|

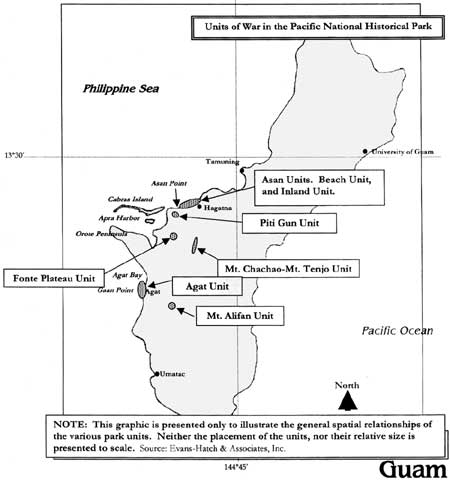

War in the Pacific

War in the Pacific National Historic Park An Administrative History |

|

Chapter 7:

LANDS

Introduction

Land acquisition for inclusion in the park has been one of the more complex issues NPS has dealt with from the park's inception until the present. The complexity of that acquisition can only be fully appreciated by understanding the historical context of land ownership and control on Guam. This chapter develops that history and traces the acquisition of park lands.

The acquisition and use of land has significantly affected the dynamics of the relationship between NPS and the residents of Guam. These dynamics assume their true significance when considered against the much broader historical backdrop of island land ownership and use generally. That history has been punctuated by what on occasion has appeared to be a cavalier attitude by various United States government agencies toward local ownership. The use of Guam by Spain and the United States as chattel to be used in negotiating the 1898 Paris Peace Treaty ending the Spanish-American War may well have engendered the United States Government's mind-set that has endured for the last one hundred years. The 677-page "Protocols" that were used by Spain and the United States as a preface to the treaty explaining their intent was very clear about local autonomy being a primary concern of both parties. However, the United States immediately transformed over a third of the island into a military installation, and generally treated the rest of Guam as its private property. A U.S. Navy officer was immediately appointed governor, and a pattern of military control of island affairs was established. That pattern continued for almost the next seventy years, and included: a June 27, 1930, order by the Naval governor of Guam (then Willis W. Bradley, Jr.) dividing the island into eight municipalities, [185] acquisition of 36 percent of the island land (claimed by the Guam legislature to have been acquired by fraud, deceit and cohesion); [186] the 1950 implementation of a "security clearance" program that prohibited civilian Guam residents from leaving or returning to Guam except through one of the island's military reservations; [187] and the prohibition against civilian residents of Guam growing agricultural crops for export (quite a blow since Guam residents had been exporting food for over three hundred years, starting with Magellan's arrival and resupply of his ships). Military control of civilian activities on the island was so pervasive that some legal scholars have concluded that Guam was under de facto martial law. [188] Table 9-1, below, presents a snapshot of land ownership changes that took place between 1950 and early 1953.

On October 15, 1977, the United States Congress finally responded to this pattern of land acquisition with the enactment of a statute empowering the District Court of Guam to hear claims alleging unfairness in government land acquisition. [189] The statute granted the court jurisdiction to review claims by persons or the heirs of persons from whom land was obtained between 1944 and 1963 by any means other than fair judicial condemnation proceedings. Fair proceedings were defined as proceedings where the land value was established by a contested hearing and employees and/or agents of the government did not engage in unconscionable conduct such as duress or undue influence. In a later application of this statute, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that Guam District Court should carefully reexamine the amount paid by the government where the initial taking of the land failed to include formal notice to the landowner that the hearing to establish the value of his land would take place whether he is there or not. [190]

| |||||||||||||||

| Figure 7-1. Land ownership on Guam in 1950 and 1952. Source: Manuel Guerrero, Director of Land Management, Government of Guam, Speech to the Guam Legislature, February 1, 1952. |

This seventy-plus-year pattern of United States military control engendered a deep sense of local resentment and mistrust. This was the political and social environment within which the park was born and nurtured. Unfortunately, accidents of history and politics added even greater misfortunes. The land originally included within the park boundaries established by the 1978 legislation that created the park as well as historically significant sites not included has resulted in protracted land acquisition negotiations, and misunderstandings that have caused a continuous sense of resentment.

The original land problems actually predated the park's creation by eight years. As far back as 1952 the United States Office of the Territories asked the Park Service's help in conducting a study of the recreational possibilities on Guam. In 1965 Park Service employees visited Guam at the request of the Governor of Guam [191] who had asked that NPS determine if any area on Guam had national significance — this study culminated in the park's creation being proposed. A copy of the NPS study proposing the creation was sent to Texas representative Richard C. White who had served on Guam during World War II and who would subsequently introduce federal legislation creating the park.

The reader will recall that during the mid- and late 1960s the United States was involved in the Vietnam War. Guam was used as a primary resupply location for Vietnam, including ammunition and other explosives. The U. S. Navy was increasingly concerned about handling explosives in a port facility it shared with civilian shipping. Consequently, the navy proposed that the United States exchange land with the civilian government of Guam. Cabras Island [192] appeared to be an ideal location for civilian port facilities, and at the time it was under the control of the Department of the Interior. Accordingly, the Department of the Interior sent the National Park Services' chief appraiser to Guam in October 1967 to assess the value to the property being considered for transfer to the Government of Guam. He concluded that the Cabras Island property was worth $540,000. The NPS appraiser was aware of the growing interest in creating a national historical park on Guam. He asked the Governor of Guam if Guam would be interested in exchanging land it owned that could be used for the park. The governor was very willing, and, in addition to the Government of Guam-owned land situated within the proposed park boundaries, offered to acquire privately-owned land situated within those boundaries and, in turn, convey them to the Park Service. Lands owned by the Government of Guam that were located within the proposed park boundaries were appraised at $1,085,000 (or double the value of the Cabras Island land). To make up this difference the Government of Guam identified other land owned by the United States on Guam that it would like to have. Unfortunately, that suggestion also failed to solve the equal-value problem since that additionally-identified land was valued at $821,900 resulting in a net of $276,900 owed to the United States by Guam. As partial payment of that difference, the Government of Guam agreed to acquire additional privately-owned land within the proposed park and convey it to the Park Service. The hope was that all private in-holdings within the park would ultimately be conveyed to the Park Service. By March of 1970 there was still 350 acres within the proposed park boundaries still privately owned.

On April 4, 1969, the U. S. Department of the Interior conveyed land it owned on Cabras Island to the Guam government to be used as civilian harbor facilities. As noted above, that April 4th conveyance included an agreement that the Government of Guam would subsequently convey land to the Department of the Interior for inclusion in a future War in the Pacific National Historical Park. On April 20, 1970, Carlos Camacho, then Governor of Guam made that conveyance by quitclaim deed. The deed conveyed 507 acres. [193] Between 1970 and 1972 the Government of Guam conveyed a total of 850.55 acres to the Department of the Interior for inclusion in the proposed War in the Pacific Park. [194] This was only part of only the first chapter of land acquisition activities that would continue well into the 1980s and beyond.

Even as Governor Camacho quitclaimed the 507 acres to the Department of the Interior, the department was looking for additional land. For example, in August 1969, Walter Hickel, then Secretary of the Interior, wrote to the Secretary of Defense asking the Navy to release Asan Point overlook and twenty-five acres on Marine Drive adjacent to what was then the Naval Hospital Annex to the Department of the Interior for inclusion in the future park. [195] (The Secretary of Defense agreed to release Asan Point, but indicated the Navy must retain the twenty-five acres adjacent the hospital annex.) [196]

And, meantime, Congressional involvement in land ownership continued. On October 5, 1975, Congress enacted the Submerged Lands Act. [197] This legislation conveyed submerged lands to the Government of Guam to be administered in trust for the people of Guam. The Act conveyed all submerged land from mean high tide to three miles off shore. Unfortunately, the rather long list of lands excepted from the statute (not conveyed to the Government of Guam) made the statute needlessly complex. The Act did not convey:

Oil, gas and other minerals; [198]

lands adjacent to United States property that was above mean high tide;

lands filled in or otherwise "reclaimed" by the United States Government prior to October 5, 1974;

submerged lands containing a structure or improvement built by the United States Government;

submerged lands previously identified by the president or Congress as having "sufficient scientific, scenic or historic value to warrant preservation;"

submerged lands identified by the president within 120 days after passage of the Act (120 days after October 5, 1974);

submerged lands under the control of any agency other than the Department of the Interior; and

all submerged land owned by persons other than the United States.

Additional problems were created when congress created the park in 1978 and the boundaries set for the park. The 1978 boundaries were not identical to the boundaries envisioned earlier, consequently, not all land previously conveyed to the Department of the Interior for inclusion in the park was within the boundaries set by the 1978 park-creation legislation. In fact, of the 850.55 acres conveyed by the Government of Guam to the Department of Interior only 521.29 acres were within the boundaries created by the 1978 park legislation. [199] This resulted in NPS having fee simple to some land exterior to park boundaries, and not having title to all the land situated within the park. [200]

Since the park's creation, NPS has struggled to acquire ownership of all land within the park boundaries and pending the acquisition of that ownership to somewhat ensure that the integrity of historically significant sites are not compromised. According to the draft of the Land Acquisition Plan prepared in 1979-80:

To prevent damage or adverse impacts to the Park's historical resources, and to properly develop and interpret the Park for the public, the National Park Service must completely control all lands and waters within the Park.

Leases, zoning restrictions, cooperative agreements, scenic easements, purchase of development rights, and all other protective controls of less than clear, fee-simple ownership of all lands and waters within the Park provide less than the best possible protection for these nationally significant Park resources. Therefore, fee-simple title to all lands and waters within the Park will be acquired by the National Park Service. [201]

The Park Service compiled a list of land within park boundaries that was privately owned, and prioritized that list, essentially establishing a chronologically sequenced land acquisition plan to be implemented parcel by parcel as congressional funding was received fiscal year by fiscal year. As is more fully explained below, the subtleties of United States government appropriations machinery was not completely appreciated by Guam residents who owned land scheduled to be acquired. There appears to have been a popular misconception that since the 1978 legislation that created the park approved a future $16 million funding for park development, that the entire $16 million was immediately available against which the park service could write checks. The second, required, legislative step of actually appropriating part or all of that money was simply not fully understood. It was not understood (nor made clear) that the $15 million was merely "authorized" for future appropriations; it was not actually appropriated, and, therefore, was simply not yet available.

Consequently, the mistrust of the United States government, nurtured by over sixty years of what was perceived as inappropriate taking of land, was broadened to include the park service and its efforts to create a War of the Pacific Park. Residents owning land within the park boundaries wanted either to sell their land at a reasonable price to the park service, sell their land to commercial developers, or to be free to develop their land themselves. Not only did they perceive that the park service was not immediately purchasing their land as they had expected, but the park service was taking steps to ensure the continued historical integrity of sites some of which were on these private parcels. These efforts to avoid or mitigate loss of historical integrity served to reduce the value of the privately-owned land since the efforts appeared to diminish development options for both the owners as well as prospective buyers. The United States' government's expressed intention to acquire nothing less than fee simple interests in the land, and the long history on Guam of land taking by condemnation actions seriously diminished the marketability and therefore the price of park in-holdings

|

| Figure 7-2. Antonio Borja Won Pat. Source: MARC, University of Guam. |

The struggle to protect the historical integrity of privately-held land within the park boundaries, taken together with the perception that the Park Service was not immediately purchasing the land as residents assumed would happen, resulted in Park Service struggles with both private landowners as well as agencies of the Government of Guam. For example on May 17, 1984, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation sent a letter to Leonard Paulino, Executive Director of the Guam Housing and Urban Renewal Authority. The letter complained of a proposed development to take place at the Asan Village Archaeological site. The Advisory Council strongly suggested that Guam government officials not permit the work to proceed without complying with the consultation process mandated by federal regulations (36 CFR, part 800.6(B)).

These struggles over land ownership and/or land control took place at a time that Guam was increasingly being perceived as Japan's Hawaii. The increasing influx of tourists from Japan (a short flight from Guam) increased pressures on the Government of Guam (and, indirectly, the Park Service) to permit development of a tourist-based economy, including high-rise hotels, restaurants, improved roads, more and larger retailing outlets, and recreational use of beaches and parks (including areas within the park). On July 23, 1979, then-superintendent Stell Newman sent a memorandum to NPS's western regional office in San Francisco. He stressed that NPS needed to expedite its purchase of in-holdings particularly in the Asan area since local businesses could not obtain expansion loans and land cannot be sold since it is scheduled to be taken by the government. [202] On March 4, 1982, Guam's congressman Antonio B. Won Pat testified before a hearing conducted by the Public Lands and National Park Subcommittee, complaining that the park remained nothing but a "park on paper," and has been waiting for three years for land acquisition and development funding. Congressman Won Pat observed that then-Secretary of the Interior James Watt's unwillingness to acquire new park lands was to blame. [203]

An October 1982 editorial appeared in the Guam newspaper reporting that as of that date only $500,000 had been appropriated for land purchases. The editorial quoted Stell Newman as expressing concern that President Reagan was trying to restrict further federal government land ownership. Newman is reported as concluding that a land protection plan originally scheduled to be prepared in 1984 should be prepared immediately. [See material above quoted from the subsequently prepared land protection plan.] Again in 1989 the National Park Service filed a briefing statement with the 101st Congress reporting that land acquisition was moving slowly. The NPS report also stated that land prices continued to go up in response to Japanese developers' land purchases and observed that private lands within park boundaries were prime land for development as tourist facilities. [204]

All of this inactivity was taking place after NPS had published it proposed Land Acquisition Plan in 1979, which stated, in part:

The Park's land acquisition program will be more easily understood if everyone knows the following basic goals of the program:

1. All private and public lands and waters within the boundaries of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park will be acquired by the National Park Service. Every private landowner must expect to be bought out as soon as funding permits. [Emphasis in the original.]

2. All private lands will be acquired in fee simple. Scenic easements, development rights, or other less than fee simple interests will not be acquired.

3. The maximum amount of funding possible will be requested by the Park each year so acquisition of all private lands will be swiftly completed.

4. The Department of the Navy and the Government of Guam will be asked to transfer all lands and waters under their jurisdiction within Park boundaries to the National Park Service as quickly as possible.

5. Insofar as possible, private lands will be acquired according to the following priority system.

The plan then listed the proposed order of land purchases, which was: a private residence on federal land in lot 260 of the Piti Unit, all private lands in Asan Beach Unit, followed by lands in Inland Asan Unit, followed in turn by lands in the Agat Unit, the Piti Guns Unit, lands in the Mt. Alifan Unit, and finally, lands situated in the Mt. Tenjo-Mt. Chachao Unit. [205]

A breakdown of land ownership within park boundaries in 1979 is presented in table 9-1, below. [For a breakdown of land ownership in 1979 by park unit, see Appendix 1.]

In January 1980, then-superintendent Stell Newman reported that there were over 230 acres of privately-owned land within the park and he perceived a realistic threat that incompatible development would occur on at least some of that acreage. He also indicated there were neither local nor federal protections against such development. Resistance to zoning controls and the ease with which owners could obtain variances neutralized local protections, and the lack of funding made federal protection unrealistic. [206]

Land issues also drew the Park Service into conflict with other federal agencies as well as local land owners. As was mentioned above, park boundaries included public lands administered by the Navy. The Park Service felt that those lands would be more appropriately administered by the Service. Additionally, there were areas outside the 1978 boundaries such as Nimitz Hill that NPS felt should be added to the park. The time was ripe for growth. The end of the United States' involvement in Vietnam resulted in the Navy's land requirements on Guam diminishing. Consequently, the Navy would declare a parcel it no longer needed as "excess," which would initiate a formal procedure where the General Services Administration (GSA) would become statutorily responsible for disposing of the parcel. GSA was required to notify other federal agencies of the availability of the land, and upon an expression of interest, the agency would take steps to convey the excess property to the new agency. This system had been in place for decades when the park was casting covetous gazes at additional land on Guam.

| ||||||||||||

| Figure 7-3. Ownership of land situated within park boundaries as of November 1979. Source: Land Acquisition Plan, Draft for Public Review, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, War in the Pacific National Historical Park, November 1979. |

The issue of an acquiring agency paying for the land was in a state of flux. There is no legal requirement that when "excess" land is conveyed from one federal agency to another federal agency that the acquiring agency must pay for it. A "nonreimburseable" transfer is not unusual. The decision regarding a "nonreimburseable" land transfer versus the receiving federal agency being required to pay for it is determined by the GSA with direction from the President's Office of Management and Budget. During the term of President Ronald Reagan (1981-89) all inter-agency land conveyances required the acquiring agency to pay the GSA fair market value for the property except in narrowly-defined cases. This Reagan-era proscription against nonreimburseable conveyances added a great deal of complexity to the park's development in the early 1980s. [207]

In late 1982, the Navy concluded that it no longer needed land it had been using on Nimitz Hill and declared the land "excess." This was the site of the Japanese command center during the initial American landing in July 1944; it provided an excellent view of the invasion beaches; and, it contained a rich assortment of plants native to Guam. The Park Service recognized the land's value, and in January 1983 the Secretary of the Interior notified Morris Udall, Chairman, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, that the Park Service would be making a minor boundary adjustment add these 36.52 acres on Nimitz Hill. [208] The Park Service also filed a formal request with GSA's 9th regional office asking that the land be conveyed to the Park Service at no cost to the service. [209] This request launched a protracted struggle between the Park Service and GSA that finally culminated in special legislation overriding the GSA-President position and authorizing a transfer of the land to the park at no cost. The struggle itself is informative.

The GSA's response to the March 2, 1983, NPS letter asking for a nonreimburseable conveyance of the Nimitz Hill property was to cite Executive Order 12348 as prohibiting the requested cost-free transfer and demanding $561,000 (which is what GSA had concluded was the fair market value of the land). Lowell White, Acting Director of the NPS Western Region notified the Director of the NPS Pacific Area of the GSA position. [210] In his letter, White observed that the Park Service didn't have the money at that time to purchase the land, but might in FY85 if the $1.5 million NPS appropriations request was approved. White also observed, however, that if the Park Service did purchase the Nimitz Hill land with the FY85 money, "it would have a drastic effect on the War in the Pacific Land Protection Plan's higher priority to purchase tracts along the invasion beaches fronting Marine Drive." [211] NPS renewed its request with the GSA, and this time David Stockman, Director of the Office of Management and Budget, Office of the President, responded and, again, reiterated that NPS would have to purchase the land for $561,000. [212]

The issue simmered for a while, and in May NPS' Regional Director for the Western Region sent a letter to GSA objecting to GSA's position. In his letter, the Regional Director argued that NPS funds would be depleted by having to purchase the Nimitz Hill parcels, resulting in its being unable to buy other land within the park owned by Guam residents. Were that to happen, the author of the letter argued, the federal government generally and the Park Service in particular would suffer an erosion of its already low popularity. Guam residents who owned land within the park had come to believe that NPS' purchase of their land was imminent. Additionally, if NPS failed to purchase that privately-owned land, continued the author, a number of those land owners would suffer financial hardships. [213]

During this same period, GSA and NPS were also debating Agat Bay Parcel number 2 (15.02 acres) which had also been declared excess by the Navy. NPS's August 10, 1983, letter to GSA asking that the Agat Bay parcel be transferred to NPS at no cost [214] went unanswered until NPS sent a second query six months later. [215] Only then did GSA respond by refusing to make a no-cost conveyance. [216] This GSA refusal was particularly poignant since the Agat Bay parcel at issue was listed on the Register of Historic Places. James Watt, Secretary of the Interior, also wrote to Gerald Carmen, Administrator of GSA, making the same pleas and arguments, but apparently to no avail. [217]

NPS was also pursuing the issue in Washington, D.C., as well as exchanging letters with GSA. In early 1984, NPS succeeded in having a bill introduced in the House of Representatives (H.B. 3519) that would have required the nonreimburseable transfer of any parcel declared "excess" by another federal agency to the Park Service if the parcel was located in a national park. Unfortunately, the bill died in committee and was not enacted. In October, however, NPS succeeded in having Congress add a provision to an appropriations measure conveying both the Nimitz Hill land as well as the Agat Bay parcel to NPS at no cost to NPS. [218] The General Services Administration conveyed Agat Bay parcel 2, and the Nimitz Hill land to the Park Service in early 1985. [219]

Park Lands Today

The park is comprised of seven separate, non-contiguous units on the central western side of the island. All park land is either on oceanfront property or on higher ground overlooking the beaches. Each unit is named for a landmark situated within the unit or close by.

1. Asan Beach Unit — 109 land acres, 445 acres off shore: Generally an area of sandy beach ranging from fifteen to thirty feet wide. The offshore area is within the reef and extends up to 1,000 feet off the beach. Water depth is from one to four feet with multiple coral formations. The boundaries of this unit encompass private homes and small businesses along the shoreline. There is an elementary school near the unit. A Navy hospital annex was built here in the 1950s and continued to be used until the late 1960s, with some of the buildings continuing in use during the Vietnam War. Although the buildings are now gone (with one exception), building foundations, and the remnants of paved roads remain. Historical cultural features pertaining to World War II are limited to Japanese defense structures, including gun emplacements, caves, and approximately ten pillboxes. Some American battle equipment is reported to be offshore.

|

| Figure 7-4. Asan Beach Unit entrance sign. Photo by Evans-Hatch & Associates, 2003. |

2 and 3. Asan Inland Unit, and Asan Beach Unit — 593 combined acres: These two combined units comprises the largest single geographical park unit (they are separated by a road). The Inland Unit occupies rugged topography situated between the coast highway and uplands that rise to 500 feet above sea level. Nimitz Hill, the site of Admiral Nimitz's headquarters for the pacific fleet, is situated in this unit. A major battle was fought between American and Japanese forces in 1944 when the United States retook the island from Japanese occupation. There are remains of Japanese defensive fortifications at both the north and south ends of the unit, including pillboxes, various foundations, and a 75mm mounted gun. Both the terrain and the flora in this unit remain much as they were during the Second World War.

4. Piti Guns Unit — 24 acres: The smallest unit, it lies in hilly terrain immediately above the village of Piti. Three Japanese coastal defense guns remain in situ; however, they have been dislodged from their mountings by typhoons. The guns are situated on a westward-facing slope with an excellent view of the lagoon and Pacific Ocean. A dense stand of mahogany dates from a prewar agricultural experiment station situated on the site.

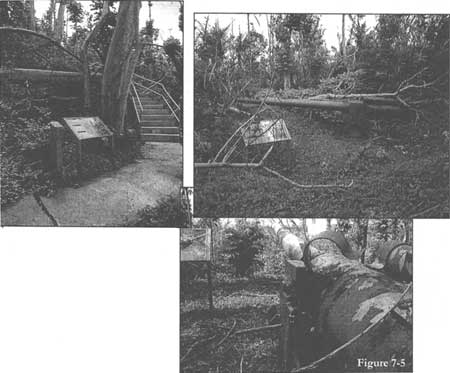

|

| Figure 7-5. Clockwise from upper left: interpretive sign at the base of stairs leading up to the gun emplacement; one of the guns with an interpretive sign; looking down one of the guns toward the Philippine Sea. Note damage from the super typhoon of 2003. Source: Evans-Hatch & Associates, Inc. |

5. Mt. Tenjo — Mt. Chachao Unit — 45 acres: This unit is comprised of a vary narrow strip of land running along the ridge that connects Mt. Tenjo and Mt. Chachao and affords excellent views of both Agat and Apra harbor areas.

6. Mt. Alifan Unit — 158 acres: The unit lies on the western slopes of Mt. Alifan immediately adjacent to the communities of Santa Rita and Agat. The terrain is hilly dominated by open grass lands on the lower areas and dense jungle growth on the upper slopes.

7. Agat Unit — 38 land acres; 557 acres in the water: The unit's land is comprised of small, not always contiguous parcels between the coastal highway and the shore. The low-lying shoreline is accented by coral outcroppings rising no more than twenty feet above water level at high tide, and two small islets, Alutom and Bangi. The water portion of this unit is a one- to four-foot-deep lagoon fringed by a barrier reef. Historic remains dating from the Second World War include caves, bunkers, and more than ten pillboxes. The town of Agat is immediately adjacent to the unit, and the park is extensively used by local residents.

|

| Figure 7-6. Above: one of the Piti Japanese guns off its mount; trail leading to Piti gun emplacement. Source: Evans-Hatch & Associates, Inc. |

|

| Figure 7-7. Top: Signage at Agat Unit. Entrance to Gaan Point, right; entrance to Apaca Point, lower. (Both are part of the Agat Unit). Bottom: Beach at Gaan Point; Japanese defense fortifications at Gaan Point. Source: Evans-Hatch & Associates, Inc. |

|

| Figure 7-8. Gaan Point. Clockwise, from upper left: looking southwest at World War II guns; looking west, bunker mound with tourists approaching guns; looking northeast from the top of the bunker mound; looking north from the bunker mound, the bunker's landward opening is in the middle ground. Source: Evans-Hatch & Associates, Inc. |

|

| Figure 7-9. Apaca Point. Clockwise, from upper left: Picnic area looking west toward lagoon; tourist reading interpretive sign on beach side of picnic tables, looking southwest; sidewalk and interpretive sign, looking west toward the lagoon; distant view of picnic area, looking west toward lagoon. Source: Evans-Hatch & Associates, Inc. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

wapa/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 08-May-2005