|

Aleutian Islands World War II National Monument Alaska |

|

Steve Hillebrand/USFWS photo | |

Unalaska ... Unangax ... Birthplace of Winds ... Cradle of Storms

Like precarious stepping stones, the Aleutian Islands span the seas between the New and Old Worlds—reaching westward from the Alaska Peninsula to within 500 miles of the Asian peninsula of Kamchatka. Situated between the Bering Sea and the Pacific Ocean, along the seam of the Pacific and American geologic plates, this 1,100 mile long archipelago has been, and continues to be, the locus of climatic and tectonic events.

Conflicting weather systems generated in the bordering seas are responsible for severe cyclonic storms, heavy rains, and dense, impenetrable fog. Yearly precipitation averages fifty inches with measurable rainfall occurring 200 days per annum. The Aleutian Chain's foundation of shifting geologic plates results in active volcanism and earthquakes—the birth processes of the islands themselves. The Aleutians betray their violent origins in their rugged landscape—in their mountainous terrain, precipitous coastline, and black sand beaches. It is thought that at least twenty-six of the Chain's fifty-seven volcanoes have erupted in the past two centuries. Yet, this dramatic environment supports the largest concentration of marine mammals in the world and a nesting seabird population greater than that found in the rest of the United States combined. The volcanist, Thomas Jagger, commented on the newest Aleutian Island in 1906—the still smoking Bogoslof: "The sea was full of fish, the beaches were full of sea lions, the hot lava and air were full of birds. Thus life and deadly volcanism lived together."

Such proliferation of wildlife drew man to the island chain as early as 8,000 years before present. By 4,000 years before present a great maritime nation had arisen, one adapted to efficiently exploit a single subsistence resource: the sea. From their skin boats, Aleut hunters harvested whales and pinnipeds—the sea lion, sea otter, and seal; sea birds were taken and their eggs collected; women fished for spawning salmon and scoured the rich intertidal zone for shellfish, seaweed, and driftwood. From the waters not only came their food, but the raw materials for the vast majority of their manufactured goods, garments, and tools. The sophisticated technology the Aleut developed to harvest the ocean was unparalleled; their ability to do so remarkable, considering their environment. In 1741, the Aleut, their island homeland, and the rich waters which constituted their livelihood were first seen by European eyes.

The Unangan

Within forty-five years after Russian contact, the native Unangan or Aleut, as the world at large has come to call them, generally estimated at twelve to fifteen thousand in number, plummeted to a few thousand persons at most—the population decimated by warfare, epidemics, and starvation. Exploited by Russian fur traders to harvest the sea otter, Aleut hunters were often enslaved, others forcibly relocated, some as far south as the Santa Catalina Islands off California; their wives and children held hostage to ensure acquiescence.

The Russian monarchy attempted to enforce fair treatment, but it was not until the arrival of the Russian Orthodox Church in the 1800s, that the Aleuts' rights were argued in Russian courts. After the purchase of Alaska by the United States in 1867, the Aleut found themselves classified as "Indians" and made wards of the government. Under U.S. protectorate, the Aleut entered a time of what can best be described as benign neglect, receiving little or no support from the Territorial or Federal authorities.

The Aleut worked the introduced fox and sheep farms for wages, became construction workers or longshoremen, but almost all still looked to the sea for sustenance. The Aleuts' hardships lasted for over two centuries, under the governing hand of two countries, culminating finally in the forced evacuation from their homeland during World War II, where the unique geography of their islands, the link between east and west, again played a pivotal role in their history.

To the early Aleut, the baidarka or iqax was a living being, the skeleton made of hewn driftwood covered with seal and sea lion skin, the joints bound with sinew, bone, and baleen. Craftsmen worked for a year or more on a single boat, fashioning an iqax both strong and supple, one that "bent" upon the wave. The finished iqax was made watertight with boiled seal oil, the skin shell often turning translucent as paper in the process, so that the hunter, the heart of the vessel, was visible within. In these superb craft, Aleut hunters could paddle for twelve to eighteen hours without rest, traveling 150 kilometers out to sea at speeds reaching eight miles an hour. They navigated by the stars and moon, by watching the winds and tide rips, the flight of birds and the direction of the ocean swell. The iqax was not only a sailing craft, but a hunting partner that identified itself with its master and wished to share his life. "Their fates, indeed, are bound up together;" states anthropologist J. Robert-Lamblin, "... their lives end at the same time; they disappear at sea together or, on land, share the same grave."

Spurred by Chinese demand for its luxuriant pelt, the sea otter was hunted to near extinction in 170 years of mostly unregulated hunting by European and American fur traders. Sea otter exploitation was finally halted by the United States in 1911, the otter population subsequently rebounding.

Other species were not so fortunate. The sea cow, a manatee-like creature, and the speckled cormorant both met with extinction during the Russian period. The Steller "sea monkey," a mysterious hybrid creature with a dog's head, drooping mustache and shark-like tail has never been seen again since its first sighting by Vitus Bering's crew in 1741.

Today, Aleutian waters are home to orca, humpback, pilot, and fin whales, to Steller sea lions, harbor seals, and Dall porpoise. The skies are profuse with birdlife—albatross and eagles, petrels, puffins, and jaegers, the rare whiskered auklet and ancient murrelet. The natural world remains sacrosanct to the Aleut, their sense of self deeply rooted in landscape and its wildlife. It is a place of intense beauty, charged with the ever changing colors of ocean and sky.

Unalaska's first Russian Orthodox church was constructed in 1808. In the 1820s and 1830s the church served as the seat of Father Ioann Veniaminov, later elected head of the Orthodox Church in Russia in 1868 and canonized Saint Innocent in 1977. Much of what is known of early Aleut culture and language is based on Veniaminov's observations.

Built in 1895, the present day Church of the Holy Ascension of Christ, is a National Historic Landmark. In 1996, the World Monuments Watch—a highly selective listing which includes India's Taj Mahal—designated the church's 250 religious icons one of the world's 100 most endangered sites.

The Russian Orthodox Church did much to alleviate the ills of colonization. Churches became the most prominent village structure and the locus of community life. Aleuts served as lay readers. They formed choirs, practicing the Orthodox liturgy in their own Aleut tongue. The Church became a sanctuary, its icons representing a spiritual world which transcended the often harsh realities of life. The Russian Orthodox faith remains a dominant force in modern Aleut culture.

In 1942, my wife and our four children were whipped away from our home ... all our possessions were left ... for mother nature to destroy ... I tried to pretend it really was a dream and this could not happen to me and my dear family.

—Bill Tcheripanoff, Sr., Akutan Aleut Evacuee

Some called the ordeal suffered by ... Aleut-Americans the "craziness of war," and dismissed that ugly portion of our history with that excuse. Not many of our people ... realized the ultimate insult of the entire story. The evacuations were not necessary; the Aleuts suffered for nothing.

—Agafon Krukoff, Jr., St Paul Aleut

Aleut Internment

In 1942, the Imperial Japanese naval base of Paramushiro lay only 650 miles southwest of Attu Island, the westernmost island in the Aleutian Chain. The Attuans, and the Aleutian Islanders in general, were wary of their proximity to the Japanese installation. "Some day they (will) come to Attu ..." predicted Attuan Michael Hodikoff. "They (will) come here; you see. They (will) take Attu some day." On June 7, 1942, in an event for the most part unknown outside of Alaska, Japanese forces did invade this small island, changing forever not only the lives of the forty-two Attuan villagers taken prisoners-of-war, but the Aleut people as a whole.

In response to Japanese aggression in the Aleutians, U.S. authorities evacuated 881 Aleuts from nine villages. They were herded from their homes onto cramped transport ships, most allowed only a single suitcase. Heartbroken, Atka villagers watched as U.S. servicemen set their homes and church afire so they would not fall into Japanese hands.

The Aleuts were transported to Southeast Alaska and there crowded into "duration villages": abandoned canneries, a herring saltery, and gold mine camp—rotting facilities with no plumbing, electricity, or toilets. The Aleuts lacked warm winter clothes, and camp food was poor, the water tainted. Accustomed to living in a world without trees, one open to the expansive sky, they suddenly found themselves crowded under the dense, shadowed canopy of the Southeast rainforest. For almost three years they would remain in these dark places, struggling to survive.

Illness of one form or another struck all the evacuees, but medical care was often nonexistent, and the authorities were dismissive of the Aleuts' complaints. Pneumonia and tuberculosis took the very young and the o d. Thirty-two died at the Funter Bay camp, seventeen at Killisnoo, twenty at Ward Lake, five at Burnett Inlet. With the death of the elders so, too, passed their knowledge of traditional Aleut ways. The death of the young foretold the demise of the future, but the Aleut people did not succumb. Attempts to keep Aleuts sequestered from nearby villages and towns failed. Evacuees found jobs. They built new living quarters in their compounds, repaired the old structures, and brought in electricity and running water. The villagers of Unalaska erected a makeshift church and named it after their beloved Church of the Holy Ascension of Christ. The religious articles and holy cards brought from the villages took on immense importance, the Aleut again turning to their faith for strength.

The Aleutian Campaign

Six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese aircraft struck at U.S. Army and Navy installations at Dutch Harbor in the North Pacific. Two days of aerial bombardment left over one hundred civilians and servicemen dead and wounded—their barracks, fuel tanks, and other structures set afire. The U.S.S. Northwestern, an aging Alaska Steamship Company vessel converted to a barracks ship, burned furiously in the harbor.

U.S. forces at Fort Mears met the first attack on June 3, 1942, with antiaircraft and small arms fire, but on June 4, eight P-40s, the Aleutian Tigers, rose to join the Japanese in aerial dogfights. The U.S. airplanes were launched from Cape Field, a secret airbase on neighboring Umnak Island. The Japanese had thought the nearest airfield was on Kodiak, and Cape Field at Fort Glenn, disguised as a cannery complex, had remained undetected. The surprise aerial counter-attack destroyed four Val dive bombers and one Zero.

In the following days, U.S. amphibious and bomber aircraft searched th Pacific Ocean for the Japanese carriers and their escort ships, with Zeros and the weather exacting a heavy toll on the search planes. Of six Catalinas that had come within sight of ghe fleet, four were downed by Japanese fighters, another claimed by the fog.

Notwithstanding the loss of life, the first forty-eight hours of the Aleutian Campaign exacted little substantive damage on U.S. or Japanese forces. The fort at Dutch Harbor was quickly repaired, and in spite of heroic efforts on the part of U.S. aircrews, no Japanese vessels were damaged. What had quickly become apparent to the combatants, however, was the role the capricious Aleutian weather would play in the campaign, acting as both ally and foe to both sides until the end of the war.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, had travelled extensively within the U.S. and was familiar with her industrial capabilities and seemingly limitless oil reserves. When the Admiral counseled against waging war with the "sleeping giant," he was met with veiled threats of assassination. "If you insist on my going ahead," he told the Prime Minister, "I can promise to give them hell for a year or a year and a half, but can guarantee nothing as to what will happen after that." The impetus for Yamamoto's attack on the Aleutian Islands was twofold: to divert forces of the U.S. Pacific Fleet from the central Pacific Theater and to gain a largely psychological foothold on American soil. He accomplished both goals with a minimal commitment of men and materials. U.S. and Canadian forces grew to 144,000 troops in the Alaska-Aleutian area by 1943, but the ships dispatched northward by U.S. Admiral Chester Nimitz from his fleet were but a token force having little or no impact on the outcome of the Battle of Midway. The Japanese occupation of Attu and Kiska is lands at the western tip of the Aleutian Chain, would in the end call for over 2,300 Ja panese soldiers of the North Sea Garrison to sacrifice their lives for the Imperial Edict.

Chronology of the Aleutian Campaign

| December 7, 1941 | Hostilities begin in the Pacific |

| March 31, 1942 | Runway completed at Fort Glenn |

| June 3, 1942 | Japanese attack Dutch Harbor |

| Jun 6, 1942 | Japanese forces occupy Kiska |

| August 30, 1942 | American forces occupy Adak |

| September 14, 1942 | Adak based U.S. aircraft bomb Kiska |

| January 12, 1943 | American forces occupy Amchitka |

| February 21, 1943 | Amchitka based U.S. aircraft bomb Kiska |

| May 11, 1943 | American forces land on Attu |

| May 29, 1943 | Last Japanese attack crushed on Attu |

| May 30, 1943 | Occupation of Attu completed |

| July 28 1943 | Japanese evacuate Kiska |

| August 15, 1943 | Allied forces occupy Kiska |

Battle of Attu

On May 11, 1943, two contingents of U.S. soldiers, numbering approximately 12,500 men in total, landed on the north and south ends of Attu Island and began pressing towards the Japanese strongholds at Holtz Bay and Chichagof Harbor. Progress was slow and costly. Eight days of heavy fighting passed before the South Landing Force climbed its way out of Massacre Bay. The North Landing Force, amongst their numbers the unorthodox Alaska Scouts, forced the Japanese from Holtz Bay, then continued towards Jarmin Pass and the North Landing Force to complete the pincer movement. The approximately 2,300 Japanese troops that remained had retreated to the wild heights of Fish Hook Ridge above Chichagof Valley, waiting for reinforcements. None arrived. On May 23, a force of sixteen Japanese Betty bombers was met by U.S. P-38 Lightnings over Attu. Five of the Japanese bombers were downed. It was the last attempt by the Japanese to support their Aleutian troops by air. On the ground, American forces had swelled to 15,000. Air striks and U.S. ground force assaults up the precipitous Fish Hook Ridge further whittled down Japanese forces. On May 29, Colonel Yamasaki, and the remainder of his Attu troops, numbering 750 or less, broke through American lines in a desperate attempt to reach Massacre Bay and needed stockpiles of U.S. supplies. They were finally halted at Engineer Hill, as a hastily organized U.S. defense repelled wave after wave of banzai attacks. Those Japanese troops that were not killed by U.S. fire, took their own lives. In the end, less than thirty soldiers of the North Sea Garrison were left alive, many ashamed that they had dishonored themselves by surrender. American dead numbered 549, with at least twice that number wounded.

Only 33 years of living and I am to die here. I have no regrets. Banzai to the Emperor. I am grateful that I could have kept peace of my soul ... Goodbye, Taeko, my beloved wife, Midaka who just became four years old will grow up unhinderd. I feel sorry for you Matsuko, born February of this year and never will see your father. Well, be good ... goodbye.

—Paul Nobu Tatsoguchi: final diary entry prior to his death on Attu battleground

The Japanese Occupation

The Eleventh Air Force alone dropped 26,910 bombs on Kiska and Attu islands in an attempt to soften Japanese emplacements prior to amphibious landings of U.S. and Canadian forces, but the Japanese troops were well entrenched, and the terrain was often obscured by fog. The boxy B-24 bore the brunt of the early missions, one of the few heavy bombers capable of making the 1,200 mile round-trip from Cape Field to the western end of the Aleutian Chain. Once over their targets, U.S. aircrews often had to drop their bomb loads blindly through the cloud cover, using the crests of volcanoes as landmarks, then fight their way home through antiaircraft fire.

Under their protective blanket of fog, the Japanese ground forces found the continuous bombardment little more than a nuisance. Construction of their own airfield on Kiska proceeded slowly for the Japanese, a lack of heavy equipment forced workers to use hand tools and wheelbarrows. With the departure of the carriers Ryujo and Junyo and their Zeros, the air defense of the islands rested on the Rufe float fighter plane. The U.S. Eleventh Air Force and the Aleutian weather took their toll on these fighters, leaving only a handful to meet Allied raids.

U.S. forces continued to move westward through the Chain. With the aid of heavy earth-moving equipment, engineers constructed a landing field in a water soaked tidewater flat on Adak Island in twelve short days. Just 250 air miles from Kiska, this forward field brought the Japanese within range of U.S. fighter and dive bomber planes. In the Pacific Ocean, American aircraft and submarines patrolled for Japanese shipping, effectively shutting off resupply and reinforcements. Isolated, their air power virtually eliminated, the Japanese troops dug in and prepared for the inevitable invasion.

Escape from Kiska

After the expulsion of the Japanese from Attu, U.S. naval and aerial bombardment of Kiska increased in fervor. Japanese submarines attempted to evacuate the estimated 5,100 Japanese troops on the island, but the process proved too slow, and far too dangerous with a tightened U.S. blockade. On July 28, under the cover of thick fog, Japanese cruisers and destroyers managed to slip through U.S. naval forces and aerial reconnaissance without detection. In thirty minutes, the 5,100 Kiska troops were boarded, and the fleet headed back to the safety of Paramushiro Harbor. The evacuation was so bold and well executed, U.S. commanders refused to believe it had taken place. However, U.S. fighters strafing Kiska no longer received return antiaircraft fire. In one instance, four U.S. P-40s landed on the shell pocked Kiska airfield. The pilots left their planes and strolled near the runway, seeing no sign of the enemy. In spite of this evidence, U. S. intelligence argued that the Japanese adherence to the Bushido Code forbade them from surrendering Kiska without a fight. The lessons of Attu, America's first experience with Japanese suicide attacks, had been too well learned. The invasion of Kiska went underway as planned. On August 15, 1943, U.S. and Canadian troops landed on Kiska. In the three day operation that ensued, over 313 allied soldiers died from "friendly fire," booby traps, and mines.

The Japanese had occupied U.S. territory for over a year before being routed at Attu. Not since the War of 1812 had a foreign battle been fought on American soil. Weather claimed more than its share of lives. Soldiers shot their own in the fog; ships were thrown against rocks and sunk; pilots met the sides of mountains in heavy overcast skies, or flew off into the void never to be seen again.

Aleut Restitution

Despite their poor treatment at the hands of the U.S. government, the Aleut remained a fiercely patriotic people. Twenty-five Aleut men joined the armed forces. Three took part in the U.S. invasion of Attu Island, and all were awarded the Bronze Star. At their camps, the Aleut surreptitiously voted in Territorial elections. Through exposure to the outside world, they had come to understand the importance of their participation in the democracy by which they were governed, and they desired participation with the full rights of citizens.

The Attuans suffered the severest deprivation during the war. For three years, they were imprisoned in the Japanese city of Otaru on Hokkaido Island, subsisting almost soley on rice. Sixteen would die there. On the day of their release, the survivors left their quarters through the windows, a symbol of their newly acquired freedom, bringing with them the cremated remains of the dead to be buried according to Russian Orthodox custom in their beloved Aleutians. But there would be no return to the village of Attu for its people, nor for the people of Biorka, Kashega, or Makushin. Partly due to financial considerations, U.S. authorities had decided these villages would be incorporated into the villages of Unalaska, Atka, and Nikolski. What the war had not done, a stroke of the pen had accomplished—four communities had met with extinction. Those villagers allowed to reoccupy their homes found them ravaged by the weather and vandalized by U.S. servicemen, the windows smashed, doors and furniture gone. Worse still was the theft of religious icons and subsistence equipment—boats and rifles. Some Aleut worked until their hands bled to repair the damage that had been done, but it would take years to recover, to fashion new communities and a new order for themselves. Politicized by their stay in the camps, the Aleut began the long battle for restitution. The evacuation had taken place for humanitarian reasons, but racism too had played a role in their abrupt evacuation and poor treatment in the camps. It would be forty years until restitution would be made, but on August 10, 1988, Public Law 100-383 was signed calling for financial compensation and an apology from Congress and the President in behalf of the American people. Throughout their recorded history, the Aleut were thought to be a people on the verge of extinction, but like the sea otter, whom the early Aleut believed to have been transformed human beings, the Aleut have proven their tenacity and ability to adapt. Survival against overwhelming odds is their personal victory.

Based upon "When the Wind Was a River" by Dean Kohlhoff

Aleutian Islands World War II National Monument

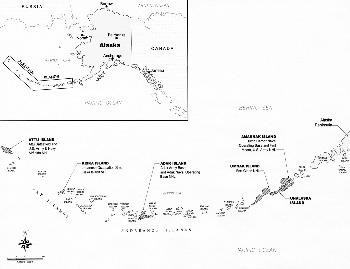

(click for larger map) |

World War II forever changed the Aleutians, the Unangax people, and the lives of those who waged battle there. Key battlefield areas of Attu and Kiska, along with a portion of Atka Island, are part of the Aleutian Islands WWII National Monument.

During World War II the Aleutian Islands became a fiercely contested battleground in the Pacific. This thousand-mile-long archipelago saw invasion by Japanese forces, the occupation of two islands; a mass relocation of Unangax civilians; a 15-month air war; and one of the deadliest battles in the Pacific Theater.

All sites in the Aleutian Islands World War II National Monument are on lands managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. These sites became part of the refuge in 1913 when President William H. Taft established the Aleutian Islands Reservation (Executive Order 1733) as a breeding ground for native birds, propagation of reindeer and furbearers, and encouragement and development of fisheries.

Various parts of the Aleutian Islands WWII National Monument have additional designations. Some of the lands are located in the Aleutian Islands Wilderness (designated in ANILCA) and overlap with two National Historic Landmarks ― the Attu Battlefield and U.S. Army and Navy Airfields on Attu and the Japanese Occupation Site on Kiska.

In 2008 sites in Alaska, Hawaii, and California WWII were re-designated as World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument in by President George W. Bush.

The John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management and Recreation Act (formerly known as the Natural Resources Management Act) was signed into law on March 12, 2019, making the Aleutian Islands WWII National Memorial its own stand-alone unit, separate from the previously incorporated sites in Hawaii and California under the name WWII Valor in the Pacific National Monument.

Source: NPS Brochure (Date Unknown) / USF&WS Website (May 2023)

|

Establishment Aleutian Islands World War II National Monument — March 12, 2019 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL WEBSITE |

Documents

Aleutian Voices: Vol. 1 No. 1 (2014) • Vol. 2 No. 1 (2015)

Attu Boy (Nick Golodoff, 2nd. rev. ed., 2012)

Attu: The Forgotten Battle (John Haile Cloe, 2017)

Cultural Resources of the Aleutian Region, Volume I Occasional Papers No. 6 (Gary C. Stein, October 1977)

Cultural Resources of the Aleutian Region, Volume II (Gary C. Stein, October 1977)

Enabling Legislation: Aleutian Islands World War II National Monument, Alaska (Public Law 116-9, John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation Management and Recreation Act, March 12, 2019)

"Everything changed!" — the ramification of the Second World War on the Canadian North (©Raynald Harvey Lemelin, Michael S. Beaulieu and David Ratz, extract from Journal of Tourism Futures, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2020)

Lost Villages of the Eastern Aleutians: Biorka, Kashega, Makushin (Ray Hudson and Rachel Mason, 2014)

Silent Sentinels: The Japanese Guns of the Kiska WWII Battlefield (Dirk HR Spennemann, 2014)

The Battle of Attu - 60 Years Later (undated)

The Cultural Landscape of the World War II Battlefield of Kiska, Aleutian Islands (Dirk HR Spennemann, August 2011)

View to the Past: A Driving Guide for World War II Buildings and Structures on Amaknak and Unalaska Islands (Jacobs Engineering Group Inc., U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Alaska District, April 2003)

World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska (Charles M. Mobley, 2012)

World War II in Alaska: A Resource Guide for Teachers and Students (2013)

World War II in the Aleutians (Linda Cook, June 1991)

World War II National Historic Landmarks: The Aleutian Campaign (undated)

aleutian-islands-world-war-ii/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025