Looking at Prehistory:

Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 12,000 B.C. to 1650

|

|

Looking at Prehistory:

Late Woodland Period ca. A.D. 500 to 1500

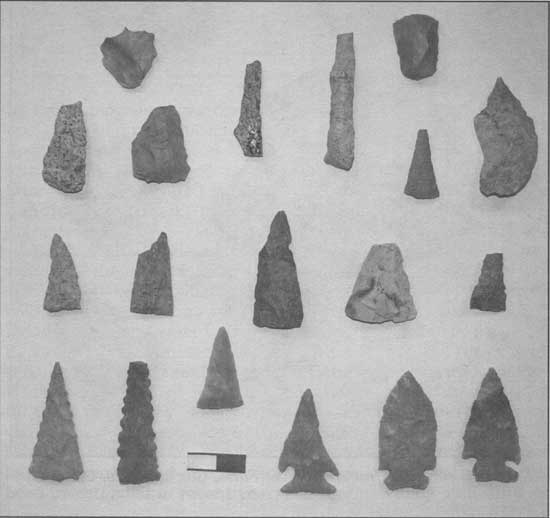

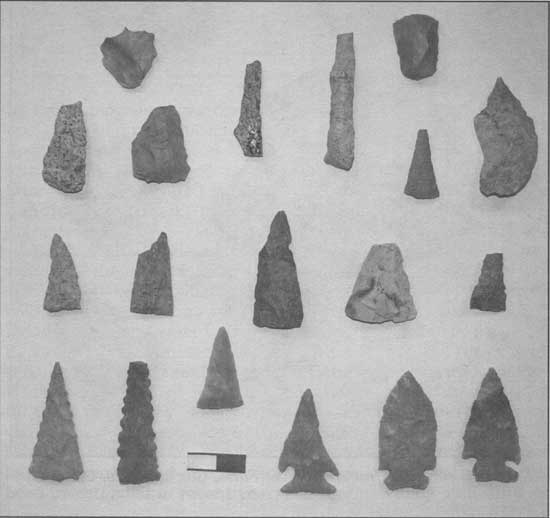

Perhaps two of the most significant occurrences that

mark the Late Woodland period are the appearance and wide-spread use of

the bow and arrow and an emphasis on growing domesticated crops and

other cultigens along with collecting wild plant foods. There is more of

a sedentary lifestyle associated with agriculture, but that does not

explain why the high ceremonialism of Hopewell comes to an end during

the Late Woodland period. A number of distinctive variations in Late

Woodland ceramics are diagnostic of the cultures or social groups they

represent, but they all include some type of stone or clay tempering.

The ceramics, along with other cultural traits, clearly separates them

from Mississippian cultures that used shell

tempering in their ceramic technology. Jack's Reef cluster (early)

and unnotched triangular points (late) become widespread

during the Late Woodland period (Figure 83). The former emphasis on the

Wyandotte chert source for tools greatly diminishes in favor of local

sources of chert. Some agricultural implements appear, along with many

kinds of cultivated foods and eventually varieties of corn, beans, and

squashes are developed and grown intensively at Mississippian sites.

There is also evidence for the increased use and size of storage pits to

preserve foods for the winter months. A number of Late Woodland phases

are known, including Oliver, Albee, Newtown, and Yankeetown. Oliver

phase and Yankeetown pottery have been identified

at camps within the hill country of the Hoosier

National Forest.

|

|

Figure 83: Arrow point variations, drills, end

scrapers, and gravers. These include Jacks Reef cluster and triangular

types from Oliver phase and other southern Indiana sites.

|

The Oliver phase people borrowed traits from Fort

Ancient tradition people who occupied southeastern Indiana, southern

Ohio, and northern Kentucky and also Springwells cultural manifestations

that extended into Indiana from the western side of Lake Erie (Figure

84). The Oliver phase is dated from A.D. 1000 to perhaps as late as

1400, overlapping with the Mississippian occupation of southern

Indiana.

|

|

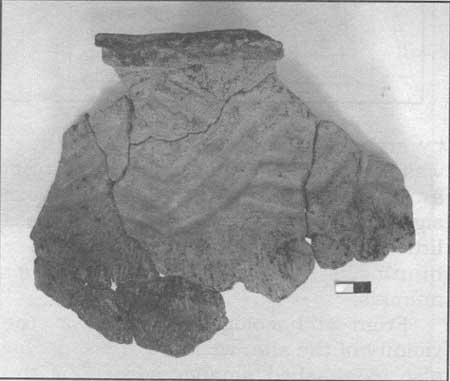

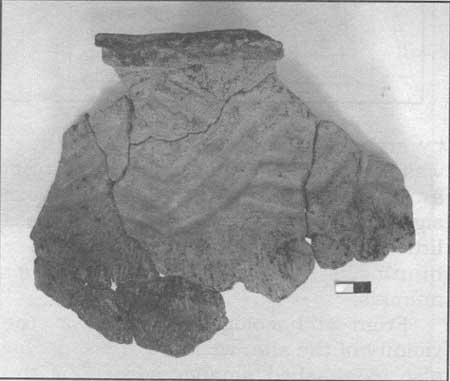

Figure 84: Oliver phase decorated ceramics from the

Oliver Farm, Cox's Woods, Clampitt, and Bowen sites.

|

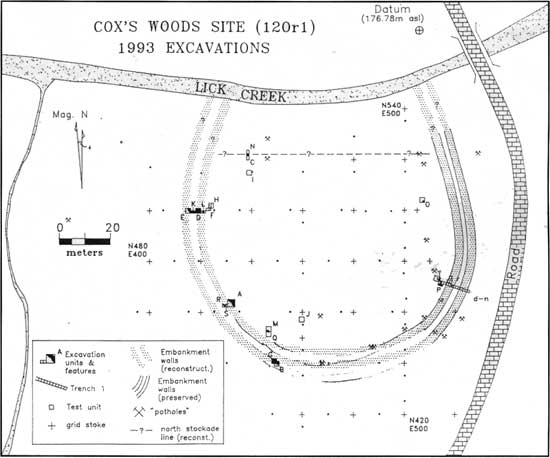

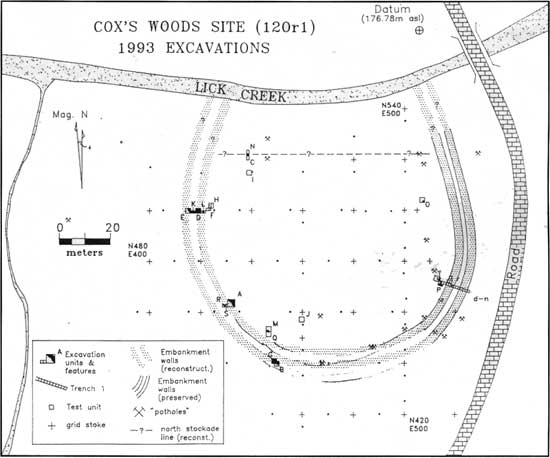

The Cox's Woods site was occupied by Oliver phase

families who built a double-walled earthen enclosure to encircle the

site and had a number of houses in a ring around a central plaza or community

area. The site is located near the Pioneer Mothers Memorial Forest on

Hoosier National Forest property, protecting one of the few remaining

stands of primary forest left in Indiana (Figure 85). Middens of refuse

accumulated within the enclosure and the surrounding area from the

remains of thousands of meals eaten by people living at the site over an

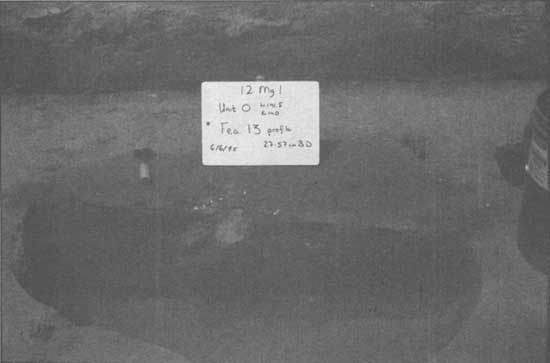

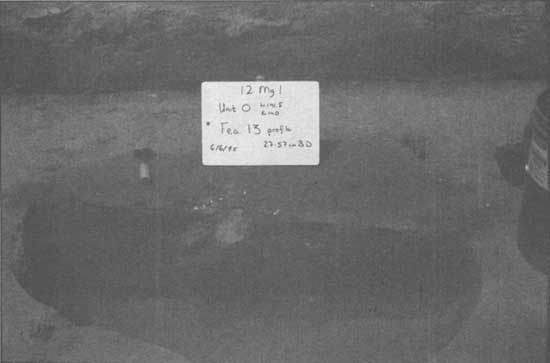

extended period of time. Excavations documented many post-molds, marked

by circular stains, following patterns indicating the locations of the

houses and also storage pits, hearths, and rock concentrations

containing artifacts such as pottery (Figures 86-87). Food remains

collected by archaeologists show corn agriculture was combined

with collected fruits, nuts and seeds and that there were significant

amounts of maygrass and little barley cultivated along with the hunting

of deer, elk, turkey and other animals.

|

|

Figure 85: The plan of the Cox's Woods site determined by limited

test excavations over selected segments of the site. Indiana University

field school, 1993.

|

|

|

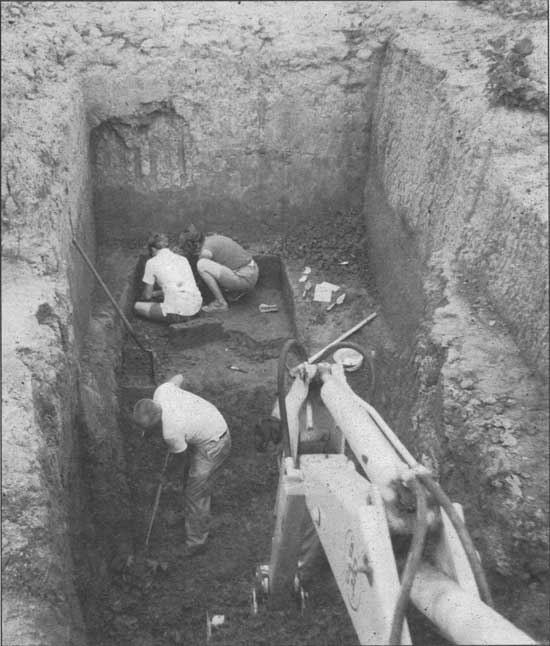

Figure 86: Ongoing excavations at the Cox's Woods site. Indiana

University field school, 1993.

|

|

|

Figure 87 (right): Rim of reconstructed ceramic vessel excavated

from the Cox's Woods site.

|

From archaeological surveys in the vicinity of the

site, we know these people also established smaller gardening and

collecting camps away from Cox's Woods. This settlement was established

in a remote location some distance from the floodplain of the East Fork

of the White River and it is suspected that future studies may show

Oliver phase village sites in other areas of the Hoosier National

Forest. Oliver phase villages located nearby and further north have been

investigated in recent years, adding

greatly to our knowledge about these people (Figures

88-90). The presence of Half Moon Spring could have been a factor in the

location of the Cox's Woods site, where the people could have extracted

salt crystals from the saline waters at the spring for cooking, the

preservation of meat and hides, as well as exchange (Figure 91).

|

|

Figure 88: A profile of an Oliver phase village in Morgan County

showing a deposit of discarded mussel shells over an old swale in the

White River floodplain. Indiana University field school, 1995.

|

|

|

Figure 89: The profile of a large Oliver phase pit

feature with artifacts and refuse and food remains. Indiana University

field school, 1995.

|

|

|

Figure 90: A large area of pit features exposed and ready for mapping at

an Oliver phase site in Johnson County. Indiana University field school,

1995.

|

|

|

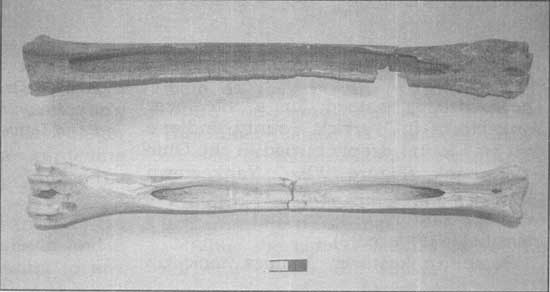

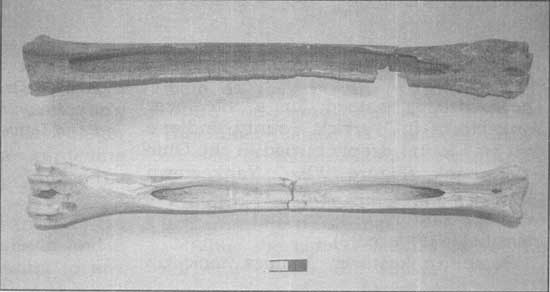

Figure 91: Deer bone "beamers" for removing the hair from animal skins

from the Oliver phase Clampitt and Bowen sites.

|

Yankeetown phase people lived within an area

encompassing the lower Ohio River Valley from southern Illinois and

nearby Kentucky, the lower Wabash Valley and into south-central

Indiana The phase is named for a site near Yankeetown in

Warrick County, Indiana that was found deeply buried in the Ohio River

bank (Figure 92). Yankeetown phase people made some of the more

aesthetic pottery designs that are easily identifiable (Figure 93).

|

|

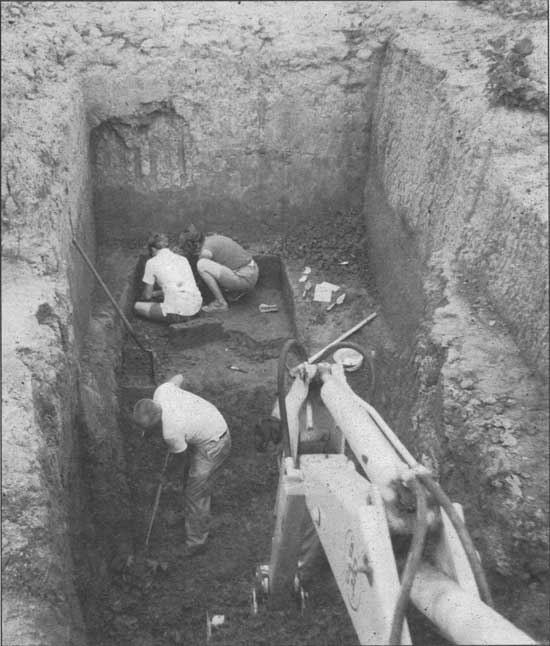

Figure 92: Deep test excavations at the

Yankeetown site, Warrick County, IN by Indiana University in 1967.

|

|

|

Figure 93: Yankeetown phase ceramics from the Yankeetown site and

Rockhouse Hollow Shelter (upper left).

|

Some Yankeetown families took up residence at Rockhouse Hollow

shelter for a limited time around A.D. 900-1000. We know this

because they left fragments of their distinctive ceramic vessels in the

shelter. There are likely to be more sites found in the future within

the Hoosier National Forest that were occupied by Yankeetown peoples.

One suspects, however, the main use of the hill country by people of the

Yankeetown phase may have been in the form of limited hunting and

collecting camps in a variety of settings, including rockshelters and

open sites. Their larger base settlements and summer gardening camps

were established along the floodplain of the Ohio River.

The other Late Woodland groups were dispersed across

central Indiana and a wider area that did not expand to any

degree into south-central Indiana. One large rim

sherd that was found in excavations within Arrowhead Arch in Crawford

County may be significant (Figures 94-95). It can be attributed to

either Oliver phase people from the north, or Fort Ancient, Anderson

phase people coming from the east near Cincinnati. This is another

example of limited use by perhaps single families that probably carried

the pottery with them as they moved up into the hill country on hunting

and collecting trips. The Albee phase is not well-known outside of

central Indiana, within the Wabash and White River drainages. The

Newtown phase is apparently restricted to southeastern Indiana.

|

|

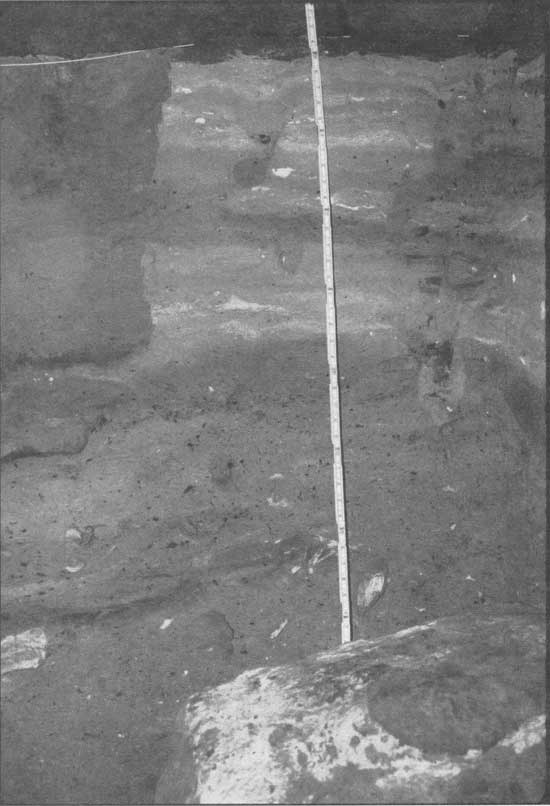

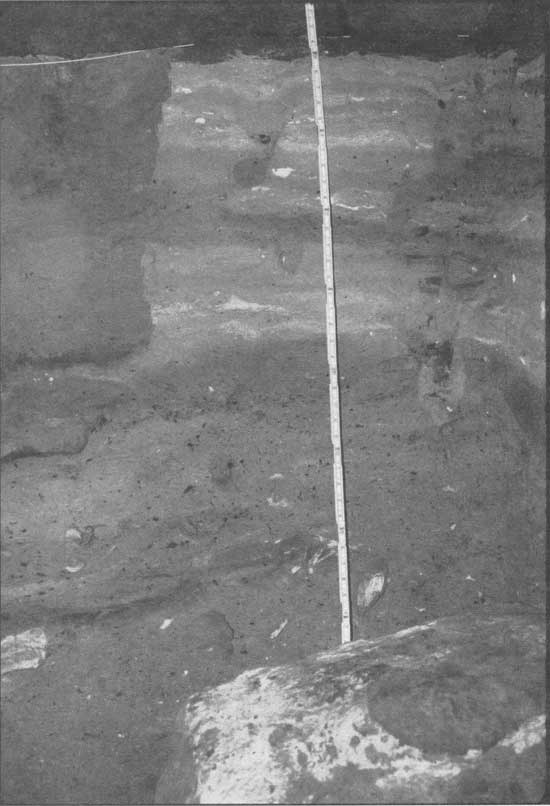

Figure 94: A profile of the deposits during

excavations at Arrowhead Arch by Indiana University in 1984. Note the

changes in soil color and consistency marking differences in the human

use of the site. The light color of the upper part is due to overlapping

ash lenses with rodent burrows. The dark area on the left marks a

looter's pit that destroyed valuable information about the sites

history.

|

|

|

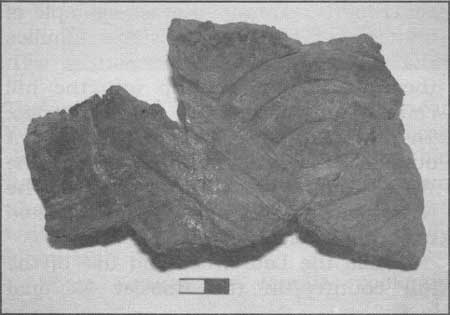

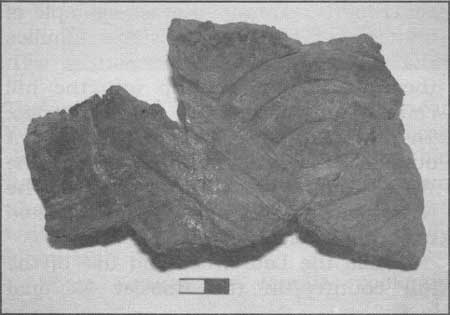

Figure 95: A reconstructed portion of a ceramic vessel recovered from

Arrowhead Arch.

|

While the Late Woodland use of the hill country in

the Hoosier National Forest may appear to be limited

compared to other prehistoric time periods, we must consider that much

is still unknown and remains to be documented. Thus, it is imperative

that interested persons, avocational archaeologists and professionals

collaborate to record information about the archaeology of the wider

region. A major effort has been underway in recent years to investigate

the many Late Woodland and other cultures that left their remains in

Indiana. Laypersons can help save important sites and information about

the prehistory of southern Indiana by reporting acts of looting and

vandalism and notifying authorities about the existence of

archaeological sites. Archaeologists rely on the good faith efforts of

the public to tell them about local discoveries so that the information

can help clarify what we know about the settlement systems of

prehistoric peoples in the Late Woodland period of the hill country and

the many cultures that came before and after this time.

While there is a temporal overlap between Late

Woodland cultures and those of the Mississippian period, many

Mississippian traits, including village organization, mound building,

trade and ceremonial habits are substantially different. Long before

Mississippian period cultures expanded north from the southeastern

United States however, many Late Woodland period cultures had evolved

from the local Middle Woodland cultures and were dispersed throughout much

of the Northeast Great Lakes, and Ohio Valley. We now know that Late

Woodland groups continued to occupy a number of areas in Indiana

throughout the following Mississippian period, and there appears to have

been interaction on a number of fronts between Late Woodland and

Mississippian groups, though each apparently retained their own cultural

identity. There is evidence at Cahokia in Illinois and other

Mississippian centers that groups with traditional Late Woodland

cultural affiliation were sometimes incorporated into Mississippian

society. One must also consider that such factors as politics,

economics, and warfare presented a dynamic situation involving groups

being incorporated and later splitting into smaller communities to live

again as they once did. Groups splitting away from a major town center

could have populated a new area or, when possible, could have returned

to an ancestral home their parents and grandparents kept alive in

stories of former times. This ebb and flow of cultural associations and

population movements probably also took place in Indiana. For

archaeologists, the specific details of cultural dynamics are difficult

to pin down because of the addition and mixing of artifacts and traits

at some archaeological sites that belong to several cultural traditions

and bridge two archaeological time periods.

9/hoosier/prehistory/sec7.htm

Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008 |

|