|

Taming Our Forests

|

|

WILD FORESTS

It is hard to realize when we see the beauty of a wild forest that we are looking at a battleground. Hard also to understand that the trees which compose it do not constitute anything like the best crop that it could give us, any more than the wild cherry trees in the New York State woods give a crop comparable, in terms of pies, with a cherry orchard.

Take for instance the trackless, uninhabitable forest in southern Florida. The red mangrove marching out into the sea in rows of columns 50 feet high protects it from the ocean. The tides gurgle up and seep back through the mangrove roots, which hold fast to the bottom. New seedlings drop among these roots; drifting things catch in them, mud and silt settle about them so that not only does the mangrove guard the coast, but it is continually forming new land. Back of the red mangrove with its fragrant leaves, the black mangrove, and the white, the protected land rises in what are called "hammocks" interspersed with sawgrass marshes. Upon the hammocks is a low wild jungle of tropical hardwoods. There is the gumbo limbo tree with a trunk of glistening copper bronze; the strangler fig, letting down a veil of heavy meshed lace, the floating gray banners of the moss, and through it all the perfume of perpetual bloom. The white ibis nests there and the roseate spoonbill and the sand-hill crane. The flamingo makes it a winter visit and the white egret and the great blue heron.

|

| Mangrove forest, Everglades. |

|

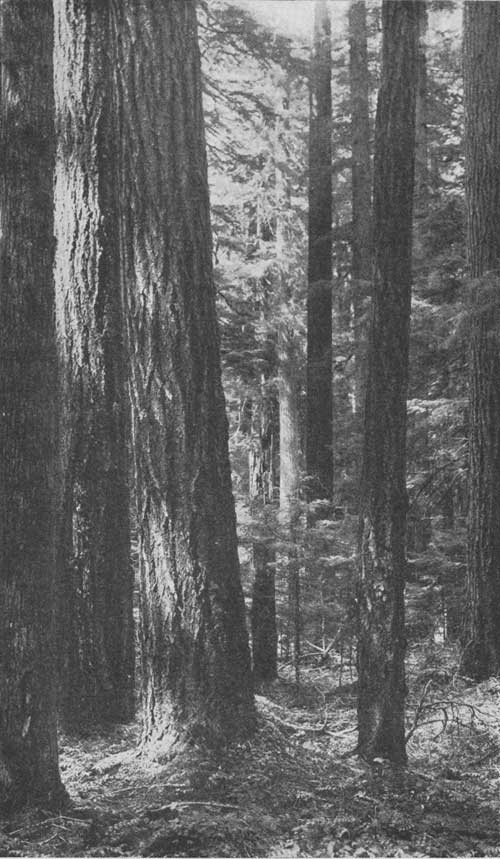

| Douglas fir forest. |

Pine grows there, and we perpetually need pine. But this is Caribbean pine, a poor wood. There is the mahogany tree. For 200 years we have considered the chairs and tables of its rich brown wood the most beautiful we could get. On the Florida hammocks the mahogany tree flourishes. Its leaves are green all the year round. In midsummer, it is covered with lilac-colored flowers. In December it hangs full of seed pods that look like turkeys' eggs. But the dark-red wood which we so prize does not come from this tree. No wood of great value grows in the Everglades.

This southern forest has grown to suit itself since the coral animal began to build up the Florida Keys, but it has little to give us except a beautiful picture and a laboratory for study.

If we start northwest from these wild tropical everglades at the tip of Florida, we will travel over the longest diagonal that can be drawn in the United States. First we cross through the yellow pine country in north Florida and in Alabama—a no man's land, raged over by man and by fire; then through northern Mississippi, where the water is stealing the soil from between the rows of cotton on the cut-over lands; on through Arkansas, where the bare sides of the Ozarks have been torn and gullied by the rains; over the Kansas prairie and the plains of Nebraska, where no trees have grown since the Rocky Mountains rose toward the sky; through the Wyoming pasture country; up into the forests of Idaho on the old Bridger Trail, which the covered wagons followed; across the "Inland Empire" with the Oregon Short Line; up over the Cascade Range and the Olympics; and down to the Washington coast, where an untamed forest of Douglas fir faces the Pacific as the mangroves of Florida face the Atlantic.

|

| Wild hardwood forest, Illinois. |

Early in April, when the growing time of the trees has begun, winds start to blow in from the Pacific. They have crossed the current of water which is warmed by the sun in the Tropics south of Japan before it flows up and across to our northwest coast, and they come to land heavy with drifting fog and soft warm rain. From April till late October they drench every needle of the trees, and fill the soil about their roots like a sponge. No bitter cold ever touches this land, nor heat, nor drought. It is as perfect a place to grow trees as the irrigated fields along the Rio Grande are to grow alfalfa. In this favorable climate—this perfect environment—the Douglas firs grow and grow. Next to the giant sequoias and the redwoods, they are the largest trees on the continent. Their huge straight trunks shoot up 100, 200, and 300 feet into the sky. The first branches are as far from the ground as a housetop. Below them grow other conifers: Western hemlock, Sitka spruce, silver fir—humble cousins of the great trees. There is a dense undergrowth of ferns as high as your shoulder, and the moist forest floor is littered with giant trunks rotting away.

This untamed forest is vast and dim and heavy with the scent of fragrant wood. It has a beauty that not even the white pines can equal. Six out of ten trees in it are Douglas firs, the trees most important to men of any that grow west of the Mississippi. And yet this wild forest is producing only about one-third of the timber it is capable of bearing. It is as though a fertile field grew only one stalk of corn to the hill.

If instead of going straight from Florida to Washington, we had turned north through Tennessee and Kentucky and crossed the Ohio River instead of the Mississippi, we would have come into the region of the central hardwoods—the broad-leaved trees.

Through whole geologic ages, that land has been preparing to grow trees. Long before the first ice age the plant tribes fought each other for it and left their records in the rocks. The land was warm and moist, and palms and figs won it for themselves. Then, for reasons that we do not know, the circle of ice around the North Pole grew wider year by year. It pushed down below the Arctic Circle, and the air that blew over the section became too cold and too dry for palms and figs. Magnolia, sequoia, sassafras, and gum, which could grow with less heat and rain crowded them out. But the ice sheets were coming on. They stretched themselves down over Canada, and in the wind that blew from them the magnolia, sequoia, sassafras, and gum were frozen, and spruce and balsam grew in their stead. Inch by inch, foot by foot, the ice came on. It swept over Minnesota and Wisconsin and down into Illinois. It covered the land, and all the trees died. It scraped them off and carried them away and left deep scratches in the rocks. How long the ice sheets overlaid the country no one knows, but about 400,000 years ago, they began to melt faster during the summers than they could freeze during the winters. Inch by inch, foot by foot, they went back to their own place, and the grass followed the retreating ice over the bare ground and made a great green prairie. But grass was not left long in possession of that land, for upon the slopes where their roots could hold better than those of the grass and beside the watercourses where extra moisture gave them an advantage, the trees came crowding in again. The elm pushed through the prairie grass, the hackberry, and the soft maple, and the oak, and the hickory; and following close after them, and towering far above them, came huge sycamores and tuliptrees; and later bur oak, ash, and hard maple, so that there grew up a new wild forest, not of conifers, but of broad-leaved trees.

In southern Illinois a piece of this forest has lasted from the ice age until now. Mammoths may have wandered through it, and the great grandfather of all the buffalo. The wolverine was there, and some of its close kin, and early man stole through it hunting for game that he could kill with a club.

The land has had thousands of years of preparation for the growing of trees, but on the territory this forest covers there is less than one great tuliptree, gum, or oak to the acre, and these are the trees we want. They stand out like Knights of the Round Table because they are so few.

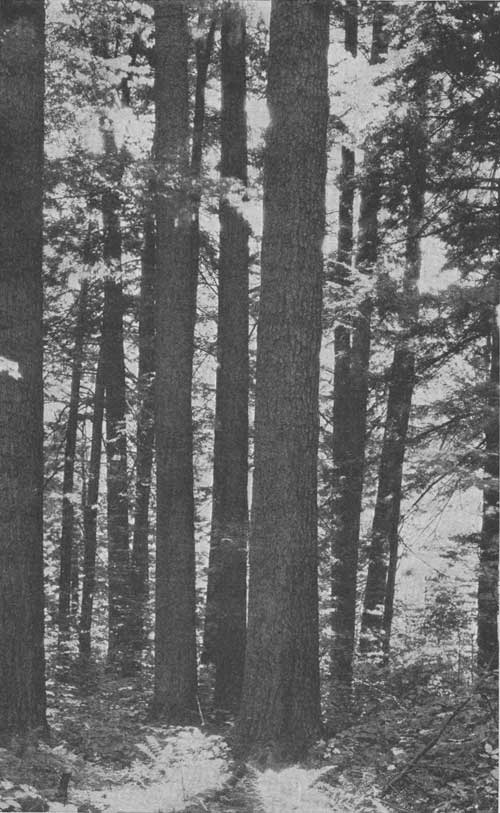

In northwestern Pennsylvania there is a wild forest called "Heart's Content." It covers a series of narrow valleys and steep hillsides broken by bare rocks. There are natural terraces and high among them clayey swamps, rock-covered wastes, and flood plains. It is a cool land with a wet wind blowing across from the Great Lakes from February until August, while the trees are growing. Then the wind swings farther to the south and sweeps up from Texas across the Mississippi and on through the valley of the Ohio. There is plenty of rain and during the winter there is nearly 6 feet of snow. It is a good place to grow trees.

About 250 years ago Heart's Content was swept by fire. Nobody now alive saw the fire. Nobody knows how it started. Nobody wrote about it. Nobody even told anybody about it. But a fire is the only cause for the situation which we find there now. All the trees on the hills were killed except a few young hemlocks which could resist the fire and a few old white pines that bore seed. It was probably a ground fire. We do not know what trees besides the hemlocks and white pines were in the forest. What we are sure about is the approximate date of that fire. We are sure of this because the age of a tree can be discovered by counting the rings that form around its center—one every year. Twenty rings mean that a tree is 20 years old. By counting the rings on white pines that have fallen at Hearts' Content, we find that most of them are 250 years old, and so we know that about 250 years ago a new pine forest was seeded from old trees now gone. Slowly they pushed through the underbrush that sprang up after the fire and shaded them from wind and sun. Very slowly they grew for 5 or 6 years, as white pines do. The young hardwoods—chiefly beech, yellow birch, black birch, maple, and chestnut, which began with them—grew much faster than the pines and gave them a light shade. But when they were 5 or 6 years old the young pines began to speed up. They distanced the hardwoods. They caught up with the hemlocks, which had had a century's start of them, and shot up 140 feet into the sunlight. Some of the young beech trees grew up along with them and helped to form a dense canopy of leaves through which almost no light could fall. Below the canopy of pines and beech, the older hemlocks formed a second roof, increasing the darkness below. The hardwood trees, birch, maple, and oak, which could find little to live on in the dim light of the forest, were left far behind in this slow race and formed a third canopy that deepened the shade still more. Far below on the forest floor was a cool, dark, damp place where the seeds of the white pine trees sprouted easily, but where they did not flourish. The final test of supremacy in a forest is whether a tree can bring up its young. There must be heirs to the throne. The young white pines die when they are tiny seedlings though the old trees have kept dropping seeds down from the forest canopy for 200 years.

|

| Hearts Content. |

Now, Heart's Content is a lovely thing, a scientific laboratory, a delight, and a comfort; but as a source of supply to man it is not satisfactory. Why? White pine is among our most useful trees, and in that wild forest it is being crowded out.

These wild forests, these wilderness areas which we are preserving, cover nearly 10,000,000 acres, and they give us pleasure and information—they are vastly important. But we can no more depend on wild forests like these to give us what we need in lumber than we can depend on wild antelopes to give us what we need in meat. Only from the forests which we tame can we expect a continuous supply that will help us to build a secure and increasing prosperity.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

taming-our-forests/sec1.htm Last Updated: 19-Apr-2010 |