|

Taming Our Forests

|

|

INTRODUCTION

Our country is getting pretty full of people. There are about 127,000,000 of us now, and it is reasonably certain that by the end of the century there will be 150,000,000. Because there are so many of us and because we need so many more things to make us prosperous and comfortable than people have ever needed before, we must get more from the mines and the rivers and the soil—and much more from the forests.

|

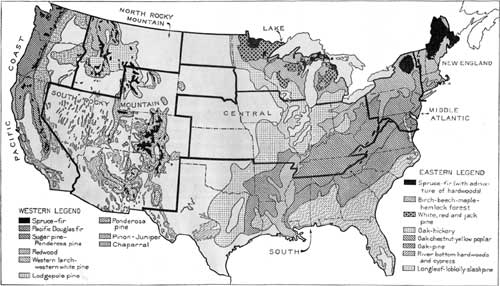

| One-third of our country is forest land. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Although one-third of our country is forest land—615,000,000 acres—we are not even getting as much wood from it as we use now; far less than we shall need when there are 150,000,000 of us. Already we are bringing it in from other countries.

Is that what we must do—import more and more wood as there are more and more of us?

Not if we tame our forests so that we will get better service from them, domesticate them as we have domesticated horses, wheat, cabbages, and hens.

We expect from our forests wood for such things as houses, railroad ties, paper, rayon, movie films, and fruits, nuts, game, and turpentine, as well as places in which to rest and play. We expect them to protect our land from erosion by wind and water and help us to control floods.

Trees cannot serve us in all these ways if most of their energy is spent in a struggle with each other for light and water and soil.

In the sort of community which a forest creates for itself one species of trees usually dominates the rest. These have fought their way up through a long merciless struggle of tree with tree, one kind against another, no quarter given the defeated. After the dominant trees have taught all the others their places, then there may come a sort of armistice, a truce, a pause in the conflict when the forest is said to have reached a climax. But, however serene a "climax forest" may appear, there is no more peace in it than in a boxer lightly poised to land the next blow. It is because this forest strife is so slow that men mistake it for peace. A fight between men can be finished in four rounds, but trees live so much longer than we do that they can afford to fight slowly. Their wars are like movies slowed up till they hardly seem to move, but they are in reality the savage conflicts of wild things. And the winners are not necessarily the ones we back—nor do they come through the struggle in the greatest numbers or in the best shape.

We want a forest to provide us with the special trees we need instead of those which may happen to grow there, just as we want a field to produce wheat instead of tumbleweed or goldenrod. To get a forest to give us the things we want is the same sort of a job as to convert a wild meadow into a cabbage patch. It is a matter of domesticating a wild thing—taming a forest.

How do we tame them?

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

taming-our-forests/intro.htm Last Updated: 19-Apr-2010 |