|

War in the Pacific

War in the Pacific National Historic Park An Administrative History |

|

Chapter 3:

AMERICA ON GUAM — 1898-1950

Introduction

The presence of a foreign sovereign was not new to residents of Guam, but the role of colonizer was certainly new to the United States. The Treaty of Paris, ending the Spanish-American War, stipulated that Spain would free Cuba, withdraw from the Philippines (whose future would be determined later), and cede to the United States Puerto Rico and other islands in the West Indies, along with the island of Guam. During the next fifty years the island served as an American naval colony. Guam's residents assimilated a new set of customs and habits while it continued to play an important geopolitical role in support of imperial interests in the western Pacific.

The morning of June 20, 1898, Spanish Governor of Guam Juan Marina learned with great astonishment that four unidentified foreign vessels were steaming passed Hagatna on their way to Apra Harbor. One of the four was a warship. Marina soon found out that these were hostile American ships, and that the United States had been at war with Spain (in the Spanish-American War) for two months, since April 25. The four American vessels had come to capture Guam on their way to the battlefront in Manila, Philippines. The year 1898 marked a dramatic, abrupt end to nearly four hundred years of Spanish contact and influence. The next fifty years witnessed the dominance of America on Guam. As an American naval colony between 1898 and 1950, Guam's residents assimilated a new set of customs and habits even while remaining peripheral to American development of the island. Guam also continued to play an important geopolitical role in support of imperial interests in the western Pacific.

U.S. Initiation as Colonialists

Guam had nothing to do with the causes of the Spanish-American War, a conflict that marked a great turning point in the history of the western Pacific and the United States. In the 1880s and 1890s, the United States turned away from its anti-imperialist tradition, dominant after Civil War years (1860-1865), and emerged as an ambitious, aggressive, even covetous nation. A strong sense of national mission to bring civil liberty and Christianity to other cultures and to open markets for American trade around the world merged with the influential voices of a few foreign polity elite in the national government to fuel the growing popular belief that the United States had a manifest destiny to fulfill as a major power. In the 1890s, a series of imperialist outbursts brought the United States to the brink of war with Germany over a dispute involving Samoa (in 1889 and 1890); encouraged the annexation of Hawaii after a rebellion of local Americans against the Hawaiian queen (in 1893); prompted serious discussions of war with Italy and Chile over miner crises; and threatened Great Britain with war over a controversy in Venezuela (in 1895). The U.S. also teetered on the brink of war with Spain over American aid to rebels resisting Spanish rule in Cuba (in 1896). Influential naval strategist and author of The Influence of Sea Power Upon History (1890) Alfred Thayer Mahan believed that the United States could only become a great powerful nation if it extended its sea power beyond North America to strategic locations in the Pacific and Caribbean. [49]

In a frenzy of national excitement instigated by the New York Journal's sensational headlines, "The Whole Country Thrills with War Fever," accompanied by a front-page story about a terrific mysterious explosion that sunk the American armored cruiser Maine in Havana Harbor, Cuba, on February 15, 1898, heightened the nationalist urges of America's imperialist foreign policy elite, including then Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt. Newspapers around the country shouted for revenge over the loss of the Maine and its 250 officers and crew. In April 1898, Congress declared Cuba free from Spanish rule, demanded that Spain withdraw from Cuba, and directed the use of armed force to achieve these ends. With this declaration of war on Spain, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt sent Commodore George Dewey to Manila Bay, where, on May 1, he defeated the aged Spanish fleet in seven hours.

United States Marines soon left San Francisco on the cruiser USS Charleston to assist Dewey with the capture of Manila. After being joined by three troop transports in Honolulu, fifty-four-year-old navy Captain Henry Glass put the four-ship convoy to sea. As soon as he was clear of land, he opened his sealed orders from the secretary of the Navy and learned that his immediate destination was not Manila. Instead, he had been ordered to capture Guam and to imprison the Spanish governor, other government officials, and any armed forces–all in a day or two–before continuing on to Manila. Guam, argued the U.S. Naval War Board, was an important coaling station and its capture would help support the campaign in the Philippines. [50]

Early on the morning of June 20, 1898, the Charleston entered Apra Harbor in dense tropical squalls. With no prior knowledge of the war between Spain and the United States, the shocked Spanish Governor Juan Marina was asked to surrender the defenses of the island. He and military officers were all taken prisoners of war. On June 21, 1898, Captain Glass had the American flag raised at Fort Santa Cruz on Apra Harbor; and a twenty-one-gun salute was fired as military bands boomed the "Star Spangled Banner." The next morning, Captain Glass's convoy left Apra for Manila, leaving no United States' officers or enlisted men behind to oversee activities on the U.S.'s new imperial possession. On August 12, the Spanish-American War ended just three months after it had begun.

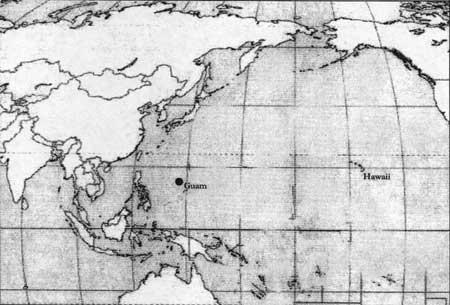

The Treaty of Paris, signed by the United States and Spain on December 10, 1898, (and ratified on April 11, 1899) stipulated that Spain would free Cuba, leave the Philippines (whose future would be determined later), and cede to the United States Puerto Rico and other islands in the West Indies, along with the island of Guam. The rationale presented at the peace conference for giving Guam to the United States focused primarily on the concept of Guam as a stepping stone in the Pacific, between Hawaii and the Philippines. Guam, it was argued, was a convenient stopping place and useful as a coaling station in an era when naval ships were fueled with coal. (American expansionism in the 1880s and early 1890s was explicitly aimed towards obtaining naval coaling stations in places like Samoa, Midway, and Guam in the Pacific. The Treaty of Paris further specified that Congress would determine the civil rights and political status of Guam's inhabitants. The local residents were never consulted on this matter. The Treaty of Paris made the United States a major colonial power in the Pacific. [51]

A fourteen-month period of confusion prevailed between the departure of Spanish Governor Juan Marina and the arrival of the first U.S. naval governor. In December 1898, President William McKinley had issued Executive Order 108-A, which placed Guam under the control of the United States Navy. In 1899, the entire island of Guam was designated a naval station. In reality, the U.S. Navy acquired all Spanish crown lands when Guam came under American rule, which amounted to roughly one-quarter of the 214-square-mile island. For the next forty-two years, all of the American governors of Guam were naval officers, who were serving at the same time as the naval station commandant. [52]

On August 7, 1899, Captain Richard Phillips Leary, chosen by the secretary of the navy as the first U.S. governor of Guam, arrived in Hagatna with instructions to fulfill the mission of the U.S. by maintaining the "strong arm of authority, to repress disturbance, and to overcome all obstacles to the bestowal of the blessings of good government upon the people of the Island of Guam." [53] Captain Richard Leary's interpretation of this mandate became, in part, embodied in a series of orders and proclamations he issued during the next year. Reflecting the rather stern, Victorian tendencies of the historical era and his own outlook, Leary immediately proclaimed that all activities related to church and state must be separated and that Guam residents must submit to the new American authority. He then issued executive general orders to prohibit the sale of liquor and its importation without a license. Leary also ordered that all land sales be halted until a new land registry system was established. In an attempt to do away with certain existing cultural practices, Leary prohibited celebrations and processions in Chamorro villages, on patron-saint feast days, he sent many Catholic priests away from Guam, and he declared unlawful the common practice of couples co-habitating and raising children together outside marriage. In addition, Leary issued proclamations and executive orders that: abolished peonage; [54] implemented agricultural and labor reforms; revised the land tax system; and established a new tariff for imports. Governor Captain Leary also instituted a public health program with navy doctors and corpsmen providing free medical treatment to the island residents, and he set up a public education system under naval control, with instruction in English, which replaced the Spanish Catholic church school system. [55]

Finally, Governor Leary ordered the completion of several public works. The U.S. Marines made improvements to the governor's residence (including the installation of typhoon shutters and the first corrugated tin roof on the island), cleaned up the main plaza in Hagatna for a military parade ground, repaired roads and bridges, dug sewers, improved water drainage and distillation systems, and constructed the first water storage tanks on Guam. Leary also instituted garbage collection, required outhouses in the main villages, and installed the first telephone system in Hagatna and Piti. When Captain Richard Leary and Lieutenant William Edwin Safford stepped down from their posts in mid-July 1900 and left Guam after only one year's residence, the cultural landscape, especially in and around Hagatna and Piti, had changed noticeably. The refurbished governor's residence, roads, bridges, tidier streets, water tanks, and outhouses collectively began to convey the physical image of United States occupation and the extension of the "strong arm of naval authority" over America's first colonial conquest. [56]

American Commander Seaton Schroeder relieved Captain Leary as governor and as naval station commandant on July 19, 1900; Ensign A. W. Pressey took Safford's place as lieutenant governor. Unlike Leary, Governor Schroeder spoke Spanish as well as French and seemed more accepting of the Spanish cultural traditions that had become integrated into the daily lives of island residents. Schroeder immediately reversed Leary's interpretation of the separation of church and state and once again permitted patron-saints feast days celebrations in the villages. Within a few months, the new governor allowed Catholic priests, sent away by Leary, to return to Guam.

The charitable and humanitarian volunteer efforts of Maria Schroeder, the commandant's wife, continued to improve public health conditions among residents. Maria Schroeder raised funds in the United States to build a new hospital. Although the native residents were suspicious at first, they eventually agreed to subject themselves to new foreign medical procedures. Common afflictions (ring worms, hook worms, and tape worms) began to be treated. The mortality rate of local residents began to drop. When Governor Schroeder conducted the first American census in August 1901, he learned there was a total of 9,676 non-Americans on Guam: 9,630 "citizens" of Guam and 32 mostly Spanish "aliens." Schroeder's census showed that the population of Guam had increased nearly twenty percent since 1886, when the last official count of residents had been made. [57]

During Schroeder's command, the Guam residents became increasingly restless and dissatisfied with the United States Navy's rule of the island, described by islanders as a "military government of occupation." Residents presented a petition to Schroeder, stating that "fewer permanent guarantees of liberty and property rights exist now than under Spanish domain" and asking that a special commission be sent from Washington, D.C. to study and recommend ways to create a permanent civilian government on Guam. Schroeder endorsed the petition. This effort marked the first in a long series of proposals that sought civil liberties and representative government for Guam residents.

In the early 1900s and for the next fifty years, the United States Navy rejected each and every such proposal. In 1901, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the navy's absolute authority over Guam in a series of cases, collectively known as the Insular Cases, holding that the U.S. Constitution does not apply to insular territories (also called "flag territories" or "possessions)." In the key case, Downes v. Bidwell, Justice Henry B. Brown captured the racist view especially prevalent at the turn of the nineteenth century. In his opinion: "if these possessions are inhabited by alien races, differing from us in religion, customs, laws, methods of taxation and modes of thoughts, the administration of government and justice, according to Anglo-Saxon principles, may for a time be impossible." [59] Justice Edward D. White concurred with Brown and made a distinction between "incorporated" and "unincorporated" U.S. territories. Guam, designated an "unincorporated" territory, according to Justice White, was not intended to become a U.S. state and, thus, should not be treated as an integral part of the United States. As a result of the Insular Cases, in 1904, the U.S. attorney general informed the secretary of the navy that "the political status of these islands is anomalous. Neither the Constitution nor the laws of the United States have been extended to them." [60] By the end of Governor Schroeder's two-and-one-half-year tenure, the structure and legal basis for U.S. naval authority on Guam had been firmly established. [61] The island was to be administered as a ship, "the 'USS Guam,' the governor as captain, U.S. military personnel as crew, and the Chamorro as mess attendants. [62]

Ordered Tranquility

Over the next fifteen years, U.S. naval governors (or acting governors/ commandants) came and went on Guam. Between 1903 and 1918, fourteen men served in this dual position for an average tenure of just over one year. These American governors, although often hardworking and capable, rarely became knowledgeable about local conditions and the Guam residents. Although considered more socially benevolent, the American administration of Guam differed little from that of the previous Spanish military rule, except for the separation of religious and governmental affairs and the imposition of the English language. Life for Americans on Guam settled into a placid colonial tedium of a small tropical outpost.

Each American naval officer serving as governor of Guam pursued a slightly different administrative agenda. Commander William E. Sewell (February 6, 1903-January 11, 1904) formalized Guam's judicial system and procedures. Commander George L. Dyer (May 16, 1904-November 2, 1905) initiated a detailed cadastral survey of the island and its waters, which was worked on sporadically over several years (and still incomplete by the early 1990s). Dyer also expanded the Maria Schroeder Hospital, and created a local civil service for islanders. Captain Edward J. Dorn (December 28, 1907-November 5, 1910) stressed the Americanization of Guam during his gubernatorial tenure by instituting the official observance of U.S. federal holidays, eliminating all but U.S. currency on the island, initiating the first island newspaper, the Guam News Letter, in May 1909 in both English and Spanish, and by creating the island's first public prosecutor, known as "Island Attorney." Captain Robert E. Coontz (April 30, 1912-September 23, 1913) energetically, although unsuccessfully, pushed Congress for the military fortification of Guam. Commander Alfred W. Hinds and the Navy Department invited American business firms, such as Atkins, Kroll & Company of San Francisco, to import and export goods to and from Guam. Captain William J. Maxwell, governor from March 28, 1914 to May 30, 1916, created the first local retirement fund for the Guam civil service. In 1914, he also attempted to gain citizenship for the people of Guam, however, was rebuffed by the Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt. [63]

During this same fifteen years, the lives of island residents improved in some respects, even though civil liberties and equality under the law were withheld from the island residents. Health care provided to Chamorro by naval doctors and dentists helped improve residents' quality of life by eradicating certain diseases (such as gangosa, a form of tertiary yaws) and aiding in the treatment of still deadly measles and whooping cough. Public education expanded, and students received free periodic medical exams. Chamorro enjoyed certain new amenities on the island, including electric lights in downtown Hagatna, a few paved roads, and the recreational diversion of baseball, all the rage in the United States. Nothing, however, substantially changed laws, practices, and attitudes that relegated Chamorro society to unequal status as inferior, second-class members of American society on Guam. The so-called "Jim Crow laws" in the United States that affirmed racial segregation in schools, housing, and nearly every aspect of social and civil life in the early 1900s, permeated American-dominated Chamorro society. Racial inequality was especially virulent in navy hiring and wage scales, where one rate existed for American citizens and a much lower one for Chamorro. During the early 1900s, the United States Navy did not permit the enlistment of Chamorro men except as mess attendants. [64]

|

| Figure 3-1. Guam Naval Militia parading in Agana. Photograph dates from the 1920s or 1930s. Courtesy of Gordon S. Chappell. |

Although political and social conditions remained much the same on Guam during U.S. naval administration between 1903 and 1918, the world around Guam and the island's place in it changed dramatically. At first, seemingly small but increasingly larger events drew Guam into a new global reality. The completion of the first undersea commercial telegraph cable linking Guam, Manila, Midway, Honolulu, and San Francisco in 1903, followed by the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914 brought Guam into a direct avenue of modern communication and transportation linking the island with the rest of the world. Guam began to be seen as a vital stepping stone in the Pacific–a secure way station and a relay point–in the communication and transportation channel between the West Coast of the United States and the Philippines. [65]

Neutrality Broken by World War I

Increasingly, during the early period of U.S. administration, the navy began to appreciate Guam's militarily strategic geographic location and relationship with the islands and resources scattered around Micronesia. Japan had been interested and active in the South Sea Islands since the 1880s. Both Japan and Germany had commercial interests in the western Pacific; Guam was at the geopolitical center of these overlapping spheres of interest. Early on, the United States took measures to protect Guam's harbors and provisioning capabilities against potentially unfriendly countries with commercial interests around the Pacific, particularly in Asia. As early as 1906, the U.S. Navy began to formulate a series of secret contingency war plans, each one known as "War Plan Orange," that cast Japan (orange) as the enemy in a future war. The initial and subsequent revised War Plans Orange emphasized the importance of defending the Philippines, Guam, and Hawaii with combined U.S. Army and Navy forces. When war broke out in Europe in early August 1914 and Japan declared war on Germany two weeks later, the United States assumed a passive stance as Japan seized control of all German Micronesia (including the Northern Mariana, Caroline, and Marshall islands). [66]

As the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungry, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire) fought tenaciously against the Allies (Great Britain, France, Russian, Italy, and Japan) in the Great War (renamed World War I after the Second World War began), the United States remained uninvolved militarily. Guam's status as an oasis of neutrality in the western Pacific did not prevent it from engaging in certain wartime activities. For example, War Plan Orange was revised twice between 1914 and 1917, a detailed plan of the defense of Guam was completed in 1915, new artillery was placed on Orote Peninsula, and an "Insular Force" consisting of Chamorro men was formed to assist navy personnel at the port. In March 1917, Governor Captain Roy C. Smith decreed universal, unpaid military service for all Chamorro men between the age of sixteen and twenty-three. United States neutrality in the mid-1910s, did not keep Guam detached from the war and the complexities of wartime activities in the western Pacific. Guam businesses sold over two million pounds of copra [67] to Japan annually, after war had increased the demand for coconut oil. [68] Additionally, the United State manufactured and exported munitions and goods of all kinds to the Allies for the war effort, and America loaned the Allies money to buy those goods. By 1917, the United States had loaned the Allies about $2.2 billion; the Central Powers had received far less from the U.S., about $30 million.

On December 14, 1914, the German navy cruiser S.M.S. Cormoran, with its 373-man crew, entered Apra Harbor seeking a re-supply of coal. Guam Governor William J. Maxwell, Captain of the U.S. Navy, interned the ship in harbor, where it remained for two years. On April 7, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany, shortly after German U-boats attacked American ships and the U.S. learned that Germany was trying to persuade Mexico to attack the United States. When Guam Governor Captain Roy C. Smith sent two officers to demand surrender of the Cormoran and the request was evaded, a U.S. Marine Corporal Michael B. Chockie fired a shot across the bow of the Cormoran's supply launch in an attempt to stop the fleeing launch. Chockie's shot was the first one fired by an American in the Great War–later known as "World War I." Only minutes later, the commander of the Cormoran blew up the ship to keep it from being seized by the American Navy and he and his men swam toward shore. The Cormoran remains at the bottom of Apra Harbor, 120 feet down. [69]

Ordered tranquility characterized life on Guam after the dramatic scuttling of the Cormoran. The U.S. Navy on Guam had no further involvement in the Great War other than installing two 400-hundred-foot-high towers on Libugon Hill for a high-powered radio station. The cultural and social life of the Chamorro remained unaffected by the war. Local customs continued to mix Chamorro and Spanish traditions. The Chamorro language continued to be the dominant language on Guam, even after two decades of U.S. occupation. Land and family lineage continued to be, as always, the basis of wealth and prestige in the subtle caste system that existed in Chamorro society. Natural disasters not wartime activities interrupted this tranquility in 1918. A mammoth typhoon slammed into Guam in July, severing miles of telephone and electric wires and, from late October to December that year, a devastating influenza pandemic, which raged worldwide, swept across Guam, leaving 858 dead (nearly 6 percent of the population). In the midst of the world's struggle against this deadly disease, World War I ended without fanfare or public celebration with the signing of the armistice on November 11, 1918. [70]

Life After War

After the war ended, life on Guam followed a predictable pattern similar to the first two decades under United States administration; each governor and naval base commandant exercised hia own particular style of administration and set of priorities that influenced the lives of Guam residents in subtle and sometimes profound ways. The autocratic, racist Captain William W. Gilmer (November 15, 1918-July 7, 1920) issued over fifty rigid orders in less than two years, ranging from edicts against whistling and the fandango dance in public to prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages, barring interracial marriages, and instituting the death penalty for serious crimes. Life on the island was humorless and grim until the U.S. Navy relieved Gilmer and replaced him with an intelligent, fun-loving man, Captain Ivan C. Wettengel (July 7, 1920-October 28, 1921). Wettengel immediately rescinded some of Gilmer's most outrageous orders. Acting Governor Captain Adelbert Althouse (February 7, 1922-August 4, 1923), favored the continued acculturation of Guam residents to American ways through education. He reorganized the Guam public school system, patterning it after the California system, and encouraged the organization of a new monthly, the Guam Recorder, which, over the next two decades, featured many articles, English language publication, on the history of Guam by Lieutenant Commander P. J. Searles. [71]

Commander Willis W. Bradley, Jr., who served as Guam's governor from June 11, 1929 to May 15, 1931, was militarily accomplished (graduated first in his class at Annapolis Naval Academy and received the congressional Medal of Honor in World War I) and a civil libertarian. He made a greater impact on local political conditions than any American governor before him. Soon after arriving on Guam, he recommended that U.S. citizenship be granted by federal legislation to all native residents; he immediately followed up by issuing his own proclamation that established Guam citizenship and naturalization procedures. Bradley also recommended that Guam citizens be granted a bill of rights, protecting them from any arbitrary and capricious decrees ordered by future naval governors. He also established the "Second Guam Congress" (purely advisory, like the First Guam Congress), consisting of two legislative houses (Assembly and Council), and he implemented the election of village commissioners. Finally, Willis Bradley initiated ambitious efforts to improve Guam's decrepit roads, overcrowded schools, construct all new public buildings of concrete, and to establish a library. As poignant testimony to Bradley's high regard by the locals, Guam residents asked the secretary of the navy to allow Bradley to represent them in the United States when the navy replaced him in May 1931, just as the Great Depression plunged to its greatest depths. [72]

Following Governor Bradley's departure, political and economic conditions deteriorated under subsequent American governors as the bleak realty of depression settled over the island in the 1930s. The Great Depression crushed economic activity on the island, most noticeably by depressing copra prices and diminishing its exports, and it retarded education by limiting the number of teachers that could be hired. By 1941, there were only eighty-five miles of paved roads on the island. Most governors of Guam rejected the resolutions passed by the new Second Guam Congress. Island residents still had no right to protection by grand jury, and there were still no trials by jury. Education remained inadequate. Racial discrimination permeated the navy's administration of the island. The majority of the population depended on government support to survive during the 1930s. Navy governors squelched additional efforts (in 1933 and 1936-37) to obtain American citizenship. Congress continued to support the navy view that Guamanian residents had not improved their economic condition enough to deserve citizenship. The U.S. Navy failed to improve local civil liberties and enlarge the responsibility for self-government. The U.S. Congress perpetuated the military colonialism on Guam practiced by the navy. [73]

Only in the area of public health did the U.S. Navy markedly upgrade conditions for the residents of Guam. Greatly improved sanitation and medical services nearly eliminated leprosy and gangosa on the island. The death rate dropped dramatically between 1905 and 1940. The population of local Guamanians had increased 128 percent during forty years of American naval administration, from 9,630 in 1901 to 21,502 in 1940. The failure of U.S. Navy administration of Guam is, perhaps, understandable, even if not excusable. The primary mission of the naval governors was military defense and not civil development. [74]

|

| Figure 3-2. Original map courtesy of the Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam. Map modifications by Evans-Hatch. |

Japanese Arrive on Guam

During the 1930s, the U.S. Navy became increasingly absorbed by its mission of military defense. Japan, which had been given control of most of Micronesia [75] after World War I by a 1920 League of Nations mandate, and her activities in Micronesia became a growing distraction and cause for concern. Worried about Japan's efforts to consolidate its control over Micronesia in the late 1910s and the early 1920s, [76] the U.S. Navy once again revised its "Plan Orange" in 1927 and 1928 for an assumed Japanese invasion of Guam. It began to intercept and decode Japanese radio signals by 1929. A year later, President Herbert Hoover prohibited civil aircraft from flying over Guam (as well as Pearl Harbor, Guantanamo, and Subic Bay) in a feeble attempt to prevent foreign surveillance of the island. After Japan reneged on its obligations under existing arms treaties and closed off most of Micronesia to outsiders, and after Americans found and began monitoring patriotic Japanese nationals living on or routinely visiting Guam, who were part of the Japanese intelligence system, a board of naval officers recommended, in the 1938 Hepburn Report, that Guam be developed as a major air and submarine base. (The Navy General Board and Congress later rejected this large-scale fortification.) [77]

By the late 1930s, Japan began to build up its military on Micronesian islands, until then used primarily to fuel the Japanese civilian economy. The Japanese built a constellation of military facilities: airfields, harbors, ammunition depots, gun emplacements, barracks, and fuel storage facilities. Micronesia was to be a major staging area for planned offensive air and naval operations. Kwajalein (Marshall Islands) would later be used to support an attack on Hawaii and Wake Island. The Palau Islands were being prepared to provide support for a campaign in the Philippines. Truk (now Chuuk, Caroline Islands) was being readied as a base for amphibious landings on Tarawa and Makin (Gilbert Islands). Majuro (Marshall Islands) would be used for air strikes against Howland Island. Jaluit (Marshall Islands was being prepared for the seizure of Nauru and Ocean Island. Finally, the Japanese were making military preparations on Saipan to support a naval and air attack on Guam. [78]

The eyes of the world shifted abruptly toward Europe when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, an event marking the outbreak of World War II. Immediately, the American high command made preparations for possible military campaigns in the Atlantic Ocean and Europe against the Nazi regime in Germany the top priority. Preparations for a war in the Pacific became secondary. In late 1939 and early 1940, when the United States formulated its global military strategic plans called "Rainbow War Plans," the U.S. Navy put Guam in the lowest priority defense category, an acknowledgement that Guam could not be defended. [79]

Despite this, the United States, over the next two years, used Guam for wartime preparations against Japan and, as Japanese-American relations became increasingly strained, to defend Guam against a long-predicted Japanese attack. After Japan joined the Axis Pact with Germany and Italy in September 1940, the United States sped up its efforts to decode Japanese encrypted communications. In July 1940, the U.S. and Great Britain imposed a trade embargo on aviation gasoline and strategic metals produced for sale to Japan. Then, in mid-February 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt declared Guam off-limits to all foreign and domestic nonmilitary sea and air traffic. In February and March, Congress appropriated a total of $4,700,000 for last-minute defense projects to improve Guam's Apra Harbor, to construct new oil storage tanks at Cabras Island, and to prepare for the construction of airfields on Orote Peninsula. In July 1941, President Roosevelt froze all Japanese assets in the United States. On October 17, 1941, the last American military dependents left Guam on the USS Henderson. The last issue of the Guam Recorder was published in November. Everyone on Guam expected war to break out in the Pacific. The only unanswered questions were "where" and "when." [80]

Guam residents did not have long to wait. Shortly after 8 a.m. on the clear morning of December 8, 1941, the drone of aircraft flying over Hagatna could be heard as residents prepared to celebrate the Feast of the Immaculate Conception or began their work day as fishers, merchants, or government workers. Captain George J. McMillin, governor of Guam and commandant of the U.S. Navy on the island, had learned, two hours earlier, of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was planning to evacuate people from the capitol of Hagatna when he heard the aircraft overhead and craned his neck to look skyward. A few minutes later, war planes, with round red markings on their wings, swooped down over Sumay, on Orote Peninsula, and dropped a series of bombs, one of which hit a big Standard Oil Company tank; it immediately burst into flames and sent up black billowy clouds of smoke, obscuring the clear blue sky. Over the next few hours, Japanese airplanes bombed military targets at Piti navy yard, the Libugon radio towers, vessels in Apra Harbor, and the mine sweeper Penguin, about one mile off of the Agat beaches. The Japanese began to bomb Hagatna the afternoon of December 8. The next day, the Japanese resumed their bombing of Guam, once again, striking the Libugon radio towers again and downtown Hagatna. They also strafed [81] villages scattered throughout the island. [82]

On December 10, Japanese troops landed at widely scattered locations around Guam–Tumon Bay, Apruguan-Dungcas Beach (north of Hagatna), Bile Bay (north of Merizo on the southwest coast), Talofofo Bay (on the southeast coast), Agat beaches, and Hagatna Bay. In a short time, Japanese soldiers converged on the Plaza de Espana in Hagatna, where Governor McMillan had assembled three platoons of the Insular Force Guard (with a total of about eighty-five Guamanian men), along with a handful of U.S. Marines and sailors to defend the governor's family and American staff personnel. In the dim light of the early morning, gunfire erupted across the Plaza de Espana. Japanese soldiers closed in on the Insular Force Guard and American solders and sailors in what Governor McMillan later described as a "hopeless" situation. [83] Around 7 a.m. on December 10, McMillin signed a letter of surrender, less than six hours after the Japanese stepped foot on Guam. The flag of the Rising Sun was immediately raised on the flagpole in the plaza, just as the sun rose over Guam. [84]

By the end of December 1941, Japan completed its conquest of Micronesia. On December 23, Americans on Wake Island, about 2,000 miles to the east of Guam, surrendered to Japan after endless air strikes over a two-week period. Japanese control of Micronesia extended from Wake Island and the Mariana Islands in the north to Palau in the far southwest and the Gilbert Islands in the southeast. The Japanese used these Micronesian islands for offensive operations until September 1943.

Guam remained under Japanese control for the next two and one-half years. Immediately after the United States surrendered, the Japanese rounded up all Americans and foreigners and shipped them to Japan as prisoners of war. (Six American sailors remained loose on the island for several weeks before all but one, George Tweed, were found and executed by the Japanese.) Many Guamanians, including those in the Insular Force Guard and nurses, were treated as prisoners during the day and forced to work involuntarily as unpaid field workers, planting and harvesting crops, stevedores who unloaded ships, miners at a manganese mine at Libugon, and as nurses. The Imperial Japanese Army soon created the "Minseisho," a section of the military responsible for civil government on the island. The Minseisho performed many functions, including issuing an identification pass, or "dog tag," for every Guamanian, issuing money, rationing food and other commodities through coupons, and establishing quotas for the monthly production of food for the Japanese troops. As the supply of food dwindled, more and more Guamanians, who scattered into the countryside during and after the invasion, began harvesting their own food from the sea and the land. A shortage of money gave rise to bartering among the Guamanians and the 6,000 Japanese troops, who were garrisoned at Sumay on Orote Peninsula. Although Japanese administration of Guam was harsh at first, Japanese rule relaxed after January 14, 1942, when the Japanese naval guard force took over the administration of Guam. The Japanese did not confiscate the islanders' property, even though marshal law was in effect. Most islanders did not experience extreme hardship until the last few months of Japanese occupation. According to historian Robert Rogers, "the islanders adopted an attitude of guarded submissive neutrality toward the Japanese while hoping for the return of the Americans." [85]

When the return of Americans did seem imminent, the Japanese imposed much harsher security measures, and drafted nearly everyone to raise food crops for the Japanese soldiers or build defensive structures. After American bombing of Guam became sustained in the late spring and summer of 1944, the Japanese moved Guamanians to internment camps in the interior and eastern coastal areas at Maima, Tai, Manengon, Talofofo, Inarajan, and several other places, where although food was often scarce, shelter temporary, and living conditions impoverished, they were away from areas where fighting later occurred. [86]

Americans Return to Guam

The United States began sporadic counter attacks in the Pacific not long after the Japanese invasion of Guam. The U.S. made air attacks on Tokyo in April 1942. In May and June, the American Navy halted Japanese advances by winning major victories in the Coral Sea and also near Midway Island. This was the first major turning point in the Pacific War. U.S. troops wrestled Guadalcanal from the Japanese in the summer of 1942. From then on, the United States took one Pacific island after another from the Japanese, within Micronesia and outside it, in stepping-stone fashion. As early as January 1943, American aircraft and submarines attacked a Japanese cargo carrier inside Apra Harbor. Seven months later, on August 27, 1943, the USS Snapper hit the Japanese Tokai Maru, anchored in Apra Harbor. The Tokai Maru sand, coming to rest on the bottom next to the German ship Cormoran, sunk during World War I. The first major American counter attack in Micronesia took place in November 1943, when the U.S. Pacific Fleet made landings at Tarawa (Gilbert Islands) and, then, captured Kwajalein, Wotje, Jaluit, and Maloelap (all in the Marshall Islands), 1,500 miles east of Guam, in February 1944. (This offensive thrust from the east replicated an earlier "Orange Plan" devised by the U.S. Navy.) Also in February 1944, the Americans (Admiral Raymond Spruance's Fifth Fleet) destroyed the important Japanese base at Truk [Chuuk] Lagoon (Caroline Islands) about 600 miles southeast of Guam. Then, on February 23, 1944, American aircraft carrier-based airplanes bombed the Japanese airstrip on Orote Peninsula, marking the beginning of the end of Japanese occupation of Guam. [87]

The Mariana Islands were considered the first line of defense of Japan itself. In April 1944, a U.S. submarine torpedoed a Japanese submarine tender. In May 1944, Americans began regularly bombing Guam and other islands in the Marinas. In late June and early July 1944, U.S. bombing strikes against Japanese targets in the Marianas, including Guam, increased in intensity. The U.S. Navy's Central Pacific Offensive attacked and captured, first, Saipan, then, Tinian in June and July, putting Japan within range of U.S. B-29 bombers. As the U.S. Marine Corps fought the Japanese on Saipan beaches, nearly 100 U.S. dive-bombers blasted Guam. The U.S. Navy's Fifth Fleet bombarded a Japanese minelayer at Cabras Island the next day. [88]

As the U.S. offensive gradually advanced toward Japan and the American threat grew, the Japanese on Guam, just 1,350 air miles from Tokyo, built up their defenses. In October 1943, the Japanese began construction of an airstrip on Orote Peninsula (the present site of Sumay golf course). Another airstrip was begun on the island's central plateau (Jalaguac-Tiyan, the present location of the Agana Naval Air Station). Both airstrips were later bombed by the U.S.

|

| Figure 3-3. U.S. military commanders on Guam, December 1944. From left to right: Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, U.S.N. (front seat), Commander in Chief Pacific, and Commander in Chief Pacific Ocean Areas; Rear Admiral Forrest B. Sherman, U.S.N., (on Nimitz's staff); Vice Admiral J. H. Hoover, U.S.N., Commander Marianas Area; and Major Generall Henry L. Larsen, U.S.M.C., Island Commander (and, therefore, Governor of Guam), 1944-46. |

After the first American air raids on Guam began in February 1944, the Japanese ordered Guamanians and Koreans, who had been brought to Guam as laborers, to build shelters, usually dugouts topped with coconut logs and tunnels dug into hillsides and cliffs. The Japanese ordered the construction of new roads, pillboxes, and gun emplacements on the beaches and elsewhere. As U.S. bombing intensified in the early summer of 1944, the Japanese supervised the continued construction of ground defenses, mostly on the western side of the island. Barbed wire, mines, and obstacles were put underwater along the reefs and lagoons. Dummy cannons were mounted all around the coasts and on Cocos Island. Guamanian and Korean laborers dug tunnels in the hills overlooking possible American landing sites, particularly in the ridges above Asan, later named Bundschu Ridge and Nimitz Hill (central portion of Bundschu Ridge) and behind Agat Beach on Mount Alifan. [89]

Final preparations for the American ground invasion of Guam began in early July 1944. On July 8, United States aircraft and ships attacked the island day and night for thirteen days in a systematic "softening" of Japanese defenses on Guam. On July 14, the Navy's underwater demolition teams swam in toward the beaches, checked Japanese barriers, and, three days later, destroyed obstacles on the planned assault beaches, including tank traps, cribs filled with coral, and wire barriers. By July 20, Navy frogmen had blown 640 obstacles off Asan Beach and 300 off Agat, making the actual landing of troops on these beaches possible. "The American bombardment of Guam," Robert Rogers emphasized, "had gathered momentum from 18 July on to become, by the morning of 21 July, the most intense crescendo of conventional firepower ever inflicted on any locality in the Pacific war." [90] The U.S. fleet assembled off Guam's western shore on the morning of July 21 was enormous: eleven battleships, twenty-four aircraft carriers, and 390 support ships. [91]

Throughout the night and early morning of July 21, 1944, all American assault units moved to their assigned positions off Asan and Agat beaches. A total of 54,891 men poised for attack. [92] On the morning of July 21, two major American forces landed northeast and southwest of Apra Harbor. The 20,328 men of the Marine Division (under Major General Allen H. Turnage) landed on Asan beach, the northern invasion sector. In a three-pronged attack, the marines slowly advanced toward Adelup Point (in the northeast), central Asan beach, and Asan Point (in the southwest) under heavy mortar, artillery, and small arms fire from Japanese defensive positions. At the end of the day, the marines had taken Adelup Point and had dug in on the ridges behind Asan Point and Asan Village. On July 22, after surviving a Japanese counter attack, the marines moved up the steep hills toward Mt. Chachao. Serious Japanese counter attacks that followed during the next three days were eventually beaten back during bitter fighting and the loss of 3,500 Japanese soldiers. [93]

The Americans' second major force landed on beaches at Agat, south of Apra Harbor, in the southern sector operation. The 9,886 men of the First Provisional Marine Brigade (led by Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr.) were the first to land on the beach, under intense Japanese defensive fire. The next day, the 17,958 men in the Seventy-seventh Infantry Division (led by Major General Andrew D. Bruce) lent support to the marines in holding their beachhead. On July 25, a combined American force of 34,563 men secured the Agat area, between Agat Bay and Apra Harbor. The First Provisional Marine Brigade then turned northward to meet the Third Marine Division, heading south from Asan, to cut off the eight-square-mile Orote Peninsula, where 3,100 Japanese troops were trapped. The two groups met on July 27, thus securing an area extending from Adelup Point in the northeast to Facpi Point, south of Agat. [94]

Once the Americans had taken most of the land between the beaches and the "Force Beachhead Line" (a north-south line extending from Asan to Agat behind the coastal peaks of Mt. Chachao, Mt. Tenjo, and Mt. Alifan), two major military objectives remained: Orote Peninsula and the interior of Guam. After a three-day push to destroy the weary but resistant Japanese on the peninsula, the First Provisional Marine Brigade, preceded by U.S. air attacks and naval artillery, captured the Orote airstrip and swept to the tip of the peninsula on July 29. At the same time, the Third Marine Division and the Seventy-seventh Infantry pushed the remaining Japanese to the east and north, through mountain terrain. The two forces merged in early August and together made the final push toward Ritidian Point in an eventually successful effort to drive the Japanese off of Guam on August 8. [95] One last stronghold of Japanese resistance, Mt. Santa Rosa, was attacked by the army's Seventy-seventh Division. After two days bitter battling, the army gained the summit. On August 12, 1944, army troops stormed and captured the last Japanese stronghold near Mt. Mataguac. Once again, Guam was in American hands. [96]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

wapa/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 08-May-2005