|

War in the Pacific

Asan and Agat Invasion Beaches Cultural Landscapes Inventory |

|

| PART 3a |

ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION

Summary

Seven landscape characteristics assessed for this report have retained high degrees of integrity and contribute to the historic character of the landscape. Archeology, buildings and structures, cluster arrangement, natural systems and features, spatial organization, topography, and views and vistas all played an important role in the historic events and remain in context on the landscape.

The defense structures in the archeology section fall into the category of archeological sites and are considered significant and contribute to the historic scene of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

The predominant buildings and structures found at the War in the Pacific National Historical Park are Japanese defense structures. These structures played a significant role in the history of the U.S. Military effort to recapture Guam. Since the 1940s, these structures have undergone weathering, however, they have retained integrity and are considered significant and contribute to the historic scene.

The cluster arrangement of Japanese defense positions retains integrity and is contributing to the historic scene of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

Natural systems and features played a significant role during the U.S. Military effort in Guam. Most notable, within the two beach units are five coral outcrops. Adelup Point and Asan Point flank both sides of Asan Beach, and Apaca and Bangi points flank Agat Beach with Ga'an Point located centrally in Agat Beach Unit. The Japanese focused on the enhancements of the natural caves and crevices. Defensive pillboxes, bunkers, and gun emplacements were clustered within these outcroppings and became strongholds for the Japanese defense. The spatial organization, of the historic and existing landscape, shows a clustering and clear relationship between the buildings and structures and the natural topography. Vegetation within both beach units has also contributes to the historic integrity. The five coral outcroppings retain the patches of limestone forests that hid Japanese defense structures from aerial and ground reconnaissance. These structures then became strongholds and impacted offensive landing and maneuvers. Coconut groves along the beaches have changed in regards to their densities and no longer retain integrity.

The spatial organization of the Asan and Agat battlefields were most influenced by the natural terrain. Both the offensive and defensive military strategies were planned around the existing landscape and the five limestone outcrops on Asan and Agat beaches. The spatial relationship between the coral reefs, beaches and coastal plains and the organization of the U.S. and Japanese military strategies that influenced the outcome of the recapture of Guam is still intact and contributing to the historic scene. The spatial relationship of the Japanese defense structures in the five coral outcroppings (Adelup, Asan, Apaca, Ga'an and Bangi points) are also still intact and contribute to the historic scene of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

Topography played a crucial role in the American offensive and Japanese defensive strategy. Changes to the topography since the period of significance have been minimal. As a result, topography in Asan and Agat beach units continues to remain significant and contributing to the historic scene of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

The historically significant views that were crucial in the military strategy and actual battle were longrange views from the sea and beaches toward high ground and vice-versa, short-range views from the sea toward the beaches and vice-versa, and short-range views in between the five points (Adelup, Asan, Apaca, Ga'an and Bangi). These views influenced the location of communication stations, gun emplacements, and other military strategies. Today, these views are still clear and contribute to the historic integrity of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

The seven characteristics that retain a high degree of historic integrity and contribute to the historic significance of Asan and Agat invasion beaches are archeology, buildings and structures, cluster arrangement, natural systems and features, spatial organization, topography, and views and vistas. All of these characteristics have played a significant role in and contribute to the historic events of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

Landscape Characteristics And Features

Archeological Sites

The arrival of the first inhabitants of the Mariana Islands occurred about 3,000 years ago, as documented by archaeological excavations in Saipan. Present evidence does not support prehistoric occupation of Guam prior to about 2,500 to 3,000 years ago (Olmo 1995:13).

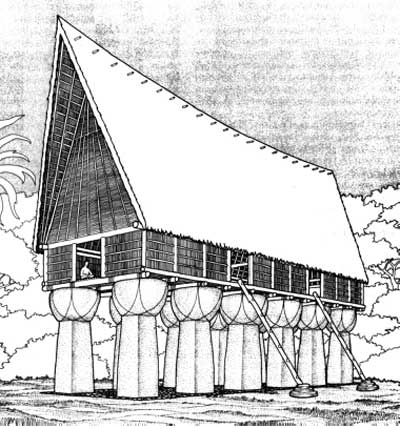

Guam's prehistoric record is divided into two broad periods spanning the beginning of human settlement in the Mariana Islands (ca.1000 B.C. through European contact in A.D. 1521) the Pre-Latte and the Latte. The Latte period began ca. A.D. 800. Latte refers to stone columns found at many prehistoric living sites. They are hand hewn from nearby sources of coral, limestone, and volcanic rock. The columns are composed of two parts, an upright shaft and a hemispherical cap. They are usually found in groups, occurring in parallel rows, and are believed to be foundations for the floor beams of wooden houses. These houses most likely were those of high status individuals of the community (Olmo 1995:14-15).

The Latte sites were for permanent habitation (as opposed to temporary habitation sites associated with the northern limestone forests of Guam). Desirable features included fertile soils for agriculture, and productive reef-lagoon habitats for fishing (Hunter-Anderson 1989:7). The Agat coastal area of Guam was characterized as having geographic attributes that offered desirable habitation sites during the Latte period.

Pre-Latte sites indicate that the population, during initial phase of immigration and settlement, was located along coastal areas. The Hunter-Anderson study, done for the Small Boat Harbor at Agat, found no surface evidence of cultural remains. However, auger tests performed by Watanabe in 1986 indicated that pre-Latte subsurface remains might be yielded at Agat Beach. The "coral and sand beach overlie a substantial older intact alluvial clay deposit with localized evidence of prehistoric/early historic cultural remains" (Watanabe 1986:2). These remains may be non-residential but is a new site-type offering a model of prehistoric farming on Guam. The site may also offer recognition of a major geological event, during prehistoric human occupation on Guam, which caused the massive erosion evident in the deep alluvium at the Agat Beach study site (Hunter-Anderson 1989:27). The Small Boat Harbor study area is just south of the southernmost park boundary at Bangi Point. Although it is not within the boundaries, similar subsurface features are possible, if not probable, within the Agat Beach Unit.

Guam's historic period can be divided into four occupational periods The Spanish Period (A.D. 1664-1898), the First American Period (1898-1941), the Japanese Occupation (1941-1944), and the Second American Period (1944).

The Spanish Colonization period was well documented by Spanish government and military representatives, missionaries, and expeditionaries (Olmo 1995:16). Little material remains are present from the 234 years of Spanish occupation (Reed 1952:101). Many journals and written sources indicate that missionary efforts and Spanish settlement from 1668 mostly centered on Agana. However, the normal processes of time and vegetation growth along with the effects of typhoons and earthquakes have taken their toll on physical remains. But most destructive was the pre-bombing and battle of 1944. Archeological research identifies ruins of stone bridges and cathedrals to the north and south of NPS boundaries. No surface features from this period remain within Asan or Agat beach units. No sub-surface studies have been conducted within Asan or Agat beach units.

The First American Period spans 43 years, from 1898, when America acquired Guam as part of the settlement after the Spanish American War, until 1941 when the Japanese invaded. During this period, improvements to infrastructure included better roads, new schools and expansion of the water system (Olmo 1995:17). The Asan Beach Unit land use varied from detention camps to a Navy hospital throughout the 43 years. The Japanese destroyed many American buildings after taking control of the island in 1941.

During the Japanese occupation of Guam, little structural improvements were made. During the prebombing and battle of July 21 — August 10, 1944, any remaining structures within the Asan or Agat beach units were destroyed. Today, the beach units of Asan and Agat contain only Japanese defense structures. These include gun positions, bunkers, caves, and an offshore latrine (Olmo 1995:75).

Archeological studies have been done for Mt. Chachao (Olmo 1983), the Small Boat Harbor, Agat, (Hunter-Anderson 1989) and overviews of Guam (Reed 1952). Surveys done through the 1950s have focused primarily on the Pre-Latte and Latte Periods. Although no specific archeological studies have been done on Asan or Agat beach units, archeological investigations could yield subsurface information from WWII, prewar, Spanish, Latte, and Pre-Latte periods.

Defense Structures

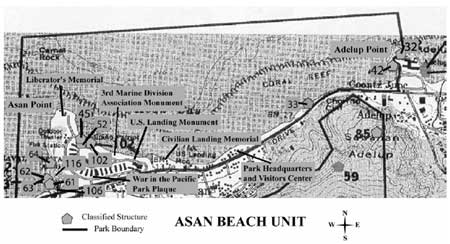

When war looked imminent, the Japanese realized that they needed to plan a strategy and build defense structures. The decision to reinforce their position on the island had come so late (March 1944) that they had less than three months to prepare. General Takashina and his subordinates felt that between the lack of Japanese troops available, and the limited time period given to them for preparation, their situation was hopeless. Nevertheless, they began to build with the forced labor of the Chamorro people. There were critical shortages of cement, reinforcing steel, lumber, and a wide range of needed hardware, which limited the kinds of fortification that could be built (Gailey 1988:40). The defense structures included pillboxes, cave bunkers, tunnels, and gun emplacements. These structures varied from well-built concrete faced enclosures with multiple gun openings to crude and hurried concrete caps on holes dug in the dirt. However, some of these defense structures have lost integrity and are now contributing as archeological sites. These site numbers are 061, 062, 063, 064, 98, 102, 116, 032, 033, 023, 024 and 9 (see classified structure map).

Japanese Emplacement (LCS 061)

This reinforced concrete structure has one front wall embrasure and two

side firing ports. The concrete extends back 7-feet into the west side

of Asan Point. It takes advantage of a natural crevice between free

standing boulders and the cliff wall to hide the entry. The field of

fire was towards Cabre Island.

Japanese Emplacement (LCS 062)

This rectangular-shaped structure has a combination rock and concrete

front wall and roof that enclose a natural crevice. The crevice extends

into the cliff from the back of the enclosure. There is a 5' diameter

steel gun base behind the front concrete wall.

Asan Point Japanese Gun Emplacement (LCS 064)

This pillbox is built into the western rock cliff of Asan Point with low

angled concrete walls around the front opening. A metal gun base,

possibly for a 20 centimeter coastal gun, is mounted into the concrete

floor behind the front wall. The rear portion extends into two caves and

a third cave is accessible from a side trench.

Asan Point Japanese Defensive Ridge Line (LCS 98)

Structure was not located after Supertyphoon Paka in 1998 or during 2000

List of Classified Structures (LCS) fieldwork.

Asan Beach, Offshore Japanese Pillbox (LCS 102)

Reinforced concrete pillbox is overturned and located approximately

40-feet offshore of Asan Beach. It has one embrasure and one rifle slit.

It is not clear if the structure was initially located offshore and then

overturned, or it was originally sited on the beach and later discarded

offshore. No foundation site is apparent on the beach.

Double Gun Emplacements on Asan Ridge (LCS 116)

Two concrete structures are set into hill with only 2-3 feet openings

above ground. These structures served as either fire control station or

rifle/gun emplacements, one overlooking Piti, the other Asan Beach.

Adelup Point Cave and Foxhole (LCS 032)

This Japanese defensive structure built into the coral outcropping known

as Adelup Point within the Asan Beach Unit.

Chorrito Cliff Seawall along Asan Beach (LCS 033)

This rock and concrete wall was once 400' long and is now only 75-feet

long. It is a concrete wall atop a stonewall base. It is 40-inches high

and L-shaped. The stone base was a remnant feature of the Spanish

occupation (1800-1900) that was modified by the U.S. Military. It was

intended to protect the new highway, built in 1944, against storm

damage. Because it is now less than a quarter of its original length and

broken in two places, it does not retain structural integrity. However,

it is an important feature from the historic period and does contribute

to the character of the cultural landscape. This feature is located on

property owned by the Government of Guam.

Ga'an Point Japanese Bunker (LCS 024)

Located near Ga'an Point, this reinforced concrete pillbox is L-shaped

and built between two rock escarpments. A smaller observation pillbox is

located on the escarpent above with a connecting metal communication

tube.

Ga'an Point Bunker (LCS 023)

This rectangular reinforced concrete pillbox is built into a limestone

escarpment. It housed a 75mm 94 type gun with a field of fired over Agat

Beach that caused havoc on U.S. Marines and landing craft on WDay until

American troops captured it.

Ga'an Point Japanese Bunker (LCS 9)

This Japanese defense structure housed a 75mm gun with a field of fire

directed across Agat Beach. The 20" thick walls are made of reinforced

concrete and the structure has an irregular L-shaped plan.

Summary

Considering the location of pre-Latte habitation sites along coastal areas, and the subsequent history of Spanish, Japanese, and American occupation, it can be assumed that Asan and Agat beach units would likely yield subsurface archeological information. Defense structures are contibuting as archeological sites and are considered significant to the historic scene at the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

Illustration of a 'Big House' on latte stones associated with the

precontact Chamorro structures (Drawing from Morgan 1988, in Rogers

1995:35).

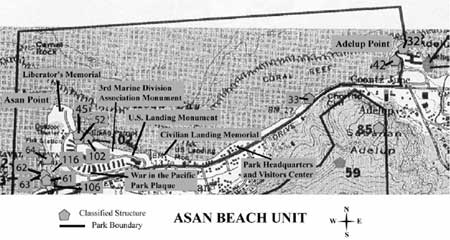

Map showing location of classified structures on the Asan Beach Unit

(CLI Team/PISO/2003).

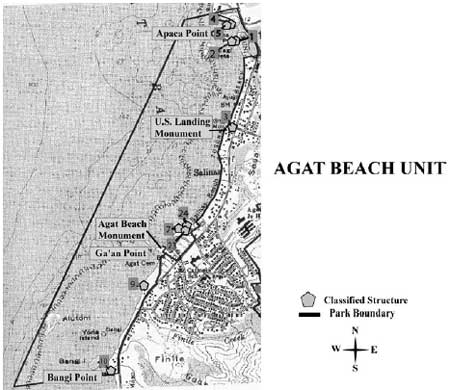

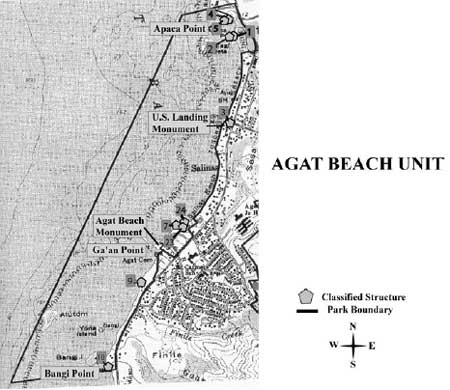

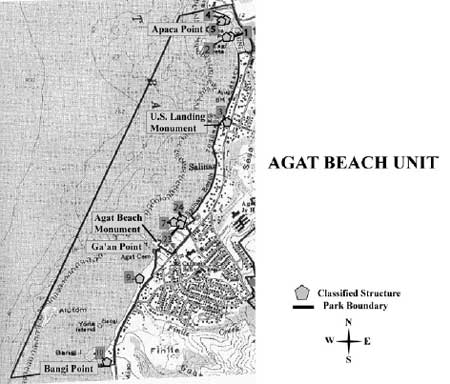

Map showing classified structures on the Agat Beach Unit (CLI

Team/PISO/2003).

Contemporary photo of the remains of the seawall at the Asan Beach

Unit (LCS 2000).

Contemporary photo of the offshore Japanese pillbox (LCS 2000).

Contemporary photo of the Asan Point gun emplacement with a

reinforced metal support frame (LCS 2000).

Buildings and Structures

Pre-war Chamorro houses in Asan and Agat were wood and thatch construction. Only about a fourth of the homes had a cement foundation. Very few homes were "built of masonry with corrugated sheet-iron roofs" (Jennison-Nolan 1979). Pre-War bombing, invasion, and occupation episodes eliminated almost all pre-war buildings and structures throughout Guam, and especially at the Asan and Agat beach units. The only structures remaining on the landscape are associated with the war. These are predominantly defensive structures built by the Japanese.

Defense Structures

When war looked imminent, the Japanese realized that they needed to plan a strategy and build defense structures. The decision to reinforce their position on the island had come so late (March 1944) that they had less than three months to prepare. General Takashina and his subordinates felt that between the lack of Japanese troops available, and the limited time period given to them for preparation, their situation was hopeless. Nevertheless, they began to build with the forced labor of the Chamorro people. There were critical shortages of cement, reinforcing steel, lumber, and a wide range of needed hardware, which limited the kinds of fortification that could be built (Gailey 1988:40). The defense structures included pillboxes, cave bunkers, tunnels, and gun emplacements. These structures varied from well-built concrete faced enclosures with multiple gun openings to crude and hurried concrete caps on holes dug in the dirt.

All of the structures within the Asan and Agat beach units take advantage of the natural terrain. Most structures are found in the five coastal outcrops that provided natural caves and crevices. These were enlarged and made to connect through a series of tunnels. Reinforced concrete and/or stone walls were added for support and cover the gun bases mounted inside. Heavy combat obliterated many of these defense structures, however many still remain within Asan and Agat beach areas. Very few structures were built upon the beaches. Only one remains offshore of Asan Beach, possibly discarded when American troops began organizing the beaches as supply bases.

Some ingenious features or design techniques were added to structures. Some pillbox/caves had interior passages that extended from shoreline to ridge top. These were advantageous for attacking the first wave of American troops coming from ship to shore. Then, the Japanese would retreat through the caves up to the ridge top. After the cave appeared to be abandoned, and American troops felt secure ashore, the Japanese could return to the lower position and attack from behind. One pillbox was found to have a grenade-proof air vent that diverted any grenade through a shoot to deposit it outside of the pillbox. Other structures, clearly seen from troops advancing towards the shore, were thought to have been deliberately obvious to distract attention away from well-camouflaged strongholds.

Many of the historic Japanese defense structures built in 1944 are in a state of deterioration from various factors including weather, erosion, vegetation, visitation, vandalism, structural deterioration, or inappropriate maintenance techniques. Vegetative root systems cause expansive pressure on cement structures and can cause the disconnection between stone and mortar. The cracks created from roots allow for water to penetrate into structures resulting in the leaching of limestone compromising strength and integrity of the structure. Structural assessments of these structures were recorded in three NPS reports: The List of Classified Structures (LCS) 1978-2000, the Emergency Super-Typhoon PAKA Report 1998, WAPA Historic Structure Storm Damage:1998, and the Cultural Resource Assessment of Historic WWII Sites 2003. As an aggregate, all of the structures contribute to the historic character of the cultural landscape. However, some structures lack individual physical integrity, or have been modified in a manner that effects integrity (such as the use of steel material for structural reinforcements because of roofs caving in). These structures are listed within the Archeological Section of this document. The remaining structures that retain integrity are listed in this section and remain a contributing feature to this historic scene.

Asan Beach Unit from Asan Point to Adelup Point

The defense structures and tunnels are found on the east and west side

of Asan Ridge as well as Adelup Point.

Adelup Point (LCS 042)

This Japanese defensive structures in the coral outcropping known as

Adelup Point with in the Asan Beach Unit.

Japanese Tunnel at Asan Point Ridgeline (LCS 106)

Sole surviving Japanese defense structure on east side of Asan Point,

along the ridgeline. Only structure within the park built by forced

Chamorro labor. Exact location

1961 Mabini Monument (LCS 045)

This 1961 monument is a coral obelisk set on two concrete steps atop a

larger circular concrete pad. There are three concrete benches in a

circular pattern around the monument and concrete bollards with a chain.

It commemorates Apolinario Mabini, the Prime Minister and Secretary of

Foreign Affairs of the first Philippine Republic. He refused to pledge

allegiance to the American Flag, when America acquired the Philippines

after defeating the Spanish in 1889. He was banished to Guam in 1901,

landing on the beach at the site of the monument where he was retained

until he returned to the Philippines in 1903.

1964 Mabini Monument (LCS 052)

This monument sits next to LCS 045 (another Mabini monument). It also

has a three-stepped concrete base with an exposed aggregate pillar and a

metal plaque with text and the seal of the Philippine Historical

Committee.

3rd Marine Division Association Monument (LCS MRKR1)

Cast bronze plaque set on cube of concrete (4'x3'x3' high). It has a

low, flat rectangular exposed aggregate concrete base and is painted

white.

War in the Pacific Park Plaque (LCS MRKR2)

Plaque at entry to Asan Beach Unit commemorating the "courage and

sacrifice of submariners whose heroism during WWII contributed

significantly to the liberation of the Pacific." Cast bronze plaque on

raised, beveled concrete mount, set in front of a mounted MD 14 MOD5

torpedo.

U.S. Landing Monument (LCS MRKR3)

Located where 21st U.S. Marines landed on Asan Beach. Commemorates the

1944 American liberation of Guam, one of the most intense and costliest

battles of the Pacific. Gives history of battle, lists commanders and

dedicates the monument to all American dead. Dedicated by Gen. Lemuel C.

Sherherd Jr. White rectangular monolith set on square base. Four brass

plaques are attached. A 3D cast replica of Marine insignia is located on

the top and its painted.

Civilian Landing Memorial (LCS MRKR4)

Commemorates landing of U.S. Forces in the 1944 liberation of Guam and

is the site of annual celebration commemorating the event. Installed by

American Legion. Tripartite wall with entry walkway. Engraved, upright

artillery round set on center section. Separate flagstaff 50' south set

on stepped square white concrete base w/ 3 levels. Asan Beach unit,

located east of mouth of Asan River.

Liberator's Memorial (Not on LCS)

This six-sided structure, approximately 6-foot high, is set on six-sided

platform of three painted aggregate steps. Each side is dedicated to a

division of the Armed Forces, including the Navy and Navy Seabees, Army

Air Corps, Coast Guard, U.S. Army, 3rd Marine Division, and the 1st

Provisional Marine Brigade. This memorial commemorated the 50th

Anniversary of the battle for the Liberation of Guam. Three small

benches and a few ornamental plants surround it. Both the Guam and

American flag fly over this commemorative memorial.

These monuments, plaques, and memorials listed above were built after the period of significance and are therefore non-contributing to the historic landscape.

Agat Beach from Bangi Point to Apaca Point, including Ga'an Point

The Agat Beach Unit holds Japanese defense structures, one American

built latrine, and a monument. Contemporary site structures include one

restroom, picnic tables and pavilions, bar-b-que grills, and

interpretive exhibits including a coastal gun and wayside exhibits.

There is also a three-flag memorial flying an American, Government of

Guam, and the Japanese flag.

Apaca Point Japanese Bunker with Tunnel (LCS 001)

This pillbox is located on the southeast corner of Apaca Point with the

entrance on the land-ward side leading down a 170-meter tunnel to the

pillbox that faces south. It is constructed of reinforced concrete built

into the rock outcropping with a rubble-in-concrete exterior for

camouflage. It most likely held a 40cm gun with the field of fire over

the beach inner reef, and a rifle range over the beach. It features an

ingenious grenade proof air vent that will reroute any grenade dropped

into it, to the ground outside of the pillbox.

Apaca Point Japanese Bunker (LCS 002)

Pillbox of reinforced concrete, built within natural limestone crevices,

with two firing ports that face the beach. The guns were probably 40 to

75 mm and the firing ports are not embrasure style. This pillbox is

inaccessible at high tide.

Apaca Point Japanese Tunnel (LCS 103)

Japanese coastal defense system tunnel connecting LCS 001 and LCS 002

together. The tunnel is enclosed by a concrete and rock roof.

Agat Japanese Cave (LCS 004)

This cave was either man-made or was a natural cave enlarged to

accommodate two to three men. The opening is approximately 4' wide. It

may have been used as a gun emplacement due to its strategic position

along the beach.

Rizal Point Japanese Bunker (LCS 005)

This bunker is located on southeast corner of Rizal Point in Agat Unit.

This defense structure was build as part of the Japanese coastal defense

units and was partially damaged during the U.S. naval shelling.

Ga'an Point Latrine Foundation (LCS 007)

Last structure of the tent city that U.S. Military forces built to house

Guamanian refugees liberated in Battle of Guam. There had been a line of

latrines with concrete foundations and frame superstructures in water,

connected to camp by walkway. This rectangular structure is located in

the ocean about 15 feet offshore.

Bangi Point Japanese Pillbox (LCS 10)

This reinforced concrete pillbox is located at the water's edge. The

pillbox has two firing embrasures and a rifle slit, and the roof is

embedded to act as camouflage. The entry on the rear side has protective

wing walls. Fields of fire to the north and south along the beach.

Agat Beach Monument (not on LCS)

This monument is located at Ga'an Point, within the Agat Beach Unit. It

includes a monument of three flags: American, Chammoro and Japanese.

U.S. Landing Monument (not on LCS)

This monument is located south of Apaca Point. This monument consists of

a three part concrete base with a large ammunition shell with a metal

flag pole mounted behind the shell.

Summary

Initial intents of commemorative monuments were to be separate from the actual historical park. As stated in the 1967 master plan proposal to Congress, for the War in the Pacific National Park: "There is no conflict between the proposal for a memorial, which would involve a site in Agana, near the Government House, and the historical park, which would involve lands primarily at Asan and Agat" (DOI 1967:1). Today, these monuments associated with the Asan and Agat beach landscapes do commemorate the events, but they are not from the period of significance, and are therefore noncontributing features of the cultural landscape.

Sixty years after the liberation of Guam, battlefield structures remain within the Asan and Agat beach units. Although all of the structures listed in this section have undergone weathering since the 1940's, they are still considered to have integrity and are significant and contributing to the historic scene of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

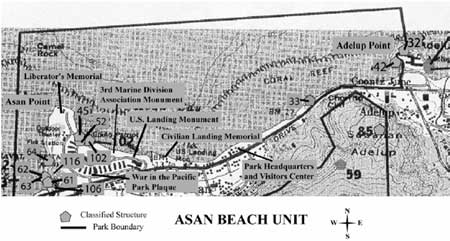

Map showing classified structures on the Asan Beach Unit (CLI

Team/PISO/2003).

Map showing classified structure locations on the Agat Beach Unit

(CLI Team/PISO/2003).

Contemporary photo of Adelup Point cave located on the northern end

of the Asan Beach Unit (CLI Team/PISO/2003).

Contemporary photo of the Bangi Point Japanese pillbox (NPS

2003).

Contemporary photo of the Apaca Point Japanese bunker located at the

northern end of Agat Beach Unit (CLI Team/PISO/2003).

Contemporary photo of the Ga'an Point Japanese bunker located in the

central part of the Agat Beach Unit (CLI Team/PISO/2003).

Contemporary photo of the 1961 Mabini Monument located on the Asan

Beach Unit (LCS 2000).

Contemporary photo of the 1964 Mabini Monument located on the Asan

Beach Unit (LCS 2000).

| Characteristic Feature |

Type Of Contribution |

LCS Structure Name |

IDLCS Number |

Structure Number |

| Adelup Point Cave | Contributing | Adelup Point Cave | 021202 | 042 |

| Agat Japanese Cave | Contributing | Agat Japanese Cave | 101677 | 004 |

| Apaca Point Japanese Bunker | Contributing | Apaca Point Japanese Bunker | 021191 | 002 |

| Apaca Point Japanese Bunker with Tunnel | Contributing | Apaca Point Japanese Bunker With Tunnel | 021190 | 001 |

| Apaca Point Japanese Tunnel | Contributing | Apaca Point Japanese Tunnel | 101698 | 103 |

| Bangi Point Japanese Pillbox | Contributing | Bangi Point Japanese Pillbox | 101679 | 10 |

| Ga'an Point Latrine Foundation | Contributing | Ga'an Point Latrine Foundation | 056572 | 007 |

| Japanese Tunnel at Asan Point | Contributing | Japanese Tunnel | 056579 | 106 |

| Rizal Point Japanese Bunker (Agat Beach) | Contributing | Rizal Point Japanese Bunker | 021192 | 005 |

| 1961 Mabini Monument at Asan Beach | Non-Contributing | 1961 Mabini Monument | 021203 | 045 |

| 1964 Mabini Monument at Asan Beach | Non-Contributing | 1964 Mabini Monument | 021204 | 052 |

| 3rd Marine Division Association Monument | Non-Contributing | 3rd Marine Division Association Monument | 056573 | MRKR1 |

| Agat Beach Monument | Non-Contributing | |||

| Civilian Landing Memorial | Non-Contributing | Civilian Landing Memorial | 056576 | MRKR4 |

| Liberator's Memorial | Non-Contributing | |||

| U.S. Landing Monument (Agat Beach Unit) | Non-Contributing | |||

| U.S. Landing Monument (Asan Beach Unit) | Non-Contributing | U.S. Landing Monument | 056575 | MRKR3 |

| War in the Pacific Park Plaque | Non-Contributing | War In The Pacific Park Plaque | 056574 | MRKR2 |

Cluster Arrangement

The U.S. Military pre-invasion bombardment varified for the Japanese that American forces would land and invade from Asan and Agat beaches (USMC 1998:14). Therefore, their arrangement of defensive positions clustered around the Orote Peninsula and the ridgelines and limestone outcrops that overlooked Asan and Agat beaches.

These outcroppings, within the Asan and Agat beach areas, extended out into the bays providing perfect cover for pillboxes, caves, and gun emplacements. The pillboxes at the ridge-tops offered alternative views and positions. Caves extending from ridge-tops to the beach below allowed Japanese soldiers to position along the beach during the landing phase then retreat up to the ridgeline for perfect sniping positions.

Today, most of the remaining structures are Japanese defense structures clustered within these ridge points; Bangi Point, Ga'an Point, and Apaca Point in the Agat Beach area, and Asan Point and Adelup Point in the Asan Beach area.

The cluster arrangement of structures clearly retains the historic integrity of strategic positioning in relation to the natural terrain and to each other.

Interpretive displays and signs are scattered throughout both beach units. Some gun emplacements are interpreted in original positions. Signs explaining the Japanese strongholds are also placed in relationship to site.

Monuments and associated interpretive signs are scattered throughout both park units. Some are associated with and commemorative of WWII. Others are not. There is no specific clustering or formal arrangement of monuments in either Asan or Agat beach units.

Cluster arrangement of the Japanese defense positions retains integrity and is contributing to the historic scene of the War in the Pacific National Historical Park.

Map showing location of classified structures on the Asan Beach Unit

(NPS 1998).

Map showing location of classified structures on the Agat Beach Unit

(NPS 1998).

Contemporary photo of one of a cluster of defense structures at Asan

Point (CLI Team/PISO/2001).

Contemporary photo of a cave at Apaca Pont, one of a cluster of

defense structures on the Agat Beach Unit (CLI Team/PISO/2001).

Contemporary photo of a defense structure at Ga'an Point, one of a

cluster of defense structures on the Agat Beach Unit (CLI

Team/PISO/2001).

| Characteristic Feature |

Type Of Contribution |

LCS Structure Name |

IDLCS Number |

Structure Number |

| Cluster arrangement of Japanese defense cave structures within Apaca Point | Contributing | |||

| Cluster arrangement of Japanese defense cave structures within Asan Point | Contributing | |||

| Cluster arrangement of Japanese defense cave structures within Bangi Point | Contributing | |||

| Cluster arrangement of Japanese defense cave structures within Ga'an Point | Contributing | |||

| Cluster arrangement of Japanese defense caves structures within Adelup Point | Contributing | |||

| Interpretive displays and signs | Non-Contributing | |||

| Monuments scattered throughout the sites | Non-Contributing | |||

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

wapa/cri/part3a.htm

Last Updated: 03-May-2004