Looking at Prehistory:

Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 12,000 B.C. to 1650

|

|

Looking at Prehistory:

Middle Woodland Period 200 B.C. to A.D. 500

The Middle Woodland period marks a high point in

trade and ceremonialism that is unparalleled by anything before or after

this time period. Hopewell, named for a site in central Ohio, is a

ceremonial and cultural phenomenon that spread throughout the eastern

Woodlands early in the period. People began constructing complex burial

mounds that included the building of log tombs, earthworks, and the use

of goods made from exotic raw materials within burial tombs representing

the wealth and status of elite persons. Average community members may

never have seen or handled some of the exotic trade goods destined for

use in the afterlife. Hopewell ceremonialism and long distance exchange

took place between Middle Woodland communities spread over a wide

territory.

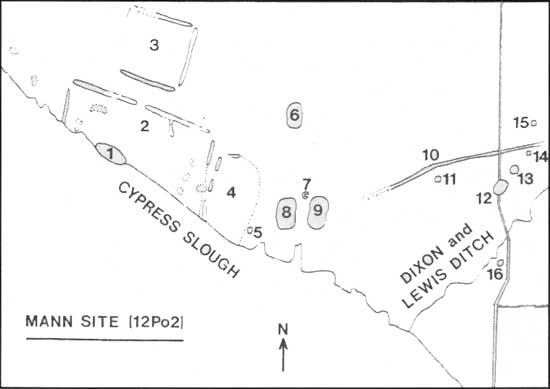

Middle Woodland period camps and small villages are

located over all of southwestern Indiana. They are probably more

numerous in the hill country of southern Indiana and the Hoosier

National Forest area than the

current data shows, but rockshelters were heavily

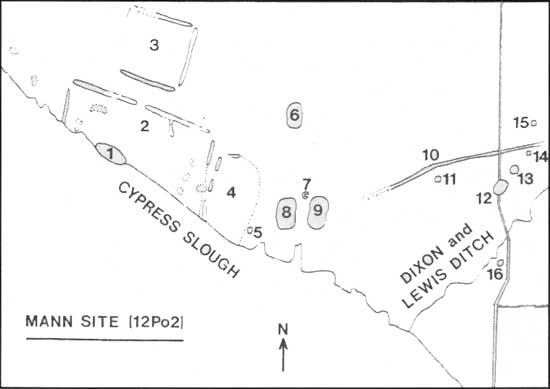

used early in the period. The Mann site, along with the GE or Mount

Vernon Mound, which is named for a location near that town in

southwestern Indiana, are the largest and most complex Hopewell sites

known in the region. These sites became important ceremonial centers

that probably attracted people of different cultural and social

affiliations, along with a large variety of exotic goods traded from

sources far outside the region (Figure 67). Many other mound sites of

Middle Woodland affiliation are probably also located in southwestern

Indiana but, they have not yet been recorded (Figure 68). There are some

reports of possible Middle Woodland mounds from the region immediately

adjacent to the Hoosier National Forest in the Tell City and Harrison

County areas along the Ohio River, although very little is documented

about them.

|

|

Figure 67: A map of the Mann site, Posey County, IN showing the

locations of large mounds and earthworks (modified from Kellar

1979:Fig. 14.1).

|

|

|

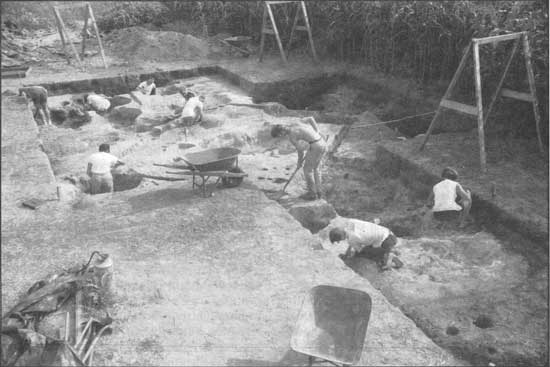

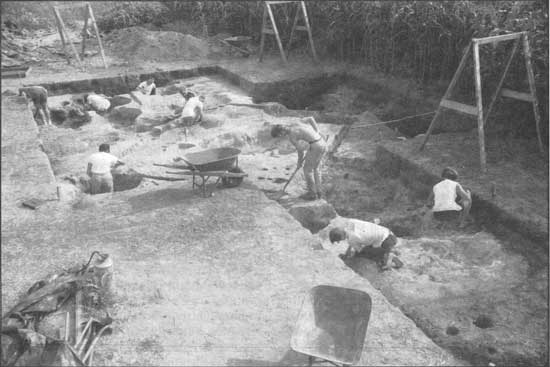

Figure 68: Ongoing excavations at Mann site in 1967 by Indiana

University to carefully document the prehistoric pits and other

features, and also the locations and associations of

artifacts being recovered.

|

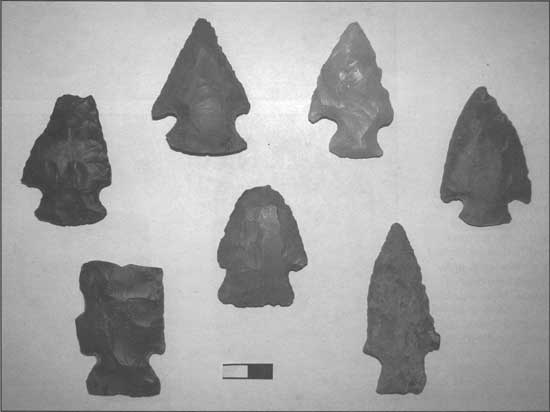

The Crab Orchard tradition and the Mann phase

represent the most notable Middle Woodland cultures in the region.

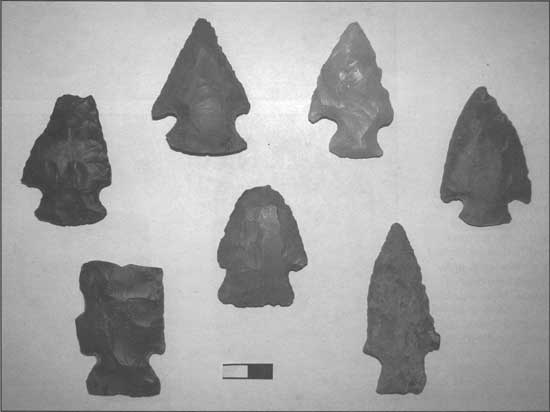

Projectile points of the period include those of the

Saratoga and Snyders clusters that belong to the Crab Orchard tradition

and the Lowe and Copena clusters that belong to the later Mann phase

(Figures 69-70). Many styles of ceramic vessels were developed during

this period and the incorporation of knives or blades struck from

prepared cores is an important addition to the tool kit. Flake blades

were probably used for carving wood and fine incising on bone and wooden

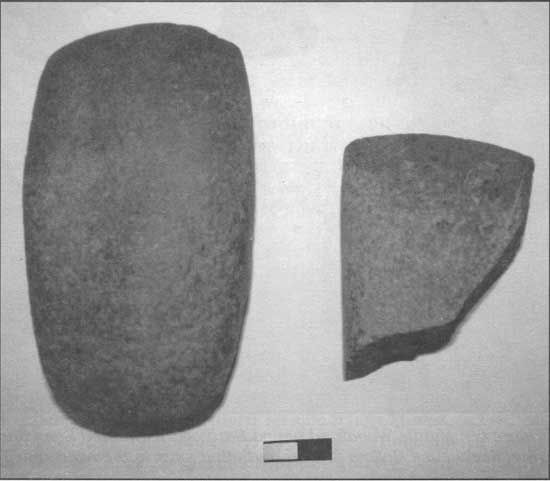

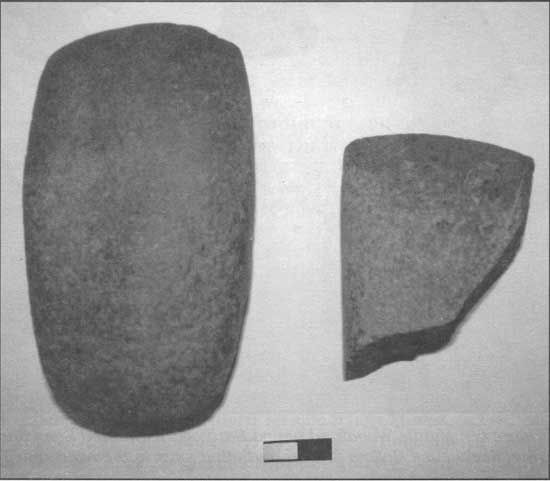

articles of all descriptions. Other tools characteristic of the Middle

Woodland period include celts, which are basically ungrooved axes for

cutting and hewing wood (Figure 71), various types of scrapers made from

large flakes, mortars and pestles and other grinding stones.

|

|

Figure 69: Middle Woodland period Saratoga Expanded Stem and Snyders

projectile points from Rockhouse Hollow Shelter and other sites in the

hill country.

|

|

|

Figure 70: Middle Woodland period Lowe Flared Base

and Copena Triangular projectile points from Rockhouse Hollow Shelter

and other sites in the Hoosier National Forest.

|

|

|

Figure 71: Celts or ungrooved axes. After several

thousand years, the ax was modified to be hafted to a wooden handle

without making a groove. Presumably the ax-head was fitted to match

a hole cut through the handle.

|

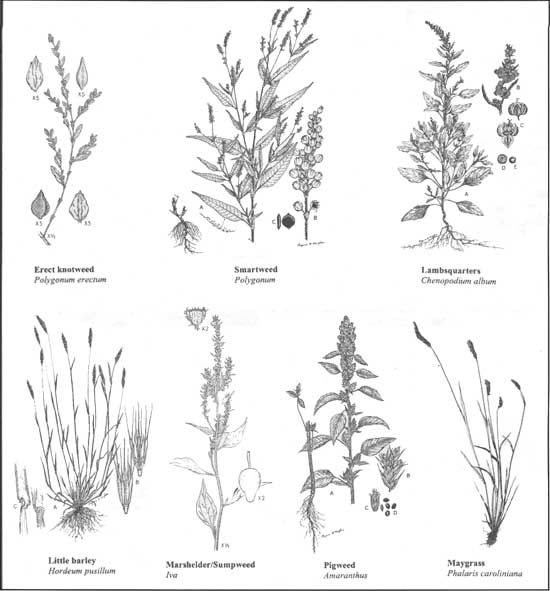

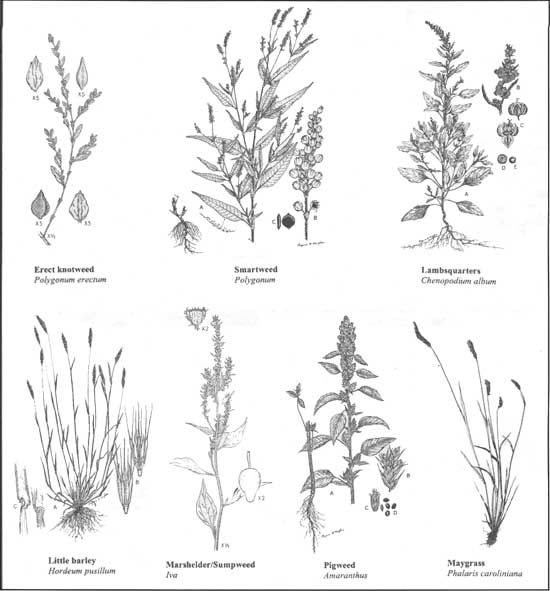

While agriculture within large prepared fields does not take place until the Late

Woodland period several hundred years later, Middle Woodland peoples

were cultivating a number of seed producing plants including sunflowers,

lambsquarters or goosefoot, maygrass, erect knotweed, little barley and

probably a large variety of other plants (see Figure 72). Most of these

plants have oily and starchy seeds that could be ground into meal with

mortars and pestles to make breads and cakes, or as an additive in other

food preparations. Corn makes its first appearance during this time, but

it was not grown in any large quantities. Corn, along with the knowledge

of how to use it, is ultimately derived from northern Mexico where it

was passed on from village to village with ever increasing popularity

until finally reaching the Ohio Valley.

|

|

Figure 72: A few wild food plants used in prehistory. There are many

species and varieties of food and medicinal plants used by Native

Americans today and long ago. Some of the plants identified at

archaeological sites apparently went extinct before the present day such

as a species of marshelder (Iva annu) that was domesticated. The oily

seeds of this plant appear in archaeological sites during the Middle

Archaic period, and the plant was regularly harvested for its

nutritional value along with many others for several thousand years

thereafter. The illustrations shown here are modified from several

sources (USDA 1971: Figs. 33, 60, 64, 71 with drawings by Regina O.

Hughes; Gleason 1952: Vol. II, p. 75, Vol. III, p. 373; Cowan 1978: Fig.

2).

|

The Crab Orchard tradition is named for Crab Orchard

Lake in southern Illinois. This tradition develops within the lower Ohio

Valley and extends to include all of southern Illinois and northern

Kentucky, up the Ohio River to near the Falls of the Ohio area in Clark

County and a short distance up the Wabash River. The first pottery

attributed to the Crab Orchard tradition is a coarse, rock-tempered

pottery known as Sugar Hill Cord-marked which then gives way to

clay-tempered pottery which is the primary ceramic of the Crab Orchard

tradition. Clay temper is fired clay that was crushed and may include

fragments of broken pots that were crushed and added to fresh clay to

form new ceramic vessels. Later in the Middle Woodland

period many types of rock, including crushed quartz, feldspar,

limestone, sandstone, as well as sand and clay, were used as tempering

agents.

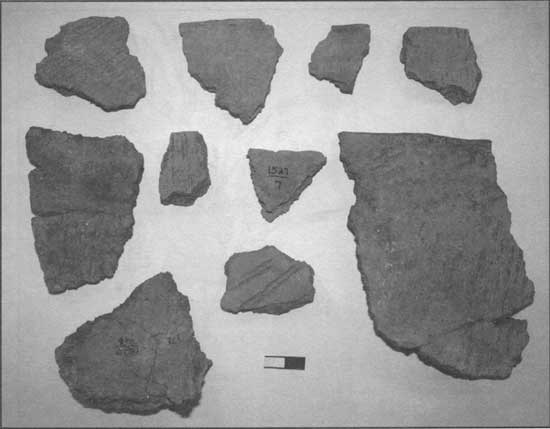

The Crab Orchard people lived in the larger

rockshelters of the Hoosier National Forest and left substantial

evidence of their presence, including quantities of pot-sherds (e.g.

fragments of broken pots) from the large cooking and storage vessels

they made and used (Figures 73-74). Rockshelters were probably used for

temporary shelter while hunting and collecting in the rugged terrain,

although the shelters may have been visited regularly throughout the

year and could have been used for several months

consecutively as hunters and their families moved back and forth into

the hill country from base camps within the floodplains and on the

terraces of the Ohio River.

|

|

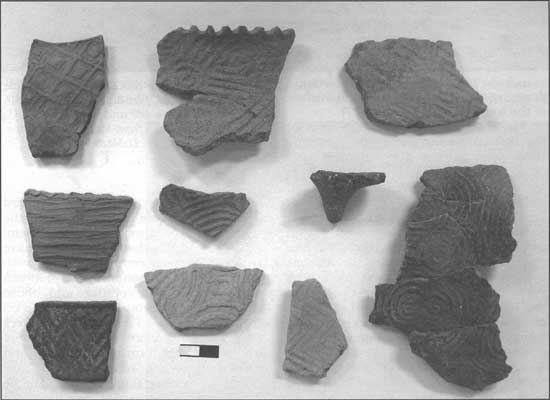

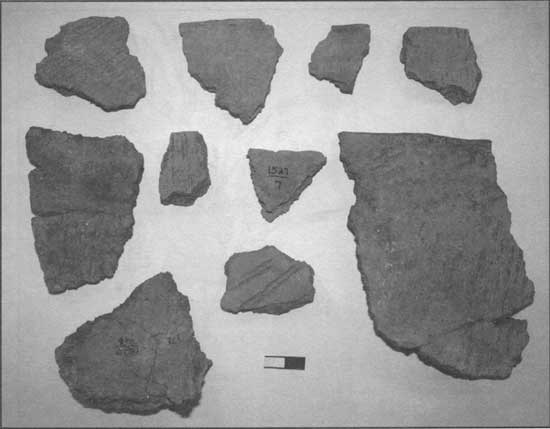

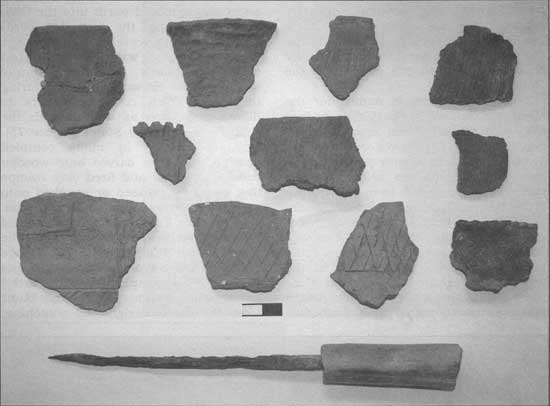

Figure 73: Pottery belonging to the Crab Orchard tradition from

Rockhouse Hollow Shelter.

|

|

|

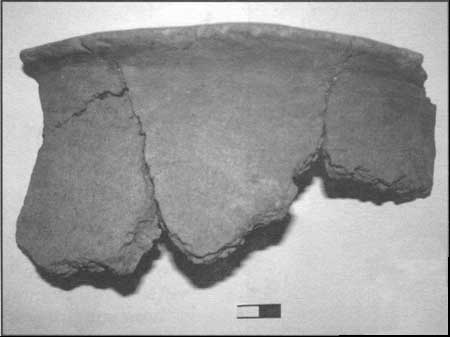

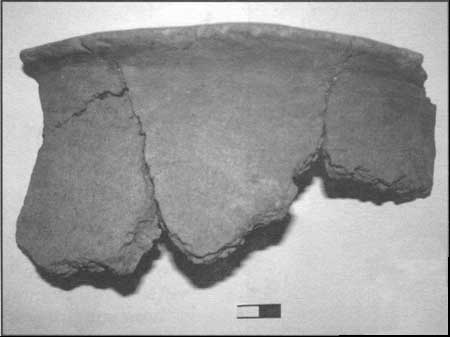

Figure 74: Large rim of a pottery vessel belonging to the Crab Orchard

tradition, from Rockhouse Hollow Shelter.

|

The Mann phase is named for the Mann site located in

Posey County that may have initially been established by people of the

Crab Orchard tradition. These people were already present in the valley

a few centuries before, yet the ceramics at Mann site have many types of

temper and designs and some are definitely southern in derivation. For

example, ceramic stamping technology and also the Lowe and Copena

projectile point technologies appear first in the southeastern United

States and their presence in Indiana probably means some groups of

people from Tennessee and Georgia moved north into the Ohio Valley. Among

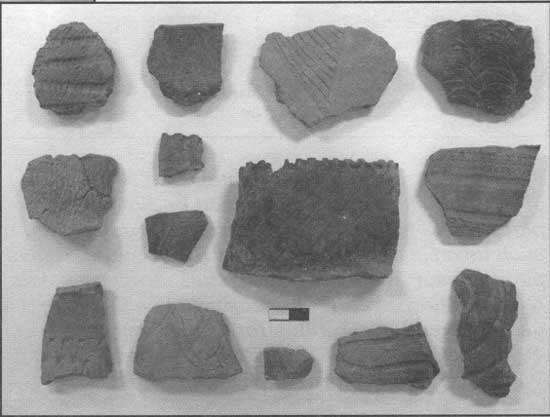

the everyday cord-marked cooking vessels, the Mann site has ceramics

with complicated stamping, check stamping, simple stamping and elaborate

incising during this time which connects potters to Illinois and Ohio as

well as with the southeastern United States (Figure 75). Stamping comes

in many complex designs that were carved onto wooden paddles or dried

and fired clay stamps that could be pressed or spanked onto the sides of

clay vessels still wet from manufacture. The use of stamps enabled the

manufacture of pottery with the same precise design (Figure 76). There

are many other types of pottery designs that were accomplished with

artful hands using various sharp and blunt tools to create designs by

punching, dragging or cutting (incising) the surface of the

wet clay vessel (Figure 77).

|

|

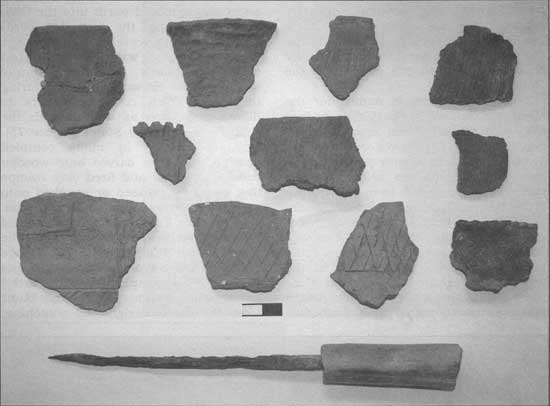

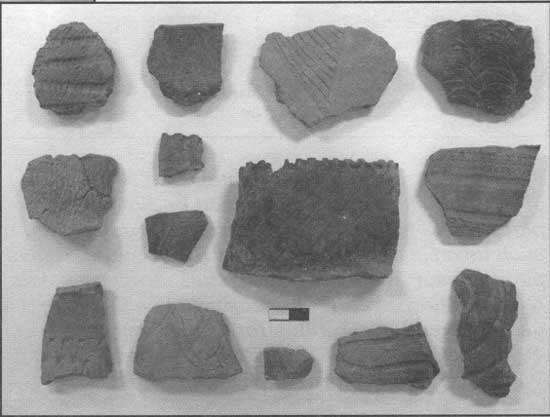

Figure 75: Hopewell and other

Middle Woodland period decorated pottery from the Mann site and

Rockhouse Hollow Shelter.

|

|

|

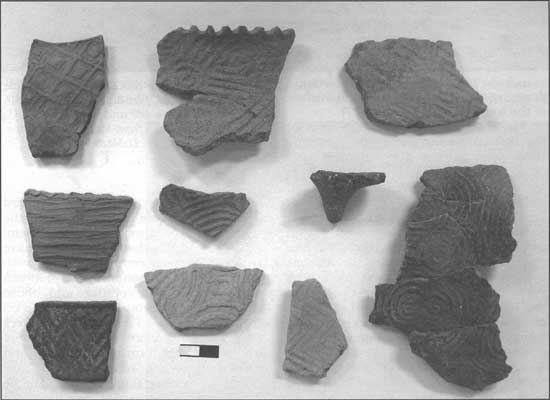

Figure 76: Complicated-stamped and simple-stamped ceramics from the Mann

site.

|

|

|

Figure 77: A copper awl with a bone handle from the Cato site,

fine-line incised ceramics from the Mann site and later Middle Woodland

ceramics from Mann, Rockhouse Hollow, and Allison-LaMotte sites to the

north.

|

The Allison-LaMotte phase defined for the Wabash

Valley north into the Terre Haute area dates to the same time and could

be a manifestation of the Mann phase or visa versa. Most of the cultural

traits are duplicated, except Allison-LaMotte lacks burial mounds,

earthworks and evidence of high ceremonialism. Perhaps the Mann site was

also a special center for Allison-LaMotte peoples who lived along the

Wabash. Most of the domestic pottery of the Mann phase and

Allison-LaMotte is dominated by thin, cord-marked vessels with a variety

of tempers added to the fresh clay.

Rockshelter sites in the Hoosier National Forest may

not have been used as intensively during the Mann phase as

they were by the earlier Crab Orchard people, since

there is much less in the way of pot-sherds we can relate to them. Yet,

it is possible that families may have typically carried ceramic vessels

with them on their seasonal rounds between sites in the hill country and

those scattered over surrounding areas and on the Ohio River. Perhaps

the shelters were occupied more often by hunters who left mostly hunting

equipment and carried meat and hides back to base camps where their

families lived. Middle Woodland trading parties may have also

occupied the rockshelters on their way to and from

major Hopewell centers, transporting a variety of exotic and domestic

goods. In addition, at least some of the people using the hill country

may have taken part in ceremonies at Mann site or the GE Mound or, at

least, obtained some of their tools and other artifacts through

interaction with people from those sites. The GE Mound was unfortunately

severely impacted by looting and we may never know the full importance

of the site. Hopefully other Hopewell ceremonial sites will be reported

and documented before they are destroyed by construction or looting.

The Mann site and GE Mound were extremely important

ceremonial and trade centers that participated in the exchange of

grizzly bear teeth and obsidian from the Rocky Mountains along with

copper, mica, marine shell, pearls, and exotic cherts from locations all

over the eastern United States and the Plains (Figure 78). Gifted

craftsmen produced large spear points of obsidian obtained near

Yellowstone National Park, quartz crystal obtained from special quarries

and caves, and Knife River flint from the Dakotas. Mica, probably obtained

in the Smokey Mountains, was often used to make elaborate cut-outs in

the shape of human hands and birds. The Mann site is well-known for the

large numbers of finely made human figurines of fired clay that have

been found there (Figure 79). Each figurine depicts unique and unusual

hair styles used during the Middle Woodland period and many other

details including clothing, special postures and facial features. The

numbers and kinds of Hopewell ceremonial goods is incredible and

testifies to the sophistication of the times and the extent to which

people would travel overland and by canoe to obtain special goods for

elite persons and ceremonies.

|

|

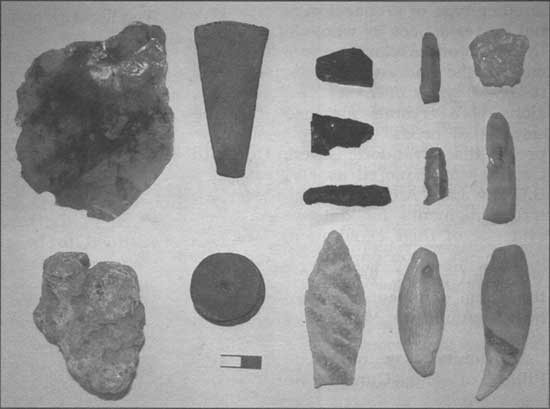

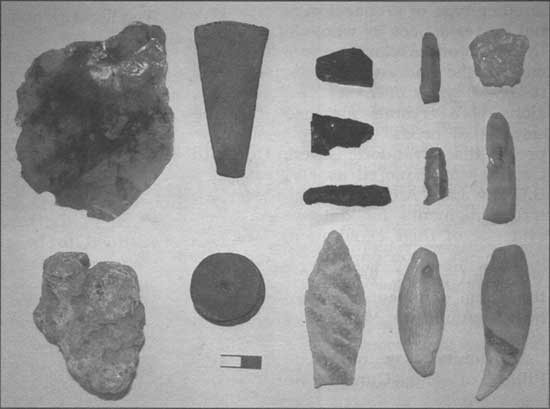

Figure 78: Hopewell artifacts made from exotic raw

materials including mica, copper, galena (lead crystal), obsidian,

quartz, sugar quartz and flint ridge flint. Most of the items are from

the Mann site.

|

|

|

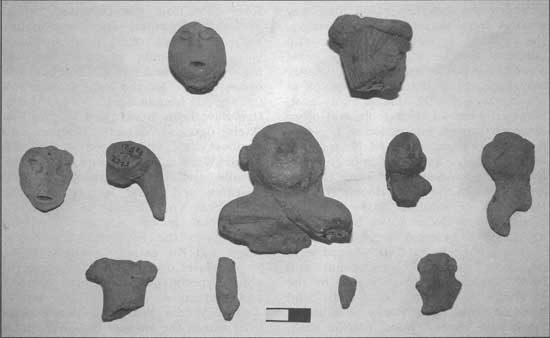

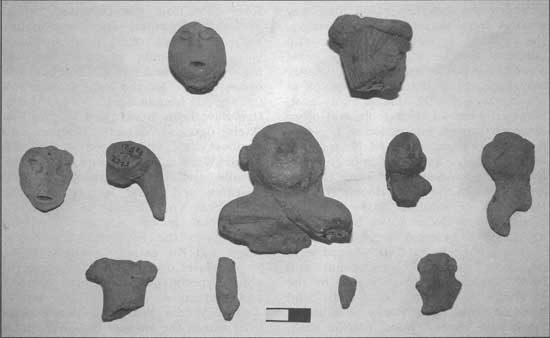

Figure 79: Hopewell human figurine fragments of fired clay. The two

small appendages at the bottom were recovered during the 1961

excavations at Rockhouse Hollow Shelter.

|

The Middle Woodland people who lived within the

Hoosier National Forest left flakes of quartz crystal, fragments of

mica, blades of Flint Ridge chert from Ohio and some human figurine

fragments. Such finds are highly significant because these were

apparently not materials that were used on a daily basis by common

people of the time. The presence of such

materials at sites in the hill country testifies that these people were

connected to the vast Hopewell trade in exotic goods that took place

throughout much of the eastern United States.

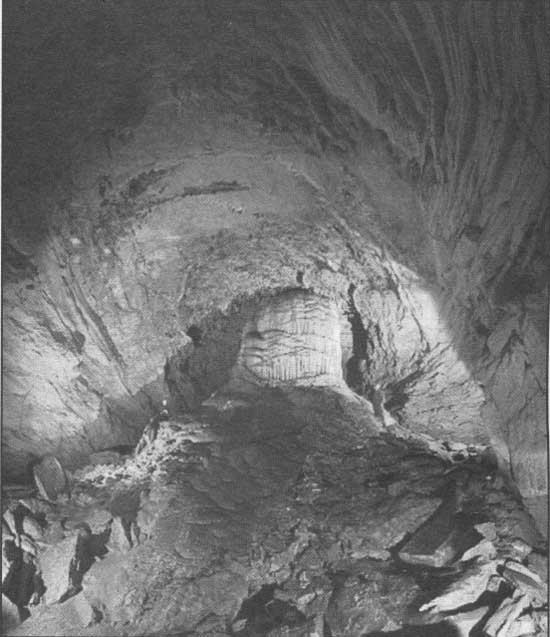

Underground caves constitute another type of

archaeological site used not for residences by whole families, but by

prehistoric explorers and miners who entered the underworld to extract

many unusual types of rocks and minerals, along with crystals for

medicinal and ceremonial needs. Archaeologists have proven that

Wyandotte Cave in Crawford County was explored as early as 2000 B.C. by

Late Archaic peoples who left torch fragments for dating and other

evidence of their explorations long ago (Figure 80). Later on, during

the Middle Woodland period, Wyandotte Cave was the scene of repeated

explorations and heavy mining (see Munson and Munson 1990).

|

|

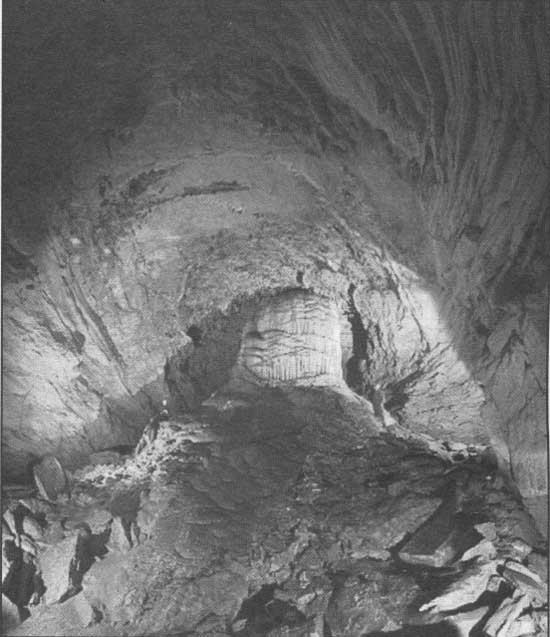

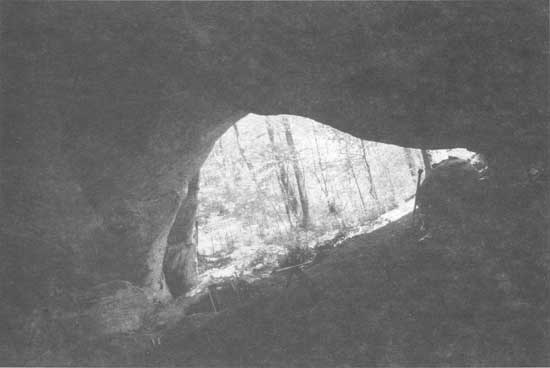

Figure 80: The "Pillar of the Constitution" deep

within Wyandotte Cave (Courtesy of Gary Berdeaux, photographer, Carol

Groves and Cave Country Adventures, 400 E. State Road 64,

Marengo, IN).

|

Aragonite was quarried from the Pillar of the

Constitution within Wyandotte Cave during the Middle Woodland period.

Aragonite is a semi-translucent, banded flowstone composed of calcium

carbonate that sometimes is the rock that forms stalagmites and

stalactites within caves. The remains of stone hammers and antler pry

bars have been found, along with fragments of aragonite, charcoal, and

ash that were buried within quarry debris around the base of the Pillar

of the Constitution. Much of the aragonite was apparently destined to be

carved into ceremonial platform pipes and gorgets (e.g. drilled

decorative items often shaped like a reel) and traded to far away

Hopewell ceremonial centers in Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, Iowa, and

Tennessee. A fragment of a carved aragonite pipe was recovered in

scientific excavations of Arrowhead Arch in Crawford County

and dated to about A.D. 155. There are also fragments of this material used

for ceremonial artifacts in the collections from the Mann site (Figures

81-82). Carbon-14 analysis suggests that aragonite was quarried in

Wyandotte Cave during the first centuries of the Christian Era. Such

material and the artwork created from it was probably distributed across

the Hoosier National Forest en-route to Hopewell ceremonial centers.

Many other important substances could only have been obtained by brave

spelunkers within the dark recesses of Wyandotte and other caves in

prehistory. Some of these are noteworthy and include epsom salts

(epsomite), gypsum (also good for carving objects), saltpeter and

nitrates, the latter of which were important in early historic time for

making gun powder.

|

|

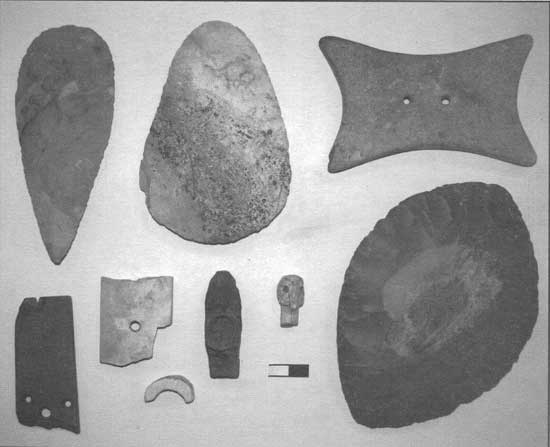

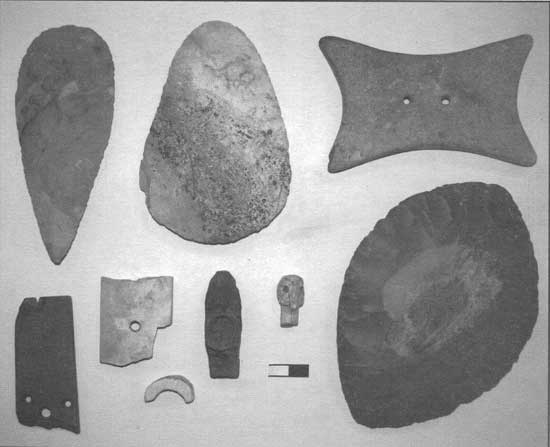

Figure 81: Middle Woodland period artifacts including cache blades

made from Burlington (Illinois), Flint Ridge (Ohio), and Wyandotte chert

(southern Indiana), drilled stone gorgets, pipe fragments and a turkey

effigy carved from bone. The small and seemingly insignificant curved

piece is a pipe fragment made from aragonite that was found in

excavation at the Mann site.

|

|

|

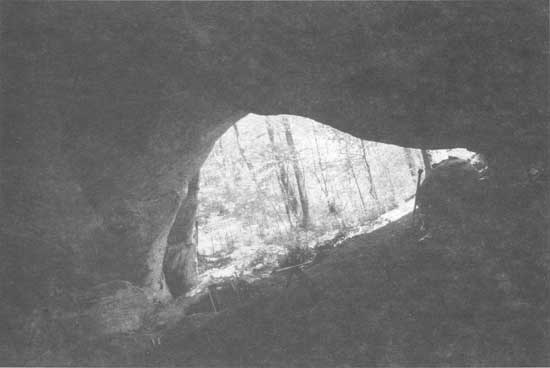

Figure 82: Excavations within the dark alcove of Arrowhead Arch. Indiana

University excavations, 1984.

|

9/hoosier/prehistory/sec6.htm

Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008 |

|