|

Taming Our Forests

|

|

PLANTING A FOREST

With all the millions of acres which have been cut bare or burned bare with no old trees to seed them again and with our increasing population and our need of the things that forests can give, we cannot wait for the old slow ways by which forests cover the land. Seeds dropped directly to the ground do not go much farther than twice the height of the parent tree. Seeds flung out upon the rivers of wind may fall on stony ground or be picked up by the fowls of the air. This, the old and tried way of replanting a forest, is a conservative way, and if we had a million years or so, it would probably be a good way, but it is not a quick way nor a sure way. In view of the increasing number of things that 127,000,000 Americans need, and the number of acres which have lost their trees, we do not dare to wait for it.

The Forest Service is gathering seed of forest trees. To the Rhinelander Forest Nursery, for instance, where cone-bearing trees are started, bags and bags of newly gathered cones are brought. These are ripe but have not yet opened to let the seeds fall out. They are placed in shallow trays and slid into ovens where the heat is kept considerably above that of a hot summer day. These cones, prepared to hold a pair of winged seeds, close under each little pointed cover, against cold and drought and sleet and wind, perhaps for a season, perhaps for years, till the perfect warm, dry day comes to release them, find their long task miraculously shortened and the warm, dry day they were waiting for, unexpectedly arrived. Under this delusion, they raise their rows of shell-like covers and leave the seeds free. The trays of open cones are emptied into a great revolving drum and slowly tumbled round and round till the seeds are shaken out. Then a blast of warm air blows away their wings, as a threshing machine winnows the chaff from the wheat, and the pure seed is gathered up and kept dry and cool till planting time. Long before the usual time, the seeds of these conifers are ready to grow, and the length of time before a seed can become a tree is shortened by just that much. We do not dare to wait for deliberate nature unless we must.

|

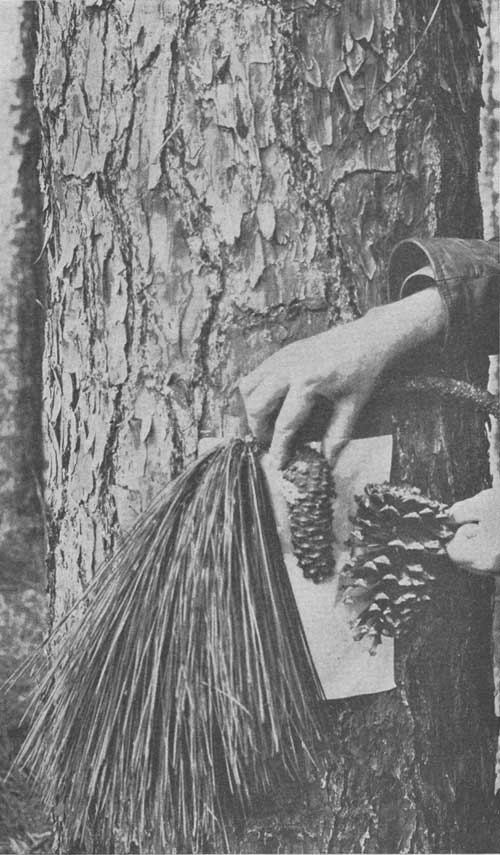

| Open and closed cones, Longleaf pine. |

The time is shortened also by the care given the seedlings. We do not let them sprout unprotected. As we entrust eggs to incubators instead of to the hen—sometimes 300,000 to a single machine—and as we do not rely on what bugs and worms an incompetent mother hen may chance to scratch up for her brood, but feed them scientifically to produce the biggest, healthiest chicks in the shortest time, so we take the ticklish business of bringing up a new forest away from the parent trees.

We send the seeds to the nursery, where they are laid in soil which has the perfect ingredients to give conifers a good start. Sometimes they are sowed broadcast and come up in a thick green carpet like a well-kept lawn; sometimes they are put in with a drill and grow in a pattern of narrow green stripes with earth between; but always they are planted in bands 5 or 6 feet wide and as long as there is room in the nursery. No hungry bird can peck them out of these green beds, no squirrel or chipmunk has a chance to get them, for over the top is spread a wire netting. When the sun is dangerously hot, there are wooden gratings to shade them, when there is danger of their drying out, there is an overhead sprinkling system like those installed to prevent fires in factories—long rows of pipes 5 or 6 feet above ground, with tiny holes through which drops artificial rain.

In these nurseries the little trees grow for 1 or 2 or even 3 years, as carefully guarded from injury as though they were the Dionne quintuplets. Sometimes they are transplanted from one seedbed to another, and the taproots that grow straight down are pruned so that the trees will develop strong side roots in their place; sometimes they are transplanted as a gardener takes out the snapdragons that have come up too thick—so that each young plant will have room enough to grow.

When the time comes for them to go out into the world, the reason for the planting in long narrow bands is clear. At the end of one of these strips appear two men with a knife blade as long as the nursery bed is wide. At the two ends it fits into a swinging frame which rests on skids one on each side of the band of trees. This machine is attached either to a gasoline motor, or to two horses. The long knife, like a straight scythe blade, is pushed down under the seedlings at the end of the row, and slowly pulled forward about 8 inches under ground. Above it there rises a green wave as the trees are cut loose from their seedbed and settle back upon it again. Down one long band of seedlings and up another goes this subterranean knife till as many trees are cut loose as are to be planted that day.

|

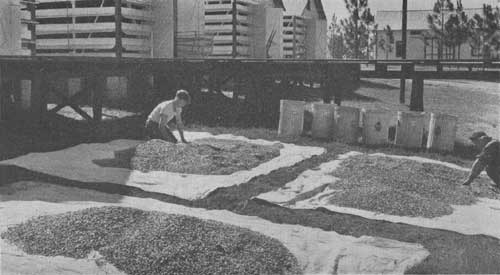

| Sorting tree seeds. |

Then comes a corps of forest workers—perhaps C. C. C. boys—who pick up the trees by handfuls; throw away all that have not grown as tall as they should, or have not developed good roots; and pack the others in long baskets—tops at the ends, roots in the center covered with wet moss. The trees are ready now to begin a forest of their own. The place is already prepared. If they are to go on rough ground covered with sod, the land has been "scalped", that is, the sod has been cut away and the soil left bare on 2-foot squares, 6 by 4 feet apart. If they are to be set on level ground it has been plowed in furrows 6 feet apart.

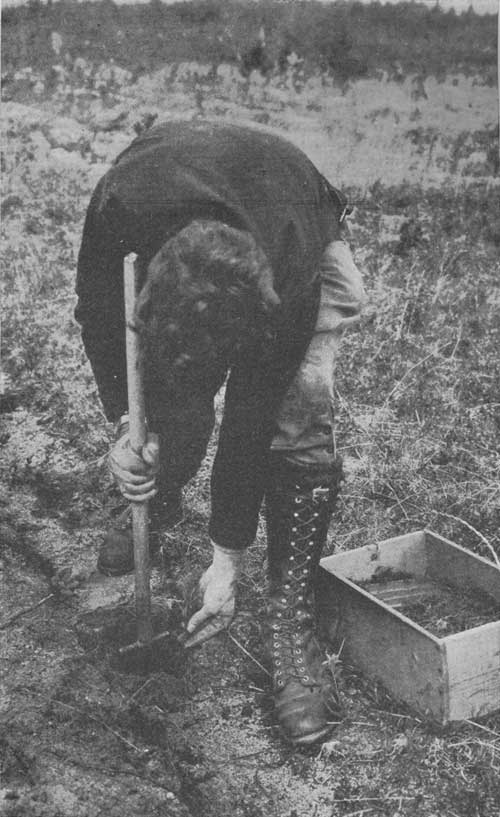

To the place for the new forest, the C. C. C. boys bring their baskets of seedlings. Each has a special planting tool in his right hand—a sort of glorified cross between a large sharp chisel and a small dull spade with a long steel handle—and in his left hand his basket of trees. They begin in a line, with the boss at one end, each boy back of the spot where he is to plant his first tree. The planting tool strikes deep into the center of the scalped square, the boy pulls it toward him, leaving a narrow wedge-shaped pit. He drops the planting tool, takes a tree from his basket and sets it in the place he has opened, pushes earth down around it and makes it firm with a foot on each side; then advances two paces to stoop and plant again, and the line of boys goes on across the land, leaving a new forest as they go.

Transplanting is in the nature of a surgical operation to trees, and sometimes they cannot survive it. All of them need time to get used to new conditions and prepare to meet new enemies. There are rabbits ready to nibble off the buds, there is beating sun, and drought, and wind, there are various insects lying in wait, and above all there are grass and weeds and brush and young trees of meaner sorts ready to crowd the seedlings out of their cleared spaces. Life is not easy for these young trees. Some of them die, but if neither fire nor disease attack them enough will live to make the new forest.

|

| The nursery. |

|

| Starting new forests. |

In a year, sometimes within 6 months, the workers come through again and free them from weeds. Where one tree has died, they plant another in its place. But they are careful not to destroy the quick-growing hardwoods—aspen, birch, scrub oak—which they find between the trees. These nurse trees can be counted on to protect the young forest through its most dangerous years.

Slowly the pines rise till the new buds are above reach of even the tallest snowshoe rabbit standing on the highest snowdrift. A time comes when the young pines no longer need the nurse trees—when they have become tall enough and strong enough to face wind and weather for themselves; then the forester goes through the young forest and sees that here the top of a pine tree is being injured by whipping against the trunk of a birch and there two pines grow where there is light for only one. There are trees that are bent and broken and trees that disease has attacked. There the hardwoods have made too thick a canopy of leaves, here some wolf tree is crowding the youngsters. The forester marks that forest for weeding, as a gardener would weed a tulip bed. The trees grow on and on—10 years; 15 years—till it is time for the first harvesting.

|

| C. C. C. planting time. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

taming-our-forests/sec6.htm Last Updated: 19-Apr-2010 |