|

History of Nicolet National Forest, 1928-1976

|

|

I. EARLY HISTORY OF THE AREA

Any history of the Nicolet National Forest must include a look at the surrounding area, for the Forest is not a separate entity. Rather, it is an integral part of the Nation's overall resource base, and holds special meaning for the people living within and near its boundaries.

The 973,000-plus acre Nicolet Forest is located in northeastern Wisconsin — a State named for the long, meandering river which traverses it. The exact meaning of the word "Wisconsin" is not known, but some of the proposed definitions for the Indian word are "Wild," "Rushing River," and "Gathering of the Waters." The earliest written record of this word is on a 1673 map made by the French explorer Louis Joliet. Inscribed along the river line is "Riviere Misconsing."

The Wisconsin River starts at Lake Lac Vieux Desert at the Wisconsin—Michigan line on the Eastern Continental Divide. It runs southwest in a meandering direction for a distance of about 450 miles, emptying into the Mississippi River at Prairie Du Chein, Wisconsin. This river is considered one of the hardest working rivers in the Nation, with 26 power dams, paper mills and other industries using its waters.

The earliest settlers in this forested area were members of several northern Indian tribes — Chippewas, Potawatomies, Menominees and Brothertons. The Indians' first encounters with "pale face" came in the middle of the 17th Century, as French explorers pushed their way north via the rivers.

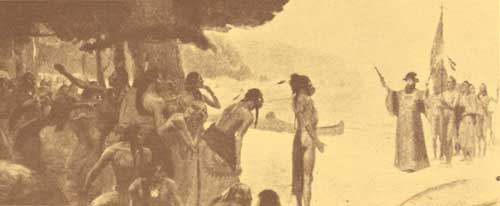

The French were the first to explore the Great Lakes region. In 1634, Jean Nicolet was sent out by the Governor of New France to promote trade with the Indians. He landed at Red Banks, near where the modern City of Green Bay is, and ascended the Fox River to a point about 20 miles west of Lake Winnebago. When he came ashore, Nicolet was met by friendly Winnebago Indians.

|

| JEAN NICOLET AND WINNEBAGO INDIANS |

Jean Nicolet is believed to have been the first European to enter Lake Michigan and travel the Great Lakes. Little was known of his explorations until the middle 1800's, when an account of his western journey was found. From this early writing, historians deducted that Nicolet traveled through the Straits of Mackinac on his way to Lake Michigan. Nicolet's party crossed the Lake to the western shore, where they met a tribe of Winnebago Indians, with whom Nicolet made a peace treaty.

Nicolet was born in Cherbourg, France. He came to America for the first time at the age of 20, with explorer Samuel D. Champlain. Nicolet settled in Canada with a tribe of Indians. He studied their language and later served as an interpreter for Champlain. Nicolet's Lake Michigan crossing was his first and last venture on the Great Lakes. His boat overturned on the St. Lawrence River during a storm and he drowned.

The Nicolet National Forest is named in honor of this early explorer.

Twenty years after Nicolet set foot on the Wisconsin shorelines, two fur traders, Radisson and Groseilliers, took to the Fox River. Their excursions encouraged river travel and gave a push to the first real "industry" of the north woods — fur trading.

The many lakes and streams which dot and criss-cross this northern Forest, at one time provided an ideal habitat for a multitude of fur bearing animals, as well as a natural transportation system. Trading posts soon dotted the shores, and, in 1669, a mission was established a few miles above the mouth of the Fox River. This was the first permanent settlement within the present Wisconsin boundaries. Today the City of DePere is located here.

|

| INDIANS IN FRONT OF THEIR HOMEMADE TEPEE OR SHELTER |

Early trading posts were located on the Wolf River between the villages of Langlade and Hollister; on Pine Lake at Hiles; on the shore of Virgin Lake (6 miles east of Three Lakes); on the east shore of Catfish Lake in the Chain of Lakes; and, at the old Indian village on Lake Lac Vieux Desert. Here, the art of bartering was kept alive, as the traders obtained furs from the Indians in exchange for trinkets, guns, ammunition and "fire water" (whiskey). The furs were then transported, via the waterways, to a post where they were sold and shipped to Europe.

As explorers, fur traders, and finally the settlers advanced into the area, the Indians were driven from the land.

Misdealings between fur traders, settlers and the Indians caused bad feelings, which culminated in the French and Indian War. In 1765, the war ended, and French possessions east of the Mississippi River were ceded to England.

Several years later, the colonists went to war with England. At the end of the American Revolution, the territory northwest of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River was given to the new United States by Great Britain. However, England did not relinquish its hold immediately, and it was not until the close of the War of 1812, that she ceased to exercise some degree of control in this territory.

In 1787, the region bounded by Pennsylvania, the Ohio River, the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes was organized as the Northwest Territory. The claims of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Virginia, as based on their early charters, were returned to the United States between 1781 and 1786. The Wisconsin area was originally included in the organized territory of Indiana in 1800. In 1809, it became a part of the Illinois Territory, and in 1818, when Illinois became a State, the area was added to the Michigan Territory.

No recounting of those early fur trading days would be complete without mentioning Daniel Gagen. He was one of the notable pioneers of northern Wisconsin. The Village of Gagen, in Oneida County, is named in his honor.

Dan Gagen was born in England in 1834. He came to America in 1851, at the age of 17. Although he had obtained a good business education in England, he spent his first year working in the copper mines of northern Michigan. The country was wild in those days, with the Indians and settlers tolerating each other because of their interdependence. The Indians depended on the settlers for supplies, while the furs procured by Indian hunters and trappers found a ready sale in civilized marts, providing the settlers with a source of income.

The fur trading profession appealed to Gagen, and he soon quit his job in the mines, and built a log cabin trading post about 2 miles from the present town of Eagle River.

During the early 1860's, Gagen carried on an extensive business with the Indians. He made horse team trips from his post to Berlin, in Green Lake County, where he sold his furs to L. S. Cohn. (Cohn later built an addition to the City of Rhinelander, which is still known as Cohn's addition.)

Gagen was also a good friend of the Indians, and he often acted as arbitrator or judge in matters of dispute between the Indians and other residents. His fame extended throughout the State.

Toward the close of the Civil War, the fur business began to drop off, and Gagen drifted into the lumber business. He also took up farming and established a home at Pine Lake. For years, Gagen was a member of the county board. He was a man of such prominence and influence, that he was often referred to as "King of the North." Around 1896, Gagen moved his family to Three Lakes, Wisconsin. This town remained his home until his death on November 25, 1908. His wife and two sons, James, a former resident of Antigo, and Henry of Three Lakes, were with him when he died.

Wisconsin was organized as a separate territory in 1836. At that time, it included the area which makes up the present States of Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa, as well as those portions of North and South Dakota lying east of the Missouri and White Earth Rivers. Wisconsin, with its present boundaries, became a State of the Union in May 1848.

|

| JOHN SHOPODOCK |

One of the most colorful figures from the pages of Nicolet Forest history was John Shopodock, a Potawatomi Indian Chief.

I met the Chief for the first time while on a fishing trip at Windsor Dam on the North Branch of the Pine River in 1929. He spoke fairly good English and was quite inquisitive, though he gave very little information out about himself during the course of our conversation.

Up until his death in 1940, Chief Shopodock lived on the North Branch of the Pine River, within the Nicolet National Forest boundary. Although the government gave him 40 acres of land in the NE NE, Section 22, T40N, R13E, and built him a large frame building on the site, the Chief continued to live in his hillside dugout. He did, however, use the frame structure in the fall of the year to house from 6 to 8 squaws while they stayed with him and cut marsh hay for his wild Indian ponies.

Around 1930, the Humane Society made the Chief sell his wild ponies, because he didn't have enough hay to feed them, nor a shelter to keep them in during the harsh winter months. A man from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, came in the spring of that year and offered to purchase the horses. After the man captured the herd, he took them away to resell. He failed to pay Chief Shopodock. When the Chief didn't get his money as promised, he began walking to Milwaukee to collect it in person. En route, the Chief stopped in Marion, where he hoped to borrow some money until his return. When the banker asked him for collateral, the Chief said, "What you mean collateral?" The banker explained, and the Chief said, "I got 100 horses."

Chief Shopodock got the loan and continued on to Milwaukee, where he collected his money. Upon his return, the Chief stopped at the Marion bank to repay his loan. He had quite a lot of money left over, and the banker suggested he leave some of it at the bank for safe keeping. The Chief looked at the banker and said to him, "How many horses you got?" Needless to say, the bank didn't get a "loan." The last time I saw Chief Shopodock was at the Alvin Civilian Conservation Corps Camp in 1937. He ate a meal in the mess hall with us, and was given a loaf of bread to take with him.

On January 28, 1940, Chief Shopodock walked to Kelsey's store on State Highway 55 near the Pine River to buy supplies. After making his purchases, Chief Shopodock was given a ride to the road leading to his cabin by the Kelseys, and left off in a snowstorm. When the Chief did not return the following week for supplies, the Kelseys went in search of him. They found his frozen body February 6, some 30 feet from his cabin door.

Chief Shopodock is buried in the Indian Cemetery at Wabeno, Wisconsin. His heirs still own the 40 acres of land given the Chief by the Government.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

9/nicolet/history/chap1.htm Last Updated: 08-Dec-2009 |