|

Taming Our Forests

|

|

FIRE!

From the time that a tree begins its life the great, overwhelming danger it has to meet is fire. Fire will roast the seed in the ground, will suck up a sapling in one great whiff. The largest and tallest and strongest tree in the forest cannot save itself when fire comes through. All that the forests might do for our comfort and prosperity and pleasure can be prevented by this bright and dangerous foe.

|

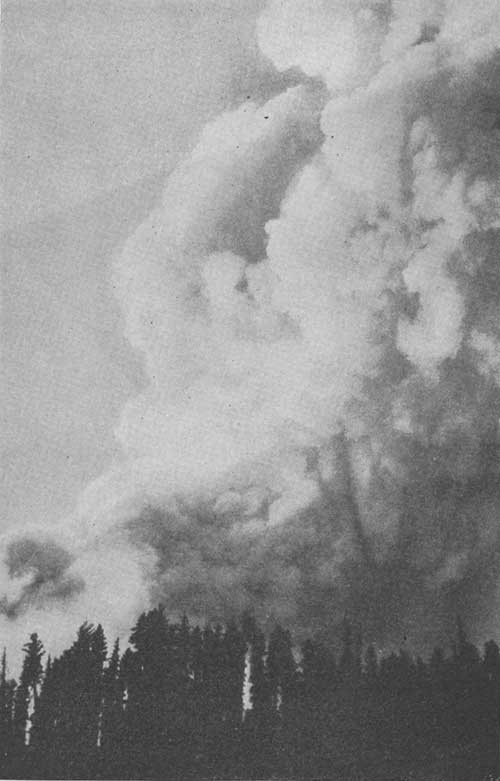

| Fire. |

What is this fire?

A simple chemical reaction, the satisfaction of one of those strange cravings between the atoms of which the universe is made, the result of the irresistible affinity of oxygen for other elements. When the temperature is high enough to change some other substance into a gas, the union is readily made.

A match, an electric spark, a stroke of lightning, two sticks rubbed together, flint striking steel, a dozen other things, will create heat enough to produce fire. And to put out a fire is to throw the process into reverse, either to get rid of the oxygen, get rid of the substances with which it unites, or to so reduce the temperature that a gas cannot form. A fire can be either frozen out or smothered. Both these methods are used in controlling forest fires. Sometimes the wood and brush and leaves are removed from the path of an oncoming fire so that the oxygen will have no other elements to unite with. Sometimes the fire is smothered by throwing earth upon it, which keeps out the oxygen, and keeps down the temperature. At other times it is put out with water. Water stays as water long enough to reduce the temperature below the level at which gas is formed. It has also what is called a high ratio of volume of vapor to the volume of liquid. That means that there will be a lot of steam from a small amount of water, and steam will keep out air and smother fire. Weight for weight, water has been found the best material to subdue forest fires.

There is no way of making forests immune to this chemical reaction. Wood will burn. What we can do is to keep fires from getting started; to so manage the forests that they will not be good fuel; to have the aid of science in keeping us warned as to when fires are likely to occur; and when they do start, to use every modern facility—human and mechanical—to put them out.

|

| (a) The start. (b) The finish. |

In the matter of prevention we must begin with ourselves. Fire is no invention of the human race. Before man learned to make fire, all there was came from the sky or the earth. If Thor launched his thunderbolts with a careful aim and they struck a tree, there might be fire. If he missed, there was none.

In the ranger stations are maps on which each fire is marked with a dot. These dots hang along the lines of the motor highways like beads. They are strung farther apart on the foot trails and the creeks where men fish. Sometimes there are no dots except on the roads over which men travel. Fire control is a poor substitute for fire prevention.

It is hard to alter habits. A cigarette butt is uninteresting. There is really nothing in a burned match to allure and charm, but the imperative need to break it in two and insert the charred end in a pocket instead of in a pile of dry leaves on the roadside, has got to be met. To gather sticks and build a fire beside a stream, boil a pot of coffee, and broil a strip of bacon has all the joys of Davy Crockett and Robinson Crusoe combined; but to dig down afterward and lay those burned sticks in a hole, to carry water from the nearest creek in the coffeepot and soak them past any disposition to smoke, to cover them hard and fast with earth that has nothing more inflammable in it than pulverized rock, and then to stamp on the place—these processes are as dull as brushing one's teeth. But to put out fires must become a human habit if we are to enjoy the gifts which the forest can offer us.

Through one of our inventions, the steam locomotive, we start almost as many fires as through that earlier invention, the match. We send these inventions roaring through the forests, throwing sparks into the air that fall to right and left of the track. Do we have to choose between our forests and our railroads? Not if we change them both.

To alter the locomotive is a relatively simple matter. Sparks do not have to fly out of locomotive stacks. They can be kept inside, and locomotives do not have to be run by wood, or coal, or even oil, or any fuel that will throw sparks. In many cases they can be driven much better, much faster, and, in the long run, much more economically, by electricity.

Then the forests can be made much less inflammable. Fires usually start in the underbrush and the litter. The underbrush and the litter can be taken away. Railroad fires usually start near the track. There can be a wide, clear space between it and the woods.

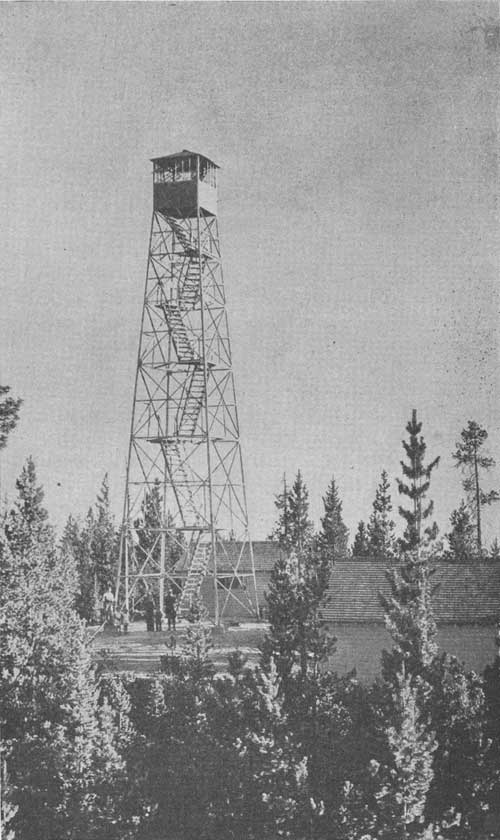

The first requirement for controlling a fire after it is once started, is to find it. This is not so easy as it seems. There are records of fires within the last 2 years which have not been located for more than a week, although men had seen their smoke in the sky and gone hunting for them through the woods. In order to find fires while they are still small, lookout towers are being built all through our forest country. These have an open iron frame work with stairs angling around inside or ladders going up the surface. When one is built on a high mountain top, it need not be very tall because the man in it doesn't need to be raised much from the ground in order to look across the sea of green trees below him. But when a tower is on level ground and the tall trees come close, then it must go up perhaps a hundred feet, so that the man inside can look over the top of the forest.

|

| Lookout tower. |

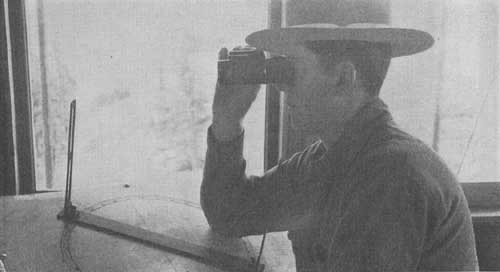

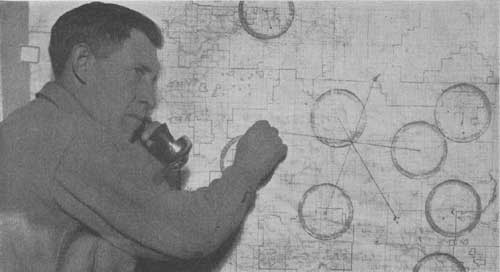

Up there in the singing wind he has a small room, glassed all around as though he were in a lighthouse. He has before him a map of the locality placed exactly like the country over which he is looking. As a captain finds the location of his ship with a quadrant, so the lookout locates a column of smoke by a movable bar on the map before him. The base of this bar is at the place where he is standing. He moves the far end of the bar until it points directly at the smoke, notes the position of the bar in degrees and the minutes and seconds of the same sort that are used at the observatory in Greenwich, and then telephones the direction to the nearest ranger station. Usually some other lookout in the vicinity has sighted the fire by now and telephoned in its location from his post. The ranger knows that where the air lines from two widely separated lookout towers cross is the place of the fire.

What happens after a fire is discovered and located is very different now from what it once was. The time when there was not much to do but pray for rain, particularly in the forest country of the West when the thunderheads came rolling over the mountains, is long past. It is very different from what it was only 25 years ago when the disastrous fire happened in the Coeur d'Alene National Forest in north Idaho.

Fires were raging in all directions and fire crews were fighting them 24 hours a day. It was mountainous mining country, and there were no roads over which motors could bring in fire fighters. They went in over the old trails either on foot or horseback. It might take them a day to reach a fire—or 3 days. There were no telephones except along the railroads.

|

| Sighting the fire. |

|

| Locating the fire. |

The forest supervisor sent E. C. Pulaski, a forest ranger and a great great-grandnephew of Pulaski, who with Kosciusko fought for American independence, from one fire to another to be sure that supplies were getting in. On the 20th of August, a terrific hurricane broke over the mountains—it almost lifted men from their saddles, it swept the mountains in circles. It picked up the scattered fires and joined them into a net of flame—and the men were inside it! Pulaski gathered up 45 panic-stricken men and made them take blankets and follow him through the raging, whipping fire. The one hope he had was to reach an abandoned mine tunnel he knew of. He gave his horse to an old man who could not keep up, and they raced for it. On the way, a frightened bear rushed along with them; a tree fell upon one of the men and killed him. But the others dashed into the mine mouth just as the fire swept over. Pulaski made the men lie face down in the tunnel while he hung blankets across the entrance and dashed them with water carried in his hat from a pool inside the mine. The timbers which held up the mine roof began to burn, and the men were in a panic—some cried; some prayed; one, crazed with fear, tried to rush out into the fire. Pulaski drew his gun and said, "I will shoot the first man who tries to leave." The soaked blankets at the mine mouth caught fire, and he put up more and carried water until his hands were blistered and, under the heat and gas and smoke, he sank unconscious.

|

| Fire at night. |

|

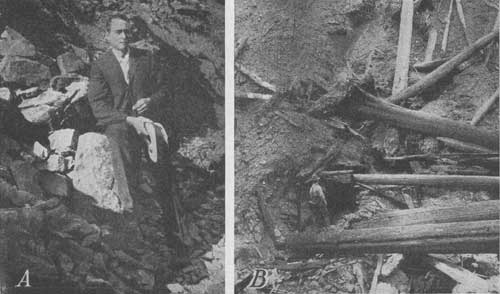

| (a) Pulaski. (b) The cave where the men took refuge. |

The first thing Pulaski knew was a man's voice saying, "Come outside, boys, the boss is dead." He felt fresh air draw into his lungs and heard himself answer, "Like hell he is!" Then some of the men who had revived before he did, dragged him outside. Back in the mine, five of them lay dead. At first those left alive could not stand, but as the fresh cool air blew over them, they got to their feet and started toward the headquarters at Wallace, over burning logs, through smoking debris; their shoes were burned off their feet; their scorched clothes were in rags. Pulaski's eyeballs were blistered; his world had gone black. One of the crew led him to a hospital, where he spent weeks recovering.

The forest-fire fighters of 1934 had many more things to help them than they did when Pulaski saved his men 25 years ago.

All the winter of 1934 there was hardly any snow on the mountains of central California. The spruce and pine could shake off the few light flakes that fell upon them from autumn till spring. The mountain streams that should have brimmed full till June showed a mere trickle when April was only half gone. If you rubbed a pinch of duff between your fingers it went to a brown powder so fine that it could drift off into the air. And the dry wind blew and blew and blew. The Plumas Forest was crisp and brittle. The sky was clear, the earth was dry, the wind was high and steady. May went by and June. In July the national forests were so dry that no one was allowed to enter without a special permit.

But August 17, with a dry wind blowing strong from the southwest, was a perfect day for a fisherman to escape from the city and climb 4,000 feet up in the mountains to try his luck along Nelson Creek. After his steep climb he would have been ready to rest, to make coffee, or perhaps light a pipe. Just what he did is not known, for the man has never been found.

Two lookout stations are within range of Nelson Creek. The first lookout reported rising smoke at exactly half past 12 and the second exactly 1 minute later. Just a minute after this, the dispatcher at the nearest forest headquarters telephoned the foreman of a C. C. C. crew of 40 men who were constructing a road, to call them together, furnish them with fire packs, load them into trucks, and start. In 23 minutes more they were on their way. Five miles by truck, 3 miles on foot, carrying their equipment, they reached the fire at 40 minutes past 2.

In the two hours and 10 minutes that fire, which had been no more than a veil of smoke blowing out above the trees when it was first seen, had gone raging up to the top of Eureka Ridge. Seven hundred and fifty acres of burning woods met those 40 men. But telephones in all directions had carried the call, and in 20 minutes 80 more fire fighters who had been rushed 18 miles by truck, arrived to reinforce them. At 5 o'clock came 240 more. There were now 360 men tearing out the underbrush, digging down to mineral soil, using bare rocky slopes and creek beds to establish a band around that fire, where the flames must die because there was nothing left to burn. Before sunset, another 100 men came in. There were now between 400 and 500 men working, and 1,500 acres were burning.

|

| Fighting the fire, California. |

During the night of August 17 the wind calmed down, and the air was cooler. Two fire lines had gone up the hill from the base beside Nelson Creek, one on each side of the burn. They had reached the top of the ridge. It looked as though the worst was over, and the foreman sent all but eighty of the freshest men back to camp to rest. Eighty men would be able to pull the ends of the fire line together, especially since a relay of 45 more, who had been working to eradicate blister rust, were on their way. They worked the rest of the night, and shortly after daylight the ends of the line were connected beyond the top of Eureka Ridge. The fire had now covered 1,950 acres.

At 11 o'clock the wind waked up again and whipped the smouldering fire into flame. It jumped the north line and burned a narrow strip up the mountainside. The first fire line had to be abandoned and a second line run up outside of it.

At half past 1 the heavy wind took the fire over the line at two new places on the south side where it had not had time to cool.

A patrol plane had come and was now flying back and forth. It brought the news that the fire had "lit-a-running," a quarter of a mile outside the line. By dark all the men were working on new fire lines. Three thousand one hundred and twenty acres had been burned.

During the next day 360 more men came in. Some of them were from a C. C. C. camp, others were S. E. R. A. crews, and another blister rust-control group had been gathered up. The first crew, which had been sent to rest, went on duty again in the middle of the night. By sunrise the fire was again corralled. Inside the line were 3,770 acres.

The northeastern section of the fire line did not hold; and the fire came down from the crowns of the trees upon a rough, precipitous cut-over country which led down to Peoria Creek. The men made a flank attack and tied a line around it.

But at the same time that the fire died down at this point, little whirlwinds west of Poplar Creek picked it up and carried it across the line for a mile and a quarter. By dark this new fire had covered 1,600 acres, and by morning 900 acres more had been burned.

Twelve short-wave radio sets were in use, some in camp, some on the line, others on high spots where there was a chance for the men to look ahead. A traveling Weather Bureau unit was set up, and every half hour it radioed forecasts of wind velocities to all the fire camps so that extra men could be sent to such dangerous areas as canyons and steep slopes or slash-covered ground.

Two hundred more men were brought in, but although they worked all night the fire was out of hand, and no lines could be drawn around it. Six thousand two hundred and seventy acres had been burned over.

The sun rose on August 20 on a terrible picture. The head of the fire was 8 miles wide. Before it was a heavy cover of slash and young growth. The strong wind carried sparks and lit spot fires half a mile ahead of the main blaze. The plane reported that some of these spot fires already covered 30 acres. The north and most of the south side were held between 19 miles of flanking line. During that day the fire force was increased to 1,100. The fire now began to back slowly down a hill on the north side where burning cones and branches rolled down across the fire lines into the forest below, but it was going so much more slowly that most of the men were sent around to the south and east sides, and that day they built 7 miles of new lines. But the fire flashed over again and again and before dark burned 950 acres more, and during the night 100 acres in addition.

August 21 was a day of high wind. The fire broke over the old flanking lines near the top of Eureka Ridge and picked up 200 acres more. The Weather Bureau reported the wind breaking into gusts, and 30 men who were sleeping were wakened and sent out to where the southeast line broke over in a series of small fires half a mile beyond the main line.

All during the night the crews were strengthening those lines which so far had held and drawing new lines around the spot fires that had started. By sun-up a line had been built in front of the head of the fire, and the men were trying to backfire, that is, to burn everything off a wide strip inside the line so that when the main sheet of flame came on it would die down for lack of fuel. But the wind was high; the main fire came on fast. The strip in front of it had not burned clean, so that a little after 1 o'clock the head of the fire carried over and burned another 1,350 acres. Again the men worked all night, and by morning on August 23 the fire was corralled inside a new line.

During the day of August 23, they had 29 miles of line under control so that men could be spared to go to the northeast of the fire where it had been alternately backing slowly downhill and then running rapidly up at a new angle. They tried to use a tractor on these lines, but the ground was too rough. Control lines were built around this by hand, but again and again the fire hurdled them, and during the afternoon it took 400 acres more.

On the 24th of August the fire jumped the line at only one point and took only 100 acres more. The wind was still strong, but the air was not so dry, and the moisture that was in it helped to control the fire.

For the next 6 days the wind was gentler, and not until the first of September did it jump a line again. Then there was a slop-over on Belle Bar Creek, but the fire picked up only 50 acres more. It had covered 10,150 acres.

After that there was the long job of mopping up. Where the crew saw smoke they pulled old stumps and branches apart so that they would not burn; they dug holes to bury clumps that could not be smothered by shovelfuls of earth. They stayed on the fire, patrolled it along the 29 miles of fire line and over the 10,150 acres which had been burned until heavy rains came in October.

Something over $50,000 in money that fire cost. But what did it cost in human comfort and prosperity and in the other things which $50,000 so poorly represent? How about the houses that can never be built now, the paper that cannot be made, the shining cloth that can never be woven, and the pleasure that hundreds of people might have taken in those 10,150 acres which are now stripped bare? Money has very little meaning set against the real cost of a forest fire.

|

| After the fire, Montana. |

The scenes of forest defeats are terrible places. There is no silence so terrifying as that in a burned-over forest. Living forests may be quiet, but they are full of gentle noises. The winds swing branches against each other, leaves fall, sleepy birds talk back and forth, squirrels rustle about. The desert has the perpetual murmur of soft shifting sands. Even a mile underground in a coal mine there are quiet whisperings as though the layers of rock were moving against each other. But in a burned forest there are no seeds to drop, not one ripe leaf breaks from its branch, not one branch is left for the wind to whistle through. It is a silence produced by a great death, and it will not be broken until life comes back.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

taming-our-forests/sec9.htm Last Updated: 19-Apr-2010 |