|

Taming Our Forests

|

|

WHAT A TAMED FOREST IS LIKE

It is not easy to tame a forest that has had its own way for hundreds of years. Trees have habits and customs of their own. A wild forest takes no responsibility for furnishing a perpetual harvest of good, useful timber. What it has the habit of growing is an occasional giant leader and a tribe of inferior trees.

There is, up in the Chippewa Forest, in Minnesota, which is being tamed, one of these dominant trees, a vast white pine which towers above all its neighbors. The foresters say that it has stood there between 400 and 500 years. It is some 9 feet in diameter,and the roots slant out from the trunk like buttresses supporting a cathedral pier. The foresters have an affection for that tree.

"Hope you stay with us a long time, yet, Old Girl," said one of them, and laid a gentle hand on the bark.

|

| The "Wonderful Trail", Norway pine, Minnesota. |

For centuries that tree has been opening its brown cones and releasing pairs of winged seeds to the wind, in some years only a few of them, but every 5 or 6 years, seeds in a flying cloud. It has been the parent of many seedlings, but its descendants are not around it now. They must have sprouted, these seedlings, thick on the forest floor, hundreds and thousands of them as the years went by. Hundreds and thousands of them went to feed squirrels and birds; thousands rotted away; but other thousands lived and grew. They pushed up through the litter of needles and leaves and branches; they tried to get enough water and food and light to grow on. The weaker ones were starved to death, and the stronger ones grew on—fewer and fewer of them as time passed. Not so long ago the lumbermen came through that forest, cut out the younger generation of pines, and sent them to the sawmill. But for all the seeds the great old tree had scattered, it was plain that not many pine trees had lived to grow up, for there are not many white pine stumps within range of those flying seeds. There are signs of age on the great tree now; the buttresses are scarred and weak; there is rot at the root; when the winds sweep down from the north again it may fall before them; and there is not one white pine left to send out seeds in its stead. White pines, which are the most valuable trees that northern Minnesota can grow, could be springing up all through that forest now if it were treated like a garden bed, and the white pines given the first chance as the gardener gives the first chance to his young tomato plants.

|

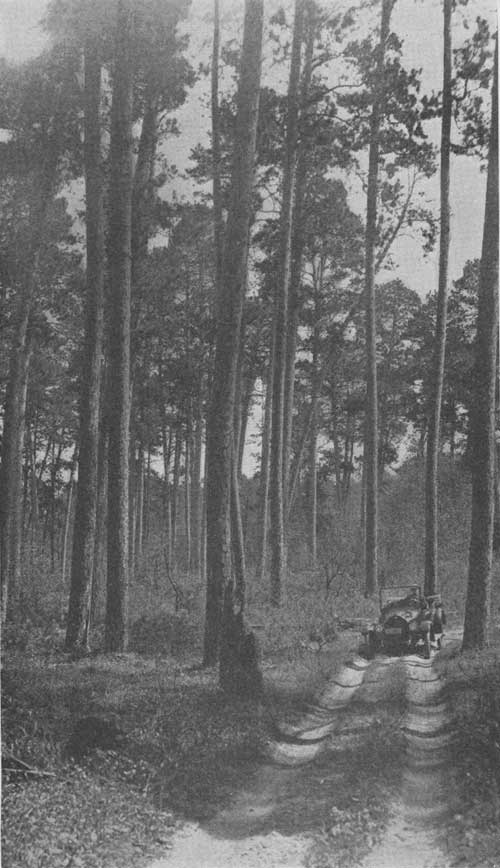

| Tamed forest, Cass Lake, Minn.—Norway pine. |

There is one of these tamed forests—a forest of Norway pine—not far from that old white pine. A few great trees stand above the others and sing in the wind. They must have sprung from seed that fell before any white man broke trail through that wood. Below them is a carefully thinned stand of their descendants about 50 years old—slender, straight, clean of branches for 20 feet, and swaying like seaweed in the faint violet light that is reflected from their colored trunks. They stand close together, for it is not the purpose of the forester to let them each have all the light they need without climbing far up to get it. They must crowd each other enough so that they will develop the tall straight trunks which give us the most valuable lumber. Farther down is a thick stand of 10-year-olds stretching their crowns toward the light. Close to the ground are the seedlings with a hundred years of growing ahead.

In these young forests which are being so carefully tamed there will be no great pine left without descendants. Barring fire, there will not have to be any replanting either, for the foresters know how to assist a forest in bringing up its young. A well-started, well-established, well-weeded, and well-cared-for forest can do its own replanting and furnish us with a perpetual crop.

So long as the seeds of the trees which we need do spring up and take root, so long as there is generation after generation growing up through the forest, so long as bare land is being covered with a new growth of useful trees which are not starved out by weed trees or crowded out by each other, we may leave the bringing up of the young forest to the old trees. Just so long and no longer! For we cannot permit a forest to exist for the production of a few giants. What we must train the forest to grow is a high average of board feet, year after year after year.

|

| Forest bringing up its young. |

No amateur can adequately break in a wild forest to the service of man. It is a job for a trained forester. First it is necessary for him to realize that forests are for the service of human beings, and to know what the 127,000,000 American people need that the forests can give them—whether it is boards and heavy timbers for railroad ties, or pulpwood, of which to make paper, or turpentine; or perhaps protection of the soil. Then he must know what sorts of trees will supply these special demands and whether the particular forest he is considering can be induced to produce them.

He must know the nature of the soil, how deep it is, and whether it contains the food that trees need, whether the winds will bring enough rain or whether there is an underground water supply—a good water table—to be counted on. He must go through that forest and see just how he can treat it so that the important trees will get all the room they need and all the soil and sunlight and water they can use. Are they close enough together so that they will grow tall and straight in their effort to reach the light, or are they so far apart that they grow wide and bushy like an apple tree in an orchard, with practically no tall trunks out of which long boards could be sawed? He must see how the seedlings are being brought up—whether there are enough trees of the sorts that enrich the soil such as birch and beech to keep them well fed and enough "nurse trees" to protect them till they are old enough to take care of themselves.

When he knows what he wants to get from that forest and what the chances are of his getting it, then the forester must begin to break it in to do the work. There are the trees that have reached maturity and are ready to be cut and sold—these must go. There are what are called "wolf trees"—trees that reach out to steal another tree's share of light—there are misshapen or diseased trees, or trees of worthless kinds that occupy space—these must go. There are places where so may trees of even the most valuable kind are trying to grow that they starve each other—these must be thinned, as a gardener thins out the extra carrots in a row. And that forest must be so regimented that there will be pushing up slowly layer by layer, generation after generation, trees for a perpetual harvest.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

taming-our-forests/sec2.htm Last Updated: 19-Apr-2010 |