|

History of Nicolet National Forest, 1928-1976

|

|

II. SETTLING THE AREA

EARLY TRAILS

Vital to any frontier establishment was a transportation system which provided residents with relatively fast and efficient access to other civilization strongholds. Although the waterways of the north were the first travel routes, as people moved farther inland, they became less accessible. A series of foot and horse trails soon developed between the frontier villages.

The Ontonagon Mail Trail was a well trodden trail in the 1800's. The road began where the City of Wausau is today, and ran through Jenny (now Merrill), north through Pelican Rapids (now Rhinelander), along the west side of Columbus Lake (an old bachelor named Alex Columbus had built a log shanty on the west side of the lake, hence the name), then north to Gagen Hill. The road crossed the Eagle River near Morey's Resort. A mail route was established along this trail, running between Wausau, Wisconsin, and Ontonagon, Michigan. In those days, mail was back packed by men during the milder months, and dog trains used in the winter.

Due to the regular use of the Ontonagon Mail Trail, resting stations were set up. John Curran, formerly of Rhinelander, manned the Pelican Rapids station. Dan Gagen, who was mentioned earlier, managed the next station which was located about 30 miles away at Gagen Hill.

In 1854, A. B. Smith lead a crew of men who cut out a road from Wausau to Jenny; the section from Stevens Point to Wausau was completed the year before. In the fall of 1857, Helms Company of Stevens Point cut out a "tote" road from Grandfather Falls to Eagle River. The Government appropriated certain lands in 1860 for the construction of a road from Jenny to Lac Vieux Desert, via Pelican Rapids and Eagle River. The road was turned over to the County, which in turn, appropriated $3,000 in tax certificates for the work. This completed route was known as the Wausau and North State Line Road.

The Lake Superior Trail was used only during the winter months for hauling mail and supplies and driving cattle to the copper mines in Michigan. The trail started at Shawano, Wisconsin, and followed the west side of the Wolf River north to the Wisconsin State line. Much of this section was impassable during the summer because there were no bridges or water crossings and many of the swamp areas were too wet to cross. The trail crossed to the east side of the River at what is commonly known as the "Henry Strauss Crossing." It then ran between Twin Lakes, crossing Pickeral Creek and continuing on to Rockland, Michigan. The Lake Superior Trail was built between 1861 and 1862.

When the timber companies penetrated Langlade County, it was essential that the camps keep in touch with their supply bases, which were usually located at Wausau, Appleton or Shawano, This opened the "tote" road era. The hardy lumberjacks cut out a narrow path that was barely wide enough to accommodate the yokes of oxen and horses. These tote roads were not straightened until some time after the General Land Office survey was completed in the 1860's. The old Indian trails were gradually forced out of existence by the tote roads, which, have themselves, become a thing of the past.

The Military Road is of major historical importance to the Nicolet Forest, and it is still a popular Forest route. It was built to transport military forces from Fort Howard in Green Bay, Wisconsin, to Fort Wilkins in Keweenaw County, Michigan, during the Civil War.

In the early days of the War Between the States, the North had no way of transporting troops from the interior to the Canadian boundary, should trouble break out with the Indians. Thus, on March 3, 1863, Congress passed an Act approving the construction of a military road from Fort Howard to Fort Wilkins. Public lands were granted to the States of Wisconsin and Michigan to aid in the construction.

On April 4, 1864, the Wisconsin Legislature accepted the land grant and appointed commissioners to lay out the road, advertise for bids and award the contract. All construction work was paid for with land grants, 3 sections for each mile of completed road.

James M. Winslow was given the contract on August 24, 1864. He transferred it to the U. S. Military Road Company, a corporation organized under Wisconsin law. This company, in turn, assigned the contract to Jackson Hadley, with the transfer being approved by the legislature. Hadley died March 2, 1867, having completed only 30 miles of the road. Ninety sections of land were turned over to Mrs. Augusta Hadley, widow and administrator of the deceased's affairs. Mrs. Hadley later turned the 90 sections of land over to A. G. Crowell, with whom she had entered into a contract for the remaining road construction.

|

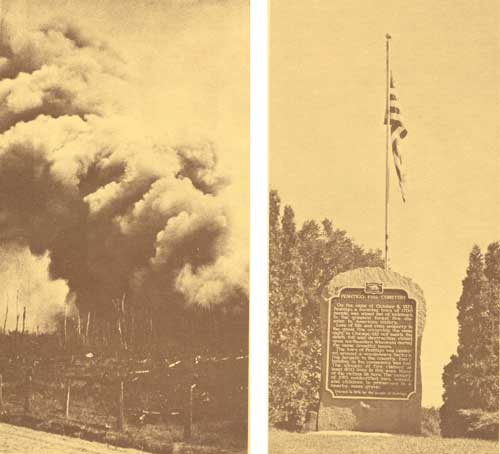

| EARLY MILITARY ROAD (left); PLAQUE OF MILITARY ROAD — 1965 (right) |

Meanwhile, Congress extended the completion date from August 24, 1868, to March 1, 1870. Crowell and his business partners, John W. Babcock and B. N. Fletcher, completed 52.5 miles of the road by January 1, 1868. They then entered a contract with Alanson J. Fox and Abijah Weston of Painted Post, New York, giving them half interest in the uncompleted road. On February 20, 1870, the commissioners reported to Governor Fairchild, that Babcock, Fox and Weston had completed the unconstructed portion of the road within the allotted time. Crowell and his heirs were granted 38,017.17 acres of land in Langlade County (then part of Oconto County).

More than any other wagon road, the "Old Militare" opened up a vast expanse of the Wolf River country to early traders, stimulating and increasing the momentum of the great lumbering industry in eastern Langlade County and the now Nicolet National Forest. While the Military Road was originally intended for military defense of the Nation, woodsmen who worked in the Wisconsin pineries a half century ago refute this; they insist the Military Road was a land and timber conspiracy.

The old Military Road ran through a region rich in natural resources. For example, it was not uncommon for a fur trader to purchase $10,000 worth of furs from the Indians in a single season, obtaining bear, wolf, beaver, otter, fisher, marten, and mink pelts. Faced with a market hungry for quality furs, the hunters and trappers stepped up their activities, and within a few years, the fur industry was destroyed. Today, the fur bearing animals have nearly disappeared, and efforts are being made to restore the delicate balance of long ago.

Although the wildlife populations of Wisconsin's north woods had been ravaged and the fur traders forced to move to other parts of the Country, the forests were not yet safe from man. Towering pine trees stood at the mercy of the saw.

TIMBER TALES

Following close behind the fur traders were the lumbermen. The timber industry was established in northern Wisconsin over 100 years ago, with the first pines being harvested on the upper waters of the Wolf and Wisconsin Rivers.

The first timber cut on lands now making up the Nicolet National Forest consisted of pine logs taken around 1835. A sawmill firm in Neenah took the first pines from the northern part of Oconto County and floated them down the Wolf River to the mill. In 1838, a water power mill was built at Peshtigo in Marinette County. Pine logs cut from the northern part of Oconto County were floated down the Peshtigo River to this mill. Several sawmills were built at Green Bay and Oconto between 1840 and 1860. Pine logs were driven down the waterways, from what is today the Nicolet National Forest's Lakewood District, to supply these mills.

In 1842, the first raft of pine logs from Forest County was floated down the Rat River. By the mid-1840's, four mills were in operation in Neenah. Oshkosh had half a dozen sawmills by 1850.

|

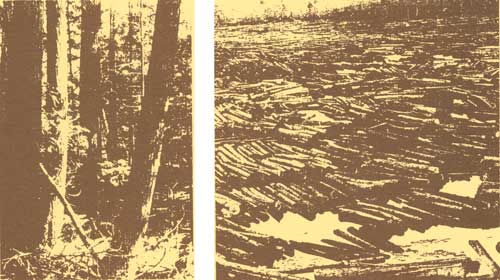

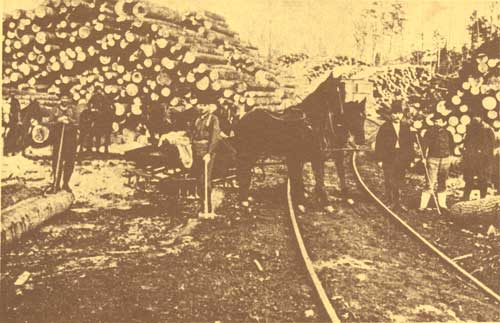

| THE VIRGIN NORTH WOODS (left); LOG DRIVE ON ONE OF THE RIVERS (right) |

The first logging in Vilas County was done adjacent to the Eagle Chain of Lakes in the spring of 1856, by Fox & Helms. Their first logging camp was located just west of where the present iron bridge crosses Eagle River on the approach to Hemlock Resort.

Logging activities moved north of the Tomahawk River in the winter of 1857-58. In the fall of 1857, Helms & Company cut the first "tote" road from Grandfather Falls to Eagle River. The crew arrived at Eagle Lake on New Year's Day, 1858. The company banked about 20,000 logs that winter, and drove them to Mosinee to be sawed. In the winter of 1859-60, Hurley & Burns began logging along the shore of Eagle River and the Three Lakes Chain of Lakes. The Edwards & Clinton Timber Company also began operations in this area that same year. Both companies had mills below Grand Rapids (now Wisconsin Rapids) and drove the logs to their mills.

By 1866, all the pine timber located close to streams and lakes had been cut. With the coming of the railroad, the door was opened for heavy exploitation of the wood resource in northern Wisconsin. As the railroad companies laid their tracks, they also created the means for full scale logging of the area's hardwoods. The Soo Line Railroad was built through the middle of the not yet designated Nicolet Forest in 1887, going through Cavour, Argonne and on to Gagen. Later, a spur was built from Argonne to Shawano, going south along the west side of the now Nicolet Forest. Today, this main line runs from the Michigan Soo line to Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota. The Chicago Northwestern built lines from Monico to Three Lakes in the early 1880's. The company then put down track north through Eagle River, Conover, Land O'Lakes, and on to Watersmeet, Michigan. Spur lines were later built by this company into Hiles and Phelps, Wisconsin.

|

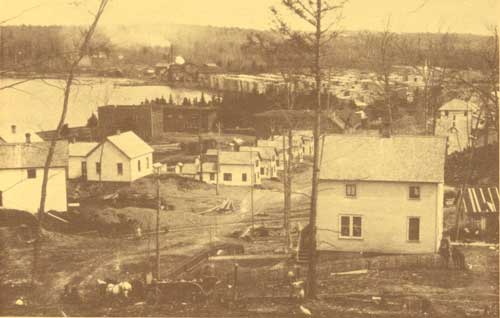

| EARLY VIEW OF MAIN STREET (left); GETTING THE LOGS TO MARKET (right) |

The Hiles spur was abandoned around 1934, but the Phelps spur is still in existence. Towns developed along the Chicago Northwestern Railroad, and some of these still exist today: Mountain, Lakewood, Townsend, Carter, Soperton, Wabeno, Padus, Blackwell Junction, Laona, Cavour, Newald, Popple River, Long Lake and Tipler. All of these towns began as logging or sawmill centers along this railway system.

Great lumber firms, such as Hackley—Phelps—Bonnell; Paine Lumber Company; Sawyer-Goodman; Wells Lumber Company; Connor, Holt, Oconto Company; and many others flourished. Of these firms, only Connor is still operating its mill in the town of Laona within the Nicolet National Forest. The Goodman mill is still operating under another ownership in the Town of Goodman east of the Forest.

Pine lumbering activities continued to increase, until by the late 1800's, all the principal rivers and tributaries draining the current Nicolet Forest area were packed full each spring with choice pine logs destined for mills in Oshkosh, Oconto, Green Bay, Menominee and Marinette.

Many dams were constructed on rivers in northern Wisconsin to help hold back the water until needed to carry the pine sawlogs down the streams. In fact, a ditch was dug between Franklin and Butternut Lakes to supply the North Branch of the Pine River with a large volume of water during floating time. Many of these old dam sites are still visible, with some of the old dam timbers still in their original places in the streams, fastened with large drift pins.

Lumbering reached its peak in 1899, thanks to the railroads. In that year, Wisconsin produced more than 3 billion board feet of lumber. The timber industry continued at a high level until the early 1900's, when the great stands of pine, which many people thought were inexhaustible, disappeared.

Following the decline of the pine lumbering industry, two other forest industries sprang up, pushing man farther into the northern forests. The hardwood-hemlock lumber and the wood pulp and paper industries encouraged new sawmill towns, which were transient in character. Hardwood logs could not be driven downstream because they didn't float well and the cost of rail transportation gradually became too high; therefore, the sawmills had to follow the harvesters. Early pulp and paper mills were built upriver at water power sites. The Fox, Menominee, Oconto, Wisconsin and Chippewa Rivers furnished power for many of these early pulp and paper mills.

After the timber was cut, fires were set to the slash to eliminate the threat of uncontrolled forest fires. Many of the lands were burned repeatedly, permitting the introduction of such pioneer species as aspen, white birch and jack pine. Aspen was considered a weed tree until the 1930's, when research developed methods for making paper from hardwoods. Today, in the Lake States, more paper is made from aspen than any other species.

History is made, not so much by events, as by people. The following is a list of some of those people who worked as timber cruisers during the heyday of northern Wisconsin's timber industry:

| NAME | HOME TOWN |

| John Emmett Nelligan | Oconto |

| James (Jimmy) George | Shawano |

| J. L. Whitehouse | Shawano |

| Charles Bacon | Crandon |

| Robert Delaney | Antigo |

| Ernest Norm (also local storekeeper) | Bryant |

| George Jackson | Pickeral |

| Fred Kalkofen | Antigo |

| Charles Larselere | Lily |

| W. J. Zahl | Langlade County |

| Dave Edick | Antigo |

| Charles Ainsworth | Pearson |

| Charles Worden | Menasha |

| Earl Weed | Menasha |

| B. F. Dorr (also surveyor) | Langlade County |

| E. S. Brooks (also surveyor) | Kempster |

| Nate Bruce | Parish |

| S. A. Taylor | — |

| W. C. Webley | Wausau |

| Chester Bennett | Green Bay |

| Abner Rollo, Sr. | Antigo |

| Reuben Vaughen | — |

| Peter O'Connor | Menasha |

| Dan Graham | Eagle River |

| James Hafner | Wausau |

| Phil Ryan | Summit Lake |

| A. J. Miltmore | Town of Vilas |

| Cassius Smith | — |

| Gates Saxton | — |

| George Schultz | — |

| Jess Calwell | Oconto |

| Malcolm Hutchinson | Malcolm |

| Oso Campbell | Antigo |

| Joe Fermanich | Mattoon |

| George Stout | Rhinelander |

| M. I. McEachin | Rhinelander |

| George Baldwin | Appleton |

| Bryon Kent | Oconto |

| George Glenn | Crandon |

| John Gayheart | Wabeno |

| John Hammes | Padus |

| Pat Sullivan | Three Lakes |

John Emmett Nelligan was one of the earliest cruisers in the area. He worked for many different logging companies and later became a logger himself. His logging camps were along the Oconto, Waupee, Wolf, and Pine Rivers. Nelligan Lake is named after him.

Many of the early employees on the Nicolet National Forest knew John Hammes and Byron Kent as two of the old wood cruisers. I examined lands for purchase on the Nicolet in the winters of 1933 and 1934 with them.

There are many others who were early timber cruisers — too many, in fact, to list. These old timers were sometimes called timber "lookers" and usually worked with a compassman. Plots were randomly selected, and the number of trees per species were then tallied. The number of logs per tree was estimated next. The cruiser then figured out how many logs would make a thousand board feet, and arrive at the final estimate.

The following poem appeared in the Forest Republican of Crandon, Wisconsin, in 1965. It reflects much of the jargon, lifestyle and attitudes of the timbering years.

TIMBER

Timber! . . . . . Ho!

by

Bruce H. Schmidt

Oh come all you buck-ohs and lend me an ear

As we turn back the pages for many a year.

To the days when the jacks were cutting tall timber.

It's part of the past, but the memory's linger.

To sing of the cross-cut, the whang of the axe,

The sweat of the brow and the ache in the back.

Then hitch Dan and Mag get-ee-up, get, ee-awmp.

The sun isn't up, but it's light in the swamp.

It's up in the morning to rise and to shine,

And start down the tote road that leads to the pine.

Now here comes a jack we remember as Hank;

With an old team of nags and a full water tank.

It's frosty and cold as clear as a bell.

And he ices the tracks til they're slippery as hell.

Then hook to the jammer and jerk the logs high.

And deck the sleigh loads 'til they're up to the sky.

Then crawl up on top, and it's crowing eleven;

As you start for the landing at two-forty-seven.

(The old ways of logging aren't found in a book.

Now, who can throw cats paw, or set a swamp hook?

The hydraulic loader's the tool of the time—

Jack moved bigger logs with a double deck-line.)

Off on the right, two jacks make a dash.

You hear the cry — tim — ber, and see the tree crash.

Mag picks up her ears, and lets out a neigh.

And a horse with a travois comes down the skid-way.

The pads of the snowshoe have made fairy rings,

Yon wiley weasel wears coat for a king.

From a furry of fluff comes a Chick-a-dee-dee.

And a whiskey-jack shrills from a yellow birch tree.

As you pull into the spur on the Soo,

The cookee is beating the triangle, too.

He throws back his head and yells, "Come and get it."

You'd better be quick, or you might well forget it.

Then loosen the binders and let the logs roll,

To the man on the cross-haul, Resinski, the Pole.

With hammer on anvil the smith makes it ring.

And the crew in the sawmill are making it sing.

The carriage is rolling; the saw slabs the pine,

and the clerk in the office is keeping the time.

At the end of the day it's to the bunk shack;

There's mittens and socks drying out on the rack.

The air's full of smoke, and it gets rather dense.

Mixed with many a yarn spun from the deacon's bench.

You work and you work, that's all that you do.

'Til spring break-up comes, and you know that you're through.

They figger your time, and you draw up your pay

At ten cents an hour; ten hours a day.

Then you pack up your turkey and head into town.

Every jack in the country side's sure to be found.

Jack Holland, Jack Toole, and Jack the Sinard.

And dozens of others lined up at the bars.

There's Black Joe and Red Jim, and Dick the Saville.

And Big Hans and Shorty, and the one-armed Bill.

There's Irishers, Bo-hunks and there are the Swedes,

And a salt shaker sprinkling of all other breeds.

They're rugged and tough and rough as a cob.

And they'll fight one another, or all in a mob.

In the world of lumberjacks, women were few.

There was trapper Nora, whom likely you knew;

As Swamp Angel or Spirit of Two Forty Seven.

And Polly, whose cooking, full attention was given.

The jacks in the region of Porcupine Hill,

Who hankered for something that came from a still.

And also the sight of a woman again,

Found whiskey and Marge at the old Old Pine Tree Inn.

There were loggers who hired the crews.

The list is too long to name but a few.

The big ones like Connors, Brown Bros., and Hiles

Whose holdings spread out over the miles.

And small ones like Rindal, Garlock and Hess, Palmer and Tyler and Johnny the Jess.

And down through the years on the end of the list,

A little Swede jobber, called Maggie the Quist.

The life of the lumberjack wasn't a joke.

He'd liquor and rampage until he was broke.

And we can't recollect if ever we knew,

How in the devil he'd summer it through.

But along in the fall when things came alive

It was back to the camps, like bees to a hive!

Back to the woods he'd head like a bee,

Though the life was a hard one his spirit was free.

One thing we think we can state as a fact,

There were many exploited the low lumberjack.

We're not here to judge — was it right — was it wrong?

Just to tell you their story — that's all of the song.

In the woods of the north, we have lumberjacks yet.

A second growth crop of a different set.

The original timber has passed through the landing;

Except gnarled rampikes; that still may be standing.

Jack, as we know him, has taken his fall.

And has faded away with the echoing call . . .

Tim — ber!

Early Loggers Referred to in Poem

Albert Hess — Cavour, Wisconsin

George Palmer — Argonne, Wisconsin

Tom Tyler — Crandon, Wisconsin

John Jessie — Argonne, Wisconsin

Magnus Soquist — Argonne, Wisconsin

Burt Garlock — Argonne, Wisconsin

It wasn't long after the mills were built and running that the logging camps began to be replaced by permanent settlements. Many of these early logging towns now lay within the Nicolet Forest boundaries and have played a vital role in the area's history. The following towns offer an over-all look at early forest settlement: Lakewood, Wabeno, Laona, Hiles, Phelps, Cavour and Tipler.

LAKEWOOD

Lakewood is located in the southern portion of the Nicolet National Forest, where some of the first pine logging was underway by the late 1800's. Originally organized as Wheeler, Wisconsin, in 1890, the name was changed to Lakewood in 1930. The town's first school was built on the site of an old Holt & Balcomb logging camp, about 1.5 miles east of the present town. This original log building is still standing and serves as a small museum.

|

| VILLAGE OF LAKEWOOD — 1920 |

Chicago & Northwestern Railroad track was laid north into the area in 1898. Later, State Highway 32 was built into the area, forcing the citizens to gradually relocate to the town's present location. The Nicolet National Forest's Lakewood Ranger District is headquartered here.

WABENO

The early history of Wabeno centers around the development of three lumber companies — Menominee Bay Shore Lumber Company, A. E. Rusch Company and the Jones Lumber Company.

In the closing years of the 1800's, the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad pushed north into the area, which had already been exploited by the pine lumbering interests. Sawmills were soon built along the tracks, and a town sprang up around them. Wood fueled the community's economy. Together, the Menominee Bay Shore, A. E. Rusch, and Jones companies produced more than 35 million feet of lumber a year.

All but the Menominee Bay Shore mill shut down between 1920 and 1930. In 1936, it, too, was forced to close its door, being faced with hundreds of slashed and burned acres. This company is considered one of the most destructive ever to have operated in northern Wisconsin, its slash and burn policy leaving much of the land devastated. Company officials had hoped to sell these cutover and burned lands to prospective farmers, but the market never developed.

On June 2, 1880, a tornado swept across northern Wisconsin from Antigo to Lake Superior, causing timber to blow down in a strip that measured one-half to one mile wide. This area was called "Waubeno," or "The Coming of the Winds" by the Indians. The town took its name from this event.

LAONA

The turn of the Century marked the founding of Laona — just 20 years prior to logging's heyday. Around 1876, the pine loggers came into the area and cleared off the pine stands which were scattered throughout the hardwoods. Not until the railroad came to Laona in 1900, however, did the great logging operations in the hardwoods begin. Exploratory expeditions into this area by pine loggers and a few other individuals took place be tween 1870 and 1890. The area was not very accessible, and few men ventured this far from the last outposts. Eventually, logging expeditions moved into the area, with pine being hauled on sleighs to Roberts Lake and floated down the Wolf River, or put in the Peshtigo River below Taylor Falls.

During the last decade of the 19th Century, W. D. Connor hiked, with his cruisers, examining the fine stands of hardwood timber which he later purchased. Also, during this period the Chicago Northwestern Railroad was moving northward into the Laona area, a project which benefited from receiving huge Federal land grants. The initial logging of the area occurred between 1900 and 1910. Oxen were used to skid the logs, while the hauling was done with sleighs and horses on iced roads. In later years, the "snow snake" was used on some operations. The "snow snake" was a steam powered caterpillar with front-end runners for steering. Used on ice roads, it could haul several sleighs of logs at one time.

|

| "TRAIN'S A'COMIN!" |

|

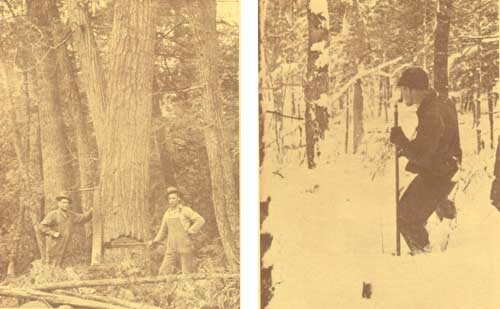

| EARLY LUMBERJACKS (left); SURVEYING THE NORTH (right) |

|

| THE STEAM HAULER — CALLED SNOW SNAKE |

|

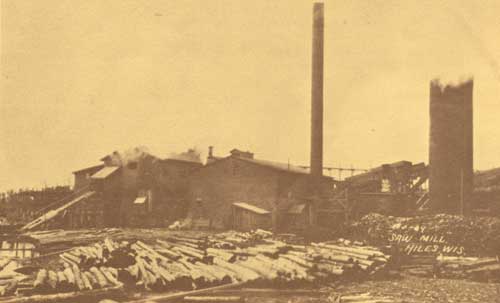

| LAONA SAWMILL |

The Connor Lumber and Land Company built its first sawmill in 1901, and had two band saws and one re-saw. The mill later burned to the ground, but was rebuilt. Logging camps sprang up throughout the entire area and encouraged the rapid development of Laona.

During the second decade, 1910 to 1920, railroad logging was expanded, and rapidly replaced the sleigh and "snow snake." This was the "heyday" of logging in the Laona area, with millions of board feet of timber felled by hundreds of lumberjacks who worked from dawn to dark. The lumber production of the Connor mill steadily increased until its maximum capacity had been reached.

The first settler in Laona was Norman Johnson. His daughter, Laona, was the first white child born in this town, and the town was named in her honor.

HILES

Although the timber industry eventually played a big part in putting Hiles on the map, this town had its first beginnings as a trading post. In 1860, Dan Gagen established a trading post on the banks of Pine Lake along the Military Road. Gagen sold the post to J. B. Thompson of Wausau in 1863, at which time H. B. Fessenden of Argonne moved in, making him the first settler in the area. Fessenden bought the site, and sold it to Franklin P. Hiles of Milwaukee in 1902.

Hiles was instrumental in bringing a branch railroad from the Chicago and Northwestern's main line into the area. Once he erected a sawmill, store and hotel, Hiles was on its way to becoming a thriving frontier town.

Hiles was organized in 1903. The first town officers were: E. Tarbox, chairman; Paul Rayfield, treasurer; Jack Nolan, assessor; and C. Walaken, clerk. Land was taken from the towns of Crandon and North Crandon to help organize Hiles; but, in 1906, two townships were taken away from the area and added to Vilas County. Within a few years, Hiles sold all his business and personal holdings to the Foerster Whitman Lumber Company. Whitman later sold out to a Mr. Mueller, and the company became the Foerster Mueller Lumber Company of Milwaukee. This firm made considerable improvements in Hiles, including building many homes for its employees.

In 1919, C. W. Fish bought the entire Hiles property. Under his management, the town was given great care; streets were repaired, sidewalks put in and trees planted. A new church was built in 1924, along with a modern school building. The old street lights were replaced by a "white way" of electric lights which ran on power generated at the sawmill, the town's only source of electricity at the time. They shone brightly from 6:00 a.m. to 9:50 p.m., when they were blinked as a signal that the lights would be turned off at 10:00 p.m.

|

| MAKING UP THE LOG TRAIN |

|

| COMPANY HOUSES AND CHURCH IN HILES — 1928 |

|

| HILES SAWMILL |

|

| TRAINLOAD OF LOGS BEING BROUGHT INTO HILES SAWMILL |

Hiles continued as a modern, thriving town until the Depression hit the area in 1932. The lumber mill finally shut down in August 1932, leaving only part of the company in operation for sporadic periods of time from then on. The Depression forced Hiles to become a summer resort and farm town, rather than a lumber manufacturing center.

The Federal Government established a home for unemployed transients in Hiles in 1933. From 300 to 500 men were housed in the old boarding house and post office building, while they worked on roadside cleanup projects in the Nicolet National Forest. Unfortunately, the transient home was destroyed by fire in February, 1934, and it was finally closed in June, 1934.

PHELPS

Phelps, Wisconsin began as a post office, erected in 1903. The town was known as Hackley, until 1910, when the name was changed to Phelps, after the owner of the local sawmill.

Lumbering was the sole industry in those early years. Hackley, Phelps, Bonnell Lumber Company built a sawmill in 1903, adding a large chemical plant 3 years later. Logs were processed at the Phelps mill, after being brought in by company-owned railroads. The original mill burned in October, 1916, but was rebuilt. It resumed operations November 11, 1917.

(Note: Today, the Rideout Farm is located at the site of Logging Camp #1.)

|

| TOWN OF HACKLEY — LATER NAMED PHELPS — 1908 |

|

| FIRST SAWMILL IN HACKLEY — NAME LATER CHANGED TO PHELPS |

William A. Phelps, company general manager, died in 1912. His son, Charles A. Phelps assumed the general manager's duties, but with little success. In May 1915, C. M. Christenson became manager of the Hackley, Phelps, Bonnell Company. Transportation and equipment advancements were implemented, and in September 1928, Christenson bought out the company's assets.

The Phelps sawmill operated until 1957, when the cost of manual labor made it financially obsolete.

The town experienced a spurt of growth between 1908 and 1912, when the Finnish moved to the area and began farming. In clearing the land, the Finns produced many cords of chemical wood for the plant. Finns left their mark in the area, in the form of many fine barns and saunas, which attest to their artistic abilities and wood craftsmanship.

In reality, it has been recreation, not timber, that has been the economic backbone of Phelps. The Twin Lake Hunting and Fishing Club was formed in the 1880's, and later became the Lakota Resort on North Twin Lake. The Louis Thomas Trading Post, established in the 1870's, has since become a recreation area. The Eagle River Rod and Gun Club originated in 1890, on Big Sand Lake, and today is the Big Sand Lake Club. The local Hazen's Resort on Long Lake opened for business in 1900. Sylvester Caskey also operated a resort during the early 1900's.

After C. M. Christenson's death, his son, Phil, took over the management of the property and land holdings. He has since developed the Smokey Lake Game Preserve, and today he owns and manages the Smokey Lake Realty Company in Phelps.

Today, the Town of Phelps is a lovely, small community located in the Nicolet National Forest on the northeast end of North Twin Lake. Some small industries still exist in the area, such as Sylvan Products, and the Four Seasons, a pre-cut summer home construction company. However, Phelps is still primarily a northern woods tourist center.

CAVOUR

The Forest County community of Cavour has a citizenry today of about 60, compared to its early population of about 600. Lumbering activities put the boom in town business in those days; in fact, one company took out 2 trainloads of logs each day, with the trains being made up of 40 or 50 cars.

The young town of Cavour boasted a general store, sawmill, hotel and saloon, all owned by Albert Hess. Business was brisk. For example, during one Sunday morning in 1917, Hess took in $600 across the bar in the hotel. That same year, the general store did $90,000 worth of business. Hess House was always crowded in those days, sometimes hosting as many as 100 people. Built in 1914, Hess House was in business for 23 years, until Cavour's population and popularity began to wane. Today, many of these early business structures stand empty.

|

| HESS HOUSE — 1965 |

Albert Hess came to Wisconsin with his parents in the boom days of 1903. He was a vigorous lumberman with firm ideas on conservation. In his heyday, Hess employed some 300 people and built 15 miles of his own railroad.

Local legend says Cavour was named for a "Count" Cavour, a timekeeper on the Soo Line Railroad, which first came through the area in 1887. But, it is more likely that the town was named for the Italian statesman, Count Camillo Benso di Cavous, whose diplomacy made him very popular in the United States a few years prior to the birth of this community.

TIPLER

The community of Tipler got its start when a small crew of sawmill hands came to Siding—83, thanks to the efforts of Arthur J. Tipler of Soperton, Wisconsin.

Tipler was a former mill superintendent with the Jones Lumber Company. William Grossman, an accountant and lumber salesman from Green Bay, became his partner in the summer of 1916 when they formed the Tipler-Grossman Lumber Company. A sawmill was erected on a site about 275 yards west of the railroad tracks, on an area now used for pulpwood stock piling. Portions of the concrete vault located in the mill office, along with concrete pillars from drying sheds, are still in evidence today.

The first lumber produced at the mill was used for the construction of a bunk house-boarding house complex for the single mill hands. Additional buildings were soon needed, and a horse barn, blacksmith shop, tool sheds and an office were constructed. The area south of the mill was cleared and "company" houses for the married men and their families were built. A half box car was used for the railway depot, and Adam Strom served as the depot agent. Following the construction of the depot, the town's name was changed to Tipler.

The Tipler-Grossman Lumber Company negotiated deals which enabled them to acquire vast tracts of virgin pine and hardwoods. In 1917, the company owned 39 sections of timber, and held purchase options on an additional 24 sections. These timber holdings ran for many miles in all directions. They reached into western Florence Township and eastern Long Lake Township, then west beyond Stevens Lake and south to the Pine River.

The first grocery and clothing store in Tipler was built by M. J. Dickenson in 1916. The building housed the store and post office, and stood just south of the company boarding house. In a small log cabin near the rear of the store lived Dr. Pintch, the town doctor. He provided limited medical service to the mill hands and their families for a one-dollar a month service charge.

In the housing area south of the store stood the first school house. It was a one-room, one-teacher frame structure. A fire caused by an overheated stove destroyed this building in the spring of 1922, forcing the school to move to a small movie theater at the north end of town. A modern, four-room brick school building was constructed in 1923.

The large building which today sits on the hill east of the tracks was built by Jess Gilmore in 1920. Gilmore operated a store and a very profitable moonshine whiskey business. He eventually sold his saloon and moved to Lakewood where he set up a fish-guiding business. In 1922, another grocery store was built by Lee Labelle of Laona, at the north end of town, south of where Mr. Earl's restaurant is today. A short distance north of LaBelle's store, a meat market was opened by Ed Kugel. Both businesses closed in 1929. Next to Kugel's store, there was a saloon run by Chris Boerger. From 1927 until 1938, Boerger did a profitable business in moonshine whiskey and home brew. After the prohibition was lifted in 1934, Boerger's saloon became a popular local meeting place.

Another grocery store was built at the north end of town by Lester Dickson. Smith's grocery now stands on the site. After two years, Dickson sold the store to Anna Tipler. She sweated out the Depression years, fighting bad credit risks and the County Welfare Department. Her son, Harvey, later took over the business which he operated for several years before selling it to an insurance company following a fire. In the jungle of business enterprises at the town's north end, Jim O'Connor operated another saloon and gambling establishment. After amassing a fortune, he sold out and moved to Florence.

The Tipler-Grossman mill closed for repairs and installation of more machinery in the summer of 1919. Upon the mill's reopening, the daily output of lumber exceeded 100,000 board feet per 10-hour shift.

|

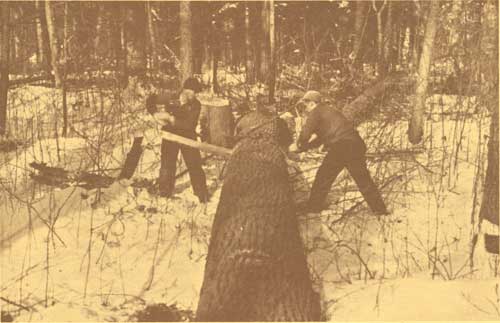

| EARLY LOGGING IN TIPLER AREA |

|

| HARVESTING THE "BIG ONES" |

As the sawmill operation expanded, the need for additional laborers was met by an influx of part-time farmers, lumberjacks and unemployed city dwellers. During 1919, a log house settlement of Kentuckians, from the foothills of Oklahoma and Kentucky, sprang up about four miles north of town.

In late 1928, the town's brightness began to dim, with the exhaustion of the timber supply. The mill owners tried desperately to negotiate for more timber holdings, but to no avail. The mill whistle sounded its last mournful blast in the fall of 1928. For many, it was the end of what had been a very profitable and comfortable life.

Many individuals left their mark on the Wisconsin northwoods. Here are a few Tipler citizens whose way of life left some lasting impressions:

A. J. Tipler — founder of the town and principal employer

William Grossman — Tipler's business partner

Bob Mazlein — mill superintendent

Carl Benninghaus — lumber yard foreman

Chris Peterson — railroad engineer

George "Peggy" Suring — part-time engineer on Tipler's railway and fireman

Merle Quimby — succeeded Mazlein as mill superintendent and was later appointed postmaster. Quimby also operated Dickson's store until the fire.

Adam Strom — first and only Tipler depot agent

Albert Schroder — barn boss

Charley O'Connor — company blacksmith and machinist

Lucille Kimball — school teacher

Otto Daumitz — town chairman in the early 1930's

Henry Henning — influential farmer

Herman LaBine — pioneer, farmer and woodsman

Lewis Smith — farmer and logger

Archie Shannon — local citizen

As evidenced by much of northern Wisconsin's frontier town history, lumber companies were often more than just places where people made a living. Rather, these companies gave life to the town, and as often, were the cause of its death.

At one time, many logging firms operated within the boundaries of today's Nicolet National Forest, including:

| Name of Company or Owner | Headquarters |

| Thunder Lake Lumber Company | Rhinelander |

| Holt Lumber Company | Oconto |

| Connor Lumber Company | Laona |

| Goodman Lumber Company | Goodman |

| Christensen Lumber Company | Phelps |

| Menominee Bay Shore Company | Soperton |

| Hiles Lumber Company | Hiles |

| Menasha Wooden Ware | Menasha |

| Oconto Company | Oconto |

| Minor Brothers (originally called Minor Town) | Carter |

| C. W. Jones Lumber Company | Wabeno |

| Flannery Steager Lumber Company | Blackwell |

| Siever Anderson | Mountain |

| Peter Lundquist | Mountain |

The Thunder Lake Lumber Company was organized and incorporated in Wisconsin on August 25, 1919. John D. Mylrea and his associates, Charles E. Lovett, J. O. Moen, and S. D. Sutliff, bought out the Robbins' Rhinelander sawmill and all their timber holdings. Originally, a contract was drawn up with the Robbins Railroad Company for use of the Narrow Gauge Railroad in transporting goods into the area. Thunder Lake Lumber Company eventually took over the railroad, and remodeled and rebuilt much of the main line for use in hauling sawlogs to their Boom Lake mill in Rhinelander.

The company established a new woods headquarters near Virgin Lake where the railroad grade crossed State Highway 32. Known as the Thunder Lake Store, it handled groceries, clothing, meat and other sundries. For many years, the store was managed by Roy Cunningham, who in later years became a Forest Service employee. A small community grew up near the store. Roy Cunningham, Ed Synnot, woods superintendent, Frank McClellan, shovel and steam loader operator, Pat Sullivan, timber cruiser, and several other people had their homes here.

|

| CAMP #14 — 1933 |

|

| STOCKPILED LOGS |

|

| A TRAINLOAD OF LOGS BEING HAULED ON THE NARROW GAUGE RAILROAD |

From the Thunder Lake Store, the company tracks were extended northeast around Lake Julia, east across the Pine River to within a few hundred feet of State Highway 55, north to the Butternut and Franklin Lake areas, and finally into the Brule Springs, Kentuck Lake and Spectacle Lake areas. This was hilly, rough country, requiring a lot of cut and fill before the tracks could be sloped low enough to permit travel by the railroad engines. A lima engine (geared drive wheels) was used to bring loaded log cars off the spur tracks to the main line.

The company completed most of the log cutting by 1940, with some scattered cutting through 1941. Following this, the track rails were pulled up, a job which was completed by mid-summer 1941. However, the Boom Lake mill near Rhinelander operated until 1943 on a stock of logs and a minimal amount of logs which were purchased.

The store at Virgin Lake was sold, and is still in operation as a grocery store. Mr. Mylrea's private railroad car, which was left sitting near the store was used for years as living quarters by Jack Bell, a former camp boss for the company, and his wife. The car and Railroad Engine No. 5 were later moved to the logging museum in Rhinelander, where they can still be seen.

THE LAND ABLAZE

Drought conditions stretched over many months, combined with hundreds of acres of slash that were left following the vast timber harvesting activities, turned Wisconsin's north woods into an explosive tinder box. Beginning in the late 1800's and continuing for more than half a century, forest fires were "Public Enemy #1."

One of the most devastating fires ever recorded in history was the Peshtigo Fire.

Peshtigo, Wisconsin, was a boom town during the logging era. There were numerous logging camps in operation nearby, and every spring large log drives jammed the Peshtigo River as the winter log cut was taken to market. In the northeastern corner of Wisconsin, the spring and summer of 1871 were dry and hot, with below normal amounts of precipitation.

Little or no concern for fire prevention, along with a prevailing attitude that there was more than enough forest lands to meet the Nation's needs, resulted in numerous wild fires being allowed to burn.

On Sunday, October 8, 1871, the area surrounding Peshtigo was hot, dry and windy. The air was filled with smoke from wild fires burning in nearby slashings and woodlands. Otherwise, life was routine — town residents went to church, while the lumberjacks nursed their hangovers from Saturday night. As nightfall approached, many of the town's people sat on their porches and watched the sun set in a red sky filled with smoke and bits of ash. As the evening wore on, groups of men were called out to try and stop a fire that was approaching the village limits. Their attempts were futile. It was evident that the village could not be saved; only then did the town's people realize that their lives were in danger. The fire roared into the village about midnight.

|

| THE PESHTIGO FIRE (left); MEMORIAL TO FIRE VICTIMS (right) |

Stories are told of people being burned to death in their homes, on the streets while trying to get others out of houses, and while fleeing to the river where many tried to take refuge from the flames. All in all, the fire burned an area of more than 1.25 million acres, and killed some 1,000 people — taking more human lives than any other single fire on record.

Communications were not very good in those days, and news of the fire and the destruction was slow in reaching the public. Also hindering reports of the Peshtigo blaze was the Chicago fire, which had occurred the same day, killing 300 people. Slowly, word reached Marinette and Green Bay. Help was sent to the village of Peshtigo; food and medical supplies were taken by wagon from Marinette and railroad from Green Bay.

Today, Peshtigo, Wisconsin, has a population of about 3,000. The area has been restored and sports beautiful scenery, giving the town a thriving tourist trade. A memorial marker has been erected where the temporary tent shelters were set up to house the survivors.

Poor land management practices and weather did as much to spur the Great Depression as bad business judgment. All across the Country, the land had been left defenseless against the natural scourages of water, wind and fire.

In 1931, near the community of Tipler, Wisconsin, the snow disappeared early in March. Hot, dry weather followed, creating a severe fire danger. Fire fighting tools and equipment were scarce in those days, thus many forest fires in the area were allowed to burn with little effort made to bring them under control.

Huge clouds of smoke covered the sun for weeks prior to April 18. On that day, 80 mile-per-hour winds blew in from the southwest, driving a widespread ball of fire before it. In its path was Tipler.

People ran in terror, leaving all their possessions behind. Company houses caught fire and exploded, scattering flames to other buildings. In less than three hours, the wild fire destroyed all but seven buildings in the community. For days, the people walked through the smoke and ashes of the burned-over village to view what they had once owned. The town of Tipler never fully recovered from this calamity.

|

| AFTER THE TIPLER FIRE |

One of the first cooperative Federal-State-local fire suppression efforts ever to take place within the Nicolet National Forest occurred in 1931 on the Hiles fire. The fire burned a large area, beginning near Hiles and running east across Highway 55. The blaze was fought largely by the State of Wisconsin, because the Forest Service did not have the equipment nor the organization. During Wisconsin's first fire protection period, the county covered one-half the costs, with the State picking up the remainder. However, on the Hiles fire, costs were divided equally between the Forest Service, State of Wisconsin, and the county.

The Hiles fire also marked the first time airplanes were used in fire suppression activities on the then young Nicolet National Forest. The Forest Service contracted a plane for one week to aid in scouting and suppression tactics.

By 1933, when fire threatened the town of Nelma, Wisconsin, the Civilian Conservation Corps was in full swing. CCC enrollees helped on this fire in the evacuation of Nelma residents, fire suppression and mop-up activities. The fire began May 10, and burned for nearly two months. The flames burned over 2,000 acres before being brought under control.

Fire continued to take its toll on the land, but with the establishment of the Nicolet National Forest in 1933, fire suppression became a number one concern.

|

| SOME OF THE BURNED AREA |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

9/nicolet/history/chap2.htm Last Updated: 08-Dec-2009 |