|

Taming Our Forests

|

|

HARVESTING

Up to now young pines have been cut only because they were, for some reason, not good trees. But those which are cut in this first real harvesting are taken because they have grown fast and straight and are ready for use.

It is quite as important for the forester to know how and when to cut timber as it is to know how and when to plant it. Before a man with an ax, a forest is as helpless as before a fire. In getting out the trees, a logger can destroy the crop for 50 years to come. It is a far more difficult job than reaping a field of wheat.

To so cut the forests as to insure a perpetual harvest is an orderly scientific procedure. It is like the opening of a bridge game. It proceeds according to rules like a boxing match. It is like the operations in a smoothly running factory in which one process follows another in perfect sequence. This is the way it is carried on in the national forests.

When there is a sufficient number of mature trees in a strip of forest, trees which will pass into old age and decay if they are left standing, or trees which must be cut as thinnings, the forester in charge seeks a market for them. He sets the lowest price the Government will accept and advertises for bids. Each lumber company that is interested sends its representative to look at the trees and determine what his company is willing to pay for them.

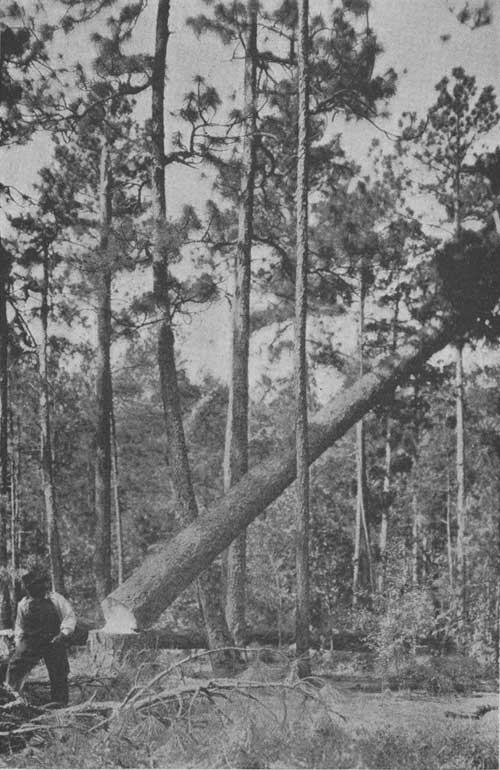

When the actual operation begins, the forester goes through and marks the trees which are to be cut and establishes rules for cutting. Logging crews of 35 or 40 men, if it is a large sale, do the actual felling of the trees. First a logger cuts out with the ax a triangle like a wedge of watermelon on the side of the tree toward which it is to fall. Then the men saw through from the opposite side a little above the apex of the ax cut. The tree falls toward the direction in which it has no support—where the wedge has been cut.

The forester must see to it that the trees are cut near the ground, so that as little of the tree will be wasted as possible.

|

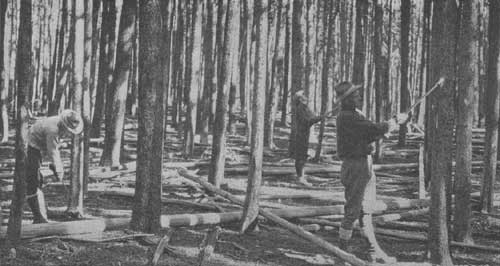

| Marking the forest for harvesting. |

|

| The tree goes down. |

|

| Log chute. |

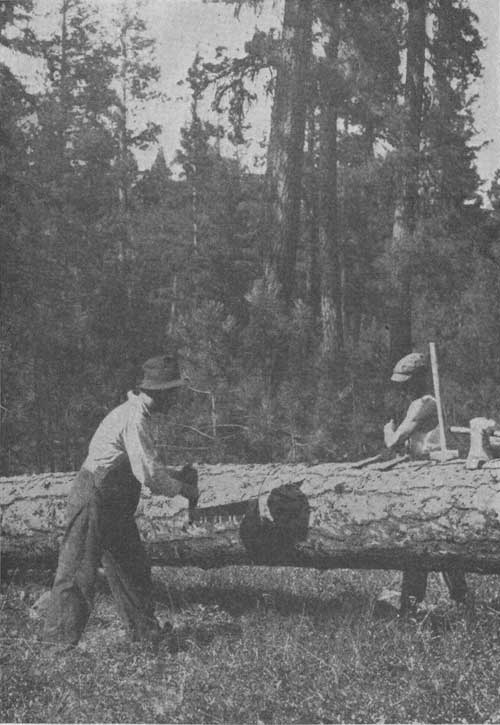

Then comes the bucker and saws off the top that is too small to be used in the mill, and the butt if it is rotten, and then bucks the tree into the required lengths. After him comes the skidder. The skidway, over which the logs are dragged out, must be cleared by whatever method will destroy as few trees as possible in the process. In some places—in the Northwest forests particularly—where the logs are to go downhill, instead of a skidway there is what is called a flume—a narrow trough the width of a tree trunk made of wood with the sides liberally greased—into which the logs are put, end to end, and slid to where they are to go, in a long swift wooden stream. Sometimes they are hauled out by steam; sometimes in the old way, by horses. Then they are loaded onto trucks or wagons or flat railroad cars or even onto sleds, which take them to the millpond, where it is easy to move them around and sort them before they go to the saws. Once the logs were floated down the rivers, but most of the good softwood trees near the riverbanks have been cut, and hardwood trees are usually too heavy to raft in this way.

|

| Yellow pine seed trees, New Mexico. |

To log without destruction is one of the things that the forester must understand because he must supervise it. If we are to have trees enough to satisfy our increasing needs, to log without destroying the forest is quite as necessary as it is to plant the cut-over lands.

After the first trees are gone, those that are left have a chance to expand and to shoot up farther and farther toward the light. It does not matter to them now whether the weed trees are thick below or deer browse on their tender branches. They are in control of their forest community, secure from attack from everything but wind, water, insects, disease, fire, and man.

And then comes a second harvesting, and perhaps a third, and finally a great cutting of all but those which are left for seed trees, so that the new young forest, which by this time is growing up below them, will have enough of light and moisture and food so that it can take the place of the old trees and the perpetual harvest can go on.

A forest like this is born tame, just as certainly as a canary bird that is hatched in a cage. There is no hard struggle for existence between the trees within it because the forester enforces peace. Each tree is allowed the space it needs to grow into what the forester has determined it shall be—not a giant grown great at the cost of the weaker trees around it—but one of a group sharing the light and food among themselves. It becomes a forest democracy instead of the oligarchy of the wild forest.

|

| Bucking the log. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

taming-our-forests/sec7.htm Last Updated: 19-Apr-2010 |