|

Taming Our Forests

|

|

DISEASE AND INSECTS

But what use to breed new types of trees that will shoot up at a speed never before known—what use to gather seed, and establish nurseries, and plant and prune if we do not protect forests from their enemies?

The forester must be a sort of doctor to the trees. He must understand what to do when they are sick. Disease in the forest is so common that until recently it has been taken as a matter of course. Most of the fungus diseases act slowly and their work is not evident to the casual observer, but the forester must learn to identify them in time. Other diseases spread swiftly. All the forester's efforts to produce vigorous trees in the shortest possible time, all his studies of their life processes and the factors of soil and climate and moisture, may go for nothing in the presence of such a thing as the chestnut blight which has practically eliminated the American chestnut.

Into a dining room in northern Minnesota came two anxious-eyed foresters. "How you getting on with the blister rust?", asked one.

"Bad! There's more of these currant bushes in my territory than there are rabbits—and that's some! It's hard to teach a new crew to know a currant bush after all the leaves are gone and harder yet to get all the roots up."

"Got to get them though!"

Yes, they've got to get them, for the fungus that destroys the precious white pines spends part of its life in a currant or gooseberry bush—its vacation time probably—and if there is no such bush within 900 feet of a white pine, then the tender blister rust spores die before they reach one, and the tree is safe. And so anxious men in high-laced boots appear before New England housewives:

"Madam, we're going over your land to get out the wild currant. It's to save the white pines."

Then there's the whish of busy poison sprays and a digging of roots, and sometimes a tearing down of old walls to get at obstinate shrubs—and an expert building of them up again.

|

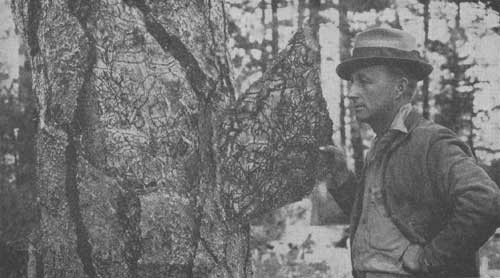

| What the pine beetle does, California. |

It must not be forgotten that insects also attack trees and find them good to eat—root, trunk, bark, and leaf. Hosts of these hungry pests are perpetually lying in wait.

And so the forester must learn about them! There are millions of insects that feed on different parts of living trees. Most of them do little harm, but occasionally a species sweeps like a scourge through the forest, killing thousands of trees. There is no use trying to destroy insects in the forest in any sort of individual, hand-to-hand combat. It is not possible to pick them off like potato bugs one by one. The forester must learn the life history of any enemy insect, must determine when and how to hit it, and then organize a campaign on a large scale to deal with it.

These campaigns do not always succeed. For years the forest service tried in vain to save the lodgepole pine in certain gulches of Montana. This is not a large tree, but it stands many to the acre, and timbers from it are used to shore up the great copper mines of Butte and Anaconda. The trunks of millions of them, hewn into ties, have formed the beds for the railroads that cross the northern Rockies. More than 95,000,000 new ties are needed every year. But the lodgepole pine has no defense against the subtle, well organized attack of a tiny beetle not a fifth of an inch long. A few beetle scouts fly ahead of the main body and take possession of a group of sheltered, well-placed trees. The next year hosts of their relatives move in. These beetles bore in between the bark and the wood and girdle the tree more effectively than could be done with an ax. A long, extraordinarily cold winter will freeze many of these beetles under the bark. If it is cold and wet at the time when the newly hatched beetles are ready to fly many are killed. But neither weather nor man has been able to win this fight.

In the Montezuma National Forest grows the ponderosa pine. This forest covers a broad high mesa in southwestern Colorado, and in 1910 a few Black Hills beetles were found there. The forest ranger reported that they need not cause serious alarm though they would "bear careful watching." During the following 20 years those beetles, having been watched but not fought, got a head start. Here and there they took possession of a few pines, bored under the bark and laid their eggs, and the trees died. By 1931 there were so many beetles in so many pines that the foresters tried to find a buyer who would cut down the infested trees and take them away. But this was 1931; the depression was on; there was no market for lumber; so the plan fell through. The next year the whole forest was honeycombed with the trees that the beetles had attacked. But there was still no market for lumber and no money to start the fight, so the Black Hills beetles kept on boring into the trees, laying their eggs, bringing up their offspring, and killing the ponderosa pines in peace.

|

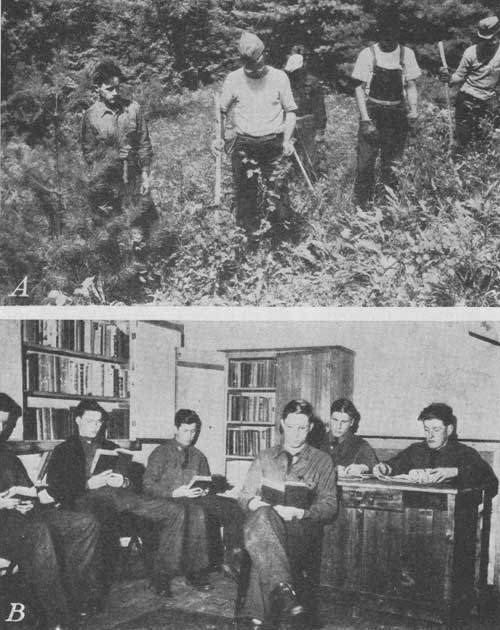

| (a) The blister rust crew. (b) C. C. C. school. |

But 1933 brought the C. C. C. Here were workers to fight that prolific beetle. Those husky young men cut down those infested trees and burned them or peeled the bark in which the eggs were hatching from the trunks and burned it, together with the limbs where the beetles lived before they were ready to fly. During 1933, 1934, and 1935 this fight went on. Occasionally the tide of battle turned against the trees, and there were more beetles; then it swung the other way, and there were fewer beetles and healthier trees. By the middle of June 1936, 20,084 trees had been cut, stripped, and the bark and the limbs burned, and the report came "The project appears to be completed."

Sometimes it is possible to fight one insect with another. There was, for example, the strange case of the ponderosa pine which was brought into Nebraska to help hold the shifting sand in place on the western hills. It was no sooner established than there appeared an insect called the Nantucket tip moth, which attacked it with disastrous results. This moth had made its slow way through the northern forests from the eastern island from which it took its name. Had the Nantucket tip moth an enemy? The scientists began to hunt for one. It was necessary to find an insect which would attack the larva of the tip moth at the moment when it was defenseless. Insects were imported from the four corners of the earth, but none were ready at the critical moment. At last there was brought in a wasplike insect from Virginia. The timing was perfect! The wasp killed the larva of the moth. But then a disconcerting thing developed. Another pine-destroying moth, which had been nearly starved out while there were plenty of Nantucket tip moths to feed upon the pines, now finding its way clear, fed itself full year after year, increased in numbers, and in its turn fell upon those ponderosa pines—and for the larva of that moth the wasp from Virginia had no appetite whatever!

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

taming-our-forests/sec8.htm Last Updated: 19-Apr-2010 |