|

War in the Pacific

War in the Pacific National Historic Park An Administrative History |

|

Chapter 5:

PRE-LEGISLATION PLANNING AND PREPARATION — 1952 - 1978

Introduction

The planning that precedes the establishment of a national historical park varies significantly from park to park. Each proposed park presents unique political, social, economic, logistic, and environmental factors, and they all must be addressed by the planners. The underlying Park Service proposal must be well thought out since the service must live with their creation. [120] War in the Pacific National Historical Park on Guam was no exception. The climate, topography, rapidly changing economy and remoteness from the continental United States all combined to greatly complicate the pre-park planning, and dramatically increased the factors that had to be considered. Park concepts were discussed for almost twenty-six years. A war in the Pacific park was first mentioned in 1965; the park wasn't created until 1978. This chapter examines the events, discussions, planning, and proposals of that period.

The War in the Pacific National Historical Park was created by legislation enacted in 1978. However, federal government studies of Guam's historical significance and recreation potential officially began in 1952 when the Park Service was asked by the Office of Territories to conduct archeological and recreational studies. [121] This effort resulted in an inventory of prehistoric sites as well as evidence of Spanish influence on the island. Thirteen years later, NPS investigators again visited Guam, this time at the request of Guam's Governor Manuel M. L. Guerrero. The September 19, 1965, Territorial Sun article reported that,

An NPS study group that visited Guam in June 1964 recommended that two parks be established on Guam: A National Seashore Park, and an historical park commemorating and interpreting the war in the Pacific. The group also recommended that the Government of Guam create a territorial park system to identify and preserve historical material and develop public park areas.

This group was comprised of Glenn O. Hendrix, Chief of New Area Studies and Master Plans, Western Office of Design and Construction; Edward A. Hummel, Regional Director, Western Region; and Douglas Hubbard, Chief Park Naturalist, Yosemite National Park. [122]

This 1964 visit culminated in a proposal recommending that a Philippine Sea National Seashore Park and a War in the Pacific National Historical Park be established. The 1965 proposal identified the purpose of the historical park as being the interpretation of World War II in the Pacific with particular emphasis on the battle for Guam.

Two years later, in January 1967, Representative Richard C. White (D-Texas), who had served with the U. S. Marine Corps during the Guam landing, introduced House of Representatives Bill 2911, which would have authorized the creation of War in the Pacific National Historical Park. (See Appendix 5 of this document for Representative White's introductory remarks.) In a March 28, 1967, memorandum to the Office of the Solicitor General's Legislative Counsel, the Director of the National Park Service reported that the service was studying the possibility of a War in the Pacific Park and expected to complete a master plan in July of that year. The director also indicated that the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments would be considering the issue at its April 1967 meeting. [123] The possibility of an NPS park was echoed on Guam as well as within the District of Columbia. The Guam Daily News reported that,

Four NPS employees are scheduled to arrive on Guam on February 15 to prepare a preliminary report with data in support of legislation introduced by Representative Richard White (D-Tex) to establish an historical park. The report would be disseminated for public comments before being submitted for ultimate inclusion into a park master plan. The NPS group will consist of Richard Barnett; Bruce Black, naturalist; Merrill Mattes, Historian; and Ronald Mortimore, landscape architect. [124]

The master plan group explored Guam for three weeks, from February 15 through March 7. Existing Park Service records indicate that the group consisted of Richard W. Barnett, leader; Merrill J. Mattes, historian; Bruce Black, naturalist; and Mark Malik, landscape architect, with the assistance of Paul Souder, chief of the Guam Department of Land Management. The group explored landing beaches, coral reefs, Japanese caves, shelters, and fortifications using a helicopter and a forty-five-foot boat, both supplied by the navy, and a jeep supplied by the Government of Guam. The group was guided by Guam resident Jesus Lizama. While on the island, the group conferred with the Governor of Guam, the 9th Guam Legislature's Committee on Parks and Monuments, and the governor's Parks and Monuments Advisory Committee. [125]

|

| Figure 5-1. War debris on the Agat Invasion Beach, February 1967. National Park Service photograph. Pacific Great Basin Support Office, file P6SOI-WAPA. |

The authors of the 1967 Master Plan identified the "Management Category" of the Guam sites as "Historical," and Theme XXI, "Political and Military Affairs Since 1865," as the relevant classification under the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. They justified suspending the fifty-year rule on the grounds that the tropical climate and other factors were resulting in a rapid loss of the island's historic sites and artifacts.

The 1967 planners advocated that the park should consist of two major units — the Asan Unit and the Agat Unit. The park would also include the Mount Tenjo approach and overlook. Most of the land in both landing beaches was part of the navy reservation; however, the NPS group expressed optimism that they could work with the navy and obtain access as well as rights sufficient to allow for interpretation. They proposed that the headquarters for the future park be on Asan Ridge, providing an overlook of the Asan landing area. A one-way interpretive road would permit vehicular traffic between park headquarters and an Apra Harbor overlook. Circulation for the Agat Unit would be by spur road connections.

|

| Figure 5-2. Agat Beach in February 1967. Net fishermen in foreground. Houses along shoreline were within proposed park boundary. National Park Service photograph. Pacific Great Basin Support Office, file P6SO1-WAPA. |

While on the island, the group also investigated land ownership. They discovered that Asan Point was administered by the navy as a hospital annex; Apaca Point was used as a civilian recreation area by the navy; and various strips of seashore land were owned by the Government of Guam and were undeveloped. The upland areas were also owned by the Government of Guam and were steep, wooded, or grassy and used for limited grazing or cultivation. There was a public school on Adelup Point. Approximately one-quarter of the Agat Unit was wooded; the rest had a few residences or was being used for grazing or agriculture. Similarly, the upland areas in the Asan-Piti area were predominately undeveloped and being used for limited grazing or cultivation. There were limited commercial uses on lowlands near the coast. The planners concluded that, "Present agricultural and grazing uses are considered compatible with the purposes of the park. However, changes in intensity or methods could change the situation." [126]

Toward the end of the 1967 master plan, procedural steps were delineated which were to be implemented when and if enabling legislation were enacted authorizing a park's creation. The plan identified two phases of the proposed park's development: Phase I was identified as the "Planning and Initialing Action," phase. The objective of this phase was to ensure that, "developments are well conceived, and that human relations get off to a good start in an atmosphere of trust and understanding with park neighbors." [127] Phase I was also identified as the time to continue work on the master plan, the time to formulate and initiate "action plans," and a time to commence interim operations. Phase II was to be a time of development, a time of construction. The planners included language under Phase II regarding staffing that is enlightening: "Because of severely limited housing on Guam, housing for the superintendent and historian should be provided first." [128] Therefore, the 1967 planners planned on both a superintendent and a historian to be immediately assigned to the new park.

|

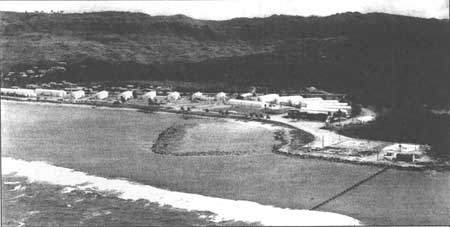

| Figure 5-3. U.S. Navy facilities on Asan Point in February 1967. National Park Service photograph. Pacific Great Basin Support Office, file P6SO1-WAPA. |

Not everyone within the Park Service agreed that Guam was the most appropriate location for a War in the Pacific Park. In August 1967, Robert Utley, the service's chief historian sent a memorandum to the Chief, Division of New Area Studies and Master Planning. The Utley memorandum served as the cover, transmittal sheet for two other memoranda: one from Roy Appleman, Chief of Park History Studies, and the second from Ed Bearss, then a research historian for the service. Both Appleman and Bearss argued strongly that Guam was not the best location for a war in the Pacific park, and, further, that if the park was located on Guam, the proposed park location on the island was historically inappropriate. Utley expressed agreement with Appleman and Bearss in his transmitting memorandum. Utley noted that Appleman had been a combat historian in the Pacific during World War II, and Bearss had served with the Marines in the Pacific. Utley concluded that these experiences made both men particularly well qualified to comment on the master plan for the proposed park.

The Bearss memorandum that Utley forwarded argues that the battle for Guam was not the turning point for the war in the Pacific, nor was it even the most important battle in the Marianas — Saipan probably was. Bearss stated that Midway, Wake, and Attu probably had greater claim to importance in the Pacific theater than did Guam. He also mentioned that Guam was not the only American soil lost to the Japanese; they also took some Aleutian Islands (Attu, Agattu, and Kiska) and Wake. Additionally, he argued, there were other islands within the Trust Territories-Pacific that were of equal or even greater importance than was Guam, including Kwajalein and Eniwetok in the Marshalls and Palau in the Carolinas. Furthermore, Bearss argued, if the Park Service were to establish a visitor center where it would tell the story of the war in the Pacific, it should be built on Oahu on or adjacent to Pearl Harbor. Not only was Hawaii more historically correct, he argued, its statehood and proximity to the United States mainland would result in more American visitors. Bearss suggested that if the service created a park on Guam, it should more appropriately be called "Battle of Guam National Historical Park."

Bearss concluded his three-page memorandum by arguing that not only is Guam an inappropriate location for such a park, the proposed park boundaries were historically unsound. With few exceptions, he argued, the Japanese rarely contested the beaches. Japanese beach defenses were usually eliminated by pre-landing naval and air bombardment; therefore, the Japanese established their main defenses on high ground overlooking the beaches and fired mortars and artillery from there. Consequently, Bearss would have the park service locate the visitor center on one of the high points — Mt. Alifan, Mt. Chachao, or Mt. Tenjo. As to the rest of the park, Bearss proposed the following boundaries in his memo:

Agat: A relatively small portion of the beach connected to a strip of land extending inland to the Force Beachhead Line, excluding the towns of Agat and Santa Rita.

Asan-Piti: Again, only a small, limited amount of beach should be included together with access to Fonte Plateau. The park, Bearss argued, should include both Fonte Plateau and Orote Peninsula.

Mt. Tenjo and Mt. Alifon: This unit should be expanded to include the ridge stretching from Mt. Alifan in the south to Fonte Plateau in the north. A one-way road should be constructed which would link the Agat Unit with the Asan-Piti Unit.

In addition to the Bearss memorandum, the Utley memo transmitted comments by Roy Appleman. Appleman reported that both the Secretary of the Interior and the Director, Office of Territories, were exploring the idea of a war in the Pacific park being located on Wake Island. If they concluded that Wake was not an appropriate location, Appleman stated, Oahu would certainly be more appropriate than Guam. Appleman also agreed with Bearss regarding the proposed park boundaries. Appleman stated that if the park were to be located on Guam, the high ground would be more historically appropriate for the park, not the beaches. The ridgeline connecting Mt. Alifan and Fonte Plateau should be the principal park area, he argued. He suggested that the park should include limited areas at the northern and southern beaches, both connected to the ridgeline by a road that went from the southern beach over Hill 40 to Mt. Alifan. The road would then continue north along the ridgeline to Mt. Chachao, then down to the northern beach, passing Fonte Plateau as closely as possible. Appleman also noted that the visitor center that was proposed in the master plan (on Asan Ridge) was considerably below the elevation of the Force Beachhead Line, and it should be located on this line. Appleman continued:

A battlefield park along the lines indicated [in this memo] would need to pre-empt only a small part of the 6 miles of beaches now proposed. This would free the remainder for other uses, which one can feel confident will be pressed for in any event. The present plan apparently contemplates that the beaches should be used for swimming, bathing, and related water sports. I do not think this use should be part of an historical battlefield park. Let that development take place outside the park and let it be operated by other officials or persons for that expressed purpose if it is to be done. [129]

Although a thorough search was conducted at several NPS archives as well as at the park itself, no documentation could be located that represented a continuation of this dialogue. The paper trail simply vanishes as if the siting issues raised by Utley, Bearss, and Appleman were never addressed. And, this is entirely possible since ultimately the presence of the park on Guam was strongly advocated within the United States Congress. The park was created from the top down. Legislation creating the park was introduced and supported by representatives who were either personally involved in the battle for Guam, or were involved in the Pacific Theater.

The first bill introduced that would have created a War in the Pacific National Historical Park was sponsored by Representative Richard White in 1967. White had served with the United States Marine Corps during the Second World War and participated in the Guam landing. White's 1967 bill failed to pass. Undaunted, Representative White introduced similar legislation to the 91st Congress in 1969 (H. R. 5580), which also failed. [130] Nonetheless, the Park Service continued planning for a park on Guam. In 1969 H. P. (Phil) Troy, the Chief, Branch of Appraisals made his second trip to Guam. He had been on the island in 1967 to value land preliminarily identified as probable park land (his estimates of land values are mentioned above). Troy memorialized his second, 1969, trip in a June 5, 1969, memorandum he wrote to the Park Service's Chief, Division of Land and Water Rights. Troy reported that the Government of Guam had agreed to convey all its lands within the proposed park boundaries to the National Park Service. The value of the land the Government of Guam was to convey to the Park Service, according to Troy, was $1,085,000, which was double NPS' credit of $540,000. [131] However, the Government of Guam wanted land worth $821,900; therefore, the entire transaction would leave a net balance due NPS of $276,000, and that balance was to be used by the Government of Guam to acquire private in-holdings within the proposed park that it would convey, in turn, to the service. Troy exclaimed in his memorandum that the result of his negotiations would probably result in the service acquiring lands for the park without needing additional appropriated funds. [132] The Secretary of the Interior echoed this conclusion in an August 28, 1969, letter to Melvin R. Laird, then Secretary of Defense:

The commercial port now being constructed on Cabras Island is located on land that has been deeded to the Government of Guam. In exchange, the Government of Guam is presently preparing a deed transferring lands in and around the villages of Asan, Piti, and Agat to this Department. This land to be deeded comprises nearly all of the areas included in the master plan for War in the Pacific National Historical Park. It, therefore, appears that this proposed park could become a reality at little or no cost to the United States.

The enclosed Land Use and Ownership Map illustrate the lands to be included in the park which principally are those for which the deed is presently being prepared. In the northern unit, just across Marine Drive from the Navy Hospital Annex, is a small tract that is a part of the former Asan Tank Farm, presently owned by the Navy but unused and improved only with an apparently abandoned Quonset building formerly utilized as a bowling alley. This tract contains approximately 25 acres. It has been selected as a key development site in the park proposal and is particularly suitable for this purpose since the tract adjoining it on the south is presently owned by this Department. In this area would be located the park headquarters, several interpretive facilities, and service and housing structures. A second area, Asan Point Overlook, located across Marine Drive to the west and adjoining but south of the hospital complex, is particularly vital for presenting to the visitor the historical account of World War II as it applies to the invasion beaches of Guam. [133]

The fact that the Secretary of the Interior's letter echoes sentiments expressed earlier by Troy in his June memorandum is not surprising since it appears that Troy actually authored the letter sent to the Secretary of Defense over the signature of the Secretary of the Interior. [134]

The above request for land transfer was apparently successful. An October 1970 article in the Pacific Daily News, announced, "National Park For Guam." The article reported that,

Rear Admiral Paul E. Pugh announced that the Asan Point Overlook, a hill and plateau overlooking the initial major landing area of United States forces on July 21, 1944, has been transferred to the Department of the Interior. This will be a national historic park planned for Guam to commemorate the bravery and sacrifice of those participating in the Guam campaign in World War II.

The land was transferred by the Officer in Charge of Construction, Marianas for the Department of the Navy to the Department of the Interior and contains 16.45 acres. This property was formerly part of the Old Asan Point Civil Service Community, and is adjacent to the U.S. Naval Hospital Annex. [135]

Unfortunately, the land transactions between the Park Service and the Guam government didn't go as smoothly. According to a February 26, 1971, memorandum from the director of the Park Service addressed to the Director, Office of Territories, Guam had agreed to convey 877.41 acres to the Park Service. However, on April 3, 1970, Guam conveyed only 507.5 acres. After additional discussions, the Government of Guam conveyed what it reported was the balance of the land due the Park Service under the agreement. Unfortunately, it was the wrong land. This memorandum asks the Director, Office of Territories to assist the Government of Guam find its copies of the maps showing precisely what land it had agreed to transfer to the service. [136] In early March 1972, Robert L. Barrel, General Superintendent, Hawaii Group traveled to Guam in an attempted to resolve the confusion. He was accompanied by Philip E. Troy, Chief Appraiser, Lands Division, NPS, and Bruce Rice an NPS appraiser. Portions of his seven-page, single-spaced trip report cast some light on the problem:

Many land records were destroyed during World War II. Other documents seem to get lost. Many details are exceedingly difficult to pin down and to keep pinned down. There are disagreements between the Executive and Legislative branches of the Government. Land titles are cloudy and various parcels are in a disputed status. The Territorial government is resentful of the U. S. Navy and the Navy in turn sometimes appear [sic] contemptuous of the Government of Guam. [137]

Notwithstanding these reportedly enormous difficulties with chains of title, Barrel pressed on. His trip report continues:

The following matters were discussed in some detail with Lt. Governor Moylan and most members of the Department of Land Management. It was not agreeable to the Executive Branch for me to broach the details I discussed with them to the Legislature. There is considerable jealousy between the two branches and it seemed politic to accede to the wishes of the Governor and his staff at this time. Therefore, I have no concurrence from the Legislature beyond that which was given at the public hearings held by the House Subcommittee in January.

Although Mr. Barrel may have been successful discussing these issues with the governor's office, the sad fact was that Section 13525 of the Code of Guam prohibited the Governor of Guam from agreeing to exchange land without the approval of the Guam legislature. [138]

Barrel's second 1972 trip to Guam was destined to throw the entire concept of a war in the Pacific park located on Guam into serious doubt. In fact, what he found on the island during his September trip that year ultimately resulted in the Park Service deciding to discontinue supporting the establishment of the park altogether. The Park Service had received word that the Government of Guam, with the concurrence and assistance of the Army Corps of Engineers, was planning on constructing a small boat harbor within the boundaries of the proposed historical park. Barrel flew to Guam on September 26 to discover it wasn't a harbor that was being considered at the time, but rather a small boat ramp. In his later trip report, Barrel reported that the ramp, ". . . would be damaging, but not fatal, to the historic values in that area . . .." [139] However, he reports in the next paragraph in the same trip report, that in a meeting with representatives of the Government of Guam he argued that NPS would object to the construction of the ramp since the ". . . construction would definitely have an adverse effect on the historical values. . .." Barrel continues, "Nobody from the Government of Guam appeared to agree with me. Members of the Government of Guam made it clear that they thought the impact on historical values was so minimal as to be imperceptible, and that I was being bull-headed, tendentious, and was standing in the way of progress." Barrel reported that the meeting was "somewhat stormy." [140] Having done his part for the Park Service's public relations, Barrel, while driving around the island, discovered an "urgent and appalling development." According to Barrel, the island planning commission had approved a zoning change that permitted the construction of a housing development, "in the heart of the Asan-Piti unit." Barrels continues, "If this subdivision is build, it will tear the heart out of the single most significant unit of the proposed park, eliminating or impinging upon the headquarters and major interpretive site, [and] wiping out much of the most significant battleground." [141]

Barrel's discovery of the approved subdivision in the Nimitz Hill area was considered a profoundly significant issue by Park Service staff. Curti Bohlen, the Acting Assistant Secretary of the Interior sent Carlos Camacho, the Governor of Guam a letter dated October 10, 1972, asking the governor to not approve the zoning change. (Apparently, under then-existing Guam statutes, the Governor had the power to essentially veto zoning changes approved by the Guam Land Use Commission.) [142] Although no records of additional correspondence could be found, it appears that the zoning change was adopted, and construction of the housing development commenced. On February 21, 1973, Bruce Rice with the Lands Office of the Denver Service Center, reported to Robert Barrel, State Director, Hawaii, NPS, that the developers had paid $1,950,000 for the land and they were planning on building 170 homes priced from $45,000 and up. Rice also mentioned that the Government of Guam had recently built a sewer outflow at Agat Bay on land they had deeded to the Department of the Interior for use as a national historical park. [143] Robert Barrel responded by sending a memorandum to the director of the National Park Services' Western Region on March 1, 1973, where he reported that land prices on Guam have doubled in the previous twelve months, and that the land acquisition costs for the park now would be approximately $7 million. Barrel also reported that construction had started on the Nimitz Hills Estates housing development, and, in his words, "I honestly think that War in the Pacific [has] gone down the drain." [144] On March 19, 1973, the Director of the Western Region notified the Associate Director, Legislation, National Park Service, that the Western Region would no longer support the concept of the park on Guam:

Enclosed are copies of memorandum from Hawaii State Director Barrel, and Lands Appraiser Bruce Rice, Denver Service Center, concerning the subject proposal. These memorandums describe what appears to be abandonment by the Government of Guam of any controls that would have assisted in the establishment of this area.

Under the circumstances, and unless otherwise advised by your office, it is our intention to discontinue any further expenditure of resources in the compilation of data to support [the park in Guam] legislation.

We further suggest, that if requested to comment on the bills before Congress [H. R. 1596 — War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam] that the Service and Department submit a negative report based on the loss of integrity due to developments incompatible with the purpose of the historic park.

Please remove this proposal from the Western Region's legislative program. [145]

On April 23, 1973, the Chief, Division of Legislative Coordination and Support sent a memorandum to the Chief of the Division of Legislation, indicating that the National Park Service was submitting an "unfavorable" report on H. R. 1596 [War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam]. [146]

The decision to discontinue supporting the concept of a war in the Pacific situated on Guam took deep and lasting roots. In July 1974, Rogers C. Morton, then Secretary of the Interior sent a letter to Governor Camacho (Governor of Guam), agreeing to the idea of entering into a twenty-five-year lease with the Government of Guam conveying the lands that NPS had planned on using for the park. [147] The lease would permit the Government of Guam to develop the land into a recreational park. The idea of a recreational park either on Guam or Saipan "commemorating" those Americans who died in the July 1944 landing was so attractive to some that James Watts, then Director of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, traveled to Guam and Saipan in early 1975, to promote the idea. Park Service staff got wind of the proposal, and Robert M. Utley, the Assistant Director, Park Historic Preservation sent a memo to the Associate Director of Legislation urging that the Park Service object to the proposal to establish a War in the Pacific National Historical Park on Saipan with swimming pools, tennis courts, and picnic areas. The author argued that the concepts of "recreational" park should not be confused with "historical" park. If a historical park was being considered, recreational activities should not be included. The author continued by reporting that Saipan had retained a great deal more historical integrity than did Guam, and if a War in the Pacific park were to ever be built it should be built on Saipan, and in the interim the historical integrity of Saipan should not be destroyed with recreational facilities. [148] The record contains additional evidence that the Park Service seriously considered the idea of a War in the Pacific National Historical Park on Guam a dead issue. Philip Stewart, Chief, Division of Land Acquisition send a memorandum to the Chief of the Division of Legislation reported that the Director, Office of Territorial Affairs is working to return the 850 acres to the Government of Guam that had been conveyed to the Department of the Interior for use as a park; [149] and in July 1975, Richard Curry, then Acting Director of NPS, wrote to Legislative Counsel reporting that the Park Service was not interested in a park on Guam but would like to leave the question open for the possible siting of a war in the Pacific park on Saipan. [150] The depth of Interior's loss of interest in a historical park on Guam is illustrated by a December 1975 letter from the Governor of Guam to the Department of the Interior repeating the one-and-one-half-year-old request for a twenty-five year lease empowering Guam to manage the lands originally intended for use as a park. The Governor reported in his letter that national register sites situated on that land were being damaged. The author reported that former Japanese bunkers were being used as domestic animal pens, land was being cultivated, and other areas used for parking lots. [151]

The National Park Service, the Department of the Interior, the Department of the Defense, and the Government of Guam may have all considered War in the Pacific National Historical Park on Guam a dead issue; however, they all underestimated the powers of resurrection enjoyed by those with offices inside the beltway of the District of Columbia. Immediately after the Department of the Interior submitted an unfavorable report on H. R. 4262 (the third bill introduced to establish a War in the Pacific park), Antonio Won Pat, the representative for Guam in the House of Representatives wrote to Thomas Kleppe, then Secretary of the Interior, asking why the turn-around after supporting the idea of the park for over a decade. Won Pat wrote that he was well aware of NPS' concern regarding the housing development near Nimitz Hill, but he wondered why one relatively small housing development would prove fatal to a proposed 2,751-acre park, particularly when the proposed park was also perceived as being several geographically dispersed units, and most particularly, when the housing development is nestled between hills and not viewable from most of the park. Won Pat also expressed wonderment that the decision to abandon the park idea had been made without anyone from the National Park Service bothering to go to Guam and investigate the impact of the completed development (Barrels had seen only plans). [152] After meeting with Representative Won Pat, Robert Utley, Assistant Director, Park Historic Preservation, recommended to the Associate Director, Legislation, that perhaps a visit to Guam by NPS staff might be appropriate. It might be wise, argued Utley, for staff to determine if their arguments of loss of integrity actually had any merit. [153]

Robert Barrel went back to Guam. He arrived on May 18, 1976, and super typhoon Pamela arrived the next day. Barrel was able to extricate himself from the rubble long enough to express a change of heart about the park. After touring the proposed park lands, he recommended that the Department of the Interior support the legislation, provided certain conditions were met:

1) Apra Harbor overlook should not be included,

2) the Japanese coastal guns should be accessed from Route 6,

3) the proposed NPS development should be moved from Asan Ridge (where there is insufficient room) to Asan Point,

4) not build a trail up Hill 40,

5) obtain zoning controls limiting building height in the Mt. Tenjo and Asan units, and

6) do not include Nimitz Beach.

Barrel concluded that the Nimitz Hill Estates development is not a problem after all since the truly historical area is the beach between Adelup and Asan points, the steep slope up to Fonte Plateau, and areas on Fonte Plateau itself. And, the housing development does not adversely affect any of these areas. [154] On August 24, 1976, John H. Davis, Acting Regional Director, Western Region announced that he was sending a four-person study group to Guam in September to up-date the 1967 proposal for the establishing War in the Pacific National Historic Park on Guam, and the up-date would incorporate changes suggested by Barrel. [155] It would be 1978, or thirteen years after the first official proposal, before the United States Congress created the proposed historical park on Guam. Every bill introduced for the establishment of the park was introduced by Representative White, including the bill that was passed into law.

During these years of planning, abandonment, and born-again support, the economics of Guam continued to change. Tourism was becoming a substantial portion of the island economy, island population was becoming more centralized in urban areas, demand for general recreation areas was increasing, and the actions of public officials, including NPS staff, was becoming more transparent as the result of island news coverage becoming more thorough. The number of Japanese tourists who began arriving on regularly-scheduled commercial flights in the 1960s, increased. In 1963, 1,500 tourists vacationed on Guam; by 1972 the number had increased to 150,000. With the growth of tourism came increasing pressure to develop both physical facilities as well as a political infrastructure to provide for the arriving vacationers. By 1972, there were 2,500 hotel rooms on the island, and the Government of Guam launched programs focused on both the preservation of historical physical features as well as planning for orderly development of the land. A 1976 report inventoried historic and prehistoric sites on Guam, including forty-four sites around the island on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1977, the Guam government was deeply involved in its planning efforts with an expressed intent to follow the general philosophy of the State of Hawaii by establishing land use districts for the entire island. In 1973, the Guam government completed a study of outdoor recreation on Guam. Both the 1977 planning work and the 1973 recreation plan expressly provided for the hoped-for NPS historical park. Additionally, the formal 1977 NPS proposal advocating the creation of the park was reviewed by the Government of Guam, including the governor, which concurred with the proposal that a World War II historical park be established on the island. Unfortunately, there were financial and demographic factors militating against such a park.

Capitalists began investing in beachfront resort hotels, residents opened restaurants, duty-free retail shops and intra-island transportation connecting the resort hotels with the new restaurants and shops were all developed. The island's metamorphosis from military base to Japanese tourist destination added new layers of financial and political complexities. The Park Service was no longer considering simply creating a historical park on an island dominated by the United States Department of Defense, it was now forced to deal with new local zoning and planning regulations of the local government agencies that promulgated and enforced them. The Park Service also found itself dealing with rapidly increasing land prices as well as an increased awareness by land owners of the value of their land. Although the promise of tourism served to advance arguments of the pro-park advocates, it also added serious time pressures to planning efforts. Escalating land prices resulting from increased tourism necessitated rapid land purchasing. Valuable, coveted beachfront land was identified as probable park lands. Increasingly, beachfront property north of the intended park was being developed with high-rise resort hotels. Topography and Andersen Air Force Base barred further northward commercial development, placing more pressure on lands elsewhere on Guam, including those needed for the park. It became apparent to many planners both within the Government of Guam and the Park Service by the late 1960's that land privately owned along the beaches had to be purchased quickly. Delays could only result in escalating prices, and possibly even resorting to condemnation proceedings, which would have been a devastating public relations development. A 1967 letter from Paul B. Souder, the Government of Guam's Director of Land Management, to Richard W. Barnett, NPS Planning and Service Center in San Francisco estimated the value of 1,180 acres thought to be appropriate for the future park was valued at $2,263,000, and the value of an alternate 830-acre park was worth $1,660.00. [156] Additionally, these tourism-related commercial pressures on land prices (and, consequently, on land uses) accelerated the need to launch a public education campaign designed to acquaint residents with NPS policies pertaining to the nature of national parks and land uses the service considered compatible with its parks.

Since the word "park" conjured visions of baseball diamonds, picnic tables and other recreational structures in the minds of Guam residents (not unlike any town elsewhere in America), park planning made community involvement and public education absolutely crucial. Conflicting notions of the definition of park were exacerbated by the increased urbanization of Guam mentioned above. As more of the residents relocated to Agana, Tamuning, and Tumon, the demand for recreational and athletic uses of public land increased dramatically. The significance and centrality of the extended family traditionally enjoyed by long-time Guam citizens became increasingly jeopardized by the constraints of apartment and housing development living. This urbanization had particular significance for park planning since most of the urban growth occurred near and even adjacent to land being proposed for inclusion in the future park. So, the popularly perceived need for large, open areas for large social gatherings increased and was, in some respects, in conflict with the NPS notion of activities appropriate to battlefield parks. The mere suggestion of baseball diamonds or volleyball courts on the hollowed ground of Gettysburg would be enough to give NPS staffers heartburn.

These new and rapidly evolving political-economic dynamics argued strongly for rapid park planning and the rapid execution of the plan (including, most importantly an expedited land acquisition program). Unfortunately, the acquisition of land would prove to be an abiding irritant to those who would later manage the new park. They would find themselves trying to develop an embryonic park unit in an unsympathetic environment (some would characterize it as hostile).

In 1977 NPS revised its 1967 proposal. The 1977 plan identified the purpose of the proposed park as,

Provide an opportunity to tell the epic story of World War II in the Pacific from the attack on Pearl Harbor to war's end. Emphasize the battle of Guam as a classic example of the island-by-island fighting, which was an important factor in the prolonged struggle for control of the immense expanse of the Pacific Ocean, and how this affected the final outcome of the war. [157]

The proposal continued by setting forth the objectives of such a park:

Preserve important geographical and historical features in order to provide a setting with enough historic integrity to adequately tell the story of the battle for Guam.

Develop an interpretive program which will view the war and the battle for Guam as a part of history. This would include the particular interests and attitudes of both Japanese and Americans.

Manage historic and natural resources in order to retain, as nearly as is practical, the historic setting of those sites to be interpreted.

Provide only such developments as are needed to interpret and inform visitors. Provide access to important features and viewpoints, and permit adequate administration and management of the park.

Cooperate with the Government of Guam in assembling local artifacts of Japanese occupation and American invasions to the extent that they are necessary for interpretation.

Cooperate with Japanese historians in developing bicultural and bilingual interpretation.

The park planners did not ignore the social needs of residents. A picnic area was suggested for Gaan Point in the Agat Unit as well as day-use recreational facilities on Asan Point in the Asan Unit. [158] The park planners anticipated that both areas would be frequently used by island residents. Asan Point was also seen as offering a logical location for a regional park complex since it was a mere three miles from the urban center of Agana. The NPS park planners discussed the concept with the Government of Guam, who concurred. The planners envisioned that some use restrictions would be applied to the suggested regional park, including recreation being limited to day use; both construction and maintenance of facilities would be the responsibility of the Government of Guam; and all plans and designs would be reviewed by the Park Service in order to maintain historical integrity. [159]

In addition to economic, demographic, and political factors, natural conditions had to be considered as well. Earthquakes are very common on Guam; the island averages two each day strong enough to be sensed by measuring devices, and about two per month strong enough to be perceived by residents. Additionally, the island is battered usually twice each year by severe storms, and it is not unusual for one of those storms to be a typhoon. Under the heading of "Special Conditions," the 1977 NPS proposal included,

Structures and facilities must be designed to withstand typhoon winds.

Mildew in this warm, humid climate causes damage to supplies, equipment, records, etc. Air-conditioning is needed for protection of some storage areas, and dehumidifying devices may be required in other instances.

Flooding of shore areas results from wind-generated waves during intense storms, and low valleys may be flooded by heavy rainfall.

Erosion of soft volcanic soils is widespread and results from torrential rainfall on land where vegetation has been removed.

Corrosion of metal equipment and objects is accelerated by warmth, humidity, and the salt air.

The grassland savannas and tangantangan thickets are highly inflammable during the dry season. Unless checked, the resulting denuded land is then susceptible to severe erosion.

Steep terrain in certain areas within the park proposal, combined with the possibility of slumping and accelerated erosion of volcanic soils, suggests that particular care be taken in location and design of park developments. The bluffs above Asan and Piti beaches are particularly susceptible to such problems. [160]

Interpretive efforts would also present unusual challenges. It was becoming increasingly obvious throughout the 1970s that the majority of tourists vacationing on Guam would be Japanese. Therefore, the 1977 proposal concluded, interpretive efforts had to show sensitivity to both the Japanese as well as the Americans, and all interpretive material and signage had to be in Japanese as well as English. Park visitors had to be provided with the ability to view battlefields of Guam from both the American and Japanese viewpoints; therefore, landing beaches had to be viewable both from the beaches and from overlooking high ground. To that end the NPS planners envisioned an interpretive center on the rim of Fonte Plateau overlooking Asan Beach that would interpret the broader story of the War in the Pacific. Most interpretation of the battle for Guam was planned for the specific significant sites themselves, such as Asan Point, Adelup Point, Rizal Point, Gaan Point, and Bangi Island.

The unusual challenges created by the need to interpret the War in the Pacific for Japanese as well as American visitors necessarily expanded to include the need to identify and preserve Japanese as well as American artifacts. And, that identification and preservation effort would require soliciting the assistance of Japanese as well as American historians and preservations. As if the issues engendered by creating a national park in a remote territory under the shadow of lingering mistrust of the federal government were not enough to raise blood pressure, the requirement to create and foster a working partnership with a former world war enemy was divinely designed to add arrhythmia to the hypertension, particularly when that nation did not itself choose to interpret the history of a war it had lost. There were Japanese guns on Piti Point, tunnels and fortifications along the Matgue River, Japanese pill boxes at both Asan and Agat beaches, Japanese coconut log fortifications at Agat Beach, and literally tons of Japanese military artifacts mingled with American military artifacts strewn across the entire landscape. The Guam of 1941 simply no longer existed by August of 1944. What had been a coconut palm-laced tropical island embraced by a radiantly-hued barrier reef in 1941 was a smoking mound of treeless desolation littered with disabled tanks, amtracks, landing craft, mortar tubes, ammunition boxes and mile upon mile of unrecognizable, mangled steel in the fall of 1944. Telling the story of what happened would require investigations, research, analysis and the informed interpretation of both Japanese as well as American historians. Any story without the Japanese half could do no more than tell of an American amphibious landing. It would appear, however, that much of the more detailed planning, and certainly the implementing groundwork was left to the first superintendent, Thomas Stell Newman. Identification of possible World War II artifacts for acquisition, ground checking the park and its boundaries, coordination of day-to-day operation plans with local authorities, and coordination with other federal agencies as well as Japanese historians and government officials were all left open even after the legislation was passed. In an August 5, 1977, memorandum, Ruth G. Van Cleve, Director, Office of Territorial Affairs, reported that she understood the then-current NPS position to be to simply get Congress to pass the enabling legislation establishing the park, then come back later with a plan in hand to submit cost estimates for funding. [161]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

wapa/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 08-May-2005