|

Looking at Prehistory: Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 12,000 B.C. to 1650 |

|

Looking at Prehistory:

Early Archaic Period 8,000 to 6,000 B.C.

The Early Archaic period is a time when hardwood forests and prairies were established in Indiana in response to the warming climate after the Ice Age. Whitetail deer became a primary source of meat for Archaic peoples, along with black bear, elk and many smaller animals that live in Indiana today. In Indiana black bear and elk were finally hunted to extinction by around 1850. Collections housed at the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology contain a black bear skull reportedly found near Hazelton, Indiana that exhibits a round hole in the skull, indicating a musket or rifle was used to kill the animal. Bison were numerous and heavily exploited on the central Plains during the Paleoindian and Early Archaic periods, but not in the eastern United States.

Early Archaic people, much like the Paleoindian people frequently changed the locations of their hunting and collecting camps to take advantage of hunting opportunities. Their camps were most often small and only used for a short time. A camp fire or two with some rocks and debris from making tools along with a few broken and worn-out tools is all that many sites contain. While there is no archaeological evidence of structures during the Early Archaic and the earlier Paleoindian period, their homes were probably made with poles and covered with hide, grass, or bark depending on the location of the camp and the available building materials. These remains are so old and scarce that little has survived to help us understand these people and their lives. Early Archaic peoples are no doubt descended from earlier Paleoindian people, but the genetic relationships can only be determined generally because early human remains that can be used for genetic analyses are scarce and widely scattered. Based on the numerous types of tools and the wide geographic dispersal of these tools, we can be sure that there were numerous individual groups of people, more or less related, but nonetheless distinct in their own right. This same statement applies to what we also know for many later archaeological periods.

Like Clovis and earlier Paleoindian peoples, Early Archaic people frequently revisited chert quarries where large pieces of high quality chert could be used to make projectile points and butchering tools. Early Archaic projectile points are some of the most common and readily recognized tools in prehistory because they are larger than average, were made in large numbers, and were left at thousands of hunting camps spread across the landscape in all areas of Indiana.

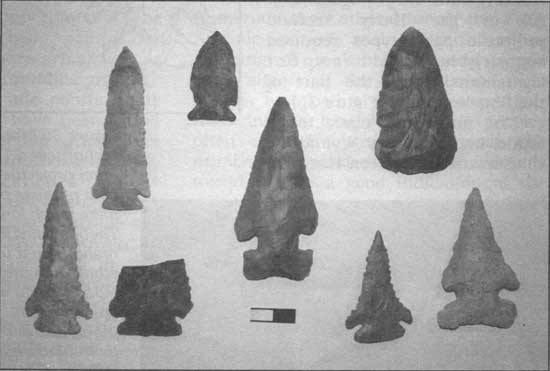

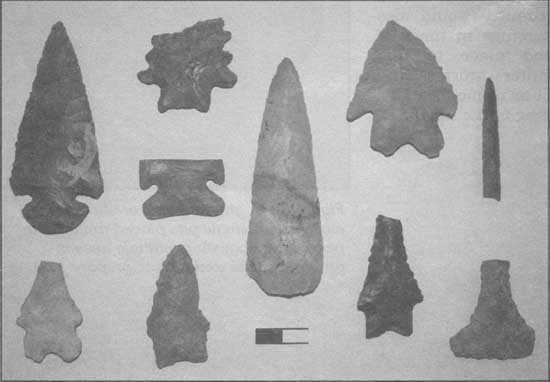

The most common Early Archaic projectile points belong to the Thebes and Kirk Corner Notched clusters, but there are several other major clusters of point types that are known for this period (Figure 33). There are many types and varieties that represent different Indian groups that may have spoken different languages and dialects. This is because the tools themselves were manufactured and re-sharpened using unique manufacturing strategies and techniques that were difficult to master and had to be taught to novices who maintained the different manufacturing traditions for generations without significant changes. Thus, it appears even at this early time, there were many Indian cultures that over time only became more numerous and complex.

|

| Figure 33: Early Archaic Thebes and Kirk Corner Notched Cluster projectile points. The Kirk points are from archaeological investigations at Swans Landing and Rockhouse Hollow Shelter. The thin, unnotched piece (preform) on the right was made by Kirk knappers. Preforms were sometimes kept for use as hand-held knives or stored with others for later use, when a new spear point or knife was needed to tie securely (haft) to a spear or handle with sinew. Perhaps the preform was lost or forgotten before the owner had a chance to pressure flake the corner notches. |

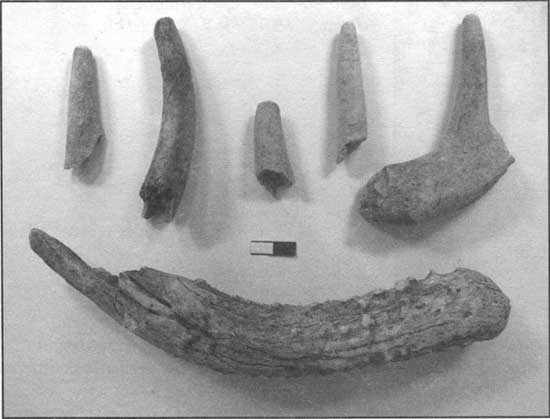

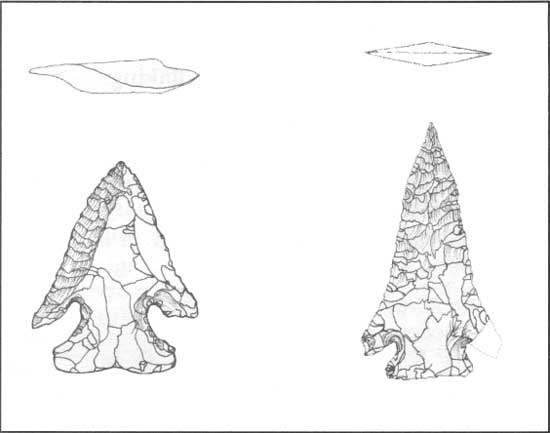

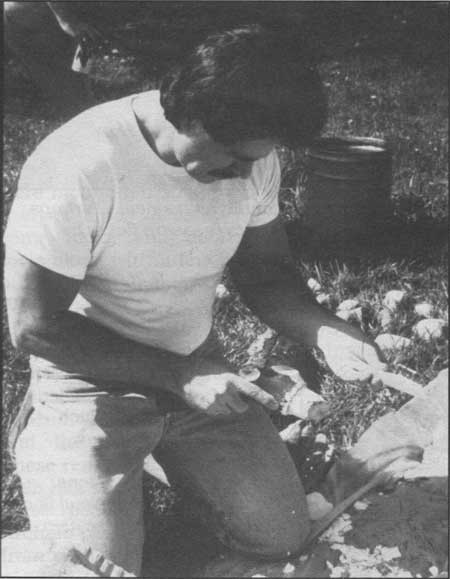

The manufacturing process begins with controlled percussion on blanks and large flakes struck from cores. Thebes cluster points were made mainly with percussion, but Kirk points were made mainly with pressure flaking, which was also used in resharpening cutting edges when the tools became dull from use (Figure 34). Resharpening of Thebes cluster projectile points, on the other hand, is marked by alternate beveling using pressure flaking on opposite sides of the cutting edge (unifacial), presumably to remove less material while achieving a sharp cutting edge--in order to keep the tools in use as long as possible. Kirk cluster projectile points were nearly always finished with pressure flaking on both faces (bifacial) and this probably created more waste, and required more trips to quarries or frequent trading to obtain new tools. Notching on Kirk points involved pressure flaking to achieve a narrow notch, whereas Thebes cluster points probably required the use of indirect percussion with a punch along with pressure to create deeper notches in several designs on refined bifaces much thicker than Kirk (Figure 35). All of the Early Archaic projectile point types required strength and expert craftsmanship on the part of the flint-knappers (Figure 36).

|

| Figure 34: Archaic and Woodland period flint knapping tools made from deer antler. The tips of the antler tines (above) are worn back from repeated heavy use in pressure flaking. Such tools were also used as punches struck with a hammer of antler or stone. The antler section (below) is a baton, or billet, for use as a hammer and percussion flaking. The butt-end is rounded and battered from repeated use in percussion to thin bifaces in the process of making stone tools. |

|

| Figure 35 (above): Heavily used and resharpened Thebes and Kirk (Pine Tree) projectile points. When new, both of these points had blades that were much longer and wider. The Thebes point (left) has been resharpened unifacially (one blade edge) with pressure flaking on the left side creating a bevel as shown in the cross section. The Kirk cluster point (right) has been resharpened bifacially (both blade edges) with pressure flaking maintaining an edge in the middle of the cross section. The cross sections show what the specimens look like when oriented vertically and viewed from above (Modified from Justice 1987: Figs. 12j, 14k). |

|

| Figure 36: The author demonstrating the use of an elk antler billet for bifacial percussion thinning to make a projectile point during "Discovering Archaeology," Indiana University, 1990's. Photo courtesy of Ms. Jodi Pope-Pfingston. |

The finest raw chert to be found in Indiana is Wyandotte that occurs in western Harrison and eastern Crawford counties. This chert was perhaps used more frequently than any other in Indiana from Paleoindian times onward. Excavations at sites such as Swans Landing and Caesars, located on the Ohio River, have produced thousands of fine examples of Kirk Corner Notched cluster projectile points made from this chert. The sites show the hunters were expert flint-knappers who apparently created a surplus at quarries, perhaps to be cached for use at base camps for hunting surplus and extra armament, as well as for trade to surrounding groups.

Early Archaic projectile points made from Wyandotte chert have been found on all landscapes, including rockshelters in the hill country of southern Indiana. Excavations at Rockhouse Hollow Shelter in Perry County suggest a limited use of the shelter during the Early Archaic (Figure 37). However, no evidence of houses was found in this rockshelter or any other archaeological sites. No human burials that date to this time have been found in the Hoosier National Forest, although a few Early Archaic burial sites are known in southern Indiana that included the placement of chipped stone tools and red ocher (e.g. iron oxide) with the deceased. Most likely, the people believed in an afterlife and so the deceased person would need their personal toolkit. Red ocher was apparently highly prized from Paleoindian times onward. It could be ground into a powder, mixed with grease or water to make paint or dusted over a dead body to give back the flush of life.

|

| Figure 37: A range of Early Archaic period projectile points and tools. These are from Rockhouse Hollow Shelter and surface investigations in the hill country of southern Indiana. |

Kirk peoples may have been more numerous than others during the Early Archaic period with larger families camping at rockshelters and various open sites. If the people who made Thebes type points regularly kept their tools in use longer and Kirk peoples often created a surplus of tools, the number of expended and discarded tools would not be a good indication of the number of people and the amount of time spent at various hunting and base camps. Another important consideration is that the floodplains of the major waterways hide many early human occupations because of yearly cycles of flooding and the resulting deposits of water transported silts. In addition, hillside erosion into valleys has covered many early sites, including rockshelters. Even today, sites in these situations remain buried and are known only from bank erosion and deep exploratory trenching.

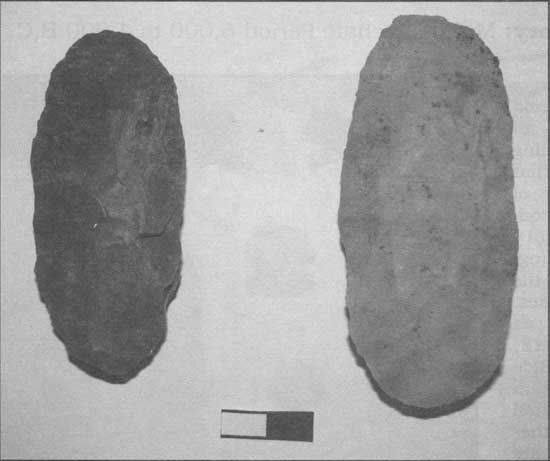

We know Early Archaic peoples brought deer and various collected nuts to rockshelters and open sites for consumption and made limited use of hammerstones, stone slabs and pitted stones for shelling and grinding nuts and seeds (Figure 38-39). Another potential use for stone hammers and slabs was processing dried deer meat and berries to store for use in late winter when deer are dispersed, the fall store of nuts is about gone, and fresh plant foods of the spring and summer are not yet available. Another tool type used in the Early Archaic is the chipped stone adze that appears to have been used in wood cutting thousands of years before the ground stone grooved axe was invented (Figure 40). While perhaps remaining only for a few weeks at a time while hunting within the hollows and ravines of the Hoosier National Forest, Early Archaic people apparently made regular seasonal use of the hill country while hunting and collecting many miles away during other times of the year. The narrow and rugged hollows and ravines of the hill country would also have been places of refuge in times of trouble and a good place to find protection from winter storms and summer heat, as well as prime locations for camps while hunting in the uplands.

|

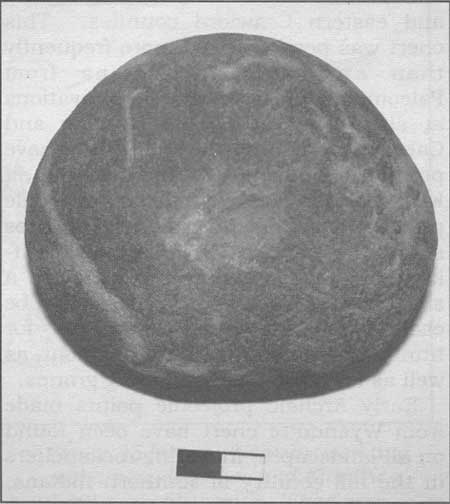

| Figure 38: A pitted stone for cracking nuts from the Early Archaic period occupations at the Swans Landing site. |

|

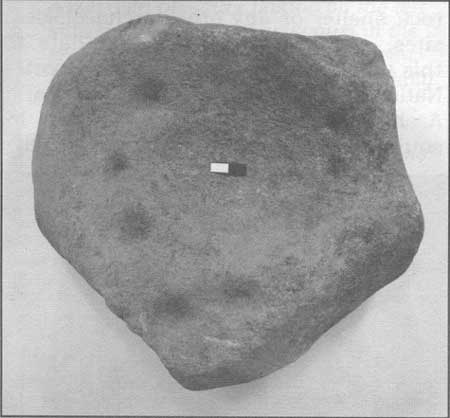

| Figure 39: A grinding slab or shallow mortar with single pits placed around the perimeter suggesting multiple uses in grinding seeds and nuts to prepare food. |

|

| Figure 40: Chipped adzes are the first in a long line of wood cutting tools and appear first during the Early Archaic period. These are from Swans Landing (left) and Rockhouse Hollow Shelter. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

9/hoosier/prehistory/sec2.htm Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008 |