by carrying large amounts of cold glacial

meltwater. The glaciers deposited tremendous amounts of sand, gravel,

and soil within the river valleys and across the land. The glaciers also

formed the landscape over much of Indiana including the many hills and

moraines (e.g. wide, parallel lines of hills marking where glaciers of

ice advanced and then melted back). Plowed fields in

northern Indiana often contain thousands of rounded

and flattened rocks of all sizes that were carried down from Canada by

the glaciers. Glacial melting also caused tributary streams and lowlands

to be flooded creating wide waterways and lakes that eventually shrank

and dried as the climate warmed. However, many swamps and lakes that

existed when the pioneers settled in Indiana were created during the Ice

Age and some remain viable aquatic habitats up to the present time.

The Alton, or Magnet, site in Perry

County is important for our understanding of

Paleoindian occupations of the Hoosier National Forest. It is a large

and important base camp where many Paleoindian projectile points,

including Clovis points, have been found. This site represents a special

location where Clovis and other groups lived, manufacturing new spear

points and other tools, and probably making homes (Figure 25). From this

site, the people geared-up many times for major hunts in the hill

country and valleys of southern Indiana and returned again to eat, rest,

make and repair clothing and shelters, and make new tools.

|

|

Figure 25 (above and right): Clovis projectile point and blade tools

made from Wyandotte chert. The blade tools are pressure retouched on the

margins to form edges for cutting meat and scraping hides. These and

many other Paleoindian tools have been found on the surface of the Alton

(Magnet) site in Perry County, IN (Courtesy of Donald Champion).

|

The Potts Creek Rockshelter produced a broken Clovis

point (Figure 26). The projectile point was found in a small pile of

artifacts left on the floor of the shelter by looters after they had

severely churned the shallow deposits for prehistoric artifacts. Sadly,

such looting behavior has ruined some of the better archaeological sites

in the United States and, unless stopped, the last

vestiges of data on America's

first peoples will be lost forever (Figure 27). There are reports from

local persons familiar with the Hoosier National Forest that other

Paleoindian projectile points and tools have been collected from other

rockshelters as well. Such circumstantial evidence suggests that

rockshelters may have been used regularly in south-central Indiana

beginning with Paleoindian occupations in the region as temporary homes

away from larger base camps.

|

|

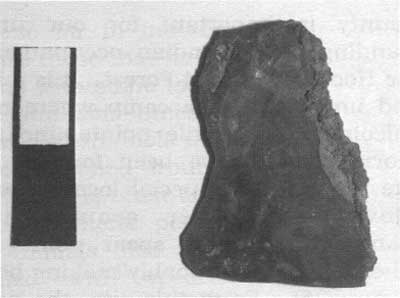

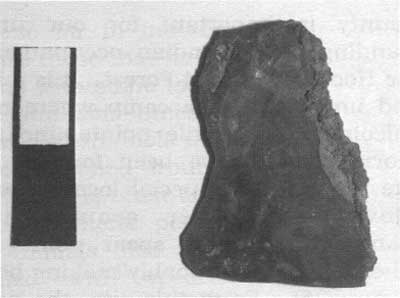

Figure 26: Clovis point base found in looter's

spoil pile at Potts Creek Rockshelter. The specimen has an

encrustation of calcium carbonate on the break which is common on

ancient tools long buried in damp, chemically rich soil. The point is

also damaged from the heat of a fire. Perhaps long ago while a Clovis

hunter stayed at the shelter for protection from the weather to eat,

relax and repair weapons, he cut the sinew binding and discarded the

broken base in a campfire and then rearmed a spear with a freshly made

Clovis point before leaving to resume hunting. (2 cm scale)

|

|

|

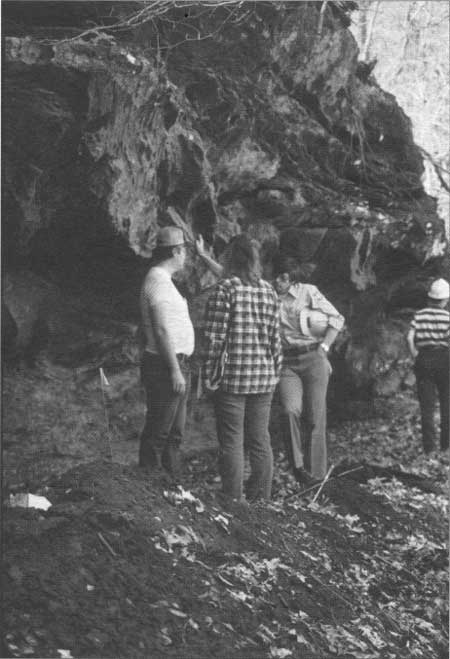

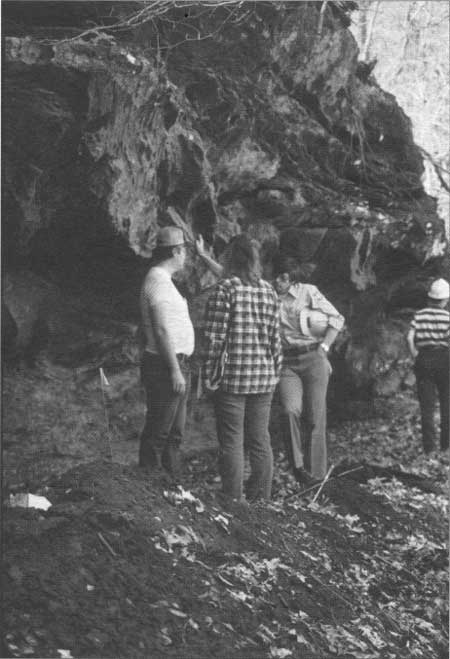

Figure 27: Archaeologists at Potts Creek Rockshelter discussing the

looting damage and how to proceed in the investigation and

assessment.

|

The archaeological deposits at Rockhouse Hollow

Shelter in Perry County are at least eight feet deep and excavations

there in 1961 by James H. Kellar, with a permit from the Forest Service,

proved that the occupations began during or before the Early Archaic

period (Figure 28). Rocks that had fallen from the roof of the sandstone

alcove and yellow sandy soils were encountered in the

deepest areas excavated at the shelter, but solid bedrock was not

recorded in any of the excavation units. Thus, there remains some

potential for finding a buried Paleoindian or older occupation within

this and other rockshelters. While no bones of Ice Age animals or

other remains were found to indicate the age of the early deposits, the

results of the excavations prove that the rockshelter was open for

occupation and accumulating sediments during this time. It appears when

people realized the attractiveness of a particular shelter, they

returned for thousands of years thereafter (Figure 29). There is also

the distinct possibility that the remains of

some very ancient rockshelters are

now buried and no longer visible on the surface. This happens as a

natural evolution of hillsides and rock exposures as soil erosion takes

place along with the collapse of rock overhangs. In the early 19th

century, farming and clear-cut logging operations also caused severe

erosion of the top soil that added to the deposits along steep slopes

(Figure 30). Ancient buried rockshelters could exist anywhere along the

old ravines of the Hoosier National Forest. While they would be

difficult to detect, some could hold the key to the first peopling of

Indiana during the Ice Age that may be much more ancient than we

presently know (Figures 31-32).

|

|

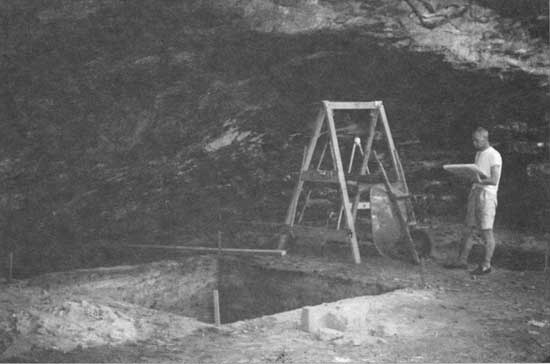

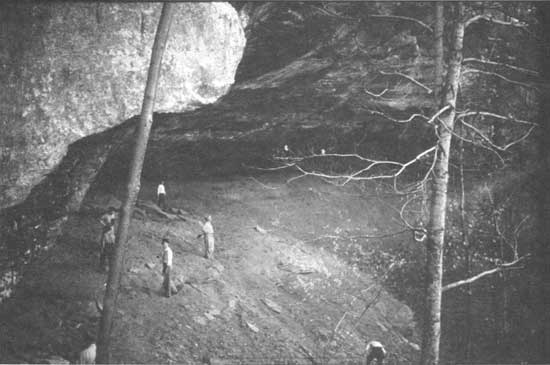

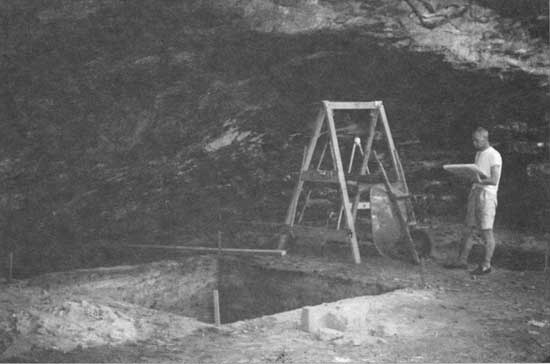

Figure 28: Record keeping during 1961 excavations within Rockhouse Hollow

Shelter, Perry County, IN. The test excavations by James H. Kellar demonstrated the

deposits were over eight feet deep at the rear of the overhang and the

site contained evidence of human occupations spanning 10,000 years.

|

|

|

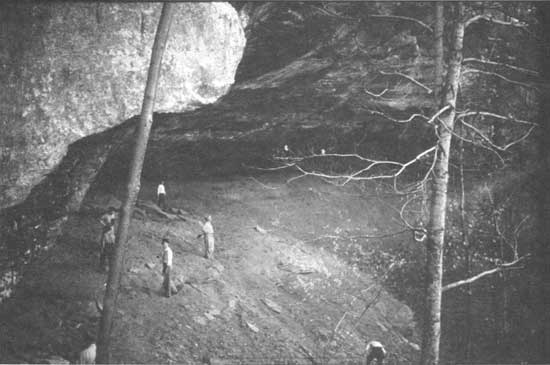

Figure 29: An early trip to Ash Cave, Perry County, IN. Note the

sandstone rocks (break down) on the floor and slope of the shelter that

have fallen from the roof in the course of natural

weathering over thousands of years. The decomposition

of the rock ledge is largely due to the variation in weather during the

different seasons of the year. Alternating wet and dry and freeze and

thaw cycles causes the rock to break off in sheets and blocks following

naturally weak cracks and lenses within the rock.

|

|

|

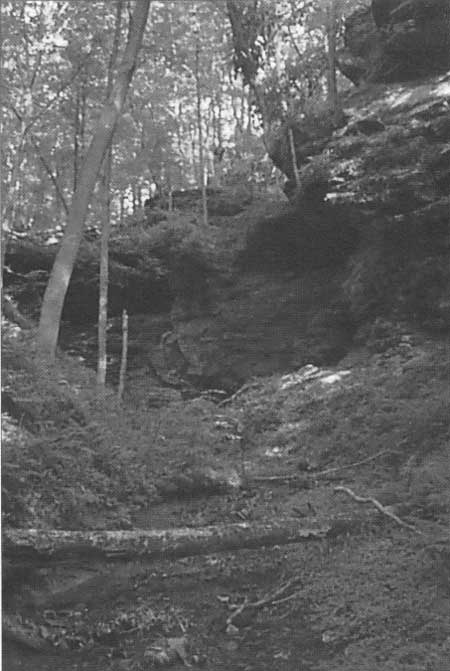

Figure 30: A rockshelter investigated during the 1999 Hoosier National

Forest archaeological survey. Note the overhang and slope mixed with

soil and rock, fallen from the ceiling and also washed in from the sides

of the overhang.

|

|

|

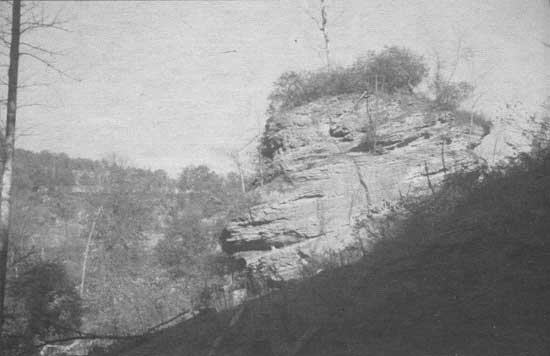

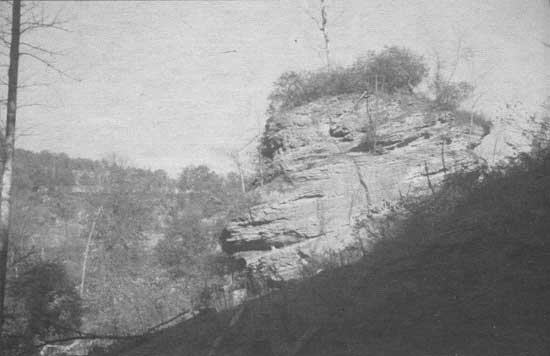

Figure 31: A hill in Perry County showing a large piece of sandstone

bedrock on the slope. Untold numbers of prehistoric people may have

happened by this place when an ancient rockshelter was still open for

habitation. Today, all such remains are probably buried beneath

weathering sandstone and soil on the hillside.

|

|

|

Figure 32: Prehistoric mortars for processing nuts and other foods on

the floor of Peter Cave in Perry County, IN. These are often referred to

as "bedrock mortars" but they are often large blocks of sandstone fallen

from the roofs of caves and rockshelters that may preserve the remains

of ancient campsites beneath them.

|

9/hoosier/prehistory/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008 |

|